Chapter 19: Physical Development in Adolescence

Chapter 19 Learning Objectives

- Summarize the overall physical growth

- Describe the changes that occur during puberty

- Describe the changes in brain maturation

- Describe the changes in sleep

- Describe gender intensification

- Identify nutritional concerns

- Describe eating disorders

- Explain the prevalence, risk factors, and consequences of adolescent pregnancy

Growth in Adolescence

Puberty is a period of rapid growth and sexual maturation. These changes begin sometime between eight and fourteen. Girls begin puberty at around ten years of age and boys begin approximately two years later. Pubertal changes take around three to four years to complete. Adolescents experience an overall physical growth spurt. The growth proceeds from the extremities toward the torso. This is referred to as distalproximal development. First the hands grow, then the arms, and finally the torso. The overall physical growth spurt results in 10-11 inches of added height and 50 to 75 pounds of increased weight. The head begins to grow sometime after the feet have gone through their period of growth. Growth of the head is preceded by growth of the ears, nose, and lips. The difference in these patterns of growth result in adolescents appearing awkward and out-of-proportion. As the torso grows, so does the internal organs. The heart and lungs experience dramatic growth during this period.

During childhood, boys and girls are quite similar in height and weight. However, gender differences become apparent during adolescence. From approximately age ten to fourteen, the average girl is taller, but not heavier, than the average boy. After that, the average boy becomes both taller and heavier, although individual differences are certainly noted. As adolescents physically mature, weight differences are more noteworthy than height differences. At eighteen years of age, those that are heaviest weigh almost twice as much as the lightest, but the tallest teens are only about 10% taller than the shortest (Seifert, 2012).

Both height and weight can certainly be sensitive issues for some teenagers. Most modern societies, and the teenagers in them, tend to favor relatively short women and tall men, as well as a somewhat thin body build, especially for girls and women. Yet, neither socially preferred height nor thinness is the destiny for many individuals. Being overweight, in particular, has become a common, serious problem in modern society due to the prevalence of diets high in fat and lifestyles low in activity (Tartamella, Herscher, & Woolston, 2004). The educational system has, unfortunately, contributed to the problem as well by gradually restricting the number of physical education courses and classes in the past two decades.

Average height and weight are also related somewhat to racial and ethnic background. In general, children of Asian background tend to be slightly shorter than children of European and North American background. The latter in turn tend to be shorter than children from African societies (Eveleth & Tanner, 1990). Body shape differs slightly as well, though the differences are not always visible until after puberty. Asian background youth tend to have arms and legs that are a bit short relative to their torsos, and African background youth tend to have relatively long arms and legs. The differences are only averages, as there are large individual differences as well.

Sexual Development

Typically, the growth spurt is followed by the development of sexual maturity. Sexual changes are divided into two categories: Primary sexual characteristics and secondary sexual characteristics. Primary sexual characteristics are changes in the reproductive organs. For males, this includes growth of the testes, penis, scrotum, and spermarche or first ejaculation of semen. This occurs between 11 and 15 years of age. For females, primary characteristics include growth of the uterus and menarche or the first menstrual period. The female gametes, which are stored in the ovaries, are present at birth, but are immature. Each ovary contains about 400,000 gametes, but only 500 will become mature eggs (Crooks & Baur, 2007). Beginning at puberty, one ovum ripens and is released about every 28 days during the menstrual cycle. Stress and higher percentage of body fat can bring menstruation at younger ages.

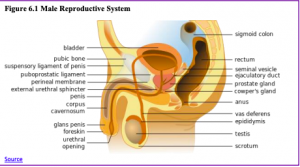

Male Anatomy: Males have both internal and external genitalia that are responsible for procreation and sexual intercourse. Males produce their sperm on a cycle, and unlike the female’s ovulation cycle, the male sperm production cycle is constantly producing millions of sperm daily. The main male sex organs are the penis and the testicles, the latter of which produce semen and sperm. The semen and sperm, as a result of sexual intercourse, can fertilize an ovum in the female’s body; the fertilized ovum (zygote) develops into a fetus which is later born as a child.

