Chapter 11: Cognitive Development in Infancy & Toddlerhood

Chapter 11 Learning Objectives

- Compare the Piagetian concepts of schema, assimilation, and accommodation

- List and describe the six substages of sensorimotor intelligence

- Describe the characteristics of infant memory

- Describe components and developmental progression of language

- Identify and compare the theories of language

Piaget and the Sensorimotor Stage

Schema, Assimilation, and Accommodation

Piaget believed that we are continuously trying to maintain cognitive equilibrium, or a balance, in what we see and what we know (Piaget, 1954). Children have much more of a challenge in maintaining this balance because they are constantly being confronted with new situations, new words, new objects, etc. All this new information needs to be organized, and a framework for organizing information is referred to as a schema. Children develop schemata through the processes of assimilation and accommodation.

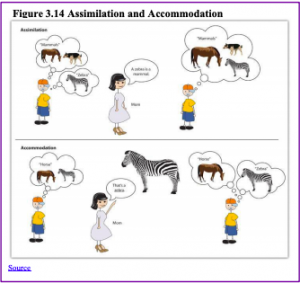

Figure 3.14

When faced with something new, a child may demonstrate assimilation, which is fitting the new information into an existing schema, such as calling all animals with four legs “doggies” because he or she knows the word doggie. Instead of assimilating the information, the child may demonstrate accommodation, which is expanding the framework of knowledge to accommodate the new situation and thus learning a new word to more accurately name the animal. For example, recognizing that a horse is different from a zebra means the child has accommodated, and now the child has both a zebra schema and a horse schema. Even as adults we continue to try and “make sense” of new situations by determining whether they fit into our old way of thinking (assimilation) or whether we need to modify our thoughts (accommodation). According to the Piagetian perspective, infants learn about the world primarily through their senses and motor abilities (Harris, 2005). These basic motor and sensory abilities provide the foundation for the cognitive skills that will emerge during the subsequent stages of cognitive development. The first stage of cognitive development is referred to as the sensorimotor stage and it occurs through six substages. Table 3.2 identifies the ages typically associated with each substage.

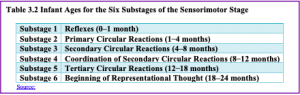

Table 3.2

Substage 1: Reflexes. Newborns learn about their world through the use of their reflexes, such as when sucking, reaching, and grasping. Eventually the use of these reflexes becomes more deliberate and purposeful.

Substage 2: Primary Circular Reactions. During these next 3 months, the infant begins to actively involve his or her own body in some form of repeated activity. An infant may accidentally engage in a behavior and find it interesting such as making a vocalization. This interest motivates trying to do it again and helps the infant learn a new behavior that originally occurred by chance. The behavior is identified as circular because of the repetition, and as primary because it centers on the infant’s own body.

Substage 3: Secondary Circular Reactions. The infant begins to interact with objects in the environment. At first the infant interacts with objects (e.g., a crib mobile) accidentally, but then these contacts with the objects are deliberate and become a repeated activity. The infant becomes more and more actively engaged in the outside world and takes delight in being able to make things happen. Repeated motion brings particular interest as, for example, the infant is able to bang two lids together from the cupboard when seated on the kitchen floor.

Substage 4: Coordination of Secondary Circular Reactions. The infant combines these basic reflexes and simple behaviors and uses planning and coordination to achieve a specific goal. Now the infant can engage in behaviors that others perform and anticipate upcoming events. Perhaps because of continued maturation of the prefrontal cortex, the infant becomes capable of having a thought and carrying out a planned, goal-directed activity. For example, an infant sees a toy car under the kitchen table and then crawls, reaches, and grabs the toy. The infant is coordinating both internal and external activities to achieve a planned goal.

Substage 5: Tertiary Circular Reactions. The toddler is considered a “little scientist” and begins exploring the world in a trial-and-error manner, using both motor skills and planning abilities. For example, the child might throw her ball down the stairs to see what happens. The toddler’s active engagement in experimentation helps them learn about their world.

Substage 6: Beginning of Representational Thought. The sensorimotor period ends with the appearance of symbolic or representational thought. The toddler now has a basic understanding that objects can be used as symbols. Additionally, the child is able to solve problems using mental strategies, to remember something heard days before and repeat it, and to engage in pretend play. This initial movement from a “hands-on” approach to knowing about the world to the more mental world of substage six marks the transition to preoperational thought.

Development of Object Permanence

A critical milestone during the sensorimotor period is the development of object permanence. Object permanence is the understanding that even if something is out of sight, it still exists (Bogartz, Shinskey, & Schilling, 2000). According to Piaget, young infants do not remember an object after it has been removed from sight. Piaget studied infants’reactions when a toy was first shown to them and then hidden under a blanket. Infants who had already developed object permanence would reach for the hidden toy, indicating that they knew it still existed, whereas infants who had not developed object permanence would appear confused. Piaget emphasizes this construct because it was an objective way for children to demonstrate that they can mentally represent their world. Children have typically acquired this milestone by 8 months. Once toddlers have mastered object permanence, they enjoy games like hide and seek, and they realize that when someone leaves the room they will come back. Toddlers also point to pictures in books and look at inappropriate places when you ask them to find objects.

In Piaget’s view, around the same time children develop object permanence, they also begin to exhibit stranger anxiety, which is a fear of unfamiliar people (Crain, 2005). Babies may demonstrate this by crying and turning away from a stranger, by clinging to a caregiver, or by attempting to reach their arms toward familiar faces, such as parents. Stranger anxiety results when a child is unable to assimilate the stranger into an existing schema; therefore, she cannot predict what her experience with that stranger will be like, which results in a fear response.

Critique of Piaget

Piaget thought that children’s ability to understand objects, such as learning that a rattle makes a noise when shaken, was a cognitive skill that develops slowly as a child matures and interacts with the environment. Today, developmental psychologists think Piaget was incorrect. Researchers have found that even very young children understand objects and how they work long before they have experience with those objects (Baillargeon, 1987; Baillargeon, Li, Gertner, & Wu, 2011). For example, Piaget believed that infants did not fully master object permanence until substage 5 of the sensorimotor period (Thomas, 1979). However, infants seem to be able to recognize that objects have permanence at much younger ages. Diamond (1985) found that infants show earlier knowledge if the waiting period is shorter. At age 6 months, they retrieved the hidden object if their wait for retrieving the object is no longer than 2 seconds, and at 7 months if the wait is no longer than 4 seconds.

