10 The Power of Story: The Secret Ingredient to Making Any Speech Memorable

Lynn Meade

Ideas are not really alive

if they are confined to one person’s mind.

Nancy Duarte, Speech coach and author

We love stories because they are engaging, they ignite the imagination, and they have the potential to teach us something. You have likely sat around a campfire or the dinner table telling stories? That is because stories are the primary way we understand the world causing communication scholar Rhetorical scholar Walter Fisher to call us homo narrans–storytelling humans. Not only is storytelling important in conversation, but it is also important to speechmaking. It is no surprise then, that when researchers looked at 500 TED Talks, they found of the TED talks that go viral, 65% included personal stories.

Professional speakers, college students, politicians, business leaders, and teachers are all beginning to understand the benefits of telling stories in speeches. Increasingly, business leaders are encouraged to move away from the old model of sharing the vision and the mission to a new model of telling the story of the business. Academic literature points out that teachers who use stories can help students understand and recall information. For years, politicians have been coached to include a story in their speeches. They do it because it works, and it is bound in science.

In short, people don’t pay attention to boring things. The story is one way to engage and help ideas come alive. Cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham says, “The human mind seems exquisitely tuned to understand and remember stories—so much that psychologists sometimes refer to stories as ‘psychologically privileged,’ meaning that they are treated differently in memory than other types of material.”

The goal of public speaking is to plant an idea into the minds of your listeners and the most effective way to accomplish that is through a story. I want to share with you three major principles about storytelling and give you concrete ways to incorporate them into your own storytelling.

- Stories, when told properly, will ignite both the reason center and the emotion center of your audience’s brains making them not only more effective in the moment but also more memorable in long run.

- Stories activate the little voices in the audience’s heads and help them think creatively about problems. This activation encourages audiences to act on the idea as opposed to just being passive listeners.

- The best way to tell a story is to connect it to a message, offer concrete details, and follow a predetermined plotline.

(Editorial note: One of the advantages of digital textbooks is I can add videos. In my opinion, the best way to learn about how to write a good story is to see numerous examples of good stories in action. I have provided you with numerous videos illustrating how the story is used in business, used in law, used in entertainment, and used in education so that you can see the many applications. This chapter is different from standard textbooks on the subject because it includes more examples than text. You will only get deep learning if you take the time to watch the video clips.)

Tell me the fact and I’ll learn.

Tell me the truth and I’ll believe.

But tell me a story and it will live in my heart forever.

–Ancient proverb

Stories Engage the Audience and Make a Point

In under four minutes, Mark Bezos, tells a memorable story. He makes us laugh, allows us to see the situation, and then uses all the emotion and visualization he has created to make a powerful point. A good story draws us in and helps us connect with the person and their idea.

The brain doesn’t pay attention to boring things.

– John Medina, author of Brain Rules

Stories Help Ideas Stick

Stories are sticky. A well-told story “sticks” to our brains and attaches to our emotions. A speaker can tell a story in such a way that the audience “sees” the story in their mind’s eye and “feels” the emotions of the story. In some situations, an audience may become so involved in the story they “react” by making facial expressions or gasping in surprise. By “seeing the story” and physically reacting to the story, the audience is moved from a passive listener to an active participant.

Think about college teachers you have had who told stories as part of their lectures. Did it help you to listen? Did it help you to learn? Chances are it did. Researchers Kromka and Goodby put it to the test on one hundred ninety-four undergraduate students. One group listened to a lecture that included a lesson with a story, while others just heard the lesson’s key points. Students that heard the narrative had more sustained attention to the lecture and they did better on a test of short-term recall. The stories helped them remember the material, but there was an added benefit. The students who heard the narrative liked the teacher more and were more likely to take another course from the instructor in the future.

One of the top TED Talks of all time is My Stroke of Insight by Jill Bolte Taylor. In this talk, she weaves a story so engaging that the audience is afraid to blink because they might miss what happens next. Watch as she tells you about the “morning of the stroke.”

