1 Opening Concepts

by Dave Bostwick

CURTAIN-RAISER

You’ll be reading some of my personal perspectives in this OER text, so I want to raise the curtain and introduce myself by taking you back to the 1980s when I first attended college. Below is a photo of me singing from way back then (when I had much more hair).

Like a few of my peers, I watched a lot of MTV, which made me want to become an international rock star more than a news journalist. In less than a decade, my generation went from 8-track tapes to cassette tapes to compact discs (CDs). Of course, there was no internet for consumers. Small-screen personal computers were a clunky novelty item, high-quality stereo speakers were huge, and it would have been impossible for us to imagine a streaming service like Spotify.

Like a few of my peers, I watched a lot of MTV, which made me want to become an international rock star more than a news journalist. In less than a decade, my generation went from 8-track tapes to cassette tapes to compact discs (CDs). Of course, there was no internet for consumers. Small-screen personal computers were a clunky novelty item, high-quality stereo speakers were huge, and it would have been impossible for us to imagine a streaming service like Spotify.

I spent my childhood in a rural area of Oklahoma, and my family used a directional TV antennae to pick up one station at a time. For example, if you wanted to watch shows broadcast on a TV station in Wichita Falls, Texas, you had to point the antennae toward Wichita Falls. I remember moving to a larger city and getting a cable TV box connected to a controller with a physical cord. At the time, it seemed almost unbelievable that my roommates and I could sit on the couch and change the TV channel without getting up to turn a control knob.

Regardless of your age, you probably have memories of how media consumption habits have changed in your lifetime. This Open Educational Resource (OER) text will explore how mass media technologies have evolved over several centuries. We’ll also look at how mass media affects users (and vice versa), paying special attention to ethical concerns.

NOTE – To help you reflect on your own media interactions and media literacy, many chapters in this OER text will open with narrative examples and first-person observations (such as the one above).

YOUR MEDIA LANDSCAPE

How would you rate your own media literacy skills?

- very low

- somewhat low

- moderate

- somewhat high

- very high

You can compare your response to a Student Voice survey published in 2025 by Inside Higher Ed and Generation Lab. We’ll discuss this in more detail later in the chapter.

OPENING CONCEPTS

This chapter includes several interactive exercises to introduce some key concepts. Here’s your first flip-card question.

As a current example, it’s an oversimplification to refer to a singular idea of media as liberal or conservative. No single entity controls American media, so it’s best to think of the word media as plural. The U.S. media landscape is extremely diverse in content and ownership. It is not a singular concept, and it includes a variety of liberal and conservative outlets.

Whenever possible, be specific about the type of medium or media outlets that you discuss. In most cases, you should avoid using singular references to “the media.”

THE LONG VIEW OF MEDIA LITERACY

Many of today’s media critics complain that social media platforms devalue accuracy and make it difficult for consumers to gain reliable information. Several chapters will mention this and similar concerns about media literacy.

Here’s a warm-up question to help you think about whether this is a new or old problem.

Franklin wasn’t alone among our founding fathers. John Adams wrote in his diary about “Cooking up Paragraphs” and “working the political Engine!”

The following 2018 audio from National Public Radio details the history of fake news in American journalism, including an example from Pea Ridge, Arkansas.

Fake News: An Origin Story (NPR)

In particular, pay attention to the opening case example and analysis beginning at the 2-minute mark progressing through the brief overview of the Pea Ridge case and the Ida B. Wells example ending at the 10:30 mark.

Later, the NPR audio also mentioned that some audience members seek information that confirms their beliefs or identity, so they (perhaps unconsciously) don’t mind if journalists lie to them.

One could say that “making stuff up” is an American tradition that began long before the 2016 and 2020 elections.

Writing for Harvard’s Nieman Foundation, Jon Grinspan described how a 19th-century news revolution sparked activists, influencers, disinformation, and the Civil War. As newspaper printing technology improved, American newspapers became more widely available, increasing from only a few printed newspapers in 1800 to 4,000 by 1860. As a result, literacy rates increased, and Grinspan said that many Americans became “news junkies” with strong political opinions:

In fact, the most divided period in the history of U.S. democracy — the mid-1800s — coincided with a sudden boom in new communications technologies, confrontational political influencers, widespread disinformation, and nasty fights over free speech. This media landscape helped bring about the Civil War.

