Chapter 8: Racial & Ethnic Inequality

Chapter 8 Learning Objectives

- Describe the targets of nineteenth-century mob violence in U.S. cities.

- Discuss why the familiar saying “The more things change, the more they stay the same” applies to the history of race and ethnicity in the United States.

- Critique the biological concept of race.

- Discuss why race is a social construction.

- Explain why ethnic heritages have both good and bad consequences.

- Describe any two manifestations of racial and ethnic inequality in the United States.

- Explain how and why racial inequality takes a hidden toll on people of color.

- Provide two examples of white privilege.

- Understand cultural explanations for racial and ethnic inequality.

- Describe structural explanations for racial and ethnic inequality.

- Summary of the debate over affirmative action.

- Describe any three policies or practices that could reduce racial and ethnic inequality in the United States.

Introduction

Social Problems in the News

“Anger, Shock over Cross Burning in Calif. Community,” the headline said. This cross burning took place next to a black woman’s home in Arroyo Grande, California, a small, wealthy town about 170 miles northwest of Los Angeles. The eleven-foot cross had recently been stolen from a nearby church.

This hate crime shocked residents and led a group of local ministers to issue a public statement that said in part, “Burning crosses, swastikas on synagogue walls, hateful words on mosque doors are not pranks. They are hate crimes meant to frighten and intimidate.” The head of the group added, “We live in a beautiful area, but it’s only beautiful if every single person feels safe conducting their lives and living here.”

Four people were arrested four months later for allegedly burning the cross and charged with arson, hate crime, terrorism, and conspiracy. Arroyo Grande’s mayor applauded the arrests and said in a statement, “Despite the fact that our city was shaken by this crime, it did provide an opportunity for us to become better educated on matters relating to diversity.”

Sources: (Jablon, 2011; Lerner, 2011; Mann, 2011)

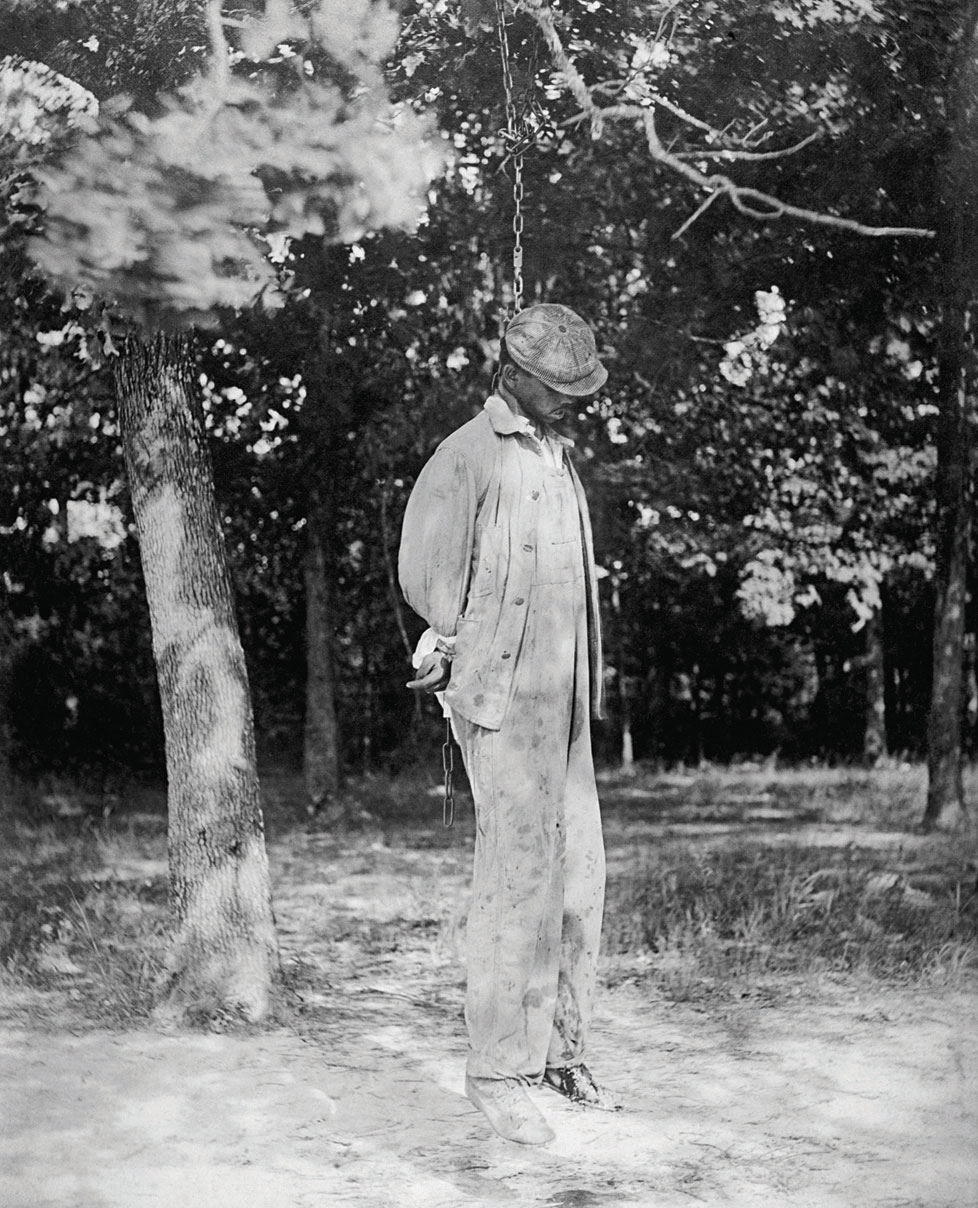

Cross burnings like this one recall the Ku Klux Klan era between the 1880s and 1960s, when white men dressed in white sheets and white hoods terrorized African Americans in the South and elsewhere and lynched more than 3,000 black men and women. Thankfully, that era is long gone, but as this news story reminds us, racial issues continue to trouble the United States.

In the wake of the 1960s urban riots, the so-called Kerner Commission (Kerner Commission, 1968)Kerner Commission. (1968). Report of the National Advisory Commission on civil disorders. New York, NY: Bantam Books. appointed by President Lyndon Johnson to study the riots famously warned, “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” The commission blamed white racism for the riots and urged the government to provide jobs and housing for African Americans and to take steps to end racial segregation.

More than four decades later, racial inequality in the United States continues to exist and in many ways has worsened. Despite major advances by African Americans, Latinos, and other people of color during the past few decades, they continue to lag behind non-Hispanic whites in education, income, health, and other social indicators. The faltering economy since 2008 has hit people of color especially hard, and the racial wealth gap is deeper now than it was just two decades ago.

