6 Engage Your Audience: Don’t Spit Random Words at Generic People

Lynn Meade

The success of your presentation

will be judged not by the knowledge you send

but by what the listener receives.

Lilly Walters, Secrets of Successful Speakers

There are five words that can change everything about how you look at public speaking. These four words can alter how you look at nervousness, how you design your content, the way you present, and the way the audience receives the message. What are these words? “It is not about you.”

It is Not About You

It is not about you. So, there you have it–the secret to success in speaking wrapped up in five little words. It is not about you; it is about your audience. Most of the time, speakers think, “I have this great message I need to tell people” or “I need to inform them of what I know.” In each case, it is about “I”. To be a successful speaker, you have to change your way of thinking. A speech is not about you, the speaker, it is about them, the audience. It is about the fact they need something, and you can provide it for them. They may need information, they may need to be inspired, they may need to know about a product that will improve their lives, they may need to celebrate a special moment. They have needs and when your message meets those needs, your audience will be transformed. Chris Anderson of TED talks says, The truth about “speaking your truth” is this: “If the audience doesn’t understand how your truth applies to them, or what they get by learning about your dreams, they’ll tune out or quickly forget what you’ve said.” The more you think about your audience and explore who they are and what they need, the more you can tailor your speech.

Treat your audience as guests

who’ve consented to give you

some of their precious time and attention.

Don’t abuse their gift

by making them feel like captives

who are compelled to listen to you.

Vivian Buchan, Make Presentations with Confidence

Give Your Audience Something of Value: Audience Before Content

A speech is a gift you give the audience. Chris Anderson, the curator of TED Talks, says, “Focusing on what you should give, should be the foundation of your talk.” From the moment, you are tasked with giving a speech, you should ask yourself what gift you have to give. One way to think about it is the acronym ABC-audience before content. One professional speaker helps herself to think about what she gives by imagining herself handing out one-hundred-dollar bills to each audience member. This helps her remember her speech should give each person something of value.

Game designer Jane McGonigal tells her audience she is giving them something valuable. She suggests she will give them seven and a half extra minutes to their life. Watch her introduction to hear for yourself.

I’m a gamer, so I like to have goals. I like special missions and secret objectives. So here’s my special mission for this talk: I’m going to try to increase the life span of every single person in this room by seven and a half minutes. Literally, you will live seven and a half minutes longer than you would have otherwise, just because you watched this talk.

Speech is about serving your audience instead of serving your agenda. One group of speech coaches, Ginger Public Speaking, emphasize being servant speakers. They illustrate the difference between taking and serving this way:

Normal public speaking can focus more on taking from an audience:

- I need them to listen to me.

- I need them to look interested in what I’m saying.

- I need them to laugh at my jokes.

- I need them to affirm my expertise.

- I need them to know how good I am.

Servant speaking is all about building a community:

-

- I want to give my community what they most need to hear.

- I believe my message will bring benefit to those listening.

- I want the people listening to me to feel a part OF something not apart FROM something.

Did you notice three out of four of the key features that Chris Anderson mentions have to do with the audience?

1. Limit your talk to just one major idea.

2. Give them a reason to care.

3. Build your ideas based on what the audience already knows.

4. Make your idea worth sharing. Who does this idea benefit?

The information in this video is for a specific context–how to give a TED Talk–but many of the lessons apply to public speaking in general.

Getting into the Mind of Your Audience

“Speakers do not give speeches to audiences; they jointly create meaning with audiences,” according to scholars Sprague, Stuart, and Bodary, to create meaning, you need to think about what your audience already knows. You need to get into the mind of your audience. The key to good speaking is to put an idea in the mind of your audience. For this to work, you need to think about them and their worldview. To do this, you need to research your audience as well as your topic.

Frank Luntz knows all about how to get in the mind of an audience, it’s what he does for a living. He is an American political and communications consultant and he polls audiences to find out their beliefs. He specializes in helping speakers find what words best resonate with audiences. He says:

You can have the best message in the world, but the person on the receiving end will always understand it through the prism of his or her own emotions, preconceptions, prejudices, and preexisting beliefs. It’s not enough to be correct or reasonable or even brilliant. The key to successful communication is to take the imaginative leap of stuffing yourself into your listener’s shoes to know what they are thinking and feeling in the deepest recesses of their mind and heart. How that person perceives what you say is even more real, at least in a practical sense, than how you perceive yourself.

