6 Media Law

By Dave Bostwick

Like many Americans, when I see a speed limit of 55 miles per hour on a long stretch of highway, I often drive a bit faster than that. I may be breaking the law at 60, but I do not feel ethically obligated to drive 55 or slower, especially when other cars whiz by me going much faster.

Like many Americans, when I see a speed limit of 55 miles per hour on a long stretch of highway, I often drive a bit faster than that. I may be breaking the law at 60, but I do not feel ethically obligated to drive 55 or slower, especially when other cars whiz by me going much faster.

On the other hand, if I were to drive 85 mph on that same highway, I would become anxious about endangering myself and others. Driving that fast would feel unethical and selfish to me.

Conversely, if a dire emergency arose and I needed to transport a friend or family member to a hospital immediately (no time for an ambulance), I might consider it an ethical imperative to exceed the speed limit by a wider margin, even though I would be breaking the law.

Our laws are often based on ethical behavior for an orderly society. However, my opening examples suggest that there can be differences between law and ethics.

Our legal systems are based on external rules to govern members of a society. Everyone is supposed to follow these rules or risk legal consequences, which may involve punishment.

On the other hand, our ethical codes are internal guidelines for morality and conduct. The guidelines often are not binding.

This chapter focuses primarily on media law, and then in the following chapter, we’ll spend more time studying media ethics.

YOUR MEDIA LANDSCAPE

Which of the following concepts do you support more?

Concept 1 – Americans would benefit from additional legal restrictions and legislative oversight of media content, especially if it helps prevent chaos and misinformation.

Concept 2 – Due to the importance of the First Amendment, restrictions on U.S. media content should be extremely limited, even if some content seems intentionally offensive or untrustworthy.

THE FOURTH ESTATE

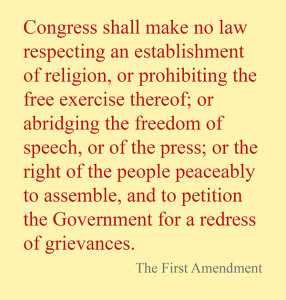

As you learned in a previous chapter, journalists have traditionally functioned as an unofficial fourth estate (or branch) of government, acting as a watchdog over government affairs. The First Amendment specifically says that Congress cannot make laws that abridge freedom of the press.

As you learned in a previous chapter, journalists have traditionally functioned as an unofficial fourth estate (or branch) of government, acting as a watchdog over government affairs. The First Amendment specifically says that Congress cannot make laws that abridge freedom of the press.

When you hear politicians complain about news media coverage, keep in mind that the Bill of Rights’ original purpose was to protect citizens’ rights. By design, the First Amendment creates a sometimes-adversarial relationship between government entities and journalists.

(MOSTLY) FREE SPEECH

The U.S. Bill of Rights guarantees freedom of speech and press, but there are a few exceptions for media content that is published or broadcast. The interactive presentation below explains some legal exceptions when we can’t just publish or broadcast anything we want.

Study the presentation slides by using the forward button or clicking on sections of the control bar. To enlarge any interactive presentation in this book, click on the lower-right full-screen option (arrows).

In the presentation above, the concept of libel is applied to people. However, in certain instances, a company can sue for libel as well. For example, in 2023, Fox News paid Dominion Voting Systems $787 million to settle a libel suit.

Dominion executives said the reputation of their company had been damaged because Fox News had broadcast false claims about the reliability of Dominion voting machines in the 2020 election.

According to a PBS summary of the settlement between Fox News and Dominion, the lawsuit records showed how Fox hosts and executives did not believe that Dominion machines were unreliable but aired false claims anyway.

Also, you can review the chapter 4 interactive presentation titled “Governmental Influence on U.S. Media” for case examples of how government offices and figures are sometimes involved in debates about censorship and free speech.

PLAGIARISM AND COPYRIGHT

For presentations, blogging and social media posts, many people assume it is OK to recycle any images that they find on the Internet. That’s not true, and it’s important for media professionals to understand legal and ethical implications for using images, text, audio or video from outside sources.

While some people make videos that include popular songs as background music, this is often a copyright violation as well.

The video below, from Adelphi University’s Mark Grabowski, provides a solid introduction to plagiarism and copyright.

FYI – As a courtesy, I emailed Mark Grabowski to let him know that I appreciated his videos and planned to embed them in some educational resources. However, I was not legally required to get permission. Content creators who post videos to YouTube have the option to make those videos publicly available so they can be embedded and viewed beyond YouTube’s website and mobile app. In effect, this automatically gives others permission to share those YouTube videos on other platforms (such as this OER text).

