21 Public Health (part 1)

By Alyssa Riley

INTRODUCTION

Through billboards, social media posts and other online ads, content about public health permeate my daily life, spreading mixed messages about mental, physical and dietary health.

Growing up, my sisters and I were regular customers of clothing stores like Hollister and Abercrombie & Fitch. Even in my youthful preteen years, I noticed that their models were all exclusively a size 2 and below..

Today, as clothing brands like Brandy Melville are more inclusive of all shapes and sizes, it’s still impossible to avoid some depictions of wafer-thin models.

I’ve also seen social media content creators in the 2020s who have been obsessed with the mukbang trend, posting videos of themselves overeating – often unhealthy foods – for views. Conversely, other content creators and influencers idealize losing weight quickly and “glowing up,” sometimes to attain unhealthy body standards.

When I was 15 years old with my first part-time job and bank account, I stumbled across an advertisement for fast-acting weight loss pills. I was at a perfectly healthy weight for my age, but I was naïve and impressionable. I purchased the pills and, ultimately, got my bank account hacked because of it.

Today, “fast-acting weight loss pills” still flood the Internet. Even more alarming, celebrity magazines such as People and Us often include content about the weight loss or gain of celebrities, scrutinizing their physiques or promoting an unrealistic diet culture.

Much like during the mid-20th century when advertisements used doctors and attractive models to promote the health benefits of cigarettes (granted, the world did not yet have the complete scientific evidence to prove otherwise), vaping companies today utilize the “healthier alternative” argument to advertising their addictive, nicotine-packed devices. Moreover, they target youth with student discounts, fun flavors, reward systems, and catchy phrases like “social buzz.”

While promoting the best skin care routines, diet plans, or other products for consumption, some U.S. advertisers and other content creators target vulnerable demographics to mislead audiences. As a result, media literacy is no longer limited to news. It has expanded into the realm of public health.

As William L. Roper, a former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), once said, media content “is vital in conveying health information to the public, changing people’s perceptions of what’s healthy and what’s not.”

As an example of a public-health message direct from the CDC, below is a video about the risks of mixing drugs.

The field of public health faces the same struggles with verification and trust that you’ve seen in previous chapters. For example, a 2025 White House report about children’s health released by the Make America Healthy Again Commission initially contained references to supporting scientific papers that did not exist.

As another example, the spread of anti-vaccine content, mostly through social media, led to the most confirmed U.S. cases of measles in this century in 2025. Also, CDC research showed that vaccinations among American kindergartners decreased for all reported vaccines during the 2024-2025 school year.

As parents see an increase in anti-vaccine content through media sources, they are more likely to request exemptions for their children. In Arkansas, approximately 3.5% of kindergartners had non-medical exemptions for vaccines in the 2024-25 school year. This reflected a trend of increases since the 2014-15 school year, when just 1.2% of Arkansas kindergartners had a non-medical exemption, according to the CDC.

In 2025, the Arkansas Department of Health reported cases of measles in the state. Arkansas had not previously reported a case of measles since 2018.

Media professionals who cover public health must provide information to increasingly skeptical audiences who may have become confused by conflicting guidance about vaccines, nutrition, addiction and more. Here’s a New York Times’ description of the landscape.

Americans have always been ambivalent about public health in general and the American regulatory project in particular. We want protection from bad food and bad medicine and other unsafe products, but we also want to draw the line between safe and unsafe for ourselves and to redraw it whenever we see fit.

In the case of vaccinations, it’s easy to see why parents may feel confused. In 2025, Florida officials made plans to end all vaccine mandates around the same time that prominent CDC vaccine officials resigned to protest changes in federal advocacy for vaccination programs. One former researcher explained that broader diagnosis standards for autism during the ‘80s and ‘90s led to higher autism rates, unrelated to childhood vaccinations.

How can media professionals improve their approach to offering reliable content about public health, including vaccinations?

“Debunking health misinformation isn’t just about correcting false claims,” Naseem Miller, the senior health editor at The Journalist’s Resource, wrote. “It’s about building trust, choosing words with care, and meeting people where they are, without compromising the facts.”

YOUR MEDIA LANDSCAPE

To what extent does media content, including social media, affect your health habits? Do any specific examples come to mind? Have you encountered conflicting media guidance about health-related topics?

INTRODUCTION TO PUBLIC HEALTH

The brief presentation below provides an overview of many goals of the public health profession based on content from the American Public Health Association.

Study the following presentation slides by using the forward button or clicking on sections of the control bar. To enlarge any interactive presentation in this book, click on the lower-right full-screen option (arrows).

Beyond traditional advertising and news content, many 21st-century U.S. consumers now offer their own perspectives on public health through social media, user-generated videos or podcasts, and online reviews.

This is the first of two chapters about intersections between public health and the current media landscape. The remaining content in this chapter briefly examines media messages about vaping, cigarettes and alcohol.

VAPING ADS

Vaping has become a health concern for U.S. teenagers. One research study said that “most youth (63%) are unsure whether their products contain nicotine.” As a result, they may not know that they are exposing themselves to nicotine through e-cigarettes. This confusion often exists despite warning labels on nicotine products.