On the morning of the stroke, I woke up to a pounding pain behind my left eye. And it was the kind of caustic pain that you get when you bite into ice cream. And it just gripped me — and then it released me. And then it just gripped me — and then it released me. And it was very unusual for me to ever experience any kind of pain, so I thought, “OK, I’ll just start my normal routine.”

So I got up and I jumped onto my cardio glider, which is a full-body, full-exercise machine. And I’m jamming away on this thing, and I’m realizing that my hands look like primitive claws grasping onto the bar. And I thought, “That’s very peculiar.” And I looked down at my body and I thought, “Whoa, I’m a weird-looking thing.” And it was as though my consciousness had shifted away from my normal perception of reality, where I’m the person on the machine having the experience, to some esoteric space where I’m witnessing myself having this experience.

Jill Bolte Taylor

Try This

I’d like to illustrate to you the connection between thinking and doing.

-

- Imagine you are looking at the Eiffel tower.

- Think of two words that start with “b.”

- Think of two words that start with “p.”

- Imagine that I am cutting a lemon in half and then squeezing the juice in a glass.

- Imagine fingernails running down a chalkboard.

When imagining the Eiffel tower, most people’s eyes scan up.

When thinking of the words that begin with “b” and “p”, most people will mouth the words.

When imagining the lemon, many people will salivate.

When imagining fingernails on a chalkboard, many people will tighten their facial muscles.

We respond physically because a connection exists between our imagination and our physical response. When we say things in our speech that cause a physical response, the audience becomes actively engaged with our talk.

Stories Help the Audience Become Emotionally Engaged

“Emotions are the condiments of speech,” according to speech coach Nancy Duarte. They add spice and flavor to your talk. Emotions such as passion, vulnerability, excitement, and fear are particularly powerful. Researchers at Ohio State have a word for that sense of being carried away into the world of a story. They call it transportation. Their research demonstrated that people can get so immersed in a story they hardly notice the world around them. Audiences can be transported by stories as facts and stories as fiction. Narrative transportation theory proposes that when people lose themselves their intentions and attitudes may change to align with the characters in the story. As speakers, our goal should be to help our audience get lost in the story. Sometimes that means telling our own stories, sometimes it means telling the stories of others, and other times telling a hypothetical story.

You’ve probably heard of an fMRI. It’s the machine that measures blood flow to the brain. Scientists used fMRI machines to measure what happened when someone is telling a story and when someone is listening to that story. What they found is exciting. When they compared the speaker’s brain to the listener’s brains, they noticed the brains were lighting up in the same places. When the speaker described something emotional, the audience was feeling the emotion and the emotional centers of their brains were lighting up. Princeton researcher, Uri Hanson calls this brain synching, “neural coupling.”

Consider a study at Emory University that noticed differences in how brains respond to texture words, “she had a rough day” versus non-texture words “she had a bad day.” The texture words activated sensory parts of the brain. When telling a story, find creative and tactile descriptions to engage your audience.

Texture Words

Nontexture words

He is a smooth talker He is persuasive The logic was fuzzy The logic was vague She is sharp-witted She is quick-witted She gave a slick performance She gave a stellar performance She is soft-hearted She is kind-hearted

Imagine you pull up to a flashing red stoplight at an intersection. Seeing it in your mind activates the visual part of your brain. Now, imagine a loved one giving you a pat on the back. Once you imagine it, your tactile center will light up. This is quite powerful when you think about it. When you hear a story, you don’t just hear it, but you feel it, visualize it, and simulate it.

Dopamine, oxytocin, and endorphins are what David Philips calls the “angel’s cocktail.” He suggests speakers should intentionally create stories to activate each of these hormones. By telling a story in which you build suspense, you increase dopamine which increases focus, memory, and motivation. Telling a story in which the audience can empathize with a character increases oxytocin, the bonding hormone which is known to increase generosity and trust. Finally, making people laugh can activate feel-good endorphins which help people feel more relaxed, more creative, and more focused.

