Chapter 9: People of Color, White Identity, & Women

Learning Objectives

-

Distinguish prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination.

-

Distinguish old-fashioned, blatant biases from contemporary, subtle biases.

-

Understand old-fashioned biases such as social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism.

-

Understand subtle, unexamined biases that are automatic, ambiguous, and ambivalent.

-

Understand 21st-century biases that may break down as identities get more complicated.

9.1 Introduction to Prejudice, Discrimination, and Stereotyping

People are often biased against others outside of their own social group, showing prejudice (emotional bias), stereotypes (cognitive bias), and discrimination (behavioral bias). In the past, people used to be more explicit with their biases, but during the 20th century, when it became less socially acceptable to exhibit bias, such things like prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination became more subtle (automatic, ambiguous, and ambivalent). In the 21st century, however, with social group categories even more complex, biases may be transforming once again.

You are an individual, full of beliefs, identities, and more that help makes you unique. You don’t want to be labeled just by your gender or race or religion. But as complex, as we perceive ourselves to be, we often define others merely by their most distinct social group.

Even in one’s own family, everyone wants to be seen for who they are, not as “just another typical X.” But still, people put other people into groups, using that label to inform their evaluation of the person as a whole—a process that can result in serious consequences. This module focuses on biases against social groups, which social psychologists sort into emotional prejudices, mental stereotypes, and behavioral discrimination. These three aspects of bias are related, but they each can occur separately from the others (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2010; Fiske, 1998). For example, sometimes people have a negative, emotional reaction to a social group (prejudice) without knowing even the most superficial reasons to dislike them (stereotypes).

This module shows that today’s biases are not yesterday’s biases in many ways, but at the same time, they are troublingly similar. First, we’ll discuss old-fashioned biases that might have belonged to our grandparents and great-grandparents—or even the people nowadays who have yet to leave those wrongful times. Next, we will discuss late 20th century biases that affected our parents and still linger today. Finally, we will talk about today’s 21st-century biases that challenge fairness and respect for all.

Old-fashioned Biases: Almost Gone

You would be hard-pressed to find someone today who openly admits they don’t believe inequality. Regardless of one’s demographics, most people believe everyone is entitled to the same, natural rights. However, as much as we now collectively believe this, not too far back in our history, this idea of equality was an unpracticed sentiment. Of all the countries in the world, only a few have equality in their constitution and those who do originally defined it for a select group of people.

At the time, old-fashioned biases were simple: people openly put down those not from their own group. For example, just 80 years ago, American college students unabashedly thought Turkish people were “cruel, very religious, and treacherous” (Katz & Braly, 1933). So where did they get those ideas, assuming that most of them had never met anyone from Turkey? Old-fashioned stereotypes were overt, unapologetic, and expected to be shared by others—what we now call “blatant biases.”

Blatant biases are conscious beliefs, feelings, and behavior that people are perfectly willing to admit, which mostly express hostility toward other groups (outgroups) while unduly favoring one’s own group (in-group). For example, organizations that preach contempt for other races (and praise for their own) is an example of blatant bias. And scarily, these blatant biases tend to run in packs: People who openly hate one outgroup also hate many others. To illustrate this pattern, we turn to two personality scales next.

Social Dominance Orientation

Social dominance orientation (SDO) describes a belief that group hierarchies are inevitable in all societies and are even a good idea to maintain order and stability (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Those who score high on SDO believe that some groups are inherently better than others, and because of this, there is no such thing as group “equality.” At the same time, though, SDO is not just about being personally dominant and controlling of others; SDO describes a preferred arrangement of groups with some on top (preferably one’s own group) and some on the bottom. For example, someone high in SDO would likely be upset if someone from an outgroup moved into his or her neighborhood. It’s not that the person high in SDO wants to “control” what this outgroup member does; it’s that moving into this “nice neighborhood” disrupts the social hierarchy the person high in SDO believes in (i.e. living in a nice neighborhood denotes one’s place in the social hierarchy—a place reserved for one’s in-group members).

