Chapter 24: Psychosocial Development in Early Adulthood

Chapter 24 Learning Objectives

- Describe the relationship between infant and adult temperament

- Explain personality in early adulthood

- Explain the five factor model of personality

- Describe adult attachment styles

- Describe Erikson’s stage of intimacy vs. isolation

- Identify the factors affecting attraction

- Differentiate among the types of love

- Describe adult lifestyles, including singlehood, cohabitation, and marriage

- Describe the factors that influence parenting

Temperament and Personality in Adulthood

If you remember from chapter 3, temperament is defined as the innate characteristics of the infant, including mood, activity level, and emotional reactivity, noticeable soon after birth. Does one’s temperament remain stable throughout the lifespan? Do shy and inhibited babies grow up to be shy adults, while the sociable child continues to be the life of the party? Like most developmental research the answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no. Chess and Thomas (1987), who identified children as easy, difficult, slow-to-warm-up or blended, found that children identified as easy grew up to became well-adjusted adults, while those who exhibited a difficult temperament were not as well-adjusted as adults. Kagan (2002) studied the temperamental category of inhibition to the unfamiliar in children. Infants exposed to unfamiliarity reacted strongly to the stimuli and cried loudly, pumped their limbs, and had an increased heart rate. Research has indicated that these highly reactive children show temperamental stability into early childhood, and Bohlin and Hagekull (2009) found that shyness in infancy was linked to social anxiety in adulthood.

An important aspect of this research on inhibition was looking at the response of the amygdala, which is important for fear and anxiety, especially when confronted with possible threatening events in the environment. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRIs) young adults identified as strongly inhibited toddlers showed heightened activation of the amygdala when compared to those identified as uninhibited toddlers (Davidson & Begley, 2012).

The research does seem to indicate that temperamental stability holds for many individuals through the lifespan, yet we know that one’s environment can also have a significant impact. Recall from our discussion on epigenesis or how environmental factors are thought to change gene expression by switching genes on and off. Many cultural and environmental factors can affect one’s temperament, including supportive versus abusive child-rearing, socioeconomic status, stable homes, illnesses, teratogens, etc. Additionally, individuals often choose environments that support their temperament, which in turn further strengthens them (Cain, 2012). In summary, because temperament is genetically driven, genes appear to be the major reason why temperament remains stable into adulthood. In contrast, the environment appears mainly responsible for any change in temperament (Clark & Watson, 1999).

Everybody has their own unique personality; that is, their characteristic manner of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others (John, Robins, & Pervin, 2008). Personality traits refer to these characteristics, routine ways of thinking, feeling, and relating to others. Personality integrates one’s temperament with cultural and environmental influences. Consequently, there are signs or indicators of these traits in childhood, but they become particularly evident when the person is an adult. Personality traits are integral to each person’s sense of self, as they involve what people value, how they think and feel about things, what they like to do, and, basically, what they are like most every day throughout much of their lives.

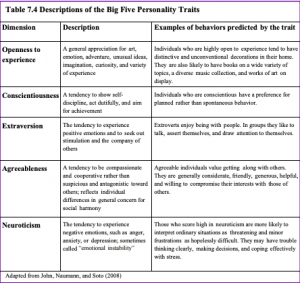

Table 7.4

Five-Factor Model: There are hundreds of different personality traits, and all of these traits can be organized into the broad dimensions referred to as the Five-Factor Model (John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008). These five broad domains include Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (Think OCEAN to remember). This applies to traits that you may use to describe yourself. Table 7.4 provides illustrative traits for low and high scores on the five domains of this model of personality.

Does personality change throughout adulthood? Previously the answer was no, but contemporary research shows that although some people’s personalities are relatively stable over time, others’ are not (Lucas & Donnellan, 2011; Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). Longitudinal studies reveal average changes during adulthood in the expression of some traits (e.g., neuroticism and openness decrease with age and conscientiousness increases) and individual differences in these patterns due to idiosyncratic life events (e.g., divorce, illness). Longitudinal research also suggests that adult personality traits, such as conscientiousness, predict important life outcomes including job success, health, and longevity (Friedman et al., 1993; Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007).

The Harvard Health Letter (2012) identifies research correlations between conscientiousness and lower blood pressure, lower rates of diabetes and stroke, fewer joint problems, being less likely to engage in harmful behaviors, being more likely to stick to healthy behaviors, and more likely to avoid stressful situations. Conscientiousness also appears related to career choices, friendships, and stability of marriage. Lastly, a person possessing both self-control and organizational skills, both related to conscientiousness, may withstand the effects of aging better and have stronger cognitive skills than one who does not possess these qualities.

Attachment in Young Adulthood

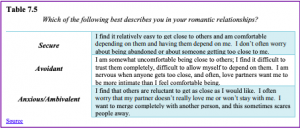

Hazan and Shaver (1987) described the attachment styles of adults, using the same three general categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children: secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent. Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about romantic relationships they were in and select the paragraph that best described the way they felt, thought, and behaved in these relationships (See Table 7.5).

Table 7.5

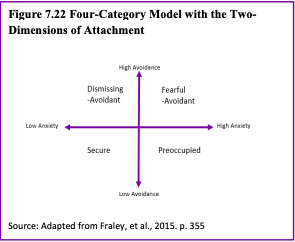

Bartholomew (1990) challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and suggested that adult attachment was best described as varying along two dimensions; attachment related-anxiety and attachment-related avoidance. Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner really loves them. Those who score high on this dimension fear that their partner will reject or abandon them (Fraley, Hudson, Heffernan, & Segal, 2015). Attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others, and whether they trust and feel they can depend on others. Those who score high on attachment-related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their sense of autonomy (Fraley et al., 2015). According to Bartholomew (1990) this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults; secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful-avoidant (see Figure 7.22)

Figure 7.22

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety, but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves but do not trust others, thus they do not share their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance, but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful-avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships, but do not feel comfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their own social skills in maintaining relationships.

Research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

- Adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships (Butzer, & Campbell, 2008; Holland, Fraley, & Roisman, 2012).

- Those high in attachment-related anxiety report more daily conflict in their relationships (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Kashy, 2005).

- Those with avoidant attachment exhibit less support to their partners (Simpson, Rholes, Oriña, & Grich, 2002).

- Young adults show greater attachment-related anxiety than do middle-aged or older adults (Chopik, Edelstein, & Fraley, 2013).

- Some studies report that young adults show more attachment-related avoidance (Schindler, Fagundes, & Murdock, 2010), while other studies find that middle-aged adults show higher avoidance than younger or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013).

- Young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents make the transition to adulthood more easily than do those with more insecure attachments (Fraley, 2013).

- Young adults with secure attachments and authoritative parents were less likely to be depressed than those with authoritarian or permissive parents or who experienced an avoidant or ambivalent attachment (Ebrahimi, Amiri, Mohamadlou, & Rezapur, 2017).

Do people with certain attachment styles attract those with similar styles? When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioral qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding, that is the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver (Chappell & Davis, 1998). However, we know that people do not always end up with others who meet their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners, and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.” Frazier, Byer, Fischer, Wright, and DeBord (1996) studied the attachment patterns of more than 83 heterosexual couples and found that, if the man was relatively secure, the woman was also likely to be secure.

