15 Internet

By Dave Bostwick

A little less than a decade ago, I taught a lesson about web searches to a group of graduating high school seniors who were using their own smartphones to experiment in class. I wanted to show them that Google search results often varied depending on data that Google had collected about individual users (and this is true for many platforms beyond Google).

At one point, I asked students to type their school mascot for a Google search. Several students attended a school with the panthers as their mascot, so they did a one-word search for panthers. The results were fascinating.

At one point, I asked students to type their school mascot for a Google search. Several students attended a school with the panthers as their mascot, so they did a one-word search for panthers. The results were fascinating.

Some students saw a Wikipedia entry for panthers (the animals) at the top of their search results. Some students’ results included links related to the NFL’s Carolina Panthers. One young woman who was active in cheerleading saw several web pages about “Panther Cheerleaders” on her page-one search results.

At the top of one Black student’s search was a link to information about the Black Panther political party, which gained prominence while advocating for Black rights in the 1960s. This student had never heard of the Black Panthers until that day in my class.

Keep in mind this was a few years before the Marvel movie The Black Panther, and the search results would no doubt yield different results today.

Nonetheless, this incident helps me establish my opening point for this chapter. The internet has evolved to make our mass media consumption customized and personalized. We peruse popular media platforms to locate content that algorithms suggest to us. On the other hand, the internet can create partitions among Americans based on their interests and beliefs.

It’s a trend that’s not likely to end soon. During the 2024 World Economic Forum, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said future AI tools will give different responses to users based on their locations and opinions. Altman, who is the founder of ChatGPT, added, “That’s going to make a lot of people uncomfortable.”

YOUR MEDIA LANDSCAPE

Can you think of personal examples when you sensed that a media platform gave you extremely personalized content based on your past media usage? To what extent does it concern you?

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

As we’ve studied in previous chapters, radio, magazines and television all evolved to become more specialized. One could argue that the internet has taken us from specialization to personalization because much of the internet content we see is based on our personal information and data.

The internet is a broad concept, and we could cover several chapters about connectivity and terminology. Instead, though, we’ll devote this one chapter to a basic understanding of the following:

- Brief history of the internet’s birth and evolution

- General idea of how the internet works

- Ethical and psychological concerns for society

Thanks to the internet, we have streaming video, so parts of this chapter will rely on Google’s YouTube to deliver key perspectives.

IN THE BEGINNING

I’m sure the pioneers of the World Wide Web did not envision that one day Americans would get news updates through a vaping device.

With that in mind, let’s start with a brief explanatory history video, courtesy of Interesting Engineering. Making it perhaps appropriate for this chapter, the video has a snappy, informal and slightly snarky style with animated graphics, as opposed to a more polished TV or movie documentary format.

One takeaway from the video: The internet is an open-ended technology that began as a means for researchers to share information securely and more efficiently. Much like radio, the internet did not begin as a medium for entertainment.

THAT’S THE INTERNET

The internet has rapidly evolved to become an essential part of Americans’ lives for job applications, education and daily communication.

A simple analogy may help you understand how domains work. Smartphone users often have people’s phone numbers saved on their devices. As a result, we often don’t need to type a phone number to make a call or send a text. Within our contact lists and other online platforms, names have already been connected to phone numbers and user devices.

Likewise, you don’t have to type a bunch of numbers to visit a website, even though, behind the scenes, a web server is connectable through a set of numbers (similar to a phone number). For example, when you type espn.com in your web browser address bar or click on a text link that says espn.com, you are automatically directed to ESPN’s web server, and there’s no need to memorize or input numbers.

Below is a short animated video from Blaster Technology that explains how the internet works. It includes a brief overview of how DNS technology resembles an old-fashioned phone book by associating an IP address with a lettered address (such as google.com).

You can also watch a longer, fully produced video from Vox titled “How Does the Internet Work? Glad You Asked.” Here are a few key quotes from the Vox video:

- “The cloud is a marketing term.” In fact, the internet is also a physical space that includes undersea cables, wires, hubs and routers.