To review a few key takeaways about copyright, study the true-false questions on the following flip cards.

Click on Turn to see the answers, and use the forward button to advance through additional flip-card questions.

As an additional resource, the Student Press Law Center published a guide to copyright and fair use.

For historical context, it can help to understand that, more than a century after printing presses had begun churning out books in Europe, copyright was still not well defined. Media historian Jeff Jarvis wrote that “Shakespeare himself had limited control over the printing of his works. Often plays were published without authors’ names.”

THE NEXT FRONTIER

The next legal frontier in plagiarism and copyright likely will focus on content generated by artificial intelligence. Some content creators, both individuals and companies, want compensation if any AI tool scrapes copyrighted material to generate text responses, images, audio or video. For example, The New York Times filed a lawsuit for copyright infringement against OpenAI in an effort to protect the Times’ intellectual property. OpenAI released ChatGPT in 2022.

An NPR article noted that “if a federal judge finds that OpenAI illegally copied the Times‘ articles to train its AI model, the court could order the company to destroy ChatGPT’s dataset, forcing the company to recreate it using only work that it is authorized to use.”

On the other hand, OpenAI representatives can argue that ChatGPT’s reliance on newsworthy content (such as NY Times articles) should be considered fair use, in part because it broadly benefits the public.

Related legal cases extend beyond text. For example, Disney and NBCUniversal have sued Midjourney for copyright infringement in some of Midjourney’s AI-generate images. The lawsuit called Midjourney a “bottomless pit of plagiarism” and specifically mentioned characters from Marvel, DreamWorks, Pixar, and Disney, such as Buzz Lightyear, Shrek, Homer Simpson, Iron Man and Darth Vader.

The doctrine of fair use allows journalists and others to use small amounts of copyrighted material without collecting the copyright holder’s permission, mostly for public comment, news reporting, teaching, or research. However, any fair use of copyrighted material should not decrease the economic value of the original work.

Developing and enforcing uniform regulations for AI products will be especially challenging because of the many global conglomerates that dominate the industry, including Google and Microsoft.

And here’s an addendum to the financial and legal battles over AI data and news media content. While the New York Times’ lawsuit against OpenAI was still ongoing, Open AI signed a deal to bring news content from the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post to ChatGPT.

Meanwhile, the AI platform Perplexity announced it will license content from over 200 local Gannett publications and USA Today.

INSTANT MUSIC AND FAKE LISTENERS

For an example of media law’s complexity in the AI era, consider the case of Michael Smith, a North Carolina man who used AI tools to create what he called “instant music” that he credited to fake bands. He uploaded the music to popular streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music.

For an example of media law’s complexity in the AI era, consider the case of Michael Smith, a North Carolina man who used AI tools to create what he called “instant music” that he credited to fake bands. He uploaded the music to popular streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music.

Smith also created thousands of fake streaming accounts and then programmed computer bots to loop the fake songs through those accounts.

According to a description of the allegations in a press release from the U.S. Justice Department, Smith “fraudulently obtained more than $10 million in royalty payments through his scheme.”

The press release called this the “first criminal case involving artificially inflated music streaming.”

Beyond legal cases (for now), a Wired magazine article noted that “AI slop music is getting harder to avoid” as AI-generated music becomes more ubiquitous but authorship is less transparent.

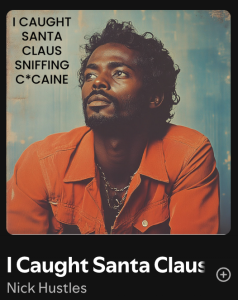

As an example, the article cited a song titled “I Caught Santa Claus Sniffing Cocaine.” On Spotify, the song is credited to Nick Hustles. Major news outlets have not yet reported on whether Santa Claus plans to file a libel lawsuit.

FINDING USABLE IMAGES

The Internet is full of copyrighted images that you should NOT use without permission, but there are also several online sites where you can find ready-to-use images.

The Internet is full of copyrighted images that you should NOT use without permission, but there are also several online sites where you can find ready-to-use images.

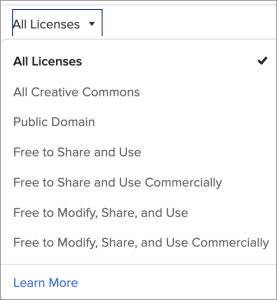

For example, DuckDuckGo features a simple search process for Creative Commons (CC0) images. Here’s the step-by-step process that I use:

- Enter a search term in DuckDuckGo.

- When the results appear, click on “Images” in the top list of options.

