17 Advertising

By Dave Bostwick

Revenue streams are embedded in much of the mass media we consume.

HBO, for example, relies primarily on viewers paying for access to its programming via paid subscriptions. On the other hand, the major U.S. broadcast television networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, Fox) generate revenue from advertisers instead of charging a direct subscription fee to viewers.

Movie theaters show a few advertisements before a feature film begins but primarily rely on patrons to pay for tickets before entering the theater. And, of course, movie theaters get some auxiliary revenue from food and drink sales.

This chapter focuses on the second revenue stream in the opening flip card: advertising.

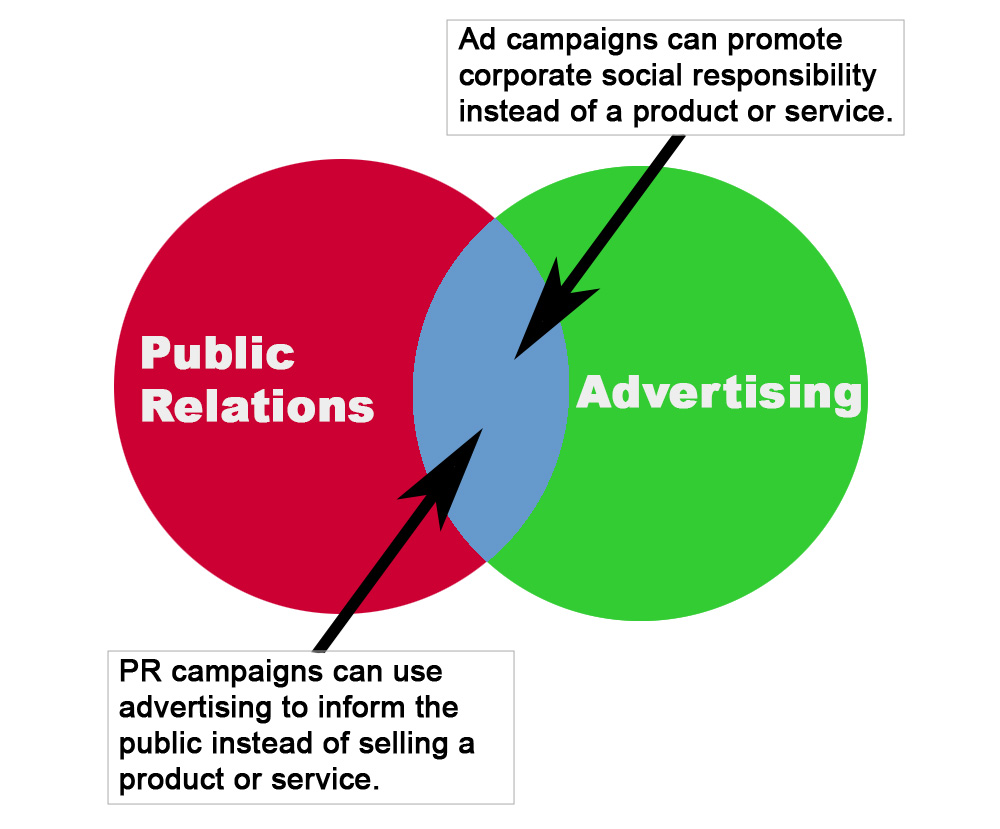

After studying public relations in the previous chapter, it may be helpful to see a simple visualization of how advertising and public relations are separate concepts but sometimes intersect.

Simply put, advertisers sometimes focus on PR goals instead of sales, and PR professionals sometimes use ads to promote goodwill and educate consumers.

YOUR MEDIA LANDSCAPE

- What kinds of ads are most likely to lead you to spend money on a product or service? Why? Where do you see or hear these ads?

- What kinds of ads annoy you, maybe to the point that you avoid them? Why? Where do you see or hear these ads?

ADS EVERYWHERE

It’s impossible to accurately calculate the number of ads we are exposed to each day, but one video about ads and brands estimated that number is between 4,000 and 10,000.

Marketing and advertising researchers have spent more than a century studying media stimuli that lead consumers to spend money on products and services. The following video offers a brief introductory overview of neuromarketing in advertising.

