Chapter 30: Psychosocial Development in Late Adulthood

Chapter 30 Learning Objectives

- Explain the stereotypes of those in late adulthood and how it impacts their lives

- Summarize Erikson’s eight psychosocial tasks of integrity vs. despair

- Explain how self-concept and self-esteem affect those in late adulthood

- Identify sources of despair and regret

- Describe paths to integrity, including the activity, socioemotional selectivity, and convoy theories

- Describe the continuation of generativity in late adulthood

- Describe the relationships those in late adulthood have with their children and other family members

- Describe singlehood, marriage, widowhood, divorce, and remarriage in late adulthood

- Describe the different types of residential living in late adulthood

- Describe friendships in late life

- Explain concerns experienced by those in late adulthood, such as abuse and mental health issues

- Explain how those in late adulthood use strategies to compensate for losses

Ageism

Stereotypes of people in late adulthood lead many to assume that aging automatically brings poor physical health and mental decline. These stereotypes are reflected in everyday conversations, the media, and even in greeting cards (Overstreet, 2006). Age is not revered in the United States, and so laughing about getting older in birthday cards is one way to get relief. The negative attitudes people have about those in late adulthood are examples of ageism or prejudice based on age. The term ageism was first used in 1969, and according to Nelson (2016), ageism remains one of the most institutionalized forms of prejudice today.

Nelson (2016) reviewed the research on ageism and concluded that when older individuals believed their culture’s negative stereotypes about those who are old, their memory and cognitive skills declined. In contrast, older individuals in cultures, such as China, that held more positive views on aging did not demonstrate cognitive deficits. It appears that when one agrees with the stereotype, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy or the belief in one’s ability results in actions that make it come true. Being the target of stereotypes can adversely affect individuals’ performance on tasks because they worry they will confirm the cultural stereotypes. This is known as stereotype threat, and it was originally used to explain race and gender differences in academic achievement (Gatz et al., 2016). Stereotype threat research has demonstrated that older adults who internalize the aging stereotypes will exhibit worse memory performance, worse physical performance, and reduced self-efficacy (Levy, 2009).

In terms of physically taking care of themselves, those who believe in negative stereotypes are less likely to engage in preventative health behaviors, less likely to recover from illnesses, and more likely to feel stress and anxiety, which can adversely affect immune functioning and cardiovascular health (Nelson, 2016). Additionally, individuals who attribute their health problems to their age had a higher death rate. Similarly, doctors who believe that illnesses are just a natural consequence of aging are less likely to have older adults participate in clinical trials or receive life-sustaining treatment. In contrast, those older adults who possess positive and optimistic views of aging are less likely to have physical or mental health problems and are more likely to live longer. Removing societal stereotypes about aging and helping older adults reject those notions of aging is another way to promote health and life expectancy among the elderly.

Minority status: Older minority adults accounted for approximately 21% of the U. S. population in 2012 but are expected to reach 39% of the population in 2050 (U. S. Census Bureau, 2012). Unfortunately, racism is a further concern for minority elderly already suffering from ageism. Older adults who are African American, Mexican American, and Asian American experience psychological problems that are often associated with discrimination by the White majority (Youdin, 2016). Ethnic minorities are also more likely to become sick, but less likely to receive medical intervention. Older, minority women can face ageism, racism, and sexism often referred to as triple jeopardy (Hinze, Lin, & Andersson, 2012), which can adversely affect their life in late adulthood.

Poverty rates: According to Quinn and Cahill (2016), the poverty rate for older adults varies based on gender, marital status, race, and age. Women aged 65 or older were 70% more likely to be poor than men, and older women aged 80 and above have higher levels of poverty than those younger. Married couples are less likely to be poor than nonmarried men and women, and poverty is more prevalent among older racial minorities. In 2012 the poverty rates for White older men (5.6%) and White older women (9.6%) were lower than for Black older men (14%), Black older women (21%), Hispanic older men (19%), and Hispanic older women (22%).

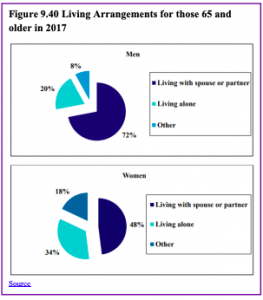

Living Arrangements Do those in late adulthood primarily live alone? No. In 2017, of those 65 years of age and older, approximately 72% of men and 48% of women lived with their spouse or partner (Administration on Aging, 2017). Between 1900 and 1990 the number of older adults living alone increased, most likely due to improvements in health and longevity during this time (see Figure 9.40). Since 1990 the number of older adults living alone has declined, because of older women more likely to be living with their spouse or children (Stepler, 2016c). Women continue to make up the majority of older adults living alone in the U.S., although that number has dropped from those living alone in 1990 (Stepler, 2016a). Older women are more likely to be unmarried, living with children, with other relatives or non-relatives. Older men are more likely to be living alone than they were in 1990, although older men are more likely to reside with their spouses. The rise in divorce among those in late adulthood, along with the drop-in remarriage rate, has resulted in slightly more older men living alone today than in the past (Stepler, 2016c).

Older adults who live alone report feeling more financially strapped than do those living with others (Stepler, 2016d). According to a Pew Research Center Survey, only 33% of those living alone reported they were living comfortably, while nearly 49% of those living with others said they were living comfortably. Similarly, 12% of those living alone, but only 5% of those living with others, reported that they lacked money for basic needs (Stepler, 2016d).

Do those in late adulthood primarily live with family members? No, but according to the Pew Research Center, there has been an increase in the number of families living in multigenerational housing; that is three generations living together than in previous generations (Cohn & Passel, 2018). In 2016, a record 64 million Americans, or 20% of the population, lived in a house with at least two adult generations. However, ethnic differences are noted in the percentage of multigenerational households with Hispanic (27%), Black (26%), and Asian (29%) families living together in greater numbers than White families (16%). Consequently, the majority of older adults wish to live independently for as long as they are able.

Do those in late adulthood move after retirement? No. According to Erber and Szuchman (2015), the majority of those in late adulthood remains in the same location, and often in the same house, where they lived before retiring. Although some younger late adults (65-74 years) may relocate to warmer climates, once they are older (75-84 years) they often return to their home states to be closer to adult children (Stoller & Longino, 2001). Despite the previous trends, however, the recent housing crisis has kept those in late adulthood in their current suburban locations because they are unable to sell their homes (Erber & Szuchman, 2015).

Do those in late adulthood primarily live in institutions? No. Only a small portion (3.2%) of adults older than 65 lived in an institution in 2015 (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). However, as individuals increase in age the percentage of those living in institutions, such as a nursing home, also increases. Specifically: 1% of those 65-74, 3% of those 75-84, and 10% of those 85 years and older lived in an institution in 2015. Due to the increasing number of baby boomers reaching late adulthood, the number of people who will depend on long-term care is expected to rise from 12 million in 2010 to 27 million in 2050 (United States Senate Commission on Long-Term Care, 2013). To meet this higher demand for services, a focus on the least restrictive care alternatives has resulted in a shift toward home and community-based care instead of placement in a nursing home (Gatz et al., 2016).

Erikson: Integrity vs. Despair

How do people cope with old age? According to Erikson, the last psychosocial stage is Integrity vs. Despair. This stage includes, “a retrospective accounting of one’s life to date; how much one embraces life as having been well lived, as opposed to regretting missed opportunities,” (Erikson, 1982, p. 112). Those in late adulthood need to achieve both the acceptance of their life and the inevitability of their death (Barker, 2016). This stage includes finding meaning in one’s life and accepting one’s accomplishments, but also acknowledging what in life has not gone as hoped. It is also feeling a sense of contentment and accepting others’ deficiencies, including those of their parents. This acceptance will lead to integrity, but if elders are unable to achieve this acceptance, they may experience despair. Bitterness and resentment in relationships and life events can lead one to despair at the end of life. According to Erikson (1982), successful completion of this stage leads to wisdom in late life.