Figure 6.1

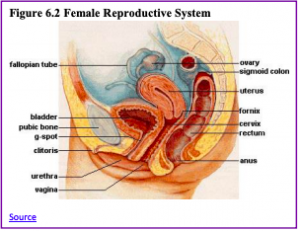

Figure 6.2

Female Anatomy: Female external genitalia is collectively known as the vulva, which includes the mons veneris, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vaginal opening, and urethral opening. Female internal reproductive organs consist of the vagina, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. The uterus hosts the developing fetus, produces vaginal and uterine secretions, and passes the male’s sperm through to the fallopian tubes while the ovaries release the eggs. A female is born with all her eggs already produced. The vagina is attached to the uterus through the cervix, while the uterus is attached to the ovaries via the fallopian tubes. Females have a monthly reproductive cycle; at certain intervals the ovaries release an egg, which passes through the fallopian tube into the uterus. If, in this transit, it meets with sperm, the sperm might penetrate and merge with the egg, fertilizing it. If not fertilized, the egg is flushed out of the system through menstruation.

Secondary sexual characteristics are visible physical changes not directly linked to reproduction but signal sexual maturity. For males this includes broader shoulders and a lower voice as the larynx grows. Hair becomes coarser and darker, and hair growth occurs in the pubic area, under the arms and on the face. For females, breast development occurs around age 10, although full development takes several years. Hips broaden, and pubic and underarm hair develops and also becomes darker and coarser.

Acne: An unpleasant consequence of the hormonal changes in puberty is acne, defined as pimples on the skin due to overactive sebaceous (oil-producing) glands (Dolgin, 2011). These glands develop at a greater speed than the skin ducts that discharges the oil. Consequently, the ducts can become blocked with dead skin and acne will develop. According to the University of California at Los Angeles Medical Center (2000), approximately 85% of adolescents develop acne, and boys develop acne more than girls because of greater levels of testosterone in their systems (Dolgin, 2011). Experiencing acne can lead the adolescent to withdraw socially, especially if they are self-conscious about their skin or teased (Goodman, 2006).

Effects of Pubertal Age: The age of puberty is getting younger for children throughout the world. According to Euling et al. (2008) data are sufficient to suggest a trend toward an earlier breast development onset and menarche in girls. A century ago the average age of a girl’s first period in the United States and Europe was 16, while today it is around 13. Because there is no clear marker of puberty for boys, it is harder to determine if boys are maturing earlier too. In addition to better nutrition, less positive reasons associated with early puberty for girls include increased stress, obesity, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

Cultural differences are noted with Asian-American girls, on average, developing last, while African American girls enter puberty the earliest. Hispanic girls start puberty the second earliest, while European-American girls rank third in their age of starting puberty. Although African American girls are typically the first to develop, they are less likely to experience negative consequences of early puberty when compared to European-American girls (Weir, 2016).

Research has demonstrated mental health problems linked to children who begin puberty earlier than their peers. For girls, early puberty is associated with depression, substance use, eating disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and early sexual behavior (Graber, 2013). Early maturing girls demonstrate more anxiety and less confidence in their relationships with family and friends, and they compare themselves more negatively to their peers (Weir, 2016).

Problems with early puberty seem to be due to the mismatch between the child’s appearance and the way she acts and thinks. Adults especially may assume the child is more capable than she actually is, and parents might grant more freedom than the child’s age would indicate. For girls, the emphasis on physical attractiveness and sexuality is emphasized at puberty and they may lack effective coping strategies to deal with the attention they may receive.

Additionally, mental health problems are more likely to occur when the child is among the first in his or her peer group to develop. Because the preadolescent time is one of not wanting to appear different, early developing children stand out among their peer group and gravitate toward those who are older. For girls, this results in them interacting with older peers who engage in risky behaviors such as substance use and early sexual behavior (Weir, 2016).

Boys also see changes in their emotional functioning at puberty. According to Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, and Graber (2010), while most boys experienced a decrease in depressive symptoms during puberty, boys who began puberty earlier and exhibited a rapid tempo, or a fast rate of change, actually increased in depressive symptoms. The effects of pubertal tempo were stronger than those of pubertal timing, suggesting that rapid pubertal change in boys may be a more important risk factor than the timing of development. In a further study to better analyze the reasons for this change, Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn and Graber (2012) found that both early maturing boys and rapidly maturing boys displayed decrements in the quality of their peer relationships as they moved into early adolescence, whereas boys with more typical timing and tempo development actually experienced improvements in peer relationships. The researchers concluded that the transition in peer relationships may be especially challenging for boys whose pubertal maturation differs significantly from those of others their age. Consequences for boys attaining early puberty were increased odds of cigarette, alcohol, or another drug use (Dudovitz, et al., 2015).

