Chapter 18: Psychosocial Development in Middle Childhood

Chapter 18 Learning Objectives

- Describe Erikson’s fourth stage of industry vs. inferiority

- Describe the changes in self-concept, self-esteem, and self-efficacy

- Explain Kohlberg’s stages of moral development

- Describe the importance of peers, the stages of friendships, peer acceptance, and the consequences of peer acceptance

- Describe bullying, cyberbullying and the consequences of bullying

- Identify the types of families where children reside

- Identify the five family tasks

- Explain the consequences of divorce on children

- Describe the effects of cohabitation and remarriage on children

- Describe the characteristics and developmental stages of blended families

Erikson: Industry vs. Inferiority

According to Erikson, children in middle and late childhood are very busy or industrious (Erikson, 1982). They are constantly doing, planning, playing, getting together with friends, and achieving. This is a very active time, and a time when they are gaining a sense of how they measure up when compared with peers. Erikson believed that if these industrious children can be successful in their endeavors, they will get a sense of confidence for future challenges. If not, a sense of inferiority can be particularly haunting during middle and late childhood.

Self-Understanding

Self-concept refers to beliefs about general personal identity (Seiffert, 2011). These beliefs include personal attributes, such as one’s age, physical characteristics, behaviors, and competencies. Children in middle and late childhood have a more realistic sense of self than do those in early childhood, and they better understand their strengths and weaknesses. This can be attributed to greater experience in comparing their own performance with that of others, and to greater cognitive flexibility. Children in middle and late childhood are also able to include other peoples’ appraisals of them into their self-concept, including parents, teachers, peers, culture, and media. Internalizing others’ appraisals and creating social comparison affect children’s self-esteem, which is defined as an evaluation of one’s identity. Children can have individual assessments of how well they perform a variety of activities and also develop an overall global self-assessment. If there is a discrepancy between how children view themselves and what they consider to be their ideal selves, their self-esteem can be negatively affected.

Another important development in self-understanding is self-efficacy, which is the belief that you are capable of carrying out a specific task or of reaching a specific goal (Bandura, 1977, 1986, 1997). Large discrepancies between self-efficacy and ability can create motivational problems for the individual (Seifert, 2011). If a student believes that he or she can solve mathematical problems, then the student is more likely to attempt the mathematics homework that the teacher assigns.

Unfortunately, the converse is also true. If a student believes that he or she is incapable of math, then the student is less likely to attempt the math homework regardless of the student’s actual ability in math. Since self-efficacy is self-constructed, it is possible for students to miscalculate or misperceive their true skill, and these misperceptions can have complex effects on students’ motivations. It is possible to have either too much or too little self-efficacy, and according to Bandura (1997) the optimum level seems to be either at or slightly above, true ability.

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

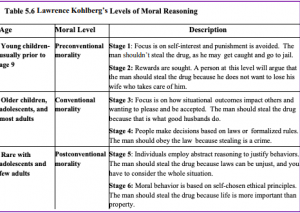

Kohlberg (1963) built on the work of Piaget and was interested in finding out how our moral reasoning changes as we get older. He wanted to find out how people decide what is right and what is wrong. Just as Piaget believed that children’s cognitive development follows specific patterns, Kohlberg (1984) argued that we learn our moral values through active thinking and reasoning, and that moral development follows a series of stages. Kohlberg’s six stages are generally organized into three levels of moral reasons. To study moral development, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to children, teenagers, and adults, such as the following:

A man’s wife is dying of cancer and there is only one drug that can save her. The only place to get the drug is at the store of a pharmacist who is known to overcharge people for drugs. The man can only pay $1,000, but the pharmacist wants $2,000, and refuses to sell it to him for less, or to let him pay later. Desperate, the man later breaks into the pharmacy and steals the medicine. Should he have done that? Was it right or wrong? Why? (Kohlberg, 1984)

Level One-Preconventional Morality: In stage one, moral reasoning is based on concepts of punishment. The child believes that if the consequence for an action is punishment, then the action was wrong. In the second stage, the child bases his or her thinking on self-interest and reward. “You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” The youngest subjects seemed to answer based on what would happen to the man as a result of the act. For example, they might say the man should not break into the pharmacy because the pharmacist might find him and beat him. Or they might say that the man should break in and steal the drug and his wife will give him a big kiss. Right or wrong, both decisions were based on what would physically happen to the man as a result of the act. This is a self-centered approach to moral decision-making. He called this most superficial understanding of right and wrong pre-conventional morality. Preconventional morality focuses on self-interest. Punishment is avoided, and rewards are sought. Adults can also fall into these stages, particularly when they are under pressure.

Level Two-Conventional Morality: Those tested who based their answers on what other people would think of the man as a result of his act, were placed in Level Two. For instance, they might say he should break into the store, and then everyone would think he was a good husband, or he should not because it is against the law. In either case, right and wrong is determined by what other people think. In stage three, the person wants to please others. At stage four, the person acknowledges the importance of social norms or laws and wants to be a good member of the group or society. A good decision is one that gains the approval of others or one that complies with the law. This he called conventional morality, people care about the effect of their actions on others. Some older children, adolescents, and adults use this reasoning.

Level Three-Postconventional Morality: Right and wrong are based on social contracts established for the good of everyone and that can transcend the self and social convention. For example, the man should break into the store because, even if it is against the law, the wife needs the drug and her life is more important than the consequences the man might face for breaking the law. Alternatively, the man should not violate the principle of the right of property because this rule is essential for social order. In either case, the person’s judgment goes beyond what happens to the self. It is based on a concern for others; for society as a whole, or for an ethical standard rather than a legal standard. This level is called post-conventional moral development because it goes beyond convention or what other people think to a higher, universal ethical principle of conduct that may or may not be reflected in the law. Notice that such thinking is the kind Supreme Court justices do all day when deliberating whether a law is moral or ethical, which requires being able to think abstractly. Often this is not accomplished until a person reaches adolescence or adulthood. In the fifth stage, laws are recognized as social contracts. The reasons for the laws, like justice, equality, and dignity, are used to evaluate decisions and interpret laws. In the sixth stage, individually determined universal ethical principles are weighed to make moral decisions. Kohlberg said that few people ever reach this stage. The six stages can be reviewed in Table 5.6.