Erikson’s theory was the first to propose a lifespan approach to development, and it has encouraged the belief that older adults still have developmental needs. Prior to Erikson’s theory, older adulthood was seen as a time of social and leisure restrictions and a focus primarily on physical needs (Barker, 2016). The current focus on aging well by keeping healthy and active helps to promote integrity. There are many avenues for those in late adulthood to remain vital members of society, and they will be explored next.

Staying Active: Many older adults want to remain active and work toward replacing opportunities lost with new ones. Those who prefer to keep themselves busy demonstrate the Activity Theory, which states that greater satisfaction with one’s life occurs with those who remain active (Lemon, Bengston, & Peterson, 1972). Not surprisingly, more positive views on aging and greater health are noted with those who keep active than those who isolate themselves and disengage from others. Community, faith-based, and volunteer organizations can all provide those in late adulthood with opportunities to remain active and maintain social networks. Erikson’s concept of generativity applies to many older adults, just as it did in midlife.

Generativity in Late Adulthood

Research suggests that generativity is not just a concern for midlife adults, but for many elders, concerns about future generations continue into late adulthood. As previously discussed, some older adults are continuing to work beyond age 65. Additionally, they are volunteering in their community and raising their grandchildren in greater numbers.

Volunteering: Many older adults spend time volunteering. Hooyman and Kiyak (2011) found that religious organizations are the primary settings for encouraging and providing opportunities to volunteer. Hospitals and environmental groups also provide volunteer opportunities for older adults. While volunteering peaks in middle adulthood, it continues to remain high among adults in their 60s, with about 40% engaging in volunteerism (Hooyman & Kiyak, 2011). While the number of older adults volunteering their time does decline with age, the number of hours older adults volunteer does not show much decline until they are in their late 70s (Hendricks & Cutler, 2004). African-American older adults volunteer at higher levels than other ethnic groups (Taylor, Chatters, & Leving, 2004). Taylor and colleagues attribute this to the higher involvement in religious organizations by older African-Americans. Volunteering aids older adults as much as it does the community at large. Older adults who volunteer experience more social contact, which has been linked to higher rates of life satisfaction, and lower rates of depression and anxiety (Pilkington, Windsor, & Crisp, 2012).

Longitudinal research also finds a strong link between health in later adulthood and volunteering (Kahana, Bhatta, Lovegreen, Kahana, & Midlarsky, 2013). Lee and colleagues found that even among the oldest-old, the death rate of those who volunteer is half that of non-volunteers (Lee, Steinman, & Tan, 2011). However, older adults who volunteer may already be healthier, which is why they can volunteer compared to their less healthy age mates. New opportunities exist for older adults to serve as virtual volunteers by dialoguing online with others from around the world and sharing their support, interests, and expertise. These volunteer opportunities range from helping teens with their writing to communicating with ‘neighbors’ in villages of developing countries. Virtual volunteering is available to those who cannot engage in face-to-face interactions, and it opens up a new world of possibilities and ways to connect, maintain identity, and be productive.

Grandparents Raising Grandchildren: According to the 2014 American Community Survey (U.S. Census, 2014a), over 5.5 million children under the age of 18 were living in families headed by a grandparent. This was more than half a million increase from 2010. While most grandparents raising grandchildren are between the ages of 55 and 64, approximately 25% of grandparents raising their grandchildren are 65 and older (Office on Women’s Health, 2010a). For many grandparents, parenting a second time can be harder. Older adults have far less energy, and often the reason why they are now acting as parents to their grandchildren is that traumatic events. A survey by AARP (Goyer, 2010) found that grandparents were raising their grandchildren because the parents had problems with drugs and alcohol, had a mental illness, was incarcerated, had divorced, had a chronic illness, was homeless, had neglected or abused the child, were deployed in the military, or had died. While most grandparents state they gain great joy from raising their grandchildren, they also face greater financial, health, education, and housing challenges that often derail their retirement plans than do grandparents who do not have primary responsibility for raising their grandchildren.

Social Networks in Late Adulthood

A person’s social network consists of the people with whom one is directly involved, such as family, friends, and acquaintances (Fischer, 1982). As individuals age, changes occur in these social networks, and The Convoy Model of Social Relations and Socioemotional Selectivity Theory address these changes (Wrzus, Hanel, Wagner, & Neyer, 2013). Both theories indicate that less close relationships will decrease as one age, while close relationships will persist. However, the two theories differ in explaining why this occurs.

The Convoy Model of Social Relations suggests that the social connections that people accumulate differ in levels of closeness and are held together by exchanges in social support (Antonucci, 2001; Kahn & Antonucci, 1980). According to the Convoy Model, relationships with a spouse and family members, people in the innermost circle of the convoy, should remain stable throughout the lifespan. In contrast, coworkers, neighbors, and acquaintances, people in the periphery of the convoy, should be less stable. These peripheral relationships may end due to changes in jobs, social roles, location, or other life events. These relationships are more vulnerable to changing situations than family relationships. Therefore, the frequency, type, and reciprocity of the social exchanges with peripheral relationships decrease with age.

The Socioemotional Selectivity Theory focuses on changes in motivation for actively seeking social contact with others (Carstensen, 1993; Carstensen, Isaacowitz & Charles, 1999). This theory proposes that with increasing age, our motivational goals change based on how much time one has left to live. Rather than focusing on acquiring information from many diverse social relationships, as noted with adolescents and young adults, older adults focus on the emotional aspects of relationships. To optimize the experience of positive affect, older adults actively restrict their social life to prioritize time spent with emotionally close significant others. In line with this theory, older marriages are found to be characterized by enhanced positive and reduced negative interactions and older partners show more affectionate behavior during conflict discussions than do middle-aged partners (Carstensen, Gottman, & Levenson, 1995). Research showing that older adults have smaller networks compared to young adults, and tend to avoid negative interactions, also supports this theory.

Relationship with Adult Children: Many older adults provide financial assistance and/or housing to adult children. There is more support going from the older parent to the younger adult children than in the other direction (Fingerman & Birditt, 2011). In addition to providing for their own children, many elders are raising their grandchildren. Consistent with socioemotional selectivity theory, older adults seek and are helped by, their adult children providing emotional support (Lang & Schütze, 2002). Lang and Schütze, as part of the Berlin Aging Study (BASE), surveyed adult children (mean age 54) and their aging parents (mean age 84). They found that the older parents of adult children who provided emotional support, such as showing tenderness toward their parent, cheering the parent up when he or she was sad, tended to report greater life satisfaction. In contrast, older adults whose children provided informational support, such as providing advice to the parent, reported less life satisfaction. Lang and Schütze found that older adults wanted their relationship with their children to be more emotionally meaningful. Daughters and adult children who were younger tended to provide such support more than sons and adult children who were older. Lang and Schütze also found that adult children who were more autonomous rather than emotionally dependent on their parents, had more emotionally meaningful relationships with their parents, from both the parents’ and adult children’s point of view.

Friendships: Friendships are not formed in order to enhance status or careers, and may be based purely on a sense of connection or the enjoyment of being together. Most elderly people have at least one close friend. These friends may provide emotional as well as physical support. Being able to talk with friends and rely on others is very important during this stage of life. Bookwala, Marshall, and Manning (2014) found that the availability of a friend played a significant role in protecting health from the impact of widowhood. Specifically, those who became widowed and had a friend as a confidante reported significantly lower somatic depressive symptoms, better self-rated health, and fewer sick days in bed than those who reported not having a friend as a confidante. In contrast, having a family member as a confidante did not provide health protection for those recently widowed.