This means not just looking at an audience in terms of demographics, but rather, what are their goals, why should they care, what do they need?

Ask Yourself, What Do They Need?

Many of you are reading this book because you are in a public speaking class. If so, you are thinking, “What do I have to do to make an “A” on this speech?” or “What is the least I can do to get my college credit?” Notice that both approaches focus on “I.” Realize when you give your presentation, there will be an audience of college students that need something. What do they need? They need not be bored. They need to think it was worth it to come to class. They need to learn things. They need to be inspired. If it is a persuasion speech, don’t think about what you need to persuade them to do, think about them and how their lives will be improved if they listen to your speech and act on the important issue you presented. If you are giving a ceremonial speech, think about how you can make them feel a part of something–make them feel included.

The goal of effective communication

should be for listeners to say

‘Me too!’ versus ‘So what?’

– Jim Rohn, motivational speaker

I want to share with you a few scenarios from my own experience. Read carefully and consider what the audience needs.

INFORMATION:

I spoke to the monthly meeting of Kiwanis about a nonprofit I managed.

What did my audience need?

- To enjoy themselves among friends after the meal.

- To know about what is happening in their community.

- To feel like their involvement in the club was meaningful.

- To feel like they could do things that will make a difference.

- To feel like they are a part of something important.

Why did they come to the speech?

Because they are part of a club that has weekly luncheons with community speakers. They are there to be with like-minded individuals, they are there to find ways to get involved, and they are there to network.

CELEBRATION:

I spoke to a sorority at their annual banquet that honored the academic achievements of the group.

What did my audience need?

- To feel bonded with others in their sorority.

- To feel proud of their achievements.

- To feel motivated to succeed and make good grades in college.

- To feel like the university cares about their success and recognizes their hard work.

Why did they come to the speech?

They liked being part of a group where they make friends and celebrate accomplishments. They were required to attend, or they would be fined. They knew me or one of the other speakers that day.

PERSUASION:

I spoke to a major corporation about why they needed to buy diesel engine parts from the company I worked with.

What did my audience need?

- To know about the product and how it might benefit them.

- To be able to understand the details of the product enough to make an informed decision.

- To feel empowered to make an informed choice.

- To feel good about their decision.

- To be able to get back to work in a timely fashion.

- To feel like they were doing what was right for their company and their customers.

Why did they come to the speech?

They benefited from finding good products for their company. It was their job. Saving their company money while buying a good product makes them look good.

TRAINING:

I spoke at a teaching camp to a group of college faculty and gave them tips for teaching.

What did my audience need?

- To know about specific ways to improve teaching.

- To feel good about being a teacher.

- To understand the teaching tip in a way they could apply it.

- To connect with and feel encouraged by other teachers.

Why did they come to camp?

It is an optional camp, so they came specifically to learn to be a better teacher. They came to spend time with friends.

Do this anytime you have a speech to give. Put yourself in the mind of the audience and write their needs and motivations.

Write down what they need and why they are at the event. It is easy to think about the tangible reasons they attended, but it is helpful to think about the emotional reasons they are there. Are they there to bond with friends? Are they there to be inspired? Are they there because they have to be? What reward do they get for coming? Notice in some of my examples, I have things like “to feel good,” “to know more,” “to connect.”

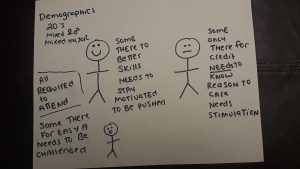

Make yourself a graphic of the target audience members. As you write your speech, keep looking at this reference so you keep the audience’s needs in mind. Here is one I made for students I have in my public speaking class.

Nancy Duarte, the author of The Art and Science of Creating Great Presentations, suggests you ask yourself these questions about your audience.

- Lifestyle: What does a walk in their shoes look like?

- Knowledge: What do they already know and not know about your topic?

- Motivation and Desire: What are their wants and desires? What motivates them?

- Values: What is important to them? How does their use of time and money reveal their priorities?

- Influence: What influences their behaviors and thoughts?

- Respect: What makes them feel respected? How do they give and receive respect?