Because of neural coupling (our brain waves synching) and transportation (getting lost in a story), the audience members begin to see the world of the person in the story. Because of hormonal changes, they feel their situation and can empathize. A thoughtfully crafted story has the power to help the audience believe in a cause and care about the outcome.

Time and time,

when faced with the task of persuading a group of managers

to get enthusiastic about a major change,

storytelling was the only thing that worked.

Steve Denning, the Leaders Guide to Storytelling

Stories Inspire Action

The conventional view has always been when you speak, you try to get the listeners to pay attention to you. The way you get them to pay attention is to keep the little voice inside their heads quiet. If it stays quiet, then your message will get through. Stephen Denning in The Leader’s Guide to Storytelling suggests an alternative view. He challenges speakers to tell stories to work in harmony with the voices in people’s heads. He says that you don’t want your audience to ignore their voice; you want to tell a story in a way that awakens their little voice to tell its own story. You awaken their voice and then you give it something to do. He advocates using stories as springboards to help the audience think about situations so they can begin to mentally solve problems. In this way, you are not speaking to an audience but rather you are inviting the audience to participate with you.

Consider this story told by Jim Ferrell about the local garbage man and how it engages you and creates both mental images and new ideas.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_phMQY_3S8&fbclid=IwAR1zogB-TdWyNOD9Wib6mVWNdSzuNQ4yJ3cc6rj_Wa38PokqwhUpEPgvX8Q

Stories Help the Ideas Stick in a Way that the Audience Remembers and Understands

Steven Covey, considered one of the twenty-five most influential people by Time Magazine, teaches on business, leadership, and family. In his books and seminars, he uses stories to help the audience remember his lessons. In this video, Green and Clean, he uses a story to help the audience understand servant leadership. As you watch, ask yourself if you will remember this story and the lesson that it offers?

Stories Help Win Law Cases–Example of a Story Analogy

Gerry Spence is considered one of the winningest lawyers and he credits his ability to tell stories to his success. In this video clip, you can see him in action as he tells this jury the story of the old man and the bird. Imagine yourself as a member of the jury, how might this affect you?

“Here’s the story of the bird that some of you wanted to hear again. This is one I’ve used many, many times. It’s a nice method by which you can transfer responsibility for your client to the jury. Ladies and gentlemen, I am about to leave you, but before I leave you I’d like to tell you a story about a wise old man and a smart-alec boy. The smart-alec boy had a plan, he wanted to show up the wise old man, to make a fool of him. The smart-alec boy had caught a bird in the forest. He had him in his hands. The little bird’s tail was sticking out. The bird is alive in his hands. The plan was this: He would go up to the old man and he would say, “Old man, what do I have in my hands?” The old man would say, “You have a bird, my son.” Then the boy would say, “Oldman, is the bird alive or is it dead?” If the old man said that the bird was dead, he would open up his hands and the bird would fly off free, off into the trees, alive, happy. But if the old man said the bird was alive, he would crush it and crush it in his hands and say, “See, old man, the bird is dead.” So, he walked up to the old man and said, “Old man, what do I have in my hands?” The old man said, “You have a bird, my son.” He said, “Old man, is the bird alive or is it dead?” And the old man said, “The bird is in your hands, my son.” Ladies and gentlemen of the jury my client is in yours.” Gerry Spence

Stories Help People Engage With Topics

Alan Alda founded the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science because he wanted to help scientists learn how to best communicate what they know to a lay audience. In this video clip, he shares his lesson on using stories to draw in an audience.

Example from a Corporate Trainer

The Leader Who Withheld Their Story

by Robert “Bob” Kienzle

Our communication training firm was hired to conduct a storytelling workshop for a major client. I quickly realized a major problem: the leader refused to tell a story in the storytelling workshop. We brought the water to the horse and the horse wouldn’t drink. Read the full story of Bob explaining how he taught one of his corporate clients to use storytelling.