Here are some additional resources about the history of fake news in the United States.

- Fake News? That’s a Very Old Story. – The Washington Post

- Fake News, Real News: History of Fake News – Middlesex College

- An Independence Day Salute to Our Founding Fathers of Fake News – Thom Fladung of Hennes Communications

Most Americans ignore or dismiss most political disinformation that they encounter on a daily basis, but that’s not the case for everyone. Ethical media professionals and civic-minded media consumers should feel a sense of duty to positively impact the U.S. media landscape through their media interactions.

In a TED talk about the future of media, Substack cofounder Hamish McKenzie said this:

The chaos of our current media moment cannot last. but then no one’s quite sure what the new landscape is going to ultimately bring. And that’s why our choices today matter so much. Every subscription, every share and every minute of our attention is a vote for the culture we want to flourish.

THE EVOLUTION OF MEDIA TECHNOLOGY

This OER text will emphasize that, when it comes to disruptive technology, media history repeats itself. Here is a media history question that may give you some perspective on that concept.

Creative Commons Image

The contraption in the picture above is a telegraph, used to send coded messages electronically beginning in the 1800s. If you are a history buff, you can read the History Channel’s explanation of “Morse Code & the Telegraph.”

Next comes a question about image manipulation.

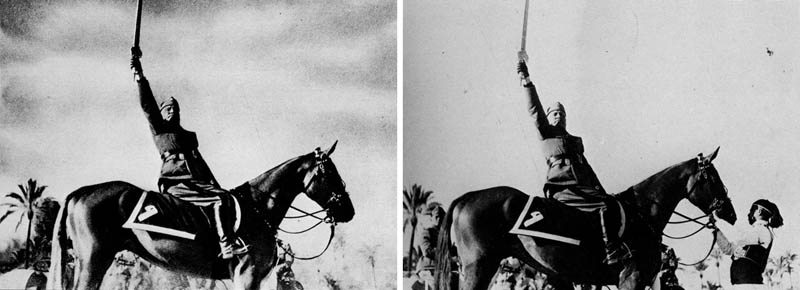

As an example, compare the two images below. In the 1940s manipulated photo on the left, it appears no one is holding the reins of a horse ridden by Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. In the original photo on the right, we see there actually was someone handling the horse while Mussolini posed.

Photoshop was not developed until the 1980s, and this is one of many famous examples of image manipulation that came before digital photography.

You can peruse lots of interesting image-manipulation case studies, starting with an 1860s example involving Abe Lincoln, in the following document from Georgia Tech University.

ARE WE SLIGHTLY ARROGANT?

Here’s an irony about personal perceptions of media literacy.

- Over 70% of surveyed college students said they have somewhat high or very high media literacy skills.

BUT - Only 32% rated the media literacy of their peers as somewhat high or very high.

Also, according to a Student Voice survey, over 60% said they are concerned about the spread of misinformation among their classmates.

Beyond college students, the irony likely reflects a larger psychological trend of individual Americans overvaluing their own media literacy skills while assuming that other people aren’t as media savvy.

OUR PERSONAL BIASES

Media researchers have consistently found that our biases affect our interpretation of the information we consume. According to an analysis published by Harvard’s Nieman Lab, a more recent trend is that “our evaluations of external reality are increasingly partisan” based on our political beliefs.

Despite widespread statistical data showing declines in most nationwide crimes since 2021, especially fewer violent crimes, most Americans in the first half of of the 2020s believed crime was steadily increasing. According to a Gallup survey, 90 percent of Republicans in 2024 said there was more crime in the United States than there was in the previous year, while only 29% of Democrats said there was more crime.

Likewise, despite statistical evidence that the national economy in 2024 was healthy and expanding, a majority of Americans, especially Republicans, believed the economy was in a recession. An analysis from the Brookings Institution said that “by most measures, consumer attitudes about the economy have been divorced from the underlying economic conditions.”