Consider the Situational Needs

Consider the setting of your speech. After a big lunch, people may be tired. If they have listened to other speeches before yours, they may be fatigued from sitting and listening so long. If they have been listening for a while, consider having them engage briefly with another audience member. If you know they have been sitting, consider how you can have them move a little. If the room is stuffy, or loud, or if they were forced to come and listen, acknowledge how much you appreciate their presence.

Consider the Audience’s Needs

People don’t remember what we think is important.

They remember what they think is important.

John Maxwell, leadership expert

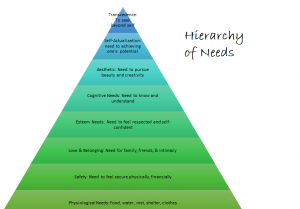

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is one tool you can use to help you analyze audience needs. Work through the pyramid and see if you can relate each level to your topic in some way. I find it is particularly helpful to use it as a brainstorming tool when constructing speeches. In short, psychologist Abraham Maslow suggested people are motivated by their needs and they seek to satisfy their needs. For our purposes, we won’t delve into the larger theory but rather acknowledge that people seek to satisfy their needs. The more you identify and talk to their need and demonstrate how those needs can be satisfied, the more likely they are to have a positive response to your topic (and more likely to be persuaded).

Let’s work through an example of this. Imagine you are doing a speech to persuade people to take a self-defense course at a local gym.

- PHYSIOLOGICAL NEEDS: People need to sleep: I can remind listeners that they sleep better once they exercise. They will sleep better knowing they can protect themselves. Taking a self-defense class will help them get a good night’s sleep.

- SAFETY NEEDS: People need to feel safe: I can remind them of crime statistics to make them feel unsafe so they take the class to regain a sense of safety.

- BELONGING NEEDS: People need to belong: I can encourage them to take the class with a group of friends or I can remind them of times they missed spending time with friends because they were uncomfortable being out late at night alone. Take a self-defense class will give them the confidence they need to go out with friends.

- ESTEEM NEEDS: People need to feel good about themselves: I can remind them how bad it feels to not be able to fend for themselves and tell them how good it feels to have the confidence to know how to defend themselves. Learning new skills makes you feel good. Independence feels good.

- COGNITIVE NEEDS: People have the need to know, so I can tell them about the science of some of the techniques and why they work.

- SELF-ACTUALIZATION NEEDS: People need to feel safe, they need to know and belong, so they can work to fulfill their life’s goals. A college student who is afraid to walk to their night class, might skip class and then fall short of their personal goal of graduating.

Designing a presentation without an audience in mind

is like writing a love letter and addressing it:

To Whom It May Concern.

– Ken Haemer, Presentation Design Manager

Recipe for Listenability

Listenability: What does that mean in plain English?

By using easily understood phrases and words and giving the audience a reason to listen you are making your speech listenable.

Think of your speech in terms of listenability. Communication scholar D.L. Rubin says, “Listenable discourse is characterized by linguistic and rhetorical structures that ease the particular cognitive burdens listeners face.” (What do you think about that quote, appropriate to the audience of this book or unnecessarily wordy and full of big words? Was it a listenable quote–I don’t think so.)

In plain English, make your speech easy to listen to. How do you do that? Glad you asked, let me share with you a few ways.

To Be Listenable

Find Common Ground

Seek to establish a connection with your audience right away. Find common ground or draw from common experiences. If you are talking to a civic organization read their mission statement and seek commonalities. Work in the common ground such as, “Like you, I am passionate about finding a better solution for the homeless in our area.” Recognize similarities if they represent a cause that matters to you, if you have a hometown team in common, if you all ate a catered lunch, or if you all walked uphill to get to class. It is no coincidence when speakers come onto a college campus, they almost always mention one of these: The mascot, the sports team, a place on campus, a famous eating establishment, or a campus hero. These details draw the audience in to listen. People appreciate a speaker who took the time to think about them it will increase both liking and credibility.

When I teach a public speaking class, I always dedicate a day to helping my students understand the audience and how to relate. I ask questions and we put the answers on the board. For example, I ask, “How many like camping?” “How many like cats?” “How many are politically involved?” We put the answers to the questions on the board for everyone to see. Once the board is covered, I explain they should take a picture of this and reference it in all of their speeches. For example, they might say, “I noticed only 20% of the class is politically involved, which is why I decided to persuade you to take a political science class during your time at college” or they might say, “Most of the class said they liked camping. Now I know you like camping, I want to tell you about why you need to go camping along the Buffalo River.”