Vaping has become a health concern for U.S. teenagers. One research study said that “most youth (63%) are unsure whether their products contain nicotine.” As a result, they may not know that they are exposing themselves to nicotine through e-cigarettes. This confusion often exists despite warning labels on nicotine products.

A University of Arkansas professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminology said, “We’re seeing kids who are developing lung disease and respiratory disease. With smoking, that takes a while.” According to statistics from the Arkansas Center for Health Improvement, 44% of high school seniors in Arkansas said they have tried vaping.

Adding to the nationwide epidemic, vaping advertisements make vapes seem not only healthier than cigarettes – which is only sometimes the case for long-term cigarette smokers – but also more enticing.

In 2020, the Massachusetts attorney general’s office filed a lawsuit alleging that Juul had bought online advertisements on websites for Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network and Seventeen magazine. This lawsuit came amid other accusations that the company targeted underage customers. Eventually, in 2022, Juul settled a multistate youth vaping inquiry for approximately $450 million. Below is an NBC News account of the settlement.

As another marketing example, Blu, also a company that makes vaping products, used the following promo script:

Take back your freedom to smoke when and where you want without ash or smell. Blu is everything you enjoy about smoking and nothing else. Nobody likes a quitter, so make the switch today.

Supportive language such as “freedom,” “enjoy,” and “nobody likes a quitter” leads consumers to believe that a Blu product is a healthy choice that helps them maintain their individuality.

The American Lung Association compiled a list of advertising strategies that companies have developed to target younger users. More locally, some shops even offer discounts to college students.

20TH-CENTURY CIGARETTE ADS

It’s easy to draw a parallel between 21st-century vaping ads and 20th-century cigarette ads. From the 1930s to the 1950s, cigarettes were promoted as a way to stay happy and healthy – specifically for nerves and digestion. When concerns arose about the negative effects of cigarettes, advertisements began to feature recommendations from public figures, doctors and dentists as reassurance about the positive experiences and benefits of smoking. Below is an example.

Largely as a result of successful advertising, cigarettes were popular in America through much of the 20th century, across all social classes and professions. Today, packaging and advertisements for products containing nicotine and tobacco must include a warning label about negative health consequences. Also, the Federal Communications Commission banned cigarette ads from FCC-licensed radio and television broadcasting in 1971.

Some current anti-smoking campaigns use a more modern storytelling style to let people share their instructive stories. Below is a CDC example from a video series titled “Tips From Former Smokers.”

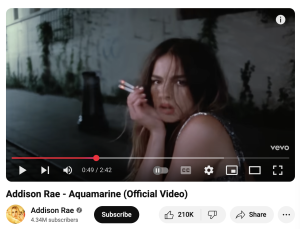

Despite efforts such as the video above, some movies, TV shows and music videos today show scenes that make characters look cool or powerful by smoking. For example, a scene from Addison Rae’s “Aquamarine” video shows her smoking two cigarettes at the same time.

Despite efforts such as the video above, some movies, TV shows and music videos today show scenes that make characters look cool or powerful by smoking. For example, a scene from Addison Rae’s “Aquamarine” video shows her smoking two cigarettes at the same time.

The cigfluencers Instagram account has documented this trend of on-screen smoking.

ALCOHOL ADS

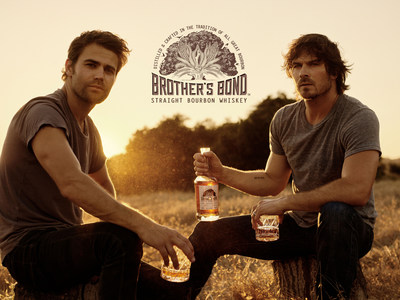

Although the FCC banned cigarette ads from public airwaves, alcohol advertisements still flood television screens, social media platforms and other digital spaces. And the alcohol industry now features influencer-branded products. Just a few examples of this trend include Kendall Jenner’s 818 tequila, Kylie Jenner’s Sprinter vodka seltzer, Kyle Cooke’s Loverboy seltzers, and Brother’s Bond Bourbon from Paul Wesley and Ian Somerhalder, who played the Salvatore brothers in The Vampire Diaries television series.

It is hard not to wonder whether the influential figures promoting their alcohol brands are encouraging more young people to drink alcohol. Non-profit organization Movendi International found that “young people who are exposed to alcohol advertising are more likely to start consuming alcohol at an earlier age and consume alcohol more frequently.”

Movendi also suggested that increased consumption is at least partially due to “celebrities pushing alcohol as an aspirational lifestyle choice.” Below is an ad from Smirnoff featuring Kaley Cuoco.

Despite ads like the one above, public health messages about the risks of drinking alcohol may be influencing U.S. consumers. A 2025 Gallup poll showed that approximately 55 percent of U.S. adults said they consumed alcohol, which was the lowest percentage in the 90 years that Gallup has collected data on drinking behavior. And the poll suggested that Americans who said they drink alcohol were consuming less.

MORE TO COME ABOUT PUBLIC HEALTH

In the next chapter (part 2), we’ll explore food and drink beyond alcohol, body image and mental health.

TRUE or FALSE

The following questions highlight a few tidbits of information from the chapter. Use the forward button to advance through the questions.