Loneliness or Solitude: Loneliness is the discrepancy between the social contact a person has and the contacts a person wants (Brehm, Miller, Perlman, & Campbell, 2002). It can result from social or emotional isolation. Women tend to experience loneliness due to social isolation; men from emotional isolation. Loneliness can be accompanied by a lack of self-worth, impatience, desperation, and depression. Being alone does not always result in loneliness. For some, it means solitude. Solitude involves gaining self-awareness, taking care of the self, being comfortable alone, and pursuing one’s interests (Brehm et al., 2002). In contrast, loneliness is perceived as social isolation.

For those in late adulthood, loneliness can be especially detrimental. Novotney (2019) reviewed the research on loneliness and social isolation and found that loneliness was linked to a 40% increase in risk for dementia and a 30% increase in the risk of stroke or coronary heart disease. This was hypothesized to be due to a rise in stress hormones, depression, and anxiety, as well as the individual lacking encouragement from others to engage in healthy behaviors. In contrast, older adults who take part in social clubs and church groups have a lower risk of death. Opportunities to reside in mixed-age housing and continuing to feel like a productive member of society have also been found to decrease feelings of social isolation, and thus loneliness.

Late Adult Lifestyles

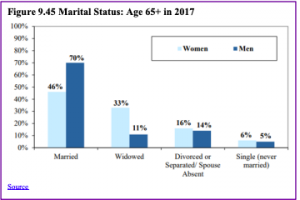

Marriage: As can be seen in Figure 9.45, the most common living arrangement for older adults in 2015 was marriage (AOA, 2017). Although this was more common for older men.

Widowhood: Losing one’s spouse is one of the most difficult transitions in life. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale, commonly known as the Holmes-Rahe Stress Inventory, rates the death of a spouse as the most significant stressor (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). The loss of a spouse after many years of marriage may make an older adult feel adrift in life. They must remake their identity after years of seeing themselves as a husband or wife. Approximately, 1 in 3 women aged 65 and older are widowed, compared with about 1 in 10 men.

Loneliness is the biggest challenge for those who have lost their spouse (Kowalski & Bondmass, 2008). However, several factors can influence how well someone adjusts to this event. Older adults who are more extroverted (McCrae & Costa, 1988) and have higher self-efficacy, (Carr, 2004b) often fare better. Positive support from adult children is also associated with fewer symptoms of depression and better adjustment in the months following widowhood (Ha, 2010).

The context of death is also an important factor in how people may react to the death of a spouse. The stress of caring for an ill spouse can result in a mixed blessing when the ill partner dies (Erber & Szchman, 2015). The death of a spouse who died after a lengthy illness may come as a relief for the surviving spouse, who may have had the pressure of providing care for someone who was increasingly less able to care for themselves. At the same time, this sense of relief may be intermingled with guilt for feeling relief at the passing of their spouse. The emotional issues of grief are complex and will be discussed in more detail in chapter 10.

Widowhood also poses health risks. The widowhood mortality effect refers to the higher risk of death after the death of a spouse (Sullivan & Fenelon, 2014). Subramanian, Elwert, and Christakis (2008) found that widowhood increases the risk of dying from almost all causes.

However, research suggests that the predictability of the spouse’s death plays an important role in the relationship between widowhood and mortality. Elwert and Christakis (2008) found that the rate of mortality for widows and widowers was lower if they had time to prepare for the death of their spouses, such as in the case of a terminal illness like Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s. Another factor that influences the risk of mortality is gender. Men show a higher risk of mortality following the death of their spouse if they have higher health problems (Bennett, Hughes, & Smith, 2005). In addition, widowers have a higher risk of suicide than do widows (Ruckenhauser, Yazdani, & Ravaglia, 2007).

Divorce: As noted in Chapter 8, older adults are divorcing at higher rates than in prior generations. However, adults age 65 and over are still less likely to divorce than middle-aged and young adults (Wu & Schimmele, 2007). Divorce poses a number of challenges for older adults, especially women, who are more likely to experience financial difficulties and are more likely to remain single than are older men (McDonald & Robb, 2004). However, in both America (Lin, 2008) and England (Glaser, Stuchbury, Tomassini, & Askham, 2008) studies have found that the adult children of divorced parents offer more support and care to their mothers than their fathers. While divorced, older men may be better off financially and are more likely to find another partner, they may receive less support from their adult children.

Dating: Due to changing social norms and shifting cohort demographics, it has become more common for single older adults to be involved in dating and romantic relationships (Alterovitz & Mendelsohn, 2011). An analysis of widows and widowers ages 65 and older found that 18 months after the death of a spouse, 37% of men and 15% of women were interested in dating (Carr, 2004a). Unfortunately, opportunities to develop close relationships often diminish in later life as social networks decrease because of retirement, relocation, and the death of friends and loved ones (de Vries, 1996). Consequently, older adults, much like those younger, are increasing their social networks using technologies, including e-mail, chat rooms, and online dating sites (Fox, 2004; Wright & Query, 2004; Papernow, 2018).

Interestingly, older men and women parallel online dating information as those younger. Alterovitz and Mendelsohn (2011) analyzed 600 internet personal ads from different age groups, and across the life span, men sought physical attractiveness and offered status-related information more than women. With advanced age, men desired women increasingly younger than themselves, whereas women desired older men until ages 75 and over when they sought men younger than themselves. Research has previously shown that older women in romantic relationships are not interested in becoming a caregiver or becoming widowed for a second time (Carr, 2004a). Additionally, older men are more eager to partner than are older women (Davidson, 2001; Erber & Szuchman, 2015). Concerns expressed by older women included not wanting to lose their autonomy, care for a potentially ill partner, or merge their finances with someone (Watson & Stelle, 2011).

Older dating adults also need to know about threats to sexual health, including being at risk for sexually transmitted diseases, including chlamydia, genital herpes, and HIV. Nearly 25% of people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States are 50 or older (Office on Women’s Health, 2010b). Githens and Abramsohn (2010) found that only 25% of adults 50 and over who were single or had a new sexual partner used a condom the last time they had sex. Robin (2010) stated that 40% of those 50 and over have never been tested for HIV. These results indicated that educating all individuals, not just adolescents, on healthy sexual behavior is important.

Remarriage and Cohabitation: Older adults who remarry often find that their remarriages are more stable than those of younger adults. Kemp and Kemp (2002) suggest that greater emotional maturity may lead to more realistic expectations regarding marital relationships, leading to greater stability in remarriages in later life. Older adults are also more likely to be seeking companionship in their romantic relationships. Carr (2004a) found that older adults who have considerable emotional support from their friends were less likely to seek romantic relationships. In addition, older adults who have divorced often desire the companionship of intimate relationships without marriage. As a result, cohabitation is increasing among older adults, and like remarriage, cohabitation in later adulthood is often associated with more positive consequences than it is in younger age groups (King & Scott, 2005). No longer being interested in raising children, and perhaps wishing to protect family wealth, older adults may see cohabitation as a good alternative to marriage. In 2014, 2% of adults age 65 and up were cohabitating (Stepler, 2016b).

Living Apart Together: In addition to cohabiting there has been an increase in living apart together (LAT), which is “a monogamous intimate partnership between unmarried individuals who live in separate homes but identify themselves as a committed couple” (Benson & Coleman, 2016, p. 797). This trend has been found in several nations and is motivated by:

- A strong desire to be independent in day-to-day decisions

- Maintaining their own home

- Keeping boundaries around established relationships

- Maintaining financial stability

Besides the desire to be autonomous, there is also a need for companionship, sexual intimacy, and emotional support. According to Bensen and Coleman, there are differences in LAT among older and younger adults. Those who are younger often enter into LAT out of circumstances, such as the job market, and they frequently view this arrangement as a transitional stage. In contrast, 80% of older adults reported that they did not wish to cohabitate or marry. For some, it was a conscious choice to live more independently. For instance, older women desired the LAT lifestyle as a way of avoiding the traditional gender roles that are often inherent in relationships where the couple lives together. However, some older adults become LATs because they fear social disapproval from others if they were to live together.

