Chapter 21: Psychosocial Development in Adolescence

Chapter 21 Learning Objectives

- Describe the changes in self-concept and self-esteem in adolescence

- Summarize Erikson’s fifth psychosocial task of identity versus role confusion

- Describe Marcia’s four identity statuses

- Summarize the three stages of ethnic identity development

- Describe the parent-teen relationship

- Describe the role of peers

- Describe dating relationships

Self-concept and Self-esteem in Adolescence

In adolescence, teens continue to develop their self-concept. Their ability to think of the possibilities and to reason more abstractly may explain the further differentiation of the self during adolescence. However, the teen’s understanding of self is often full of contradictions. Young teens may see themselves as outgoing but also withdrawn, happy yet often moody, and both smart and completely clueless (Harter, 2012). These contradictions, along with the teen’s growing recognition that their personality and behavior seem to change depending on who they are with or where they are, can lead the young teen to feel like a fraud. With their parents they may seem angrier and sullen, with their friends they are more outgoing and goofier, and at work they are quiet and cautious. “Which one is really me?” may be the refrain of the young teenager. Harter (2012) found that adolescents emphasize traits such as being friendly and considerate more than do children, highlighting their increasing concern about how others may see them. Harter also found that older teens add values and moral standards to their self-descriptions.

As self-concept differentiates, so too does self-esteem. In addition to the academic, social, appearance, and physical/athletic dimensions of self-esteem in middle and late childhood, teens also add perceptions of their competency in romantic relationships, on the job, and in close friendships (Harter, 2006). Self-esteem often drops when children transition from one school setting to another, such as shifting from elementary to middle school, or junior high to high school (Ryan, Shim, & Makara, 2013). These drops are usually temporary, unless there are additional stressors such as parental conflict, or other family disruptions (De Wit, Karioja, Rye, & Shain, 2011). Self-esteem rises from mid to late adolescence for most teenagers, especially if they feel competent in their peer relationships, their appearance, and athletic abilities (Birkeland, Melkivik, Holsen, & Wold, 2012).

Erikson: Identity vs. Role Confusion

Erikson believed that the primary psychosocial task of adolescence was establishing an identity. Teens struggle with the question “Who am I?” This includes questions regarding their appearance, vocational choices and career aspirations, education, relationships, sexuality, political and social views, personality, and interests. Erikson saw this as a period of confusion and experimentation regarding identity and one’s life path. During adolescence we experience psychological moratorium, where teens put on hold commitment to an identity while exploring the options. The culmination of this exploration is a more coherent view of oneself. Those who are unsuccessful at resolving this stage may either withdraw further into social isolation or become lost in the crowd. However, more recent research, suggests that few leave this age period with identity achievement, and that most identity formation occurs during young adulthood (Côtè, 2006).

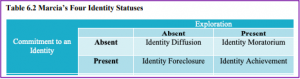

Expanding on Erikson’s theory, James Marcia (2010) identified four identity statuses that represent the four possible combinations of the dimension of commitment and exploration (see Table 6.2).

Table 6.2

The least mature status, and one common in many children, is identity diffusion. Identity diffusion is a status that characterizes those who have neither explored the options, nor made a commitment to an identity. Those who persist in this identity may drift aimlessly with little connection to those around them or have little sense of purpose in life.

Those in identity foreclosure have made a commitment to an identity without having explored the options. Some parents may make these decisions for their children and do not grant the teen the opportunity to make choices. In other instances, teens may strongly identify with parents and others in their life and wish to follow in their footsteps.

Identity moratorium is a status that describes those who are activity exploring in an attempt to establish an identity but have yet to have made any commitment. This can be an anxious and emotionally tense time period as the adolescent experiments with different roles and explores various beliefs. Nothing is certain and there are many questions, but few answers.

Identity achievement refers to those who after exploration have made a commitment. This is a long process and is not often achieved by the end of adolescence.