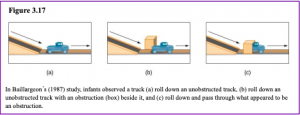

Others have found that children as young as 3 months old have demonstrated knowledge of the properties of objects that they had only viewed and did not have prior experience with. In one study, 3-month-old infants were shown a truck rolling down a track and behind a screen. The box, which appeared solid but was actually hollow, was placed next to the track. The truck rolled past the box as would be expected. Then the box was placed on the track to block the path of the truck. When the truck was rolled down the track this time, it continued unimpeded. The infants spent significantly more time looking at this impossible event (Figure 3.17). Baillargeon (1987) concluded that they knew solid objects cannot pass through each other. Baillargeon’s findings suggest that very young children have an understanding of objects and how they work, which Piaget (1954) would have said is beyond their cognitive abilities due to their limited experiences in the world.

Figure 3.17

Infant Memory

Memory requires a certain degree of brain maturation, so it should not be surprising that infant memory is rather fleeting and fragile. As a result, older children and adults experience infantile amnesia, the inability to recall memories from the first few years of life. Several hypotheses have been proposed for this amnesia. From the biological perspective, it has been suggested that infantile amnesia is due to the immaturity of the infant brain, especially those areas that are crucial to the formation of autobiographical memory, such as the hippocampus. From the cognitive perspective, it has been suggested that the lack of linguistic skills of babies and toddlers limit their ability to mentally represent events; thereby, reducing their ability to encode memory. Moreover, even if infants do form such early memories, older children and adults may not be able to access them because they may be employing very different, more linguistically based, retrieval cues than infants used when forming the memory. Finally, social theorists argue that episodic memories of personal experiences may hinge on an understanding of “self”, something that is clearly lacking in infants and young toddlers.

However, in a series of clever studies Carolyn Rovee-Collier and her colleagues have demonstrated that infants can remember events from their life, even if these memories are shortlived. Three-month-old infants were taught that they could make a mobile hung over their crib shake by kicking their legs. The infants were placed in their crib, on their backs. A ribbon was tied to one foot and the other end to a mobile. At first infants made random movements, but then came to realize that by kicking they could make the mobile shake. After two 9-minute sessions with the mobile, the mobile was removed. One week later the mobile was reintroduced to one group of infants and most of the babies immediately started kicking their legs, indicating that they remembered their prior experience with the mobile. The second group of infants was shown on the mobile two weeks later, and the babies made only random movements. The memory had faded (Rovee-Collier, 1987; Giles & Rovee-Collier, 2011). Rovee-Collier and Hayne (1987) found that 3-month-olds could remember the mobile after two weeks if they were shown the mobile and watched it move, even though they were not tied to it. This reminder helped most infants to remember the connection between their kicking and the movement of the mobile. Like many researchers of infant memory, Rovee-Collier (1990) found infant memory to be very context-dependent. In other words, the sessions with the mobile and the later retrieval sessions had to be conducted under very similar circumstances or else the babies would not remember their prior experiences with the mobile. For instance, if the first mobile had had yellow blocks with blue letters, but at the later retrieval session the blocks were blue with yellow letters, the babies would not kick. Infants older than 6 months of age can retain information for longer periods of time; they also need less reminding to retrieve information in memory.

Infants older than 6 months of age can retain information for longer periods of time; they also need less reminding to retrieve information in memory. Studies of deferred imitation, that is, the imitation of actions after a time delay, can occur as early as six months of age (Campanella & Rovee-Collier, 2005), but only if infants are allowed to practice the behavior they were shown. By 12 months of age, infants no longer need to practice the behavior in order to retain memory for four weeks (Klein & Meltzoff, 1999).

Language

Our vast intelligence also allows us to have language, a system of communication that uses symbols in a regular way to create meaning. Language gives us the ability to communicate our intelligence to others by talking, reading, and writing. Although other species have at least some ability to communicate, none of them have language. There are many components of language that will now be reviewed.

Components of Language

Phoneme: A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound that makes a meaningful difference in a language. The word “bit” has three phonemes. In spoken languages, phonemes are produced by the positions and movements of the vocal tract, including our lips, teeth, tongue, vocal cords, and throat, whereas in sign language phonemes are defined by the shapes and movement of the hands.

There are hundreds of unique phonemes that can be made by human speakers, but most languages only use a small subset of the possibilities. English contains about 45 phonemes, whereas other languages have as few as 15 and others more than 60. The Hawaiian language contains fewer phonemes as it includes only 5 vowels (a, e, i, o, and u) and 7 consonants (h, k, l, m, n, p, and w).

Infants are born able to detect all phonemes, but they lose their ability to do so as they get older; by 10 months of age, a child’s ability to recognize phonemes becomes very similar to that of the adult speakers of the native language. Phonemes that were initially differentiated come to be treated as equivalent (Werker & Tees, 2002).

Morpheme: Whereas phonemes are the smallest units of sound in language, a morpheme is a string of one or more phonemes that makes up the smallest units of meaning in a language. Some morphemes are prefixes and suffixes used to modify other words. For example, the syllable “re-” as in “rewrite” or “repay” means “to do again,” and the suffix “-est” as in “happiest” or “coolest” means “to the maximum.”

Semantics: Semantics refers to the set of rules we use to obtain meaning from morphemes. For example, adding “ed” to the end of a verb makes it past tense.

Syntax: Syntax is the set of rules of a language by which we construct sentences. Each language has a different syntax. The syntax of the English language requires that each sentence has a noun and a verb, each of which may be modified by adjectives and adverbs. Some syntaxes make use of the order in which words appear. For example, in English, the meaning of the sentence “The man bites the dog” is different from “The dog bites the man.”

Pragmatics: The social side of language is expressed through pragmatics, or how we communicate effectively and appropriately with others. Examples of pragmatics include turn taking, staying on topic, volume and tone of voice, and appropriate eye contact.

