Chapter 29: Cognitive Development in Late Adulthood

Chapter 29 Learning Objectives

- Describe how memory changes for those in late adulthood

- Describe the theories for why memory changes occur

- Describe how cognitive losses in late adulthood are exaggerated

- Explain the pragmatics and mechanics of intelligence

- Define what is a neurocognitive disorder

- Explain Alzheimer’s disease and other neurocognitive disorders

- Describe work and retirement in late adulthood

- Describe how those in late adulthood spend their leisure time

How Does Aging Affect Information Processing?

There are numerous stereotypes regarding older adults as being forgetful and confused, but what does the research on memory and cognition in late adulthood reveal? Memory comes in many types, such as working, episodic, semantic, implicit, and prospective. There are also many processes involved in memory, thus it should not be a surprise that there are declines in some types of memory and memory processes, while other areas of memory are maintained or even show some improvement with age. In this section, we will focus on changes in memory, attention, problem-solving, intelligence, and wisdom, including the exaggeration of losses stereotyped in the elderly.

Memory

Changes in Working Memory: As discussed in chapter 4, working memory is the more active, effortful part of our memory system. Working memory is composed of three major systems: The phonological loop that maintains information about auditory stimuli, the visuospatial sketchpad, that maintains information about visual stimuli, and the central executive, that oversees working memory, allocating resources where needed and monitoring whether cognitive strategies are being effective (Schwartz, 2011). Schwartz reports that it is the central executive that is most negatively impacted by age. In tasks that require allocation of attention between different stimuli, older adults fair worse than do younger adults. In a study by Göthe, Oberauer, and Kliegl (2007) older and younger adults were asked to learn two tasks simultaneously. Young adults eventually managed to learn and perform each task without any loss in speed and efficiency, although it did take considerable practice. None of the older adults were able to achieve this. Yet, older adults could perform at young adult levels if they had been asked to learn each task individually. Having older adults learn and perform both tasks together was too taxing for the central executive. In contrast, working memory tasks that do not require much input from the central executive, such as the digit span test, which uses predominantly the phonological loop, we find that older adults perform on par with young adults (Dixon & Cohen, 2003).

Changes in Long-term Memory: As you should recall, long-term memory is divided into semantic (knowledge of facts), episodic (events), and implicit (procedural skills, classical conditioning, and priming) memories. Semantic and episodic memory is part of the explicit memory system, which requires conscious effort to create and retrieve. Several studies consistently reveal that episodic memory shows greater age-related declines than semantic memory (Schwartz, 2011; Spaniol, Madden, & Voss, 2006). It has been suggested that episodic memories may be harder to encode and retrieve because they contain at least two different types of memory, the event and when and where the event took place. In contrast, semantic memories are not tied to any particular timeline. Thus, only the knowledge needs to be encoded or retrieved (Schwartz, 2011). Spaniol et al. (2006) found that retrieval of semantic information was considerably faster for both younger and older adults than the retrieval of episodic information, with there being little difference between the two age groups for semantic memory retrieval. They note that older adults’ poorer performance on episodic memory appeared to be related to slower processing of the information and the difficulty of the task. They found that as the task became increasingly difficult, the gap between each age groups’ performance increased for episodic memory more so than for semantic memory.

Studies that test general knowledge (semantic memory), such as politics and history (Dixon, Rust, Feltmate, & See, 2007), or vocabulary/lexical memory (Dahlgren, 1998) often find that older adults outperform younger adults. However, older adults do find that they experience more “blocks” at retrieving information that they know. In other words, they experience more tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) events than do younger adults (Schwartz, 2011).

Implicit memory requires little conscious effort and often involves skills or more habitual patterns of behavior. This type of memory shows few declines with age. Many studies assessing implicit memory measure the effects of priming. Priming refers to changes in behavior as a result of frequent or recent experiences. If you were shown pictures of food and asked to rate their appearance and then later were asked to complete words such as s_ _ p, you may be more likely to write soup than soap, or ship. The images of food “primed” your memory for words connected to food. Does this type of memory and learning change with age? The answer is typically “no” for most older adults (Schacter, Church, & Osowiecki, 1994).

Prospective memory refers to remembering things we need to do in the future, such as remembering a doctor’s appointment next week or to take medication before bedtime. It has been described as “the flip-side of episodic memory” (Schwartz, 2011, p. 119). Episodic memories are the recall of events in our past, while the focus of prospective memories is of events in our future. In general, humans are fairly good at prospective memory if they have little else to do in the meantime. However, when there are competing tasks that are also demanding our attention, this type of memory rapidly declines. The explanation given for this is that this form of memory draws on the central executive of working memory, and when this component of working memory is absorbed in other tasks, our ability to remember to do something else in the future is more likely to slip out of memory (Schwartz, 2011). However, prospective memories are often divided into time-based prospective memories, such as having to remember to do something at a future time, or event-based prospective memories, such as having to remember to do something when a certain event occurs. When age-related declines are found, they are more likely to be time-based, than event-based, and in laboratory settings rather than in the real-world, where older adults can show comparable or slightly better prospective memory performance (Henry, MacLeod, Phillips & Crawford, 2004; Luo & Craik, 2008). This should not be surprising given the tendency of older adults to be more selective in where they place their physical, mental, and social energy. Having to remember a doctor’s appointment is of greater concern than remembering to hit the space-bar on a computer every time the word “tiger” is displayed.

Recall versus Recognition: Memory performance often depends on whether older adults are asked to simply recognize previously learned material or recall material on their own. Generally, for all humans, recognition tasks are easier because they require less cognitive energy. Older adults show roughly equivalent memory to young adults when assessed with a recognition task (Rhodes, Castel, & Jacoby, 2008). With recall measures, older adults show memory deficits in comparison to younger adults. While the effect is initially not that large, starting at age 40 adults begin to show declines in recall memory compared to younger adults (Schwartz, 2011).

The Age Advantage: Fewer age differences are observed when memory cues are available, such as for recognition memory tasks, or when individuals can draw upon acquired knowledge or experience. For example, older adults often perform as well if not better than young adults on tests of word knowledge or vocabulary. With age often comes expertise, and research has pointed to areas where aging experts perform quite well. For example, older typists were found to compensate for age-related declines in speed by looking farther ahead at the printed text (Salthouse, 1984). Compared to younger players, older chess experts focus on a smaller set of possible moves, leading to greater cognitive efficiency (Charness, 1981). Accrued knowledge of everyday tasks, such as grocery prices, can help older adults to make better decisions than young adults (Tentori, Osheron, Hasher, & May 2001).

Attention and Problem Solving

Changes in Attention in Late Adulthood: Changes in sensory functioning and speed of processing information in late adulthood often translate into changes in attention (Jefferies et al., 2015). Research has shown that older adults are less able to selectively focus on information while ignoring distractors (Jefferies et al., 2015; Wascher, Schneider, Hoffman, Beste, & Sänger, 2012), although Jefferies and her colleagues found that when given double-time, older adults could perform at young adult levels. Other studies have also found that older adults have greater difficulty shifting their attention between objects or locations (Tales, Muir, Bayer, & Snowden, 2002). Consider the implication of these attentional changes for older adults.

How do changes or maintenance of cognitive ability affect older adults’ everyday lives? Researchers have studied cognition in the context of several different everyday activities. One example is driving. Although older adults often have more years of driving experience, cognitive declines related to reaction time or attentional processes may pose limitations under certain circumstances (Park & Gutchess, 2000). In contrast, research on interpersonal problem solving suggested that older adults use more effective strategies than younger adults to navigate through social and emotional problems (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). In the context of work, researchers rarely find that older individuals perform poorer on the job (Park & Gutchess, 2000). Similar to everyday problem solving, older workers may develop more efficient strategies and rely on expertise to compensate for cognitive decline.