Sometimes a speaker will use the same speech with different audiences and common ground has to change. Julie Miyeon Sohn, Toastmaster’s competitor, reflected on what she learned about adapting to an audience. Her failure to adapt caused her not to win at the World Championship of Public Speaking:

“One thing I would do differently is changing how I select my speech topic. My story about learning English was well received in Korea because the Korean audience had all had a similar experience to mine. However, I failed to connect with the audience at the semi-final because the story was not very relatable to the international audience. I would change my story to something more universal so that everyone can relate to it regardless of their race, nationality, and age.”

In order to find common ground, you need to take time to get to know the audience. In addition to the traditional research, one speaker suggests reading up on the news before you speak and draw references to things most people might know. Make sure the examples you give are now by most audience members. Speaker Nancy Duarte shares her common ground mishaps:

I referred to an airline, (an example of amazing customer service, Open Skies) to an audience of American business executives, forgetting that an airline with only one route (NY-Paris) wasn’t something many of them would know.

Even if most of your audience knows about your common ground reference, they may have differing opinions about it. Nancy Duarte says,

I learned this the hard way with the same audience, telling them, proudly, how a former customer had asked me for referral to a therapist (everyone goes to therapists in NY!), which provoked guffaws from brawny macho Midwesterners.

Finding common ground with your audience, not only gets their attention, but it helps them get on the same wavelength–literally. Princeton neuroscientist Uri Hasson says the more commonality between a storyteller and listener, the more brain imaging shows that the brains sync up. Let that sink in. When you find common ground through story, it shows up on a brain scan. Your audience’s brain scan lights up in the same places yours does–that is incredible. Thinking about your audience and then finding common ground is crucial to your success.

The royal road to a man’s heart

is to talk to him about the things he treasures most.

Dale Carnegie, Author, Speaker

To Be Listenable,

Reference Someone in the Group

When possible, go to a speaking event early and talk to several people. Engage them in friendly conversation and then ask them questions related to your topic. During your presentation, point them out and say, “Derek was telling me that….” The audience’s attention zooms in when you acknowledge someone from the group. If you don’t have time to visit beforehand, you can always reference the host who invited you. Mentioning anyone they know can draw the audience’s attention.

To Be Listenable,

Tell Them How It Applies to Them

To keep the audience’s attention, talk about what they care about the most–themselves. Get the audience on your side by telling them why this speech is relevant to them. Don’t just assume they know, help them make those connections. Typically, highly engaged, and knowledgeable audiences, need only a light reminder of the topic’s application. For those that are not very knowledgeable or not motivated listeners, you need to tell them specifically how it applies and why. One easy way to do this is to say, “So what, who cares…” Another way is to simply ask the audience, “Why do you think this should matter to you?” Then, answer the question.

To Be Listenable

Use the Language of Your Audience

Author, William Butler Yeats said, “Think like a wise man but communicate in the language of the people.” Make sure that the words you use match the vocabulary and the knowledge level of the audience. Throughout your speech, define your terms clearly and carefully. Be careful not to use jargon or “insider” language that will exclude listeners who aren’t “in the know.” While working for a nonprofit, I was invited to come onto the university campus to speak to campus groups interested in volunteering. To identify with the audience, I told them I was a COMM major. After my presentation, someone came up to me and said, “Ms. Meade, what is a COMM?” I explained it was shorthand for Communication Major. We laughed at my mistake, I apologized for assuming everyone knew what it meant, and then he offered to join my organization. It goes to show you, even within the group (in my case people on a college campus), you can’t assume people know the specialty language. It also goes to show you that you can mess up and still make a friend (if you acknowledge your mistake gracefully).

I am often to be a judge for a unique speech competition. Graduate students have three minutes to explain their research in a way anyone can understand. They have to make it plain enough a layperson can understand what they are doing and what the results mean. Many graduate students have been working in complex theories and specialty language for so long they have a hard time realizing not everyone knows what these concepts mean. It is important you learn to know how to adapt your message to audiences with differing levels of knowledge and complexity.

Watch this Wired video where an astrophysicist explains gravity in five levels of difficulty. (You don’t have to watch the whole video, just watch a little bit of how she talks to each person to get the point). This is an excellent example of talking about the same topic to different audience members.