WORDS TO MAKE ADS MEMORABLE

Some catchy ad campaigns stick in our heads for a lifetime and can even affect our language usage. Here’s an oldie-but-goodie from Rice Krispies.

(As a side note, the letter K seems especially popular in branded spelling of product names, as in Rice Krispies, Kleenex, Kool-Aid, Krispy Kreme and Kit Kat.)

And here’s a more recent example of ad branding through product packaging and a slogan, courtesy of Liquid Death. The campaign also included a 2025 Super Bowl commercial.

Next, you can watch a television example of a song that many older Americans heard as children and can probably sing word-for-word (and letter-for-letter, in this case) for the rest of their lives.

Another older example helped audiences in the 1970s memorize the ingredients in a Big Mac.

Slogans and catchphrases – such as “Red Bull gives you wings” or “Like a good neighbor, State Farm is there” – are still a key strategy in many of today’s advertising campaigns. They typically sell products and services, but they can also create branding imagery for non-profits and even the military, as in the catchphrase for the U.S. Marine Corps: “The Few. The Proud. The Marines.”

Now, let’s have some fun testing your abilities to identify ad slogans. Many of the slogans in the brief interactive quiz below are more recent than the examples above.

Even news media outlets can promote themselves through slogans. Here are two examples.

- The New York Times: All the news that’s fit to print

- The Washington Post: Democracy dies in darkness

And if you want more slogans and related commentary, here are three links to explore.

- 30 Companies with Famous Brand Slogans & Taglines – Adobe

- 21 Unforgettable Advertising Slogans (with Takeaway Tips!) – Wordstream

- The 50 Best Slogans of All Time – Something Great

SLIGHTLY CRINGEWORTHY (by today’s standards)

As we learned in a previous chapter, early U.S. television shows were often sponsored and produced by a single company. As programming evolved beyond the quiz show scandals of the 1950s, however, the major television networks (ABC, CBS and NBC) began producing more of their own entertainment content and sold advertising spots for 30 or 60 seconds.

Admittedly, some of the 1950s ads in the following video are cringeworthy or haven’t aged well, but they’ll give you a sense of early American TV advertising.

Note that these ads were product-specific, and the audience had fewer options to avoid or ignore an ad. They were made in an era when most households had only one television and, of course, there were no smartphones, which meant less competition for a viewer’s attention.

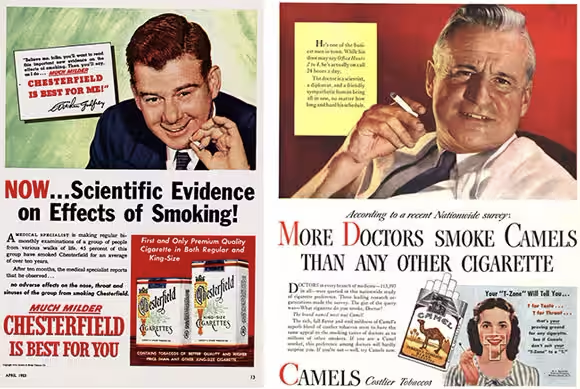

Beyond television, some cigarette ads in magazines from the mid-20th century may seem strange by today’s standards. Below are two examples.

As you learned in a previous chapter, cigarette ads haven’t appeared on U.S. television stations since 1971, when the FCC banned them on public airwaves.

SUPER BOWL ADVERTISING

According to a statistical compilation from USA Today, a 30-second slot during the Super Bowl I broadcast in 1967 would have cost an advertiser $37,500. Fast forward to 2025, and a 30-second ad cost as much as $8 million. Also, 2025’s Super Bowl LIX was the most-watched American telecast ever.

Between 1967 and the 1990s, the Super Bowl evolved to become the most high-profile advertising event of each year in the United States. As media content has become more specialized, the Super Bowl is perhaps the only time each year when more than 100 million Americans are watching the same thing at the same time.

One of the most historically significant Super Bowl ads came in 1984. An Apple Macintosh ad produced by Ridley Scott (the director of Blade Runner) alluded to George Orwell’s novel 1984, which was a warning against totalitarianism. Apple was hinting at the totalitarianism that IBM had developed in the computer tech industry at that time. The ad below, which is a stark contrast to the 1950s ad strategies you saw earlier in this chapter, is often considered the beginning of fully produced storytelling in TV ads.