Problem Solving: Problem-solving tasks that require processing non-meaningful information quickly (a kind of task that might be part of a laboratory experiment on mental processes) declines with age. However, many real-life challenges facing older adults do not rely on the speed of processing or making choices on one’s own. Older adults resolve everyday problems by relying on input from others, such as family and friends. They are also less likely than younger adults to delay making decisions on important matters, such as medical care (Strough, Hicks, Swenson, Cheng & Barnes, 2003; Meegan & Berg, 2002).

What might explain these deficits as we age? The processing speed theory, proposed by Salthouse (1996, 2004), suggests that as the nervous system slows with advanced age our ability to process information declines. This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences in many different cognitive tasks. For instance, as we age, working memory becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). Older adults also need a longer time to complete mental tasks or make decisions. Yet, when given sufficient time older adults perform as competently as do young adults (Salthouse, 1996). Thus, when speed is not imperative to the task healthy older adults do not show cognitive declines.

In contrast, inhibition theory argues that older adults have difficulty with inhibitory functioning, or the ability to focus on certain information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information tasks (Hasher & Zacks, 1988). Evidence comes from directed forgetting research. In directed forgetting people are asked to forget or ignore some information, but not other information. For example, you might be asked to memorize a list of words but are then told that the researcher made a mistake and gave you the wrong list and asks you to “forget” this list. You are then given a second list to memorize. While most people do well at forgetting the first list, older adults are more likely to recall more words from the “forget-to-recall” list than are younger adults (Andrés, Van der Linden, & Parmentier, 2004).

Cognitive losses exaggerated: While there are information processing losses in late adulthood, the overall loss has been exaggerated (Garrett, 2015). One explanation is that the type of tasks that people are tested on tend to be meaningless. For example, older individuals are not motivated to remember a random list of words in a study, but they are motivated for more meaningful material related to their life, and consequently perform better on those tests. Another reason is that the research is often cross-sectional. When age comparisons occur longitudinally, however, the amount of loss diminishes (Schaie, 1994). A third reason is that the loss may be due to a lack of opportunity in using various skills. When older adults practiced skills, they performed as well as they had previously. Although diminished performance speed is especially noteworthy in the elderly, Schaie (1994) found that statistically removing the effects of speed diminished the individual’s performance declines significantly. In fact, Salthouse and Babcock (1991) demonstrated that processing speed accounted for all but 1% of age-related differences in working memory when testing individuals from 18 to 82. Finally, it is well established that our hearing and vision decline as we age. Longitudinal research has proposed that deficits in sensory functioning explain age differences in a variety of cognitive abilities (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997). Not surprisingly, more years of education, and subsequently higher income, are associated with the higher cognitive level and slower cognitive decline (Zahodne, Stern, & Manly, 2015).

Intelligence and Wisdom

When looking at scores on traditional intelligence tests, tasks measuring verbal skills show minimal or no age-related declines, while scores on performance tests, which measure solving problems quickly, decline with age (Botwinick, 1984). This profile mirrors crystallized and fluid intelligence. As you recall from the last chapter, crystallized intelligence encompasses abilities that draw upon experience and knowledge. Measures of crystallized intelligence include vocabulary tests, solving number problems, and understanding texts. Fluid intelligence refers to information processing abilities, such as logical reasoning, remembering lists, spatial ability, and reaction time. Baltes (1993) introduced two additional types of intelligence to reflect cognitive changes in aging. Pragmatics of intelligence are cultural exposure to facts and procedures that are maintained as one age and are similar to crystallized intelligence. Mechanics of intelligence are dependent on brain functioning and decline with age, similar to fluid intelligence. Baltes indicated that pragmatics of intelligence show a little decline and typically increase with age.

Additionally, the pragmatics of intelligence may compensate for the declines that occur with the mechanics of intelligence. In summary, global cognitive declines are not as typical as one age, and individuals compensate for some cognitive declines, especially processing speed.

Wisdom is the ability to use accumulated knowledge about practical matters that allow for sound judgment and decision making. A wise person is insightful and has knowledge that can be used to overcome obstacles in living. Does aging bring wisdom? While living longer brings experience, it does not always bring wisdom. Paul Baltes and his colleagues (Baltes & Kunzmann, 2004; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000) suggest that wisdom is rare. In addition, the emergence of wisdom can be seen in late adolescence and young adulthood, with there being few gains in wisdom over the course of adulthood (Staudinger & Gluck, 2011). This would suggest that factors other than age are stronger determinants of wisdom. Occupations and experiences that emphasize others rather than self, along with personality characteristics, such as openness to experience and generativity, are more likely to provide the building blocks of wisdom (Baltes & Kunzmann, 2004). Age combined with certain types of experience and/or personality brings wisdom.

Neurocognitive Disorders

Historically, the term dementia was used to refer to an individual experiencing difficulties with memory, language, abstract thinking, reasoning, decision making, and problem-solving (Erber & Szuchman (2015). However, in the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) the term dementia has been replaced by the neurocognitive disorder. A major neurocognitive disorder is diagnosed as a significant cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains and interferes with independent functioning, while a minor neurocognitive disorder is diagnosed as a modest cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains and does not interfere with independent functioning. There are several different neurocognitive disorders that are typically demonstrated in late adulthood and determining the exact type can be difficult because the symptoms may overlap with each other. Diagnosis often includes a medical history, physical exam, laboratory tests, and changes noted in behavior. Alzheimer’s disease, vascular neurocognitive disorder and neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies will be discussed below.

Alzheimer’s Disease: Probably the most well-known and most common neurocognitive disorder for older individuals is Alzheimer’s disease. In 2016 an estimated 5.4 million Americans were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016), which was approximately one in nine aged 65 and over. By 2050 the number of people age 65 and older with Alzheimer’s disease is projected to be 13.8 million if there are no medical breakthroughs to prevent or cure the disease. Alzheimer’s disease is the 6th leading cause of death in the United States, but the 5th leading cause for those 65 and older. Among the top 10 causes of death in America, Alzheimer’s disease is the only one that cannot be prevented, cured, or even slowed. Current estimates indicate that Alzheimer’s disease affects approximately 50% of those identified with a neurocognitive disorder (Cohen & Eisdorfer, 2011).

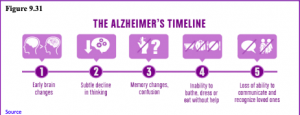

Alzheimer’s disease has a gradual onset with subtle personality changes and memory loss that differs from normal age-related memory problems occurring first. Confusion, difficulty with change, and deterioration in language, problem-solving skills, and personality become evident next. In the later stages, the individual loses physical coordination and is unable to complete everyday tasks, including self-care and personal hygiene (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). Lastly, individuals lose the ability to respond to their environment, to carry on a conversation, and eventually to control movement (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016). On average people with Alzheimer’s survive eight years, but some may live up to 20 years. The disease course often depends on the individual’s age and whether they have other health conditions.

The greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is age, but there are genetic and environmental factors that can also contribute. Some forms of Alzheimer’s are hereditary, and with the early onset type, several rare genes have been identified that directly cause Alzheimer’s. People who inherit these genes tend to develop symptoms in their 30s, 40s, and 50s. Five percent of those identified with Alzheimer’s disease are younger than age 65. When Alzheimer’s disease is caused by deterministic genes, it is called familial Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016). Traumatic brain injury is also a risk factor, as well as obesity, hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes (Carlson, 2011).

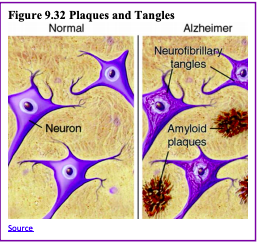

Βeta Amyloid and Tau: According to Erber and Szuchman (2015) the problems that occur with Alzheimer’s disease are due to the “death of neurons, the breakdown of connections between them, and the extensive formation of plaques and tau, which interfere with neuron functioning and neuron survival” (p. 50). Plaques are abnormal formations of protein pieces called beta-amyloid. Beta-amyloid comes from a larger protein found in the fatty membrane surrounding nerve cells. Because beta-amyloid is sticky, it builds up into plaques (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016). These plaques appear to block cell communication and may also trigger an inflammatory response in the immune system, which leads to further neuronal death.

