22 Public Health (part 2)

By Alyssa Riley and Dave Bostwick

In the previous section about public health and mass media, we primarily looked at advertisements for vaping, cigarettes and alcohol. In this section, we’ll examine these additional topics:

- food ads and packaging

- the mukbang phenomenon

- ads for weight-loss products

- unhealthy body standards portrayed in media

- effects of social media on mental health

- the relationship between body image and mental health, especially for females

YOUR MEDIA LANDSCAPE

Chapter 17 on advertising briefly looked at how advertisers sometimes use weasel words to make product claims that can’t be proven. Here are a few examples of weasel words for food products:

- natural

- organic

- fortified

- low-fat

- real

- no added sugar

To what extent do ads and packaging that include these types of terms influence your purchasing decisions for food and drink products?

FOOD PACKAGING AND ADS

Since the passing of the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act, which “marked a monumental shift in the use of government powers to enhance consumer protection,” the U.S. government has required that food and drug companies truthfully label their products. However, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) cannot always protect consumers by simply removing dangerous drugs from the market, proving that product claims are misleading, or penalizing companies for fraudulent products and marketing. Plus, lengthy court cases are often involved in order for the FDA and FTC to prove deception.

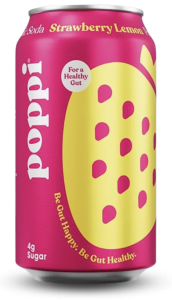

For example, promotional text for Poppi told consumers they could “get all the soda feels with 5g sugar, ingredients you can love and prebiotics.” Poppi faced criticism – and even a lawsuit – for advertising and packaging claims that the product benefits gut health. According to Today, a California woman filed a lawsuit that included the following assertion:

For example, promotional text for Poppi told consumers they could “get all the soda feels with 5g sugar, ingredients you can love and prebiotics.” Poppi faced criticism – and even a lawsuit – for advertising and packaging claims that the product benefits gut health. According to Today, a California woman filed a lawsuit that included the following assertion:

Poppi’s promises that its prebiotic soda is a good alternative to conventional sugar-loaded sodas are misleading. The product claims to be “gut healthy” due to its inclusion of “prebiotics,” but there’s not enough prebiotic fiber in a single can to produce “meaningful gut health benefits.”

Although Poppi representatives refuted the claims in the lawsuit, the branding that once claimed the product’s support for gut health is no longer on cans or the Poppi website. Poppi eventually agreed to an $8.9 million settlement of a class-action lawsuit.

A New York Times feature on “gut soda” said that “the jury’s still out” on whether prebiotic sodas contain enough fiber to have significant gut health benefits. Gary Wenk, a psychology and neuroscience professor at Ohio State University, said these drinks can still be a better choice than traditional soda because of fewer sweeteners.

Poppi is certainly not the only brand to be accused of using misleading labels on products, and consumers sometimes must conduct their own research about truthful packaging.

MISLEADING FOOD ADS FOR KIDS

In the 21st century, obesity has garnered publicity as a nationwide health concern. One noted research study said that messages persuading people to adjust their behavior sometimes depict regret or disgust. However, other campaigns that confront obesity replace or augment depictions of obesity and excessive eating with “positive promotion of healthy food items.”

The study said that crafting messages about “making the healthy food choice the easy choice” can be effective.

Another frequently cited research study focused on some fast-food restaurants’ promotion of unhealthy meals by offering collectible toys, known as the Happy Meal Effect. According to the study’s conclusion, public policies that restrict toy premiums to meals that meet nutritional standards may promote healthier eating at fast-food restaurants.

For historical perspective, here’s one or the earliest ads for the McDonald’s Happy Meal (1979).

SUPER-SIZED OR NOT?

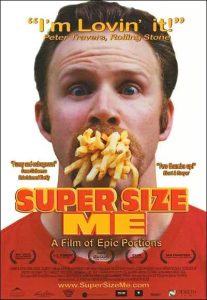

The 2004 award-winning documentary film Super Size Me showed director Morgan Spurlock eating nothing but McDonald’s fast food. The documentary was routinely shown to school-aged children as a warning about the negative effects of fast food, including potential obesity.

The 2004 award-winning documentary film Super Size Me showed director Morgan Spurlock eating nothing but McDonald’s fast food. The documentary was routinely shown to school-aged children as a warning about the negative effects of fast food, including potential obesity.

However, the accuracy of Spurlock’s documentary research came into question when he later admitted that he was also drinking alcohol during the month that the documentary was made. Also, other researchers could not replicate Spurlock’s one-month weight gain or the extent of the negative impact that a McDonald’s-only diet had on his body as shown in the documentary.