Nationally, Apple’s 1984 ad was broadcast only once, during the Super Bowl, at a cost of $1 million. The ad cost almost $1 million to produce as well. A 2016 documentary video from NFL Films chronicled the impact of the 1984 Apple ad. Long before Nike’s Just Do It campaign, the Apple 1984 ad prioritized selling a brand’s image instead of detailing the features of a specific product. The new Macintosh computer itself did not even appear in the ad.

Fast forward 50 years, and the creative industry had a completely different reaction to an Apple ad titled “Crush!” to promote the iPad Pro. An Apple marketing executive apologized for imagery in the 2024 ad, which suggested to some viewers that Apple’s new embrace of AI tools could crush current creative processes.

ADVERTISING APPEALS

Some advertising analysts cite 20-or-more kinds of strategic appeals to consumers. For simplification in this brief chapter, though, we’ll boil those down to two broad categories.

- Emotional appeal

- Rational appeal

As the name suggests, ads using emotional appeals attempt to evoke strong emotions from the audience. These ads may rely on appeals to a consumer’s moral principles, personal aspirations, hidden fears, or sense of humor.

Emotional Appeal

An example of an emotional appeal would be ads using the Subaru slogan “Dog Tested. Dog Approved.”

And this 2019 example from SimpliSafe shows how fear can be used as an emotional appeal in an ad.

More recently, as advertisers explore the potential of AI content, Coca-Cola produced an AI-generated holiday ad that relied on emotional appeal.

Rational Appeal

Ads based on rational appeal focus more on logical reasons a consumer should consider purchasing a product or service, and they can include specific details for support. Following are two examples of rational appeal.

DECEPTION, DATA, GREENWASHING AND WEASEL WORDS

Of course, as with almost all aspects of U.S. media, portions of the advertising industry are occasionally deceptive or unethical. A study from Juniper Research showed that 22% of online ad spending worldwide in 2023 was lost to fraud, which totaled an estimated $84 billion. That number was projected to increase to $170 billion by 2028.

Also, online ads create ethical concerns about data privacy for users. Simply put, advertisers and tech companies aren’t always transparent about the ways in which they collect data to deliver targeted ads to users. For example, Wired magazine reported that “while private modes in web browsers prevent some data from being stored on your device, they don’t prevent tracking by websites or internet service providers.”

As another example, in early 2025 Apple Computer agreed to pay $95 million to settle a lengthy lawsuit involving the Siri voice assistant. The lawsuit alleged that “Apple shared some of the conversations that Siri secretly recorded with advertisers looking to connect with consumers who were more likely to buy their products and services.”

As another example, in early 2025 Apple Computer agreed to pay $95 million to settle a lengthy lawsuit involving the Siri voice assistant. The lawsuit alleged that “Apple shared some of the conversations that Siri secretly recorded with advertisers looking to connect with consumers who were more likely to buy their products and services.”

Claims within ads themselves are sometimes deceptive as well. As a 21st-century example, some corporations like to advertise that they are eco-friendly, or green.

Truth in Advertising explained that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has declined to define the terms “sustainable” and “organic” in advertising. As a result, companies can use those terms in product packaging and advertising with minimal fear of legal consequences.

The term greenwashing now refers to companies that make eco-friendly claims about their products and services even though the environmental evidence in the ads is misleading or unclear. Greenwashed ads for cleaning and beauty products have been more common in the past decade.

An essay from the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas suggested that “corporations should care about their environmental footprint, but some rely on greenwashing rather than genuine solutions for addressing the climate crisis, which can also make it difficult for the public to trust the companies that are seemingly keeping their promises to work toward greener business practices.”

And advertisers have historically used weasel words to make product claims that can’t be proven. For example, Papa John’s has used this ad slogan: “Better Ingredients. Better Pizza.” Logically, the slogan merely suggests that better ingredients lead to better pizza. We infer that Papa John’s uses better ingredients, but the word “better” is a matter of opinion and cannot be proven on a factual basis.

And advertisers have historically used weasel words to make product claims that can’t be proven. For example, Papa John’s has used this ad slogan: “Better Ingredients. Better Pizza.” Logically, the slogan merely suggests that better ingredients lead to better pizza. We infer that Papa John’s uses better ingredients, but the word “better” is a matter of opinion and cannot be proven on a factual basis.