Gay and Lesbian Elders

Approximately 3 million older adults in the United States identify as lesbian or gay (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). By 2025 that number is expected to rise to more than 7 million (National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2006). Despite the increase in numbers, older lesbian and gay adults are one of the least researched demographic groups, and the research there is portrayed a population faced with discrimination. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011), compared to heterosexuals, lesbian and gay adults experience both physical and mental health differences. More than 40% of lesbian and gay adults ages 50 and over suffer from at least one chronic illness or disability and compared to heterosexuals they are more likely to smoke and binge drink (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). Additionally, gay older adults have an increased risk of prostate cancer (Blank, 2005) and infection from HIV and other sexually transmitted illnesses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). When compared to heterosexuals, lesbian and gay elders have less support from others as they are twice as likely to live alone and four times less likely to have adult children (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014).

Lesbian and gay older adults who belong to ethnic and cultural minorities, conservative religions, and rural communities may face additional stressors. Ageism, heterocentrism, sexism, and racism can combine cumulatively and impact the older adult beyond the negative impact of each individual form of discrimination (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). David and Knight (2008) found that older gay black men reported higher rates of racism than younger gay black men and higher levels of perceived ageism than older gay white men.

LGBT Elder Care: Approximately 7 million LGBT people over age 50 will reside in the United States by 2030, and 4.7 million of them will need elder care. Decisions regarding elder care are often left for families, and because many LGBT people are estranged from their families, they are left in a vulnerable position when seeking living arrangements (Alleccia & Bailey, 2019). A history of discriminatory policies, such as housing restricted to married individuals involving one man and one woman, and stigma associated with LGBT people make them especially vulnerable to negative housing experiences when looking for eldercare.

Although lesbian and gay older adults face many challenges, more than 80% indicate that they engage in some form of wellness or spiritual activity (Fredrickson-Goldsen et al., 2011). They also gather social support from friends and “family members by choice” rather than legal or biological relatives (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). This broader social network provides extra support to gay and lesbian elders.

An important consideration when reviewing the development of gay and lesbian older adults is the cohort in which they grew up (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). The oldest lesbian and gay adults came of age in the 1950s when there were no laws to protect them from victimization. The baby boomers, who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s, began to see states repeal laws that criminalized homosexual behavior. Future lesbian and gay elders will have different experiences due to the legal right for same-sex marriage and greater societal acceptance. Consequently, just like all those in late adulthood, understanding that gay and lesbian elders are a heterogeneous population is important when understanding their overall development.

Current research indicates that at least 1 in 10, or approximately 4.3 million, older Americans are affected by at least one form of elder abuse per year (Roberto, 2016). Those between 60 and 69 years of age are more susceptible than those older. This may be because younger older adults more often live with adult children or a spouse, two groups with the most likely abusers.

Cognitive impairment, including confusion and communication deficits, is the greatest risk factor for elder abuse, while a decline in overall health resulting in a greater dependency on others is another. Having a disability also places an elder at a higher risk for abuse (Youdin, 2016). Definitions of elder abuse typically recognize five types of abuse as shown in Table 9.8

The consequences of elder abuse are significant and include injuries, new or exacerbated health conditions, hospitalizations, premature institutionalization, and early death (Roberto, 2016). Psychological and emotional abuse is considered the most common form, even though it is underreported and may go unrecognized by the elder. Continual emotional mistreatment is very damaging as it becomes internalized and results in late-life emotional problems and impairment. Financial abuse and exploitation is increasing and costs seniors nearly 3 billion dollars per year (Lichtenberg, 2016). Financial abuse is the second most common form after emotional abuse and affects approximately 5% of elders. Abuse and neglect occurring in a nursing home is estimated to be 25%-30% (Youdin, 2016). Abuse of nursing home residents is more often found in facilities that are run down and understaffed

| Type | Description |

| Physical Abuse | Physical force resulting in injury, pain, or impairment |

| Sexual Abuse | Nonconsensual sexual contact |

| Psychological and Emotional Abuse | Infliction of distress through verbal or nonverbal acts such as yelling, threatening, or isolating |

| Financial Abuse and Exploitation | Improper use of an elder’s finances, property, or assets |

| Neglect and Abandonment | Intentional or unintentional refusal or failure to fulfill caregiving duties to an elder |

Older women are more likely to be victims than men, and one reason is due to women living longer. Additionally, a family history of violence makes older women more vulnerable, especially for physical and sexual abuse (Acierno et al., 2010). However, Kosberg (2014) found that men were less likely to report abuse. Recent research indicated no differences among ethnic groups in abuse prevalence, however, cultural norms regarding what constitutes abuse differ based on ethnicity. For example, Dakin and Pearlmutter found that working-class White women did not consider verbal abuse as elder abuse, and higher socioeconomic status African American and White women did not consider financial abuse as a form of elder abuse (as cited in Roberto, 2016, p. 304).

Perpetrators of elder abuse are typically family members and include spouses/partners and older children (Roberto, 2016). Children who are abusive tend to be dependent on their parents for financial, housing, and emotional support. Substance use, mental illness, and chronic unemployment increase dependency on parents, which can then increase the possibility of elder abuse. Prosecuting a family member who has financially abused a parent is very difficult. The victim may be reluctant to press charges and the court dockets are often very full resulting in long waits before a case is heard. According to Tanne, family members abandoning older family members with severe disabilities in emergency rooms is a growing problem as an estimated 100,000 are dumped each year (as cited in Berk, 2007). Paid caregivers and professionals trusted to make decisions on behalf of an elder, such as guardians and lawyers, also perpetuate abuse. When elders feel they have social support and are engaged with others, they are less likely to suffer abuse.

Substance Abuse and the Elderly

Alcohol and drug problems, particularly prescription drug abuse, have become a serious health concern among older adults. Although people 65 years of age and older make up only 13% of the population, they account for almost 30% of all medications prescribed in the United States. According to the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (NCADD) (2015), the following statistics illustrate the significance of substance abuse for those in late adulthood:

- There are 2.5 million older adults with an alcohol or drug problem.

- Six to eleven percent of elderly hospital admissions, 14 percent of elderly emergency room admissions, and 20 percent of elderly psychiatric hospital admissions are a result of alcohol or drug problems.

- Widowers over the age of 75 have the highest rate of alcoholism in the U.S.

- Nearly 50 percent of nursing home residents have alcohol-related problems.

- Older adults are hospitalized as often for alcoholic related problems as for heart attacks.

- Nearly 17 million prescriptions for tranquilizers are prescribed for older adults each year. Benzodiazepines, a type of tranquilizing drug, are the most commonly misused and abused prescription medications.

Risk factors for psychoactive substance abuse in older adults include social isolation, which can lead to depression (Youdin, 2016). This can be caused by the death of a spouse/partner, family members and/or friends, retirement, moving, and reduced activity levels. Additionally, medical conditions, chronic pain, anxiety, and stress can all lead to the abuse of substances.

Diagnosis Difficulties: Using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorder-5th Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), diagnosing older adults with a substance use disorder can be difficult (Youdin, 2016). For example, compared to adolescents and younger adults, older adults are not looking to get high, but rather become dependent by accident.

Additionally, stereotypes of older adults, which include memory deficits, confusion, depression, agitation, motor problems, and hostility, can result in a diagnosis of cognitive impairment instead of a substance use disorder. Further, a diagnosis of a substance use disorder involves impairment in work, school, or home obligations, and because older adults are not typically working, in school or caring for children, these impairments would not be exhibited. Stigma and shame about use, as well as the belief that one’s use is a private matter, may keep older adults from seeking assistance. Lastly, physicians may be biased against asking those in late adulthood if they have a problem with drugs or alcohol (NCADD, 2015).