Although research has supported Kohlberg’s idea that moral reasoning changes from an early emphasis on punishment and social rules and regulations to an emphasis on more general ethical principles, as with Piaget’s approach, Kohlberg’s stage model is probably too simple. For one, people may use higher levels of reasoning for some types of problems but revert to lower levels in situations where doing so is more consistent with their goals or beliefs (Rest, 1979). Second, it has been argued that the stage model is particularly appropriate for Western, rather than nonWestern, samples in which allegiance to social norms, such as respect for authority, may be particularly important (Haidt, 2001). In addition, there is frequently little correlation between how we score on the moral stages and how we behave in real life.

Table 5.6

Perhaps the most important critique of Kohlberg’s theory is that it may describe the moral development of males better than it describes that of females. Gilligan (1982) has argued that, because of differences in their socialization, males tend to value principles of justice and rights, whereas females value caring for and helping others. Although there is little evidence for a gender difference in Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (Turiel, 1998), it is true that girls and women tend to focus more on issues of caring, helping, and connecting with others than do boys and men (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000).

Friends and Peers

As toddlers, children may begin to show a preference for certain playmates (Ross & Lollis, 1989). However, peer interactions at this age often involve more parallel play rather than intentional social interactions (Pettit, Clawson, Dodge, & Bates, 1996). By age four, many children use the word “friend” when referring to certain children and do so with a fair degree of stability (Hartup, 1983). However, among young children “friendship” is often based on proximity, such as they live next door, attend the same school, or it refers to whomever they just happen to be playing with at the time (Rubin, 1980).

Friendships take on new importance as judges of one’s worth, competence, and attractiveness in middle and late childhood. Friendships provide the opportunity for learning social skills, such as how to communicate with others and how to negotiate differences. Children get ideas from one another about how to perform certain tasks, how to gain popularity, what to wear or say, and how to act. This society of children marks a transition from a life focused on the family to a life concerned with peers. During middle and late childhood, peers increasingly play an important role. For example, peers play a key role in a child’s self-esteem at this age as any parent who has tried to console a rejected child will tell you. No matter how complimentary and encouraging the parent may be, being rejected by friends can only be remedied by renewed acceptance. Children’s conceptualization of what makes someone a “friend” changes from a more egocentric understanding to one based on mutual trust and commitment. Both Bigelow (1977) and Selman (1980) believe that these changes are linked to advances in cognitive development.

Bigelow and La Gaipa (1975) outline three stages to children’s conceptualization of friendship. In stage one, reward-cost, friendship focuses on mutual activities. Children in early, middle, and late childhood all emphasize similar interests as the main characteristics of a good friend. Stage two, normative expectation focuses on conventional morality; that is, the emphasis is on a friend as someone who is kind and shares with you. Clark and Bittle (1992) found that fifth graders emphasized this in a friend more than third or eighth graders. In the final stage, empathy and understanding, friends are people who are loyal, committed to the relationship, and share intimate information. Clark and Bittle (1992) reported eighth graders emphasized this more in a friend. They also found that as early as fifth grade, girls were starting to include a sharing of secrets, and not betraying confidences as crucial to someone who is a friend.

Selman (1980) outlines five stages of friendship from early childhood through to adulthood:

- Momentary physical interaction, a friend is someone who you are playing with at this point in time. Selman notes that this is typical of children between the ages of three and six. These early friendships are based more on circumstances (e.g., a neighbor) than on genuine similarities.

- One-way assistance, a friend is someone who does nice things for you, such as saving you a seat on the school bus or sharing a toy. However, children in this stage, do not always think about what they are contributing to the relationships. Nonetheless, having a friend is important and children will sometimes put up with a not so nice friend, just to have a friend. Children as young as five and as old as nine may be in this stage.

- Fair-weather cooperation, children are very concerned with fairness and reciprocity, and thus, a friend is someone returns a favor. In this stage, if a child does something Figure 5.21 Source Source 198 nice for a friend there is an expectation that the friend will do something nice for them at the first available opportunity. When this fails to happen, a child may break off the friendship. Selman found that some children as young as seven and as old as twelve are in this stage.

- Intimate and mutual sharing, typically between the ages of eight and fifteen, a friend is someone who you can tell them things you would tell no one else. Children and teens in this stage no longer “keep score” and do things for a friend because they genuinely care for the person. If a friendship dissolves in the stage it is usually due to a violation of trust. However, children in this stage do expect their friend to share similar interests and viewpoints and may take it as a betrayal if a friend likes someone that they do not.

- Autonomous interdependence, a friend is someone who accepts you and that you accept as they are. In this stage children, teens, and adults accept and even appreciate differences between themselves and their friends. They are also not as possessive, so they are less likely to feel threatened if their friends have other relationships or interests. Children are typically twelve or older in this stage.

Peer Relationships: Sociometric assessment measures attraction between members of a group, such as a classroom of students. In sociometric research children are asked to mention the three children they like to play with the most, and those they do not like to play with. The number of times a child is nominated for each of the two categories (like, do not like) is tabulated. Popular children receive many votes in the “like” category, and very few in the “do not like” category. In contrast, rejected children receive more unfavorable votes, and few favorable ones. Controversial children are mentioned frequently in each category, with several children liking them and several children placing them in the do not like category. Neglected children are rarely mentioned in either category, and the average child has a few positive votes with very few negative ones (Asher & Hymel, 1981).

Most children want to be liked and accepted by their friends. Some popular children are nice and have good social skills. These popular-prosocial children tend to do well in school and are cooperative and friendly. Popular-antisocial children may gain popularity by acting tough or spreading rumors about others (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004). Rejected children are sometimes excluded because they are rejected-withdrawn. These children are shy and withdrawn and are easy targets for bullies because they are unlikely to retaliate when belittled (Boulton, 1999). Other rejected children are rejected-aggressive and are ostracized because they are aggressive, loud, and confrontational. The aggressive-rejected children may be acting out of a feeling of insecurity. Unfortunately, their fear of rejection only leads to behavior that brings further rejection from other children. Children who are not accepted are more likely to experience conflict, lack confidence, and have trouble adjusting (Klima & Repetti, 2008; Schwartz, Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 2014).

Long-Term Consequences of Popularity: Childhood popularity researcher Mitch Prinstein has found that likability in childhood leads to positive outcomes throughout one’s life (as cited in Reid, 2017). Adults who were accepted in childhood have stronger marriages and work relationships, earn more money, and have better health outcomes than those who were unpopular. Further, those who were unpopular as children, experienced greater anxiety, depression, substance use, obesity, physical health problems and suicide. Prinstein found that a significant consequence of unpopularity was that children were denied opportunities to build their social skills and negotiate complex interactions, thus contributing to their continued unpopularity. Further, biological effects can occur due to unpopularity, as social rejection can activate genes that lead to an inflammatory response.