Although research has shown that people higher in SDO are more likely to be politically conservative, there are other traits that more strongly predict one’s SDO. For example, researchers have found that those who score higher on SDO are usually lower than average on tolerance, empathy, altruism, and community orientation. In general, those high in SDO have a strong belief in work ethic—that hard work always pays off and leisure is a waste of time. People higher on SDO tend to choose and thrive in occupations that maintain existing group hierarchies (police, prosecutors, business), compared to those lower in SDO, who tend to pick more equalizing occupations (social work, public defense, psychology).

The point is that SDO—a preference for inequality as normal and natural—also predicts endorsing the superiority of certain groups: men, native-born residents, heterosexuals, and believers in the dominant religion. This means seeing women, minorities, homosexuals, and non-believers as inferior. Understandably, the first list of groups tend to score higher on SDO, while the second group tends to score lower. For example, the SDO gender difference (men higher, women lower) appears all over the world.

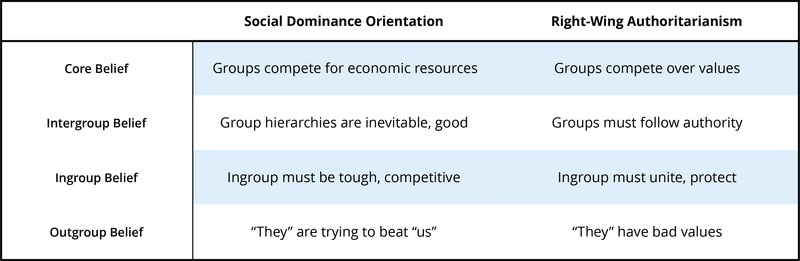

At its heart, SDO rests on a fundamental belief that the world is tough and competitive with only a limited number of resources. Thus, those high in SDO see groups as battling each other for these resources, with winners at the top of the social hierarchy and losers at the bottom (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Right-wing Authoritarianism

Right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) focuses on value conflicts, whereas SDO focuses on the economic ones. That is, RWA endorses respect for obedience and authority in the service of group conformity (Altemeyer, 1988). Returning to an example from earlier, the homeowner who’s high in SDO may dislike the outgroup member moving into his or her neighborhood because it “threatens” one’s economic resources (e.g. lowering the value of one’s house; fewer openings in the school; etc.). Those high in RWA may equally dislike the outgroup member moving into the neighborhood but for different reasons. Here, it’s because this outgroup member brings in values or beliefs that the person high in RWA disagrees with, thus “threatening” the collective values of his or her group. RWA respects group unity over individual preferences, wanting to maintain group values in the face of differing opinions. Despite its name, though, RWA is not necessarily limited to people on the right (conservatives). Like SDO, there does appear to be an association between this personality scale (i.e. the preference for order, clarity, and conventional values) and conservative beliefs. However, regardless of political ideology, RWA focuses on groups’ competing frameworks of values. Extreme scores on RWA predict biases against outgroups while demanding in-group loyalty and conformity Notably, the combination of high RWA and high SDO predicts joining hate groups that openly endorse aggression against minority groups, immigrants, homosexuals, and believers in non-dominant religions (Altemeyer, 2004).

20th Century Biases: Subtle but Significant

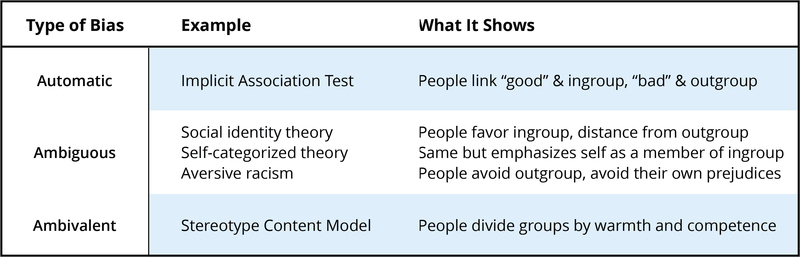

Fortunately, old-fashioned biases have diminished over the 20th century and into the 21st century. Openly expressing prejudice is like blowing second-hand cigarette smoke in someone’s face: It’s just not done any more in most circles, and if it is, people are readily criticized for their behavior. Still, these biases exist in people; they’re just less in view than before. These subtle biases are unexamined and sometimes unconscious but real in their consequences. They are automatic, ambiguous, and ambivalent, but nonetheless biased, unfair, and disrespectful to the belief in equality.