Abused Substances: Drugs of choice for older adults include alcohol, benzodiazepines, opioid prescription medications, and marijuana. The abuse of prescription medications is expected to increase significantly. Siriwardena, Qureshi, Gibson, Collier, and Lathamn (2006) found that family physicians prescribe benzodiazepines and opioids to older adults to deal with psychosocial and pain problems rather than prescribe alternatives to medication such as therapy. Those in late adulthood are also more sensitive to the effects of alcohol than those younger because of an age-related decrease in the ratio between lean body mass and fat (Erber & Szuchman, 2015).

Additionally, “liver enzymes that metabolize alcohol become less efficient with age and central nervous system sensitivity to drugs increase with age” (p.134). Those in late adulthood are also more likely to be taking other medications, and this can result in unpredictable interactions with psychoactive substances (Youdin, 2016).

Cannabis Use: Blazer and Wu (2009) found that adults aged 50-64 were more likely to use cannabis than older adults. These “baby boomers” with the highest cannabis use included men, those unmarried/unpartnered, and those with depression. In contrast to the negative effects of cannabis, which include panic reactions, anxiety, perceptual distortions and exacerbation of mood and psychotic disorders, cannabis can provide benefits to an older adults with medical conditions (Youdin, 2016). For example, cannabis can be used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, chronic pain, and fatigue and nausea from the effects of chemotherapy (Williamson & Evans, 2000).

Future Substance Abuse Concerns: There will be an increase in the number of seniors abusing substances in the future because the baby boomer generation has a history of having been exposed to, and having experienced, psychoactive substance use over their adult life. This is a significant difference between the current and previous generations of older adults (National Institutes of Health, 2014c). Efforts will be needed to adequately address these future substance abuse issues for the elderly due to both the health risks for them and the expected burden on the health care system.

Successful Aging

Although definitions of successful aging are value-laden, Rowe and Kahn (1997) defined three criteria of successful aging that are useful for research and behavioral interventions.

They include:

- Relative avoidance of disease, disability, and risk factors, like high blood pressure, smoking, or obesity

- Maintenance of high physical and cognitive functioning

- Active engagement in social and productive activities

For example, research has demonstrated that age-related declines in cognitive functioning across the adult life span may be slowed through physical exercise and lifestyle interventions (Kramer & Erickson, 2007).

Another way that older adults can respond to the challenges of aging is through compensation. Specifically, selective optimization with compensation is used when the elder makes adjustments, as needed, in order to continue living as independently and actively as possible (Baltes & Dickson, 2001). When older adults lose functioning, referred to as loss-based selection, they may first use new resources/technologies or continually practice tasks to maintain their skills. However, when tasks become too difficult, they may compensate by choosing other ways to achieve their goals. For example, a person who can no longer drive needs to find alternative transportation, or a person who is compensating for having less energy learns how to reorganize the daily routine to avoid over-exertion.

References

Acierno, R., Hernandez, M. A., Amstadter, A. B., Resnick, H. S., Steve, K., Muzzy, W., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 292-297.

Administration on Aging. (2017). 2017 Profile of older Americans. Retrieved from: https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2017OlderAmericansProfile.pdf

Alleccia, J., & Bailey, M. (2019, June 12). A concern for LGBT boomers. The Chicago Tribune, pp. 1-2.

Alterovitz, S. S., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2011). Partner preferences across the lifespan: Online dating by older adults. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1, 89-95.

Alzheimer’s Association. (2016). Know the 10 signs. Early detection matters. Retrieved from: http://www.alz.org/national/documents/tenwarnsigns.pdf

American Federation of Aging Research. (2011). Theories of aging. Retrieved from http://www.afar.org/docs/migrated/111121_INFOAGING_GUIDE_THEORIES_OF_AGINGFR.pdf

American Heart Association. (2014). Overweight in children. Retrieved from http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/HealthyKids/ChildhoodObesity/Overweight-in- Children_UCM_304054_Article.jsp#.V5EIlPkrLIU

American Lung Association. (2018). Taking her breath away: The rise of COPD in women. Retrieved from https://www.lung.org/assets/documents/research/rise-of-copd-in-women-full.pdf

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychological Association. (2016). Older adults’ health and age-related changes. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/aging/resources/guides/older.aspx

Andrés, P., Van der Linden, M., & Parmentier, F. B. R. (2004). Directed forgetting in working memory: Age-related differences. Memory, 12, 248-256.

Antonucci, T. C. (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support and sense of control. In J.E. Birren & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (5th ed., pp. 427–453). New York: Academic Press.

Arias, E., & Xu, J. (2019). United States life tables, 2017. National Vital Statistics Reports, 68(7), 1-66.

Arthritis Foundation. (2017). What is arthritis? Retrieved from http://www.arthritis.org/about-arthritis/understanding- arthritis/what-is-arthritis.php

Ash, A. S., Kroll-Desroisers, A. R., Hoaglin, D. C., Christensen, K., Fang, H., & Perls, T. T. (2015). Are members of long-lived families healthier than their equally long-lived peers? Evidence from the long life family study. Journal of Gerontology: Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. Advance online publication. doi:10.1093/gerona/glv015

Atchley, R. C. (1994). Social forces and aging (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Balducci, L., & Extermann, M. (2000). Management of cancer if the older person: A practical approach. The Oncologist. Retrieved from http://theoncologist.alphamedpress.org/content/5/3/224.full

Baltes, B. B., & Dickson, M. W. (2001). Using life-span models in industrial/organizational psychology: The theory of selective optimization with compensation (soc). Applied Developmental Science, 5, 51-62.

Baltes, P. B. (1993). The aging mind: Potential and limits. The Gerontologist, 33, 580-594.

Baltes, P.B. & Kunzmann, U. (2004). The two faces of wisdom: Wisdom as a general theory of knowledge and judgment about excellence in mind and virtue vs. wisdom as everyday realization in people and products. Human Development, 47(5), 290-299.

Baltes, P. B. & Lindenberger, U. (1997). Emergence of powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: A new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology and Aging, 12, 12–21.

Baltes, P. B., & Staudinger, U. M. (2000). Wisdom: A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. American Psychologist, 55 (1), 122-136.

Barker, (2016). Psychology for nursing and healthcare professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Barnes, S. F. (2011a). Fourth age-the final years of adulthood. San Diego State University Interwork Institute. Retrieved from http://calbooming.sdsu.edu/documents/TheFourthAge.pdf

Barnes, S. F. (2011b). Third age-the golden years of adulthood. San Diego State University Interwork Institute. Retrieved from http://calbooming.sdsu.edu/documents/TheThirdAge.pdf

Bartlett, Z. (2014). The Hayflick limit. Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/8237

Bennett, K. M., Hughes, G. M., & Smith, P. T. (2005). Psychological response to later life widowhood: Coping and the effects of gender. Omega, 51, 33-52.

Benson, J.J., & Coleman, M. (2016). Older adults developing a preference for living apart together. Journal of Marriage and Family, 18, 797-812.

Berger, N. A., Savvides, P., Koroukian, S. M., Kahana, E. F., Deimling, G. T., Rose, J. H., Bowman, K. F., & Miller, R. H. (2006). Cancer in the elderly. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 117, 147-156.

Berk, L. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Blanchard-Fields, F. (2007). Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult development perspective. Current Directions in Psychoogical Science, 16, 26–31

Blank, T. O. (2005). Gay men and prostate cancer: Invisible diversity. American Society of Clinical Oncology, 23, 2593–2596. doi:10.1200/ JCO.2005.00.968

Blazer, D. G., & Wu, L. (2009). The epidemiology of substance use and disorders among middle aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 237-245.

Bookwala, J., Marshall, K. I., & Manning, S. W. (2014). Who needs a friend? Marital status transitions and physical health outcomes in later life. Health Psychology, 33(6), 505-515.