Finding the right vocabulary and the right tone for the right audience takes a lot of thought and practice. Alan Alda and the Center for Communicating Science issued a “flame challenge” and they asked scientists to explain a flame to 11-year-olds.

To watch more on this https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hS6rOCdy-uo

Here is perhaps the simplest case

of persuasion.

You persuade a person only

insofar as you can talk their language

by speech, gesture, tonality, order,

image, attitude, idea,

identifying your ways with theirs.

Kenneth Burke, American literary theorist

To Be Listenable

Use Inclusive Language

Inclusive language means many things. It means speaking to the knowledge level and education level of your audience. It also means designing sentences where you invite them to be a part.

NO: I know most people worry about what goes into their food.

YES: I know most of us worry about what goes into our food.

The use of “us” and “our,” makes the sentence more personal and friendly. As much as possible, use personal pronouns with your audience. As Shel Leanne points out in the book, Say It Like Obama: The Power of Speaking with Purpose and Vision, these words help to “send the message that the speaker and those listening are on the same team, in the same boat, facing the same fate.”

To Be Listenable

Give the Audience a Map of the Journey so they Won’t Get Lost

Tell them what you are going to say, say it, and then tell them what you said. Along the way, help them stay on track by telling them where they are headed. “Now that we talked about this history of this, I want to share with you the future of the product.”

Always keep the focus on what is the point of your speech. Nancy Duarte, presentation expert suggests, “Every bit of content you share should propel the audience towards that destination.”

To Be Listenable

Take the Audience’s Perspective

Your speech is a journey, and you are taking your audience on that journey with you. Chris Anderson, TED Talk curator says, “It is your job to know about your fellow travelers. What do they need from the journey and how can you help them, so they enjoy the trip and they don’t get lost?” Delve into the audience’s mind, what is their perspective of your topic?

Consider This

When the country music singer, Garth Brooks arrives as the venue, he sits in many of the seats that are pointing at the stage and asks, “What am I doing for this person.” As a speaker, it is good to sit in the many (symbolic) seats of your audience and ask, “What am I doing for this person?”

To Be Listenable

Ask for Audience Participation

Actively involving your audience helps them stay alert and attentive. All too often, speakers seem to spit random words at generic people. The audience is supposed to passively sit back and take in whatever comes their way. An audience is made up of people who need to be considered, addressed, and engaged and it is your challenge to figure out how to connect. Consider using one of the following when engaging your audience:

- Ask rhetorical questions.

- Take an informal poll.

- Ask for a volunteer.

- Have them write something down.

- Ask them to talk with their neighbor about a topic.

- Have everyone yell the answer at the same time.

- Tell them there will be a “test” at the end.

Watch Toastmaster’s World Championship Speech by Darren Tay Wen Jie to see how he relates to the audience.

Look at All the Ways He Connected with the Audience

Darren Tay said in a Business Insider interview that he emphasized the importance of making audience members feel like he was talking directly to them. One way he does this is by asking rhetorical questions of the audience: “If you are all wondering whether the underwear Greg used was clean, I had the same question.” Look at this list of all the ways he connects with the audience in this speech.

- He opens by staring at them directly.

- If you are all wondering whether the underwear Greg used was clean, I had the same question.

- Mr. contest chair, fellow toastmasters, and anyone including those watching worldwide. If you are looking at Calvin Klein here, stop staring! My eyes are up here.

- “I gonna knock you in my teeth and punch you in the guts and laugh at your sorry behind. He didn’t quite use the word- behind. I just cleaned up the words because this is a toastmaster program.

- And, have you ever wondered why a bully needs to tell you the exact sequence that they gonna bully you?

- My friends, whenever I heard those words, my hands would tremble. Have you ever felt so fearful, that you cannot eat or sleep?

- My friends, as much as we tried to deny it, we are our toughest and strongest bully. We beat ourselves up and put ourselves down. Have you ever felt that you are not good enough? I thought that way.

- I’m standing on stage now in front of two thousand of you and more are watching worldwide but I am not afraid anymore. I am in control because I am acknowledging it, I am stepping out of it, observing it, and watching it weaken and fade. My friends, let’s all not run away from our inner bullies anymore. Let us all face our inner bullies and acknowledge its presence and fight. Let us all be together as a family supporting one another because we can all outsmart and (outlast).