Why does racial and ethnic inequality exist? What forms does it take? What can be done about it? This chapter addresses all these questions. We shall see that, although racial and ethnic inequality has stained the United States since its beginnings, there is hope for the future as long as our nation understands the structural sources of this inequality and makes a concerted effort to reduce it. Later chapters in this book will continue to highlight various dimensions of racial and ethnic inequality. Immigration, a very relevant issue today for Latinos and Asians and the source of much political controversy, receives special attention in Chapter 15 “Population and the Environment”’s discussion of population problems.

A Historical Prelude

Race and ethnicity have torn at the fabric of American society ever since the time of Christopher Columbus when an estimated 1 million Native Americans populated the eventual United States. By 1900, their numbers had dwindled to about 240,000, as tens of thousands were killed by white settlers and US troops and countless others died from disease contracted from people with European backgrounds. Scholars say this mass killing of Native Americans amounted to genocide (Brown, 2009).

African Americans also have a history of maltreatment that began during the colonial period, when Africans were forcibly transported from their homelands to be sold as slaves in the Americas. Slavery, of course, continued in the United States until the North’s victory in the Civil War ended it. African Americans outside the South were not slaves but were still victims of racial prejudice. During the 1830s, white mobs attacked free African Americans in cities throughout the nation, including Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Buffalo, and Pittsburgh. The mob violence stemmed from a “deep-seated racial prejudice…in which whites saw blacks as ‘something less than human’” (Brown, 1975) and continued well into the twentieth century, when white mobs attacked African Americans in several cities, with at least seven antiblack riots occurring in 1919 that left dozens dead. Meanwhile, an era of Jim Crow racism in the South led to the lynching of thousands of African Americans, segregation in all facets of life, and other kinds of abuses (Litwack, 2009).

African Americans were not the only targets of native-born white mobs back then (Dinnerstein & Reimers, 2009). As immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Eastern Europe, Mexico, and Asia flooded into the United States during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they, too, were beaten, denied jobs, and otherwise mistreated. During the 1850s, mobs beat and sometimes killed Catholics in cities such as Baltimore and New Orleans. During the 1870s, whites rioted against Chinese immigrants in cities in California and other states. Hundreds of Mexicans were attacked and/or lynched in California and Texas during this period.

Nazi racism in the 1930s and 1940s helped awaken Americans to the evils of prejudice in their own country. Against this backdrop, a monumental two-volume work by Swedish social scientist Gunnar Myrdal (Myrdal, 1944) attracted much attention when it was published. The book, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, documented the various forms of discrimination facing blacks back then. The “dilemma” referred to by the book’s title was the conflict between the American democratic ideals of egalitarianism and liberty and justice for all and the harsh reality of prejudice, discrimination, and lack of equal opportunity.

The Kerner Commission’s 1968 report reminded the nation that little, if anything, had been done since Myrdal’s book to address this conflict. Sociologists and other social scientists have warned since then that the status of people of color has actually been worsening in many ways since this report was issued (Massey, 2007; Wilson, 2009). Evidence of this status appears in the remainder of this chapter.

The Meaning of Race and Ethnicity

To begin our understanding of racial and ethnic inequality, we first need to understand what race and ethnicity mean. These terms may seem easy to define but are much more complex than their definitions suggest.

Race

Let’s start first with race, which refers to a category of people who share certain inherited physical characteristics, such as skin color, facial features, and stature. A key question about race is whether it is more of a biological category or a social category. Most people think of race in biological terms, and for more than three hundred years, or ever since white Europeans began colonizing nations filled with people of color, people have been identified as belonging to one race or another based on certain biological features.

It is certainly easy to see that people in the United States and around the world differ physically in some obvious ways. The most noticeable difference is skin tone: Some groups of people have very dark skin, while others have very light skin. Other differences also exist. Some people have very curly hair, while others have very straight hair. Some have thin lips, while others have thick lips. Some groups of people tend to be relatively tall, while others tend to be relatively short. Using such physical differences as their criteria, scientists at one point identified as many as nine races: African, American Indian or Native American, Asian, Australian Aborigine, European (more commonly called “white”), Indian, Melanesian, Micronesian, and Polynesian (Smedley, 2007).

Although people certainly do differ in these kinds of physical features, anthropologists, sociologists, and many biologists question the value of these categories and thus the value of the biological concept of race (Smedley, 2007). For one thing, we often see more physical differences within a race than between races. For example, some people we call “white” (or European), such as those with Scandinavian backgrounds, have very light skins, while others, such as those from some Eastern European backgrounds, have much darker skins. In fact, some “whites” have darker skin than some “blacks,” or African Americans. Some whites have very straight hair, while others have very curly hair; some have blonde hair and blue eyes, while others have dark hair and brown eyes. Because of interracial reproduction going back to the days of slavery, African Americans also differ in the darkness of their skin and in other physical characteristics. In fact, it is estimated that at least 30 percent of African Americans have some white (i.e., European) ancestry and that at least 20 percent of whites have African or Native American ancestry. If clear racial differences ever existed hundreds or thousands of years ago (and many scientists doubt such differences ever existed), in today’s world these differences have become increasingly blurred.

Another reason to question the biological concept of race is that an individual or a group of individuals is often assigned to a race arbitrarily. A century ago, for example, Irish, Italians, and Eastern European Jews who left their homelands were not regarded as white once they reached the United States but rather as a different, inferior (if unnamed) race (Painter, 2010). The belief in their inferiority helped justify the harsh treatment they suffered in their new country. Today, of course, we call people from all three backgrounds white or European.

In this context, consider someone in the United States who has a white parent and a black parent. What race is this person? American society usually calls this person black or African American, and the person may adopt this identity (as does President Barack Obama, who had a white mother and African father). But where is the logic for doing so? This person, as well as President Obama, is as much white as black in terms of parental ancestry.

Or consider someone with one white parent and another parent who is the child of one black parent and one white parent. This person thus has three white grandparents and one black grandparent. Even though this person’s ancestry is thus 75 percent white and 25 percent black, she or he is likely to be considered black in the United States and may well adopt this racial identity. This practice reflects the traditional one-drop rule in the United States that defines someone as black if she or he has at least one drop of black blood, and that was used in the antebellum South to keep the slave population as large as possible (Staples, 2005). Yet in many Latin American nations, this person would be considered white (see Note 3.7 “Lessons from Other Societies”). With such arbitrary designations, the race is more of a social category than a biological one.

Lessons from Other Societies

The Concept of Race in Brazil

As the text discusses, race was long considered a fixed, biological category, but today it is now regarded as a social construction. The experience of Brazil provides very interesting comparative evidence for this more accurate way of thinking about race.