Gender Role Intensification: At about the same time that puberty accentuates gender, role differences also accentuate for at least some teenagers. Some girls who excelled at math or science in elementary school, may curb their enthusiasm and displays of success at these subjects for fear of limiting their popularity or attractiveness as girls (Taylor, Gilligan, & Sullivan, 1995; Sadker, 2004). Some boys who were not especially interested in sports previously may begin dedicating themselves to athletics to affirm their masculinity in the eyes of others. Some boys and girls who once worked together successfully on class projects may no longer feel comfortable doing so, or alternatively may now seek to be working partners, but for social rather than academic reasons. Such changes do not affect all youngsters equally, nor affect any one youngster equally on all occasions. An individual may act like a young adult on one day, but more like a child the next.

Adolescent Brain

The brain undergoes dramatic changes during adolescence. Although it does not get larger, it matures by becoming more interconnected and specialized (Giedd, 2015). The myelination and development of connections between neurons continue. This results in an increase in the white matter of the brain and allows the adolescent to make significant improvements in their thinking and processing skills. Different brain areas become myelinated at different times. For example, the brain’s language areas undergo myelination during the first 13 years. Completed insulation of the axons consolidates these language skills but makes it more difficult to learn a second language. With greater myelination, however, comes diminished plasticity as a myelin coating inhibits the growth of new connections (Dobbs, 2012).

Even as the connections between neurons are strengthened, synaptic pruning occurs more than during childhood as the brain adapts to changes in the environment. This synaptic pruning causes the gray matter of the brain, or the cortex, to become thinner but more efficient (Dobbs, 2012). The corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres, continues to thicken allowing for stronger connections between brain areas. Additionally, the hippocampus becomes more strongly connected to the frontal lobes, allowing for greater integration of memory and experiences into our decision making.

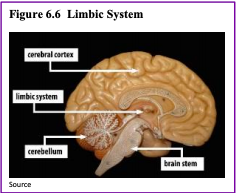

The limbic system, which regulates emotion and reward, is linked to the hormonal changes that occur at puberty. The limbic system is also related to novelty seeking and a shift toward interacting with peers. In contrast, the prefrontal cortex which is involved in the control of impulses, organization, planning, and making good decisions, does not fully develop until the mid-20s. According to Giedd (2015) the significant aspect of the later developing prefrontal cortex and early development of the limbic system is the “mismatch” in timing between the two. The approximately ten years that separates the development of these two brain areas can result in risky behavior, poor decision making, and weak emotional control for the adolescent. When puberty begins earlier, this mismatch extends even further.

Teens often take more risks than adults and according to research it is because they weigh risks and rewards differently than adults do (Dobbs, 2012). For adolescents the brain’s sensitivity to the neurotransmitter dopamine peaks, and dopamine is involved in reward circuits, so the possible rewards outweighs the risks. Adolescents respond especially strongly to social rewards during activities, and they prefer the company of others their same age. Chein et al. (2011) found that peers sensitize brain regions associated with potential rewards. For example, adolescent drivers make risky driving decisions when with friends to impress them, and teens are much more likely to commit crimes together in comparison to adults (30 and older) who commit them alone (Steinberg et al., 2017). In addition to dopamine, the adolescent brain is affected by oxytocin which facilitates bonding and makes social connections more rewarding. With both dopamine and oxytocin engaged, it is no wonder that adolescents seek peers and excitement in their lives that could end up actually harming them.

Because of all the changes that occur in the adolescent brain, the chances for abnormal development can occur, including mental illness. In fact, 50% of the mental illness occurs by the age 14 and 75% occurs by age 24 (Giedd, 2015). Additionally, during this period of development the adolescent brain is especially vulnerable to damage from drug exposure. For example, repeated exposure to marijuana can affect cellular activity in the endocannabinoid system. Consequently, adolescents are more sensitive to the effects of repeated marijuana exposure (Weir, 2015).

However, researchers have also focused on the highly adaptive qualities of the adolescent brain which allow the adolescent to move away from the family towards the outside world (Dobbs, 2012; Giedd, 2015). Novelty seeking and risk taking can generate positive outcomes including meeting new people and seeking out new situations. Separating from the family and moving into new relationships and different experiences are actually quite adaptive for society.