- “At its most basic, a cell phone is a radio.” Binary information [ones and zeros] is sent through a router instead of a radio receiver.

- “There are lots of people that still don’t have reliable internet access.” Although internet access is a daily necessity for many Americans, it’s more of a luxury in some other countries.

THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

Much of this chapter will focus on ethical and psychological issues related to the internet. We’ll start with the digital divide.

Americans who can afford smartphones, tablets and computers typically have no problems staying informed. That is not the case for some low-income Americans, especially after the federal Affordable Connectivity Program expired in 2024.

The State of Local News Project at Northwestern University suggested that wealthier, urban Americans have access to more local news. Previous research also showed that a reliable internet connection was essential for many Americans during the pandemic, but not everyone could afford it.

As more of our daily media content becomes digital, including textbooks and government documents, a primary concern is that Americans who can’t afford high-speed internet access and smart devices will be at an informational disadvantage compared to wealthier Americans.

Furthermore, artificial intelligence has created a global digital divide, “fracturing the world between nations with the computing power for building cutting-edge A.I. systems and those without,” according to a New York Times interactive analysis. Data shows that American and Chinese companies operate more than 90 percent of data centers used for AI work worldwide.

POPULARITY vs. QUALITY

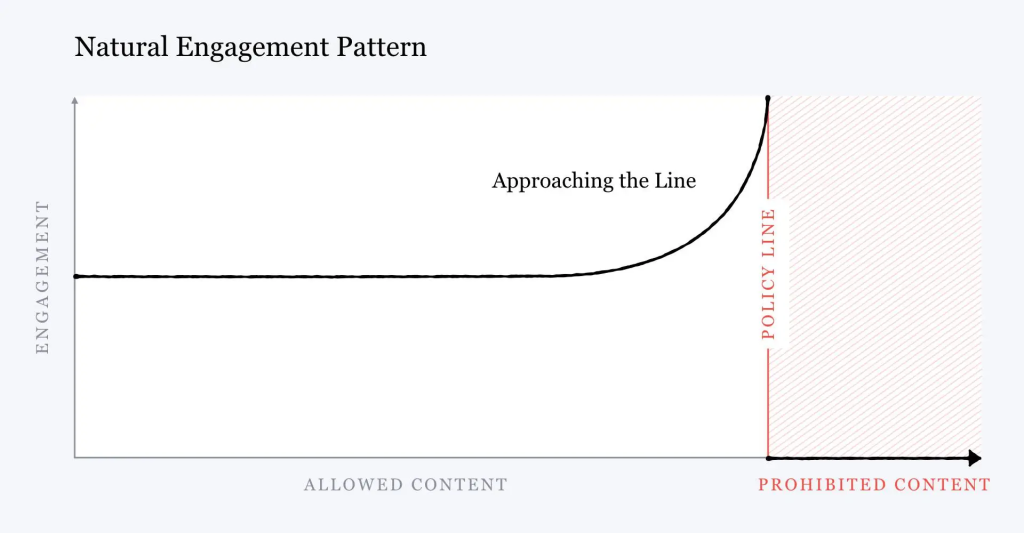

An MIT Technology Review article about how Facebook got addicted to spreading misinformation included the following chart based on information that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg shared in 2018.

The chart illustrates why it can be so difficult for social media platforms and websites to regulate users’ posts and minimize harm. The most popular content is often the closest to violating community standards. Social media and search algorithms tend to reward popularity. Consumers may say they dislike controversial posts and disinformation, but many of them are still lured by clickbait headlines and thus view misleading information or hate speech.

The New York Times’ Shira Ovide made an observation about Zuckerberg’s chart that seems pertinent to this chapter:

… no matter where Facebook drew the line at activity that went too far — dangerous lies, bullying, calls for violence, sexually suggestive photos — people tended to post material that went right up to the line. And they did that because, again, people found it engaging.