During high school and the college years, teens and young adults move from identity diffusion and foreclosure toward moratorium and achievement. The biggest gains in the development of identity are in college, as college students are exposed to a greater variety of career choices, lifestyles, and beliefs. This is likely to spur on questions regarding identity. A great deal of the identity work we do in adolescence and young adulthood is about values and goals, as we strive to articulate a personal vision or dream for what we hope to accomplish in the future (McAdams, 2013).

Developmental psychologists have researched several different areas of identity development and some of the main areas include:

Religious identity: The religious views of teens are often similar to that of their families (KimSpoon, Longo, & McCullough, 2012). Most teens may question specific customs, practices, or ideas in the faith of their parents, but few completely reject the religion of their families.

Political identity: The political ideology of teens is also influenced by their parents’ political beliefs. A new trend in the 21st century is a decrease in party affiliation among adults. Many adults do not align themselves with either the democratic or republican party but view themselves as more of an “independent”. Their teenage children are often following suit or become more apolitical (Côtè, 2006).

Vocational identity: While adolescents in earlier generations envisioned themselves as working in a particular job, and often worked as an apprentice or part-time in such occupations as teenagers, this is rarely the case today. Vocational identity takes longer to develop, as most of today’s occupations require specific skills and knowledge that will require additional education or are acquired on the job itself. In addition, many of the jobs held by teens are not in occupations that most teens will seek as adults.

Gender identity: Acquiring a gender identity is becoming an increasingly prolonged task as attitudes and norms regarding gender keep changing. The roles appropriate for males and females are evolving, and the lack of a gender binary allow adolescents more freedom to explore various aspects of gender. Some teens may foreclose on a gender identity as a way of dealing with this uncertainty, and they may adopt more stereotypic male or female roles (Sinclair & Carlsson, 2013).

Sexual identity: According to Carroll (2016), by age 14 most adolescents become interested in intimate relationships, and they may begin sexual experimentation. Many adolescent feel pressure to express interest in opposite-sex relationships, even if they are not ready to do so. This pressure can be especially stressful for those adolescents who are gay, lesbian, bisexual or questioning their sexual identity. Many non-heterosexual adolescents struggle with negative peer and family reactions during their exploration. A lack of parental acceptance, especially, can adversely affect the gay, lesbian or bisexual adolescent’s emerging sexual identity and can result in feelings of depression. In contrast, adolescents whose familes support their sexual identity have better health outcomes.

Ethnic identity refers to how people come to terms with who they are based on their ethnic or racial ancestry. “The task of ethnic identity formation involves sorting out and resolving positive and negative feelings and attitudes about one’s own ethnic group and about other groups and identifying one’s place in relation to both” (Phinney, 2006, p. 119). When groups differ in status in a culture, those from the non-dominant group have to be cognizant of the customs and values of those from the dominant culture. The reverse is rarely the case. This makes ethnic identity far less salient for members of the dominant culture. In the United States, those of European ancestry engage in less exploration of ethnic identity, than do those of non-European ancestry (Phinney, 1989). However, according to the U.S. Census (2012) more than 40% of Americans under the age of 18 are from ethnic minorities. For many ethnic minority teens, discovering one’s ethnic identity is an important part of identity formation.

Phinney’s model of ethnic identity formation is based on Erikson’s and Marcia’s model of identity formation (Phinney, 1990; Syed & Juang, 2014). Through the process of exploration and commitment, individual’s come to understand and create an ethic identity. Phinney suggests three stages or statuses with regard to ethnic identity:

- Unexamined Ethnic Identity: Adolescents and adults who have not been exposed to ethnic identity issues may be in the first stage, unexamined ethnic identity. This is often characterized with a preference for the dominant culture, or where the individual has given little thought to the question of their ethnic heritage. This is similar to diffusion in Marcia’s model of identity. Included in this group are also those who have adopted the ethnicity of their parents and other family members with little thought about the issues themselves, similar to Marcia’s foreclosure status (Phinney, 1990).