Borysławski, K., & Chmielewski, P. (2012). A prescription for healthy aging. In: A Kobylarek (Ed.), Aging: Psychological, biological and social dimensions (pp. 33-40). Wrocław: Agencja Wydawnicza.

Botwinick, J. (1984). Aging and behavior (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

Bowden, J. L., & McNulty, P. A. (2013). Age-related changes in cutaneous sensation in the healthy human hand. Age (Dordrecht, Netherlannds), 35(4), 1077-1089.

Boyd, K. (2014). What are cataracts? American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved from http://www.aao.org/eye- health/diseases/what-are-cataracts

Boyd, K. (2016). What is macular degeneration? American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved from http://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/amd-macular-degeneration

Brehm, S. S., Miller, R., Perlman, D., & Campbell, S. (2002). Intimate relationships (3rd ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Buman, M. P. (2013). Does exercise help sleep in the elderly? Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/ask-the-expert/does-exercise-help-sleep-the-elderly

Cabeza, R., Anderson, N. D., Locantore, J. K., & McIntosh, A. R. (2002). Aging gracefully: Compensatory brain activity in high- performing older adults. NeuroImage, 17, 1394-1402.

Carlson, N. R. (2011). Foundations of behavioral neuroscience (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Carr, D. (2004a). The desire to date and remarry among older widows and widowers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1051– 1068.

Carr, D. (2004b). Gender, preloss marital dependence, and older adults’ adjustment to widowhood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 220-235.

Carstensen, L. L. (1993). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In J. E. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 209–254). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Carstenson, L. L., Fung, H. H., & Charles, S. T. (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 103-123.

Carstensen, L. L., Gottman, J. M., & Levensen, R. W. (1995). Emotional behavior in long-term marriage. Psychology and Aging, 10, 140–149.

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165–181.

Caruso, C., Accardi, G., Virruso, C., & Candore, G. (2013). Sex, gender and immunosenescence: A key to understand the different lifespan between men and women? Immunity & Ageing, 10, 20.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Persons age 50 and over: Centers for disease control and prevention. Atlanta, GA: Author.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Percent of U. S. adults 55 and over with chronic conditions. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Rationale for regular reporting on health disparities and inequalities—United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60, 3–10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). State-Specific Healthy Life Expectancy at Age 65 Years — United States, 2007–2009. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6228a1.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016b). Older Persons’ Health. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm

Central Intelligence Agency. (2019). The world factbook. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world- factbook/fields/355rank.html

Charness, N. (1981). Search in chess: Age and skill differences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 7, 467.

Cheng, S. (2016). Cognitive reserve and the prevention of dementia: The role of physical and cognitive activities. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(9), 85.

Chmielewski, P., Boryslawski, K., & Strzelec, B. (2016). Contemporary views on human aging and longevity. Anthropological Review, 79(2), 115-142.

Cohen, D., & Eisdorfer, C. (2011). Integrated textbook of geriatric mental health. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Cohen, R. M. (2011). Chronic disease: The invisible illness. AARP. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-06-2011/chronic-disease-invisible-illness.html

Cohn, D., & Passel, J. (2018). A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/05/a-record-64-million-americans-live-in-multigenerational- households/

Craik, F. I., & Bialystok, E. (2006). Cognition through the lifespan: mechanisms of change. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10, 131–138.

Dahlgren, D. J. (1998). Impact of knowledge and age on tip-of-the-tongue rates. Experimental Aging Research, 24, 139-153. Dailey, S., & Cravedi, K. (2006). Osteoporosis information easily accessible NIH senior health. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/newsroom/2006/01/osteoporosis-information-easily-accessible-nihseniorhealth

David, S., & Knight, B. G. (2008). Stress and coping among gay men: Age and ethnic differences. Psychology and Aging, 23, 62– 69. doi:10.1037/ 0882-7974.23.1.62

Davidson, K. (2001). Late life widowhood, selfishness and new partnership choices: A gendered perspective. Ageing and Society, 21, 297–317.

Department of Defense. (2015). Defense advisory committee on women in the services. Retrieved from http://dacowits.defense.gov/Portals/48/Documents/Reports/2015/Annual%20Report/2015%20DACOWITS%20Annual%20Report_Final.pdf

de Vries, B. (1996). The understanding of friendship: An adult life course perspective. In C. Magai & S. H. McFadden (Eds.), Handbook of emotion, adult development, and aging (pp. 249–268). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

DiGiacomo, R. (2015). Road scholar, once elderhostel, targets boomers. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/nextavenue/2015/10/05/road-scholar-once-elderhostel-targets-boomers/#fcb4f5b64449

Dixon R. A., & Cohen, A. L. (2003). Cognitive development in adulthood. In R. M. Lerner, M. A. Easterbrokks & J. Misty (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (pp. 443-461). Hoboken NJ: John Wiley.

Dixon, R. A., Rust, T. B., Feltmate, S. E., & See, S. K. (2007). Memory and aging: Selected research directions and application issues. Canadian Psychology, 48, 67-76.

Dollemore, D. (2006, August 29). Publications. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved from http://www.nia.nih.gov/HealthInformation/Publications?AgingUndertheMicroscope/

Economic Policy Institute. (2013). Financial security of elderly Americans at risk. Retrieved from http://www.epi.org/publication/economic-security-elderly-americans-risk

Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. (2008). The effect of widowhood on mortality by the causes of death of both spouses. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 2092-2098.

Erber, J. T., & Szuchman, L. T. (2015). Great myths of aging. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York, NY: Norton & Company.

Farrell, M. J. (2012). Age-related changes in the structure and function of brain regions involved in pain processing. Pain Medication, 2, S37-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01287.x.

Federal Bureau of Investigation.üü (2014). Crime in the United States. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the- u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.s.-2014/tables/expanded- homicide- data/expanded_homicide_data_table_1_murder_victims_by_race_ethnicity_and_sex_2014.xls

Fingerman, K. L., & Birditt, K. S. (2011). Relationships between adults and their aging parents. In K. W. Schaie & S. I Willis (Eds.). Handbook of the psychology of aging (7th ed.) (pp 219-232). SanDiego: Elsevier Academic Press.

Fischer, C. S. (1982). To dwell among friends: Personal networks in town and city. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Fjell, A. M., & Walhovd, K. B. (2010). Structural brain changes in aging: Courses, causes, and cognitive consequences. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 21, 187-222.

Fox, S. (2004). Older Americans and the Internet. PEW Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/report_display.asp?r_117

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H. J., Emlet, C. A., Muraco, A., Erosheva, E. A., Hoy-Ellis, C. P.,… Petry, H. (2011). The aging and health report: disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Seattle, WA: Institute for Multigenerational Health.

Garrett, B. (2015). Brain and behavior (4th ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gatz, M., Smyer, M. A., & DiGilio, D. A. (2016). Psychology’s contribution to the well-being of older Americans. American Psychologist, 71(4), 257-267.

Gems, D. (2014). Evolution of sexually dimorphic longevity in humans. Aging, 6, 84-91.

George, L.K. (2009). Still happy after all these years: research frontiers on subjective well-being in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 65B (3), 331–339. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbq006

Githens, K., & Abramsohn, E. (2010). Still got it at seventy: Sexuality, aging, and HIV. Achieve, 1, 3-5.

Glaser, K., Stuchbury, R., Tomassini, C., & Askham, J. (2008). The long-term consequences of partnership dissolution for support in later life in the Unites Kingdom. Ageing & Society, 28(3), 329-351.

Gosney, T. A. (2011). Sexuality in older age: Essential considerations for healthcare professionals. Age Ageing, 40(5), 538-543. Göthe, K., Oberauer, K., & Kliegl, R. (2007). Age differences in dual-task performance after practice. Psychology and Aging, 22, 596-606.