Surveys showed that Americans typically had a rosier view of crime in their own locations but still believed that the nation as a whole was becoming more dangerous. Similarly, the Nieman Lab analysis said that Americans often “feel quite good about their own financial situation, but they’re convinced the American economy writ large is in dire straits.”

We’ll learn more about a related concept, called hostile media phenomenon, in chapter 3.

MEDIA TECHNOLOGY IN THE 2020s

Here’s a poem about a special dog, adopted from an animal shelter, who is one of my best friends.

Harvey the Mutt, a dog of mixed breed,

With a wagging tail, and a heart full of need.

Though not a pedigree pup, you see,

His loyalty and love are pure and truly free.

He’ll be your companion, through thick and thin,

Harvey the Mutt, a true friend within.

You may be wondering why this poem appears in our OER text as part of this chapter. Here’s a flip card that may explain that.

Content-creation tools using artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT, are disruptive media technologies in the 2020s. If media history is a guide, we can predict that most people will adjust and adapt to the new technology. It will lead to the elimination of some jobs and the creation of others.

However, our media landscape will forever be changed, much like it was with the advent of the printing press, the telegraph, radio, movies, television and the internet.

IS ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE REALLY BULL*#*#?

You may be surprised to learn that there is an academic definition of the term bullshit based largely on the pioneering work of a Princeton professor, Harry Frankfurt, who wrote an influential book titled On Bullshit.

Three academicians at the University of Glasgow in Scotland applied Frankfurt’s principles to publish a research work titled “ChatGPT Is Bullshit.” They argued that, rather than hallucination, the more appropriate term to describe the output of large language models, such as ChatGPT, is bullshit. Here is part of their argument:

The problem here isn’t that large language models hallucinate, lie, or misrepresent the world in some way. It’s that they are not designed to represent the world at all; instead, they are designed to convey convincing lines of text.

In the audio below, one of the co-authors, Joe Slater explained the challenges of truth and verification related to text generated by large language models such as ChatGPT.

Audio: Truth and Verification

Slater also provided a brief warning about unintended plagiarism resulting from text generated by AI-generated text.

Audio: Unintended Plagiarism

As an addendum to the poem and audio above, you could read a Wired feature story titled “Anthropic’s Claude Is Good at Poetry — and Bullshitting,” which analyzed the reliability of the large-language model Claude. Anthropic, an AI safety and research company, built Claude. Chris Olah, who headed a research team for Anthropic, said he sees two extreme outcomes: “There’s a world where we successfully train models to not lie to us and a world where they become very, very strategic and good at not getting caught in lies.”

MORE CONCERNS ABOUT AI

The argument from the Scottish researchers above is one of many evolving viewpoints about AI-generated content, which likely will be both reviled and embraced by future media professionals and educators.

If you are a student in academic courses, I strongly recommend that you consult your instructor before using any AI tools to complete assigned work. This will help you avoid a breach of academic integrity.

Accuracy is frequently a concern. In a research study conducted by the startup company Vectara, AI chatbots invented information at least 3 percent of the time. In some situations, that number climbed as high as 27%.

More recently, research suggests that as artificial intelligence is getting more powerful, its hallucinations are getting worse. Amr Awadallah, an executive with Vectara, said that AI systems “will always hallucinate. That will never go away.”

A BBC study of representation of BBC News in AI content included these two statistical concerns:

- 19% of AI answers which cited BBC content introduced factual errors – incorrect factual statements, numbers and dates.

- 13% of the quotes sourced from BBC articles were either altered from the original source or not present in the article cited.

Also, consumers often cannot tell the difference between authentic online reviews and ones produced by AI. This contributes to a media landscape in which we become skeptical of everything we see. To combat AI-generated fake reviews, the Federal Trade Commission banned the sale or purchase of fake reviews and testimonials, saying they “pollute the marketplace and divert business away from honest competitors.”

The New York Times chronicled an extreme example of this chaotic landscape in an article titled “Let’s Rescue Book Lovers From This Online Hellscape.”