Story Changes the Brain Chemistry in Listeners

Paul Zak told audience members a story and then measured the chemicals their bodies released during this story. His conclusion is that story changes brain chemistry and makes individuals more empathetic. In this case, they were more likely to donate money to charity. Watch this video as Zak talks about a universal story structure that includes exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and denouement.

Stories Can Have Drawbacks

While storytelling can be used positively, it can have drawbacks. A story can be more memorable than the point. If the audience remembers your story without the purpose of the story, you missed it. In the teacher’s study mentioned before, students had better short-term recall when the teacher told a narrative. The study also reported that listening to stories increased student cognitive load and some students basically used up their “brainpower” to remembering extraneous information instead of the lesson. The lesson here is to make sure the story reinforces a point and to make sure that the point is clear.

Because stories draw people in emotionally, there can be ethical challenges. Is it ethical to tug at an audience’s heartstrings to get them to donate money? How about giving you money? Speakers need to consider the ethical obligation to consider the impact of the story. Stories tap into emotions and create lasting memories. Stories told with the wrong motives can be manipulative.

The Formula for a Good Story

Tension-Release

So now you see the clear advantage in telling a story, let’s talk about the formula for a good story. A good story should help the audience see the events in their mind’s eye. Your story should play out like a movie in their head. This movie happens because you help them see the setting, characters, and details. To be fully engaged, the audience must feel some sort of tension.

The formula is tension and release.

The best stories create tension or conflict and then in some way resolve conflict. In persuasion, a story can create tension that can be released only by acting on the persuasion. Haven defines a story as “A character-based narration of a character’s struggles to overcome obstacles and reach an important goal.” Notice the focus on struggle and overcoming the struggle. Once you decide on the story that you want to tell, work on helping the audience feel the tension and release.

If the point of life is the same as the point of a story, the point of life is character transformation. If I got any comfort as I set out on my first story, it was that in nearly every story, the protagonist is transformed. He’s a jerk at the beginning and nice at the end, or a coward at the beginning and brave at the end. If the character doesn’t change, the story hasn’t happened yet. And if story is derived from real life, if story is just condensed version of life then life itself may be designed to change us so that we evolve from one kind of person to another.

Donald Miller, A Million Miles in a Thousand Years: What I Learned While Editing My Life.

Dale Carnegie’s formula for storytelling includes three parts: Incident, action, and benefit. In the incident phase, the storyteller shares a vivid personal experience relevant to the point. Next, they give the action phrase, and they share the specific action that was taken. Finally, the speaker tells the benefit of taking the action. It still fits the tension-release formula, it just expands it to make sure that the speaker clearly lets the audience know what conclusion they are supposed to draw.

Dave Lieber illustrates this tension and release in his opening story and explains how it works. (You have to watch only the first five minutes to get the point, but I warn you it is hard to stop listening once he has you hooked) According to Dave Lieber, the formula is to meet the character; there is a low part in the story; the hero pushes up against the villain and overcomes.

Good stories represent a change

One part of the tension-release model is how the character changes. Matthew Dick Moth storytelling champion suggests that stories, where no change took place in the storyteller, are just anecdotes, romps, drinking stories, or vacation stories, but they leave no real lasting impression.

The story of how you’re an amazing person who did an amazing thing and ended up in an amazing place is not a story, it is a recipe for a douchebag. The story of how you are a pathetic person who did a pathetic thing and remained pathetic, is also not a story, it is a recipe for a sadsack. You should represent a change in behavior, a change in heart, a change in attitude. It can be a small change or a very large change. A story cannot simply be a series of remarkable events. You must start out as one version of yourself and end as something new. The change can be infinitesimal. It need not reflect an improvement in yourself or your character, but change must happen.

Matthew Dick.I once was this, but now I am this

I once thought this, but now I think this

I once felt this, but now I feel this.

I once was hopeful, but now I am not

I once was lost, but now I am found

I once was happy, but now I am sad

I once was sad, but now I am happy

I once was uncertain, but now I know

I once was angry, but now I am grateful

I once was afraid, but now I am fearless

I once doubted, but now I believe

Stories Often Follow Common Plots

According to Heath and Heath of Made to Stick, there are common story plots. Each of these can be used in most speech types and can be adapted to the tension-release model.

