3 Traversing Our Mass Media Landscape

By Dave Bostwick

WE’RE ALL VULNERABLE

I want to give you a very personal example about my father. He read two newspapers every day, watched a local news broadcast every evening, and remained highly informed his entire life.

A few years before he died, media coverage of bed bugs spiked, and one morning he woke up with itchy ankles. He was convinced his house had been invaded by bed bugs, and thus began two years of expenditures on a variety of bed-bug eradication strategies, even though he lived alone with few visitors and there was never any physical evidence that bed bugs were in the house.

A few years before he died, media coverage of bed bugs spiked, and one morning he woke up with itchy ankles. He was convinced his house had been invaded by bed bugs, and thus began two years of expenditures on a variety of bed-bug eradication strategies, even though he lived alone with few visitors and there was never any physical evidence that bed bugs were in the house.

He didn’t suffer from dementia, but it became difficult to have a conversation with him to suggest that, in fact, there might not be any bed bugs in the house. His age may have had something to do with this, but I think our media landscape contributed to the problem as well.

By studying audience analytics, editors and advertisers at the time knew that bed bugs were a trending topic, so my father continued seeing and reading content about bed bugs, such as the following:

- National news articles about bed bug outbreaks in major cities, especially in hotels

- Local news stories that piggy-backed on the bed bug phenomenon

- Advertisements for products to combat bed bugs with sales pitches to make it seem like bed bugs are everywhere

To some extent, we’re all susceptible to media manipulation. Part of being media literate may be acknowledging that we’re not as invulnerable as we think we are.

And to be fair, as the screenshot below suggests, there are companies that spend ad money in a good-faith attempt to help consumers avoid problems such as bed bugs in the first place.

YOUR MEDIA LANDSCAPE

Can you think of an instance when social media posts, news coverage or advertisements caused personal fear or anxiety that you had not previously experienced?

MORE THAN ONE VIEWPOINT

The following introductory presentation outlines a few key points about the importance of finding multiple points of view.

Study the following presentation slides by using the forward button or clicking on sections of the control bar. To enlarge any interactive presentation in this book, click on the lower-right full-screen option (arrows).

If you were intrigued by the opening flip-card question and want to study more about how Americans define news, you can peruse the following research from the Pew Research Center.

- What Is News? – How Americans decide what ‘news’ means to them – and how it fits into their lives in the digital era

BROAD PERSPECTIVE

In a New York Times analysis, Shira Ovide wrote that “outrageous, bombastic and sometimes untrue things are more engaging than the truth.” That’s nothing new in the U.S. media landscape.

In the first chapter, you read about how some early American historical figures, such as Ben Franklin, concocted stories to gain political support. In future chapters, you’ll learn about sensationalized newspaper stories during the period of yellow journalism, and you’ll study how television quiz show scandals in the 1950s led some Americans to distrust what they saw on television.

For more modern perspectives, read content under the the following four tabs, keeping in mind that many of us are both media consumers and content creators, especially via social media.

QUICK CASE EXAMPLE

We’ll examine a specific social media post in the interactive presentation below.

Study the following presentation slides by using the forward button or clicking on sections of the control bar. To enlarge any interactive presentation in this book, click on the lower-right full-screen option (arrows).

The takeaway here is that when we see content that seems bombastic or extreme, especially on social media, we shouldn’t repeat that information verbatim unless we conduct our own verification.

TRUST AND NEWS AVAILABILITY

Many Americans say they want objective, facts-only news. They complain about seeing too much biased coverage. However, there is often a difference between what we say and what we do, especially when you consider that social media has overtaken television as Americans’ top news source.

For example, the Associated Press News and Reuters offer mostly staid, objective news content. Both outlets have loyal followers, but not huge audience shares.

Conversely, MSNBC on the political left and Fox News on the right have generally been successful and profitable in offering subjective viewpoints and commentary based on their audience preferences.

In addition, clickbait articles and ads seem ubiquitous online, mainly because they work. That’s the opposite of what many Americans say they want.

The outlook for objective news on the local level isn’t encouraging. A 2024 article from Harvard’s Nieman Lab reported that most Americans say local news is important, but they’re consuming less of it. A declining interest in news altogether is “most pronounced among younger Americans.”