Bullying

According to Stopbullying.gov (2016), a federal government website managed by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, bullying is defined as unwanted, aggressive behavior among school aged children that involves a real or perceived power imbalance. Further, the aggressive behavior happens more than once or has the potential to be repeated. There are different types of bullying, including verbal bullying, which is saying or writing mean things, teasing, name calling, taunting, threatening, or making inappropriate sexual comments. Social bullying, also referred to as relational bullying, involves spreading rumors, purposefully excluding someone from a group, or embarrassing someone on purpose. Physical Bullying involves hurting a person’s body or possessions.

A more recent form of bullying is cyberbullying, which involves electronic technology. Examples of cyberbullying include sending mean text messages or emails, creating fake profiles, and posting embarrassing pictures, videos or rumors on social networking sites. Children who experience cyberbullying have a harder time getting away from the behavior because it can occur any time of day and without being in the presence of others. Additional concerns of cyberbullying include that messages and images can be posted anonymously, distributed quickly, and be difficult to trace or delete. Children who are cyberbullied are more likely to: experience in-person bullying, be unwilling to attend school, receive poor grades, use alcohol and drugs, skip school, have lower self-esteem, and have more health problems (Stopbullying.gov, 2016). The National Center for Education Statistics and Bureau of Justice statistics indicate that in 2010-2011, 28% of students in grades 6-12 experienced bullying and 7% experienced cyberbullying. The 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, which monitors six types of health risk behaviors, indicate that 20% of students in grades 9-12 experienced bullying and 15% experienced cyberbullying (Stopbullying.gov, 2016).

Those at risk for bullying: Bullying can happen to anyone, but some students are at an increased risk for being bullied including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered (LGBT) youth, those with disabilities, and those who are socially isolated. Additionally, those who are perceived as different, weak, less popular, overweight, or having low self-esteem, have a higher likelihood of being bullied. 200 Those who are more likely to bully: Bullies are often thought of as having low self-esteem, and then bully others to feel better about themselves. Although this can occur, many bullies in fact have high levels of self-esteem. They possess considerable popularity and social power and have well-connected peer relationships. They do not lack self-esteem, and instead lack empathy for others. They like to dominate or be in charge of others.

Those who are more likely to bully: Bullies are often thought of as having low self-esteem, and then bully others to feel better about themselves. Although this can occur, many bullies in fact have high levels of self-esteem. They possess considerable popularity and social power and have well-connected peer relationships. They do not lack self-esteem, and instead lack empathy for others. They like to dominate or be in charge of others.

Bullied children often do not ask for help: Unfortunately, most children do not let adults know that they are being bullied. Some fear retaliation from the bully, while others are too embarrassed to ask for help. Those who are socially isolated may not know who to ask for help or believe that no one would care or assist them if they did ask for assistance. Consequently, it is important for parents and teacher to know the warning signs that may indicate a child is being bullied. These include: unexplainable injuries, lost or destroyed possessions, changes in eating or sleeping patterns, declining school grades, not wanting to go to school, loss of friends, decreased selfesteem and/or self-destructive behaviors.

Family Life

Family Tasks: One of the ways to assess the quality of family life is to consider the tasks of families. Berger (2014) lists five family functions:

- Providing food, clothing and shelter

- Encouraging learning

- Developing self-esteem

- Nurturing friendships with peers

- Providing harmony and stability

Notice that in addition to providing food, shelter, and clothing, families are responsible for helping the child learn, relate to others, and have a confident sense of self. Hopefully, the family will provide a harmonious and stable environment for living. A good home environment is one in which the child’s physical, cognitive, emotional, and social needs are adequately met. Sometimes families emphasize physical needs but ignore cognitive or emotional needs. Other times, families pay close attention to physical needs and academic requirements but may fail to nurture the child’s friendships with peers or guide the child toward developing healthy relationships. Parents might want to consider how it feels to live in the household as a child. The tasks of families listed above are functions that can be fulfilled in a variety of family types-not just intact, two-parent households.

Parenting Styles: As discussed in the previous chapter, parenting styles affect the relationship parents have with their children. During middle and late childhood, children spend less time with parents and more time with peers, and consequently parents may have to modify their approach to parenting to accommodate the child’s growing independence. The authoritative style, which incorporates reason and engaging in joint decision-making whenever possible may be the most effective approach (Berk, 2007). However, Asian-American, African-American, and Mexican-American parents are more likely than European-Americans to use an authoritarian style of parenting. This authoritarian style of parenting that uses strict discipline and focuses on obedience is also tempered with acceptance and warmth on the part of the parents. Children raised in this manner tend to be confident, successful and happy (Chao, 2001; Stewart & Bond, 2002).

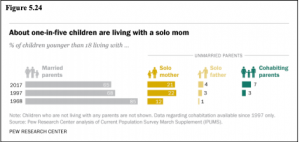

Living Arrangements: Certainly, the living arrangements of children have changed significantly over the years. In 1960, 92% of children resided with married parents, while only 5% had parents who were divorced or separated and 1% resided with parents who had never been married. By 2008, 70% of children resided with married parents, 15% had parent who were divorced or separated, and 14% resided with parents who had never married (Pew Research Center, 2010). In 2017, only 65% of children lived with two married parents, while 32% (24 million children younger than 18) lived with an unmarried parent (Livingston, 2018). Some 3% of children were not living with any parents, according to the U.S. Census Bureau data.

Most children in unmarried parent households in 2017 were living with a solo mother (21%), but a growing share were living with cohabiting parents (7%) or a sole father (4%) (see Figure 5.24). The increase in children living with solo or cohabiting parents was thought to be due to the overall declines in marriage, as well as increases in divorce. Of concern is that living with only one parent was associated with a household’s lower economic situation. Specifically, 30% of solo mothers, 17% of solo fathers, and 16% of families with a cohabitating couple lived in poverty. In contrast, only 8% of married couples lived below the poverty line (Livingston, 2018).

Figure 5.24

Lesbian and Gay Parenting: Research has consistently shown that the children of lesbian and gay parents are as successful as those of heterosexual parents, and consequently efforts are being made to ensure that gay and lesbian couples are provided with the same legal rights as heterosexual couples when adopting children (American Civil Liberties Union, 2016).