Goyer, A. (2010). More grandparents raising grandkids: New census data shows and increase in children being raised by extended family. AARP. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/relationships/grandparenting/info-12- 2010/more_grandparents_raising_grandchildren.html

Graham, J. (2019, July 10). Why many seniors rate their health positively. The Chicago Tribune, p. 2.

Greenfield, E. A., Vaillant, G. E., & Marks, N. F. (2009). Do formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions have independent linkages with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 196-212.

Guinness World Records. (2016). Oldest person (ever). Retrieved from http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/search?term=oldest+person+%28ever%29

Ha, J. H. (2010). The effects of positive and negative support from children on widowed older adults’ psychological adjustment: A longitudinal analysis. Gerontologist, 50, 471-481.

Harkins, S. W., Price, D. D. & Martinelli, M. (1986). Effects of age on pain perception. Journal of Gerontology, 41, 58-63.

Harvard School of Public Health. (2016). Antioxidants: Beyond the hype. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/antioxidants

Hasher, L. & Zacks, R. T. (1988). Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In G.H. Bower (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, (Vol. 22, pp. 193–225). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

He, W., Goodkind, D., & Kowal, P. (2016). An aging world: 2015. International Population Reports. U.S. Census Bureau.

He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (2005.). U. S. Census Bureau, Current Popluation Reports, P23-209, 65+ in the United States: 2005 (United States, U. S. Census Bureau). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p23- 190/p23-190.html

Hendricks, J., & Cutler, S. J. (2004). Volunteerism and socioemotional selectivity in later life. Journal of Gerontology, 59B, S251-S257.

Henry, J. D., MacLeod, M. S., Phillips, L. H., & Crawford, J. R. (2004). A meta-analytic review of prospective memory and aging. Psychology and Aging, 19, 27–39.

Heron, M. (2018). Deaths: Leading causes 2016. National Vital Statistics Reports, 67(6), 1-77.

Hillman, J., & Hinrichsen, G. A. (2014). Promoting and affirming competent practice with older lesbian and gay adults. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(4), 169-277.

Hinze, S. W., Lin, J., & Andersson, T. E. (2012). Can we capture the intersections? Older black women, education, and health. Women’s Health Issues, 22, e91-e98.

Hirokawa K., Utsuyama M., Hayashi, Y., Kitagawa, M., Makinodan, T., & Fulop, T. (2013). Slower immune system aging in women versus men in the Japanese population. Immunity & Ageing, 10(1), 19.

Holland, K. (2014). Why America’s campuses are going gray? Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/2014/08/28/why-americas- campuses-are-going-gray.html

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of psychosomatic research, 11, 213.

Holth, J., Fritschi, S., Wang, C., Pedersen, N., Cirrito, J., Mahan, T.,…Holtzman, D. 2019). The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Science, 363(6429), 880-884.

Hooyman, N. R., & Kiyak, H. A. (2011). Social gerontology: A multidisciplinary perspective (9th Ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson James, J. B., Matz-Costa, C., & Smyer, M. A. (2016). Retirement security: It’s not just about the money. American Psychologist, 71(4), 334-344.

Jarrett, C. (2015). Great myths of the brain. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Jefferies, L. N., Roggeveen, A. B., Ennis, J. T., Bennett, P. J., Sekuler, A. B., & Dilollo, V. (2015). On the time course of attentional focusing in older adults. Psychological Research, 79, 28-41.

Jensen, M. P., Moore, M. R., Bockow, T. B., Ehde, D. M., & Engel, J. M. (2011). Psychosocial factors and adjustment to persistent pain in persons with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 92, 146–160. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010 .09.021

Jin, K. (2010). Modern biological theories of aging. Aging and Disease, 1, 72-74.

Kahana, E., Bhatta, T., Lovegreen, L. D., Kahana, B., & Midlarsky, E. (2013). Altruism, helping, and volunteering: Pathways to well-being in late life. Journal of Aging and Health, 25(1), 159-187.

Kahn, R. L., & Antonucci, T. C. (1980). Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support. In P. B. Baltes & O. G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (pp. 253–286). New York: Academic Press.

Kane, M. (2008). How are sexual behaviors of older women and older men perceived by human service students? Journal of Social Work Education, 27(7), 723-743.

Karraker, A., DeLamater, J., & Schwartz, C. R. (2011). Sexual frequency decline from midlife to later life. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B, 502-512.

Kaskie, B., Imhof, S., Cavanaugh, J., & Culp, K. (2008). Civic engagement as a retirement role for aging Americans. The Gerontologist, 48, 368-377.

Kemp, E. A., & Kemp, J. E. (2002). Older couples: New romances: Finding and keeping love in later life. Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts.

King, V., & Scott, M. E. (2005). A comparison of cohabitating relationships among older and younger adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 271-285.

Kolb, B., & Whishaw, I. Q. (2011). An introduction to brain and behavior (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

Kosberg, J. I. (2014). Reconsidering assumptions regarding men an elder abuse perpetrators and as elder abuse victims. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 26, 207-222.

Kowalski, S. D., & Bondmass, M. D. (2008). Physiological and psychological symptoms of grief in widows. Research in Nursing and Health, 31(1), 23-30.

Kramer, A. F. & Erickson, K. I. (2007). Capitalizing on cortical plasticity: The influence of physical activity on cognition and brain function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 342–348.

Lang, F. R., & Schütze, Y. (2002). Adult children’s supportive behaviors and older adults’ subjective well-being: A developmental perspective on intergenerational relationships. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 661-680.

Laslett, P. (1989). A fresh map of life: The emergence of the third age. London, UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Lee, S.B., Oh, J.G., Park, J.H., Choi, S.P., & Wee, J.H. (2018). Differences in youngest-old, middle-old, and oldest-old patients who visit the emergency department. Clinical and Experimental Emergency Medicine, 5(4), 249-255.

Lee, S. J., Steinman, M., & Tan, E. J. (2011). Volunteering, driving status, and mortality in U.S. retirees. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 59 (2), 274-280. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03265x

Lemon, F. R., Bengston, V. L., & Peterson, J. A. (1972). An exploration of activity theory of aging: Activity types and life satisfaction among in-movers to a retirement community. Journal of Geronotology, 27, 511-523.

Levant, S., Chari, K., & DeFrances, C. J. (2015). Hospitalizations for people aged 85 and older in the United States 2000-2010. Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db182.pdf

Levy, B. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 332-336.

Lichtenberg, P. A. (2016). Financial exploitation, financial capacity, and Alzheimer’s disease. American Psychologist, 71(4), 312-320.

Lin, I. F. (2008). Consequences of parental divorce for adult children’s support of their frail parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(1), 113-128.

Livingston, G. (2019). Americans 60 and older are spending more time in front of their screens than a decade ago. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/18/americans-60-and-older-are-spending-more-time-in-front-of- their-screens-than-a-decade-ago/

Luo, L., & Craik, F. I. M. (2008). Aging and memory: A cognitive approach. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 53, 346-353. Martin, L. J. (2014). Age changes in the senses. MedlinePlus. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004013.htm

Martin, P., Poon, L.W., & Hagberg, B. (2011). Behavioral factors of longevity. Journal of Aging Research, 2011/2012, 1–207.

Mayer, J. (2016). MyPlate for older adults. Nutrition Resource Center on Nutrition and Aging and the U. S. Department of Agriculture Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging and Tufts University. Retrieved from http://nutritionandaging.org/my-plate-for-older-adults/

McCormak A., Edmondson-Jones M., Somerset S., & Hall D. (2016) A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hearing Research, 337, 70-79.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1988). Physiological resilience among widowed men and women: A 10 year follow-up study of a national sample. Journal of Social Issues, 44(3), 129-142.

McDonald, L., & Robb, A. L. (2004). The economic legacy of divorce and separation for women in old age. Canadian Journal on Aging, 23, 83-97.