Adolescent Sleep

According to the National Sleep Foundation (NSF) (2016), adolescents need about 8 to 10 hours of sleep each night to function best. The most recent Sleep in America poll in 2006 indicated that adolescents between sixth and twelfth grade were not getting the recommended amount of sleep. On average adolescents only received 7 ½ hours of sleep per night on school nights with younger adolescents getting more than older ones (8.4 hours for sixth graders and only 6.9 hours for those in twelfth grade). For the older adolescents, only about one in ten (9%) get an optimal amount of sleep, and they are more likely to experience negative consequences the following day. These include feeling too tired or sleepy, being cranky or irritable, falling asleep in school, having a depressed mood, and drinking caffeinated beverages (NSF, 2016). Additionally, they are at risk for substance abuse, car crashes, poor academic performance, obesity, and a weakened immune system (Weintraub, 2016).

Troxel et al. (2019) found that insufficient sleep in adolescents is a predictor of risky sexual behaviors. Reasons given for this include that those adolescents who stay out late, typically without parental supervision, are more likely to engage in a variety of risky behaviors, including risky sex, such as not using birth control or using substances before/during sex. An alternative explanation for risky sexual behavior is that the lack of sleep negatively affects impulsivity and decision-making processes.

Why do adolescents not get adequate sleep? In addition to known environmental and social factors, including work, homework, media, technology, and socializing, the adolescent brain is also a factor. As adolescent go through puberty, their circadian rhythms change and push back their sleep time until later in the evening (Weintraub, 2016). This biological change not only keeps adolescents awake at night, it makes it difficult for them to wake up. When they are awake too early, their brains do not function optimally. Impairments are noted in attention, academic achievement, and behavior while increases in tardiness and absenteeism are also seen.

To support adolescents’ later sleeping schedule, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that school not begin any earlier than 8:30 a.m. Unfortunately, over 80% of American schools begin their day earlier than 8:30 a.m. with an average start time of 8:03 a.m. (Weintraub, 2016). Psychologists and other professionals have been advocating for later school times, and they have produced research demonstrating better student outcomes for later start times. More middle and high schools have changed their start times to better reflect the sleep research. However, the logistics of changing start times and bus schedules are proving too difficult for some schools leaving many adolescent vulnerable to the negative consequences of sleep deprivation. Troxel et al. (2019) cautions that adolescents should find a middle ground between sleeping too little during the school week and too much during the weekends. Keeping consistent sleep schedules of too little sleep will result in sleep deprivation but oversleeping on weekends can affect the natural biological sleep cycle making it harder to sleep on weekdays.

Adolescent Sexual Activity

By about age ten or eleven, most children experience increased sexual attraction to others that affects social life, both in school and out (McClintock & Herdt, 1996). By the end of high school, more than half of boys and girls report having experienced sexual intercourse at least once, though it is hard to be certain of the proportion because of the sensitivity and privacy of the information. (Center for Disease Control, 2004; Rosenbaum, 2006).

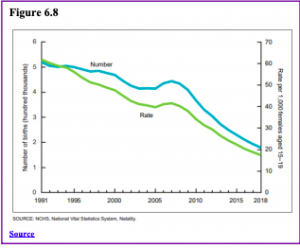

Adolescent Pregnancy: As can be seen in Figure 6.8, in 2018 females aged 15–19 years experienced a birth rate (live births) of 17.4 per 1,000 women. The birth rate for teenagers has declined by 58% since 2007 and 72% since 1991, the most recent peak (Hamilton, Joyce, Martin, & Osterman, 2019). It appears that adolescents seem to be less sexually active than in previous years, and those who are sexually active seem to be using birth control (CDC, 2016).

Risk Factors for Adolescent Pregnancy: Miller, Benson, and Galbraith (2001) found that parent/child closeness, parental supervision, and parents’ values against teen intercourse (or unprotected intercourse) decreased the risk of adolescent pregnancy. In contrast, residing in disorganized/dangerous neighborhoods, living in a lower SES family, living with a single parent, having older sexually active siblings or pregnant/parenting teenage sisters, early puberty, and being a victim of sexual abuse place adolescents at an increased risk of adolescent pregnancy.

Figure 6.8

Consequences of Adolescent Pregnancy: After the child is born life can be difficult for a teenage mother. Only 40% of teenagers who have children before age 18 graduate from high school. Without a high school degree her job prospects are limited, and economic independence is difficult. Teen mothers are more likely to live in poverty, and more than 75% of all unmarried teen mother receive public assistance within 5 years of the birth of their first child. Approximately, 64% of children born to an unmarried teenage high-school dropout live in poverty. Further, a child born to a teenage mother is 50% more likely to repeat a grade in school and is more likely to perform poorly on standardized tests and drop out before finishing high school (March of Dimes, 2012).