Automatic Biases

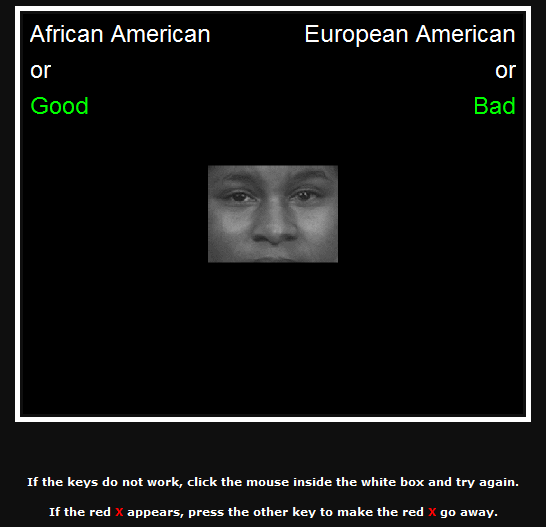

An actual screenshot from an IAT (Implicit Association Test) that is designed to test a person’s reaction time (measured in milliseconds) to an array of stimuli that are presented on the screen. This particular item is testing an individual’s unconscious reaction towards members of various ethnic groups. [Image: Courtesy of Anthony Greenwald from Project Implicit]

Most people like themselves well enough, and most people identify themselves as members of certain groups but not others. Logic suggests, then, that because we like ourselves, we therefore like the groups we associate with more, whether those groups are our hometown, school, religion, gender, or ethnicity. Liking yourself and your groups is human nature. The larger issue, however, is that own-group preference often results in liking other groups less. And whether you recognize this “favoritism” as wrong, this trade-off is relatively automatic, that is, unintended, immediate, and irresistible.

Social psychologists have developed several ways to measure this relatively automatic own-group preference, the most famous being the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald, Banaji, Rudman, Farnham, Nosek, & Mellott, 2002; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998). The test itself is rather simple and you can experience it yourself if you Google “implicit” or go to understandingprejudice.org. Essentially, the IAT is done on the computer and measures how quickly you can sort words or pictures into different categories. For example, if you were asked to categorize “ice cream” as good or bad, you would quickly categorize it as good. However, imagine if every time you ate ice cream, you got a brain freeze. When it comes time to categorize ice cream as good or bad, you may still categorize it as “good,” but you will likely be a little slower in doing so compared to someone who has nothing but positive thoughts about ice cream. Related to group biases, people may explicitly claim they don’t discriminate against outgroups—and this is very likely true. However, when they’re given this computer task to categorize people from these outgroups, that automatic or unconscious hesitation (a result of having mixed evaluations about the outgroup) will show up in the test. And as countless studies have revealed, people are mostly faster at pairing their own group with good categories, compared to pairing others’ groups. In fact, this finding generally holds regardless if one’s group is measured according to race, age, religion, nationality, and even temporary, insignificant memberships.

This all-too-human tendency would remain a mere interesting discovery except that people’s reaction time on the IAT predicts actual feelings about individuals from other groups, decisions about them, and behavior toward them, especially nonverbal behavior (Greenwald, Poehlman, Uhlmann, & Banaji, 2009). For example, although a job interviewer may not be “blatantly biased,” his or her “automatic or implicit biases” may result in unconsciously acting distant and indifferent, which can have devastating effects on the hopeful interviewee’s ability to perform well (Word, Zanna, & Cooper, 1973). Although this is unfair, sometimes the automatic associations—often driven by society’s stereotypes—trump our own, explicit values (Devine, 1989). And sadly, this can result in consequential discrimination, such as allocating fewer resources to disliked outgroups (Rudman & Ashmore, 2009). See Table 2 for a summary of this section and the next two sections on subtle biases.