When slaves were first brought to the Americas almost four hundred years ago, many more were taken to Brazil, where slavery was not abolished until 1888, than to the land that eventually became the United States. Brazil was then a colony of Portugal, and the Portuguese used Africans as slave labor. Just as in the United States, a good deal of interracial reproduction has occurred since those early days, much of it initially the result of the rape of women slaves by their owners, and Brazil over the centuries has had many more racial intermarriages than the United States. Also like the United States, then, much of Brazil’s population has multiracial ancestry. But in a significant departure from the United States, Brazil uses different criteria to consider the race to which a person belongs.

Brazil uses the term preto, or black, for people whose ancestry is solely African. It also uses the term Branco, or white, to refer to people whose ancestry is both African and European. In contrast, as the text discusses, the United States commonly uses the term black or African American to refer to someone with even a small amount of African ancestry and white for someone who is thought to have solely European ancestry or at least “looks” white. If the United States were to follow Brazil’s practice of reserving the term black for someone whose ancestry is solely African and the term white for someone whose ancestry is both African and European, many of the Americans commonly called “black” would no longer be considered black and instead would be considered white.

As sociologist Edward E. Telles (2006, p. 79) summarizes these differences, “[Blackness is differently understood in Brazil than in the United States. A person considered black in the United States is often not so in Brazil. Indeed, some U.S. blacks may be considered white in Brazil. Although the value given to blackness is similarly low [in both nations], who gets classified as black is not uniform.” The fact that someone can count on being considered “black” in one society and not “black” in another society underscores the idea that race is best considered a social construction rather than a biological category.

Sources: Barrionuevo & Calmes, 2011; Klein & Luno, 2009; Telles, 2006

A third reason to question the biological concept of race comes from the field of biology itself and more specifically from the studies of genetics and human evolution. Starting with genetics, people from different races are more than 99.9 percent the same in their DNA (Begley, 2008). To turn that around, less than 0.1 percent of all DNA in our bodies accounts for the physical differences among people that we associate with racial differences. In terms of DNA, then, people with different racial backgrounds are much, much more similar than dissimilar.

Even if we acknowledge that people differ in the physical characteristics we associate with race, modern evolutionary evidence reminds us that we are all, really, of one human race. According to evolutionary theory, the human race began thousands and thousands of years ago in sub-Saharan Africa. As people migrated around the world over the millennia, natural selection took over. It favored dark skin for people living in hot, sunny climates (i.e., near the equator), because the heavy amounts of melanin that produce dark skin protect against severe sunburn, cancer, and other problems. By the same token, natural selection favored light skin for people who migrated farther from the equator to cooler, less sunny climates, because dark skins there would have interfered with the production of vitamin D (Stone & Lurquin, 2007). Evolutionary evidence thus reinforces the common humanity of people who differ in the rather superficial ways associated with their appearances: We are one human species composed of people who happen to look different.

Race as a Social Construction

The reasons for doubting the biological basis for racial categories suggest that race is more of a social category than a biological one. Another way to say this is that race is a social construction, a concept that has no objective reality but rather is what people decide it is (Berger & Luckmann, 1963). In this view, the race has no real existence other than what and how people think of it.

This understanding of race is reflected in the problems, outlined earlier, in placing people with multiracial backgrounds into any one racial category. We have already mentioned the example of President Obama. As another example, golfer Tiger Woods was typically called an African American by the news media when he burst onto the golfing scene in the late 1990s, but in fact, his ancestry is one-half Asian (divided evenly between Chinese and Thai), one-quarter white, one-eighth Native American, and only one-eighth African American (Leland & Beals, 1997).

Historical examples of attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social constructionism of race. In the South during the time of slavery, the skin tone of slaves lightened over the years as babies were born from the union, often in the form of rape, of slave owners and other whites with slaves. As it became difficult to tell who was “black” and who was not, many court battles over people’s racial identity occurred. People who were accused of having black ancestry would go to court to prove they were white in order to avoid enslavement or other problems (Staples, 1998).

Although race is a social construction, it is also true that race has real consequences because people do perceive race as something real. Even though so little of DNA accounts for the physical differences we associate with racial differences, that low amount leads us not only to classify people into different races but also to treat them differently—and, more to the point, unequally—based on their classification. Yet modern evidence shows there is little if any, scientific basis for the racial classification that is the source of so much inequality.

Ethnicity

Because of the problems in the meaning of race, many social scientists prefer the term ethnicity in speaking of people of color and others with distinctive cultural heritages. In this context, ethnicity refers to the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences, stemming from common national or regional backgrounds, that make subgroups of a population different from one another. Similarly, an ethnic group is a subgroup of a population with a set of shared social, cultural, and historical experiences; with relatively distinctive beliefs, values, and behaviors; and with some sense of identity of belonging to the subgroup. So conceived, the terms ethnicity and ethnic group avoid the biological connotations of the terms race and racial group.

At the same time, the importance we attach to ethnicity illustrates that it, too, is in many ways a social construction, and our ethnic membership thus has important consequences for how we are treated. In particular, history and current practice indicate that it is easy to become prejudiced against people with different ethnicities from our own. Much of the rest of this chapter looks at the prejudice and discrimination operating today in the United States against people whose ethnicity is not white and European. Around the world today, ethnic conflict continues to rear its ugly head. The 1990s and 2000s were filled with ethnic cleansing and pitched battles among ethnic groups in Eastern Europe, Africa, and elsewhere. Our ethnic heritages shape us in many ways and fill many of us with pride, but they also are the source of much conflict, prejudice, and even hatred, as the hate crime story that began this chapter so sadly reminds us.

Dimensions of Racial and Ethnic Inequality

Racial and ethnic inequality manifests itself in all walks of life. The individual and institutional discrimination just discussed is one manifestation of this inequality. We can also see stark evidence of racial and ethnic inequality in various government statistics. Sometimes statistics lie, and sometimes they provide all too true a picture; statistics on racial and ethnic inequality fall into the latter category. Table 3.2 “Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States” presents data on racial and ethnic differences in income, education, and health.

Table 3.2 Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States

| White | African American | Latino | Asian | Native American | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median family income, 2010 ($) | 68,818 | 39,900 | 41,102 | 76,736 | 39,664 |

| Persons who are college educated, 2010 (%) | 30.3 | 19.8 | 13.9 | 52.4 | 14.9 (2008) |

| Persons in poverty, 2010 (%) | 9.9 (non-Latino) | 27.4 | 26.6 | 12.1 | 28.4 |

| Infant mortality (number of infant deaths per 1,000 births), 2006 | 5.6 | 12.9 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 8.3 |

Sources: Data from US Census Bureau. (2012). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2012. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab; US Census Bureau. (2012). American FactFinder. Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml; MacDorman, M., & Mathews, T. J. (2011). Infant Deaths—United States, 2000–2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(1), 49–51.