Challenge Plot

- Underdog story

- Rags-to-riches story

- Willpower over adversity

Challenge plots work because

they inspire us to act.

- To take on challenges

- To work harder

Connection Plot

- Focusing on relationships

- Making and developing friendships

- Discovering and growing in love

Connection plots work because

they inspire us in social ways.

- To love others

- To help others

- To be more tolerant of others

Creativity Plot

- Making a mental breakthrough

- Solving a longstanding puzzle

- Attacking a problem in an innovative way

Creativity plots work because

they inspire us to do something differently.

- To be creative

- To experiment

- To try something new

Elements to a Good Story

For the audience to experience the tension and release, they must be invested in the story. Good stories help the audience see the setting, know the characters, and feel the action.

1. Setting

Think of the setting as a basket to hold your story. If you start with the basket, the audience has a place to hold all the other details you give them. For this reason, many storytellers begin by describing the setting.

2. Characters

When you describe how the characters look or how they felt, we can see them as if we are watching them in a movie. The trick is to tell enough details we can create a mental picture of the character without giving so much information that we get bogged down.

3. Action

When you describe the action that is taking place, the audience begins to feel the action. If you describe something sad that happened, the audience will feel the sadness. If you describe something exciting that happened to you or a character, the audience will feel that excitement.

Watch the first two minutes of this video and notice how Matthew starts with the setting and the characters and you can see the events unfold. You can see the action take place in your mind’s eye and you become invested in his story.

Flavor Crystals–The Little Extras

As a child, I used to love breath mints that would have blue flecks in them. They were called flavor crystals and they were there as little taste surprises that would enhance the flavor. You can enhance your story with little flavor crystals–little details that make it more interesting. Flavor crystals are those extra details that will impact your audience.

Ruben Gonzalez and Olympic Champion luger is a motivational speaker. As you watch this video clip, notice how he incorporates details in his story so we can see what’s happening.

Make Sure Your Story is Relatable

When you pick your story, make sure that you pick themes others can relate to in some way. Watch World Champion Presiyan Vasilev and notice how he uses little examples that everyone can relate to, like how you always get a flat tire when you are dressed up.

Why do flat tires always happen when you’re dressed up? Is there something collapsed in your life? Your knowledge may be limited. Your skills may be rusty. But no doubt, you will be changed when you reach out.

Do This: Keep a Story Log

Notetaking Challenge

Matthew Dicks suggests sitting down every day and asking yourself, “What happened today that is storyworthy?” Keep a notebook and write down a few ideas every day.

The Magical Science of Storytelling TED Speaker David Philips has a similar suggestion. He encourages people to not only write down your stories but you index them based on the emotional reaction you wanting to get.

Theory Application

Literary theorist Kenneth Burke asks us to think of life as a drama where people are actors on a stage. What is their motivation for what they do and what they say? He offered five strategies for viewing life that he called dramatistic pentad.

-

- Act: What happened? What is the action? What is going on? What action; what thoughts?

- Scene: Where is the action happening? What is the background situation?

- Agent: Who is involved in the action? What are their roles?

- Agency: How do the agents act? By what means do they act?

- Purpose: Why do the agents act? What do they want?

How does all this relate to telling a story in a speech? The first thing you can do is to use this list when brainstorming how to fully develop your story. You can also use it as a way to evaluate the completeness of your story. The third way to use it is as a tool to evaluate your audience and how they view life. Why do they do what they do and what do they need to hear in order to be inspired, motivated, or persuaded?

In this TED Talk, My Invention that Made Peace with Lions, Richard Turere makes the audience wonder how a problem like lions killing livestock can possibly be solved. Richard draws us into his story and makes us want to know how a young boy could solve such a large problem. Watch this video and see if you can apply each of Burke’s Five Items.

Key Takeaways

Remember This!