Lastly, words do not possess fixed meanings but change their interpretation as a function of the context in which they are spoken. We use contextual information, the information surrounding language, to help us interpret it. Examples of contextual information include our knowledge and nonverbal expressions, such as facial expressions, postures, and gestures. Misunderstandings can easily arise if people are not attentive to contextual information or if some of it is missing, such as it may be in newspaper headlines or in text messages.

Language Developmental Progression

An important aspect of cognitive development is language acquisition. The order in which children learn language structures is consistent across children and cultures (Hatch, 1983). Starting before birth, babies begin to develop language and communication skills. At birth, babies recognize their mother’s voice and can discriminate between the language(s) spoken by their mothers and foreign languages, and they show preferences for faces that are moving in synchrony with audible language (Blossom & Morgan, 2006; Pickens et al., 1994; Spelke & Cortelyou, 1981).

Do newborns communicate? Of course, they do. They do not, however, communicate with the use of oral language. Instead, they communicate their thoughts and needs with body posture (being relaxed or still), gestures, cries, and facial expressions. A person who spends adequate time with an infant can learn which cries indicate pain and which ones indicate hunger, discomfort, or frustration.

Intentional Vocalizations: In terms of producing spoken language, babies begin to coo almost immediately. Cooing is a one-syllable combination of a consonant and a vowel sound (e.g., coo or ba). Interestingly, babies replicate sounds from their own languages. A baby whose parents speak French will coo in a different tone than a baby whose parents speak Spanish or Urdu. These gurgling, musical vocalizations can serve as a source of entertainment to an infant who has been laid down for a nap or seated in a carrier on a car ride. Cooing serves as practice for vocalization, as well as the infant hears the sound of his or her own voice and tries to repeat sounds that are entertaining. Infants also begin to learn the pace and pause of conversation as they alternate their vocalization with that of someone else and then take their turn again when the other person’s vocalization has stopped.

At about four to six months of age, infants begin making even more elaborate vocalizations that include the sounds required for any language. Guttural sounds, clicks, consonants, and vowel sounds stand ready to equip the child with the ability to repeat whatever sounds are characteristic of the language heard. Eventually, these sounds will no longer be used as the infant grows more accustomed to a particular language.

At about 7 months, infants begin babbling, engaging in intentional vocalizations that lack specific meaning and comprise a consonant-vowel repeated sequence, such as ma-ma-ma, da-da-da. Children babble as practice in creating specific sounds, and by the time they are a 1-year-old, the babbling uses primarily the sounds of the language that they are learning (de Boysson- Bardies, Sagart, & Durand, 1984). These vocalizations have a conversational tone that sounds meaningful even though it is not. Babbling also helps children understand the social, communicative function of language. Children who are exposed to sign language babble in sign by making hand movements that represent real language (Petitto & Marentette, 1991).

Gesturing: Children communicate information through gesturing long before they speak, and there is some evidence that gesture usage predicts subsequent language development (Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005). Deaf babies also use gestures to communicate wants, reactions, and feelings. Because gesturing seems to be easier than vocalization for some toddlers, sign language is sometimes taught to enhance one’s ability to communicate by making use of the ease of gesturing. The rhythm and pattern of language are used when deaf babies sign, just as it is when hearing babies babble.

Understanding: At around ten months of age, the infant can understand more than he or she can say, which is referred to as receptive language. You may have experienced this phenomenon as well if you have ever tried to learn a second language. You may have been able to follow a conversation more easily than contribute to it. One of the first words that children understand is their own name, usually by about 6 months, followed by commonly used words like “bottle,” “mama,” and “doggie” by 10 to 12 months (Mandel, Jusczyk, & Pisoni, 1995).

Infants shake their head “no” around 6–9 months, and they respond to verbal requests to do things like “wave bye-bye” or “blow a kiss” around 9–12 months. Children also use contextual information, particularly the cues that parents provide, to help them learn the language. Children learn that people are usually referring to things that they are looking at when they are speaking (Baldwin, 1993), and that that the speaker’s emotional expressions are related to the content of their speech.

Holophrastic Speech: Children begin using their first words at about 12 or 13 months of age and may use partial words to convey thoughts at even younger ages. These one-word expressions are referred to as holophrasic speech. For example, the child may say “ju” for the word “juice” and use this sound when referring to a bottle. The listener must interpret the meaning of the holophrase, and when this is someone who has spent time with the child, interpretation is not too difficult. But, someone who has not been around the child will have trouble knowing what is meant. Imagine the parent who to a friend exclaims, “Ezra’s talking all the time now!” The friend hears only “ju da ga” to which the parent explains means, “I want some milk when I go with Daddy.”

Language Errors: The early utterances of children contain many errors, for instance, confusing /b/ and /d/, or /c/ and /z/. The words children create are often simplified, in part because they are not yet able to make the more complex sounds of the real language (Dobrich & Scarborough, 1992). Children may say “keekee” for kitty, “nana” for banana, and “vesketti” for spaghetti because it is easier. Often these early words are accompanied by gestures that may also be easier to produce than the words themselves. Children’s pronunciations become increasingly accurate between 1 and 3 years, but some problems may persist until school age.

A child who learns that a word stands for an object may initially think that the word can be used for only that particular object, which is referred to as underextension. Only the family’s Irish Setter is a “doggie”, for example. More often, however, a child may think that a label applies to all objects that are similar to the original object, which is called overextension. For example, all animals become “doggies”. The first error is often the result of children learning the meaning of a word in a specific context, while the second language error is a function of the child’s smaller vocabulary.

First words and cultural influences: If the child is using English, first words tend to be nouns. The child labels objects such as a cup, ball, or other items that they regularly interact with. In a verb-friendly language such as Chinese, however, children may learn more verbs. This may also be due to the different emphasis given to objects based on culture. Chinese children may be taught to notice action and relationships between objects, while children from the United States may be taught to name an object and its qualities (color, texture, size, etc.). These differences can be seen when comparing interpretations of art by older students from China and the United States (Imai et al., 2008).

Two-word sentences and telegraphic (text message) speech: By the time they become toddlers, children have a vocabulary of about 50-200 words and begin putting those words together in telegraphic speech, such as “baby bye-bye” or “doggie pretty”. Words needed to convey messages are used, but the articles and other parts of speech necessary for grammatical correctness are not yet used. These expressions sound like a telegraph, or perhaps a better analogy today would be that they read like a text message. Telegraphic speech/text message speech occurs when unnecessary words are not used. “Give baby ball” is used rather than “Give the baby the ball.”