- Ethnic Identity Search: Adolescents and adults who are exploring the customs, culture, and history of their ethnic group are in the ethnic identity search stage, similar to Marcia’s moratorium status (Phinney, 1990). Often some event “awakens” a teen or adult to their ethnic group; either a personal experience with prejudice, a highly profiled case in the media, or even a more positive event that recognizes the contribution of someone from the individual’s ethnic group. Teens and adults in this stage will immerse themselves in their ethnic culture. For some, “it may lead to a rejection of the values of the dominant culture” (Phinney, 1990, p. 503).

- Achieved Ethnic Identity: Those who have actively explored their culture are likely to have a deeper appreciation and understanding of their ethnic heritage, leading to progress toward an achieved ethnic identity (Phinney, 1990). An achieved ethnic identity does not necessarily imply that the individual is highly involved in the customs and values of their ethnic culture. One can be confident in their ethnic identity without wanting to maintain the language or other customs.

The development of ethnic identity takes time, with about 25% of tenth graders from ethnic minority backgrounds having explored and resolved the issues (Phinney, 1989). The more ethnically homogeneous the high school, the less identity exploration and achievement (UmanaTaylor, 2003). Moreover, even in more ethnically diverse high schools, teens tend to spend more time with their own group, reducing exposure to other ethnicities. This may explain why, for many, college becomes the time of ethnic identity exploration. “[The] transition to college may serve as a consciousness-raising experience that triggers exploration” (Syed & Azmitia, 2009, p. 618).

It is also important to note that those who do achieve ethnic identity may periodically reexamine the issues of ethnicity. This cycling between exploration and achievement is common not only for ethnic identity formation, but in other aspects of identity development (Grotevant, 1987) and is referred to as MAMA cycling or moving back and forth between moratorium and achievement.

Bicultural/Multiracial Identity: Ethnic minorities must wrestle with the question of how, and to what extent, they will identify with the culture of the surrounding society and with the culture of their family. Phinney (2006) suggests that people may handle it in different ways. Some may keep the identities separate, others may combine them in some way, while others may reject some of them. Bicultural identity means the individual sees himself or herself as part of both the ethnic minority group and the larger society. Those who are multiracial, that is whose parents come from two or more ethnic or racial groups, have a more challenging task. In some cases, their appearance may be ambiguous. This can lead to others constantly asking them to categorize themselves. Phinney (2006) notes that the process of identity formation may start earlier and take longer to accomplish in those who are not mono-racial.

Negative Identity: A negative identity is the adoption of norms and values that are the opposite of one’s family and culture, and it is assumed to be one of the more problematic outcomes of identity development in young people (Hihara, Umemura, & Sigimura, 2019). Those with a negative identity hold dichotomous beliefs, and consequently divide the world into two categories (e.g., friend or foe, good or bad). Hihara et al. suggest that this may be because teens with a negative identity cannot integrate information and beliefs that exist in both their inner and outer worlds. In addition, those with a negative identity are generally hostile and cynical toward society, often because they do not trust the world around them. These beliefs may lead teens to engage in delinquent and criminal behavior and prevent them from engaging in more positive acts that could be beneficial to society.

Parents and Teens: Autonomy and Attachment

While most adolescents get along with their parents, they do spend less time with them (Smetana, 2011). This decrease in the time spent with families may be a reflection of a teenager’s greater desire for independence or autonomy. It can be difficult for many parents to deal with this desire for autonomy. However, it is likely adaptive for teenagers to increasingly distance themselves and establish relationships outside of their families in preparation for adulthood. This means that both parents and teenagers need to strike a balance between autonomy, while still maintaining close and supportive familial relationships.

