4 The Science of Persuasion: A Little Theory Goes a Long Way

Lynn Meade

Don’t raise your voice, improve your argument.

―

I want to dive into some of the theories and models of persuasion to help you understand how people think. Knowing how to persuade is one thing, knowing the mechanics of persuasion is moving you to the advanced level. This information will guide you to form strong persuasive arguments. Knowledge is power and I am giving you the power to know how to persuade. I want to educate you to utilize the psychology of persuasion but also want to encourage you to do it ethically.

Elaboration Likelihood Model

When I was in graduate school, my computer got attacked with the Michelangelo virus. In short, when I turned on my computer on Michelangelo’s birthday, it wiped out everything on my computer. At least that’s what they told me at the computer repair store. I had spent a month of my life researching and writing my persuasion paper and it was gone in an instant. In a moment of what can best be described as a graduate school freak out, I went to the store to buy a new computer. I looked at the salesperson and said, “Quick, show me which computer to buy.” He pointed at one, I bought it, and went home and started writing.

Was I persuaded to buy a computer by the salesperson? I bought one so clearly, I was persuaded, right? Which persuasion technique did he use? Could this even count as an act of persuasion? Sometimes, we just want to decide without putting too much thought into it. You could argue that I didn’t put any thought into it. I didn’t have time to research; I didn’t have the mental capacity to think about which computer was best for me. I trusted the decision to the person in the computer store–he was the one in the red shirt after all. He worked there so he must know about computers.

The next time I bought a computer, I wasn’t in such a stressful situation. I took my time and shopped around. I talked to multiple salespeople, and I read reviews. I even made a spreadsheet of the features and the prices. I put a lot of thought into picking the right computer. Was I any more or less persuaded to buy? After all, in both cases, I bought a computer.

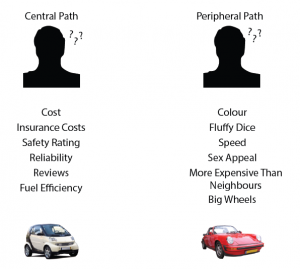

Petty and Cacioppo developed the Elaboration Likelihood Model as a way to explain how persuasion works in different scenarios–particularly, how sometimes we think a lot about our decisions and how sometimes we look for other ways to be persuaded. They said we go on different persuasion routes. When we are thinking (cognitive elaboration) about our decision, they would say, we are taking the central route. We take this thinking route when there is personal involvement and personal relevance. When we are not thinking–because of the situation, our mood, our inability to understand, or the fact that it is not a big decision for us– they would say we are taking the peripheral route. The peripheral route can be thought of as deciding based on anything other than deep thought. In my case, my decision was made based on the authority of the person.

Which of the computers do you think I would likely suggest to a friend–the one bought fast because it was recommended or the one bought after much research? Which computer did I think was the best computer? If you guessed the one that I shopped around for, you would be right. That is the computer I would most likely believe was the best one and that is the one I would most likely recommend to a friend. It makes sense. When we think about our decisions, persuasion is more long-lasting, we are more committed to the decision, and we are more likely to tell others.

What does any of this have to do with you writing a persuasion speech? Knowing that people are persuaded differently can help you design your persuasive arguments. Deciding whether you are going for thoughtful or peripheral persuasion is key.

I used to work for a non-profit and did a lot of fundraising speeches. If I wanted people to be persuaded to give money and have a long-term emotional and financial commitment to the organization, it made sense to persuade them via the central (thinking) route. That meant, I had to tell them what we did and give them facts and details about our organization. I had to build trust and I had to help them believe in the cause.

By contrast, my son was in marching band so there was always a fundraiser where we sold overpriced candy to our friends to support his upcoming trip. The persuasion I used was usually some version of, “My son is selling candy bars for his upcoming band trip, would you help support him.” There was not a lot of thinking when people were buying these candy bars. They were buying because they liked my son, they knew me, or because I bought cookies from their daughter for her fundraiser. This was peripheral persuasion one candy bar at a time.

Elaboration Likelihood Model–What’s the Big Idea?