Asses and Elephants

Making Assumptions Makes an Ass out of U and Me (ASSuME)

Make a list of the known demographics of your audience and create a profile. Make a list of what you know about them and what you assume about them. Be honest, but don’t let that profile lead you astray. Don’t create unrealistic stereotypes and expectations based on the way you profiled them. For example, just because your audience is made up of seventy-year-old women, does not mean that they have the same values as your conservative grandma. Most of us naturally default to grouping things based on what we already know–don’t assume.

While persuading the class to skydive, one student said, “I know you may not be interested Dr. Meade, but you can tell your sons about it.” Just for the record, I went skydiving the next year– my sons still haven’t been. In another speech, I had a student say, “Now that I have shown you how to make taco casserole, you can take this recipe home with you to make it. Guys, you can take it to your girlfriend.” The guys were upset because she didn’t think they were interested or capable.

In the first example, they made assumptions about abilities and interests based on age, and in the other example, they made assumptions based on gender roles. Don’t assume.

Let’s Talk About the Elephant in the Room

What do you call people? Frankly, this is a tricky topic. It is like the elephant in the room that everyone can see but no one wants to mention. African American/Black/Native American/Indian/Transexual/Non-binary–there are so many different words in the “people dictionary”. What is acceptable and what is offensive seems to change regularly. If I am honest (and I try to be), I get nervous about what to call people, because I’m afraid I will mess up and someone will get upset when I didn’t mean any ill intent. Then I think, why do people get their feeling hurt over the littlest things? Well, if you are on the receiving end, they are not little things. I try to remember when someone said hurtful things to me and then it is easier to remember why it matters. Even if the person who hurt my feelings wasn’t trying to be mean, it still hurt. When I was hurt by those words, I was too busy with my own thoughts to hear anything else they had to say.

Hurt people do not listen. If the point of my speech is to be heard and I said something that causes my audience not to listen, I hurt not only them but my own cause.

I once spoke before an interfaith board of directors. I had a list of the names and organizations that were represented, and I thought I had done all my research. During my presentation, I talked about the need for volunteers in the community, I talked about how each of their groups represented a belief that people should help each other, and then I asked them to “Go back to your churches and ask if they will allow me to come out and give a talk about how your church can get involved with helping others.” After my presentation, a member of the board came up to me and said, “Lynn, not all of us go to church, some of us go to synagogue.” I thanked her for correcting me and I learned to use the phrase “faith groups” instead of the word “churches” when talking to an interfaith audience. Because I was gracious in accepting my mistake, we developed a great working relationship for years to come. Before speaking to a group– do your research. If you mess up (and if you are human, you will mess up eventually), be gracious to those who pointed out your mistake, learn from your mistake, and accept responsibility.

Do no harm. Create no barrier. When taking the audience-centered approach, consider what the audience needs so they can listen. Do your research to learn the preferred name for a group and the vocabulary of the group because it respects the audience. Audience members who feel respected are more likely to listen.

Elephant in the room is an idiom that means to point out an obvious truth or fact.

I didn’t ASSuME that you knew what that phrase means, I gave you a definition.

Your Credibility is Linked to the Audience’s Opinion of You

Every time you speak, you are building credibility, maintaining credibility, or diminishing credibility, according to Ryan Sheets, Director of the Business Communication Lab at the University of Arkansas, your credibility (ethos) is linked to what the audience thinks of you. An audience expects you to not only have knowledge but also to be trustworthy and sincere. What they think about you translates to how much they will listen to your message. That opinion is formed by looking at the way you are dressed, how you carry yourself, the words you say, and the way you address them.

Your credibility is tied up in their opinion of you and whether they think you care about them.

Thinking About the Audience Makes You Less Anxious

When you realize speech is not about you having something to say but rather, you are giving the audience something of value, it changes things. Not only will you give a better speech, but you will benefit yourself as well. When you think about the needs of the audience, you become less nervous. Focusing on their needs and the topic helps you focus on providing a service rather than delivering a performance.

- Instead of thinking, “I am so nervous,”

try thinking “the audience really will benefit from knowing this.”- Instead of thinking, “I will persuade them to do this”

change your thinking to “their life will be better if they try this.”

If you pick a topic you are passionate about and if you believe in it, you will begin to care more about the importance of the topic and less about your own personal discomfort. If you feel a little nervous, think about how your information can improve lives or change people’s perspectives. Make your topic so important that you forget to be nervous.