Children in middle and late childhood are increasingly granted greater freedom regarding moment-to-moment decision making. This continues in adolescence, as teens are demanding greater control in decisions that affect their daily lives. This can increase conflict between parents and their teenagers. For many adolescents, this conflict centers on chores, homework, curfew, dating, and personal appearance. These are all things many teens believe they should manage that parents previously had considerable control over. Teens report more conflict with their mothers, as many mothers believe they should still have some control over many of these areas, yet often report their mothers to be more encouraging and supportive (Costigan, Cauce, & Etchison, 2007). As teens grow older, more compromise is reached between parents and teenagers (Smetana, 2011). Parents are more controlling of daughters, especially early maturing girls, than they are sons (Caspi, Lynam, Moffitt, & Silva, 1993). In addition, culture and ethnicity also play a role in how restrictive parents are with the daily lives of their children (Chen, Vansteenkiste, Beyers, Soensens, & Van Petegem, 2013).

Having supportive, less conflict ridden relationships with parents also benefits teenagers. Research on attachment in adolescence find that teens who are still securely attached to their parents have less emotional problems (Rawatlal, Kliewer & Pillay, 2015), are less likely to engage in drug abuse and other criminal behaviors (Meeus, Branje & Overbeek, 2004), and have more positive peer relationships (Shomaker & Furman, 2009).

Peers

As children become adolescents, they usually begin spending more time with their peers and less time with their families, and these peer interactions are increasingly unsupervised by adults. Children’s notions of friendship often focus on shared activities, whereas adolescents’ notions of friendship increasingly focus on intimate exchanges of thoughts and feelings. During adolescence, peer groups evolve from primarily single-sex to mixed-sex. Adolescents within a peer group tend to be similar to one another in behavior and attitudes, which has been explained as a function of homophily, that is, adolescents who are similar to one another choose to spend time together in a “birds of a feather flock together” way. Adolescents who spend time together also shape each other’s behavior and attitudes.

Peers can serve both positive and negative functions during adolescence. Negative peer pressure can lead adolescents to make riskier decisions or engage in more problematic behavior than they would alone or in the presence of their family. For example, adolescents are much more likely to drink alcohol, use drugs, and commit crimes when they are with their friends than when they are alone or with their family. One of the most widely studied aspects of adolescent peer influence is known as deviant peer contagion (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011), which is the process by which peers reinforce problem behavior by laughing or showing other signs of approval that then increase the likelihood of future problem behavior.

However, peers also serve as an important source of social support and companionship during adolescence, and adolescents with positive peer relationships are happier and better adjusted than those who are socially isolated or have conflictual peer relationships.

Crowds are an emerging level of peer relationships in adolescence. In contrast to friendships, which are reciprocal dyadic relationships, and cliques, which refer to groups of individuals who interact frequently, crowds are characterized more by shared reputations or images than actual interactions (Brown & Larson, 2009). These crowds reflect different prototypic identities, such as jocks or brains, and are often linked with adolescents’ social status and peers’ perceptions of their values or behaviors.

Romantic Relationships

Adolescence is the developmental period during which romantic relationships typically first emerge. By the end of adolescence, most American teens have had at least one romantic relationship (Dolgin, 2011). However, culture does play a role as Asian Americans and Latinas are less likely to date than other ethnic groups (Connolly, Craig, Goldberg, & Pepler, 2004). Dating serves many purposes for teens, including having fun, companionship, status, socialization, sexual experimentation, intimacy, and partner selection for those in late adolescence (Dolgin, 2011).

There are several stages in the dating process beginning with engaging in mixed-sex group activities in early adolescence (Dolgin, 2011). The same-sex peer groups that were common during childhood expand into mixed-sex peer groups that are more characteristic of adolescence. Romantic relationships often form in the context of these mixed-sex peer groups (Connolly, Furman, & Konarski, 2000). Interacting in mixed-sex groups is easier for teens as they are among a supportive group of friends, can observe others interacting, and are kept safe from a too early intimate relationship. By middle adolescence, teens are engaging in brief, casual dating or in group dating with established couples (Dolgin, 2011). Then in late adolescence dating involves exclusive, intense relationships. These relationships tend to be long-lasting and continue for a year or longer, however, they may also interfere with friendships.