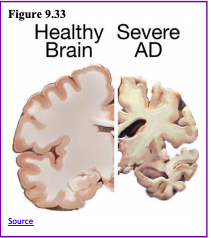

Tau is an important protein that helps maintain the brain’s transport system. When tau malfunctions, it changes into twisted strands called tangles that disrupt the transport system. Consequently, nutrients and other supplies cannot move through the cells and they eventually die. The death of neurons leads to the brain shrinking and affecting all aspects of brain functioning. For example, the hippocampus is involved in learning and memory, and the brain cells in this region are often the first to be damaged. This is why memory loss is often one of the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Figures 9.32 and 9.33 illustrate the difference between an Alzheimer’s brain and a healthy brain.

Washington University School of Medicine (2019) reported that researchers associated with the School of Medicine discovered that failing immune cells, known as microglia, appear to be the link between amyloid and tau, which are the two damaging proteins of Alzheimer’s disease. Amyloid plaques, which appear first, do not cause Alzheimer’s, but the presence of amyloid leads to the formation of tau tangles, which are responsible for the memory loss and cognitive deficits seen in those with Alzheimer’s disease. It appears that weakening microglia causes the amyloid plaques to injure nearby neurons, thus creating a toxic environment that increases the formation and spread of tau tangles. These findings could lead to a new approach for developing therapies for Alzheimer’s.

Sleep Deprivation and Alzheimer’s: Studies suggest that sleep plays a role in clearing both beta-amyloid and tau out of the brain. Shokri-Kojori et al. (2018) scanned participants’ brains after getting a full night’s rest and after 31 hours without sleep. Beta-amyloid increased by about 5% in the participants’ brains after losing a night of sleep. These changes occurred in brain regions that included the thalamus and hippocampus, which are associated with the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Shokri-Kojori et al. also found that participants with the largest increases in beta-amyloid reported the worst mood after sleep deprivation. These findings support other studies that have found that the hippocampus and thalamus are involved in mood disorders.

Additionally, Holth et al. (2019) found that healthy adults who remained awake all day and night had tau levels that were elevated by about 50 percent. Once tau begins to accumulate in brain tissue, the protein can spread from one brain area to the next along with neural connections. Holth et al. also found that older people who had more tau tangles in their brains by PET scanning had a less slow-wave, deep sleep. Holth et al. concluded that good sleep habits and/or treatments designed to encourage plenty of high-quality sleep might play an important role in slowing Alzheimer’s disease. In contrast, poor sleep might worsen the condition and serve as an early warning sign of Alzheimer’s disease.

Healthy Lifestyle Combats Alzheimer’s: Dhana and colleagues with the Rush University Medical Center in Chicago examined how healthy lifestyle mitigates the risk of Alzheimer’s disease (Natanson, 2019). The researchers followed a diverse group of 2765 participants for 9 years and focused on five low-risk lifestyle factors: healthy diet, at least 150 minutes/week of moderate to vigorous physical activity, not smoking, light to moderate alcohol intake, and engaging in cognitively stimulating activities.

Results indicated that those who adopted four or five low-risk lifestyle factors had a 60% lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease when compared with participants who did not follow any or only one of the low-risk factors. The authors concluded that incorporating these lifestyle changes can have a positive effect on one’s brain functioning and lower the risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Vascular Neurocognitive Disorder is the second most common neurocognitive disorder affecting 0.2% in the 65-70 years age group and 16% of individuals 80 years and older (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The vascular neurocognitive disorder is associated with a blockage of cerebral blood vessels that affects one part of the brain rather than a general loss of brain cells seen with Alzheimer’s disease. Personality is not as affected in vascular neurocognitive disorder, and more males are diagnosed than females (Erber and Szuchman, 2015). It also comes on more abruptly than Alzheimer’s disease and has a shorter course before death. Risk factors include smoking, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, or a history of strokes.

Neurocognitive Disorder with Lewy bodies: According to the National Institute on Aging (2015a), Lewy bodies are microscopic protein deposits found in neurons seen postmortem. They affect chemicals in the brain that can lead to difficulties in thinking, movement, behavior, and mood. Neurocognitive Disorder with Lewy bodies is the third most common form and affects more than 1 million Americans. It typically begins at age 50 or older and appears to affect slightly more men than women. The disease lasts approximately 5 to 7 years from the time of diagnosis to death but can range from 2 to 20 years depending on the individual’s age, health, and severity of symptoms. Lewy bodies can occur in both the cortex and brain stem which results in cognitive as well as motor symptoms (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). The movement symptoms are similar to those with Parkinson’s disease and include tremors and muscle rigidity. However, the motor disturbances occur at the same time as the cognitive symptoms, unlike Parkinson’s disease when the cognitive symptoms occur well after the motor symptoms.

Individuals diagnosed with Neurocognitive Disorder with Lewy bodies also experience sleep disturbances, recurrent visual hallucinations, and are at risk for falling.

Work, Retirement, and Leisure

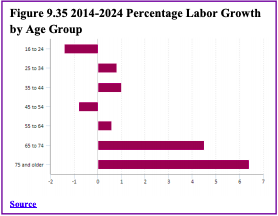

Work: According to the United States Census Bureau, in 1994, approximately 12% of those employed were 65 and over, and by 2016, the percentage had increased to 18% of those employed (McEntarfer, 2019). Looking more closely at the age ranges, more than 40% of Americans in their 60s are still working, while 14% of people in their 70s and just 4% of those 80 and older are currently employed (Livingston, 2019). Even though they make up a smaller number of workers overall, those 65- to 74-year-old and 75-and- older age groups are projected to have the fastest rates of growth in the next decade. See Figure 9.35 for the projected annual growth rate in the labor force by age in percentages, 2014-2024.

Livingston (2019) reported that similar to other age groups, those with higher levels of education are more likely to be employed. Approximately 37% of adults who are 60 and older and have a bachelor’s degree or more are working. In contrast, 31% with some college experience and 21% of those with a high school diploma or less are still working at age 60 and beyond. Additionally, men 60 and older are more likely to be working than women (33% vs. 24%). Not only are older persons working more, but they are also earning more than previously, and their growth in earnings is greater compared to workers of other ages (McEntarfer, 2019).

Older adults are proving just as capable as younger adults at the workplace. In fact, jobs that require social skills, accumulated knowledge, and relevant experiences favor older adults (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). Older adults also demonstrate lower rates of absenteeism and greater investment in their work.

Transitioning into Retirement: For most Americans, retirement is a process and not a one-time event (Quinn & Cahill, 2016). Sixty percent of workers transition straight to bridge jobs, which are often part-time and occur between a career and full retirement. About 15% of workers get another job after being fully retired. This may be due to not having adequate finances after retirement or not enjoying their retirement. Some of these jobs may be in encore careers or work in a different field from the one in which they retired. Approximately 10% of workers begin phasing into retirement by reducing their hours. However, not all employers will allow this due to pension regulations.

Retirement age changes: Looking at retirement data, the average age of retirement declined from more than 70 in 1910 to age 63 in the early 1980s. However, this trend has reversed and the current average age is now 65. Additionally, 18.5% of those over the age of 65 continue to work (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012) compared with only 12% in 1990 (U. S. Government Accountability Office, 2011). With individuals living longer, once retired the average amount of time a retired worker collects social security is approximately 17-18 years (James, Matz-Costa, & Smyer, 2016).