Infant-directed Speech: Why is a horse a “horsie”? Have you ever wondered why adults tend to use “baby talk” or that sing-song type of intonation and exaggeration used when talking to children? This represents a universal tendency and is known as infant-directed speech. It involves exaggerating the vowel and consonant sounds, using a high-pitched voice, and delivering the phrase with great facial expression (Clark, 2009). Why is this done? Infants are frequently more attuned to the tone of voice of the person speaking than to the content of the words themselves and are aware of the target of speech. Werker, Pegg, and McLeod (1994) found that infants listened longer to a woman who was speaking to a baby than to a woman who was speaking to another adult. Adults may use this form of speech in order to clearly articulate the sounds of a word so that the child can hear the sounds involved. It may also be because when this type of speech is used, the infant pays more attention to the speaker and this sets up a pattern of interaction in which the speaker and listener are in tune with one another.

Theories of Language Development

Psychological theories of language learning differ in terms of the importance they place on nature and nurture. Remember that we are a product of both nature and nurture. Researchers now believe that language acquisition is partially inborn and partially learned through our interactions with our linguistic environment (Gleitman & Newport, 1995; Stork & Widdowson, 1974). First to be discussed are the biological theories, including nativist, brain areas, and critical periods. Next, learning theory and social pragmatics will be presented.

Nativism: The linguist Noam Chomsky is a believer in the natural approach to language, arguing that human brains contain a language acquisition device (LAD) that includes a universal grammar that underlies all human language (Chomsky, 1965, 1972). According to this approach, each of the many languages spoken around the world (there are between 6,000 and 8,000) is an individual example of the same underlying set of procedures that are hardwired into human brains. Chomsky’s account proposes that children are born with a knowledge of general rules of syntax that determine how sentences are constructed. Language develops as long as the infant is exposed to it. No teaching, training, or reinforcement is required for language to develop as proposed by Skinner.

Chomsky differentiates between the deep structure of an idea; that is, how the idea is represented in the fundamental universal grammar that is common to all languages, and the surface structure of the idea or how it is expressed in any one language. Once we hear or express a thought in surface structure, we generally forget exactly how it happened. At the end of a lecture, you will remember a lot of the deep structure (i.e., the ideas expressed by the instructor), but you cannot reproduce the surface structure (the exact words that the instructor used to communicate the ideas).

Although there is general agreement among psychologists that babies are genetically programmed to learn language, there is still debate about Chomsky’s idea that there is a universal grammar that can account for all language learning. Evans and Levinson (2009) surveyed the world’s languages and found that none of the presumed underlying features of the language acquisition device were entirely universal. In their search, they found languages that did not have noun or verb phrases, that did not have tenses (e.g., past, present, future), and even some that did not have nouns or verbs at all, even though a basic assumption of a universal grammar is that all languages should share these features.

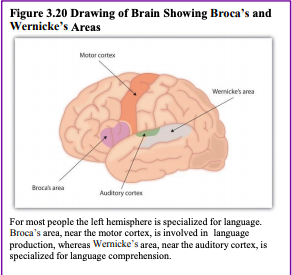

Brain Areas for Language: For the 90% of people who are right-handed, language is stored and controlled by the left cerebral cortex, although for some left-handers this pattern is reversed. These differences can easily be seen in the results of neuroimaging studies that show that listening to and producing language creates greater activity in the left hemisphere than in the right. Broca’s area, an area in front of the left hemisphere near the motor cortex, is responsible for language production (Figure 3.20).

Figure 3.20 Drawing of Brain Showing Broca’s and Wernicke’s Area

This area was first localized in the 1860s by the French physician Paul Broca, who studied patients with lesions to various parts of the brain. Wernicke’s area, an area of the brain next to the auditory cortex, is responsible for language comprehension.

Is there a critical period for learning a language? Psychologists believe there is a critical period, a time in which learning can easily occur, for language. This critical period appears to be between infancy and puberty (Lenneberg, 1967; Penfield & Roberts, 1959), but isolating the exact timeline has been elusive. Children who are not exposed to language early in their lives will likely never grasp the grammatical and communication nuances of language. Case studies, including Victor the “Wild Child,” who has abandoned as a baby in 18th century France and not discovered until he was 12, and Genie, a child whose parents kept her locked away from 18 months until 13 years of age, are two examples of children who were deprived of language. Both children made some progress in socialization after they were rescued, but neither of them ever developed a working understanding of language (Rymer, 1993). Yet, such case studies are fraught with many confounds. How much did the years of social isolation and malnutrition contribute to their problems in language development?

A better test for the notion of critical periods for language is found in studies of children with hearing loss. Several studies show that the earlier children are diagnosed with hearing impairment and receive treatment, the better the child’s long-term language development. For instance, Stika et al. (2015) reported that when children’s hearing loss was identified during newborn screening, and subsequently addressed, the majority showed normal language development when later tested at 12-18 months. Fitzpatrick, Crawford, Ni, and Durieux-Smith (2011) reported that early language intervention in children who were moderately to severely hard of hearing, demonstrated normal outcomes in language proficiency by 4 to 5 years of age. Tomblin et al. (2015) reported that children who were fit with hearing aids by 6 months of age showed good levels of language development by age 2. Those whose hearing was not corrected until after 18 months showed lower language performance, even in the early preschool years. However, this study did reveal that those whose hearing was corrected by toddlerhood had greatly improved language skills by age 6. The research with hearing impaired children reveals that this critical period for language development is not exclusive to infancy, and that the brain is still receptive to language development in early childhood. Fortunately, it is has become routine to screen hearing in newborns, because when hearing loss is not treated early, it can delay spoken language, literacy, and impact children’s social skills (Moeller & Tomblin, 2015).

Learning Theory: Perhaps the most straightforward explanation of language development is that it occurs through the principles of learning, including association and reinforcement (Skinner, 1953). Additionally, Bandura (1977) described the importance of observation and imitation of others in learning language. There must be at least some truth to the idea that language is learned through environmental interactions or nurture. Children learn the language that they hear spoken around them rather than some other language. Also supporting this idea is the gradual improvement of language skills with time. It seems that children modify their language through imitation and reinforcement, such as parental praise and being understood. For example, when a two-year-old child asks for juice, he might say, “me juice,” to which his mother might respond by giving him a cup of apple juice.