Although romantic relationships during adolescence are often short-lived rather than long-term committed partnerships, their importance should not be minimized. Adolescents spend a great deal of time focused on romantic relationships, and their positive and negative emotions are more tied to romantic relationships, or lack thereof than to friendships, family relationships, or school (Furman & Shaffer, 2003). Romantic relationships contribute to adolescents’ identity formation, changes in family and peer relationships, and emotional and behavioral adjustment.

Furthermore, romantic relationships are centrally connected to adolescents’ emerging sexuality. Parents, policymakers, and researchers have devoted a great deal of attention to adolescents’ sexuality, in large part because of concerns related to sexual intercourse, contraception, and preventing teen pregnancies. However, sexuality involves more than this narrow focus. For example, adolescence is often when individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender come to perceive themselves as such (Russell, Clarke, & Clary, 2009). Thus, romantic relationships are a domain in which adolescents experiment with new behaviors and identities.

However, a negative dating relationship can adversely affect an adolescent’s development. Soller (2014) explored the link between relationship inauthenticity and mental health. Relationship inauthenticity refers to an incongruence between thoughts/feelings and actions within a relationship. Desires to gain partner approval and demands in the relationship may negatively affect an adolescent’s sense of authenticity. Soller found that relationship inauthenticity was positively correlated with poor mental health, including depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts, especially for females.

References

Albert, D., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Adolescent judgment and decision making. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 211– 224.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Fifth Edition). Washington, D. C.: Author.

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724-731.

Birkeland, M. S., Melkivik, O., Holsen, I., & Wold, B. (2012). Trajectories of global self-esteem during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 43-54.

Bosson, J. K., Vandello, J., & Buckner, C. (2019). The psychology of sex and gender. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brass, N., McKellar, North, E., & Ryan, A. (2019). Early adolescents’ adjustment at school: A fresh look at grade and gender differences. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(5), 689-716.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley.

Carney, C., McGehee, D., Harland, K., Weiss, M., & Raby, M. (2015, March). Using naturalistic driving data to assess the prevalence of environmental factors and driver behaviors in teen driver crashes. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. Retrieved from https://www.aaafoundation.org/sites/default/files/2015TeenCrashCausationReport.pdf

Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Caspi, A., Lynam, D., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1993). Unraveling girls’ delinquency: Biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 19-30.

Center for Disease Control. (2004). Trends in the prevalence of sexual behaviors, 1991-2003. Bethesda, MD: Author.

Center for Disease Control. (2016). Birth rates (live births) per 1,000 females aged 15–19 years, by race and Hispanic ethnicity, select years. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/birth-rates-chart-2000-2011-text.htm

Centers for Disease Control. (2018a). Teen drivers: Get the facts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/motorvehiclesafety/teen_drivers/teendrivers_factsheet.html

Centers for Disease Control. (2018b). Trends in the behaviors that contribute to unintentional injury: National Youth Risk Behavioral Survey. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/2017_unintentional_injury_trend_yrbs.pdf

Chein, J., Albert, D., O’Brien, L., Uckert, K., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Developmental Science, 14(2), F1-F10. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Soensens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2013). Autonomy in family decision making for Chinese adolescents: Disentangling the dual meaning of autonomy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 1184- 1209.

Connolly, J., Craig, W., Goldberg, A., & Pepler, D. (2004). Mixed-gender groups, dating, and romantic relationships in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14, 185-207.

Connolly, J., Furman, W., & Konarski, R. (2000). The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development, 71, 1395–1408.