The picture presented by Table 3.2 “Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States” is clear: US racial and ethnic groups differ dramatically in their life chances. Compared to whites, for example, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans have much lower family incomes and much higher rates of poverty; they are also much less likely to have college degrees. In addition, African Americans and Native Americans have much higher infant mortality rates than whites: Black infants, for example, are more than twice as likely as white infants to die. Later chapters in this book will continue to highlight various dimensions of racial and ethnic inequality.

Although Table 3.2 “Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States” shows that African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans fare much worse than whites, it presents a more complex pattern for Asian Americans. Compared to whites, Asian Americans have higher family incomes and are more likely to hold college degrees, but they also have a higher poverty rate. Thus many Asian Americans do relatively well, while others fare relatively worse, as just noted. Although Asian Americans are often viewed as a “model minority,” meaning that they have achieved economic success despite not being white, some Asians have been less able than others to climb the economic ladder. Moreover, stereotypes of Asian Americans and discrimination against them remain serious problems (Chou & Feagin, 2008). Even the overall success rate of Asian Americans obscures the fact that their occupations and incomes are often lower than would be expected from their educational attainment. They thus have to work harder for their success than whites do (Hurh & Kim, 1999).

The Increasing Racial/Ethnic Wealth Gap

At the beginning of this chapter, we noted that racial and ethnic inequality has existed since the beginning of the United States. We also noted that social scientists have warned that certain conditions have actually worsened for people of color since the 1960s (Hacker, 2003; Massey & Sampson, 2009).

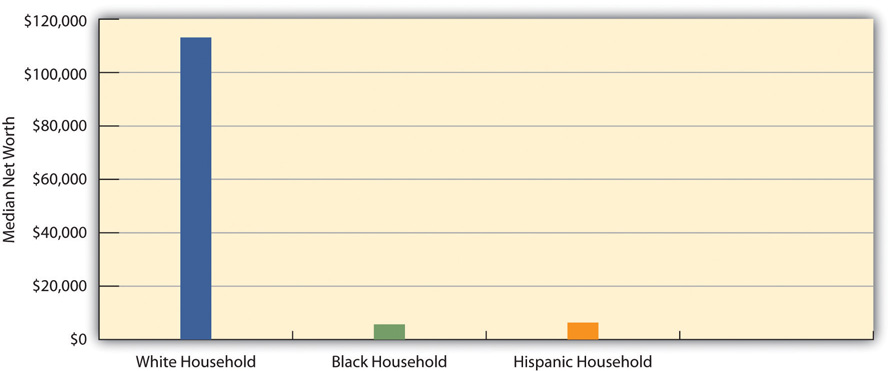

Recent evidence of this worsening appeared in a report by the Pew Research Center (2011). The report focused on racial disparities in wealth, which includes a family’s total assets (income, savings, and investments, home equity, etc.) and debts (mortgage, credit cards, etc.). The report found that the wealth gap between white households on the one hand and African American and Latino households, on the other hand, was much wider than just a few years earlier, thanks to the faltering US economy since 2008 that affected blacks more severely than whites.

According to the report, whites’ median wealth was ten times greater than blacks’ median wealth in 2007, a discouraging disparity for anyone who believes in racial equality. By 2009, however, whites’ median wealth had jumped to twenty times greater than blacks’ median wealth and eighteen times greater than Latinos’ median wealth. White households had a median net worth of about $113,000, while black and Latino households had a median net worth of only $5,700 and $6,300, respectively (see Figure 3.5 “The Racial/Ethnic Wealth Gap (Median Net Worth of Households in 2009)”). This racial and ethnic difference is the largest since the government began tracking wealth more than a quarter-century ago.

Figure 3.5 The Racial/Ethnic Wealth Gap (Median Net Worth of Households in 2009)

A large racial/ethnic gap also existed in the percentage of families with negative net worth—that is, those whose debts exceed their assets. One-third of black and Latino households had negative net worth, compared to only 15 percent of white households. Black and Latino’s households were thus more than twice as likely as white households to be in debt.

The Hidden Toll of Racial and Ethnic Inequality

An increasing amount of evidence suggests that being black in a society filled with racial prejudice, discrimination, and inequality takes what has been called a “hidden toll” on the lives of African Americans (Blitstein, 2009). As we shall see in later chapters, African Americans on the average have worse health than whites and die at younger ages. In fact, every year there are an additional 100,000 African American deaths than would be expected if they lived as long as whites do. Although many reasons probably explain all these disparities, scholars are increasingly concluding that the stress of being black is a major factor (Geronimus et al., 2010).

In this way of thinking, African Americans are much more likely than whites to be poor, to live in high-crime neighborhoods, and to live in crowded conditions, among many other problems. As this chapter discussed earlier, they are also more likely, whether or not they are poor, to experience racial slights, refusals to be interviewed for jobs, and other forms of discrimination in their everyday lives. All these problems mean that African Americans from their earliest ages grow up with a great deal of stress, far more than what most whites experience. This stress, in turn, has certain neural and physiological effects, including hypertension (high blood pressure), that impair African Americans’ short-term and long-term health and that ultimately shorten their lives. These effects accumulate over time: black and white hypertension rates are equal for people in their twenties, but the black rate becomes much higher by the time people reach their forties and fifties. As a recent news article on evidence of this “hidden toll” summarized this process, “The long-term stress of living in a white-dominated society ‘weathers’ blacks, making them age faster than their white counterparts” (Blitstein, 2009, p. 48).

Although there is less research on other people of color, many Latinos and Native Americans also experience the various sources of stress that African Americans experience. To the extent this is true, racial and ethnic inequality also takes a hidden toll on members of these two groups. They, too, experience racial slights, live under disadvantaged conditions, and face other problems that result in high levels of stress and shorten their life spans.

White Privilege: The Benefits of Being White

Before we leave this section, it is important to discuss the advantages that US whites enjoy in their daily lives simply because they are white. Social scientists term these advantages white privilege and say that whites benefit from being white whether or not they are aware of their advantages (McIntosh, 2007).

This chapter’s discussion of the problems facing people of color points to some of these advantages. For example, whites can usually drive a car at night or walk down a street without having to fear that a police officer will stop them simply because they are white. Recalling the Trayvon Martin tragedy, they can also walk down a street without having to fear they will be confronted and possibly killed by a neighborhood watch volunteer. In addition, whites can count on being able to move into any neighborhood they desire to as long as they can afford the rent or mortgage. They generally do not have to fear being passed up for a promotion simply because of their race. White students can live in college dorms without having to worry that racial slurs will be directed their way. White people, in general, do not have to worry about being the victims of hate crimes based on their race. They can be seated in a restaurant without having to worry that they will be served more slowly or not at all because of their skin color. If they are in a hotel, they do not have to think that someone will mistake them for a bellhop, parking valet, or maid. If they are trying to hail a taxi, they do not have to worry about the taxi driver ignoring them because the driver fears he or she will be robbed.