- If you want your persuasion to be long-lasting, persuade them via the central route. Offer facts, data, and solid information

- If you want a quick persuasion where they don’t put much thought into it or if your audience is not very knowledgeable, tired, or unmotivated, persuade them by the peripheral route.

Judgmental Heuristics

In Elaboration Likelihood Model, we find that people are persuaded in one of two ways– because they are thinking about it–the central route–or they are not thinking about it–peripheral. There is an entire chapter dedicated to how to research which is the central route so for now, I want to talk about the peripheral route.

Researcher and business speaker, Robert Cialdini, has spent a lot of time researching peripheral routes to persuasion. He suggests that we often take shortcuts in decision-making, he calls it judgmental heuristics. Heuristics is just a fancy way of saying shortcut. We often take shortcuts in making our judgments. For example, we might believe that expensive products are better products and use that to decide which item to buy. Cialdini has identified several different shortcuts that people use when making decisions.

- Authority

- Liking

- Commitment and Consistency

- Social Proof

- Scarcity

- Reciprocation

- Unity

Authority

When my doctor prescribes a medicine, I don’t ask if it’s the best, I just take it. He is the authority after all. When a man in a uniform in the computer store tells me which computer to buy, I believe him, he is the pro. It can be helpful to trust those who know more than you on a topic. The power of authority can be very persuasive.

As a speaker, you can capitalize on the persuasive power of authority by telling a story of your encounter with the product–in this case you have the authority of one who knows. I heard many speeches about the benefits of cold showers, but it was not until I had a student who told me his specific story that I was persuaded enough to try it for myself. Another way you can leverage authority is to cite credible people. You can enhance your own ethos by the way you research and handle your sources. Make sure that you use credible sources and make sure that you mention the title of your sources. For example, Say “Dr. Martin, a heart surgeon at the Mayo Clinic.”

Liking

People are persuaded by those they like–that is obvious. What is not so obvious are the ways that liking can be enhanced–similarity, compliments, and concern. People are more likely to like people who dress like them. If you are giving a speech to a group in ties, you should dress formally. If the group is more of a T-shirt and khakis type, you shouldn’t dress as formally. People like people who are similar. By researching your audience well, you can find ways to look for common ground.

Another way to enhance liking is with a sincere compliment. I’m not talking about a cheesy, overly flattering type. I am also not suggesting that you lie. I am saying that you can find something to like about them and let them know. In her TED Talk, Lizzie Valasquez had a very enthusiastic front row and she looked down and said, “You guys are like the best little section right here.” Finally, people like those who are passionately concerned about an issue. As a speaker, don’t aim to be perfect, aim to be passionate.

Commitment Consistency

Commitment/consistency has to do with finding something that people are already demonstrating a commitment to and then encouraging them to act in a consistent manner. If you see someone carrying a water bottle, you can say, “I see you are committed to health. I notice you take that bottle with you to all your classes. I would like you to think about one more thing that can influence your health.” In this example, you find something that a person is committed to and you encourage them to be consistent.

When you research your audience, find things that they care about and touch on those as you encourage them to be consistent. When I spoke to community groups as a fundraiser, I would look up their mission and it often involved something about helping people so I might say, “I see from your mission that you are community-minded. I would like to share with you one more way that you can carry your mission into this community by helping.”

Social Proof

People look to other people to know how to act. Every time, I buy things online, I look to see how others have evaluated the product first. I ask my friends if they have ever tried the product and what they think. I look to others to help me decide.

If you are doing a persuasive speech on a product, you can ethically persuade using social proof by showing how many stars a product has or you could read a poll about how many people support a measure. You can also interview those who are similar to your audience and then report back your findings. Talking about what Instagram and YouTube influencers believe can be powerful if it is someone the audience cares about.

Each of these judgmental heuristics carries with it the danger of abuse, so it is important to be ethical in your use of persuasion. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention to you that when it comes to social proof, it can become a bandwagon fallacy. Take for example fad diets. Just because they are popular, doesn’t mean they are healthy. Just because everyone thinks it is true, that doesn’t mean that it is true. When persuading using social proof, we want to ethically show why others like something and avoid the bandwagon fallacy which assumes that just because a lot of people like something that it must be good.