Patterson (2013) reviewed more than 25 years of social science research on the development of children raised by lesbian and gay parents and found no evidence of detrimental effects. In fact, research has demonstrated that children of lesbian and gay parents are as well-adjusted overall as those of heterosexual parents. Specifically, research comparing children based on parental sexual orientation has not shown any differences in the development of gender identity, gender role development, or sexual orientation. Additionally, there were no differences between the children of lesbian or gay parents and those of heterosexual parents in separation-individuation, behavior problems, self-concept, locus of control, moral judgment, school adjustment, intelligence, victimization, and substance use. Further, research has consistently found that children and adolescents of gay and lesbian parents report normal social relationships with family members, peers, and other adults. Patterson concluded that there is no evidence to support legal discrimination or policy bias against lesbian and gay parents.

Divorce: Using families in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development, Weaver and Schofield (2015) found that children from divorced families had significantly more behavior problems than those from a matched sample of children from non-divorced families. These problems were evident immediately after the separation and also in early and middle adolescence. An analysis of divorce factors indicated that children exhibited more externalizing behaviors if the family had fewer financial resources before the separation. It was hypothesized that the lower income and lack of educational and community resources contributed to the stress involved in the divorce. Additional factors contributing to children’s behavior problems included a post-divorce home that was less supportive and stimulating, and a mother that was less sensitive and more depressed.

Additional concerns include that the child will grieve the loss of the parent they no longer see as frequently. The child may also grieve about other family members that are no longer available. Very often, divorce means a change in the amount of money coming into the household. Custodial mothers experience a 25% to 50% drop in their family income, and even five years after the divorce they have reached only 94% of their pre-divorce family income (Anderson, 2018). As a result, children experience new constraints on spending or entertainment. School-aged children, especially, may notice that they can no longer have toys, clothing or other items to which they have grown accustomed. Or it may mean that there is less eating out or being able to afford participation in extracurricular activities. The custodial parent may experience stress at not being able to rely on child support payments or having the same level of income as before. This can affect decisions regarding healthcare, vacations, rents, mortgages and other expenditures, and the stress can result in less happiness and relaxation in the home. The parent who has to take on more work may also be less available to the children. Children may also have to adjust to other changes accompanying a divorce. The divorce might mean moving to a new home and changing schools or friends. It might mean leaving a neighborhood that has meant a lot to them as well.

Relationships of adult children of divorce are identified as more problematic than those adults from intact homes. For 25 years, Hetherington and Kelly (2002) followed children of divorce and those whose parents stayed together. The results indicated that 25% of adults whose parents had divorced experienced social, emotional, or psychological problems compared with only 10% of those whose parents remained married. For example, children of divorce have more difficulty forming and sustaining intimate relationships as young adults, are more dissatisfied with their marriage, and consequently more likely to get divorced themselves (Arkowitz & Lilienfeld, 2013). One of the most commonly cited long-term effects of divorce is that children of divorce may have lower levels of education or occupational status (Richter & Lemola, 2017). This may be a consequence of lower income and resources for funding education rather than to divorce per se. In those households where, economic hardship does not occur, there may be no impact on long-term economic status (Drexler, 2005).

According to Arkowitz and Lilienfeld (2013), long-term harm from parental divorce is not inevitable, however, and children can navigate the experience successfully. A variety of factors can positively contribute to the child’s adjustment. For example, children manage better when parents limit conflict, and provide warmth, emotional support and appropriate discipline. Further, children cope better when they reside with a well-functioning parent and have access to social support from peers and other adults. Those at a higher socioeconomic status may fare better because some of the negative consequences of divorce are a result of financial hardship rather than divorce per se (Anderson, 2014; Drexler, 2005). It is important when considering the research findings on the consequences of divorce for children to consider all the factors that can influence the outcome, as some of the negative consequences associated with divorce are due to preexisting problems (Anderson, 2014). Although they may experience more problems than children from non-divorced families, most children of divorce lead happy, well-adjusted lives and develop strong, positive relationships with their custodial parent (Seccombe & Warner, 2004).

Children from single-parent families talk to their mothers more often than children of two-parent families (McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). In a study of college-age respondents, Arditti (1999) found that increasing closeness and a movement toward more democratic parenting styles was experienced. Others have also found that relationships between mothers and children become closer and stronger (Guttman, 1993) and suggest that greater equality and less rigid parenting is beneficial after divorce (Steward, Copeland, Chester, Malley, & Barenbaum, 1997).

Certain characteristics of the child can also facilitate post-divorce adjustment. Specifically, children with an easygoing temperament, who problem-solve well, and seek social support manage better after divorce. A further protective factor for children is intelligence (Weaver & Schofield, 2015). Children with higher IQ scores appear to be buffered from the effects of divorce. Children may be given more opportunity to discover their own abilities and gain independence that fosters self-esteem. If divorce means a reduction in tension, the child may feel relief. Overall, not all children of divorce suffer negative consequences (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Furstenberg and Cherlin (1991) believe that the primary factor influencing the way that children adjust to divorce is the way the custodial parent adjusts to the divorce. If that parent is adjusting well, the children will benefit. This may explain a good deal of the variation we find in children of divorce.

Is cohabitation and remarriage more difficult than divorce for the child? The remarriage of a parent may be a more difficult adjustment for a child than the divorce of a parent (Seccombe & Warner, 2004). Parents and children typically have different ideas of how the stepparent should act. Parents and stepparents are more likely to see the stepparent’s role as that of parent. A more democratic style of parenting may become more authoritarian after a parent remarries. Biological parents are more likely to continue to be involved with their children jointly when neither parent has remarried. They are least likely to jointly be involved if the father has remarried and the mother has not. Cohabitation can be difficult for children to adjust to because cohabiting relationships in the United States tend to be short-lived. About 50 percent last less than 2 years (Brown, 2000). The child who starts a relationship with the parent’s live-in partner may have to sever this relationship later. Even in long-term cohabiting relationships, once it is over, continued contact with the child is rare.