Figure 3.22 Three Theorists who provide explanations for language development

However, language cannot be entirely learned. For one, children learn words too fast for them to be learned through reinforcement. Between the ages of 18 months and 5 years, children learn up to 10 new words every day (Anglin, 1993). More importantly, language is more generative than it is imitative. Language is not a predefined set of ideas and sentences that we choose when we need them, but rather a system of rules and procedures that allows us to create an infinite number of statements, thoughts, and ideas, including those that have never previously occurred. When a child says that she “swimmed” in the pool, for instance, she is showing generativity. No adult speaker of English would ever say “swimmed,” yet it is easily generated from the normal system of producing language.

Other evidence that refutes the idea that all language is learned through experience comes from the observation that children may learn languages better than they ever hear them. Deaf children whose parents do not communicate using ASL very well nevertheless are able to learn it perfectly on their own and may even make up their own language if they need to (Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1998). A group of deaf children in a school in Nicaragua, whose teachers could not sign, invented a way to communicate through made-up signs (Senghas, Senghas, & Pyers, 2005). The development of this new Nicaraguan Sign Language has continued and changed as new generations of students have come to the school and started using the language. Although the original system was not a real language, it is becoming closer and closer every year, showing the development of a new language in modern times.

Social pragmatics: Another view emphasizes the very social nature of human language. Language from this view is not only a cognitive skill but also a social one. A language is a tool humans use to communicate, connect to, influence and inform others. Most of all, language comes out of a need to cooperate. The social nature of language has been demonstrated by a number of studies that have shown that children use several pre-linguistic skills (such as pointing and other gestures) to communicate not only their own needs but what others may need. So, a child watching her mother search for an object may point to the object to help her mother find it. Eighteen-month to 30-month-olds have been shown to make linguistic repairs when it is clear that another person does not understand them (Grosse, Behne, Carpenter & Tomasello, 2010). Grosse et al. (2010) found that even when the child was given the desired object if there had been any misunderstanding along the way (such as a delay in being handed the object, or the experimenter calling the object by the wrong name), children would make linguistic repairs. This would suggest that children are using language not only as a means of achieving some material goal, but to make themselves understood in the mind of another person.

References

Ainsworth, M. (1979). Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist, 34(10), 932-937.

Ainsworth, M., Blehar, M., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Akimoto, S. A., & Sanbinmatsu, D. M. (1999). Differences in self-effacing behavior between European and Japanese Americans: Effect on competence evaluations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 159-177.

American Optometric Association. (2019). Infant vision: Birth to 24 months of age. Retrieved from https://www.aoa.org/patients-and-public/good-vision-throughout-life/childrens-vision/infant-vision-birth-to-24- months-of-age

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5).

Washington, DC: Author.

Anglin, J. M. (1993). Vocabulary development: A morphological analysis. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58 10), v–165.

Aslin, R. N. (1981). Development of smooth pursuit in human infants. In D. F. Fisher, R. A. Monty, & J. W. Senders (Eds.), Eye movements: Cognition and visual perception (pp. 31– 51). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Atkinson, J., & Braddick, O. (2003). Neurobiological models of normal and abnormal visual development. In M. de Haan & M. H. Johnson (Eds.), The cognitive neuroscience of development (pp. 43– 71). Hove: Psychology Press.

Baillargeon, R. (1987. Object permanence in 3 ½ and 4 ½ year-old infants. Developmental Psychology, 22, 655-664. Baillargeon, R., Li, J., Gertner, Y, & Wu, D. (2011). How do infants reason about physical events? In U. Goswami (Ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development. MA: John Wiley.

Balaban, M. T. & Reisenauer, C. D. (2013). Sensory development. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 1144-1147). New, York: Sage Publications.

Baldwin, D. A. (1993). Early referential understanding: Infants’ ability to recognize referential acts for what they are. Developmental Psychology, 29(5), 832–843.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bartrip J, Morton J, & De Schonen S. (2001). Responses to mother’s face in 3-week to 5-month-old infants. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19, 219–232

Berk, L. E. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Berne, S. A. (2006). The primitive reflexes: Considerations in the infant. Optometry & Vision Development, 37(3), 139-145. Bloem, M. (2007). The 2006 WHO child growth standards. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 334(7596), 705–706. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39155.658843.BE

Blossom, M., & Morgan, J. L. (2006). Does the face say what the mouth says? A study of infants’ sensitivity to visual prosody. In the 30th annual Boston University conference on language development, Somerville, MA.

Bogartz, R. S., Shinskey, J. L., & Schilling, T. (2000). Object permanence in five-and-a-half month old infants. Infancy, 1(4), 403-428.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. London: Hogarth Press. Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Bradshaw, D. (1986). Immediate and prolonged effectiveness of negative emotion expressions in inhibiting infants’ actions (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley.

Braungart-Rieker, J. M., Hill-Soderlund, A. L., &Karrass, J. (2010). Fear, anger reactivity trajectories from 4 to 16 months: The roles of temperament, regulation, and maternal sensitivity. Developmental Psychology, 46, 791-804.

Bushnell, I. W. R. (2001) Mother’s face recognition in newborn infants: Learning and memory. Infant Child Development, 10, 67-94.

Bushnell, I. W. R., Sai, F., Mullin, J. T. (1989). Neonatal recognition of mother’s face. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 7, 3-15.

Bruer, J. T. (1999). The myth of the first three years: A new understanding of early brain development and lifelong learning. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Campanella, J., & Rovee-Collier, C. (2005). Latent learning and deferred imitation at 3 months. Infancy, 7(3), 243-262. Carlson, N. (2014). Foundations of behavioral neuroscience (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Carpenter, R., McGarvey, C., Mitchell, E. A., Tappin, D. M., Vennemann, M. M., Smuk, M., & Carpenter, J. R. (2013). Bed sharing when parents do not smoke: Is there a risk of SIDS? An individual level analysis of five major case–control studies. BMJ Open, 3:e002299. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002299

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Breastfeeding facts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/facts.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Sudden unexpected infant death and sudden infant death syndrome. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/sids/data.htm

Cheour-Luhtanen, M., Alho. K., Kujala, T., Reinikainen, K., Renlund, M., Aaltonen, O., … & Näätänen R. (1995). Mismatch negativity indicates vowel discrimination in newborns. Hearing Research, 82, 53–58.