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are higher insecurity than those who are more insecure (McClure, Lydon, Baccus, & Baldwin, 2010). However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships. For example, in a longitudinal study, Hudson, Fraley, Vicary, and Brumbaugh (2012) found that, if one person in a relationship experienced a change in security, his or her partner was likely to experience a change in the same direction.

Do early experiences as children shape adult attachment? The majority of research on this issue is retrospective; that is, it relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). A number of longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood. For example, Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Owen, and Holland (2013) found in a sample of more than 700 individuals studied from infancy to adulthood that maternal sensitivity across development prospectively predicted security at age 18. Simpson, Collins, Tran, and Haydon (2007) found that attachment security, assessed in infancy in the strange situation, predicted peer competence in grades one to three, which, in turn, predicted the quality of friendship relationships at age 16, which, in turn, predicted the expression of positive and negative emotions in their adult romantic relationships at ages 20 to 23.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear, attachment theorists assume that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development, but that does not mean that attachment patterns are set in stone. In short, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships through a number of corrective experiences, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of his or her early experiences alone. Those early experiences are considered important, not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

Relationships with Parents and Siblings

In early adulthood, the parent-child relationship has to transition toward a relationship between two adults. This involves a reappraisal of the relationship by both parents and young adults.

One of the biggest challenges for parents, especially during emerging adulthood, is coming to terms with the adult status of their children. Aquilino (2006) suggests that parents who are reluctant or unable to do so may hinder young adults’ identity development. This problem becomes more pronounced when young adults still reside with their parents. Arnett (2004) reported that leaving home often helped promote psychological growth and independence in early adulthood.

Sibling relationships are one of the longest-lasting bonds in people’s lives. Yet, there is little research on the nature of sibling relationships in adulthood (Aquilino, 2006). What is known is that the nature of these relationships change, as adults have a choice as to whether they will maintain a close bond and continue to be a part of the life of a sibling. Siblings must make the same reappraisal of each other as adults, as parents have to with their adult children. Research has shown a decline in the frequency of interactions between siblings during early adulthood, as presumably peers, romantic relationships, and children become more central to the lives of young adults. Aquilino (2006) suggests that the task in early adulthood may be to maintain enough of a bond so that there will be a foundation for this relationship in later life. Those who are successful can often move away from the “older-younger” sibling conflicts of childhood, toward a more equal relationship between two adults. Siblings that were close to each other in childhood are typically close in adulthood (Dunn, 1984, 2007), and in fact, it is unusual for siblings to develop closeness for the first time in adulthood. Overall, the majority of adult sibling relationships are close (Cicirelli, 2009).

Erikson: Intimacy vs. Isolation

Erikson’s (1950, 1968) sixth stage focuses on establishing intimate relationships or risking social isolation. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity.

Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, as there are periods of identity crisis and stability. However, once identity is established intimate relationships can be pursued. These intimate relationships include acquaintanceships and friendships, but also the more important close relationships, which are the long-term romantic relationships that we develop with another person, for instance, in a marriage (Hendrick & Hendrick, 2000).

Factors influencing Attraction

Because most of us enter into a close relationship at some point, it is useful to know what psychologists have learned about the principles of liking and loving. A major interest of psychologists is the study of interpersonal attraction, or what makes people like, and even love, each other.

Similarity: One important factor in attraction is a perceived similarity in values and beliefs between the partners (Davis & Rusbult, 2001). The similarity is important for relationships because it is more convenient if both partners like the same activities and because similarity supports one’s values. We can feel better about ourselves and our choice of activities if we see that our partner also enjoys doing the same things that we do. Having others like and believe in the same things we do makes us feel validated in our beliefs. This is referred to as consensual validation and is an important aspect of why we are attracted to others.

Self-Disclosure: Liking is also enhanced by self-disclosure, the tendency to communicate frequently, without fear of reprisal, and in an accepting and empathetic manner. Friends are friends because we can talk to them openly about our needs and goals and because they listen and respond to our needs (Reis & Aron, 2008). However, self-disclosure must be balanced. If we open up about the concerns that are important to us, we expect our partner to do the same in return. If the self-disclosure is not reciprocal, the relationship may not last.

Proximity: Another important determinant of liking is proximity or the extent to which people are physically near us. Research has found that we are more likely to develop friendships with people who are nearby, for instance, those who live in the same dorm that we do, and even with people who just happen to sit nearer to us in our classes (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2008).

Proximity has its effect on liking through the principle of mere exposure, which is the tendency to prefer stimuli (including, but not limited to people) that we have seen more frequently. The effect of mere exposure is powerful and occurs in a wide variety of situations. Infants tend to smile at a photograph of someone they have seen before more than they smile at a photograph of someone they are seeing for the first time (Brooks-Gunn & Lewis, 1981), and people prefer side-to-side reversed images of their own faces over their normal (nonreversed) face, whereas their friends prefer their normal face over the reversed one (Mita, Dermer, & Knight, 1977). This is expected on the basis of mere exposure since people see their own faces primarily in mirrors, and thus are exposed to the reversed face more often.

Mere exposure may well have an evolutionary basis. We have an initial fear of the unknown, but as things become familiar, they seem more similar and safer, and thus produce more positive affect and seem less threatening and dangerous (Harmon-Jones & Allen, 2001; Freitas, Azizian, Travers, & Berry, 2005). When the stimuli are people, there may well be an added effect. Familiar people become more likely to be seen as part of the ingroup rather than the outgroup, and this may lead us to like them more. Zebrowitz and her colleagues found that we like people of our own race in part because they are perceived as similar to us (Zebrowitz, Bornstad, & Lee, 2007).

Friendships

In our twenties, intimacy needs may be met in friendships rather than with partners. This is especially true in the United States today as many young adults postpone making long-term commitments to partners, either in marriage or in cohabitation. The kinds of friendships shared by women tend to differ from those shared by men (Tannen, 1990). Friendships between men are more likely to involve sharing information, providing solutions, or focusing on activities rather than discussion problems or emotions. Men tend to discuss opinions or factual information or spend time together in an activity of mutual interest. Friendships between women are more likely to focus on sharing weaknesses, emotions, or problems. Women talk about difficulties they are having in other relationships and express their sadness, frustrations, and joys. These differences in approaches lead to problems when men and women come together. She may want to vent about a problem she is having; he may want to provide a solution and move on to some activity. But when he offers a solution, she thinks he does not care. Friendships between men and women become more difficult because of the unspoken question about whether friendships will lead to romantic involvement. Consequently, friendships may diminish once a person has a partner or single friends may be replaced with a couple of friends.