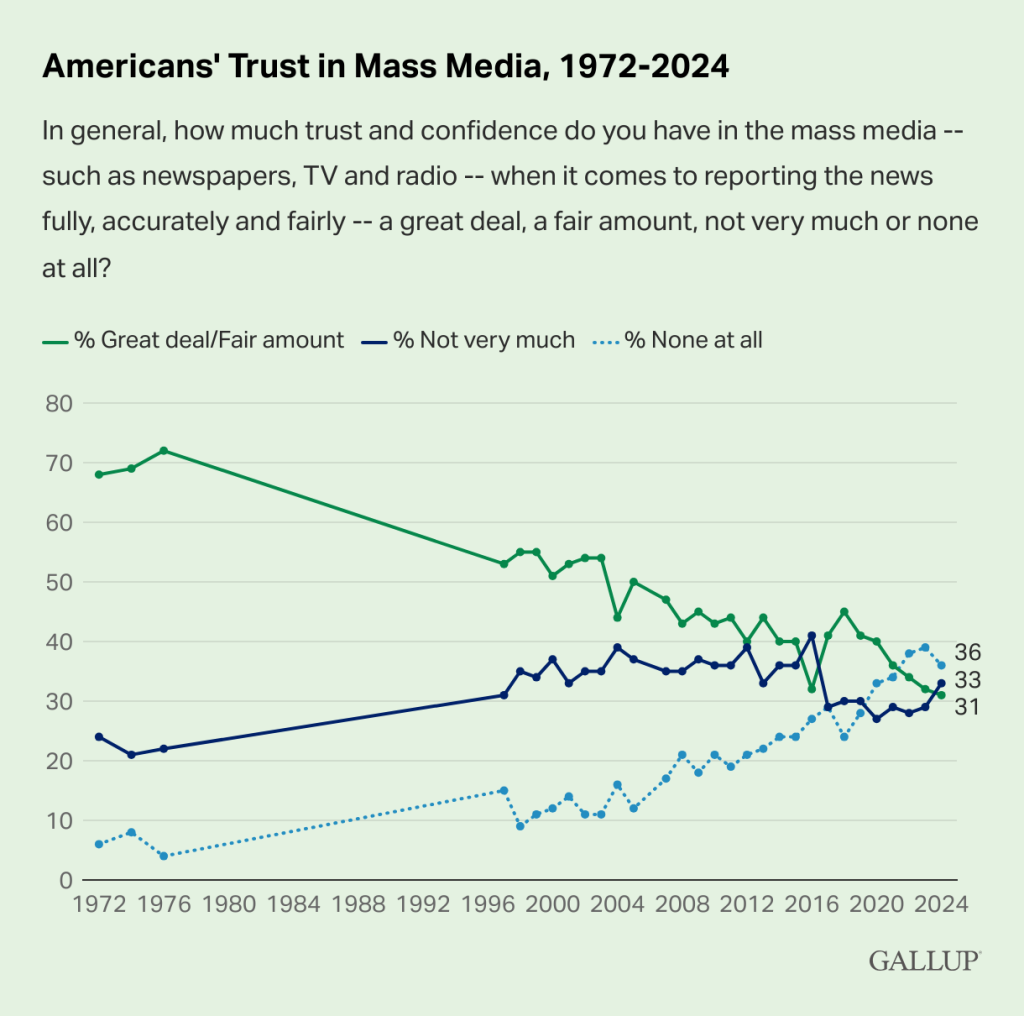

Furthermore, Americans’ trust in media is at an all-time low. In a 2024 Gallup poll, only 31% of Americans expressed a “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence in the media to report the news “fully, accurately and fairly,”

The chart below from Gallup illustrates the decline in media trust.

Due to declining audiences and diminishing trust, a 2024 New York Times analysis predicted the U.S. news business will become grimmer.

The pain is particularly pronounced at the community level. An average of five local newspapers are closing every two weeks, according to Northwestern University’s Medill School, with more than half of all American counties now so-called news deserts with limited access to news about their hometowns. Of 1,100 public radio stations and affiliates, only about one in five is producing local journalism.

A separate report from a non-profit group found that more than 1,000 U.S. counties — one out of three in the nation — do not have the equivalent of even one full-time local journalist. This impacts local citizens and may be a consideration for students interested in local journalism as a career.

FOREIGN INFLUENCE

Partly due to the the decrease in locally based U.S. news outlets, some foreign countries have built campaigns to fill the void. World leaders also have tried to influence public opinion through political commentary on social media and websites labeled as news.