Writing for Gateway Journalism Review, William H. Freivogel had a related observation about social media in general:

Content creators are paid more by advertisers when posts go viral, regardless of their truth, so creators are incentivized to produce and amplify eye-catching content. False claims often are more eye-catching than truthful ones, studies have shown.

ONLINE CHILD SAFETY

In the past decade, social media executives have frequently been accused of ignoring the potential dangers for children who use social media platforms, including psychological damage, addiction and sexploitation. A New York Times article cited government documents showing that Meta rejected efforts to improve children’s safety.

In 2024, U.S. senators questioned executives from five companies – Meta, TikTok, X, Snap and Discord – about online child safety. A few senators even compared social media companies to cigarette makers. The most dramatic moment came when Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley spoke to Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg (and remember from a previous chapter that Facebook is part of the Meta conglomerate).

As an addendum, Meta agreed to pay President Donald Trump $25 million in 2025 to settle a lawsuit that Trump filed in 2021 after his Facebook and Instagram accounts were suspended.

Despite the drama in the video clip above, U.S. senators and representatives have struggled over the years to pass meaningful legislation to protect children online, set rules for appropriate content, and safeguard all users’ data. This has allowed social media platforms to operate with minimal federal regulations, although a few states have passed their own laws.

A related age-verification concern is that children and parents have to provide additional private information to social media companies and then trust that those companies will protect the data in the future.

For example, in 2023, Arkansas passed the Social Media Safety Act, which required age verification for social media usage and imposed penalties on companies that retain user data illegally and do not verify users’ ages. However, legal challenges, financed by social media companies and based partly on free speech rights, initially blocked the Arkansas law’s implementation.

Similarly, the U.S. Congress in 2024 passed a national ban or forced sale of TikTok. However, President Donald Trump extended the ban’s deadline multiple times amid a continued push to allow TikTok to remain available in the United States through joint ownership that includes U.S. companies.

IF YOU AREN’T THE CUSTOMER, YOU’RE THE PRODUCT

When we use social media, search engines and websites, we typically allow companies to collect data about our internet usage, such as sites we visit and items we search for. As a trade-off for much of our online content being free, we see lots of ads that can be based on the data that companies have collected about us.

You can say, then, that each American internet user is a product that can be sold to advertisers. In The Death of Truth, Steven Brill wrote that “the publisher and the publisher’s content are not the product. The product is you – the person whose data has been harvested so exquisitely that you are the advertiser’s target.”

Below is a partial screenshot of Privacy Badger, a browser extension I sometimes use to see hidden trackers that monitor my web browsing activity on various sites. The screenshot shows that, in this case, there were 46 potential trackers connected to a single web page that I visited.

As the Privacy Badger screenshot illustrates, trackers want to invisibly send information about our internet usage to advertisers and data brokers.

Online tracking isn’t always a bad thing, though. Here’s a kinder explanation from the All About Cookies website:

When you visit a website, it gives your browser a cookie to store in a cookie file that’s placed in your browser’s folder on your hard drive. The next time you visit the same website, the browser will give back the cookie to identify you. Then the website loads with a personalized experience.

Online tracking and cookies can help advertisers and public relations professionals measure effectiveness. For example, here are two website addresses that will in theory take readers to the same New York Times article.

ADDRESS 1 – https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/09/magazine/movies-theaters-streaming.html?campaign_id=9&emc=edit_nn_20240127&instance_id=113638&nl=the-morning®i_id=96912916&segment_id=156565&te=1&user_id=3544579ce1fb22c0827e722878b6f520

ADDRESS 2 – https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/09/magazine/movies-theaters-streaming.html

Why is the first address longer? The first address enables tracking. After the letters html, the first address is coded so that media trackers can collect data about how many people click on the link (which was originally embedded in an email newsletter) and where individual visitors go on the website after they click on the link. (Note: For privacy concerns, I altered a few numbers and letters in the user_id of the first address before publishing this chapter.)