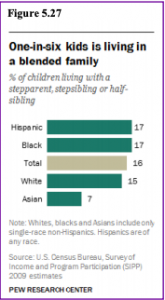

Blended Families: One in six children (16%) live in blended families (Pew Research Center, 2015). As can be seen in Figure 5.27, Hispanic, black and white children are equally likely to be living in a blended family. In contrast, children of Asian descent are more likely to be living with two married parents, often in their first marriage. Blended families are not new. In the 1700-1800s there were many blended families, but they were created because someone died and remarried. Most blended families today are a result of divorce and remarriage, and such origins lead to new considerations. Blended families are different from intact families and more complex in a number of ways that can pose unique challenges to those who seek to form successful blended family relationships (Visher & Visher, 1985). Children may be a part of two households, each with different rules that can be confusing.

Figure 5.27

Members in blended families may not be as sure that others care and may require more demonstrations of affection for reassurance. For example, stepparents expect more gratitude and acknowledgment from the stepchild than they would with a biological child. Stepchildren experience more uncertainty/insecurity in their relationship with the parent and fear the parents will see them as sources of tension. Stepparents may feel guilty for a lack of feelings they may initially have toward their partner’s children. Children who are required to respond to the parent’s new mate as though they were the child’s “real” parent often react with hostility, rebellion, or withdrawal. This occurs especially if there has not been time for the relationship to develop.

References

Aiken, L. R. (1994). Psychological testing and assessment (8th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Alloway, T. P. (2009). Working memory, but not IQ, predicts subsequent learning in children with learning difficulties. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25, 92-98.

Alloway, T. P., Bibile, V., & Lau, G. (2013). Computerized working memory training: Can lead to gains in cognitive skills in students? Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 632-638.

American Civil Liberties Union (2016). Overview of lesbian and gay parenting, adoption and foster care. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/fact-sheet/overview-lesbian-and-gay-parenting-adoption-and-foster-care?redirect=overviewlesbian-and-gay-parenting-adoption-and-foster-care

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Speech-Language and Hearing Association. (2016). Voice disorders. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/PracticePortal/Clinical-Topics/Voice-Disorders/ Arditti, J. A. (1999). Rethinking relationships between divorced mothers and their children: Capitalizing on family strengths. Family Relations, 48, 109-119.

Anderson, J. (2018). The impact of family structure on the health of children: Effects of divorce. The Linacre Quarterly 81(4), 378–387.

Arkowicz, H., & Lilienfeld. (2013). Is divorce bad for children? Scientific American Mind, 24(1), 68-69. Figure 5.27 206

Asher, S. R., & Hymel, S. (1981). Children’s social competence in peer relations: Sociometric and behavioral assessment. In J. K. Wine & M. D. Smye (Eds.), Social competence (pp. 125-157). New York: Guilford Press.

Banaschewski, T., Becker, K., Döpfner, M., Holtmann, M., Rösler, M., & Romanos, M. (2017). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. A current overview. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 114, 149-159.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Barnett, N. P., Smoll, F. L., & Smith, R. E. (1992). Effects of enhancing coach-athlete relationships on youth sport attrition. The Sport Psychologist, 6, 111-127.

Barbaresi, W. J., Colligan, R. C., Weaver, A. L., Voigt, R. G., Killian, J. M., & Katusic, S. K. (2013). Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: A prospective study. Pediatrics, 131, 637–644.

Barkley, R. A. (2006). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Barkley, R. A., Fischer, M., Smallish, L., & Fletcher, K. (2002). The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 279–289.

Beaulieu, C. (2004). Intercultural study of personal space: A case study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(4), 794-805.

Berk, L. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Berger, K. S. (2014). The developing person: Through the life span. NY: Worth Publishers.

Bigelow, B. J. (1977). Children’s friendship expectations: A cognitive developmental study. Child Development, 48, 246–253.

Bigelow, B. J., & La Gaipa, J. J. (1975). Children’s written descriptions of friendship: A multidimensional analysis. Developmental Psychology, 11(6), 857-858.

Binet, A., Simon, T., & Town, C. H. (1915). A method of measuring the development of the intelligence of young children (3rd ed.) Chicago, IL: Chicago Medical Book.

Bink, M. L., & Marsh, R. L. (2000). Cognitive regularities in creative activity. Review of General Psychology, 4(1), 59–78.

Bjorklund, D. F. (2005). Children’s thinking: Developmental function and individual differences (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Black, J. A., Park, M., Gregson, J. (2015). Child obesity cut-offs as derived from parental perceptions: Cross-sectional questionnaire. British Journal of General Practice, 65, e234-e239.

Boulton, M. J. (1999). Concurrent and longitudinal relations between children’s playground behavior and social preference, victimization, and bullying. Child Development, 70, 944-954.

Brody, N. (2003). Construct validation of the Sternberg Triarchic Abilities Test: Comment and reanalysis. Intelligence, 31(4), 319–329.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univeristy Press.

Brown, S. L. (2000). Union transitions among cohabitors: The significance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 833-846. 207

Bruning, R. H., Schraw, G. J., Norby, M. M., & Ronning, R. R. (2004). Cognitive psychology and instruction. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Burt, S. A. (2009). Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: A meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 608–637.

Carlson, N. (2013). Physiology of behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Carlson, S. M., & Zelazo, P. D., & Faja, S. (2013). Executive function. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology, Vol. 1: Body and mind (pp. 706-743). New York: Oxford University Press

Camarota, S. A., & Zeigler, K. (2015). One in five U. S. residents speaks foreign language at home. Retrieved from https://cis.org/sites/default/files/camarota-language-15.pdf

Cazden, C. (2001). Classroom discourse, (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heineman Publishers.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2000). 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_11/sr11_246.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010, November 12). Increasing prevalence of parent reported attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder among children, United States, 2003–2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59(44), 1439–1443.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Birth defects. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/downsyndrome/data.html

Chao, R. (2001). Extending research on the consequences of parenting styles for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Development, 72, 1832-1843.

Cillesen, A. H., & Mayeaux, L. (2004). From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development, 75, 147-163.

Clark, M. L., & Bittle, M. L. (1992). Friendship expectations and the evaluation of present friendships in middle childhood and early adolescence. Child Study Journal, 22, 115–135.

Clay, R. A. (2013). Psychologists are using research-backed behavioral interventions that effectively treat children with ADHD. Monitor on Psychology, 44(2), 45-47.

Cohen, E. (2004). Teaching cooperative learning: The challenge for teacher education. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Colangelo, N., & Assouline, S. (2009). Acceleration: Meeting the academic and social needs of students. In T. Balchin, B. Hymer, & D. J. Matthews (Eds.), The Routledge international companion to gifted education (pp. 194–202). New York, NY: Routledge.