Nonetheless, public health concerns surrounding unhealthy eating persist today, and for good reason. One in five children were considered obese in 2024, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In the previous chapter, you watched videos created by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Below is a brief example of how the CDC’s public-health messages can have a trickle-down effect to content generated by other news outlets (in this case KTVB in Boise, Idaho).

THE MUKBANG PHENOMENON

Social media plays a role in current attitudes toward overeating. For example, a mukbang is a live-streamed video that shows a host eating large amounts of food. The videos can include “slurps, loud chewing, crunching, and all those sounds that come hand-in-hand with enjoying a good meal.”

One notable mukbanger, Nicholas Perry, became known as Nikocado Avocado on Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok. You can view part of Perry’s video below as an example of a mukbang.

Originally a vegan, in 2014 Perry began creating and posting videos about his dietary lifestyle. When mukbang videos became popular, he gave up being a vegan and adopted the mukbang trend. In the process, Perry told audiences that he gained more than 200 pounds, causing a tsunami of criticism against mukbangs.

However, in 2025, Perry said that, through several medical procedures, he had removed at least 10 pounds of excess skin following dramatic weight loss of more than 200 pounds. NBC News reported that Perry admitted to “hiding my loose skin by positioning my body at certain angles, like paying close attention to my clothing and the lighting, but the truth is, I have loose skin in my abdomen, arms, legs, my torso, back, even my neck.”

The video below from All Things Nutrition explains the history and negative consequences of the mukbang trend.

IF WEIGHT-LOSS ADS TOLD THE TRUTH …

Advertisements for pills, diet plans and other products promote rapid weight loss. What if diet advertisements told the truth? The FTC published an article about the truth behind weight loss ads, which included the following advice.

Trying to lose weight? Watch out for false promises. It would be nice if you could lose weight simply by taking a pill, wearing a patch, or rubbing in a cream, but claims that you can lose weight without changing your habits just aren’t true. And some of these products could even hurt your health.

The FTC listed false promises in weight-loss ads, such as these:

- “Lose weight without dieting or exercising.”

- “You don’t have to watch what you eat to lose weight.”

- “You can lose 30 pounds in 30 days.”

Ultimately, these types of product claims are not supported by scientific evidence.

Beyond the gimmicky promises listed above, weight loss is a frequent topic on news and current-events shows. Below is a CBS feature about the potential benefits and risks of some of the more reputable weight-loss drugs that gained popularity in the 2020s.

UNHEALTHY BODY STANDARDS AND EFFECTS ON MENTAL HEALTH

Research has found that adolescents and young adults are at vulnerable ages when the effects of social media content can be especially harmful.

According to a research analysis from the National Library of Medicine, “As they strive to establish their self-identity, the inundation of idealized and often unattainable beauty standards on platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok can distort their perceptions of normalcy and attractiveness.”

Because of social media, Gen Zers – primarily females – struggle with self-esteem, feeling the urge to conform to unhealthy beauty standards and practices promoted by other social media users and many influencers. Unhealthy standards for beauty can lead to eating disorders, distorted body image and mental health concerns.

Some 21st-century public-health research has analyzed the impact of the thin-ideal media image on women. One study included these observations:

- The thin-ideal woman often portrayed in the media is typically 15% below the average weight of women, representing an unrealistic standard of thinness (tall, with narrow hips, long legs, and thin thighs).

- This ideal stresses slimness, youth and androgyny, rather than the normative female body. The thin-ideal woman portrayed in the media is biogenetically difficult, if not impossible, for the majority of women.

- Theorists have argued that this image, combined with our culture’s intense focus on dieting, has contributed to the current epidemic of eating disorders.

For example, a TikTok trend called “What I Eat in a Day” may find its way to a 20-year-old woman struggling with body image. When she sees another woman eating small portions of ultra-healthy food, she may think she has to do the same to be attractive and then subsequently struggle with her body image and mental health.

Some health-related companies produce their own content about public-health concerns, including body image. CVS maintains a YouTube channel and produced the video below.

SOCIAL MEDIA AND MENTAL HEALTH

Reliable research about the effects of social media usage can take years to compile. By the time a study is complete, it can already seem outdated in relation to current social media trends. Nonetheless, it’s important to understand those effects, even if studying research results can feel like looking in a rear-view mirror.

The following video from ABC News examines how social media may negatively impact teenagers’ mental health.

A research study published in the medical journal JAMA revealed a statistical connection between addictive screen use (often through social media or video games) and suicide or suicidal thoughts among U.S. youth.

However, addiction was not always based on amount of screen time. Instead, children who showed signs of addictive screen use said that they did not want to leave their screens or felt the need to increase their use of the technology.