PRIVATE FOR NOW (but maybe not forever)

A good case example for data privacy and consumers becoming products is 23andMe, a biotechnology company that offers genetic testing. Customers can provide a saliva sample, which is then analyzed to deliver personalized information about ancestry and health.

When 23andMe declared bankruptcy in 2025, it led to headlines about users whose genetic data was suddenly at risk. As a hypothetical scenario, 23andme’s immense trove of user data could be a valuable asset for companies that use targeted online advertising to promote health-related products and services. When they initially provided a saliva sample to 23andMe, most users probably did not consider any that their DNA data could become part of a data sets used for targeted-ad campaigns.

Beyond 23andMe, a larger question surfaced about what happens to any of our personal online data (including on social media) when companies collapse and we potentially lose control of our private information, which may even include location tracking.

POPULARITY CONTEST

We’ll wrap up this chapter with a video from Global Stats charting the most popular worldwide websites from 1993 to 2024. The video data is based on total monthly visits.

Consider how valuable it can be for a platform to gain users’ loyalty as their initial landing spot for online interactions. In the video above, the top slot shifted from America Online (AOL.com) to Yahoo to Google as the Internet moved from mostly human-curated content in the heyday of Yahoo to algorithms beginning with Google. That trend will likely continue so that we’ll see some embedded advertising in AI-generated search results.

Although the video shows lots of chart movement until 2012, Google then claimed the top spot for the remainder of the decade and beyond, while Facebook and YouTube battled for the second and third positions and all other platforms lagged far behind.

That doesn’t mean Google will remain entrenched at the top. For example, in 2024 OpenAI launched a prototype of SearchGPT as an alternative to Google’s linked search results.

NOTE: Due to the range of screen sizes (computers, tablets, smartphones) and platforms (websites, mobile apps), metrics used to gauge online traffic across multiple years are imprecise. The video above is merely intended to illustrate broad trends.

CLOSING PERSPECTIVE

If you are a prisoner of the moment, you may think that most mass media content was reliable back in the good old days before the internet ruined everything with fake news. As we’ve studied several times in this OER text, that’s an oversimplification. Here’s an additional perspective from The Gutenberg Parenthesis by Jeff Jarvis:

But it is important to recognize that many of the problems attributed to the internet are ultimately human problems, our failings. We bring to the net a long unbroken history of racism, misogyny, mistrust, and fear. The net did not suddenly teach us to hate. Turn off the internet tomorrow and the hate will still burn.

On the other hand, the internet gave more people a means to express their ideas and feelings. It has even given some of us hope that, collectively, we can improve the world through our evolving media tools.

FILL IN THE BLANKS

THE INTERNET’S IMPACT ON READING AND VIEWING – LIVING HISTORY

Several of our chapters have included stories about the the disruptive impact of the internet on traditional media platforms. Now it’s your turn to collect some living history about the internet.

The instructions are similar to a previous interview assignment about music and culture, except this time you are covering media evolution outside of music.

Interview someone whose lifetime has spanned a broad spectrum of changes in media consumption habits. Age 45 is probably a minimum for this assignment.

In most journalism settings, it is not appropriate to interview family members and friends, but for this assignment it is OK. You should not, however, interview parents or immediate guardians.

Visit with your interviewee about how their use of internet-connected media devices has evolved over the past decades. Ask questions about how they think the internet has changed their reading and viewing habits:

- Newspapers

- Books

- Magazines

- Movies

- Television

- Advertisements

Discuss the ways they think internet connectivity has changed American culture for better and for worse, including websites, social media and smartphones.

Summarize the highlights and key takeaways from your interview in a short narrative of approximately five paragraphs, with three or four sentences per paragraph.

Your summary does not necessarily need to mention all items in the bullet list above, but share the most interesting information that you gleaned from the interview.

Reminder — Do NOT use large-language models such as ChatGPT or other AI tools to generate content for this assignment.