- A story is a powerful tool because it engages the audience on not just a logical but also an emotional level.

- Good stories offer a setting, a description of the characters, and add enough detail for the audience to see the story take place in their mind’s eye. The action of a story should be told in a way that the audience can see the events unfold in their mind’s eye.

- Good stories have tension and release.

- Good stories have characters and situations that demonstrate a change.

Please share your feedback, suggestions, corrections, and ideas.

I want to hear from you.

Do you have an activity to include?

Did you notice a typo that I should correct?

Are you planning to use this as a resource and do you want me to know about it?

Do you want to tell me something that really helped you?

Bonus Features

There is so much information on this topic, that I struggled with what to include and what to leave out or put as optional. Here are a few videos that I like to think of as the BONUS FEATURES. In addition, there is a supplemental chapter on story that includes more videos and activities.

The Magical Science of Storytelling

David Philips uses stories to illustrate how storytelling can activate what he calls the angel’s cocktail: dopamine, oxytocin, and endorphins.

Angel’s Cocktail

- Dopamine

- What it does: Increases focus, motivation, memory.

- How to do it: Build suspense, launch a cliffhanger, create a cycle of waiting and expecting.

- Oxytocin

- What it does: Increases generosity, trust, bonding.

- How to do it: Create empathy for whatever character you build.

- Endorphin

- What it does: Increases creativity and focus and people become more relaxed.

- How to do it: Make people laugh.

The Structure of Story

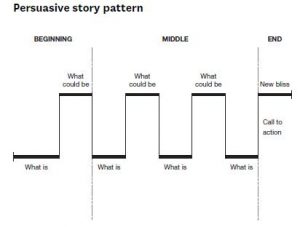

Nancy Duarte studied hundreds of speeches and found the same storytelling technique. In her TED talk, she provides this chart. It is a story that is easy to digest, remember and retell.

Figure 1: Nancy Duarte-Persuasive Story Pattern

INSERT VIDEO: NANCE DUARTE THE SECRET STRUCTURE OF GREAT TALKS

https://www.ted.com/talks/nancy_duarte_the_secret_structure_of_great_talks?language=en

Examples of Storytelling

- Storytelling in a Eulogy: Brook Shield’s Eulogy to Michael Jackson: https://youtu.be/vpjVgF5JDq8

- Storytelling in Business: Steve Denning Discovered the Power of Leadership: https://youtu.be/qiVBcD5M3yc

- Storytelling and Education: Speak Less, Expect More. Matthew Dicks: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sK2P2NEIXUE

REFERENCES

Alda, A. (2017). If I understood you, would I have this look on my face? Random House.

Alda, A. (2017). Knowing how to tell a good story is like having mind control. Big Think. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4k6Gm4tlXw Standard YouTube License.

Bezos, M. (2011). A life lesson from a volunteer firefighter. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.ted.com/talks/mark_bezos_a_life_lesson_from_a_volunteer_firefighter?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare Standard YouTube License.

Bolte-Taylor, J.92008). My Stroke of Insight. Ted Talk. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.ted.com/talks/jill_bolte_taylor_my_stroke_of_insight?language=en Standard YouTube License.

Braddock, K., Dillard, J. P. (25 February 2016). Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs, 83 (4), 446–467. doi:10.1080/03637751.2015.1128555. S2CID 146978687.

Brooks, D. (2019). The lies our culture tells us about what matters–and a better way to live. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.ted.com/talks/david_brooks_the_lies_our_culture_tells_us_about_what_matters_and_a_better_way_to_live?language=en Standard Youtube License.

Burke, K. (1945). A grammar of motives. Berkeley: U of California Press.

Carnegie, D. (2017). The art of storytelling. Dale Carnegie & Associates ebook.

Covey, S. (2017). Green and Clean. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8MylQ_VPUI Standard YouTube License.

Dahlstrom, M,F. (2014). Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(4), 13614–13620. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1320645111

Denning, S. (2005). The leader’s guide to storytelling: Mastering the art and discipline of business narrative. John Wiley and Son.