Table 2: Subtle Biases

Ambiguous Biases

As the IAT indicates, people’s biases often stem from the spontaneous tendency to favor their own, at the expense of the other. Social identity theory (Tajfel, Billig, Bundy, & Flament, 1971) describes this tendency to favor one’s own in-group over another’s outgroup. And as a result, outgroup disliking stems from this in-group liking (Brewer & Brown, 1998). For example, if two classes of children want to play on the same soccer field, the classes will come to dislike each other not because of any real, objectionable traits about the other group. The dislike originates from each class’s favoritism toward itself and the fact that only one group can play on the soccer field at a time. With this preferential perspective for one’s own group, people are not punishing the other one so much as neglecting it in favor of their own. However, to justify this preferential treatment, people will often exaggerate the differences between their in-group and the outgroup. In turn, people see the outgroup as more similar in personality than they are. This results in the perception that “they” really differ from us, and “they” are all alike. Spontaneously, people categorize people into groups just as we categorize furniture or food into one type or another. The difference is that we people inhabit categories ourselves, as self-categorization theory points out (Turner, 1975). Because the attributes of group categories can be either good or bad, we tend to favor the groups with people like us and incidentally disfavor the others. In-group favoritism is an ambiguous form of bias because it disfavors the outgroup by exclusion. For example, if a politician has to decide between funding one program or another, s/he may be more likely to give resources to the group that more closely represents his in-group. And this life-changing decision stems from the simple, natural human tendency to be more comfortable with people like yourself.

A specific case of comfort with the ingroup is called aversive racism, so-called because people do not like to admit their own racial biases to themselves or others (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2010). Tensions between, say, a White person’s own good intentions and discomfort with the perhaps novel situation of interacting closely with a Black person may cause the White person to feel uneasy, behave stiffly, or be distracted. As a result, the White person may give a good excuse to avoid the situation altogether and prevent any awkwardness that could have come from it. However, such a reaction will be ambiguous to both parties and hard to interpret. That is, was the White person right to avoid the situation so that neither person would feel uncomfortable? Indicators of aversive racism correlate with discriminatory behavior, despite being the ambiguous result of good intentions gone bad.