Scarcity

I am such a sucker for limited-time-only sales. I’m also a victim of buying something because it is the last one. People hate to miss out on things which is why scarcity as a persuasive tool is so powerful. Scarcity can happen because there is not very much of something, (limited numbers) or there is not very long to get it, (limited time) or the information is restricted (limited information). As a speaker, you can encourage your audience to act immediately because the deadline is coming soon or to buy a product because they are likely to sell out.

People hate to have their options limited. “Don’t tell me I can’t have it because then I want it.” Researchers talk about this in terms of psychological reactance. Psychological reactance is a heightened motivational state in reaction to having our freedoms restricted. This, in part, explains why ammunition sales skyrockets under the threat of gun control measures and why teenagers fall even more madly in love when parents forbid them to date. Leveraging psychological reactance ethically can be tricky, but it can de be done. “There are just 20 more days until the election to research your candidate” or “concert tickets usually sell out the first few hours so if you want to go you have to be ready.” These are honest statements that can encourage the audience to act.

Reciprocity

If you do something for me, I feel obligated to do something for you. This is why I always feel obligated to buy a gift for someone who buys me one or to say something nice to someone who compliments me. One of my students persuaded us to try making gifts instead of buying them. She demonstrated an easy-to-make and thoughtful gift and then she gave us a hand out of the steps and supplies. Attached to the handout was a coupon for the local craft store. The act of giving us a handout and the added free coupon enhanced the likelihood that we would comply. In case you are wondering, yes, I was persuaded. Yes, I took the coupon, bought the supplies, and made family and friends etched glasses for Christmas.

Jane McGonigal in her TED Talk, The Game that Can Give You 10 Extra Years of Life, said: So, here’s my special mission for this talk: I’m going to try to increase the life span of every single person in this room by seven and a half minutes. Literally, you will live seven and a half minutes longer than you would have otherwise, just because you watched this talk.” She is promising to give us something in exchange for our time so we feel the pressure to listen.

Unity

People want to feel a sense of unity with a group. This group can be everything from their favorite sports team to whether they or dog or cat lovers. Finding ways to help the audience feel like a special group or like they are part of something, can be important to persuasion. “Join the club,” “be one of us,” “as Razorback’s we all feel…” are examples of how that is used. Another way to activate the principle of unity is to use insider language (if you are part of the group if not, it comes off as sucking up or cheesy).

Cialdini called these seven the “weapons of influence.” To me, the idea of persuasion as a weapon assumes that it is used to attack or to defend. I prefer to use the metaphor of a tool instead of that of a weapon–allow me to illustrate. I am a gardener, so I use the shovel to dig holes to plant flowers–it works as a tool. If I see poison ivy, I might use the shovel to defend myself by removing the poison ivy. If I see a snake, I might hit it with my shovel, and then the shovel becomes a weapon. These persuasion principles can be that way as well. They can be tools or they can be weapons and it is up to the one holding the tool to decide which was to use this information.

Judgmental Heuristics–What’s the Big Idea?

- People take shortcuts when making decisions: authority, liking, commitment and consistency, social proof, scarcity, reciprocation, unity.

- It is important to be ethical when you use shortcuts.

You cannot reason people out of a position

that they did not reason themselves into.

― Bad Science

Social Judgment Theory

I have a colleague that travels around the country speaking on college campuses and at farmer’s markets telling people why they should not eat meat. He finds the eating of meat completely unethical.