Love

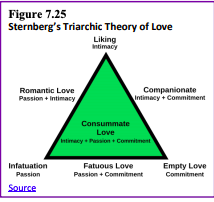

Sternberg (1988) suggests that there are three main components of love: Passion, intimacy, and commitment (see Figure 7.25). Love relationships vary depending on the presence or absence of each of these components. Passion refers to the intense, physical attraction partners feel toward one another. Intimacy involves the ability the share feelings, psychological closeness and personal thoughts with the other. Commitment is the conscious decision to stay together. Passion can be found in the early stages of a relationship, but intimacy takes time to develop because it is based on the knowledge of the partner. Once intimacy has been established, partners may resolve to stay in the relationship. Although many would agree that all three components are important to a relationship, many love relationships do not consist of all three. Let’s look at other possibilities.

Liking: In this relationship, intimacy or knowledge of the other and a sense of closeness is present. Passion and commitment, however, are not. Partners feel free to be themselves and disclose personal information. They may feel that the other person knows them well and can be honest with them and let them know if they think the person is wrong. These partners are friends. However, being told that your partner “thinks of you as a friend” can be a devastating blow if you are attracted to them and seeking a romantic involvement.

Infatuation: Perhaps, this is Sternberg’s version of “love at first sight”. Infatuation consists of an immediate, intense physical attraction to someone. A person who is infatuated finds it hard to think of anything but the other person. Brief encounters are played over and over in one’s head; it may be difficult to eat and there may be a rather constant state of arousal. Infatuation is rather short-lived, however, lasting perhaps only a matter of months or as long as a year or so. It tends to be based on physical attraction and an image of what one “thinks” the other is all about.

Fatuous Love: However, some people who have a strong physical attraction push for commitment early in the relationship. Passion and commitment are aspects of fatuous love. There is no intimacy and the commitment is premature. Partners rarely talk seriously or share their ideas. They focus on their intense physical attraction and yet one, or both, is also talking of making a lasting commitment. Sometimes this is out of a sense of insecurity and a desire to make sure the partner is locked into the relationship.

Empty Love: This type of love may be found later in a relationship or in a relationship that was formed to meet needs other than intimacy or passion, including financial needs, childrearing assistance, or attaining/maintaining status. Here the partners are committed to staying in the relationship for the children, because of a religious conviction, or because there are no alternatives. However, they do not share ideas or feelings with each other and have no physical attraction for one another.

Romantic Love: Intimacy and passion are components of romantic love, but there is no commitment. The partners spend much time with one another and enjoy their closeness, but have not made plans to continue. This may be true because they are not in a position to make such commitments or because they are looking for passion and closeness and are afraid it will die out if they commit to one another and start to focus on other kinds of obligations.

Companionate Love: Intimacy and commitment are the hallmarks of companionate love. Partners love and respect one another and they are committed to staying together. However, their physical attraction may have never been strong or may have just died out over time. Nevertheless, partners are good friends and committed to one another.

Consummate Love: Intimacy, passion, and commitment are present in consummate love. This is often perceived by western cultures as “the ideal” type of love. The couple shares passion; the spark has not died, and the closeness is there. They feel like best friends, as well as lovers, and they are committed to staying together.

Adult Lifestyles

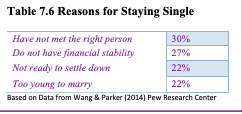

Singlehood: Being single is the most common lifestyle for people in their early 20s, and there has been an increase in the number of adults staying single. In 1960, only about 1 in 10 adults age 25 or older had never been married, in 2012 that had risen to 1 in 5 (Wang & Parker, 2014). While just over half (53%) of unmarried adults say they would eventually like to get married, 32 percent are not sure, and 13 percent do not want to get married. It is projected that by the time current young adults reach their mid-40s and 50s, almost 25% of them may not have married. The U.S. is not the only country to see a rise in the number of single adults.

Table 7.6 lists some of the reasons young adults give for staying single. In addition, adults are marrying later in life, cohabitating, and raising children outside of marriage in greater numbers than in previous generations. Young adults also have other priorities, such as education, and establishing their careers. This may be reflected by changes in attitudes about the importance of marriage. In a recent Pew Research survey of Americans, respondents were asked to indicate which of the following statements came closer to their own views:

- “Society is better off if people make marriage and having children a priority.”

- “Society is just as well off if people have priorities other than marriage and children”

Slightly more adults endorsed the second statement (50%) than those who chose the first (46%), with the remainder either selecting neither, both equally or not responding (Wang & Parker, 2014). Young adults age 18-29 were more likely to endorse this view than adults age 30 to 49; 67 percent and 53 percent respectively. In contrast, those aged 50 or older were more likely to endorse the first statement (53 percent).

Hooking Up: United States demographic changes have significantly affected the romantic relationships among emerging and early adults. As previously described, the age for puberty has declined, while the times for one’s first marriage and first child have been pushed to older ages. This results in a “historically unprecedented time gap where young adults are physiologically able to reproduce, but not psychologically or socially ready to settle down and begin a family and child-rearing,” (Garcia, Reiber, Massey, & Merriwether, 2012, p. 172). Consequently, according to Bogle (2007, 2008) traditional forms of dating have shifted to more casual hookups that involve uncommitted sexual encounters.

Even though most research on hooking up involves college students, 70% of sexually active 12- 21-year-olds reported having had uncommitted sex during the past year (Grello, Welsh, Harper, & Dickson, 2003). Additionally, Manning, Giordano, and Longmore (2006) found that 61% of sexually active seventh, ninth, and eleventh graders reported being involved in a sexual encounter outside of a dating relationship.

Friends with Benefits: Hookups are different than those relationships that involve continued mutual exchange. These relationships are often referred to as Friends with Benefits (FWB) or “Booty Calls.” These relationships involve friends having casual sex without commitment.

Hookups do not include a friendship relationship. Bisson and Levine (2009) found that 60% of 125 undergraduates reported a FWB relationship. The concern with FWB is that one partner may feel more romantically invested than the other (Garcia et al., 2012).

Hooking up Gender Differences: When asked about their motivation for hooking up, both males and females indicated physical gratification, emotional gratification, and a desire to initiate a romantic relationship as reasons (Garcia & Reiber, 2008). Although males and females are more similar than different in their sexual behaviors, a consistent finding among the research is that males demonstrate a greater permissiveness to casual sex (Oliver & Hyde, 1993). In another study involving 16,288 individuals across 52 nations, males reported a greater desire of sexual partner variety than females, regardless of relationship status or sexual orientation (Schmitt et al., 2003). This difference can be attributed to gender role expectations for both males and females regarding sexual promiscuity. Additionally, the risks of sexual behavior are higher for females and include unplanned pregnancy, increased sexually transmitted diseases, and susceptibility to sexual violence (Garcia et al., 2012).

Although hooking up relationships have become normalized for emerging adults, some research indicates that the majority of both sexes would prefer a more traditional romantic relationship (Garcia et al., 2012). Additionally, Owen and Fincham (2011) surveyed 500 college students with experience with hookups, and 65% of women and 45% of men reported that they hoped their hookup encounter would turn into a committed relationship. Further, 51% of women and 42% of men reported that they tried to discuss the possibility of starting a relationship with their hookup partner. Casual sex has also been reported to be the norm among gay men, but they too indicate a desire for romantic and companionate relationships (Clarke & Nichols, 1972).