Bias Can Be Complicated – Ambivalent Biases

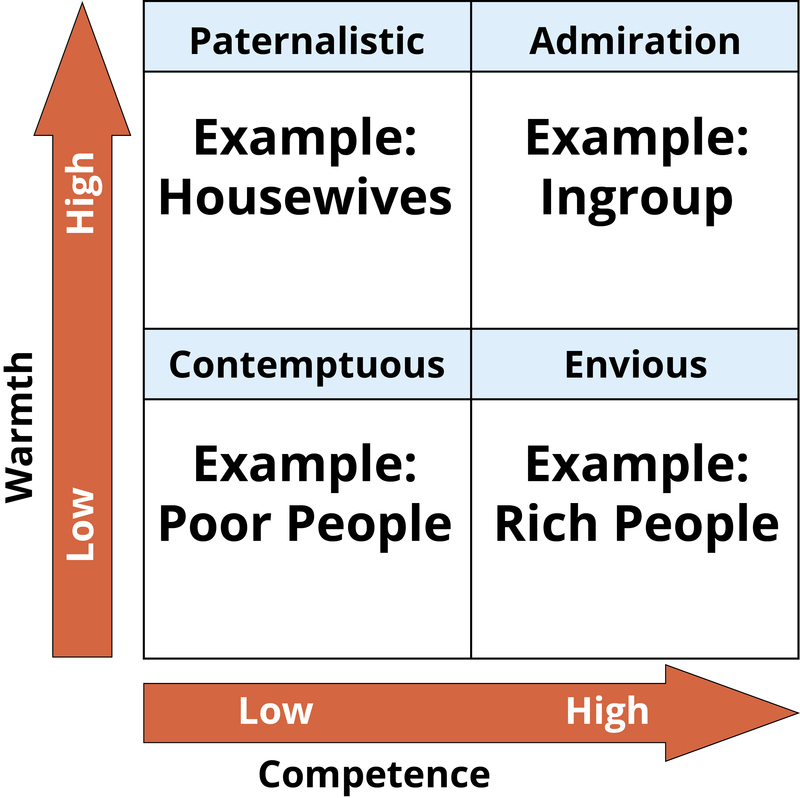

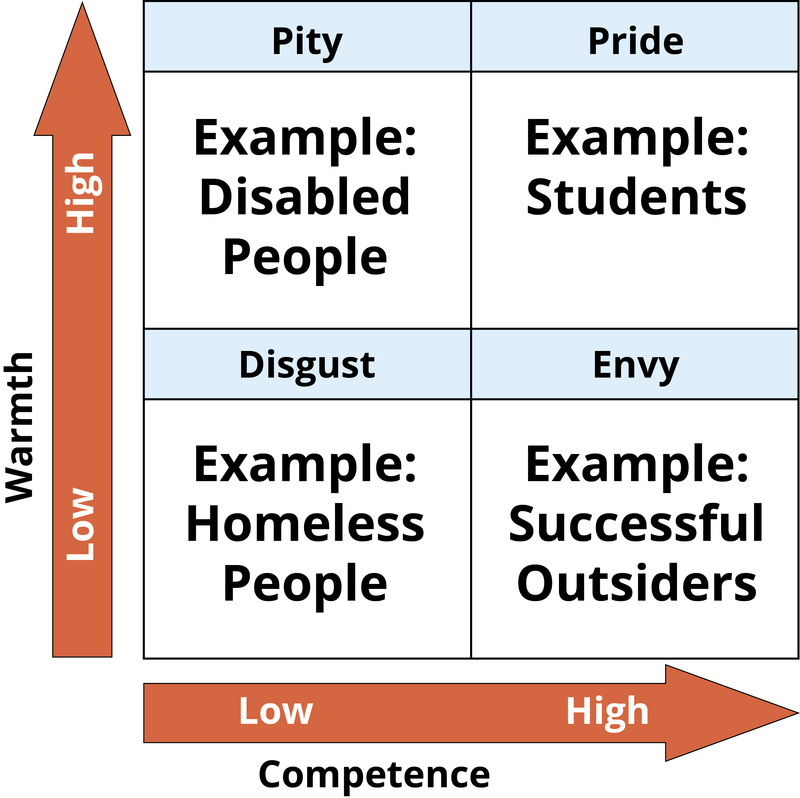

Not all stereotypes of outgroups are all bad. For example, ethnic Asians living in the United States are commonly referred to as the “model minority” because of their perceived success in areas such as education, income, and social stability. Another example includes people who feel benevolent toward traditional women but hostile toward nontraditional women. Or even ageist people who feel respect toward older adults but, at the same time, worry about the burden they place on public welfare programs. A simple way to understand these mixed feelings, across a variety of groups, results from the Stereotype Content Model (Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2007).

When people learn about a new group, they first want to know if its intentions of the people in this group are for good or ill. Like the guard at night: “Who goes there, friend or foe?” If the other group has good, cooperative intentions, we view them as warm and trustworthy and often consider them part of “our side.” However, if the other group is cold and competitive or full of exploiters, we often view them as a threat and treat them accordingly. After learning the group’s intentions, though, we also want to know whether they are competent enough to act on them (if they are incompetent, or unable, their intentions matter less). These two simple dimensions—warmth and competence—together map how groups relate to each other in society.

Figure 1: Stereotype Content Model – 4 kinds of stereotypes that form from perceptions of competence and warmth

There are common stereotypes of people from all sorts of categories and occupations that lead them to be classified along these two dimensions. For example, a stereotypical “housewife” would be seen as high in warmth but lower in competence. This is not to suggest that actual housewives are not competent, of course, but that they are not widely admired for their competence in the same way as scientific pioneers, trendsetters, or captains of industry. At another end of the spectrum are homeless people and drug addicts, stereotyped as not having good intentions (perhaps exploitative for not trying to play by the rules), and likewise being incompetent (unable) to do anything useful. These groups reportedly make society more disgusted than any other groups do.

Some group stereotypes are mixed, high on one dimension and low on the other. Groups stereotyped as competent but not warm, for example, include rich people and outsiders good at business. These groups that are seen as “competent but cold” make people feel some envy, admitting that these others may have some talent but resenting them for not being “people like us.” The “model minority” stereotype mentioned earlier includes people with this excessive competence but deficient sociability.

The other mixed combination is high warmth but low competence. Groups who fit this combination include older people and disabled people. Others report pitying them, but only so long as they stay in their place. In an effort to combat this negative stereotype, disability- and elderly-rights activists try to eliminate that pity, hopefully gaining respect in the process.

Altogether, these four kinds of stereotypes and their associated emotional prejudices (pride, disgust, envy, pity) occur all over the world for each of society’s own groups. These maps of the group terrain predict specific types of discrimination for specific kinds of groups, underlining how bias is not exactly equal opportunity.

Figure 2: Combinations of perceived warmth and confidence and the associated behaviors/emotional prejudices.