As an example of foreign influence on American media content, consider a U.S. federal indictment filed just two months before the 2024 presidential election.

According to the indictment, some conservative U.S. social media influencers accepted money to post social media videos intended to influence the election and undermine U.S. support for Ukraine. The indictment said that RT, a Russian state media network, hired a company in the United States to arrange distribution of the videos.

According to the indictment, some conservative U.S. social media influencers accepted money to post social media videos intended to influence the election and undermine U.S. support for Ukraine. The indictment said that RT, a Russian state media network, hired a company in the United States to arrange distribution of the videos.

The indictment did not name the U.S. company. However, several U.S. news outlets identified Nashville-based Tenet Media as a company that RT employees used to hire influencers and manage video content.

According to the indictment, a goal of the videos was to amplify political divisions in the United States.

Wired magazine reported that at least five of Tenet’s media influencers, who were not accused of wrongdoing, “portrayed themselves as victims.” The influencers said they were not aware that they were indirectly being paid through RT.

WHAT ELSE IS DIFFERENT ABOUT TODAY’S MEDIA LANDSCAPE?

As artificial intelligence impacts our lives in ways we may not fully comprehend, it’s harder to define and categorize which daily media interactions count as part of the mass media landscape.

The following video from Vox emphasizes that we’re already using AI more than we realize. Appropriately enough, the video is sponsored by an AI platform.

Before the internet led to 24/7 connectivity and paved the way for social media and AI, most Americans only consumed media content through traditional outlets like newspapers, magazines, television, movies and radio.

Today, almost everyone contributes to the media landscape. We’re no longer just consumers; we’re also creators and contributors on social media and various interactive websites.

We have avenues to share photos with friends on Instagram or post an AI-generated deepfake image of Taylor Swift on X. We can share important safety updates to a community group on Facebook or create a counterfeit robo-call that impersonates a U.S. president.

What’s really different today is the firehose of content that washes over us each day and the increasing complexity in determining which content is authentic and truthful.

AN AI STATEMENT WITH IMPACT

Here’s a fascinating courtroom example that illustrates both the potential and the complexity of creating and interpreting impactful AI content.

Gabriel Paul Horcasitas fatally shot Christopher Pelkey at a red light in 2021. As part of a sentencing hearing, Pelkey’s sister created an AI-generated video to depict how her late brother likely would have addressed the courtroom before Horcasitas’ formal sentencing. According to an NPR report, Pelkey’s sister said that she “could hear Chris’ voice in my head and he’s like, ‘I forgive him.'”

In the video below, the AI-generated version of Christopher Pelkey speaks directly to his shooter: “It is a shame we encountered each other that day in those circumstances. In another life, we probably could have been friends. I believe in forgiveness and in God who forgives. I always have and I still do.”

POISON SCREENS

I opened the chapter with a personal example about my father. But it’s not just the elderly who can suffer negative consequences from our media ecosystem. Recent research suggests that teenagers are often negatively impacted, as you’ll see in the following presentation.

Study the following presentation slides by using the forward button or clicking on sections of the control bar. To enlarge any interactive presentation in this book, click on the lower-right full-screen option (arrows).

This is a theme you’ll see in future chapters as well. In June of 2024, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called for tobacco-style warning labels on social media platforms to advise parents about the potential risks for adolescents’ mental health.

Some states set up protocols for eliminating students’ access to social media during school hours, such as the “Bell to Bell No Cell” law in Arkansas. After the law took effect, one high school principal cited in an Axios report said students were “working together more, talking to each other and looking each other in the eyes.”

As another example, a Florida law that went into effect in 2025 prevents children under 14 from having social media accounts. Children who are 14 or 15 have to get parental consent to start an account.

And in September 2024, the Arkansas Attorney General filed a lawsuit accusing YouTube and Google of targeting minors with harmful content that can lead to clinical addiction.

However, social media experts are skeptical about how effective state laws can be in tackling a global problem.

Beyond U.S. borders. Australian legislators in 2024 passed a law that barred everyone under the age of 16 from social media, and in 2025 South Korean legislators approved a national ban on cell phones in school classrooms.

As an extreme example of the negative effects of social media on younger teenagers, a New York Times article detailed how junior high students in Pennsylvania used TikTok to impersonate their teachers and post lewd, racist and homophobic videos.