Cowan, R., & Powell, D. (2014). The contributions of domain-general and numerical factors to third-grade arithmetic skills and mathematical learning disability. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106, 214-229.

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Davidson, T. L. (2014). Do impaired memory and body weight regulation originate in childhood with diet-induced hippocampal dysfunction? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 99(5), 971-972.

Davidson, T. L., Hargrave, S. L., Swithers, S. E., Sample, C. H., Fu, X., Kinzig, K. P., & Zheng, W. (2013). Inter-relationships among diet, obesity, and hippocampal-dependent cognitive function. Neuroscience, 253, 110-122.

de Ribaupierre, A. (2002). Working memory and attentional processes across the lifespan. In P. Graf & N. Ohta (Eds.), Lifespan of development of human memory (pp. 59-80). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. 208

Discover Esports. (2017). What are esports? Retrieved from https://discoveresports.com/what-are-esports/

Doolen, J., Alpert, P. T. and Miller, S. K. (2009), Parental disconnect between perceived and actual weight status of children: A metasynthesis of the current research. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 21, 160–166. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00382.x

Drexler, P. (2005). Raising boys without men. Emmaus, PA: Rodale.

Dutton, E., van der Linden, D., Lynn, R. (2016). The negative Flynn effect: A systematic literature review. Intelligence, 59, 163- 169. Ennis, R. H. (1987). A taxonomy of critical thinking dispositions and abilities. In J. Baron & R. Sternberg (Eds.), Teaching thinking skills: Theory and practice (pp. 9-26). New York: Freeman.

Ericsson, K. (1998). The scientific study of expert levels of performance: General implications for optimal learning and creativity. High Ability Studies, 9(1), 75–100.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. NY: Norton & Company.

Flynn, J. R. (1999). Searching for justice: The discovery of IQ gains over time. American Psychologist, 54(1), 5–20.

Francis, N. (2006). The development of secondary discourse ability and metalinguistic awareness in second language learners. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 16, 37-47.

Fraser-Thomas, J. L., Côté, J., & Deakin, J. (2005). Youth sport programs: An avenue to foster positive youth development. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 10, 19-40.

Furnham, A., & Bachtiar, V. (2008). Personality and intelligence as predictors of creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(7), 613–617.

Furstenberg, F. F., & Cherlin, A. J. (1991). Divided families: What happens to children when parents part. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gizer, I. R., Ficks, C., & Waldman, I. D. (2009). Candidate gene studies of ADHD: A meta-analytic review. Human Genetics, 126, 51–90.

Gottfredson, L. S. (1997). Mainstream science on intelligence: An editorial with 52 signatories, history and bibliography. Intelligence, 24(1), 13–23.

Gottfredson, L. S. (2003). Dissecting practical intelligence theory: Its claims and evidence. Intelligence, 31(4), 343–397.

Greenspan, S., Loughlin, G., & Black, R. S. (2001). Credulity and gullibility in people with developmental disorders: A framework for future research. In L. M. Glidden (Ed.), Internationalreview ofresearch in mental retardation (Vol. 24, pp. 101–135). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Guttmann, J. (1993). Divorce in psychosocial perspective: Theory and research. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834.

Hales, C.M., Carroll, M.D., Fryar, C.D., & Ogden, C.L. (2017). Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 209

Halpern, D. F. (1992). Sex differences in cognitive abilities (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hansen, L., Umeda, Y., & McKinney, M. (2002). Savings in the relearning of second language vocabulary: The effects of time and proficiency. Language Learning, 52, 653-663.

Hartup, W. W. (1983). Adolescents and their friends. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 60, 3-22.

Hennessey, B. A., & Amabile, T. M. (2010). Creativity. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 569–598.

Hetherington, E. M., & Kelly, J. (2002). For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York: W.W. Norton.

Horvat, E. M. (2004). Moments of social inclusion and exclusion: Race, class, and cultural capital in family-school relationships. In A. Lareau (Author) & J. H. Ballantine & J. Z. Spade (Eds.), Schools and society: A sociological approach to education (2nd ed., pp. 276-286). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Hoza, B., Mrug, S., Gerdes, A. C., Hinshaw, S. P., Bukowski, W. M., Gold, J. A., . . . Arnold, L. E. (2005). What aspects of peer relationships are impaired in children with ADHD? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 411–423.

Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. New York: Basic Books.

Jaffee, S., & Hyde, J. S. (2000). Gender differences in moral orientation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 703– 726.

Jimenez, R., Garcia, G., & Pearson. D. (1995). Three children, two languages, and strategic reading: Case studies in bilingual/monolingual reading. American Educational Research Journal, 32 (1), 67-97. Johnson, D., & Johnson, R. (1998). Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning, (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Johnson, M. (2005). Developmental neuroscience, psychophysiology, and genetics. In M. Bornstein & M. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (5th ed., pp. 187-222).

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Johnson, W., Carothers, A., & Deary, I. J. (2009). A role for the X chromosome in sex differences in variability in general intelligence? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(6), 598–611.

Kail, R. V., McBride-Chang, C., Ferrer, E., Cho, J.R., & Shu, H. (2013). Cultural differences in the development of processing speed. Developmental Science, 16, 476-483.

Katz, D. L. (2015). Oblivobesity: Looking over the overweight that parents keep overlooking. Childhood Obesity, 11(3), 225- 226.

Klein, R. G., Mannuzza, S., Olazagasti, M. A. R., Roizen, E., Hutchison, J. A., Lashua, E. C., & Castellanos, F. X. (2012). Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 1295–1303.

Klima, T., & Repetti, R. L. (2008). Children’s peer relations and their psychological adjustment: Differences between close friends and the larger peer group. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54, 151-178.

Kohlberg, L. (1963). The development of children’s orientations toward a moral order: Sequence in the development of moral thought. Vita Humana, 16, 11-36.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development: Essays on moral development (Vol. 2, p. 200). San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

Kohnert, K., Yim, D., Nett, K., Kan, P., & Duran, L. (2005). Intervention with linguistically diverse preschool children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 36, 251-263.