Social scientist Robert W. Terry (1981, p. 120) once summarized white privilege as follows: “To be white in America is not to have to think about it. Except for hard-core racial supremacists, the meaning of being white is having the choice of attending to or ignoring one’s own whiteness” (emphasis in original). For people of color in the United States, it is not an exaggeration to say that race and ethnicity are a daily fact of their existence. Yet whites do not generally have to think about being white. As all of us go about our daily lives, this basic difference is one of the most important manifestations of racial and ethnic inequality in the United States.

Perhaps because whites do not have to think about being white, many studies find they tend to underestimate the degree of racial inequality in the United States by assuming that African Americans and Latinos are much better off than they really are. As one report summarized these studies’ overall conclusion, “Whites tend to have a relatively rosy impression of what it means to be a black person in America. Whites are more than twice as likely as blacks to believe that the position of African Americans has improved a great deal” (Vedantam, 2008, p. A3). Because whites think African Americans and Latinos fare much better than they really do, that perception probably reduces whites’ sympathy for programs designed to reduce racial and ethnic inequality.

Explaining Racial and Ethnic Inequality

Why does racial and ethnic inequality exist? Why do African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and some Asian Americans fare worse than whites? In answering these questions, many people have some very strong opinions.

Biological Inferiority

One long-standing explanation is that blacks and other people of color are biologically inferior: They are naturally less intelligent and have other innate flaws that keep them from getting a good education and otherwise doing what needs to be done to achieve the American Dream. As discussed earlier, this racist view is no longer common today. However, whites historically used this belief to justify slavery, lynchings, the harsh treatment of Native Americans in the 1800s, and lesser forms of discrimination. In 1994, Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray revived this view in their controversial book, The Bell Curve (Herrnstein & Murray, 1994), in which they argued that the low IQ scores of African Americans, and of poor people more generally, reflect their genetic inferiority in the area of intelligence. African Americans’ low innate intelligence, they said, accounts for their poverty and other problems. Although the news media gave much attention to their book, few scholars agreed with its views, and many condemned the book’s argument as a racist way of “blaming the victim” (Gould, 1994).

Cultural Deficiencies

Another explanation of racial and ethnic inequality focuses on the supposed cultural deficiencies of African Americans and other people of color (Murray, 1984). These deficiencies include a failure to value hard work and, for African Americans, a lack of strong family ties, and are said to account for the poverty and other problems facing these minorities. This view echoes the culture-of-poverty argument presented in Chapter 2 “Poverty” and is certainly popular today. As we saw earlier, more than half of non-Latino whites think that blacks’ poverty is due to their lack of motivation and willpower. Ironically some scholars find support for this cultural deficiency view in the experience of many Asian Americans, whose success is often attributed to their culture’s emphasis on hard work, educational attainment, and strong family ties (Min, 2005). If that is true, these scholars say, then the lack of success of other people of color stems from the failure of their own cultures to value these attributes.

How accurate is the cultural deficiency argument? Whether people of color have “deficient” cultures remains hotly debated (Bonilla-Silva, 2009). Many social scientists find little or no evidence of cultural problems in minority communities and say the belief in cultural deficiencies is an example of symbolic racism that blames the victim. Citing survey evidence, they say that poor people of color value work and education for themselves and their children at least as much as wealthier white people do (Holland, 2011; Muhammad, 2007). Yet other social scientists, including those sympathetic to the structural problems facing people of color, believe that certain cultural problems do exist, but they are careful to say that these cultural problems arise out of the structural problems. For example, Elijah Anderson (1999) wrote that a “street culture” or “oppositional culture” exists among African Americans in urban areas that contribute to high levels of violent behavior, but he emphasized that this type of culture stems from the segregation, extreme poverty, and other difficulties these citizens face in their daily lives and helps them deal with these difficulties. Thus even if cultural problems do exist, they should not obscure the fact that structural problems are responsible for the cultural ones.

Structural Problems

A third explanation for US racial and ethnic inequality is based on conflict theory and reflects the blaming-the-system approach outlined in Chapter 1 “Understanding Social Problems”. This view attributes racial and ethnic inequality to structural problems, including institutional and individual discrimination, a lack of opportunity in education and other spheres of life, and the absence of jobs that pay an adequate wage (Feagin, 2006). Segregated housing, for example, prevents African Americans from escaping the inner city and from moving to areas with greater employment opportunities. Employment discrimination keeps the salaries of people of color much lower than they would be otherwise. The schools that many children of color attend every day are typically overcrowded and underfunded. As these problems continue from one generation to the next, it becomes very difficult for people already at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder to climb up it because of their race and ethnicity (see Note 3.33 “Applying Social Research”).

Applying Social Research

The Poor Neighborhoods of Middle-Class African Americans

In a society that values equal opportunity for all, scholars have discovered a troubling trend: African American children from middle-class families are much more likely than white children from middle-class families to move down the socioeconomic ladder by the time they become adults. In fact, almost half of all African American children born during the 1950s and 1960s to middle-class parents ended up with lower incomes than their parents by adulthood. Because these children had parents who had evidently succeeded despite all the obstacles facing them in a society filled with racial inequality, we have to assume they were raised with the values, skills, and aspirations necessary to stay in the middle class and even to rise beyond it. What, then, explains why some end up doing worse than their parents?

According to a recent study written by sociologist Patrick Sharkey for the Pew Charitable Trusts, one important answer lies in the neighborhoods in which these children are raised. Because of continuing racial segregation, many middle-class African American families find themselves having to live in poor urban neighborhoods. About half of African American children born between 1955 and 1970 to middle-class parents grew up in poor neighborhoods, but hardly any middle-class white children grew up in such neighborhoods. In Sharkey’s statistical analysis, neighborhood poverty was a much more important factor than variables such as parents’ education and marital status in explaining the huge racial difference in the eventual socioeconomic status of middle-class children. An additional finding of the study underscored the importance of neighborhood poverty for adult socioeconomic status: African American children raised in poor neighborhoods in which the poverty rate declined significantly ended up with higher incomes as adults than those raised in neighborhoods where the poverty rate did not change.

Why do poor neighborhoods have this effect? It is difficult to pinpoint the exact causes, but several probable reasons come to mind. In these neighborhoods, middle-class African American children often receive inadequate schooling at run-down schools, and they come under the influence of youths who care much less about schooling and who get into various kinds of trouble. The various problems associated with living in poor neighborhoods also likely cause a good deal of stress, which, as discussed elsewhere in this chapter, can cause health problems and impair learning ability.

Even if the exact reasons remain unclear, this study showed that poor neighborhoods make a huge difference. As a Pew official summarized the study, “We’ve known that neighborhood matters…but this does it in a new and powerful way. Neighborhoods become a significant drag not just on the poor, but on those who would otherwise be stable.” Sociologist Sharkey added, “What surprises me is how dramatic the racial differences are in terms of the environments in which children are raised. There’s this perception that after the civil rights period, families have been more able to seek out any neighborhood they choose and that…the racial gap in neighborhoods would whittle away over time, and that hasn’t happened.”