Research analyzing the age that men father their first child and how far they complete their education have been summarized by the Pew Research Center (2015) and reflect the research for females. Among dads ages 22 to 44, 70% of those with less than a high school diploma say they fathered their first child before the age of 25. In comparison, less than half (45%) of fathers with some college experience became dads by that age. Additionally, becoming a young father occurs much less for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher as just 14% had their first child prior to age 25. Like men, women with more education are likely to be older when they become mothers.

Eating Disorders

Although eating disorders can occur in children and adults, they frequently appear during the teen years or young adulthood (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2016). Eating disorders affect both genders, although rates among women are 2½ times greater than among men. Similar to women who have eating disorders, men also have a distorted sense of body image, including muscle dysmorphia, which is an extreme desire to increase one’s muscularity (Bosson, Vandello, & Buckner, 2019). The prevalence of eating disorders in the United States is similar among Non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics, African-Americans, and Asians, with the exception that anorexia nervosa is more common among Non-Hispanic Whites (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Wade, Keski-Rahkonen, & Hudson, 2011).

Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: Because of the high mortality rate, researchers are looking into the etiology of the disorder and associated risk factors. Researchers are finding that eating disorders are caused by a complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors (NIMH, 2016). Eating disorders appear to run in families, and researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing eating disorders. Researchers from King’s College London (2019) found that the genetic basis of anorexia overlaps with both metabolic and body measurement traits. The genetic factors also influence physical activity, which may explain the high activity level of those with anorexia. Further, the genetic basis of anorexia overlaps with other psychiatric disorders. Researchers have also found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison with healthy women.

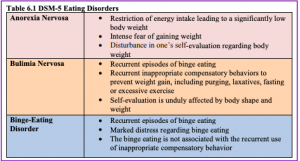

The main criteria for the most common eating disorders: Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and listed in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1

Health Consequences of Eating Disorders: For those suffering from anorexia, health consequences include an abnormally slow heart rate and low blood pressure, which increases the risk for heart failure. Additionally, there is a reduction in bone density (osteoporosis), muscle loss and weakness, severe dehydration, fainting, fatigue, and overall weakness. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder (Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales, & Nielsen, 2011). Individuals with this disorder may die from complications associated with starvation, while others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders.

The binge and purging cycle of bulimia can affect the digestives system and lead to electrolyte and chemical imbalances that can affect the heart and other major organs. Frequent vomiting can cause inflammation and possible rupture of the esophagus, as well as tooth decay and staining from stomach acids. Lastly, binge eating disorder results in similar health risks to obesity, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, heart disease, Type II diabetes, and gall bladder disease (National Eating Disorders Association, 2016).

Eating Disorders Treatment: To treat eating disorders, adequate nutrition and stopping inappropriate behaviors, such as purging, are the foundations of treatment. Treatment plans are tailored to individual needs and include medical care, nutritional counseling, medications (such as antidepressants), and individual, group, and/or family psychotherapy (NIMH, 2016). For example, the Maudsley Approach has parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa be actively involved in their child’s treatment, such as assuming responsibility for feeding the child. To eliminate binge-eating and purging behaviors, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) assists sufferers by identifying distorted thinking patterns and changing inaccurate beliefs.

References

Albert, D., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Adolescent judgment and decision making. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 211– 224.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Fifth Edition). Washington, D. C.: Author.

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724-731.

Birkeland, M. S., Melkivik, O., Holsen, I., & Wold, B. (2012). Trajectories of global self-esteem during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 43-54.

Bosson, J. K., Vandello, J., & Buckner, C. (2019). The psychology of sex and gender. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brass, N., McKellar, North, E., & Ryan, A. (2019). Early adolescents’ adjustment at school: A fresh look at grade and gender differences. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(5), 689-716.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley.

Carney, C., McGehee, D., Harland, K., Weiss, M., & Raby, M. (2015, March). Using naturalistic driving data to assess the prevalence of environmental factors and driver behaviors in teen driver crashes. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. Retrieved from https://www.aaafoundation.org/sites/default/files/2015TeenCrashCausationReport.pdf

Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Caspi, A., Lynam, D., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1993). Unraveling girls’ delinquency: Biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 19-30.