Lally, M. J., & Valentine-French, S. J. (2018). Introduction to Psychology [Adapted from Charles Stangor, Introduction to Psychology] Grayslake, IL: College of Lake County. 210

Liang, J., Matheson, B., Kaye, W., & Boutelle, K. (2014). Neurocognitive correlates of obesity and obesity-related behaviors in children and adolescents. International Journal of Obesity, 38(4), 494-506

Linnet, K. M., Dalsgaard, S., Obel, C., Wisborg, K., Henriksen, T. B., Rodriquez, A., . . . Jarvelin, M. R.(2003). Maternal lifestyle factors in pregnancy risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated behaviors: A review of current evidence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1028–1040.

Livingston, G. (2018). About one-third of U.S. children are living with an unmarried parent. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/27/about-one-third-of-u-s-children-are-living-with-an-unmarriedparent/

Loe, I. M., & Feldman, H. M. (2007). Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 643–654.

Lofquist, D. (2011). Same-sex households. Current population reports, ACSBR/10-03. U.S. CensusBureau, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/acsbr10-03.pdf

Lu, S. (2016). Obesity and the growing brain. Monitor on Psychology, 47(6), 40-43.

Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2006). Study of mathematically precocious youth after 35 years: Uncovering antecedents for the development of math-science expertise. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(4), 316–345.

Macbeth, D. (2003). Hugh Mehan’s Learning Lessons reconsidered: On the differences between naturalistic and critical analysis of classroom discourse. American Educational Research Journal, 40 (1), 239-280.

Markant, J. C., & Thomas, K. M. (2013). Postnatal brain development. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Marshal, M. P., & Molina, B. S. G. (2006). Antisocial behaviors moderate the deviant peer pathway to substance use in children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 216–226.

McCann, D., Barrett, A., Cooper, A., Crumpler, D., Dalen, L., Grimshaw, K., . . . Stevenson, J. (2007). Food additives and hyperactive behaviour in 3-year-old and 8/9-year-old children in the community: A randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet, 370(9598), 1560–1567.

McGuine, T. A. (2016). The association of sports specialization and history of lower extremity injury in high school athletes. Medical Science in Sports and Exercise, 45 (supplement 5), 866.

McLanahan, S., & Sandefur, G. D. (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Medline Plus. (2016a). Phonological disorder. National Institute of Mental Health: U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001541.htm

Medline Plus. (2016b). Speech and communication disorders. National Institute of Mental Health: U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/speechandcommunicationdisorders.html

Medline Plus. (2016c). Stuttering. National Institute of Mental Health: U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001427.htm

Miller, P. H. (2000). How best to utilize a deficiency? Child Development, 71, 1013-1017.

Minami, M. (2002). Culture-specific language styles: The development of oral narrative and literacy. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

National Center for Learning Disabilities. (2017). The state of LD: Understanding the 1 in 5. Retrieved from https://www.ncld.org/archives/blog/the-state-of-ld-understanding-the-1-in-5

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2016). Dyslexia information page. Retrieved from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Dyslexia-Information-Page 211

National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders. (2016). Stuttering. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/stuttering

Neisser, U. (1997). Rising scores on intelligence tests. American Scientist, 85, 440-447.

Neisser, U. (1998). The rising curve. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Oude Luttikhuis, H., Stolk, R. and Sauer, P. (2010), How do parents of 4- to 5-year-old children perceive the weight of their children? Acta Pædiatrica, 99, 263–267. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01576.x

Patterson, C. J. (2013). Children of lesbian and gay parents: Psychology, law, and Policy. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1, 27-34.

Pettit, G. S., Clawson, M. A., Dodge, K. A., & Bates, J. E. (1996). Stability and change in peer-rejected status: The role of child behavior, parenting, and family ecology. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 42(2), 267-294.

Pew Research Center. (2010). New family types. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/11/18/vi-new-familytypes/

Pew Research Center. (2015). Parenting in America. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/wpcontent/uploads/sites/3/2015/12/2015-12-17_parenting-in-america_FINAL.pdf

Plante, I., De la Sablonnière, R., Aronson, J. M., & Théorêt, M. (2013). Gender stereotype endorsement and achievement-related outcomes: The role of competence beliefs and task values. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(3), 225-235.

PreBler, A., Krajewski, K., & Hasselhorn, M. (2013). Working memory capacity in preschool children contributes to the acquisition of school relevant precursor skills. Learning and Individual Differences, 23, 138-144.

Public Law 93-112, 87 Stat. 394 (Sept. 26, 1973). Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

Public Law 101-336, 104 Stat. 327 (July 26, 1990). Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

Public Law 108-446, 118 Stat. 2647 (December 3, 2004). Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

Reid, S. (2017). 4 questions for Mitch Prinstein. Monitor on Psychology, 48(8), 31-32.

Rest, J. (1979). Development in judging moral issues. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Retelsdorf, J., Asbrock, F., & Schwartz, K. (2015). “Michael can’t read!” teachers’ gender stereotypes and boys’ reading selfconcept. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 186-194.

Richter, D, & Lemola, S. (2017). Growing up with a single mother and life satisfaction in adulthood: A test of mediating and moderating factors. PLOS ONE 12(6): e0179639. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0179639

Rogers, R., Malancharuvil-Berkes, E., Mosely, M., Hui, D., & O’Garro, G. (2005). Critical discourse analysis in education: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 75 (3), 365-416.

Rogoff, B. (2003). The culture of human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rolls, E. (2000). Memory systems in the brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 599-630.

Ross, H. S., & Lollis, S. P. (1989). A social relations analysis of toddler peer relations. Child Development, 60, 1082-1091.

Rubin, R. (1980). Children’s friendships. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sabo, D., & Veliz, P. (2008). Go out and play: Youth sports in America. East Meadow, NY: Women’s Sports Foundation 212

Sarafrazi, N., Hughes, J. P., & Borrud, L. (2014). Perception of weight status in U.S. children and adolescents aged 8-15 years, 2005-2012. NCHS Data Brief, 158, 1-8.

Schneider, W., Kron-Sperl, V., & Hünnerkopf, M. (2009). The development of young children’s memory strategies: Evidence from the Würzburg Longitudinal Memory Study. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 6, 70-99.

Schneider, W., & Pressley, M. (1997). Memory development between 2 and 20. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Schwartz, D., Lansford, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2014). Peer victimization during middle childhood as a lead indicator of internalizing problems and diagnostic outcomes in late adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44, 393-404.

Seagoe, M. V. (1975). Terman and the gifted. Los Altos, CA: William Kaufmann.