Quit being so self-centered. It’s not about you—- it’s about the audience. They need something and you have it. Writer Ambrose Redmoon said, “Courage is not the absence of fear, but rather the judgment that something else is more important than fear.”

Don’t be selfish. It does little good to have all that experience and all that knowledge and keep it to yourself. Author Marianne Williamson says, “Your playing small does not serve the world.” It is worth a little discomfort for the awesome privilege you have to change, educate, motivate, and persuade your audience. They need this information, and you are the one lucky enough to get to give it to them. When you spend all your time thinking about how to connect with the audience and how to help them understand what you have to offer, you have less energy to spend worrying about if you are nervous.

I tell myself that what I have to say in any speech

is important for people to hear,

and that I prepped for it,

and am well versed in it.

So basically knowing that what I have to say is worth hearing

makes me confident in saying it.

Andrew Powell, Former University of Arkansas Communication Student

Audience Analysis Tools

There are many ways to gather information about the audience,

Here are a few of the most common and a list of the pros and cons of each

|

Interview

|

|

Pros

|

Cons

|

Survey

|

|

Pros

|

Cons

|

Internet Research

|

|

Pros

|

Cons

|

|

Demographic Data

Demographic data can come from statistical sources or it can come from asking questions to the person who invited you to the venue.

|

|

Pros

|

Cons

|

When we think a speech is about what we have to say, we get it wrong. The whole reason you are giving the presentation is for the audience. The speech is about them, and your job is to figure out who they are and what they need before you write even the first word.

Key Takeaways

Remember This!

- The most important thing to remember is it is not about you; it is about the audience.

- Focus on making your speech listenable.

- Make a list of what your audience needs and the reasons they are listening to your speech.

- Don’t stereotype or make assumptions about your audience.

- Know the right words to use for your specific audience.

- Use a variety of tools to gather information about your audience.

Extras to Help You with Understanding Audience

Exercises

Actor and writer Alan Alda trains communicators by teaching them basic improvisational techniques. The goal is to help them to gain empathy and to learn to read people better. In this video, he explains a couple of ways to gain empathy with your audience.

From the book, If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face by Alan Alda

Please share your feedback, suggestions, corrections, and ideas.

I want to hear from you.

Do you have an activity to include?

Did you notice a typo that I should correct?

Are you planning to use this as a resource and do you want me to know about it?

Do you want to tell me something that really helped you?

References

Alda, A. (2012). Alan Alda’s ‘Flame Challenge’ illuminates the importance of communicating science. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hS6rOCdy-uo Standard Youtube License

Alda, A. (2017). If I understood you, would I have this look on my face? Random House.

Alan A. (2017). Grow your empathy through visual perception. Big Think. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qulq_n5zbTs Standard YouTube License

Anderson, C. (2016). TEDs secret to great public speaking by Chris Anderson. [Video] YouTube. https://www.ted.com/talks/chris_anderson_ted_s_secret_to_great_public_speaking?language=en Standard YouTube License

Anderson, C. (2016). TEDtalks: The official TED guide to public speaking. Mariner Books.

Aristotle. (2007). On rhetoric: A theory of civil discourse, 2nd ed. trans George Kennedy. Oxford University Press.

Broadside Blog. (2012). How to give a speech (Hint: be authentic). https://broadsideblog.wordpress.com/2012/11/15/how-to-give-a-great-speech-hint-be-authentic/

Buchan, V. (2019). Make presentations with confidence. Barron’s: A business success guide. Barron’s Educational Series.

Burke, K. (1969). A rhetoric of motives. University of California Press.

*In the Burke quote, I changed it from “his” to gender-inclusive language “theirs.” A topic worth thinking about and discussing.

Cartier, F.A. (1952). The social context of listenability research. Journal of Communication, 2, 44-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1952.tb00177.x

Duarte, N. (2010). Resonate Present visual stories that transform audiences. Wiley.

Feloni, R. (2016). Here’s a breakdown of the speech that won the 2016 World Championship of Public Speaking. https://www.businessinsider.com/toastmasters-public-speaking-champion-darren-tay-2016-8

Goble, F. (1970). The third force: The psychology of Abraham Maslow. Maurice Bassett Publishing.