Center for Disease Control. (2004). Trends in the prevalence of sexual behaviors, 1991-2003. Bethesda, MD: Author.

Center for Disease Control. (2016). Birth rates (live births) per 1,000 females aged 15–19 years, by race and Hispanic ethnicity, select years. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/birth-rates-chart-2000-2011-text.htm

Centers for Disease Control. (2018a). Teen drivers: Get the facts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/motorvehiclesafety/teen_drivers/teendrivers_factsheet.html

Centers for Disease Control. (2018b). Trends in the behaviors that contribute to unintentional injury: National Youth Risk Behavioral Survey. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/2017_unintentional_injury_trend_yrbs.pdf

Chein, J., Albert, D., O’Brien, L., Uckert, K., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Developmental Science, 14(2), F1-F10. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Soensens, B., & Van Petegem, S. (2013). Autonomy in family decision making for Chinese adolescents: Disentangling the dual meaning of autonomy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 1184- 1209.

Connolly, J., Craig, W., Goldberg, A., & Pepler, D. (2004). Mixed-gender groups, dating, and romantic relationships in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14, 185-207.

Connolly, J., Furman, W., & Konarski, R. (2000). The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development, 71, 1395–1408.

Costigan, C. L., Cauce, A. M., & Etchinson, K. (2007). Changes in African American mother-daughter relationships during adolescence: Conflict, autonomy, and warmth. In B. J. R. Leadbeater & N. Way (Eds.), Urban girls revisited: Building strengths (pp. 177-201). New York NY: New York University Press.

Côtè, J. E. (2006). Emerging adulthood as an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In J. J. Arnett & J. T. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century, (pp. 85-116). Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association Press.

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

Crooks, K. L., & Baur, K. (2007). Our sexuality (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Crosnoe, R., & Benner, A. D. (2015). Children at school. In M. H. Bornstein, T. Leventhal, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Ecological settings and processes (pp. 268-304). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

De Wit, D. J., Karioja, K., Rye, B. J., & Shain, M. (2011). Perceptions of declining classmate and teacher support following the transition to high school: Potential correlates of increasing student mental health difficulties. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 556-572.

Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214.

Dobbs, D. (2012). Beautiful brains. National Geographic, 220(4), 36. Dolgin, K. G. (2011). The adolescent: Development, relationships, and culture (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Duchesne, S., Larose, S., & Feng, B. (2019). Achievement goals and engagement with academic work in early high school: Does seeking help from teachers matter? Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(2), 222-252.

Dudovitz, R.N., Chung, P.J., Elliott, M.N., Davies, S.L., Tortolero, S,… Baumler, E. (2015). Relationship of age for grade and pubertal stage to early initiation of substance use. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12, 150234. doi:10.5888/pcd12.150234.

Eccles, J. S., & Rosner, R. W. (2015). School and community influences on human development. In M. H. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science (7th ed.). NY: Psychology Press.

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38, 1025-1034.

Euling, S. Y., Herman-Giddens, M.E., Lee, P.A., Selevan, S. G., Juul, A., Sorensen, T. I., Dunkel, L., Himes, J.H., Teilmann, G., & Swan, S.H. (2008). Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics, 121, S172-91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813D.

Eveleth, P. & Tanner, J. (1990). Worldwide variation in human growth (2nd edition). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Furman, W., & Shaffer, L. (2003). The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 3–22). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Garcia, A. R., Metraux, S., Chen, C., Park, J., Culhane, D., & Furstenberg, F. (2018). Patterns of multisystem service use and school dropout among seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-grade students. Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(8), 1041-1073.

Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37. Goodman, G. (2006). Acne and acne scarring: The case for active and early intervention. Australia Family Physicians, 35, 503- 504.

Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262-289.

Grotevant, H. (1987). Toward a process model of identity formation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 2, 203-222

Harter, S. (2006). The self. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3 Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 505-570). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Harter, S. (2012). Emerging self-processes during childhood and adolescence. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney, (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 680-715). New York: Guilford.

Hihara, S., Umemura, T., & Sigimura, K. (2019). Considering the negatively formed identity: Relationships between negative identity and problematic psychosocial beliefs. Journal of Adolescence, 70, 24-32.

Hudson, J. I., Hiripi, E., Pope, H. G., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348-358.