I’ve noticed that when it comes to meat-eating, people have strong opinions on either side. Think about it, would you eat a horse? dog? goat? rabbit? Some of you have grown up eating meat all your lives and consider it a tasty and healthy way to eat. For others of you, the very thought of eating any animal product seems cruel. Most reading this will fall somewhere in between. Look at the chart below and decide, which of the category best describes you.

| Eats all meat—horse, goat, dog, lamb, beef, pork, chicken, rabbit, fish | Carnivore Technically Omnivore unless you only eat meat. |

| Eats many types of meat–goat, lamb, beef, pork, chicken, rabbit, fish | |

| Eats many types of meat–deer, beef, pork, chicken, fish | |

| Eats domestic meat— beef, pork, chicken, fish | |

| Eats some meat–chicken, fish | Flexitarian |

| Eats fish, eggs, and dairy | Pescatarian |

| Eats eggs | Ovo-vegetarians |

| Eats no meat or eggs but consume dairy | Lacto-vegetarian |

| Eats no meat or eggs but consume honey | Beegan |

| Eats no animal products at all | Vegan |

As you looked at the list there were some categories you found acceptable, and some you did not. In all honesty, most of you did not think that I was going to suggest eating dogs and horses. When you saw that on the list, most of you didn’t think of those as tasty options. Social Judgement Theory proposed by Sherif, Sherif, and Nebergall suggests that on any topic from diet to abortion and gun control to movie choices, we have an idea of what we like and are willing to accept and what is out of the question. The researchers studied human judgment to understand when persuasive messages are likely to succeed, and it comes down to how we fit into the ranges and how closely that message is to what we already believe. Each of us has a favorite position on any given topic, they call that the anchor position. As you looked on the chart and picked the category that best describes you, you found your anchor position. On the list, you likely found several categories that you would be willing to accept and maybe several categories you reject entirely.

Let’s go back to a colleague of mine, remember, the one who speaks on campuses about veganism. When he looks at this chart, the only position he is willing to accept is to eat no animal products at all. The researchers would say that he is ego-involved because he has a large group of ideas he rejects. How hard would it be to get him to try eating a dog? a goat? an egg? As you can imagine, if I suggest that he tries eating goat, he will think that position is too extreme and that as individuals we are far apart in what we believe. On the other hand, I might be able to nudge him up the continuum a little. Maybe, I could convince him to try honey. After all, no bees were harmed from making honey and it does not contain any meat. People with extreme views can be moved, but only in small increments. If I want the persuasion to work, I might be able to persuade him to try honey.

Now, think of a friend you might know who hunts, and fishes, and eats deer, rabbit, and squirrel. This friend of yours likes trying different types of jerky-like elk and moose. How hard would it be to convince him to try eating a dog? How about a goat? Since your friend has a large range of ideas he already accepts, adding one more animal to the list of things he eats might not be that hard. He would be much more likely to try a dog than would my vegan friend. It doesn’t matter how good we are at persuading as much as how close that persuasion is to what they already believe.

In any audience, you will have people all up and down the spectrum of beliefs. It is your responsibility to try to find out as much as you can about your audience before your speech, so you will know generally where they are. You will have more luck persuading people if you try to move them a little as opposed to move them a lot. Every semester, a vegan group comes to the University of Arkansas campus and passes out flyers promoting a vegan lifestyle. I’ve noticed their messages have slowly changed from meat is murder and you should never eat meat because production is hard on the environment to a more palatable message to try eliminating meat one day a week. Maybe these vegans learned about Social Judgement Theory or maybe they learned by trial and error that moving someone from one extreme to the next is an unlikely feat.

Alexander Edwards Coppock did his dissertation looking at small changes in political opinions, he found the following:

- When confronted with persuasive messages, individuals update their views in the direction of information. This means, if you give them good information, they are likely to be persuaded by it.

- People change their minds about political issues in small increments. Like mentioned before, they are more likely to move in small increments.

- Persuasion in the direction of information occurs regardless of background characteristics, initial beliefs, or ideological position. Translation, good information can be very persuasive regardless of what they believed before.

- These changes in political attitudes, in most cases, lasted at least 10 days. In other words, good facts help people to change their attitudes and that information can stick.

In summary, if you provide people information and attempt to persuade them in small increments regardless of their prior beliefs, they can change their political attitude and that change will stick.

Social Judgement Theory–What’s the Big Idea?

- People have preexisting beliefs on topics. Some people have many variations they are willing to accept, and other people are very set in their ways and will only tolerate a narrow set of beliefs.