When to retire: Laws often influence when someone decides to retire. In 1986 the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) was amended, and mandatory retirement was eliminated for most workers (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). Pilots, air traffic controllers, federal law enforcement, national park rangers, and firefighters continue to have enforced retirement ages. Consequently, for most workers, they can continue to work if they choose and are able. Social security benefits also play a role. For those born before 1938, they can receive full social security benefits at age 65. For those born between 1943 and 1954, they must wait until age 66 for full benefits, and for those born after 1959, they must wait until age 67 (Social Security Administration, 2016). Extra months are added to those born in years between. For example, if born in 1957, the person must wait until 66 years and 6 months. The longer one waits to receive social security, the more money will be paid out. Those retiring at age 62, will only receive 75% of their monthly benefits. Medicare health insurance is another entitlement that is not available until one is aged 65.

Delayed Retirement: Older adults primarily choose to delay retirement due to economic reasons (Erber & Szchman, 2015). Financially, continuing to work provides not only added income but also does not dip into retirement savings which may not be sufficient. Historically, there have been three parts to retirement income; that is, social security, a pension plan, and individual savings (Quinn & Cahill, 2016). With the 2008 recession, pension plans lost value for most workers. Consequently, many older workers have had to work later in life to compensate for absent or minimal pension plans and personal savings. Social security was never intended to replace full income, and the benefits provided may not cover all the expenses, so elders continue to work. Unfortunately, many older individuals are unable to secure later employment, and those especially vulnerable include persons with disabilities, single women, the oldest- old, and individuals with intermittent work histories.

Some older adults delay retirement for psychological reasons, such as health benefits and social contacts. Recent research indicates that delaying retirement has been associated with helping one live longer. When looking at both healthy and unhealthy retirees, a one-year delay in retiring was associated with a decreased risk of death from all causes (Wu, Odden, Fisher, & Stawski, 2016). When individuals are forced to retire due to health concerns or downsizing, they are more likely to have negative physical and psychological consequences (Erber & Szuchman, 2015).

Retirement Stages: Atchley (1994) identified several phases that individuals go through when they retire:

- Remote pre-retirement phase includes fantasizing about what one wants to do in retirement

- Immediate pre-retirement phase when concrete plans are established

- Actual retirement

- Honeymoon phase when retirees travel and participate in activities they could not do while working

- Disenchantment phase when retirees experience an emotional let-down

- Reorientation phase when the retirees attempt to adjust to retirement by making less hectic plans and getting into a regular routine

Not everyone goes through every stage, but this model demonstrates that retirement is a process.

Post-retirement: Those who look most forward to retirement and have plans are those who anticipate adequate income (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). This is especially true for males who have worked consistently and have a pension and/or adequate savings. Once retired, staying active and socially engaged is important. Volunteering, caregiving, and informal helping can keep seniors engaged. Kaskie, Imhof, Cavanaugh, and Culp (2008) found that 70% of retirees who are not involved in productive activities spent most of their time watching TV, which is correlated with negative affect. In contrast, being productive improves well-being.

Elder Education: Attending college is not just for the young as discussed in the previous chapter. There are many reasons why someone in late adulthood chooses to attend college.

PNC Financial Services surveyed retirees aged 70 and over and found that 58% indicated that they had retired before they had planned (Holland, 2014). Many of these individuals chose to pursue additional training to improve skills to return to work in a second career. Others may be looking to take their career in a new direction. For some older students who no longer are focus on financial reasons, returning to school is intended to enable them to pursue work that is personally fulfilling. Attending college in late adulthood is also a great way for seniors to stay young and keep their minds sharp. Even if an elder chooses not to attend college for a degree, there are many continuing education programs on topics of interest available. In 1975, a nonprofit educational travel organization called Elderhostel began in New Hampshire with five programs for several hundred retired participants (DiGiacomo, 2015). This program combined college classroom time with travel tours and experiential learning experiences. In 2010 the organization changed its name to Road Scholar, and it now serves 100,000 people per year in the U.S. and in 150 countries. Academic courses, as well as practical skills such as computer classes, foreign languages, budgeting, and holistic medicines, are among the courses offered. Older adults who have higher levels of education are more likely to take continuing education. However, offering more educational experiences to a diverse group of older adults, including those who are institutionalized in nursing homes, can bring enhance the quality of life.

Leisure: During the past 10 years, leisure time for Americans 60 and older has remained at about 7 hours a day. However, the amount of time spent on TVs, computers, tablets or other electronic devices has risen almost 30 minutes per day over the past decade (Livingston, 2019). Those 60 and older now spend more than half of their daily leisure time (4 hours and 16 minutes) in front of screens. Screen time has increased for those in their 60s, 70s, 80s and beyond, and across genders and education levels. This rise in screen time coincides with significant growth in the use of digital technology by older Americans. In 2000, 14% of those aged 65 and older used the Internet, and now 73% are users and 53% own smartphones. Alternatively, the time spent on other recreational activities, such as reading or socializing, has gone down slightly. People with less education spend more of their leisure time on screens and less time reading compared with those with more education. Less-educated adults also spend less time exercising: 12 minutes a day for those with a high school diploma or less, compared with 26 minutes for college graduates.

References

Acierno, R., Hernandez, M. A., Amstadter, A. B., Resnick, H. S., Steve, K., Muzzy, W., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 292-297.

Administration on Aging. (2017). 2017 Profile of older Americans. Retrieved from: https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2017OlderAmericansProfile.pdf

Alleccia, J., & Bailey, M. (2019, June 12). A concern for LGBT boomers. The Chicago Tribune, pp. 1-2.

Alterovitz, S. S., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2011). Partner preferences across the lifespan: Online dating by older adults. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1, 89-95.

Alzheimer’s Association. (2016). Know the 10 signs. Early detection matters. Retrieved from: http://www.alz.org/national/documents/tenwarnsigns.pdf

American Federation of Aging Research. (2011). Theories of aging. Retrieved from http://www.afar.org/docs/migrated/111121_INFOAGING_GUIDE_THEORIES_OF_AGINGFR.pdf

American Heart Association. (2014). Overweight in children. Retrieved from http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/HealthyKids/ChildhoodObesity/Overweight-in- Children_UCM_304054_Article.jsp#.V5EIlPkrLIU

American Lung Association. (2018). Taking her breath away: The rise of COPD in women. Retrieved from https://www.lung.org/assets/documents/research/rise-of-copd-in-women-full.pdf

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychological Association. (2016). Older adults’ health and age-related changes. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/aging/resources/guides/older.aspx

Andrés, P., Van der Linden, M., & Parmentier, F. B. R. (2004). Directed forgetting in working memory: Age-related differences. Memory, 12, 248-256.

Antonucci, T. C. (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support and sense of control. In J.E. Birren & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (5th ed., pp. 427–453). New York: Academic Press.

Arias, E., & Xu, J. (2019). United States life tables, 2017. National Vital Statistics Reports, 68(7), 1-66.

Arthritis Foundation. (2017). What is arthritis? Retrieved from http://www.arthritis.org/about-arthritis/understanding- arthritis/what-is-arthritis.php

Ash, A. S., Kroll-Desroisers, A. R., Hoaglin, D. C., Christensen, K., Fang, H., & Perls, T. T. (2015). Are members of long-lived families healthier than their equally long-lived peers? Evidence from the long life family study. Journal of Gerontology: Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. Advance online publication. doi:10.1093/gerona/glv015

Atchley, R. C. (1994). Social forces and aging (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Balducci, L., & Extermann, M. (2000). Management of cancer if the older person: A practical approach. The Oncologist. Retrieved from http://theoncologist.alphamedpress.org/content/5/3/224.full

Baltes, B. B., & Dickson, M. W. (2001). Using life-span models in industrial/organizational psychology: The theory of selective optimization with compensation (soc). Applied Developmental Science, 5, 51-62.

Baltes, P. B. (1993). The aging mind: Potential and limits. The Gerontologist, 33, 580-594.

Baltes, P.B. & Kunzmann, U. (2004). The two faces of wisdom: Wisdom as a general theory of knowledge and judgment about excellence in mind and virtue vs. wisdom as everyday realization in people and products. Human Development, 47(5), 290-299.