Costigan, C. L., Cauce, A. M., & Etchinson, K. (2007). Changes in African American mother-daughter relationships during adolescence: Conflict, autonomy, and warmth. In B. J. R. Leadbeater & N. Way (Eds.), Urban girls revisited: Building strengths (pp. 177-201). New York NY: New York University Press.

Côtè, J. E. (2006). Emerging adulthood as an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In J. J. Arnett & J. T. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century, (pp. 85-116). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association Press.

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

Crooks, K. L., & Baur, K. (2007). Our sexuality (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Crosnoe, R., & Benner, A. D. (2015). Children at school. In M. H. Bornstein, T. Leventhal, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Ecological settings and processes (pp. 268-304). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

De Wit, D. J., Karioja, K., Rye, B. J., & Shain, M. (2011). Perceptions of declining classmate and teacher support following the transition to high school: Potential correlates of increasing student mental health difficulties. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 556-572.

Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214.

Dobbs, D. (2012). Beautiful brains. National Geographic, 220(4), 36. Dolgin, K. G. (2011). The adolescent: Development, relationships, and culture (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Duchesne, S., Larose, S., & Feng, B. (2019). Achievement goals and engagement with academic work in early high school: Does seeking help from teachers matter? Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(2), 222-252.

Dudovitz, R.N., Chung, P.J., Elliott, M.N., Davies, S.L., Tortolero, S,… Baumler, E. (2015). Relationship of age for grade and pubertal stage to early initiation of substance use. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12, 150234. doi:10.5888/pcd12.150234.

Eccles, J. S., & Rosner, R. W. (2015). School and community influences on human development. In M. H. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science (7th ed.). NY: Psychology Press.

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38, 1025-1034.

Euling, S. Y., Herman-Giddens, M.E., Lee, P.A., Selevan, S. G., Juul, A., Sorensen, T. I., Dunkel, L., Himes, J.H., Teilmann, G., & Swan, S.H. (2008). Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics, 121, S172-91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813D.

Eveleth, P. & Tanner, J. (1990). Worldwide variation in human growth (2nd edition). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Furman, W., & Shaffer, L. (2003). The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 3–22). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Garcia, A. R., Metraux, S., Chen, C., Park, J., Culhane, D., & Furstenberg, F. (2018). Patterns of multisystem service use and school dropout among seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-grade students. Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(8), 1041-1073.

Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37. Goodman, G. (2006). Acne and acne scarring: The case for active and early intervention. Australia Family Physicians, 35, 503- 504.

Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262-289.

Grotevant, H. (1987). Toward a process model of identity formation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 2, 203-222

Harter, S. (2006). The self. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3 Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 505-570). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Harter, S. (2012). Emerging self-processes during childhood and adolescence. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney, (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 680-715). New York: Guilford.

Hihara, S., Umemura, T., & Sigimura, K. (2019). Considering the negatively formed identity: Relationships between negative identity and problematic psychosocial beliefs. Journal of Adolescence, 70, 24-32.

Hudson, J. I., Hiripi, E., Pope, H. G., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348-358.

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. (2017). Fatality facts: Teenagers 2016. Retrieved from http://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/teenagers/fatalityfacts/teenagersExternal

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kim-Spoon, J., Longo, G.S., & McCullough, M.E. (2012). Parent-adolescent relationship quality as moderator for the influences of parents’ religiousness on adolescents’ religiousness and adjustment. Journal or Youth & Adolescence, 41 (12), 1576-1578.

King’s College London. (2019). Genetic study revelas metabolic origins of anorexia. Retrieved from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/07/190715164655.htm

Klaczynski, P. (2001). Analytic and heuristic processing influences on adolescent reasoning and decision-making. Child Development, 72 (3), 844-861.

Klauer, S. G., Gun, F., Simons-Morton, B. G., Ouimet, M. C., Lee, S. E., & Dingus, T. A. (2014). Distracted driving a risk of road crashes among novice and experienced drivers. New England Journal of Medicine, 370, 54-59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204142

Kuhn, D. (2013). Reasoning. In. P.D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. (Vol. 1, pp. 744-764). New York NY: Oxford University Press.