The question in this case: “Better than what?”

AN AD IN OUTER SPACE (Product Placement and Sponsored Content)

In 2000 Pizza Hut paid $1 million for its logo to be placed on a Russian rocket that was sending supplies to the International Space Station. The company also sent a pizza into space for astronauts to cook and eat.

Randy Gier, Pizza Hut’s chief marketing officer at the time, said, “From this day forward, Pizza Hut pizza will go down in history as the world’s first pizza to be delivered to and eaten in space.”

This was a high-profile example of product placement, a strategy by which ads are embedded within media content instead of appearing or being broadcast separately. As a similar example, in 2024 an inflatable green dragon was temporarily attached to the Empire State Building as a promotion for HBO’s House of the Dragon, which prompted publicity from outlets such as NBC’s Today Show.

A simple example would be when you see a character in a movie or TV show drink a specific brand of soda or beer. A company may have paid for that product placement. As another example, Macintosh computers appeared in Mission Impossible movies, and Apple paid for that product placement.

Occasionally, a movie or show mocks product placement in an entertaining manner so that the audience is aware of product placement but still enjoys it. The 1992 movie Wayne’s World debuted at a time when U.S. audiences were becoming more aware of product placement in television shows and movies, and the following clip turned that into a parody.

As another example, the 2006 movie Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby relied heavily on product placement for humor while also mocking public service announcements, as seen in one of the movie’s bonus features.

The New York Times published “Anatomy of a Product Placement” to help readers understand the concept. An industry argument in favor of product placement is that many people no longer pay attention to traditional ads.

Product placement is categorized as one type of native advertising. Another type of native advertising appears in online and print publications when a company or organization pays for story content that resembles news or feature stories. This is often called sponsored content.

For example, The Washington Post’s Creative Group provides sponsored content opportunities for advertisers who believe they will benefit from paid articles and videos that look like news. One article from the Creative Group, titled “Time to Tailgate,” is sponsored by the supermarket chain Safeway. A small label at the top of the web page said “Sponsor Content by Safeway,” which is intended to provide transparency that the article can also be considered a paid advertisement.

As another example, the Dallas Morning News markets sponsored content opportunities to advertisers. One article explained how primary care doctors are a critical link to better health for seniors. The article is labeled as a sponsored post. Readers who scroll to the bottom of the web page can learn that the article’s author, Dr. Robert Zorowitz, is regional vice president of health services for Humana, a company that sells Medicare plans and health insurance coverage.

Another example, titled “Young Alumni Pay It Forward With Co-branded Coffee,” appeared on the Inside Higher Ed website. In small print under the byline, close readers may see “Content sponsored and provided by NC State University.” However, the article’s content is written much like a news story, especially in the use of sources and attributions.

A CULTURAL SHIFT

One Guardian article cited 2025 as a landmark year worldwide when social media creators overtook traditional media in advertising revenue, marking a “huge cultural shift” in the ad industry.

An analysis found that ad revenue from user-generated material – such as videos, podcasts and social media posts by individual creators – eclipsed revenue from professional media produced by TV networks, movie theaters and news companies.

The article acknowledged that the distinction between user-generated content and professional production can be blurry because some content creators use high-quality production techniques and tools.

PEACE, LITTLE GIRL

As a reminder about the impact of advertising on American society, we’ll close this chapter with an ad that some historians consider the most effective political commercial ever. It aired as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s successful 1964 campaign against Barry Goldwater, and it drips with emotional appeal to create fears about what might happen if voters pick the wrong candidate. Formally titled “Peace, Little Girl,” it was informally known as the “Daisy” ad.

FILL IN THE BLANKS

ADVERTISING IMPACT ASSIGNMENT

The ultimate goal of most advertising is to convince you to spend your money for a product or service. Think of a specific instance when you saw or heard an advertisement that enticed you to purchase something.

What sparked your initial interest? What aspects of the ad motivated you? In what ways did the ad fit appeals or strategies discussed in this chapter, especially concerning rational or emotional appeal?

Write approximately five journalistic paragraphs (approximately three sentences per paragraph) with specific details about the ad and its effective components as well as the eventual outcome of your purchase.