Baltes, P. B. & Lindenberger, U. (1997). Emergence of powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: A new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology and Aging, 12, 12–21.

Baltes, P. B., & Staudinger, U. M. (2000). Wisdom: A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. American Psychologist, 55 (1), 122-136.

Barker, (2016). Psychology for nursing and healthcare professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Barnes, S. F. (2011a). Fourth age-the final years of adulthood. San Diego State University Interwork Institute. Retrieved from http://calbooming.sdsu.edu/documents/TheFourthAge.pdf

Barnes, S. F. (2011b). Third age-the golden years of adulthood. San Diego State University Interwork Institute. Retrieved from http://calbooming.sdsu.edu/documents/TheThirdAge.pdf

Bartlett, Z. (2014). The Hayflick limit. Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/8237

Bennett, K. M., Hughes, G. M., & Smith, P. T. (2005). Psychological response to later life widowhood: Coping and the effects of gender. Omega, 51, 33-52.

Benson, J.J., & Coleman, M. (2016). Older adults developing a preference for living apart together. Journal of Marriage and Family, 18, 797-812.

Berger, N. A., Savvides, P., Koroukian, S. M., Kahana, E. F., Deimling, G. T., Rose, J. H., Bowman, K. F., & Miller, R. H. (2006). Cancer in the elderly. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 117, 147-156.

Berk, L. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Blanchard-Fields, F. (2007). Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult development perspective. Current Directions in Psychoogical Science, 16, 26–31

Blank, T. O. (2005). Gay men and prostate cancer: Invisible diversity. American Society of Clinical Oncology, 23, 2593–2596. doi:10.1200/ JCO.2005.00.968

Blazer, D. G., & Wu, L. (2009). The epidemiology of substance use and disorders among middle aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 237-245.

Bookwala, J., Marshall, K. I., & Manning, S. W. (2014). Who needs a friend? Marital status transitions and physical health outcomes in later life. Health Psychology, 33(6), 505-515.

Borysławski, K., & Chmielewski, P. (2012). A prescription for healthy aging. In: A Kobylarek (Ed.), Aging: Psychological, biological and social dimensions (pp. 33-40). Wrocław: Agencja Wydawnicza.

Botwinick, J. (1984). Aging and behavior (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

Bowden, J. L., & McNulty, P. A. (2013). Age-related changes in cutaneous sensation in the healthy human hand. Age (Dordrecht, Netherlannds), 35(4), 1077-1089.

Boyd, K. (2014). What are cataracts? American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved from http://www.aao.org/eye- health/diseases/what-are-cataracts

Boyd, K. (2016). What is macular degeneration? American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved from http://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/amd-macular-degeneration

Brehm, S. S., Miller, R., Perlman, D., & Campbell, S. (2002). Intimate relationships (3rd ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Buman, M. P. (2013). Does exercise help sleep in the elderly? Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/ask-the-expert/does-exercise-help-sleep-the-elderly

Cabeza, R., Anderson, N. D., Locantore, J. K., & McIntosh, A. R. (2002). Aging gracefully: Compensatory brain activity in high- performing older adults. NeuroImage, 17, 1394-1402.

Carlson, N. R. (2011). Foundations of behavioral neuroscience (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Carr, D. (2004a). The desire to date and remarry among older widows and widowers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1051– 1068.

Carr, D. (2004b). Gender, preloss marital dependence, and older adults’ adjustment to widowhood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 220-235.

Carstensen, L. L. (1993). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In J. E. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 209–254). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Carstenson, L. L., Fung, H. H., & Charles, S. T. (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 103-123.

Carstensen, L. L., Gottman, J. M., & Levensen, R. W. (1995). Emotional behavior in long-term marriage. Psychology and Aging, 10, 140–149.

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165–181.

Caruso, C., Accardi, G., Virruso, C., & Candore, G. (2013). Sex, gender and immunosenescence: A key to understand the different lifespan between men and women? Immunity & Ageing, 10, 20.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Persons age 50 and over: Centers for disease control and prevention. Atlanta, GA: Author.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Percent of U. S. adults 55 and over with chronic conditions. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Rationale for regular reporting on health disparities and inequalities—United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60, 3–10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). State-Specific Healthy Life Expectancy at Age 65 Years — United States, 2007–2009. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6228a1.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016b). Older Persons’ Health. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm

Central Intelligence Agency. (2019). The world factbook. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world- factbook/fields/355rank.html

Charness, N. (1981). Search in chess: Age and skill differences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 7, 467.

Cheng, S. (2016). Cognitive reserve and the prevention of dementia: The role of physical and cognitive activities. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(9), 85.

Chmielewski, P., Boryslawski, K., & Strzelec, B. (2016). Contemporary views on human aging and longevity. Anthropological Review, 79(2), 115-142.

Cohen, D., & Eisdorfer, C. (2011). Integrated textbook of geriatric mental health. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Cohen, R. M. (2011). Chronic disease: The invisible illness. AARP. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-06-2011/chronic-disease-invisible-illness.html

Cohn, D., & Passel, J. (2018). A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/05/a-record-64-million-americans-live-in-multigenerational- households/

Craik, F. I., & Bialystok, E. (2006). Cognition through the lifespan: mechanisms of change. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10, 131–138.

Dahlgren, D. J. (1998). Impact of knowledge and age on tip-of-the-tongue rates. Experimental Aging Research, 24, 139-153. Dailey, S., & Cravedi, K. (2006). Osteoporosis information easily accessible NIH senior health. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/newsroom/2006/01/osteoporosis-information-easily-accessible-nihseniorhealth

David, S., & Knight, B. G. (2008). Stress and coping among gay men: Age and ethnic differences. Psychology and Aging, 23, 62– 69. doi:10.1037/ 0882-7974.23.1.62

Davidson, K. (2001). Late life widowhood, selfishness and new partnership choices: A gendered perspective. Ageing and Society, 21, 297–317.

Department of Defense. (2015). Defense advisory committee on women in the services. Retrieved from http://dacowits.defense.gov/Portals/48/Documents/Reports/2015/Annual%20Report/2015%20DACOWITS%20Annual%20Report_Final.pdf

de Vries, B. (1996). The understanding of friendship: An adult life course perspective. In C. Magai & S. H. McFadden (Eds.), Handbook of emotion, adult development, and aging (pp. 249–268). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

DiGiacomo, R. (2015). Road scholar, once elderhostel, targets boomers. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/nextavenue/2015/10/05/road-scholar-once-elderhostel-targets-boomers/#fcb4f5b64449

Dixon R. A., & Cohen, A. L. (2003). Cognitive development in adulthood. In R. M. Lerner, M. A. Easterbrokks & J. Misty (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (pp. 443-461). Hoboken NJ: John Wiley.

Dixon, R. A., Rust, T. B., Feltmate, S. E., & See, S. K. (2007). Memory and aging: Selected research directions and application issues. Canadian Psychology, 48, 67-76.

Dollemore, D. (2006, August 29). Publications. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved from http://www.nia.nih.gov/HealthInformation/Publications?AgingUndertheMicroscope/

Economic Policy Institute. (2013). Financial security of elderly Americans at risk. Retrieved from http://www.epi.org/publication/economic-security-elderly-americans-risk

Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. (2008). The effect of widowhood on mortality by the causes of death of both spouses. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 2092-2098.

Erber, J. T., & Szuchman, L. T. (2015). Great myths of aging. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York, NY: Norton & Company.

Farrell, M. J. (2012). Age-related changes in the structure and function of brain regions involved in pain processing. Pain Medication, 2, S37-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01287.x.

Federal Bureau of Investigation.üü (2014). Crime in the United States. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the- u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.s.-2014/tables/expanded- homicide- data/expanded_homicide_data_table_1_murder_victims_by_race_ethnicity_and_sex_2014.xls

Fingerman, K. L., & Birditt, K. S. (2011). Relationships between adults and their aging parents. In K. W. Schaie & S. I Willis (Eds.). Handbook of the psychology of aging (7th ed.) (pp 219-232). SanDiego: Elsevier Academic Press.