- A list of sub-options will appear. Go to the drop-down menu for “All Licenses” and select an appropriate license, such as “Free to Share and Use” (for non-commercial work) or “Public Domain.”

- From there, you should be able to click on links that give you access to image files and information on how to credit sources as needed. For some public domain images, you may not need to credit the source, although it’s always helpful to provide a link to the original image.

If you are partial to Google, just remember not to use a standard Google image search. Instead, you can enter a search term in Google’s Advanced Image Search. Before you conduct your search, scroll down the page to the drop-down options for usage rights. If you are not benefiting financially from use of the images, you can select “Creative Commons licenses.”

Many sites that host creative commons (CC0) images, such as Wikimedia, Wikipedia, Pixabay and Flickr, will provide guidance or copy-and-paste text for giving credit. Otherwise, make a good-faith effort to cite an owner and/or web address for any Creative Commons image that you use, and you should be OK.

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION

According to the U.S. government’s FOIA website, the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), established in 1967, gives ordinary citizens “the right to request access to records from any federal agency. It is often described as the law that keeps citizens in the know about their government.”

The following video from the U.S. Justice Department provides a brief overview of FOIA.

Individual states have their own freedom-of-information laws pertaining to state and local governments. For example, the Arkansas Freedom of Information Act is generally considered one of the country’s strongest in giving journalists and others access to public records and meetings.

It also was written to ensure that journalists and other citizens should be notified about public meetings, which must be held in public view. The Arkansas FOIA stipulates that “governing bodies may only enter into closed sessions for the purpose of considering employment, appointment, promotion, demotion, disciplining or resignation of an individual officer or employee.”

As a whole, freedom of information laws increase transparency by ensuring citizens can follow governmental decision-making processes and monitor how governmental bodies spend tax money.

CLOSING PERSPECTIVE

A key theme of this OER text is that media history often repeats itself. When radio surged in national popularity approximately one century ago, newspaper publishers sought legal remedies so that radio hosts couldn’t provide daily news updates merely by reading newspaper stories on air.

Similarly, many news organizations today are seeking legal remedies to protect their content from companies that develop tools for generating AI text, images and videos.

In an opinion article written for Harvard’s Nieman Foundation, Jeff Jarvis included the following analysis:

The real question at hand is whether artificial intelligence should have the same right that journalists and we all have: the right to read, the right to learn, the right to use information once known. If it is deprived of such rights, what might we lose?

FILL IN THE BLANKS

MEDIA LAW RESPONSE + ARTICLE SUMMARY

Part A – Short Response

Based on content and links in this chapter, respond to the following prompt.

Summarize some key information that was new to you or that contradicted ideas you previously assumed about media law. Feel free to share self-confessions about when you have not properly followed copyright guidelines in giving presentations or posting your own online content. (If you initially struggle with this response, review the linked CNN explanatory article with hypothetical examples: “The First Amendment doesn’t guarantee you the rights you think it does..”)

Your response in Part A should contain approximately three paragraphs with three tightly constructed sentences per paragraph.

Part B – Article Summary

Summarize a current-events article related to media law.

The New York Times, the Student Press Law Center and The Guardian provide separate categories for stories related to libel specifically and media law in general. The following are your links:

The New York Times (libel and slander)

The Guardian (media law)

Student Press Law Center (general news about media law as it applies to student media)

Note that not all of these stories describe U.S. cases.

At the beginning of your submission, provide the headline and link to your selected article/example. Then follow these guidelines for your explanatory text:

- Use short paragraphs in journalistic style of no more than three or four sentences per paragraph.

- Explain the major issues that are involved.

- Explain how your selected article/example connects with the explanatory content and videos in this chapter.

- Write approximately 150 words for Part B.

Additional Guidance for This Assignment

We’re in the midst of covering media law and media ethics, so it would be totally inappropriate to work unethically on this assignment.

In your writing, you should not copy and paste any external text, unless you use short snippets within quotation marks and clearly acknowledge the original source. For this assignment, the concept of fair use can apply because you are analyzing and commenting on a newsworthy topic.

You should not use any AI text generating tools such as ChatGPT, Perplexity or Google Gemini.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

If you are interested in a deeper dive into media law, here are a few starting points.

- The Law and Mass Media Messages – online texbook

- Defamation Law Made Simple Nolo.com Legal Resources

- Obscenity Law – Middle Tennessee State University

- The First Amendment doesn’t guarantee you the rights you think it does – CNN

And for an overview on invasion of privacy, you can take an online quiz from the Student Press Law Center.