Of course, it’s not just teenagers who are negatively affected by social media usage. According to one economic research study, social media users perceive that social media has negative economic value and is often addictive rather than helpful. A summary of the research from Harvard’s Nieman Lab said, “The findings suggest social media is worth less to us than the zero we pay for it. That we would be better off without it.”

In a New York Times analysis of smartphone usage, some sources suggested we need to recalibrate our relationship with technology. It’s hard to differentiate between correlation and causation, but the analysis included this observation:

By many measures, American society has become angrier, more polarized and less healthy during the same period that smartphones have revolutionized daily life.

PERSPECTIVES ON MEDIA LITERACY

Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year for 2023 was authentic. According to a Merriam-Webster news release, the selection was “driven by stories and conversations about AI, celebrity culture, identity, and social media.” The 2022 Word of the Year was gaslighting, selected for its evolving role in the “age of misinformation—of ‘fake news,’ conspiracy theories, Twitter trolls, and deepfakes.”

And as comedian John Mulaney observed about online bots, “We spend most of our day telling them that we’re NOT a robot just to log on and look at our own stuff.”

Our media technology continues to impact our language usage, our daily routines, and our tools for finding reliable information.

Even media professionals don’t fully understand the increasingly complex landscape in which they work, especially related to AI-generated content. Nonetheless, this chapter should end with some perspectives about media literacy.

Study the following presentation slides by using the forward button or clicking on sections of the control bar. To enlarge any interactive presentation in this book, click on the lower-right full-screen option (arrows).

The presentation above should also come with a disclaimer. A research study widely publicized in 2024 concluded that asking people to “do the research” on fake news stories can make the stories seem more believable, not less. Algorithms and AI tools sometimes give people more of the same intentionally erroneous or misleading information that they are trying to fact-check.

You’ll have additional perspectives about media literacy in future chapters.

A BETTER SOCIETY THROUGH MEDIA

In The Death of Truth, Steven Brill explained why it is imperative for Americans to work collectively toward re-establishing trust in today’s media landscape.

Living together fruitfully and happily is about trust. Enough people must trust the same facts and trust each other to rely on facts for societies to make decisions based on those facts.

TRUE or FALSE

The following questions highlight a few tidbits of information from the chapter. Use the forward button to advance through the questions.

MEDIA DIARY ASSIGNMENT

Besides the information and links in our chapters thus far, an additional resource for this assignment can be the following statistical summaries:

- U.S. Media Consumption – Oberlo

THE TASK

Track your own interaction with mass media for three days, including radio, television, books, newspapers and magazines as well as your use of computers, tablets and smartphones as they relate to mass media consumption. Your digital consumption can include social media, websites and smartphone apps. Also, monitor how much of your media interaction involves news and information as opposed to entertainment.

- If you are mindlessly web surfing or checking Facebook, TikTok or Instagram, that counts.

- If you are typing a personal essay on your laptop or using your smartphone as a calculator for a math project, that does NOT count.

- If you are texting on your smartphone, that does NOT count unless you are sending a message to a very large group.

- If you are reading a book/magazine/newspaper (online or in print) either for pleasure or for a class assignment, that counts.

- Of course, if you are consuming any media for entertainment, that counts (including streaming video from outlets such as Netflix or YouTube).

You should record specific amounts of time spent and information about content consumption so that your written analysis can include actual data.

Also, discuss the types of advertisements that you see, and note any unexpected places where you see ads. As an example, you may play a video game that doesn’t seem to clearly fit this assignment. However, if the game includes ads, that would count.

RESPONSES

Write a short (approximately 400 to 500 words) paper summarizing the highlights of your findings. Include some specific data in your paper, and feel free to include a chart or graph.

Following are some recommended discussion points for your response:

- What patterns and habits did you find in your media usage? (include specific data, including news vs. entertainment)

- What benefits do you derive from media consumption?

- In what ways, if any, does your media consumption hinder your personal productivity?

- How do you think your media consumption affects your personal viewpoints?

- In what ways do your media and news consumption habits differ from the typical American consumer? (feel free to conduct additional research to answer this question)

- What observations can you make about advertising in your daily media consumption, and in what ways does advertising affect your media habits?

You can organize your submission with a short, engaging introduction followed by a Q&A format and a brief conclusion. In the conclusion, explain what you learned about yourself and the media you consume.