Fischer, C. S. (1982). To dwell among friends: Personal networks in town and city. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Fjell, A. M., & Walhovd, K. B. (2010). Structural brain changes in aging: Courses, causes, and cognitive consequences. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 21, 187-222.

Fox, S. (2004). Older Americans and the Internet. PEW Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/report_display.asp?r_117

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H. J., Emlet, C. A., Muraco, A., Erosheva, E. A., Hoy-Ellis, C. P.,… Petry, H. (2011). The aging and health report: disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Seattle, WA: Institute for Multigenerational Health.

Garrett, B. (2015). Brain and behavior (4th ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gatz, M., Smyer, M. A., & DiGilio, D. A. (2016). Psychology’s contribution to the well-being of older Americans. American Psychologist, 71(4), 257-267.

Gems, D. (2014). Evolution of sexually dimorphic longevity in humans. Aging, 6, 84-91.

George, L.K. (2009). Still happy after all these years: research frontiers on subjective well-being in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 65B (3), 331–339. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbq006

Githens, K., & Abramsohn, E. (2010). Still got it at seventy: Sexuality, aging, and HIV. Achieve, 1, 3-5.

Glaser, K., Stuchbury, R., Tomassini, C., & Askham, J. (2008). The long-term consequences of partnership dissolution for support in later life in the Unites Kingdom. Ageing & Society, 28(3), 329-351.

Gosney, T. A. (2011). Sexuality in older age: Essential considerations for healthcare professionals. Age Ageing, 40(5), 538-543. Göthe, K., Oberauer, K., & Kliegl, R. (2007). Age differences in dual-task performance after practice. Psychology and Aging, 22, 596-606.

Goyer, A. (2010). More grandparents raising grandkids: New census data shows and increase in children being raised by extended family. AARP. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/relationships/grandparenting/info-12- 2010/more_grandparents_raising_grandchildren.html

Graham, J. (2019, July 10). Why many seniors rate their health positively. The Chicago Tribune, p. 2.

Greenfield, E. A., Vaillant, G. E., & Marks, N. F. (2009). Do formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions have independent linkages with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 196-212.

Guinness World Records. (2016). Oldest person (ever). Retrieved from http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/search?term=oldest+person+%28ever%29

Ha, J. H. (2010). The effects of positive and negative support from children on widowed older adults’ psychological adjustment: A longitudinal analysis. Gerontologist, 50, 471-481.

Harkins, S. W., Price, D. D. & Martinelli, M. (1986). Effects of age on pain perception. Journal of Gerontology, 41, 58-63.

Harvard School of Public Health. (2016). Antioxidants: Beyond the hype. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/antioxidants

Hasher, L. & Zacks, R. T. (1988). Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In G.H. Bower (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, (Vol. 22, pp. 193–225). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

He, W., Goodkind, D., & Kowal, P. (2016). An aging world: 2015. International Population Reports. U.S. Census Bureau.

He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (2005.). U. S. Census Bureau, Current Popluation Reports, P23-209, 65+ in the United States: 2005 (United States, U. S. Census Bureau). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p23- 190/p23-190.html

Hendricks, J., & Cutler, S. J. (2004). Volunteerism and socioemotional selectivity in later life. Journal of Gerontology, 59B, S251-S257.

Henry, J. D., MacLeod, M. S., Phillips, L. H., & Crawford, J. R. (2004). A meta-analytic review of prospective memory and aging. Psychology and Aging, 19, 27–39.

Heron, M. (2018). Deaths: Leading causes 2016. National Vital Statistics Reports, 67(6), 1-77.

Hillman, J., & Hinrichsen, G. A. (2014). Promoting and affirming competent practice with older lesbian and gay adults. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(4), 169-277.

Hinze, S. W., Lin, J., & Andersson, T. E. (2012). Can we capture the intersections? Older black women, education, and health. Women’s Health Issues, 22, e91-e98.

Hirokawa K., Utsuyama M., Hayashi, Y., Kitagawa, M., Makinodan, T., & Fulop, T. (2013). Slower immune system aging in women versus men in the Japanese population. Immunity & Ageing, 10(1), 19.

Holland, K. (2014). Why America’s campuses are going gray? Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/2014/08/28/why-americas- campuses-are-going-gray.html

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of psychosomatic research, 11, 213.

Holth, J., Fritschi, S., Wang, C., Pedersen, N., Cirrito, J., Mahan, T.,…Holtzman, D. 2019). The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Science, 363(6429), 880-884.

Hooyman, N. R., & Kiyak, H. A. (2011). Social gerontology: A multidisciplinary perspective (9th Ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson James, J. B., Matz-Costa, C., & Smyer, M. A. (2016). Retirement security: It’s not just about the money. American Psychologist, 71(4), 334-344.

Jarrett, C. (2015). Great myths of the brain. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Jefferies, L. N., Roggeveen, A. B., Ennis, J. T., Bennett, P. J., Sekuler, A. B., & Dilollo, V. (2015). On the time course of attentional focusing in older adults. Psychological Research, 79, 28-41.

Jensen, M. P., Moore, M. R., Bockow, T. B., Ehde, D. M., & Engel, J. M. (2011). Psychosocial factors and adjustment to persistent pain in persons with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 92, 146–160. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010 .09.021

Jin, K. (2010). Modern biological theories of aging. Aging and Disease, 1, 72-74.

Kahana, E., Bhatta, T., Lovegreen, L. D., Kahana, B., & Midlarsky, E. (2013). Altruism, helping, and volunteering: Pathways to well-being in late life. Journal of Aging and Health, 25(1), 159-187.

Kahn, R. L., & Antonucci, T. C. (1980). Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support. In P. B. Baltes & O. G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (pp. 253–286). New York: Academic Press.

Kane, M. (2008). How are sexual behaviors of older women and older men perceived by human service students? Journal of Social Work Education, 27(7), 723-743.

Karraker, A., DeLamater, J., & Schwartz, C. R. (2011). Sexual frequency decline from midlife to later life. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B, 502-512.

Kaskie, B., Imhof, S., Cavanaugh, J., & Culp, K. (2008). Civic engagement as a retirement role for aging Americans. The Gerontologist, 48, 368-377.

Kemp, E. A., & Kemp, J. E. (2002). Older couples: New romances: Finding and keeping love in later life. Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts.

King, V., & Scott, M. E. (2005). A comparison of cohabitating relationships among older and younger adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 271-285.

Kolb, B., & Whishaw, I. Q. (2011). An introduction to brain and behavior (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

Kosberg, J. I. (2014). Reconsidering assumptions regarding men an elder abuse perpetrators and as elder abuse victims. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 26, 207-222.

Kowalski, S. D., & Bondmass, M. D. (2008). Physiological and psychological symptoms of grief in widows. Research in Nursing and Health, 31(1), 23-30.

Kramer, A. F. & Erickson, K. I. (2007). Capitalizing on cortical plasticity: The influence of physical activity on cognition and brain function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 342–348.

Lang, F. R., & Schütze, Y. (2002). Adult children’s supportive behaviors and older adults’ subjective well-being: A developmental perspective on intergenerational relationships. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 661-680.

Laslett, P. (1989). A fresh map of life: The emergence of the third age. London, UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Lee, S.B., Oh, J.G., Park, J.H., Choi, S.P., & Wee, J.H. (2018). Differences in youngest-old, middle-old, and oldest-old patients who visit the emergency department. Clinical and Experimental Emergency Medicine, 5(4), 249-255.

Lee, S. J., Steinman, M., & Tan, E. J. (2011). Volunteering, driving status, and mortality in U.S. retirees. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 59 (2), 274-280. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03265x

Lemon, F. R., Bengston, V. L., & Peterson, J. A. (1972). An exploration of activity theory of aging: Activity types and life satisfaction among in-movers to a retirement community. Journal of Geronotology, 27, 511-523.