- It is nearly impossible to get people to move from one extreme to the next. It is better to get them to move their position a little.

- If you try to move people with narrow views, they will likely reject your ideas and think you are too extreme.

- People who have a wide variance of beliefs are more open-minded to change as long as you don’t try to move them too far from their anchor position.

Michael Austin Believes We Should Encourage Open Discussion

Small acts of persuasion matter, because there is much less distance between people’s beliefs than we often suppose. We easily confuse the distance between people’s political positions with the intensity of their convictions about them. It is entirely possible for people to become sharply divided, even hostile, over relatively minor disagreements. Americans have fought epic political battles over things like baking wedding cakes and kneeling during the national anthem. And we once fought a shooting war over a whiskey tax of ten cents per gallon. The ferocity of these battles has nothing to do with the actual distance between different positions, which, when compared to the entire range of opinions possible in the world, is almost negligible.

None of this means that we can persuade our opponents easily. Persuading people to change their minds is excruciatingly difficult. It doesn’t always work, and it rarely works the way we think it will. But it does work, and the fact that it works makes it possible for us to have a democracy.

― We Must Not Be Enemies: Restoring America’s Civic Tradition

Discuss This

When trying to persuade others. It is helpful to dress similar to the audience and adapt your speech to the audience and context. After all, you would not use a college-level vocabulary when speaking to third graders. When does adaptation, become manipulation? Some people noted that Hillary Clinton changed her accent to adapt to her role and her audience. Watch this video and discuss what you think–Is she adapting appropriately or over adapting in a manipulative manner.

Lawrence Rosenblum, a psychology professor at the University of California, studies speech imitation and he says “When people are imitated, they are more likely to like the person they’re interacting with — they’re more likely to rate the interaction as successful.” As mentioned before, we like people who are like us. Rosenblum also noted that people tend to naturally imitate others’ body language and speech when making a point. Particularly if it is a persuasive point. He would suggest that we don’t even think about it, we just adapt.

So what do you think about Hillary Clinton’s accent change? Would it make you like her more? Did it seem to be a natural adaptation? If you were a political speech coach, what would you suggest that she do?

To be persuasive we must be believable;

to be believable we must be creditable;

to be credible we must be truthful.

―

Ethics in Persuasion

You are given a lot of power when you have the platform and an audience. It is important that you use that power ethically. Researchers Baker and Martinson created the TARES test as a way to examine the ethics of persuasive messages. Read through these questions to see if your persuasive message meets the five principles for ethical persuasion.

TARES Test: Five Principles for Ethical Persuasion

|

|

Truthfulness (of the message)

|

|

|

Authenticity (of the Persuader /Speaker) The Principle of Authenticity “combines a cluster of related issues including integrity and personal virtue in action and motivation; genuineness and sincerity in promoting particular products and services to particular persuadees; loyalty to appropriate persons, causes, duties, and institutions; and moral independence and commitment to principle.” |

|

|

Respect (for the Persuadee) The Principle of Respect requires that professional persuaders “regard other human beings as worthy of dignity, that they do not violate their rights, interests, and well-being for raw self-interest or purely client-serving purposes. It assumes that no professional persuasion effort is justified if it demonstrates disrespect for those to whom it is directed.” |

|

| Equity (of the Persuasive Appeal)

The Principle of Equity “requires that persuaders consider if both the content and the execution of the persuasive appeal are fair and equitable if persuaders have fairly used the power of persuasion in a given situation or if they have persuaded or manipulated unjustly.” |

|

|

Social Responsibility (for the Common Good) The Principle of Social Responsibility ” focuses on the need for professional persuaders to be sensitive to and concerned about the wider public interest or the common good. It represents an appeal to responsibility, to the community over [raw] self-interest, profit, or careerism” |

|

| ** The TARES test was originally developed to test advertising and public relations campaigns. It was applied here to persuasive speeches. For relevance and ease of use, the list of questions on the test was paired down. The original paper and full list of questions can be accessed here: http://www.communicationcache.com/uploads/1/0/8/8/10887248/the_tares_test-_five_principles_for_ethical_persuasion.pdf |

We’ve talked about three major persuasive theories, Elaboration Likelihood Model, Judgmental Heuristics, and Social Judgement Theory. Each one offers insight into how people are persuaded. Woven in all of these is a thread of ethics. Thinking about persuasion as you build your speech and building your points based on proven models will help you to take your persuasive speaking to the next level.