Denning, S. (2001). The springboard: How storytelling ignites action in knowledge-era organizations. Taylor & Francis.

Dicks, M. (2018). Storyworthy: Engage, teach, persuade, and change your life through the power of storytelling. New World.

Dicks, M. (2016). This is Gonna Suck. Moth Mainstage. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N3J4Q5c1C1w Standard YouTube License.

Duarte, N. (n.d.) Fifteen Science-Based Public Speaking Tips to be a Master Speaker, The Science of People. https://www.scienceofpeople.com/public-speaking-tips/.

Ferrell, J. (2017). An outward mindset for an inward world. Jim Ferrell Keynote. The Arbinger Institute. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_phMQY_3S8 Standard YouTube License.

Fisher, W.R. (2009). Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communication Monographs, 51 (1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758409390180

Fisher, W.R. (1985). The Narrative Paradigm: In the Beginning, Journal of Communication, 35(4), 74-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1985.tb02974.x

Gallo, C. (2016). I’ve analyzed 500 TED Talks, and this is the one rule you should follow when you give a presentation. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/ted-talk-rules-for-presentations-2016-3

Gershon, N, & Page, W. (2001). What storytelling can do for information visualization. Communication of the ACM, 44, 31–37.https://doi.org/10.1145/381641.381653

Gonzales, R. (2011). Three-time Olympian, peak performance expert. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qqMOrjsRUT4. Standard YouTube License.

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of personality and social psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701

Green, S. J., Grorud-Colvert, K. & Mannix, H. (2018). Uniting science and stories: Perspectives on the value of storytelling for communicating science. Facets, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2016-0079

Hasson, U., Ghazanfar, A.A., Galantucci, B., Garrod S, & Keysers C. (2012). Brain-to-brain coupling: a mechanism for creating and sharing a social world. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(2), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.12.007

Haven, K. (2007). Story proof: The science behind the startling power of story. Kendall Haven.

Heath, C & Heath, D. (2008). Made to Stick. Random House.

Homo Narrans: Story-Telling in Mass Culture and Everyday Life. (1985). Journal of Communication, 35 (3) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1985.tb02973.x

Kromka, S. M. & Goodboy, A. K. (2019) Classroom storytelling: Using instructor narratives to increase student recall, affect, and attention, Communication Education, 68:1, 20-43. DOI: 10.1080/03634523.2018.1529330

Lacey, S., Stilla, R., & Sathian, K. (2012). Metaphorically feeling: comprehending textural metaphors activates somatosensory cortex. Brain and language, 120(3), 416–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2011.12.016

Lieber, D. (2013). The power of storytelling to change the world. TEDtalk. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Bo3dpVb5jw Standard YouTube License.

Miller, D. (1994). A million miles in a thousand years: How I learned to live a better story. Thomas Nelson.

Philips, D. (2017). The magical science of storytelling. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nj-hdQMa3uA Standard YouTube License.

Reynolds, G. (2014). Why storytelling matters TED. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YbV3b-l1sZs Standard YouTube License.

Simmons, A. (2001). The story factor: Inspiration, influence, and persuasion through the art of storytelling. Basic Books.

Spencer, G. (1995). How to argue and win every time. St. Martin.

Spence, G. (2018). Persuasive storytelling for lawyers by Alan Howard. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rzdoR2PJqYg Standard YouTube License

Turere, T. (2013). My invention that made peace with lions. TED. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RAoo–SeUIk Standard YouTube License.

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why Don’t Students Like School?: A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

Zac, P.J. (2014). Why your brain loves good storytelling. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/10/why-your-brain-loves-good-storytelling

Zac, P.J. (2012). Empathy, neurochemistry, and the dramatic arc: Paul Zac and the future of storytelling. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q1a7tiA1Qzo Standard YouTube License.

Media Attributions

- Sitting around a campfire © Ball Park Brand is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Voices in your head is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Formula for a story © Lynn Meade is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Take Notes

- Persuasive Story Pattern