In a Pew Center Research survey, 45% of U.S. teens said they spend too much time on social media. Roughly half of teens (48%) said that social media sites have a mostly negative effect on people their age, but only 14% think they are negatively affected themselves. This echoes separate research from chapter 1 showing 70% of surveyed college students said they have somewhat high or very high media literacy skills, but only 32% rated the media literacy of their peers as somewhat high or very high.

Among adults, a commonly used term related to screen addiction is doomscrolling. According to BottomLine, doomscrolling can be defined as “habitually scrolling through news feeds and social media for the latest bad developments.” Clinical research shows that doomscrolling can increase anxiety, worsen depression and affect sleep quality. In surveys of U.S. adults, approximately 30% say they doomscroll either “a lot” or “some of the time.”

Wired magazine published suggestions to limit doomscrolling, including these simple strategies:

- Turn off notifications.

- Put your phone in another room for hours at a time.

- Set screen time limits within your phone’s operating system.

- Set a bedtime for your phone.

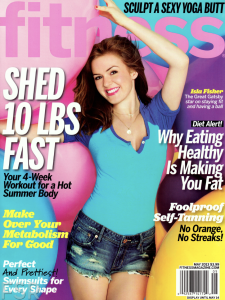

WOMEN IN MAGAZINES

Media content’s negative effects on mental health can also be caused by an older but still prevalent media form. Magazines that cover celebrity news, human-interest stories and pop culture – such as People and Us – can seem obsessed with gossip about which celebrities have lost or gained weight, who is experiencing the best body of their lives, and who doesn’t look so good in swimsuit photographs taken by paparazzi.

Media content’s negative effects on mental health can also be caused by an older but still prevalent media form. Magazines that cover celebrity news, human-interest stories and pop culture – such as People and Us – can seem obsessed with gossip about which celebrities have lost or gained weight, who is experiencing the best body of their lives, and who doesn’t look so good in swimsuit photographs taken by paparazzi.

Click through the following links to view examples and analysis of magazine covers featuring body transformations of public figures:

- No Fat Moms! Celebrity Mothers’ Weight-Loss Narratives in People Magazine

- Are Diet Companies Moving Away From Celebrity Endorsements?

- Hot Shots: Jennifer Hudson Shines in ‘Self’ Magazine

Taylor Swift voiced her concerns in her Miss Americana documentary. And in an interview with Variety, Swift said this:

I remember how, when I was 18, that was the first time I was on the cover of a magazine. And the headline was like ‘Pregnant at 18?’ And it was because I had worn something that made my lower stomach look not flat. So I just registered that as a punishment. And then I’d walk into a photo shoot and be in the dressing room and somebody who worked at a magazine would say, “Oh, wow, this is so amazing that you can fit into the sample sizes. Usually we have to make alterations to the dresses, but we can take them right off the runway and put them on you!” And I looked at that as a pat on the head. You register that enough times, and you just start to accommodate everything towards praise and punishment, including your own body.

Judgmental analysis of celebrities’ bodies not only affects the celebrities themselves, it also leads impressionable audiences to compare their bodies to what they see on magazine covers and in photo spreads.

CONCLUDING THOUGHT

Social media can be a good place to build community, but it doesn’t replace the need for public health professionals.

Journalist and media critic Steven Brill cited research showing that when social media users have searched for health care information, “the machines designed to entice the most engagement promoted posts by people with alarmist opinions over posts by doctors or dentists.”

Brill also offered his perspective about relying on the internet and social media for guidance on personal health.

When you’re getting brain surgery or wondering about a vaccine, you should want a certified brain surgeon or epidemiologist to advise you, not someone with an angry or paranoid opinion that generates the most likes and shares.

In response to growing concerns over medical misinformation on TikTok, Fox 32 in Chicago produced the video segment below. The video summarized research showing that the majority of social media influencers who gave medical advice on TikTok were not doctors. The conclusion noted, however, that social media can be a good place for some people to find emotional support.

Medical professionals suggest calling a doctor for health concerns and using social media to find a community of other people that may suffer from a condition that you have.

TRUE or FALSE

The following questions highlight a few tidbits of information from the chapter. Use the forward button or click on sections of the control bar to advance through the questions.

FOOD PACKAGING AND PROMOTION

For this assignment, you can analyze either packaging for a food product or an advertisement for a food product. The packaging or advertisement should include text that makes a claim that is not provable.

Analyze your ad based on the following questions.

- What product is advertised?

- Which text is not easily proven true or false?

- In what ways does the text in question encourage consumers to think favorably about the health benefits of the product?

- Do consumers face any potential health risks if they consume this product without doing their own research on the reliability of the text in question?

- What else do you think is noteworthy about the ad content?

If you are submitting this as a class assignment, you should include a visual or a link for the product packaging or advertisement.

Use a Q&A format with at least two detailed sentences for each response.