Lee, J. C., & Staff, J. (2007). When work matters: The varying impact of work intensity on high school dropout. Sociology of Education, 80(2), 158–178.

Longest, K. C., & Shanahan, M. J. (2007). Adolescent work intensity and substance use: The mediational and moderational roles of parenting. Journal of Family and Marriage, 69(3), 703-720.

Luciano, M., & Collins, P. F. (2012). Incentive motivation, cognitive control, and the adolescent brain: Is it time for a paradigm shift. Child Development Perspectives, 6 (4), 394-399.

March of Dimes. (2012). Teenage pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/teenage-pregnancy.pdf

Marcia, J. (2010). Life transitions and stress in the context of psychosocial development. In T.W. Miller (Ed.), Handbook of stressful transitions across the lifespan (Part 1, pp. 19-34). New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media.

Marsh, H. W., & Kleitman, S. (2005). Consequences of employment during high school: Character building, subversion of academic goals, or a threshold? American Educational Research Journal, 42, 331–369.

McAdams, D. P. (2013). Self and Identity. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from: nobaproject.com.

McClintock, M. & Herdt, G. (1996). Rethinking puberty: The development of sexual attraction. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 5, 178-183.

Meeus, W., Branje, S., & Overbeek, G. J. (2004). Parents and partners in crime: A six-year longitudinal study on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 45(7), 1288-1298. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46,1341–1353. doi:10.1037/a0020205

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2012). Peer relationships and depressive symptomatology in boys at puberty. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 429–435. doi: 10.1037/a0026425

Miller, B. C., Benson, B., & Galbraith, K. A. (2001). Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review, 21(1), 1-38. doi:10.1006/drev.2000.0513

National Center for Health Statistics. (2014). Leading causes of death. Retrieved from: http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10_us.html

National Center for Statistics and Analysis. (2016, May). Young drivers: 2014 data. (Traffic Safety Facts. Report No. DOT HS 812 278). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Retrieved from: http://wwwnrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/812278.pdf

National Eating Disorders Association. (2016). Health consequences of eating disorders. Retrieved from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/health-consequences-eating-disorders

National Institutes of Mental Health. (2016). Eating disorders. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml

National Sleep Foundation. (2016). Teens and sleep. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep topics/teens-and-sleep

Nelson, A., & Spears Brown, C. (2019). Too pretty for homework: Sexualized gender stereotypes predict academic attitudes for gener-typical early adolescent girls. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(4), 603-617.

Office of Adolescent Health. (2018). A day in the life. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/facts-and-stats/day-in-thelife/index.html

Pew Research Center. (2015). College-educated men taking their time becoming dads. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/06/19/college-educated-men-take-their-time-becoming-dads/

Phinney, J. S. (1989). Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 34- 49.

Phinney, J. S. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 499-514. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499

Phinney, J. S. (2006). Ethnic identity exploration. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.) Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st Century. (pp. 117-134) Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Rawatlal, N., Kliewer, W., & Pillay, B. J. (2015). Adolescent attachment, family functioning and depressive symptoms. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 21(3), 80-85. doi:10.7196/SAJP.8252

Rosenbaum, J. (2006). Reborn a virgin: Adolescents’ retracting of virginity pledges and sexual histories. American Journal of Public Health, 96(6), 1098-1103.

Ryan, A. M., Shim, S. S., & Makara, K. A. (2013). Changes in academic adjustment and relational self-worth across the transition to middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1372-1384.

Russell, S. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are teens “post-gay”? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 884–890.

Sadker, M. (2004). Gender equity in the classroom: The unfinished agenda. In M. Kimmel (Ed.), The gendered society reader, 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schwartz, P. D., Maynard, A. M., & Uzelac, S. M. (2008). Adolescent egocentrism: A contemporary view. Adolescence, 43, 441- 447.