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1996). Temperament: Theory and practice. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Chi, J. G., Dooling, E. C., & Gilles, F. H. (1977). Left-right asymmetries of the temporal speech areas of the human fetus. Archives of Neurology, 34, 346–8.

Chien S. (2011). No more top-heavy bias: Infants and adults prefer upright faces but not top-heavy geometric or face-like patterns. Journal of Vision, 11(6):1–14.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Chomsky, N. (1972). Language and mind. NY: Harcourt Brace.

Clark, E. V. (2009). What shapes children’s language? Child-directed speech and the process of acquisition. In V. C. M. Gathercole (Ed.), Routes to language: Essays in honor of Melissa Bowerman. NY: Psychology Press.

Clark, L. A., Kochanska, G., & Ready, R. (2000). Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 274–285.

Clemson University Cooperative Extension. (2014). Introducing solid foods to infants. Retrieved from http://www.clemson.edu/extension/hgic/food/nutrition/nutrition/life_stages/hgic4102.html

Cole, P. M., Armstrong, L. M., & Pemberton, C. K. (2010). The role of language in the development of emotional regulation. In S. D. Calkins & M. A. Bell (Eds.). Child development at intersection of emotion and cognition (pp. 59-77). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Colvin, J.D., Collie-Akers, V., Schunn, C., & Moon, R.Y. (2014). Sleep environment risks for younger and older infants. Pediatrics Online. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2014/07/09/peds. 2014-0401.full.pdf

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). NJ: Pearson.

de Boysson-Bardies, B., Sagart, L., & Durand, C. (1984). Discernible differences in the babbling of infants according to target language. Journal of Child Language, 11(1), 1–15.

DeCasper, A. J., & Fifer, W. P. (1980). Of human bonding: Newborns prefer their mother’s voices. Science, 208, 1174-1176. DeCasper, A. J., & Spence, M. J. (1986). Prenatal maternal speech influences newborns’ perception of speech sounds. Infant Behavior and Development, 9, 133-150.

Diamond, A. (1985). Development of the ability to use recall to guide actions, as indicated by infants’ performance on AB. Child Development, 56, 868-883.

Dobrich, W., & Scarborough, H. S. (1992). Phonological characteristics of words young children try to say. Journal of Child Language, 19(3), 597–616.

Dubois, J., Hertz-Pannier, L., Cachia, A., Mangin, J. F., Le Bihan, D., & Dehaene-Lambertz, G. (2009). Structural asymmetries in the infant language and sensori-motor networks. Cerebral Cortex, 19, 414–423.

Eisenberg, A., Murkoff, H. E., & Hathaway, S. E. (1989). What to expect the first year. New York: Workman Publishing.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Guthrie, I.K., Murphy, B.C., & Reiser, M. (1999). Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development, 70, 513-534.

Eisenberg, N., Hofer, C., Spinrad, T., Gershoff, E., Valiente, C., Losoya, S. L., Zhou, Q., Cumberland, A., Liew, J., Reiser, M., & Maxon, E. (2008). Understanding parent-adolescent conflict discussions: Concurrent and across-time prediction from youths’ dispositions and parenting. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73, (Serial No. 290, No. 2), 1-160.

El-Dib, M., Massaro, A. N., Glass, P., & Aly, H. (2012). Neurobehavioral assessment as a predictor of neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants. Journal of Perinatology, 32, 299-303.

Eliot, L. (1999). What’s going on in there? New York: Bantam. Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. NY: Norton & Company.

Evans, N., & Levinson, S. C. (2009). The myth of language universals: Language diversity and its importance for cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 32(5), 429–448.

Farroni, T., Johnson, M.H. Menon, E., Zulian, L. Faraguna, D., Csibra, G. (2005). Newborns’ preference for face-relevant stimuli: Effects of contrast polarity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(47), 17245-17250.

Fergusson, D. M., & Woodward, L. J. (1999). Breastfeeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 13, 144-157.

Fitzpatrick, E.M., Crawford, L., Ni, A., & Durieux-Smith, A. (2011). A descriptive analysis of language and speech skills in 4-to- 5-yr-old children with hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 32(2), 605-616.

Freud, S. (1938). An outline of psychoanalysis. London: Hogarth.

Galler J. R., & Ramsey F. (1989). A follow-up study of the influence of early malnutrition on development: Behavior at home and at school. American Academy of Child and Adolescence Psychiatry, 28 (2), 254-61.

Galler, J. R., Ramsey, F. C., Morely, D. S., Archer, E., & Salt, P. (1990). The long-term effects of early kwashiorkor compared with marasmus. IV. Performance on the national high school entrance examination. Pediatric Research, 28(3), 235- 239.

Galler, J. R., Ramsey, F. C., Salt, P. & Archer, E. (1987). The long-term effect of early kwashiorkor compared with marasmus. III. Fine motor skills. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology Nutrition, 6, 855-859.

Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37.

Giles, A., & Rovee-Collier, C. (2011). Infant long-term memory for associations formed during mere exposure. Infant Behavior and Development, 34 (2), 327-338.

Gillath, O., Shaver, P. R., Baek, J. M., & Chun, D. S. (2008). Genetic correlates of adult attachment style. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1396–1405.

Gleitman, L. R., & Newport, E. L. (1995). The invention of language by children: Environmental and biological influences on the acquisition of language. An Invitation to Cognitive Science, 1, 1-24.

Goldin-Meadow, S., & Mylander, C. (1998). Spontaneous sign systems created by deaf children in two cultures. Nature, 391(6664), 279–281.

Grosse, G., Behne, T., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2010). Infants communicate in order to be understood. Developmental Psychology, 46(6), 1710-1722.

Gunderson, E. P., Hurston, S. R., Ning, X., Lo, J. C., Crites, Y., Walton, D…. & Quesenberry, C. P. Jr. (2015). Lactation and progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. American Journal of Medicine, 163, 889-898. Doi: 10.7326/m 15-0807.

Hainline L. (1978). Developmental changes in visual scanning of face and nonface patterns by infants. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 25, 90–115.