Emotional Consequences of Hooking up: Concerns regarding hooking up behavior certainly are evident in the research literature. One significant finding is the high comorbidity of hooking up and substance use. Those engaging in non-monogamous sex are more likely to have used marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, and the overall risks of sexual activity are drastically increased with the addition of alcohol and drugs (Garcia et al., 2012). Regret has also been expressed, and those who had the most regret after hooking up also had more symptoms of depression (Welsh, Grello, & Harper, 2006). Hookups were also found to lower self-esteem, increase guilt, and foster feelings of using someone or feeling used. Females displayed more negative reactions than males, and this may be due to females identifying more emotional involvement in sexual encounters than males.

Hooking up can best be explained by a biological, psychological, and social perspective. Research indicates that emerging adults feel it is necessary to engage in hooking up behavior as part of the sexual script depicted in the culture and media. Additionally, they desire sexual gratification. However, they also want a more committed romantic relationship and may feel regret with uncommitted sex.

Online Dating: The ways people are finding love has changed with the advent of the Internet. Nearly 50 million Americans have tried an online dating website or mobile app (Bryant & Sheldon, 2017). Online dating has also increased dramatically among those aged 18 to 24. Today, one in five emerging adults report using a mobile dating app, while in 2013 only 5% did, and 27% report having used online dating, almost triple the rate in 2013 (Smith & Anderson, 2016).

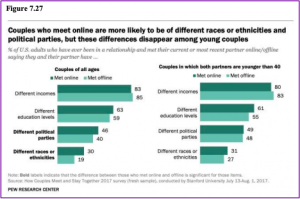

As Finkel, Burnette, and Scissors (2007) found, social networking sites and the Internet perform three important tasks. Specifically, sites provide individuals with access to a database of other individuals who are interested in meeting someone. Dating sites generally reduce issues of proximity, as individuals do not have to be close in proximity to meet. Also, they provide a medium in which individuals can communicate with others. Finally, some Internet dating websites advertise special matching strategies, based on factors such as personality, hobbies, and interests, to identify the “perfect match” for people looking for love online. Social networking sites have provided opportunities for meeting others you would not have normally met. According to a recent survey of couples who met online versus offline (Brown, 2019), those who met online tended to have slightly different levels of education, and political views from their partners, but, the biggest difference was that they were much more likely to come from different racial and ethnic backgrounds (see Figure 7.27). This is not surprising as the average age of the couples who met online was 36, while the average age of couples who met offline was 51. Young adults are more likely to a relationship with people who are different from them, regardless of how they met.

However, social networking sites can also be forums for unsuspecting people to be duped, as the person may not be who he or she says.

Online communication differs from face-to-face interaction in a number of ways. In face-to-face meetings, people have many cues upon which to base their first impressions. A person’s looks, voice, mannerisms, dress, scent, and surroundings all provide information in face-to-face meetings, but in computer-mediated meetings, written messages are the only cues provided. Fantasy is used to conjure up images of voice, physical appearance, mannerisms, and so forth. The anonymity of online involvement makes it easier to become intimate without fear of interdependence. When online, people tend to disclose more intimate details about themselves more quickly. A shy person can open up without worrying about whether or not the partner is frowning or looking away. Someone who has been abused may feel safer in virtual relationships. It is easier to tell one’s secrets because there is little fear of loss. One can find a virtual partner who is warm, accepting, and undemanding (Gwinnell, 1998), and exchanges can be focused more on emotional attraction than physical appearance.

To evaluate what individuals are looking for online, Menkin, Robles, Wiley and Gonzaga (2015) reviewed data from an eHarmony.com relationship questionnaire completed by a cross-sectional representation of 5,434 new users. Their results indicated that users consistently valued communication and characteristics, such as personality and kindness over sexual attraction.

Females valued communication over sexual attraction, even more when compared to males, and older users rated sexual attraction as less important than younger users. Alterovitz and Mendelsohn (2011) analyzed 600 Internet personal ads across the lifespan and found that men sought physical attractiveness and offered status-related information more than women, while women were more selective than men and sought status more than men. These findings were consistent with previous research on gender differences regarding the importance of physical/sexual attraction.

Catfishing and other forms of scamming is an increasing concern for those who use dating and social media sites and apps. Catfishing refers to “a deceptive activity involving the creation of a fake online profile for deceptive purposes” (Smith, Smith, & Blazka, 2017, p. 33). Notre Dame University linebacker Manti Ta’o fell victim to a catfishing scam. The young woman “Kekua” who he had struck up an online relationship with was a hoax, and he was not the first person to have been scammed by this fictitious woman. A number of US states have passed legislation to address online impersonation, from stealing the information and creating a fake account of a real person to the creation of a fictitious persona with the intent to defraud or harm others (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2017).

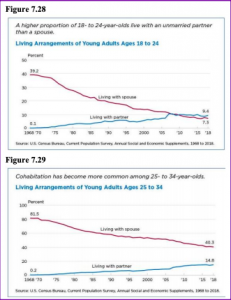

Cohabitation: In American society, as well as in a number of other cultures, cohabitation has become increasingly commonplace (Gurrentz, 2018). For many emerging adults, cohabitation has become more commonplace than marriage, as can be seen in Figures 7.28. While marriage is still a more common living arrangement for those 25-34, cohabitation has increased, while marriage has declined, as can be seen in Figure 7.29. Gurrentz also found that cohabitation varies by socioeconomic status. Those who are married tend to have higher levels of education, and thus higher earnings, or earning potential.

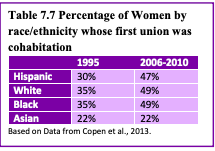

Copen, Daniels, and Mosher (2013) found that from 1995 to 2010 the median length of the cohabitation relationship had increased regardless of whether the relationship resulted in marriage, remained intact, or had since dissolved. In 1995 the median length of the cohabitation relationship was 13 months, whereas it was 22 months by 2010. Cohabitation for all racial/ethnic groups, except for Asian women increased between 1995 and 2010 (see Table 7.7). Forty percent of the cohabitations transitioned into marriage within three years, 32% were still cohabitating, and 27% of cohabitating relationships had dissolved within the three years.

Three explanations have been given for the rise of cohabitation in Western cultures. The first notes that the increase in individualism and secularism, and the resulting decline in religious observance, has led to greater acceptance and adoption of cohabitation (Lesthaeghe & Surkyn, 1988). Moreover, the more people view cohabitating couples, the more normal this relationship becomes, and the more couples who will then cohabitate. Thus, cohabitation is both a cause and the effect of greater cohabitation.Three explanations have been given for the rise of cohabitation in Western cultures. The first notes that the increase in individualism and secularism, and the resulting decline in religious observance, has led to greater acceptance and adoption of cohabitation (Lesthaeghe & Surkyn, 1988).

A second explanation focuses on economic changes. The growth of industry and the modernization of many cultures have improved women’s social status, leading to greater gender equality and sexual freedom, with marriage, no longer being the only long-term relationship option (Bumpass, 1990). A final explanation suggests that the change in employment requirements, with many jobs now requiring more advanced education, has led to a competition between marriage and pursuing post-secondary education (Yu & Xie, 2015). This might account for the increase in the age of first marriage in many nations. Taken together, the greater acceptance of premarital sex, and the economic and educational changes would lead to a transition in relationships. Overall, cohabitation may become a step in the courtship processor may, for some, replace marriage altogether.