Key Takeaways

Remember This!

- The Elaboration Likelihood Model assumes that people are persuaded via a thinking (central) or nonthinking (peripheral) route.

- Judgmental Heuristics is using shortcuts to decide. These shortcuts are authority, commitment/consistency, unity, reciprocity, liking, scarcity, social proof.

- Social Judgment Theory suggests that people are best persuaded when a message is not too far from what they already believe, and it is better to persuade people in small increments.

- The TARES test examines the ethics of a persuasive message: Truthfulness, authenticity, respect, equity, social responsibility.

References

Austin, M. (2019). We must not be enemies: Restoring America’s civic tradition. Rowman & Littlefield.

Baker, S. & Martinson, D.L. (2001). The Tares Test: Five principles for ethical persuasion. Journal of Mass Media Ethics. 16 (2&3). 148-175. http://www.communicationcache.com/uploads/1/0/8/8/10887248/the_tares_test-_five_principles_for_ethical_persuasion.pdf

Bloomberg Quicktake (2015). Hillary Clinton’s accent evolution (1983-2015). [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UCyvyyo6dtQ Standard YouTube License.

Brehm J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press.

Brehm J. W. & Brehm S. S. (1981). Psychological reactance – a theory of freedom and control. Academic Press.

Cialdini, R.B. (2016). Pre-suasion: A revolutionary way to influence and persuade. Simon and Schuster.

Cialdini, R.B. (2009). Influence science and practice. Pearson.

Coppock, A. E. (2016). Positive, small, homogeneous, and durable: Political persuasion in response to information. [Doctoral Dissertation, Columbian University]. Proquest https://doi.org/10.7916/D8J966CS Available https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8J966CS

Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203–210.

Gass, R.H. & Seiter, J.S. (2014). Persuasion, social influence, and compliance gaining. Pearson

Goldwater, B. Bad science quote. Goodreads.

Hogan, K. (1996). The psychology of persuasion: how to persuade others to your way of thinking. Pelican.

Hovland, C.I. & Sherif, M. (1980). Social judgment: Assimilation and contrast effects in communication and attitude change. Greenwood.

McGonigal, J. (2010). Gaming can make a better world TED Talk.[Video] YouTube. https://www.ted.com/talks/jane_mcgonigal_gaming_can_make_a_better_world?language=en Standard YouTube License.

Murrow, E. R. Quote. Goodreads.

O’Keefe, D. (2008). The international encyclopedia of communication. John Wiley and Sons.

Petty, R.E. & Cacioppo, J.T. (1984). Source factors and the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 668–672.

Petty, R.E. and Cacioppo, J.T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. Springer-Verlag.

Sherif, C. W. & Sherif, M. (1976). Attitude as the individuals’ own categories: The social judgment-involvement approach to attitude and attitude change. Attitude, ego-involvement, and change. Greenwood Press.

Steindl, C., Jonas, E., Sittenthaler, S., Traut-Mattausch, E., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Understanding Psychological Reactance: New Developments and Findings. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie, 223(4), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000222

Address at the Nelson Mandela Foundation in Houghton, Johannesburg, South Africa. Goodreads.

Tyson, J. (2021). Picture: eat what makes you happy. https://unsplash.com/photos/ZA9PHAnVP5g

Valasquez, L. (2013). How do you define yourself? TED Talk. [Video] YouTube. https://www.ted.com/talks/lizzie_velasquez_how_do_you_define_yourself?language=en Standard YouTube License.

Media Attributions

- Man in front of group © Campaign Creators is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- ELM © Joe1992 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- jon-tyson-ZA9PHAnVP5g-unsplash © John Tyson is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license