Levant, S., Chari, K., & DeFrances, C. J. (2015). Hospitalizations for people aged 85 and older in the United States 2000-2010. Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db182.pdf

Levy, B. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 332-336.

Lichtenberg, P. A. (2016). Financial exploitation, financial capacity, and Alzheimer’s disease. American Psychologist, 71(4), 312-320.

Lin, I. F. (2008). Consequences of parental divorce for adult children’s support of their frail parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(1), 113-128.

Livingston, G. (2019). Americans 60 and older are spending more time in front of their screens than a decade ago. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/18/americans-60-and-older-are-spending-more-time-in-front-of- their-screens-than-a-decade-ago/

Luo, L., & Craik, F. I. M. (2008). Aging and memory: A cognitive approach. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 53, 346-353. Martin, L. J. (2014). Age changes in the senses. MedlinePlus. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004013.htm

Martin, P., Poon, L.W., & Hagberg, B. (2011). Behavioral factors of longevity. Journal of Aging Research, 2011/2012, 1–207.

Mayer, J. (2016). MyPlate for older adults. Nutrition Resource Center on Nutrition and Aging and the U. S. Department of Agriculture Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging and Tufts University. Retrieved from http://nutritionandaging.org/my-plate-for-older-adults/

McCormak A., Edmondson-Jones M., Somerset S., & Hall D. (2016) A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hearing Research, 337, 70-79.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1988). Physiological resilience among widowed men and women: A 10 year follow-up study of a national sample. Journal of Social Issues, 44(3), 129-142.

McDonald, L., & Robb, A. L. (2004). The economic legacy of divorce and separation for women in old age. Canadian Journal on Aging, 23, 83-97.

McEntarfer, E. (2018). Older people working longer, earning more. Retrieved from http://thepinetree.net/new/?p=58015

Meegan, S. P., & Berg, C. A. (2002). Contexts, functions, forms, and processes of collaborative everyday problem solving in older adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26(1), 6-15. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000283

Molton, I. R., & Terrill, A. L. (2014). Overview of persistent pain in older adults. American Psychologist, 69(2), 197-207. Natanson, H. (2019, July 14). To reduce risk of Alzheimer’s play chess and ditch red meat. The Chicago Tribune, p. 1.

National Council on Aging. (2019). Healthy aging facts. Retrieved from https://www.ncoa.org/news/resources-for-reporters/get- the-facts/healthy-aging-facts/

National Council on Alcoholism and Drug. (2015). Alcohol, drug dependence and seniors. Retrieved from https://www.ncadd.org/about-addiction/seniors/alcohol-drug-dependence-and-seniors

National Eye Institute. (2016a). Cataract. Retrieved from https://nei.nih.gov/health/cataract/

National Eye Institute. (2016b). Glaucoma. Retrieved from https://nei.nih.gov/glaucoma/

National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. (2006). Make room for all: Diversity, cultural competency and discrimination in an aging America. Washington, DC: The Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

National Institutes of Health. (2011). What is alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency? Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/aat

National Institutes of Health. (2013). Hypothyroidism. Retrieved from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health- topics/endocrine/hypothyroidism/Pages/fact-sheet.aspx

National Institutes of Health. (2014a). Aging changes in hormone production. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004000.htm

National Institutes of Health. (2014b). Cataracts. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/cataract.html

National Institutes of Health. (2014c). Prescription and illicit drug abuse. NIH Senior Health: Built with you in mind. Retrieved from http://nihseniorhealth.gov/drugabuse/illicitdrugabuse/01.html

National Institutes of Health. (2015a). Macular degeneration. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/maculardegeneration.html

National Institutes of Health. (2015b). Pain: You can get help. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/pain

National Institutes of Health. (2016). Quick statistics about hearing. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing

National Institutes of Health: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2014). Arthritis and rheumatic diseases. Retrieved from https://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Arthritis/arthritis_rheumatic.asp

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health. (2013). What is COPD? Retrieved from http://nihseniorhealth.gov/copd/whatiscopd/01.html

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health. (2015). What is osteoporosis? http://nihseniorhealth.gov/osteoporosis/whatisosteoporosis/01.html

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health (2016a). Problems with smell. Retrieved from https://nihseniorhealth.gov/problemswithsmell/aboutproblemswithsmell/01.html

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health (2016b). Problems with taste. Retrieved from https://nihseniorhealth.gov/problemswithtaste/aboutproblemswithtaste/01.html

National Institute on Aging. (2011a). Biology of aging: Research today for a healthier tomorrow. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/biology-aging/preface

National Institute on Aging. (2011b). Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging Home Page. (2011). Retrieved from http://www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/blsa/blsa.htm

National Institute on Aging. (2012). Heart Health. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/heart-health

National Institute on Aging. (2013). Sexuality later in life. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/sexuality- later-life

National Institute on Aging. (2015a). The Basics of Lewy Body Dementia. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/lewy-body-dementia/basics-lewy-body-dementia

National Institute on Aging. (2015b). Global Health and Aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/global-health-and-aging/living-longer

National Institute on Aging. (2015c). Hearing loss. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/hearing-loss

National Institute on Aging. (2015d). Humanity’s aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/global- health-and-aging/humanitys-aging

National Institute on Aging. (2015e). Shingles. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/shingles

National Institute on Aging. (2015f). Skin care and aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/skin-care- and-aging

National Institute on Aging. (2016). A good night’s sleep. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/good- nights-sleep

National Library of Medicine. (2014). Aging changes in body shape. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003998.htm

National Library of Medicine. (2019). Aging changes in the heart and blood vessels. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004006.htm

National Osteoporosis Foundation. (2016). Preventing fractures. Retrieved from https://www.nof.org/prevention/preventing- fractures/

National Sleep Foundation. (2009). Aging and sleep. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep-topics/aging- and-sleep

Nelson, T. D. (2016). Promoting healthy aging by confronting ageism. American Psychologist, 71(4), 276-282.

Novotney, A. (2019). Social isolation: It could kill you. Monitor on Psychology, 50(5), 33-37.

Office on Women’s Health. (2010a). Raising children again. Retrieved from http://www.womenshealth.gov/aging/caregiving/raising-children-again.html

Office on Women’s Health. (2010b). Sexual health. Retrieved from http://www.womenshealth.gov/aging/sexual-health/

Olanow, C. W., & Tatton, W. G. (1999). Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 22, 123-144.

Ortman, J. M., Velkoff, V. A., & Hogan, H. (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States. United States Census. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

Overstreet, L. (2006). Unhappy birthday: Stereotypes in late adulthood. Unpublished manuscript, Texas Woman’s University.

Owsley, C., Rhodes, L. A., McGwin Jr., G., Mennemeyer, S. T., Bregantini, M., Patel, N., … Girkin, C. A. (2015). Eye care quality and accessibility improvement in the community (EQUALITY) for adults at risk for glaucoma: Study rationale and design. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 1-14. DOI 10:1186/s12939-015-0213-8

Papernow, P. L. (2018). Recoupling in midlife and beyond: From love at last to not so fast. Family Processes, 57(1), 52-69. Park, D. C. & Gutchess, A. H. (2000). Cognitive aging and everyday life. In D.C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive Aging: A Primer (pp. 217–232). New York: Psychology Press.

Park, D. C., & Reuter-Lorenz, P. (2009). The adaptive brain: Aging and neurocognitive scaffolding. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 173-196.

Pew Research Center. (2011). Fighting poverty in a tough economy. Americans move in with their relatives. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files.2011/10.Multigenerationsl-Households-Final1.pdf

Pilkington, P. D., Windsor, T. D., & Crisp, D. A. (2012). Volunteerism and subjective well-being in midlife and older adults: The role of supportive social networks. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 67 B (2), 249- 260. Doi:10.1093/geronb/grb154.