Similar increases in cohabitation have also occurred in other industrialized countries. For example, rates are high in Great Britain, Australia, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. In fact, more children in Sweden are born to cohabiting couples than married couples. The lowest rates of cohabitation in industrialized countries are in Ireland, Italy, and Japan (Benokraitis, 2005).

Cohabitation in Non-Western Cultures, The Philippines and China: Similar to other nations, young people in the Philippines are more likely to delay marriage, to cohabitate, and to engage in premarital sex as compared to previous generations (Williams, Kabamalan, & Ogena, 2007).

Despite these changes, many young people are still not in favor of these practices. Moreover, there is still a persistence of traditional gender norms as there are stark differences in the acceptance of sexual behavior out of wedlock for men and women in Philippine society. Young men are given greater freedom. In China, young adults are cohabitating in higher numbers than in the past (Yu & Xie, 2015). Unlike many Western cultures, in China adults with higher, rather than lower, levels of education are more likely to cohabitate. Yu and Xie suggest this may be due to seeing cohabitation as being a more “innovative” behavior and that those who are more highly educated may have had more exposure to Western culture.

Marriage Worldwide: Cohen (2013) reviewed data assessing most of the world’s countries and found that marriage has declined universally during the last several decades. This decline has occurred in both poor and rich countries, however, the countries with the biggest drops in marriage were mostly rich: France, Italy, Germany, Japan, and the U.S. Cohen states that the decline is not only due to individuals delaying marriage but also because of high rates of non- marital cohabitation. Delayed or reduced marriage is associated with higher income and lower fertility rates that are reflected worldwide.

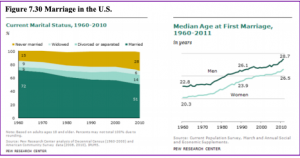

Marriage in the United States: In 1960, 72% of adults age 18 or older were married, in 2010 this had dropped to barely half (Wang & Taylor, 2011). At the same time, the age of first marriage has been increasing for both men and women. In 1960, the average age for first marriage was 20 for women and 23 for men. By 2010 this had increased to 26.5 for women and nearly 29 for men (see Figure 7.30). Many of the explanations for increases in singlehood and cohabitation previously given can also account for the drop and delay in marriage.

Same-Sex Marriage: On June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution guarantees same-sex marriage. The decision indicated that limiting marriage to only heterosexual couples violated the 14th amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. This ruling occurred 11 years after same-sex marriage was first made legal in Massachusetts, and at the time of the high court decision, 36 states and the District of Columbia had legalized same-sex marriage. Worldwide, 29 countries currently have national laws allowing gays and lesbians to marry (Pew Research Center, 2019). As can be seen in Table 7.8, these countries are located mostly in Europe and the Americas.

Cultural Influences on Marriage: Many cultures have both explicit and unstated rules that specify who is an appropriate mate. Consequently, mate selection is not completely left to the individual. Rules of endogamy indicate the groups we should marry within and those we should not marry in (Witt, 2009). For example, many cultures specify that people marry within their own race, social class, age group, or religion. Endogamy reinforces the cohesiveness of the group. Additionally, these rules encourage homogamy or marriage between people who share social characteristics. The majority of marriages in the U. S. are homogamous with respect to race, social class, age and to a lesser extent, religion. Homogamy is also seen in couples with similar personalities and interests.

Arranged Marriages and Elopement: Historically, marriage was not a personal choice, but one made by one’s family. Arranged marriages often ensured proper transference of a family’s wealth and the support of ethnic and religious customs. Such marriages were a marriage of families rather than of individuals. In Western Europe, starting in the 18th century the notion of personal choice in a marital partner slowly became the norm. Arranged marriages were seen as “traditional” and marriages based on love “modern”. Many of these early “love” marriages were obtained by eloping (Thornton, 2005).

Around the world, more and more young couples are choosing their partners, even in nations where arranged marriages are still the norm, such as India and Pakistan. Desai and Andrist (2010) found that only 5% of the women surveyed, aged 25-49, had a primary role in choosing their partner. Only 22% knew their partner for more than one month before they were married. However, the younger cohort of women was more likely to have been consulted by their families before their partner was chosen than were the older cohort, suggesting that family views are changing about personal choice. Allendorf (2013) reports that this 5% figure may also underestimate young people’s choice, as only women were surveyed. Many families in India are increasingly allowing sons to veto power over the parents’ choice of his future spouse, and some families give daughters the same say.

Marital Arrangements in India: As the number of arranged marriages in India is declining, elopement is increasing. Allendorf’s (2013) study of a rural village in India, describes the elopement process. In many cases, the female leaves her family home and goes to the male’s home, where she stays with him and his parents. After a few days, a member of his family will inform her family of her whereabouts and gain consent for the marriage. In other cases, where the couple anticipates some degree of opposition to the union, the couple may run away without the knowledge of either family, often going to a relative of the male. After a few days, the couple comes back to the home of his parents, where at that point consent is sought from both families. Although, in some cases, families may sever all ties with their child or encourage him or her to abandon the relationship, typically, they agree to the union as the couple has spent time together overnight. Once consent has been given, the couple lives with his family and are considered married. A more formal ceremony takes place a few weeks or months later.

Arranged marriages are less common in the more urban regions of India than they are outside of the cities. In rural regions, often the family farm is the young person’s only means of employment. Thus, going against family choices may carry bigger consequences. Young people who live in urban centers have more employment options. As a result, they are often less economically dependent on their families and may feel freer to make their own choices. Thornton (2005) suggests these changes are also being driven by mass media, international travel, and general Westernization of ideas. Besides India, China, Nepal, and several nations in Southeast Asia have seen a decline in the number of arranged marriages, and an increase in elopement or couples choosing their own partners with their families’ blessings (Allendorf, 2013).

Predictors of Marital Harmony: Advice on how to improve one’s marriage is centuries old. One of today’s experts on marital communication is John Gottman. Gottman (1999) differs from many marriage counselors in his belief that having a good marriage does not depend on compatibility. Rather, the way that partners communicate with one another is crucial. At the University of Washington in Seattle, Gottman has measured the physiological responses of thousands of couples as they discuss issues of disagreement. Fidgeting is one’s chair, leaning closer to or further away from the partner while speaking, and increases in respiration and heart rate are all recorded and analyzed along with videotaped recordings of the partners’ exchanges. Gottman believes he can accurately predict whether or not a couple will stay together by analyzing their communication. In marriages destined to fail, partners engage in the “marriage killers”: Contempt, criticism, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Each of these undermines the politeness and respect that healthy marriages require. Stonewalling, or shutting someone out, is the strongest sign that a relationship is destined to fail.