Data from the 2010 Census confirm that the racial gap in neighborhoods persists. A study by sociologist John R. Logan for the Russell Sage Foundation found that African American and Latino families with incomes above $75,000 are more likely to live in poor neighborhoods than non-Latino white families with incomes below $40,000. More generally, Logan concluded, “The average affluent black or Hispanic household lives in a poorer neighborhood than the average lower-income white household.”

One implication of this neighborhood research is clear: to help reduce African American poverty, it is important to do everything possible to improve the quality and economy of the poor neighborhoods in which many African American children, middle-class or poor, grow up.

Sources: Logan, 2011; MacGillis, 2009; Sharkey, 2009

As we assess the importance of structure versus culture in explaining why people of color have higher poverty rates, it is interesting to consider the economic experience of African Americans and Latinos since the 1990s. During that decade, the US economy thrived. Along with this thriving economy, unemployment rates for African Americans and Latinos declined and their poverty rates also declined. Since the early 2000s and especially since 2008, the US economy has faltered. Along with this faltering economy, unemployment and poverty rates for African Americans and Latinos increased.

To explain these trends, does it make sense to assume that African Americans and Latinos somehow had fewer cultural deficiencies during the 1990s and more cultural deficiencies since the early 2000s? Or does it make sense to assume that their economic success or lack of it depended on the opportunities afforded them by the US economy? Economic writer Joshua Holland (2011) provides the logical answer by attacking the idea of cultural deficiencies: “That’s obviously nonsense. It was exogenous economic factors and changes in public policies, not manifestations of ‘black culture’ [or ‘Latino culture’], that resulted in those widely varied outcomes…While economic swings this significant can be explained by economic changes and different public policies, it’s simply impossible to fit them into a cultural narrative.”

Reducing Racial and Ethnic Inequality

Now that we have examined race and ethnicity in the United States, what have we found? Where do we stand in the second decade of the twenty-first century? Did the historic election of Barack Obama as president in 2008 signify a new era of equality between the races, as many observers wrote, or did his election occur despite the continued existence of pervasive racial and ethnic inequality?

On the one hand, there is cause for hope. Legal segregation is gone. The vicious, “old-fashioned” racism that was so rampant in this country into the 1960s has declined dramatically since that tumultuous time. People of color have made important gains in several spheres of life, and African Americans and other people of color occupy some important elected positions in and outside the South, a feat that would have been unimaginable a generation ago. Perhaps most notably, Barack Obama has African ancestry and identifies as an African American, and on his 2008 election night, people across the country wept with joy at the symbolism of his victory. Certainly, progress has been made in US racial and ethnic relations.

On the other hand, there is also cause for despair. Old-fashioned racism has been replaced by modern, symbolic racism that still blames people of color for their problems and reduces public support for government policies to deal with their problems. Institutional discrimination remains pervasive, and hate crimes, such as the cross-burning that began this chapter, remain all too common. So does suspicion of people based solely on the color of their skin, as the Trayvon Martin tragedy again reminds us.

If adequately funded and implemented, several types of programs and policies show a strong promise of reducing racial and ethnic inequality. We turn to these in a moment, but first let’s discuss affirmative action, an issue that has aroused controversy since its inception.

People Making a Difference

College Students and the Southern Civil Rights Movement

The first chapter of this book included this famous quotation by anthropologist Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” The beginnings of the Southern civil rights movement provide an inspirational example of Mead’s wisdom and remind us that young people can make a difference.

Although there had been several efforts during the 1950s by African Americans to end legal segregation in the South, the start of the civil rights movement is commonly thought to have begun on February 1, 1960. On that historic day, four brave African American students from the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina, dressed in coats and ties, sat down quietly at a segregated lunch counter in a Woolworth’s store in the city of Greensboro and asked to be served. When they were refused service, they stayed until the store closed at the end of the day, and then went home. They returned the next day and were joined by some two dozen other students. They were again refused service and sat quietly for the rest of the day. The next day some sixty students and other people joined them, followed by some three hundred on the fourth day. Within a week, sit-ins were occurring at lunch counters in several other towns and cities inside and outside of North Carolina. In late July 1960, the Greensboro Woolworth’s finally served African Americans, and the entire Woolworth’s chain desegregated its lunch counters a day later. Although no one realized it at the time, the civil rights movement had “officially” begun thanks to the efforts of a small group of college students.

During the remaining years of the heyday of the civil rights movement, college students from the South and North joined thousands of other people in sit-ins, marches, and other activities to end legal segregation. Thousands were arrested, and at least forty-one were murdered. By risking their freedom and even their lives, they made a difference for millions of African Americans. And it all began when a small group of college students sat down at a lunch counter in Greensboro and politely refused to leave until they were served.

Sources: Branch, 1988; Southern Poverty Law Center, 2011

Affirmative Action

Affirmative action refers to special consideration for minorities and women in employment and education to compensate for the discrimination and lack of opportunities they experience in the larger society. Affirmative action programs were begun in the 1960s to provide African Americans and, later, other people of color and women access to jobs and education to make up for past discrimination. President John F. Kennedy was the first known official to use the term, when he signed an executive order in 1961 ordering federal contractors to “take affirmative action” in ensuring that applicants are hired and treated without regard to their race and national origin. Six years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson added sex to race and national origin as demographic categories for which affirmative action should be used.

Although many affirmative action programs remain in effect today, court rulings, state legislation, and other efforts have limited their number and scope. Despite this curtailment, affirmative action continues to spark much controversy, with scholars, members of the public, and elected officials all holding strong views on the issue.

One of the major court rulings just mentioned was the US Supreme Court’s decision in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 US 265 (1978). Allan Bakke was a 35-year-old white man who had twice been rejected for admission into the medical school at the University of California, Davis. At the time he applied, UC–Davis had a policy of reserving sixteen seats in its entering class of one hundred for qualified people of color to make up for their underrepresentation in the medical profession. Bakke’s college grades and scores on the Medical College Admission Test were higher than those of the people of color admitted to UC–Davis either time Bakke applied. He sued for admission on the grounds that his rejection amounted to reverse racial discrimination on the basis of his being white (Stefoff, 2005).

The case eventually reached the Supreme Court, which ruled 5–4 that Bakke must be admitted into the UC–Davis medical school because he had been unfairly denied admission on the basis of his race. As part of its historic but complex decision, the Court thus rejected the use of strict racial quotas in admission, as it declared that no applicant could be excluded based solely on the applicant’s race. At the same time, however, the Court also declared that race may be used as one of the several criteria that admissions committees consider when making their decisions. For example, if an institution desires racial diversity among its students, it may use race as an admissions criterion along with other factors such as grades and test scores.