Hamer, R. (2016). The visual world of infants. Scientific American, 104, 98-101. Harlow, H. F. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 673-685.

Harris, Y. R. (2005). Cognitive development. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 276-281). New, York: Sage Publications.

Hart, S., & Carrington, H. (2002). Jealousy in 6-month-old infants. Infancy, 3(3), 395-402.

Hatch, E. M. (1983). Psycholinguistics: A second language perspective. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers. Hertenstein, M. J., & Campos, J. J. (2004). The retention effects of an adult’s emotional displays on infant behavior. Child Development, 75(2), 595–613.

Holland, D., Chang, L., Ernst, T., Curan, M Dale, A. (2014). Structural growth trajectories and rates of change in the first 3 months of infant brain development. JAMA Neurology, 71(10), 1266-1274.

Huttenlocher, P. R., & Dabholkar, A. S. (1997). Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 387(2), 167-178.

Hyde, J. S., Else-Quest, N. M., & Goldsmith, H. H. (2004). Children’s temperament and behavior problems predict their employed mothers’ work functioning. Child Development, 75, 580–594.

Hyvärinen, L., Walthes, R., Jacob, N., Nottingham Chaplin, K., & Leonhardt, M. (2014). Current understanding of what infants see. Current Opthalmological Report, 2, 142-149. doi:10.1007/s40135-014-0056-2

Imai, M., Li, L., Haryu, E., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Shigematsu, J. (2008). Novel noun and verb learning in Chinese, English, and Japanese children: Universality and language-specificity in novel noun and verb learning. Child Development, 79, 979-1000.

Islami, F., Liu, Y., Jemal, A., Zhou, J., Weiderpass, E., Colditz, G…Weiss, M. (2015). Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 26, 2398-2407.

Iverson, J. M., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2005). Gesture paves the way for language development. Psychological science, 16(5), 367-371.

Jarrett, C. (2015). Great myths of the brain. West Sussex, UK: Wiley.

Johnson, M. H., & deHaan, M. (2015). Developmental cognitive neuroscience: An introduction. Chichester, West Sussex: UK, Wiley & Sons

Jusczyk, P.W., Cutler, A., & Redanz, N.J. (1993). Infants’ preference for the predominant stress patterns of English words. Child Development, 64, 675–687.

Karlson, E.W., Mandl, L.A., Hankison, S. E., & Grodstein, F. (2004). Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis & Rheumatism, 50 (11), 3458-3467.

Kasprian, G., Langs, G., Brugger, P. C., Bittner, M., Weber, M., Arantes, M., & Prayer, D. (2011). The prenatal origin of hemispheric asymmetry: an in utero neuroimaging study. Cerebral Cortex, 21, 1076–1083.

Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Zalewski, M. (2011). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 251–301. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0093-4

Klein, P. J., & Meltzoff, A. N. (1999). Long-term memory, forgetting, and deferred imitation in 12-month-old infants. Developmental Science, 2(1), 102-113.

Klinnert, M. D., Campos, J. J., & Sorce, J. F. (1983). Emotions as behavior regulators: Social referencing in infancy. In R. Plutchik & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotion: Theory, research, and experience (pp. 57–86). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Kolb, B., & Fantie, B. (1989). Development of the child’s brain and behavior. In C. R. Reynolds & E. Fletcher-Janzen (Eds.),

Handbook of clinical child neuropsychology (pp. 17–39). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Kolb, B. & Whishaw, I. Q. (2011). An introduction to brain and behavior (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishers.

Kopp, C. B. (2011). Development in the early years: Socialization, motor development, and consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 165-187.

Latham, M. C. (1997). Human nutrition in the developing world. Rome, IT: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Lavelli, M., & Fogel, A. (2005). Developmental changes in the relationships between infant attention and emotion during early face-to-face communications: The 2 month transition. Developmental Psychology, 41, 265-280.

Lenneberg, E. (1967). Biological foundations of language. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

LeVine, R. A., Dixon, S., LeVine, S., Richman, A., Leiderman, P. H., Keefer, C. H., & Brazelton, T. B. (1994). Child care and culture: Lessons from Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, M., & Brooks, J. (1978). Self-knowledge and emotional development. In M. Lewis & L. A. Rosenblum (Eds.), Genesis of behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 205-226). New York: Plenum Press.

Lewis, T. L., Maurer, D., & Milewski, A. (1979). The development of nasal detection in young infants. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science Supplement, 19, 271.

Li, Y., & Ding, Y. (2017). Human visual development. In Y. Liu., & W. Chen (Eds.), Pediatric lens diseases (pp. 11-20). Singapore: Springer.

Los Angles County Department of Public Health. (2019). Breastfeeding vs. formula feeding. Retrieved from http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/LAmoms/lessons/Breastfeeding/6_BreastfeedingvsFormulaFeeding.pdf

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment inthe Preschool Years (pp.121– 160).Chicago,IL: UniversityofChicagoPress.

Mandel, D. R., Jusczyk, P. W., & Pisoni, D. B. (1995). Infants’ recognition of the sound patterns of their own names. Psychological Science, 6(5), 314–317.

Mayberry, R. I., Lock, E., & Kazmi, H. (2002). Development: Linguistic ability and early language exposure. Nature, 417(6884), 38.

Moeller, M.P., & Tomblin, J.B. (2015). An introduction to the outcomes of children with hearing loss study. Ear and Hearing, 36 Suppl (0-1), 4S-13S

Morelli, G., Rogoff, B., Oppenheim, D., & Goldsmith, D. (1992). Cultural variations in infants’ sleeping arrangements: Questions of independence. Developmental Psychology, 28, 604-613.

Nelson, E. A., Schiefenhoevel, W., & Haimerl, F. (2000). Child care practices in nonindustrialized societies. Pediatrics, 105, e75.

O’Connor, T. G., Marvin, R. S., Rotter, M., Olrich, J. T., Britner, P. A., & The English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. (2003). Child-parent attachment following early institutional deprivation. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 19- 38.

Papousek, M. (2007). Communication in early infancy: An arena of intersubjective learning. Infant Behavior and Development, 30, 258-266.