Gottman, Carrere, Buehlman, Coan, and Ruckstuhl (2000) researched the perceptions newlyweds had about their partner and marriage. The Oral History Interview used in the study, which looks at eight variables in marriage including Fondness/affection, we-ness, expansiveness/ expressiveness, negativity, disappointment, and three aspects of conflict resolution (chaos, volatility, glorifying the struggle), was able to predict the stability of the marriage with 87% accuracy at the four to six year-point and 81% accuracy at the seven to nine year-point. Gottman (1999) developed workshops for couples to strengthen their marriages based on the results of the Oral History Interview. Interventions include increasing the positive regard for each other, strengthening their friendship, and improving communication and conflict resolution patterns.

Accumulated Positive Deposits: When there is a positive balance of relationship deposits this can help the overall relationship in times of conflict. For instance, some research indicates that a husband’s level of enthusiasm in everyday marital interactions was related to a wife’s affection in the midst of conflict (Driver & Gottman, 2004), showing that being pleasant and making deposits can change the nature of the conflict. Also, Gottman and Levenson (1992) found that couples rated as having more pleasant interactions, compared with couples with less pleasant interactions, reported marital problems as less severe, higher marital satisfaction, better physical health, and less risk for divorce. Finally, Janicki, Kamarck, Shiffman, and Gwaltney (2006) showed that the intensity of conflict with a spouse predicted marital satisfaction unless there was a record of positive partner interactions, in which case the conflict did not matter as much.

Again, it seems as though having a positive balance through prior positive deposits helps to keep relationships strong even in the midst of conflict.

Intimate Partner Abuse

Violence in romantic relationships is a significant concern for women in early adulthood as females aged 18 to 34 generally experience the highest rates of intimate partner violence.

According to the most recent Violence Policy Center (2018) study, more than 1,800 women were murdered by men in 2016. The study found that nationwide, 93% of women killed by men were murdered by someone they knew, and guns were the most common weapon used. The national rate of women murdered by men in single victim/single offender incidents dropped 24%, from 1.57 per 100,000 in 1996 to 1.20 per 100,000 in 2016. However, since reaching a low of 1.08 per 100,000 women in 2014, the 2016 rate increased by 11%.

Intimate partner violence is often divided into situational couple violence, which is the violence that results when heated conflict escalates, and intimate terrorism, in which one partner consistently uses fear and violence to dominate the other (Bosson, et al., 2019). Men and women equally use and experience situational couple violence, while men are more likely to use intimate terrorism than are women. Consistent with this, a national survey described below, found that female victims of intimate partner violence experience different patterns of violence, such as rape, severe physical violence, and stalking than male victims, who most often experienced more slapping, shoving, and pushing.

The last National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) was conducted in 2015 (Smith et al., 2018). The NISVS examines the prevalence of intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and stalking among women and men in the United States over the respondent’s lifetime and during the 12 months before the interview. A total of 5,758 women and 4,323 men completed the survey. Based on the results, women are disproportionately affected by intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and stalking. Results included:

- Nearly 1 in 3 women and 1 in 6 men experienced some form of contact sexual violence during their lifetime.

- Nearly 1 in 5 women and 1 in 39 men have been raped in their lifetime.

- Approximately 1 in 6 women and 1 in 10 men experienced sexual coercion (e.g., sexual pressure from someone in authority, or being worn down by requests for sex).

- Almost 1 in 5 women have been the victim of severe physical violence by an intimate partner, while 1 in 7 men have experienced the same.

- 1 in 6 women has been stalked during their lifetime, compared to 1 in 19 men.

- More than 1 in 4 women and more than 1 in 10 men have experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner and reported significant short- or long-term impacts, such as post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and injury.

- An estimated 1 in 3 women experienced at least one act of psychological aggression by an intimate partner during their lifetime.

- Men and women who experienced these forms of violence were more likely to report frequent headaches, chronic pain, difficulty with sleeping, activity limitations, poor physical health, and poor mental health than men and women who did not experience these forms of violence.

Parenthood

Parenthood is undergoing changes in the United States and elsewhere in the world. Children are less likely to be living with both parents, and women in the United States have fewer children than they did previously. The average fertility rate of women in the United States was about seven children in the early 1900s and has remained relatively stable at 2.1 since the 1970s (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2011; Martinez, Daniels, & Chandra, 2012). Not only are parents having fewer children, but the context of parenthood has also changed. Parenting outside of marriage has increased dramatically among most socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups, although college-educated women are substantially more likely to be married at the birth of a child than are mothers with less education (Dye, 2010).

People are having children at older ages, too. This is not surprising given that many of the age markers for adulthood have been delayed, including marriage, completing education, establishing oneself at work, and gaining financial independence. In 2014 the average age for American first-time mothers was 26.3 years (CDC, 2015a). The birth rate for women in their early 20s has declined in recent years, while the birth rate for women in their late 30s has risen. In 2011, 40% of births were to women ages 30 and older. For Canadian women, birth rates are even higher for women in their late 30s than in their early 20s. In 2011, 52% of births were to women ages 30 and older, and the average first-time Canadian mother was 28.5 years old (Cohn, 2013). Improved birth control methods have also enabled women to postpone motherhood.

Despite the fact that young people are more often delaying childbearing, most 18- to 29-year-olds want to have children and say that being a good parent is one of the most important things in life (Wang & Taylor, 2011).

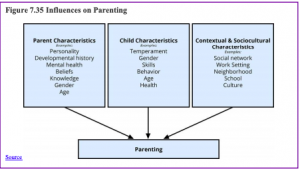

Influences on Parenting: Parenting is a complex process in which parents and children influence on another. There are many reasons that parents behave the way they do. The multiple influences on parenting are still being explored. Proposed influences on parenting include Parent characteristics, child characteristics, and contextual can sociocultural characteristics. (Belsky, 1984; Demick, 1999).

Parent Characteristics: Parents bring unique traits and qualities to the parenting relationship that affect their decisions as parents. These characteristics include the age of the parent, gender, beliefs, personality, developmental history, knowledge about parenting and child development, and mental and physical health. Parents’ personalities affect parenting behaviors. Mothers and fathers who are more agreeable, conscientious, and outgoing are warmer and provide more structure to their children. Parents who are more agreeable, less anxious, and less negative also support their children’s autonomy more than parents who are anxious and less agreeable (Prinzie, Stams, Dekovic, Reijntes, & Belsky, 2009). Parents who have these personality traits appear to be better able to respond to their children positively and provide a more consistent, structured environment for their children.

Parents’ developmental histories, or their experiences as children, also affect their parenting strategies. Parents may learn parenting practices from their own parents. Fathers whose own parents provided monitoring, consistent and age-appropriate discipline, and warmth was more likely to provide this constructive parenting to their own children (Kerr, Capaldi, Pears, & Owen, 2009). Patterns of negative parenting and ineffective discipline also appear from one generation to the next. However, parents who are dissatisfied with their own parents’ approach may be more likely to change their parenting methods with their own children.

Child Characteristics: Parenting is bidirectional. Not only do parents affect their children, but children also influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as gender, birth order, temperament, and health status, affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde, Else-Quest, & Goldsmith, 2004). Thus, child temperament, as previously discussed in chapter 3, is one of the child characteristics that influence how parents behave with their children.