Quinn, J. F., & Cahill, K. E. (2016). The new world of retirement income security in America. American Psychologist, 71(4), 321-333.

Resnikov, S., Pascolini, D., Mariotti, S. P., & Pokharel, G. P. (2004). Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82, 844-851.

Rhodes, M. G., Castel, A. D., & Jacoby, L. L. (2008). Associative recognition of face pairs by younger and older adults: The role of familiarity-based processing. Psychology and Aging, 23, 239-249.

Riediger, M., Freund, A.M., & Baltes, P.B. (2005). Managing life through personal goals: Intergoal facilitation and intensity of goal pursuit in younger and older adulthood. Journals of Gerontology, 60B, P84-P91.

Roberto, K. A. (2016). The complexities of elder abuse. American Psychologist, 71(4), 302-311.

Robin, R. C. (2010). Grown-up, but still irresponsible. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/10weekinreview/10rabin.html>.

Robins, R.W., & Trzesniewski, K.H. (2005). Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 (3), 158-162. DOI: 10.1111/j.0963- 7214.2005.00353x

Rowe, J. W. & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440.

Rubinstein, R.L. (2002). The third age. In R.S. Weiss & S.A. Bass (Eds.), Challenges of the third age; Meaning and purpose in later life (pp. 29-40). New York: Oxford University Press.

Ruckenhauser, G., Yazdani, F., & Ravaglia, G. (2007). Suicide in old age: Illness or autonomous decision of the will? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 44(6), S355-S358.

Saiidi, U. (2019). US life expectancy has been declining. Here’s why. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2019/07/09/us-life- expectancy-has-been-declining-heres-why.html

Salthouse, T. A. (1984). Effects of age and skill in typing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113, 345.

Salthouse, T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103, 403-428. Salthouse, T. A. (2004). What and when of cognitive aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(4), 140-144.

Salthouse, T. A., & Babcock, R. L. (1991). Decomposing adult age differences in working memory. Developmental Psychology, 27, 763-776.

Schacter, D. L., Church, B. A., & Osowiecki, D. O. (1994). Auditory priming in elderly adults: Impairment of voice-specific implicit memory. Memory, 2, 295-323.

Schaie, K. W. (1994). The course of adult intellectual development. American Psychologist, 49, 304-311.

Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., Middlestadt, S. E., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). Sexual behaviors, condom use, and sexual health of Americans over 50: Implications for sexual health promotion for older adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(5), 315-329.

Schwartz, B. L. (2011). Memory: Foundations and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Scott, P. J. (2015). Save the Males. Men’s Health. Retrieved from http://www.menshealth.com

Shmerling, R. H. (2016). Why men often die earlier than women. Harvard Health Publications. Retrieved from http://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/why-men-often-die-earlier-than-women-201602199137

Shokri-Kojori, E., Wang, G., Wiers, C., Demiral, S., Guo, M., Kim, S.,…Volkow, N. (2018). β-amyloid accumulation in the human brain after one night of sleep deprivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(17), 4483-4488.

Singer, T., Verhaeghen, P., Ghisletta, P., Lindenberger, U., & Baltes, P.B. (2003). The fate of cognition in very old age: Six-year longitudinal findings in the Berlin Aging Study (BASE). Psychology and Aging, 18, 318-331.

Siriwardena, A. N., Qureshi, A., Gibson, S., Collier, S., & Lathamn, M. (2006). GP’s attitudes to benzodiazepine and “z-drug” prescribing: A barrier to implementation of evidence and guidance on hypnotics. British Journal of General Practice, 56, 964-967.

Smith, J. (2000). The fourth age: A period of psychological mortality? Max Planck Forum, 4, 75-88.

Social Security Administration. (2016). Retirement planner: Benefits by year of birth. Retrieved from https://www.ssa.gov/planners/retire/agereduction.html

Sohn, H. (2015). Health insurance and divorce: Does having your own insurance matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 982-995.

Spaniol, J., Madden, D. J., & Voss, A. (2006). A diffusion model analysis of adult age differences in episodic and semantic long- term memory retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32(1). 101-117.

Staudinger, U. M., & Gluck, J. (2011). Psychological wisdom research: Commonalities and differences in a growing field. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 215–241.

Stepler, R. (2016a). Gender gap in share of older adults living alone narrows. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/02/18/1-gender-gap-in-share-of-older-adults-living-alone-narrows/

Stepler, R. (2016b). Living arrangements of older adults by gender. Pew Research Center Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/02/18/2-living-arrangements-of-older-americans-by-gender/

Stepler, R. (2016c). Smaller share of women 65 or older are living alone. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/02/18/smaller-share-of-women-ages-65-and-older-are-living-alone/

Stepler, R. (2016d). Well-being of older adults living alone. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/02/18/3-well-being-of-older-adults-living-alone/

Stepler, R. (2016e). World’s centenarian population projected to grow eightfold by 2050. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/04/21/worlds-centenarian-population-projected-to-grow-eightfold-by- 2050/

Stoller, E. P., & Longino, C. F. (2001). “Going home” or “leaving home”? The impact of person and place ties on anticipated counterstream migration. Gerontologist, 41, 96-102.

Strait, J.B., & Lakatta, E.G. (2012). Aging-associated cardiovascular changes and their relationship to heart failure. Heart Failure Clinics, 8(1), 143-164.

Strine, T. W., Hootman, J. M., Chapman, D. P., Okoro, C. A., & Balluz, L. (2005). Health-related quality of life, health risk behaviors, and disability among adults with pain-related activity difficulty. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 2042–2048. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005 .066225

Strough, J., Hicks, P. J., Swenson, L. M., Cheng, S., & Barnes, K. A. (2003). Collaborative everyday problem solving: Interpersonal relationships and problem dimensions. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 56, 43- 66.

Subramanian, S. V., Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. (2008). Widowhood and mortality among the elderly: The modifying role of neighborhood concentration of widowed individuals. Social Science and Medicine, 66, 873-884.

Sullivan, A. R., & Fenelon, A. (2014). Patterns of widowhood mortality. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 69B, 53-62.

Tales, A., Muir, J. L., Bayer, A., & Snowden, R. J. (2002). Spatial shifts in visual attention in normal aging and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neuropsychologia, 40, 2000-2012.

Taylor, R., Chatters, L. & Leving, J. (2004). Religion in the lives of African Americans. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Tennstedt, S., Morris, J., Unverzagt, F., Rebok, G., Willis, S., Ball, K., & Marsiske, M. (2006). ACTIVE: Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly Clinical Trial. Clinical Trials Database and Worldwide Listings. Retrieved from http://www.clinicaltrialssearch.org/active-advanced-cognitive-training-for-independent-and-vital-elderly- nct00298558.html

Tentori, K., Osherson, D., Hasher, L., & May, C. (2001). Wisdom and aging: Irrational preferences in college students but not older adults. Cognition, 81, B87–B96.

Thornbury, J. M., & Mistretta, C. M. (1981). Tactile sensitivity as a function of age. Journal of Gerontology, 36(1), 34-39.

Tobin, M., K., Musaraca, K., Disouky, A., Shetti, A., Bheri, A. Honer, W. G.,…Lazarov, O. (2019). Human hippocampal neurogenesis persists in aged adults and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Cell Stem Cell, 24(6), 974-982.

Tsang, A., Von Korff, M., Lee, S., Alonso, J., Karam, E., Angermeyer, M. C., . . . Watanabe, M. (2008). Common persistent pain conditions in developed and developing countries: Gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression- anxiety disorders. The Journal of Pain, 9, 883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

United States Census Bureau. (2012). 2012 national population projections. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/natiobnal/2012.html

United States Census Bureau. (2014a). American Community Survey, 2014 Estimates: table B10001. Retrieved from at http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_14_5YR_B10001&prodType=t able

United States Census Bureau. (2014b). U. S. population projections: 2014-2060. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/natiobnal/2014.html