Seifert, K. (2012). Educational psychology. Retrieved from http://cnx.org/content/col11302/1.2

Shin, H., & Ryan, A. M. (2014). Early adolescent friendships and academic adjustment: Examining selection and influence processes with longitudinal social network analysis. Developmental Psychology, 50(11), 2462-2472.

Shomaker, L. B., & Furman, W. (2009). Parent-adolescent relationship qualities, internal working models, and attachment styles as predictors of adolescents’ interactions with friends. Journal or Social and Personal Relationships, 2, 579-603.

Sinclair, S., & Carlsson, R. (2013). What will I be when I grow up? The impact of gender identity threat on adolescents’ occupational preferences. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 465-474.

Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. Soller, B. (2014). Caught in a bad romance: Adolescent romantic relationships and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), 56-72.

Staff, J., Schulenberg, J. E., & Bachman, J. G. (2010). Adolescent work intensity, school performance, and academic engagement. Sociology of Education, 83, p. 183–200.

Staff, J., Van Eseltine, M., Woolnough, A., Silver, E., & Burrington, L. (2011). Adolescent work experiences and family formation behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 150-164. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00755.x

Steinberg, L., Icenogle, G., Shulman, E.P., et al. (2018). Around the world, adolescence is a time of heightened sensation seeking and immature self-regulation. Developmental Science, 21, e12532. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12532

Syed, M., & Azmitia, M. (2009). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity during the college years. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19, 601-624. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00609.x

Syed, M., & Juang, L. P. (2014). Ethnic identity, identity coherence, and psychological functioning: Testing basic assumptions of the developmental model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(2), 176-190. doi:10.1037/a0035330

Tartamella, L., Herscher, E., Woolston, C. (2004). Generation extra large: Rescuing our children from the obesity epidemic. New York: Basic Books.

Taylor, J. & Gilligan, C., & Sullivan, A. (1995). Between voice and silence: Women and girls, race and relationship. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Thomas, R. M. (1979). Comparing theories of child development. Santa Barbara, CA: Wadsworth.

Troxel, W. M., Rodriquez, A., Seelam, R., Tucker, J. Shih, R., & D’Amico. (2019). Associations of longitudinal sleep trajectories with risky sexual behavior during late adolescence. Health Psychology. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fhea0000753

Umana-Taylor, A. (2003). Ethnic identity and self-esteem. Examining the roles of social context. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 139-146.

United States Census. (2012). 2000-2010 Intercensal estimates. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/popest/data/index.html

United States Department of Education. (2018). Trends in high school dropout and completion rates in the United States: 2018. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019117.pdf

United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). Employment projections. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_chart_001.htm

United States Department of Labor, Office of Disability Employment Policy. (2019). School based prepatory experiences. Retrieved from: https://www.dol.gov/odep/categories/youth/school.htm

University of California at Los Angeles Medical Center. (2000). Acne. Retrieved from http://www.mednet.ucla.edu

Vaillancourt, M. C., Paiva, A. O., Véronneau, M., & Dishion, T. (2019). How do individual predispositions and family dynamics contribute to academic adjustment through the middle school years? The mediating role of friends’ characteristics. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(4), 576-602.

Wade, T. D., Keski‐Rahkonen, A., & Hudson, J. I. (2011). Epidemiology of eating disorders. Textbook of Psychiatric Epidemiology, Third Edition, 343-360.

Weintraub, K. (2016). Young and sleep deprived. Monitor on Psychology, 47(2), 46-50. Weir, K. (2015). Marijuana and the developing brain. Monitor on Psychology, 46(10), 49-52.

Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44.

Yau, J. C., & Reich, S. M. (2018). “It’s just a lot of work”: Adolescents’ self-presentation norms and practices on Facebook and Instagram. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(1), 196-209.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 6 from Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective Second Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 unported license.