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. (2017). Fatality facts: Teenagers 2016. Retrieved from http://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics/t/teenagers/fatalityfacts/teenagersExternal

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kim-Spoon, J., Longo, G.S., & McCullough, M.E. (2012). Parent-adolescent relationship quality as moderator for the influences of parents’ religiousness on adolescents’ religiousness and adjustment. Journal or Youth & Adolescence, 41 (12), 1576-1578.

King’s College London. (2019). Genetic study revelas metabolic origins of anorexia. Retrieved from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/07/190715164655.htm

Klaczynski, P. (2001). Analytic and heuristic processing influences on adolescent reasoning and decision-making. Child Development, 72 (3), 844-861.

Klauer, S. G., Gun, F., Simons-Morton, B. G., Ouimet, M. C., Lee, S. E., & Dingus, T. A. (2014). Distracted driving a risk of road crashes among novice and experienced drivers. New England Journal of Medicine, 370, 54-59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204142

Kuhn, D. (2013). Reasoning. In. P.D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. (Vol. 1, pp. 744-764). New York NY: Oxford University Press.

Lee, J. C., & Staff, J. (2007). When work matters: The varying impact of work intensity on high school dropout. Sociology of Education, 80(2), 158–178.

Longest, K. C., & Shanahan, M. J. (2007). Adolescent work intensity and substance use: The mediational and moderational roles of parenting. Journal of Family and Marriage, 69(3), 703-720.

Luciano, M., & Collins, P. F. (2012). Incentive motivation, cognitive control, and the adolescent brain: Is it time for a paradigm shift. Child Development Perspectives, 6 (4), 394-399.

March of Dimes. (2012). Teenage pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/teenage-pregnancy.pdf

Marcia, J. (2010). Life transitions and stress in the context of psychosocial development. In T.W. Miller (Ed.), Handbook of stressful transitions across the lifespan (Part 1, pp. 19-34). New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media.

Marsh, H. W., & Kleitman, S. (2005). Consequences of employment during high school: Character building, subversion of academic goals, or a threshold? American Educational Research Journal, 42, 331–369.

McAdams, D. P. (2013). Self and Identity. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from: nobaproject.com.

McClintock, M. & Herdt, G. (1996). Rethinking puberty: The development of sexual attraction. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 5, 178-183.

Meeus, W., Branje, S., & Overbeek, G. J. (2004). Parents and partners in crime: A six-year longitudinal study on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 45(7), 1288-1298. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46,1341–1353. doi:10.1037/a0020205

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2012). Peer relationships and depressive symptomatology in boys at puberty. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 429–435. doi: 10.1037/a0026425

Miller, B. C., Benson, B., & Galbraith, K. A. (2001). Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review, 21(1), 1-38. doi:10.1006/drev.2000.0513

National Center for Health Statistics. (2014). Leading causes of death. Retrieved from: http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10_us.html

National Center for Statistics and Analysis. (2016, May). Young drivers: 2014 data. (Traffic Safety Facts. Report No. DOT HS 812 278). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Retrieved from: http://wwwnrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/812278.pdf

National Eating Disorders Association. (2016). Health consequences of eating disorders. Retrieved from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/health-consequences-eating-disorders

National Institutes of Mental Health. (2016). Eating disorders. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml

National Sleep Foundation. (2016). Teens and sleep. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep topics/teens-and-sleep

Nelson, A., & Spears Brown, C. (2019). Too pretty for homework: Sexualized gender stereotypes predict academic attitudes for gener-typical early adolescent girls. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(4), 603-617.

Office of Adolescent Health. (2018). A day in the life. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/facts-and-stats/day-in-thelife/index.html

Pew Research Center. (2015). College-educated men taking their time becoming dads. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/06/19/college-educated-men-take-their-time-becoming-dads/

Phinney, J. S. (1989). Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 34- 49.

Phinney, J. S. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 499-514. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499

Phinney, J. S. (2006). Ethnic identity exploration. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.) Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st Century. (pp. 117-134) Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Rawatlal, N., Kliewer, W., & Pillay, B. J. (2015). Adolescent attachment, family functioning and depressive symptoms. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 21(3), 80-85. doi:10.7196/SAJP.8252

Rosenbaum, J. (2006). Reborn a virgin: Adolescents’ retracting of virginity pledges and sexual histories. American Journal of Public Health, 96(6), 1098-1103.