Two more recent Supreme Court cases both involved the University of Michigan: Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 US 244 (2003), which involved the university’s undergraduate admissions, and Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 US 306 (2003), which involved the university’s law school admissions. In Grutter the Court reaffirmed the right of institutions of higher education to take race into account in the admissions process. In Gratz, however, the Court invalidated the university’s policy of awarding additional points to high school students of color as part of its use of a point system to evaluate applicants; the Court said that consideration of applicants needed to be more individualized than a point system allowed.

Drawing on these Supreme Court rulings, then, affirmative action in higher education admissions on the basis of race/ethnicity is permissible as long as it does not involve a rigid quota system and as long as it does involve an individualized way of evaluating candidates. Race may be used as one of several criteria in such an individualized evaluation process, but it must not be used as the only criterion.

The Debate over Affirmative Action

Opponents of affirmative action cite several reasons for opposing it (Connors, 2009). Affirmative action, they say, is reverse discrimination and, as such, is both illegal and immoral. The people benefiting from affirmative action are less qualified than many of the whites with whom they compete for employment and college admissions. In addition, opponents say, affirmative action implies that the people benefiting from it need extra help and thus are indeed less qualified. This implication stigmatizes the groups benefiting from affirmative action.

In response, proponents of affirmative action give several reasons for favoring it (Connors, 2009). Many say it is needed to make up not just for past discrimination and a lack of opportunities for people of color but also for ongoing discrimination and a lack of opportunity. For example, because of their social networks, whites are much better able than people of color to find out about and to get jobs (Reskin, 1998). If this is true, people of color are automatically at a disadvantage in the job market, and some form of affirmative action is needed to give them an equal chance at employment. Proponents also say that affirmative action helps add diversity to the workplace and to the campus. Many colleges, they note, give some preference to high school students who live in a distant state in order to add needed diversity to the student body; to “legacy” students—those with a parent who went to the same institution—to reinforce alumni loyalty and to motivate alumni to donate to the institution; and to athletes, musicians, and other applicants with certain specialized talents and skills. If all these forms of preferential admission make sense, proponents say, it also makes sense to take students’ racial and ethnic backgrounds into account as admissions officers strive to have a diverse student body.

Proponents add that affirmative action has indeed succeeded in expanding employment and educational opportunities for people of color and that individuals benefiting from affirmative action have generally fared well in the workplace or on the campus. In this regard, research finds that African American students graduating from selective US colleges and universities after being admitted under affirmative action guidelines are slightly more likely than their white counterparts to obtain professional degrees and to become involved in civic affairs (Bowen & Bok, 1998).

As this brief discussion indicates, several reasons exist for and against affirmative action. A cautious view is that affirmative action may not be perfect but that some form of it is needed to make up for past and ongoing discrimination and lack of opportunity in the workplace and on the campus. Without the extra help that affirmative action programs give disadvantaged people of color, the discrimination and other difficulties they face are certain to continue.

Other Programs and Policies

As indicated near the beginning of this chapter, one message from DNA evidence and studies of evolution is that we are all part of one human race. If we fail to recognize this lesson, we are doomed to repeat the experiences of the past, when racial and ethnic hostility overtook good reason and subjected people who happened to look different from the white majority to legal, social, and violent oppression. In the democracy that is America, we must try to do better so that there will truly be “liberty and justice for all.”

As the United States attempts, however haltingly, to reduce racial and ethnic inequality, sociology has much insight to offer in its emphasis on the structural basis for this inequality. This emphasis strongly indicates that racial and ethnic inequality has much less to do with any personal faults of people of color than with the structural obstacles they face, including ongoing discrimination and lack of opportunity. Efforts aimed at such obstacles, then, are in the long run essential to reducing racial and ethnic inequality (Danziger, Reed, & Brown, 2004; Syme, 2008; Walsh, 2011). Some of these efforts resemble those for reducing poverty discussed in Chapter 2 “Poverty”, given the greater poverty of many people of color, and include the following:

- Adopt a national “full employment” policy involving federally funded job training and public works programs.

- Increase federal aid for the working poor, including earned income credits and child-care subsidies for those with children.

- Establish and expand well-funded early childhood intervention programs, including home visitation by trained professionals, for poor families, as well as adolescent intervention programs, such as Upward Bound, for low-income teenagers.

- Improve the schools that poor children attend and the schooling they receive, and expand early childhood education programs for poor children.

- Provide better nutrition and health services for poor families with young children.

- Strengthen efforts to reduce teenage pregnancies.

- Strengthen affirmative action programs within the limits imposed by court rulings.

- Strengthen legal enforcement of existing laws forbidding racial and ethnic discrimination in hiring and promotion.

- Strengthen efforts to reduce residential segregation.

Key Takeaways

- Racial and ethnic prejudice and discrimination have been an “American dilemma” in the United States ever since the colonial period. Slavery was only the ugliest manifestation of this dilemma. The urban riots of the 1960s led to warnings about the racial hostility and discrimination confronting African Americans and other groups, and these warnings continue down to the present.

- Social scientists today tend to consider race more of a social category than a biological one for several reasons. Race is thus best considered a social construction and not a fixed biological category.

- Ethnicity refers to a shared cultural heritage and is a term increasingly favored by social scientists over race. Membership in ethnic groups gives many people an important sense of identity and pride but can also lead to hostility toward people in other ethnic groups.

- Prejudice, racism, and stereotypes all refer to negative attitudes about people based on their membership in racial or ethnic categories. Social-psychological explanations of prejudice focus on scapegoating and authoritarian personalities, while sociological explanations focus on conformity and socialization or on economic and political competition. Jim Crow racism has given way to modern or symbolic racism that considers people of color to be culturally inferior.

- Discrimination and prejudice often go hand in hand, but not always. People can discriminate without being prejudiced, and they can be prejudiced without discriminating. Individual and institutional discrimination both continue to exist in the United States.

- Racial and ethnic inequality in the United States is reflected in income, employment, education, and health statistics. In their daily lives, whites enjoy many privileges denied to their counterparts in other racial and ethnic groups.

- On many issues Americans remain sharply divided along racial and ethnic lines. One of the most divisive issues is affirmative action. Its opponents view it among other things as reverse discrimination, while its proponents cite many reasons for its importance, including the need to correct past and present discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities.

Critical Thinking

After graduating from college, you obtain a job in a medium-sized city in the Midwest and rent an apartment in a house in a nearby town. A family with an African American father and white mother has recently moved into a house down the street. You think nothing of it, but you begin to hear some of the neighbors expressed concern that the neighborhood “has begun to change.” Then one night a brick is thrown through the window of the new family’s home, and around the brick is wrapped the message, “Go back to where you came from!” Since you’re new to the neighborhood yourself, you don’t want to make waves, but you are also shocked by this act of racial hatred. You can speak up somehow or you can stay quiet. What do you decide to do? Why?