Pearson Education. (2016). Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Third Edition. New York: Pearson. Retrieved from http://www.pearsonclinical.com/childhood/products/100000123/bayley-scales-of-infant-and-toddler-development- third-edition-bayley-iii.html#tab-details

Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (1959). Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Petitto, L. A., & Marentette, P. F. (1991). Babbling in the manual mode: Evidence for the ontogeny of language. Science, 251(5000), 1493–1496.

Phelps, B. J. (2005). Habituation. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 597-600). New York: Sage Publications.

Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books.

Pickens, J., Field, T., Nawrocki, T., Martinez, A., Soutullo, D., & Gonzalez, J. (1994). Full-term and preterm infants’ perception of face-voice synchrony. Infant Behavior and Development, 17(4), 447-455.

Porter, R. H., Makin, J. W., Davis, L. M., Christensen, K. (1992). Responsiveness of infants to olfactory cues from lactating females. Infant Behavior and Development, 15, 85-93.

Redondo, C. M., Gago-Dominguez, M., Ponte, S. M., Castelo, M. E., Jiang, X., Garcia, A.A… Castelao, J. E. (2012). Breast feeding, parity and breast cancer subtypes in a Spanish cohort. PLoS One, 7(7): e40543 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.00040543

Richardson, B. D. (1980). Malnutrition and nutritional anthropometry. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 26(3), 80-84. Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (2006). Temperament. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.). Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 99-116). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Rothbart, M. K., Posner, M. I. & Kieras, J. (2006). Temperament, attention, and the development of self-regulation. In M. McCartney & D. Phillips (Eds.) Blackwell handbook of early childhood development (pp. 3338-357). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Pott, M., Miyake, K., & Morelli, G. (2010). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55, 1093-1104.

Rovee-Collier, C. (1987). Learning and memory in infancy. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Handbook of infant development, (2nd, ed., pp. 98-148). New York: Wiley.

Rovee-Collier, C. (1990). The “memory system” of prelinguistic infants. Annuals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 608, 517-542. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-66231990.tb48908.

Rovee-Collier, C., & Hayne, H. (1987). Reactivation of infant memory: Implications for cognitive development. In H. W. Reese (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior. (Vol. 20, pp. 185-238). London, UK: Academic Press.

Rymer, R. (1993). Genie: A scientific tragedy. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Salkind, N. J. (2005). Encyclopedia of human development. New York: Sage Publications.

Schwarz, E. B., Brown, J. S., Creasman, J. M. Stuebe, A., McClure, C. K., Van Den Eeden, S. K., & Thom, D. (2010). Lactation and maternal risk of type-2 diabetes: A population-based study. American Journal of Medicine, 123, 863.e1-863.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.03.016.

Seifer, R., Schiller, M., Sameroff, A., Resnick, S., & Riordan, K. (1996). Attachment, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament during the first year of life. Developmental Psychology, 32, 12-25.

Sen, M. G., Yonas, A., & Knill, D. C. (2001). Development of infants’ sensitivity to surface contour information for spatial layout. Perception, 30, 167-176.

Senghas, R. J., Senghas, A., & Pyers, J. E. (2005). The emergence of Nicaraguan Sign Language: Questions of development, acquisition, and evolution. In S. T. Parker, J. Langer, & C. Milbrath (Eds.), Biology and knowledge revisited: From neurogenesis to psychogenesis (pp. 287–306). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Shaffer, D. R. (1985). Developmental psychology: Theory, research, and applications. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Inc. Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. NY: Free Press.

Sorce, J. F., Emde, J. J., Campos, J. J., & Klinnert, M. D. (1985). Maternal emotional signaling: Its effect on the visual cliff behavior of 1-year-olds. Developmental Psychology, 21, 195–200.

Spelke, E. S., & Cortelyou, A. (1981). Perceptual aspects of social knowing: Looking and listening in infancy. Infant social cognition, 61-84.

Springer, S. P. & Deutsch, G. (1993). Left brain, right brain (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman.

Stika, C.J., Eisenberg, L.S., Johnson, K.C. Henning, S.C., Colson, B.G., Ganguly, D.H., & DesJardin, J.L. (2015). Developmental outcomes of early-identified children who are hard of hearing at 12 to 18 months of age. Early Human Development, 9(1), 47-55.

Stork, F. & Widdowson, J. (1974). Learning about Linguistics. London: Hutchinson.

Thomas, R. M. (1979). Comparing theories of child development. Santa Barbara, CA: Wadsworth.

Thompson, R. A. (2006). The development of the person. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th Ed.). New York: Wiley.

Thompson, R. A., & Goodvin, R. (2007). Taming the tempest in the teapot. In C. A. Brownell & C. B. Kopp (Eds.). Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations (pp. 320-342). New York: Guilford.

Thompson, R. A., Winer, A. C., & Goodvin, R. (2010). The individual child: Temperament, emotion, self, and personality. In M. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (6th ed., pp. 423–464). New York, NY: Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis.

Titus-Ernstoff, L., Rees, J. R., Terry, K. L., & Cramer, D. W. (2010). Breast-feeding the last-born child and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control, 21(2), 201-207. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9450-8

Tomblin, J. B., Harrison, M., Ambrose, S. E., Walker, E. A., Oleson, J. J., & Moeller, M. P. (2015). Language outcomes in young children with mild to severe hearing loss. Ear and hearing, 36 Suppl 1(0 1), 76S–91S.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2015). Levels and trends in child mortality: Report 2015. United Nations Children’s Fund. New York: NY.

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Women’s Health. (2011). Your guide to breast feeding. Washington D.C.

United States National Library of Medicine. (2016). Circumcision. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/circumcision.html

Van den Boom, D. C. (1994). The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Development, 65, 1457–1477.

Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Sagi, A. (1999). Cross-cultural patterns of attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 713-734). New York: Guilford.

Webb, S. J., Monk, C. S., & Nelson, C. A. (2001). Mechanisms of postnatal neurobiological development: Implications for human development. Developmental Neuropsychology, 19, 147-171.

Weekes-Shackelford, V. A. & Shackelford, T. K. (2005). Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human development (pp. 1238-1239). New York: Sage Publications.

Werker, J. F., Pegg, J. E., & McLeod, P. J. (1994). A cross-language investigation of infant preference for infant-directed communication. Infant Behavior and Development, 17, 323-333.

Werker, J. F., & Tees, R. C. (2002). Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behavior and Development, 25, 121-133.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 3 from Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective Second Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 unported license.