McEntarfer, E. (2018). Older people working longer, earning more. Retrieved from http://thepinetree.net/new/?p=58015

Meegan, S. P., & Berg, C. A. (2002). Contexts, functions, forms, and processes of collaborative everyday problem solving in older adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26(1), 6-15. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000283

Molton, I. R., & Terrill, A. L. (2014). Overview of persistent pain in older adults. American Psychologist, 69(2), 197-207. Natanson, H. (2019, July 14). To reduce risk of Alzheimer’s play chess and ditch red meat. The Chicago Tribune, p. 1.

National Council on Aging. (2019). Healthy aging facts. Retrieved from https://www.ncoa.org/news/resources-for-reporters/get- the-facts/healthy-aging-facts/

National Council on Alcoholism and Drug. (2015). Alcohol, drug dependence and seniors. Retrieved from https://www.ncadd.org/about-addiction/seniors/alcohol-drug-dependence-and-seniors

National Eye Institute. (2016a). Cataract. Retrieved from https://nei.nih.gov/health/cataract/

National Eye Institute. (2016b). Glaucoma. Retrieved from https://nei.nih.gov/glaucoma/

National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. (2006). Make room for all: Diversity, cultural competency and discrimination in an aging America. Washington, DC: The Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

National Institutes of Health. (2011). What is alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency? Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/aat

National Institutes of Health. (2013). Hypothyroidism. Retrieved from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health- topics/endocrine/hypothyroidism/Pages/fact-sheet.aspx

National Institutes of Health. (2014a). Aging changes in hormone production. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004000.htm

National Institutes of Health. (2014b). Cataracts. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/cataract.html

National Institutes of Health. (2014c). Prescription and illicit drug abuse. NIH Senior Health: Built with you in mind. Retrieved from http://nihseniorhealth.gov/drugabuse/illicitdrugabuse/01.html

National Institutes of Health. (2015a). Macular degeneration. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/maculardegeneration.html

National Institutes of Health. (2015b). Pain: You can get help. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/pain

National Institutes of Health. (2016). Quick statistics about hearing. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing

National Institutes of Health: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2014). Arthritis and rheumatic diseases. Retrieved from https://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Arthritis/arthritis_rheumatic.asp

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health. (2013). What is COPD? Retrieved from http://nihseniorhealth.gov/copd/whatiscopd/01.html

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health. (2015). What is osteoporosis? http://nihseniorhealth.gov/osteoporosis/whatisosteoporosis/01.html

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health (2016a). Problems with smell. Retrieved from https://nihseniorhealth.gov/problemswithsmell/aboutproblemswithsmell/01.html

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health (2016b). Problems with taste. Retrieved from https://nihseniorhealth.gov/problemswithtaste/aboutproblemswithtaste/01.html

National Institute on Aging. (2011a). Biology of aging: Research today for a healthier tomorrow. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/biology-aging/preface

National Institute on Aging. (2011b). Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging Home Page. (2011). Retrieved from http://www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/blsa/blsa.htm

National Institute on Aging. (2012). Heart Health. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/heart-health

National Institute on Aging. (2013). Sexuality later in life. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/sexuality- later-life

National Institute on Aging. (2015a). The Basics of Lewy Body Dementia. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/lewy-body-dementia/basics-lewy-body-dementia

National Institute on Aging. (2015b). Global Health and Aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/global-health-and-aging/living-longer

National Institute on Aging. (2015c). Hearing loss. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/hearing-loss

National Institute on Aging. (2015d). Humanity’s aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/global- health-and-aging/humanitys-aging

National Institute on Aging. (2015e). Shingles. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/shingles

National Institute on Aging. (2015f). Skin care and aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/skin-care- and-aging

National Institute on Aging. (2016). A good night’s sleep. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/good- nights-sleep

National Library of Medicine. (2014). Aging changes in body shape. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003998.htm

National Library of Medicine. (2019). Aging changes in the heart and blood vessels. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004006.htm

National Osteoporosis Foundation. (2016). Preventing fractures. Retrieved from https://www.nof.org/prevention/preventing- fractures/

National Sleep Foundation. (2009). Aging and sleep. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep-topics/aging- and-sleep

Nelson, T. D. (2016). Promoting healthy aging by confronting ageism. American Psychologist, 71(4), 276-282.

Novotney, A. (2019). Social isolation: It could kill you. Monitor on Psychology, 50(5), 33-37.

Office on Women’s Health. (2010a). Raising children again. Retrieved from http://www.womenshealth.gov/aging/caregiving/raising-children-again.html

Office on Women’s Health. (2010b). Sexual health. Retrieved from http://www.womenshealth.gov/aging/sexual-health/

Olanow, C. W., & Tatton, W. G. (1999). Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 22, 123-144.

Ortman, J. M., Velkoff, V. A., & Hogan, H. (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States. United States Census. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

Overstreet, L. (2006). Unhappy birthday: Stereotypes in late adulthood. Unpublished manuscript, Texas Woman’s University.

Owsley, C., Rhodes, L. A., McGwin Jr., G., Mennemeyer, S. T., Bregantini, M., Patel, N., … Girkin, C. A. (2015). Eye care quality and accessibility improvement in the community (EQUALITY) for adults at risk for glaucoma: Study rationale and design. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 1-14. DOI 10:1186/s12939-015-0213-8

Papernow, P. L. (2018). Recoupling in midlife and beyond: From love at last to not so fast. Family Processes, 57(1), 52-69. Park, D. C. & Gutchess, A. H. (2000). Cognitive aging and everyday life. In D.C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive Aging: A Primer (pp. 217–232). New York: Psychology Press.

Park, D. C., & Reuter-Lorenz, P. (2009). The adaptive brain: Aging and neurocognitive scaffolding. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 173-196.

Pew Research Center. (2011). Fighting poverty in a tough economy. Americans move in with their relatives. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files.2011/10.Multigenerationsl-Households-Final1.pdf

Pilkington, P. D., Windsor, T. D., & Crisp, D. A. (2012). Volunteerism and subjective well-being in midlife and older adults: The role of supportive social networks. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 67 B (2), 249- 260. Doi:10.1093/geronb/grb154.

Quinn, J. F., & Cahill, K. E. (2016). The new world of retirement income security in America. American Psychologist, 71(4), 321-333.

Resnikov, S., Pascolini, D., Mariotti, S. P., & Pokharel, G. P. (2004). Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82, 844-851.

Rhodes, M. G., Castel, A. D., & Jacoby, L. L. (2008). Associative recognition of face pairs by younger and older adults: The role of familiarity-based processing. Psychology and Aging, 23, 239-249.

Riediger, M., Freund, A.M., & Baltes, P.B. (2005). Managing life through personal goals: Intergoal facilitation and intensity of goal pursuit in younger and older adulthood. Journals of Gerontology, 60B, P84-P91.

Roberto, K. A. (2016). The complexities of elder abuse. American Psychologist, 71(4), 302-311.

Robin, R. C. (2010). Grown-up, but still irresponsible. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/10weekinreview/10rabin.html>.

Robins, R.W., & Trzesniewski, K.H. (2005). Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 (3), 158-162. DOI: 10.1111/j.0963- 7214.2005.00353x

Rowe, J. W. & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440.

Rubinstein, R.L. (2002). The third age. In R.S. Weiss & S.A. Bass (Eds.), Challenges of the third age; Meaning and purpose in later life (pp. 29-40). New York: Oxford University Press.

Ruckenhauser, G., Yazdani, F., & Ravaglia, G. (2007). Suicide in old age: Illness or autonomous decision of the will? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 44(6), S355-S358.

Saiidi, U. (2019). US life expectancy has been declining. Here’s why. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2019/07/09/us-life- expectancy-has-been-declining-heres-why.html

Salthouse, T. A. (1984). Effects of age and skill in typing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113, 345.

Salthouse, T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103, 403-428. Salthouse, T. A. (2004). What and when of cognitive aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(4), 140-144.