Another child characteristic is the gender of the child. Parents respond differently to boys and girls. Parents often assign different household chores to their sons and daughters. Girls are more often responsible for caring for younger siblings and household chores, whereas boys are more likely to be asked to perform chores outside the home, such as mowing the lawn (Grusec, goodnow, & Cohen, 1996). Parents also talk differently with their sons and daughters, providing more scientific explanations to their sons and using more emotional words with their daughters (Crowley, Callanan, Tenenbaum, & Allen, 2001).

Contextual Factors and Sociocultural Characteristics: The parent-child relationship does not occur in isolation. Sociocultural characteristics, including economic hardship, religion, politics, neighborhoods, schools, and social support, also influence parenting. Parents who experience economic hardship are more easily frustrated, depressed, and sad, and these emotional characteristics affect their parenting skills (Conger & Conger, 2002). Culture also influences parenting behaviors in fundamental ways. Although promoting the development of skills necessary to function effectively in one’s community is a universal goal of parenting, the specific skills necessary vary widely from culture to culture. Thus, parents have different goals for their children that partially depend on their culture (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008). Parents vary in how much they emphasize goals for independence and individual achievements, maintaining harmonious relationships, and being embedded in a strong network of social relationships. Other important contextual characteristics, such as the neighborhood, school, and social networks, also affect parenting, even though these settings do not always include both the child and the parent (Brofenbrenner, 1989). Culture is also a contributing contextual factor, as discussed previously in chapter four. For example, Latina mothers who perceived their neighborhood as more dangerous showed less warmth with their children, perhaps because of the greater stress associated with living a threatening environment (Gonzales et al., 2011). The different influences are shown in Figure 7.35.

References

Allendorf, K. (2013). Schemas of marital change: From arranged marriages to eloping for love. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 453-469.

Alterovitz, S., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2011). Partner preferences across the life span: Online dating by older adults. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1(S), 89-95.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Fifth Edition). Washington, D. C.: Author.

American Psychological Association. (2016). Sexual orientation and homosexuality. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/topics/lgbt/orientation.aspx

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480.

Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transitions to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence to midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8, 133-143.

Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 63–75.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. In J. J. Arnett & N. Galambos (Eds.), Cultural conceptions of the transition to adulthood: New directions in child and adolescent development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Arnett, J. J. (2006). G. Stanley Hall’s adolescence: Brilliance and non-sense. History of Psychology, 9, 186-197. Arnett, J.J. (2007). The long and leisurely route: Coming of age in Europe today. Current History, 106, 130-136.

Arnett, J. J. (2011). Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In L.A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research, and policy (pp. 255–275). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2016). Does emerging adulthood theory apply across social classes? National data on a persistent question. Emerging Adulthood, 4(4), 227-235.

Arnett, J. J., & Taber, S. (1994). Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23, 517–537.

Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193-217). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Babcock, L., Gelfand, M., Small, D., & Stayn, H. (2006). Gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations. In D. De Cremer, M. Zelenberg, & J.K. Muringham (Eds.), Social psychology and economics (pp. 239-262). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2008). Becoming friends by chance. Psychological Science, 19(5), 439–440. Bailey, J. M., & Pillard, R. C. (1991). A genetic study of male sexual orientation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 1089-1096.

Bailey, J. M., Pillard, R. C., Neale, M. C. & Agyei, Y. (1993). Heritable factors influence sexual orientation in women. Archives of General Psychology, 50, 217-223.

Baldridge, D.C., Eddleston, K.A., & Vega, J.F. (2006). Saying no to being uprooted: The impact of family and gender on willingness to relocate. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79, 131-149.

Balthazart, J. (2018). Fraternal birth order effect on sexual orientation explained. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(2), 234-236.

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147-178. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3524.61.2.226.

Basseches, M. (1984). Dialectical thinking and adult development. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Pub.

Bauermeister, J. A., Johns, M. M., Sandfort, T. G., Eisenberg, A., Grossman, A. H., & D’Augelli, A. R. (2010). Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1148-1163.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96.

Benokraitis, N. V. (2005). Marriages and families: Changes, choices, and constraints (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Berger, K. S. (2005). The developing person through the life span (6th ed.). New York: Worth.

Bisson, M. A., & Levine, T. R. (2009). Negotiating a friends with benefits relationship. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 66–73. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9211-2

Blanchard, R. (2001). Fraternal birth order and the maternal immune hypothesis of male homosexuality. Hormones and Behavior, 40, 105-114.

Blau, F. D., Ferber, M. A., & Winkler, A. E. (2010). The economics of women, men and work. (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Prentice Hall.

Bogaert, A. F. (2015). Asexuality: What it is and why it matters. Journal of Sex Research, 52(4), 362-379. doi:10.1080/00224499.2015.1015713

Bogle, K. A. (2007). The shift from dating to hooking up in college: What scholars have missed. Sociology Compass, 1/2, 775– 788.

Bogle, K. A. (2008). Hooking up: Sex, dating, and relationships on campus. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Bohlin, G., & Hagekull, B. (2009). Socio-emotional development from infancy to young adulthood. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 50, 592-601.

Borgogna, N. C., McDermott, R. C., Aita, S. L., & Kridel, M. M. (2019). Anxiety and depression across gender and sexual minorities: Implications for transgender, gender nonconforming, pansexual, demisexual, asexual, queer and questioning individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(1), 54-63.

Bosson, J. K., Vandello, J., & Buckner, C. (2019). The psychology of sex and gender. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Boundless. (2016). Physical development in adulthood. Boundles Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/human-development-14/early-and- middle-adulthood-74/physical-development-in-adulthood-287-12822/

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of Child Development, Vol. 6 (pp. 187–251). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Lewis, M. (1981). Infant social perception: Responses to pictures of parents and strangers. Developmental Psychology, 17(5), 647–649.

Brown, A. (2019). Couples who meet online are more diverse than those who meet in other ways, largely because they’re younger. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/24/couples-who-meet-online-are-more-diverse-than-those-who-meet-in-other-ways-largely-because-theyre-younger/

Bruckmuller, S., Ryan, M.K., Floor, R., & Haslam, S.A. (2014). The glass cliff: Examining why women occupy leadership positions in precarious circumstances. In S. Kumra, R. Simpson, & R.J. Burke (Eds.), Oxford handbook of gender in organizations (pp. 314-331). New York: Oxford University Press.

Bryant, K. & Sheldon, P. (2017). Cyber dating in the age of mobile apps: Understanding motives, attitudes, and characteristics of users. American Communication Journal, 19(2), 1-15.

Bumpass, L. L. (1990). What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography, 27(4), 483–498.

Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 141-154.

Cain, S. (2012). Quiet. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Boldry, J., & Kashy, D. A. (2005). Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 510-532.

Carlson, N. R. (2011). Foundations of behavioral neuroscience (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning.

Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (2011). Understanding current causes of women’s under-representation in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 108(8), 3157-3162. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014871108

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014). Reported STDs in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/std-trends-508.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015a). Births and natality. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015b). Obesity and overweight. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Adult obesity causes and consequences. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html

Channick, R. (2019, July 9). Putting gender pay gap onto a broader stage. The Chicago Tribune, pp. 1-2.