Goldberg, B. (2020). Top 5 TED Talk cliches you should avoid. https://masterclass.ted.com/blog/5-TED-Talk-cliches-to-avoid

Harris, L. (2017). Stand up speak out: The practice and ethics of public speaking. Creative Commons License. https://open.lib.umn.edu/publicspeaking/

Jeary, T. (1997). Inspire Any Audience. River Oak Publishing

Kardes, F.R., Kim, J. & Lim, J.S. (1994). Moderation effects of prior knowledge on perceived diagnosity of beliefs derived from implicit versus explicit product claims. Journal of Business Research, 29, 219-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(94)90006-X

Kienzle, R. & J. Miyeon, S. (2017). Losing at the World Championship of Public Speaking. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/losing-world-championship-public-speaking-robert-bob-kienzle-kienzle/

Luntz, F. (2007). Words that work: It’s not what you say, it’s what people hear. Hyperion.

Martin, B.A.S., Lang, B. & Wong, S. (2013). Conclusion explicitness in advertising: The moderating role of need for cognition and argumentation quality on persuasion. Journal of Advertising, 32(4), 57-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2003.10639148

Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4), 370-96. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Maxwell, J. (2010). Everyone communicates few connect: What the most effective people do differently. Thomas Nelson.

McGonigal, J. (2012). The game that can give you 10 extra years of life. [Video] YouTube. License.https://www.ted.com/talks/jane_mcgonigal_the_game_that_can_give_you_10_extra_years_of_life/transcript?language=en Standard YouTube License.

Rubin, D.L. (1993). Listenabilty = oral-based discourse+ considerateness. In Wolvin, A.D. & Coakley, C.G. (Eds.) Perspectives on Listening. Ablex.

Rubin, D.L., Hafter, T. & Arata, K. (1999). Reading and listening to oral-based versus literature-based discourse. Communication Education, 49, 121-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520009379200

Sawyer, A.G. & Howard, D.J. (1991). Effects of omitting conclusions in advertisements to involved and uninvolved audiences. Journal of Marketing Research, 28, 467-474. https://doi.org/10.2307/3172786

Saylor Academy (2012). Stand up, speak out: The practice and ethics of publicsSpeaking. Saylor Academy. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/77

Sheets, R. (2020) Walton College of Business Presentation. The University of Arkansas.

Snippe, E. (2016). 101 quotes to inspire speakers. https://speakerhub.com/blog/101-quotes

Spencer, G. (1995). How to Argue and Win Every Time. St. Martin

Sprague, J., Stuart, D., & Bodary, D. (2010). The speaker’s handbook (9th ed.) Wadsworth Cengage.

Strategic Business Insight. US Framework and VALS Types. http://www.strategicbusinessinsights.com/vals/ustypes.shtml

Tay, D. (2016). Outsmart, Outlast. Toastmasters World Championship. [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v26CcifgEq4 Standard YouTube License

Tempesta, L. (2019). You’ll never look at a bra the same way again. TEDxKCWomen. [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GrxJ-9_qXeM Standard YouTube License.

Toastmasters (2013). Keep your audience engaged. [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JHl4yUQMBYA Standard YouTube License.

Toastmasters: Know your audience. [Video] YouTube. https://www.toastmasters.org/Resources/Know-Your-Audience Standard YouTube License. Walters, L. (1993). Secrets of successful speakers: How you can motivate, captivate, and persuade. McGraw Hill.

Wired. (2019). Astrophysicist explains gravity in 5 levels of difficulty. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QcUey-DVYjk

Wolvin, A. (2017). Listenability: A Missing Link in the Basic Communication Course. Listening Education, 13-21. No doi available.

Wrench, J.S., Goding, A. Ifert-Johnson, D., Attias, B.A. Stand up, Speak out. The practice and ethics of public speaking. Flatworld Knowledge. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/77

Media Attributions

- Audience Listening © M-Accelerator on Unsplash is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Audience © Melanie Deziel is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- OIG4 © Generated with AI ∙ January 31, 2024 at 1:03 PM

- Needs © Lynn Meade is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- sander-dalhuisen-nA6Xhnq2Od8-unsplash © Sander Dalhuisesn is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- hierarchy of needs © Lynn Meade is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Audience by Oliver Tacke CC © Oliver Tacke is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Elephant in the room © Bit Boy is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license