Internet sleuths figured out that an author named Cait Corrain, whose debut novel was scheduled for 2024, had created fake accounts on Goodreads in order to review-bomb other books — overwhelming them with negative one-star reviews. When confronted online, she concocted a fake online chat to divert blame to a nonexistent friend; when that hoax was uncovered, she confessed, citing a “complete psychological breakdown.

Finally, there are environmental concerns with the evolution of AI technologies. A summary from MIT said that “rapid development and deployment of powerful generative AI models comes with environmental consequences,” including increased electricity demand to run software and water consumption to cool hardware.

WHY YOU SHOULD EMBRACE AI (carefully)

On the other hand, many professionals already use AI tools to complete tedious tasks and sift through data, so it’s a good idea for you to experiment with AI tools now.

For example, there are a limited number of ways to phrase a brief promotional description of a typical apartment with two bedrooms and two bathrooms. As long as the advertising pitch for the apartment is accurate, readers may not care if it is generated by an AI tool.

Despite concerns about accuracy and ethics, future professionals can benefit from understanding how artificial intelligence is used to generate text, audio and visual content. Plus, the amount of hallucination (or bullshit) may decrease as AI products evolve.

QUIZ YOURSELF

Consumers face many challenges with judging the authenticity of online photos and videos. You can quiz yourself with the following interactive exercise from The New York Times:

Consumers face many challenges with judging the authenticity of online photos and videos. You can quiz yourself with the following interactive exercise from The New York Times:

And you can test your ability to identify AI-generated parts of images:

Finally, this quiz checks your skill in spotting AI-generated videos:

(The OER text includes content from The New York Times. If you are University of Arkansas student, you have free access to The New York Times through a confirmation link.)

If you missed several of the questions in the quizzes above, you’re not alone. Today broadcast an inside look at feel-good fake videos and the revenue they potentially generate.

TWO CLOSING JOKES (an experiment with ChatGPT)

One drizzly Friday in 2023, my collaborator on this textbook project, Alyssa Riley, found some online jokes to share with a few students who needed some comic relief. Here are two of the jokes:

JOKE 1 – What did the police officer say to his belly button?

You’re under-a-vest

JOKE 2 – How do you get a country girl’s attention?

a-tractor

As an informal experiment, Alyssa then asked ChatGPT (free version) to answer those two questions in the context of a joke.

ChatGPT provided a verbatim punch line on the first joke, meaning that the language used for Joke 1 was stored someplace that ChatGPT could locate and replicate.

ChatGPT’s response on the second joke, however, demonstrated how a large language model (LLM) can generate odd or unexpected content in ways we do not fully understand.

JOKE 2 – How do you get a country girl’s attention?

(ChatGPT Answer) Play a tune on your banjo and ask her if she wants to two-step with you under the stars, but make sure to bring a sweet tea and a pickup truck – because nothing says romance like a tailgate serenade!

I’ll admit this was just an amusing experiment with an AI tool. Consider, though, the broader implications when an AI tool generates a similarly random response in a query for specific medical or financial advice instead of the punchline to a joke.

TRUE or FALSE

The following questions highlight a few tidbits of information from the chapter. Use the forward button to advance through the questions.

SHORT OPENING REFLECTION

Write approximately 300 words summarizing changes in mass media technology that you’ve observed in your lifetime. In what ways do the media changes you’ve experienced relate to information and concepts mentioned in the opening chapter?

Include at least one paragraph about the concept of disinformation and the extent to which you previously knew that news content has been manipulated throughout U.S. history. Be sure you have listened to the assigned NPR audio about fake news, and incorporate support from that audio in your response.

Based on the “Quiz Yourself” section in this chapter, you may want to include brief commentary on how you rate your skills in identifying media content that has been manipulated. You can also discuss how often you encounter manipulated content in your daily media routines.

Over your lifetime, do you think changes in your media habits have led you to information that is more reliable or less reliable?

To follow journalistic style, you should write crisply with no more than three or four sentences per paragraph.