Chappell, K. D., & Davis, K. E. (1998). Attachment, partner choice, and perception of romantic partners: An experimental test of the attachment-security hypothesis. Personal Relationships, 5, 327–342.

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1987). Origins and evolution of behavior disorders. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: Age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age. Journal or Personality, 81 (2), 171-183 DOI: 10.1111/j. 1467-6494.2012.00793

Cicirelli, V. (2009). Sibling relationships, later life. In D. Carr (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the life course and human development. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Clark, L. A., Kochanska, G., & Ready, R. (2000). Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 274–285.

Clark, L. A. & Watson, D. (1999). Temperament: A new paradigm for trait theory. In L.A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality. NY: Guilford.

Clarke, L., & Nichols, J. (1972). I have more fun with you than anybody. New York, NY: St. Martin’s.

Cohen, P. (2013). Marriage is declining globally. Can you say that? Retrieved from https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2013/06/12/marriage-is-declining/

Cohen-Bendehan, C. C., van de Beek, C. & Berenbaum, S. A. (2005). Prenatal sex hormone effects on child and adult sex-typed behavior: Methods and findings. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 230-237.

Cohn, D. (2013). In Canada, most babies now born to women 30 and older. Pew Research Center.

Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 361–373.

Copen, C.E., Daniels, K., & Mosher, W.D. (2013) First premarital cohabitation in the United States: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National health statistics reports; no 64. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Council of Economic Advisors. (2015). Gender pay gap: Recent trends and explanations. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/equal_pay_issue_brief_final.pdf

Crowley, K., Callanan, M. A., Tenenbaum, H. R., & Allen, E. (2001). Parents explain more often to boys than to girls during shared scientific thinking. Psychological Science, 12, 258–261.

Davidson, R. J. & Begley, S. (2012). The emotional life of your brain. New York: Penguin.

Davis, J. L., & Rusbult, C. E. (2001). Attitude alignment in close relationships. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 81(1), 65–84.

Demick, J. (1999). Parental development: Problem, theory, method, and practice. In R. L. Mosher, D. J. Youngman, & J. M. Day (Eds.), Human development across the life span: Educational and psychological applications (pp. 177–199). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Desai, S., & Andrist, L. (2010). Gender scripts and age at marriage in India. Demography, 47, 667-687. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0118 Desilver, D. (2016) Millions of young people in the US and EU are neither working nor learning. Pew Research Center (January 28, 2016). http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/01/28/us-eu-neet-population/

Diamond, M. (2002). Sex and gender are different: Sexual identity and gender identity are different. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(3), 320-334.

Douglass, C. B. (2007). From duty to desire: Emerging adulthood in Europe and its consequences. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 101–108.

Driver, J., & Gottman, J. (2004). Daily marital interactions and positive affect during marital conflict among newlywed couples. Family Process, 43, 301–314.

Dunn, J. (1984). Sibling studies and the developmental impact of critical incidents. In P.B. Baltes & O.G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol 6). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Dunn, J. (2007). Siblings and socialization. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization. New York: Guilford.

Dye, J. L. (2010). Fertility of American women: 2008. Current Population Reports. Retrieved from www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p20-563.pdf.

Ebrahimi, L., Amiri, M., Mohamadlou, M., & Rezapur, R. (2017). Attachment stules, parenting styles, and depression. International Journal of Mental Health, 15, 1064-1068.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Guthrie, I.K., Murphy, B.C., & Reiser, M. (1999). Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development, 70, 513-534.

Eisenberg, N., Hofer, C., Spinrad, T., Gershoff, E., Valiente, C., Losoya, S. L., Zhou, Q., Cumberland, A., Liew, J., Reiser, M., & Maxon, E. (2008). Understanding parent-adolescent conflict discussions: Concurrent and across-time prediction from youths’ dispositions and parenting. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73, (Serial No. 290, No. 2), 1-160.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton. Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Finkel, E. J., Burnette J. L., & Scissors L. E. (2007). Vengefully ever after: Destiny beliefs, state attachment anxiety, and forgiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 871–886.

Fraley, R. C. (2013). Attachment through the life course. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from nobaproject.com.

Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109 (2), 354-368.

Fraley, R. C., Roisman, G. I., Booth-LaForce, C., Owen, M. T., & Holland, A. S. (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 8817-838.

Frazier, P. A, Byer, A. L., Fischer, A. R., Wright, D. M., & DeBord, K. A. (1996). Adult attachment style and partner choice: Correlational and experimental findings. Personal Relationships, 3, 117–136.

Freitas, A. L., Azizian, A., Travers, S., & Berry, S. A. (2005). The evaluative connotation of processing fluency: Inherently positive or moderated by motivational context? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(6), 636–644.

Frieden, T. (2011, January 14). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report for the Centers for Disease Control (United States, Center for Disease Control). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6001al.htm?s_su6001al_w

Friedman, H. S., Tucker, J. S., Tomlinson-Keasey, C., Schwartz, J. E., Wingard, D. L., & Criqui, M. H. (1993). Does childhood personality predict longevity? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 176–185. doi:10.1037/0022- 3514.65.1.176

Fry, R. (2016). For the first time in the modern era, living with parents edges out other living arrangements for 18- to 34- year-olds. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center.

Fry, R. (2018). Millennials are the largest generation in the U. S. labor force. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact- tank/2018/04/11/millennials-largest-generation-us-labor-force/

Fryar, C. D., Carroll, M. D., & Ogden, C. L. (2014). Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, 1960-1962 through 2011-2012. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_11_12/obesity_adult_11_12.htm

Gallup Poll Report (2016). What millennials want from work and life. Business Journal. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/businessjournal/191435/millennials-work-life.aspx

Garcia, J. R., & Reiber, C. (2008). Hook-up behavior: A biopsychosocial perspective. The Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 2, 192–208.

Garcia, J. R., Reiber, C., Massey, S. G., & Merriwether, A. M. (2012). Sexual hookup culture: A review. Review of General Psychology, 16(2), 161-176. doi:10.1037/a0027911

Gates, G. J. (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender? Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/census-lgbt-demographics-studies/how-many-people-are-lesbian-gay- bisexual-and-transgender/

Gonzales, N. A., Coxe, S., Roosa, M. W., White, R. M. B., Knight, G. P., Zeiders, K. H., & Saenz, D. (2011). Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican-American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1

Gottman, J. M. (1999). Couple’s handbook: Marriage Survival Kit Couple’s Workshop. Seattle, WA: Gottman Institute.

Gottman, J. M., Carrere, S., Buehlman, K. T., Coan, J. A., & Ruckstuhl, L. (2000). Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(1), 42-58.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 221–233.

Grello, C. M., Welsh, D. P., Harper, M. S., & Dickson, J. W. (2003). Dating and sexual relationship trajectories and adolescent functioning. Adolescent & Family Health, 3, 103–112.

Grusec, J. E., Goodnow, J. J., & Cohen, L. (1996). Household work and the development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 32, 999–1007.