Ryan, A. M., Shim, S. S., & Makara, K. A. (2013). Changes in academic adjustment and relational self-worth across the transition to middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1372-1384.

Russell, S. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are teens “post-gay”? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 884–890.

Sadker, M. (2004). Gender equity in the classroom: The unfinished agenda. In M. Kimmel (Ed.), The gendered society reader, 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schwartz, P. D., Maynard, A. M., & Uzelac, S. M. (2008). Adolescent egocentrism: A contemporary view. Adolescence, 43, 441- 447.

Seifert, K. (2012). Educational psychology. Retrieved from http://cnx.org/content/col11302/1.2

Shin, H., & Ryan, A. M. (2014). Early adolescent friendships and academic adjustment: Examining selection and influence processes with longitudinal social network analysis. Developmental Psychology, 50(11), 2462-2472.

Shomaker, L. B., & Furman, W. (2009). Parent-adolescent relationship qualities, internal working models, and attachment styles as predictors of adolescents’ interactions with friends. Journal or Social and Personal Relationships, 2, 579-603.

Sinclair, S., & Carlsson, R. (2013). What will I be when I grow up? The impact of gender identity threat on adolescents’ occupational preferences. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 465-474.

Smetana, J. G. (2011). Adolescents, families, and social development. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. Soller, B. (2014). Caught in a bad romance: Adolescent romantic relationships and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), 56-72.

Staff, J., Schulenberg, J. E., & Bachman, J. G. (2010). Adolescent work intensity, school performance, and academic engagement. Sociology of Education, 83, p. 183–200.

Staff, J., Van Eseltine, M., Woolnough, A., Silver, E., & Burrington, L. (2011). Adolescent work experiences and family formation behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 150-164. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00755.x

Steinberg, L., Icenogle, G., Shulman, E.P., et al. (2018). Around the world, adolescence is a time of heightened sensation seeking and immature self-regulation. Developmental Science, 21, e12532. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12532

Syed, M., & Azmitia, M. (2009). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity during the college years. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19, 601-624. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00609.x

Syed, M., & Juang, L. P. (2014). Ethnic identity, identity coherence, and psychological functioning: Testing basic assumptions of the developmental model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(2), 176-190. doi:10.1037/a0035330

Tartamella, L., Herscher, E., Woolston, C. (2004). Generation extra large: Rescuing our children from the obesity epidemic. New York: Basic Books.

Taylor, J. & Gilligan, C., & Sullivan, A. (1995). Between voice and silence: Women and girls, race and relationship. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Thomas, R. M. (1979). Comparing theories of child development. Santa Barbara, CA: Wadsworth.

Troxel, W. M., Rodriquez, A., Seelam, R., Tucker, J. Shih, R., & D’Amico. (2019). Associations of longitudinal sleep trajectories with risky sexual behavior during late adolescence. Health Psychology. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fhea0000753

Umana-Taylor, A. (2003). Ethnic identity and self-esteem. Examining the roles of social context. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 139-146.

United States Census. (2012). 2000-2010 Intercensal estimates. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/popest/data/index.html

United States Department of Education. (2018). Trends in high school dropout and completion rates in the United States: 2018. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019117.pdf

United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). Employment projections. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_chart_001.htm

United States Department of Labor, Office of Disability Employment Policy. (2019). School based prepatory experiences. Retrieved from: https://www.dol.gov/odep/categories/youth/school.htm

University of California at Los Angeles Medical Center. (2000). Acne. Retrieved from http://www.mednet.ucla.edu

Vaillancourt, M. C., Paiva, A. O., Véronneau, M., & Dishion, T. (2019). How do individual predispositions and family dynamics contribute to academic adjustment through the middle school years? The mediating role of friends’ characteristics. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(4), 576-602.

Wade, T. D., Keski‐Rahkonen, A., & Hudson, J. I. (2011). Epidemiology of eating disorders. Textbook of Psychiatric Epidemiology, Third Edition, 343-360.

Weintraub, K. (2016). Young and sleep deprived. Monitor on Psychology, 47(2), 46-50. Weir, K. (2015). Marijuana and the developing brain. Monitor on Psychology, 46(10), 49-52.

Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44.

Yau, J. C., & Reich, S. M. (2018). “It’s just a lot of work”: Adolescents’ self-presentation norms and practices on Facebook and Instagram. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(1), 196-209.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 6 from Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective Second Edition by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 unported license.