What You Can Do

-

To help reduce racial and ethnic inequality, you may wish to do any of the following:

- Contribute money to a local, state, or national organization that tries to help youths of color at their schools, homes, or other venues.

- Volunteer for an organization that focuses on policy issues related to race and ethnicity.

- Volunteer for any programs at your campus that aim at enhancing the educational success of new students of color; if no such programs exist, start one.

References

Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Barrionuevo, A., & Calmes, J. (2011, March 21). President underscores similarities with Brazilians but sidesteps one. New York Times, p. A8.

Begley, S. (2008, February 29). Race and DNA. Newsweek. Retrieved from http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/blogs/lab-notes/2008/02/29/race-and-dna.html.

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1963). The social construction of reality. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Blitstein, R. (2009). Weathering the storm. Miller-McCune, 2(July–August), 48–57.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2009). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States (3rd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bowen, W. G., & Bok, D. C. (1998). The shape of the river: Long-term consequences of considering race in college and university admissions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Branch, T. (1988). Parting the waters: America in the King years, 1954–1963. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Brown, D. A. (2009). Bury my heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian history of the American West. New York, NY: Sterling Innovation.

Brown, R. M. (1975). Strain of violence: Historical studies of American violence and vigilantism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Chou, R. S., & Feagin, J. R. (2008). The myth of the model minority: Asian Americans facing racism. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

Connors, P. (Ed.). (2009). Affirmative action. Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven Press.

Danziger, S., Reed, D., & Brown, T. N. (2004). Poverty and prosperity: Prospects for reducing racial economic disparities in the United States. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

Dinnerstein, L., & Reimers, D. M. (2009). Ethnic Americans: A history of immigration. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Feagin, J. R. (2006). Systematic racism: A theory of oppression. New York, NY: Routledge.

Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Pearson, J., Seashols, S., Brown, K., & Cruz., T. D. (2010). Do US black women experience stress-related accelerated biological aging? Human Nature: An Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective, 21, 19–38.

Gould, S. J. (1994, November 28). Curveball. The New Yorker, pp. 139–149.

Hacker, A. (2003). Two nations: Black and white, separate, hostile, unequal (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Scribner.

Herrnstein, R. J., & Murray, C. (1994). The bell curve: Intelligence and class structure in American life. New York, NY: Free Press.

Holland, J. (2011, July 29). Debunking the big lie right-wingers use to justify black poverty and unemployment. AlterNet. Retrieved from http://www.alternet.org/teaparty/151830/debunking_the_big_lie_right-wingers_use_to_justify_black_poverty _and_unemployment_.

Hurh, W. M., & Kim, K. C. (1999). The “success” image of Asian Americans: Its validity, and its practical and theoretical implications. In C. G. Ellison & W. A. Martin (Eds.), Race and ethnic relations in the United States (pp. 115–122). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Jablon, R. (2011, March 23). Anger, shock over cross burning in Calif. community. washingtonpost.com. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/03/23/AR2011032300301.html.

Kerner Commission. (1968). Report of the National Advisory Commission on civil disorders. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Klein, H. S., & Luno, F. V. (2009). Slavery in Brazil. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Leland, J., & Beals, G. (1997, May 5). In living colors: Tiger Woods is the exception that rules. Newsweek, 58–60.

Lerner, D. (2011, July 22). Police chief says suspects wanted to “terrorize” cross burning victim. ksby.com. Retrieved from http://www.ksby.com/news/police-chief-says-suspects-wanted-to-terrorize-cross-burning-victim/.

Litwack, L. F. (2009). How free is free? The long death of Jim Crow. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Logan, J. R. (2011). Separate and unequal: The neighborhood gap for blacks, Hispanics and Asians in metropolitan America. New York, NY: US201 Project.

MacGillis, A. (2009, July 27). Neighborhoods key to future income, study finds. The Washington Post, p. A06.

Mann, C. (2011, March 22). Cross burning in Calif. suburb brings FBI into hate crime investigation. cbsnews.com. Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/.

Massey, D. S. (2007). Categorically unequal: The American stratification system. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, D. S., & Sampson, R. J. (2009). Moynihan redux: Legacies and lessons. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621, 6–27.

McIntosh, P. (2007). White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondence through work in women’s studies. In M. L. Andersen & P. H. Collins (Eds.), Race, class, and gender: An anthology (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Min, P. G. (Ed.). (2005). Asian Americans: Contemporary trends and issues (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Muhammad, K. G. (2007, December 9). White may be might, but it’s not always right. The Washington Post, p. B3.

Murray, C. (1984). Losing ground: American social policy, 1950–1980. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Myrdal, G. (1944). An American dilemma: The negro problem and modern democracy. New York, NY: Harper and Brothers.

Painter, N. I. (2010). The history of white people. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Pew Research Center. (2011). Twenty-to-one: Wealth gaps rise to record highs between whites, blacks and Hispanics. Washington, DC: Author.

Reskin, B. F. (1998). Realities of affirmative action in employment. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association.

Sharkey, P. (2009). Neighborhoods and the black-white mobility gap. Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts.

Smedley, A. (2007). Race in North America: Evolution of a worldview. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Southern Poverty Law Center. (2011). 41 lives for freedom. Retrieved from http://www.crmvet.org/mem/41lives.htm.

Staples, B. (1998, November 13). The shifting meanings of “black” and “white.” New York Times, p. WK14.

Staples, B. (2005, October 31). Why race isn’t as “black” and “white” as we think. New York Times, p. A18.

Stefoff, R. (2005). The Bakke case: Challenging affirmative action. New York, NY: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark.

Stone, L., & Lurquin, P. F. (2007). Genes, culture, and human evolution: A synthesis. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Syme, S. L. (2008). Reducing racial and social-class inequalities in health: The need for a new approach. Health Affairs, 27, 456–459.

Telles, E. E. (2006). Race in another America: The significance of skin color in Brazil. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Terry, R. W. (1981). The negative impact on white values. In B. P. Bowser & R. G. Hunt (Eds.), Impacts of racism on white Americans (pp. 119–151). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Vedantam, S. (2008, March 24). Unequal perspectives on racial equality. The Washington Post, p. A3.

Walsh, R. (2011). Helping or hurting: Are adolescent intervention programs minimizing racial inequality? Education & Urban Society, 43(3), 370–395.

Wilson, W. J. (2009). The economic plight of inner-city black males. In E. Anderson (Ed.), Against the wall: Poor, young, black, and male (pp. 55–70). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 3.1, 3.2, 3.5, 3.6, 3.7, and 3.8 from Social Problems by the University of Minnesota under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.