Seccombe, K., & Warner, R. L. (2004). Marriages and families: Relationships in social context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Seifert, K. (2011). Educational psychology. Houston, TX: Rice University.

Selman, Robert L. (1980). The growth of interpersonal understanding. London: Academic Press.

Siegler, R. S. (1992). The other Alfred Binet. Developmental Psychology, 28(2), 179–190.

Simonton, D. K. (1992). The social context of career success and course for 2,026 scientists and inventors. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(4), 452–463.

Simonton, D. K. (2000). Creativity: Cognitive, personal, developmental, and social aspects. American Psychologist, 55(1), 151– 158.

Sodian, B., & Schneider, W. (1999). Memory strategy development: Gradual increase, sudden insight or roller coaster? In F. E. Weinert & W. Schneider (Eds.), Individual development from 3 to 12: Findings from the Munich Longitudinal Study (pp. 61-77). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Sourander, A., Sucksdorff, M., Chudal, R, Surcel, H., Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S., Gyllenberg, D., Cheslack-Postava, K., & Brown, A. (2019). Prenatal cotinine levels and ADHD among offspring. Pediatrics, 143(3), e20183144.

Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (SPARC, 2013). What is the status of youth coach training in the U.S.? University of Florida. Retrieved from https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/files/content/upload/Project%20Play%20Research%20Brief%20Coach ing%20Education%20–%20FINAL.pdf

Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (SPARC, 2016). State of play 2016: Trends and developments. The Aspen Institute. Retrieved from https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/state-play-2016-trends-developments/

Spreen, O., Rissser, A., & Edgell, D. (1995). Developmental neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (1985). Beyond IQ: A triarchic theory of human intelligence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (2003). Contemporary theories of intelligence. In W. M. Reynolds & G. E. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Educational psychology (Vol. 7, pp. 23–45). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Sternberg, R. J., Wagner, R. K., & Okagaki, L. (1993). Practical intelligence: The nature and role of tacit knowledge in work and at school. In J. M. Puckett & H. W. Reese (Eds.), Mechanisms of everyday cognition (pp. 205–227). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Stewart, A. J., Copeland, Chester, Malley, & Barenbaum. (1997). Separating together: How divorce transforms families. New York: Guilford Press.

Stewart, S. M. & Bond, M. H. (2002), A critical look at parenting research from the mainstream: Problems uncovered while adapting Western research to non-Western cultures. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20, 379–392. doi:10.1348/026151002320620389 213

Stopbullying.gov. (2018). Preventing weight-based bullying. Retrieved from https://www.stopbullying.gov/blog/2018/11/05/preventing-weight-based-bullying.html

Swanson, J. M., Kinsbourne, M., Nigg, J., Lamphear, B., Stefanatos, G. A., Volkow, N., …& Wadhwa, P. D. (2007). Etiologic subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: brain imaging, molecular genetic and environmental factors and the dopamine hypothesis. Neuropsychological Review, 17(1), 39-59.

Tarasova, I. V., Volf, N. V., & Razoumnikova, O. M. (2010). Parameters of cortical interactions in subjects with high and low levels of verbal creativity. Human Physiology, 36(1), 80–85.

Terman, L. M., & Oden, M. H. (1959). Genetic studies of genius: The gifted group at mid-life (Vol. 5). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Thakur, G. A., Sengupta, S. M., Grizenko, N., Schmitz, N., Page, V., & Joober, R. (2013). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and ADHD: A comprehensive clinical and neurocognitive characterization. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 15, 149– 157.

Tharp, R. & Gallimore, R. (1989). Rousing minds to life. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, A., Molina, B. S. G., Pelham, W., & Gnagy, E. M. (2007). Risky driving in adolescents and young adults with childhood ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 745–759.

Torres-Guzman, M. (1998). Language culture, and literacy in Puerto Rican communities. In B. Perez (Ed.), Sociocultural contexts of language and literacy. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Treffert, D. A., & Wallace, G. L. (2004). Islands of genius. Scientific American, 14–23. Retrieved from http://gordonresearch.com/articles_autism/SciAm-Islands_of_Genius.pdf

Tse, L. (2001). Why don’t they learn English? New York: Teachers’ College Press.

Turiel, E. (1998). The development of morality. In W. Damon (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Socialization (5th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 863–932). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

United States Department of Education. (2017). Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Retrieved from https://www.ed.gov/essa?src=ft United States Youth Soccer. (2012).

US youth soccer at a glance. Retrieved from http://www.usyouthsoccer.org/media_kit/ataglance/

Vakil, E., Blachstein, H., Sheinman, M., & Greenstein, Y. (2009). Developmental changes in attention tests norms: Implications for the structure of attention. Child Neuropsychology, 15, 21-39.

van der Molen, M., & Molenaar, P. (1994). Cognitive psychophysiology: A window to cognitive development and brain maturation. In G. Dawson & K. Fischer (Eds.), Human behavior and the developing brain. New York: Guilford.

Visher, E. B., & Visher, J. S. (1985). Stepfamilies are different. Journal of Family Therapy, 7(1), 9-18.

Volkow N. D., Fowler J. S., Logan J., Alexoff D., Zhu W., Telang F., . . . Apelskog-Torres K. (2009). Effects of modafinil on dopamine and dopamine transporters in the male human brain: Clinical implications. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301, 1148–1154.

Wagner, R., & Sternberg, R. (1985). Practical intelligence in real-world pursuits: The role of tacit knowledge. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(2), 436–458.

Watkins, C. E., Campbell, V. L., Nieberding, R., & Hallmark, R. (1995). Contemporary practice of psychological assessment by clinical psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 26(1), 54–60.

Weaver, J. M., & Schofield, T. J. (2015). Mediation and moderation of divorce effects on children’s behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(1), 39-48. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/fam0000043 214

Weir, K. (2019). Family-based behavioral treatment is key to addressing childhood obesity. Monitor on Pscyhology, 50(4), 31- 35.

Weisberg, R. (2006). Creativity: Understanding innovation in problem solving, science, invention, and the arts. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Wilens, E., Fararone, S.V., Biederman, J., & Gunawardene, S. (2003). Does the treatment of Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with stimulants contribute to use/abuse? Pediatrics, 111(1), 97-109.

Wolraich, M. L., Wilson, D. B., & White, J. W. (1995). The effect of sugar on behavior or cognition in children. Journal of the American Medical Association, 274, 1617–1621.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 5 from Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective Second Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 unported license.