End-of-Chapter Summary: 21st Century Prejudices

As the world becomes more interconnected—more collaborations between countries, more intermarrying between different groups—more and more people are encountering greater diversity of others in everyday life. Just ask yourself if you’ve ever been asked, “What are you?” Such a question would be preposterous if you were only surrounded by members of your own group. Categories, then, are becoming more and more uncertain, unclear, volatile, and complex (Bodenhausen & Peery, 2009). People’s identities are multifaceted, intersecting across gender, race, class, age, region, and more. Identities are not so simple, but maybe as the 21st century unfurls, we will recognize each other by the content of our character instead of the cover on our outside.

References

Altemeyer, B. (2004). Highly dominating, highly authoritarian personalities. The Journal of Social Psychology, 144(4), 421-447. doi:10.3200/SOCP.144.4.421-448

Altemeyer, B. (1988). Enemies of freedom: Understanding right-wing authoritarianism. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bodenhausen, G. V., & Peery, D. (2009). Social categorization and stereotyping in vivo: The VUCA challenge. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(2), 133-151. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00167.x

Brewer, M. B., & Brown, R. J. (1998). Intergroup relations. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology, Vols. 1 and 2 (4th ed.) (pp. 554-594). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5-18. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5

Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2010). Intergroup bias. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology, Vol. 2 (5th ed.) (pp. 1084-1121). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Fiske, S. T. (1998). Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology, Vols. 1 and 2 (4th ed.) (pp. 357-411). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77-83. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., Rudman, L. A., Farnham, S. D., Nosek, B. A., & Mellott, D. S. (2002). A unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept. Psychological Review, 109(1), 3-25. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.1.3

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464-1480. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

Greenwald, A. G., Poehlman, T. A., Uhlmann, E. L., & Banaji, M. R. (2009). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 17-41. doi:10.1037/a0015575

Katz, D., & Braly, K. (1933). Racial stereotypes of one hundred college students. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 28(3), 280-290. doi:10.1037/h0074049

Rudman, L. A., & Ashmore, R. D. (2007). Discrimination and the implicit association test. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10(3), 359-372. doi:10.1177/1368430207078696

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149-178. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

Turner, J. C. (1975). Social comparison and social identity: Some prospects for intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 5(1), 5-34. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420050102

Word, C. O., Zanna, M. P., & Cooper, J. (1974). The nonverbal mediation of self-fulfilling prophecies in interracial interaction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10(2), 109-120. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(74)90059-6.

Attribution

Adapted from Prejudice, Discrimination, and Stereotyping by Susan T. Fiske under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

9.2 Dimension of Racial and Ethnic Equality

Learning Objectives

- Describe any two manifestations of racial and ethnic inequality in the United States.

- Explain how and why racial inequality takes a hidden toll on people of color.

- Provide two examples of white privilege.

Racial and ethnic inequality manifests itself in all walks of life. The individual and institutional discrimination just discussed is one manifestation of this inequality. We can also see stark evidence of racial and ethnic inequality in various government statistics. Sometimes statistics lie, and sometimes they provide all too true a picture; statistics on racial and ethnic inequality fall into the latter category. Table 3.2 “Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States” presents data on racial and ethnic differences in income, education, and health.

Table 3.2 Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States

| White | African American | Latino | Asian | Native American | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median family income, 2010 ($) | 68,818 | 39,900 | 41,102 | 76,736 | 39,664 |

| Persons who are college-educated, 2010 (%) | 30.3 | 19.8 | 13.9 | 52.4 | 14.9 (2008) |

| Persons in poverty, 2010 (%) | 9.9 (non-Latino) | 27.4 | 26.6 | 12.1 | 28.4 |

| Infant mortality (number of infant deaths per 1,000 births), 2006 | 5.6 | 12.9 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 8.3 |

Sources: Data from US Census Bureau. (2012). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2012. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2011/compendia/statab/131ed.html; US Census Bureau. (2012). American FactFinder. Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml; MacDorman, M., & Mathews, T. J. (2011). Infant Deaths—United States, 2000–2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(1), 49–51.

Asian Americans have higher family incomes than whites on average. Although Asian Americans are often viewed as a “model minority,” some Asians have been less able than others to achieve economic success, and stereotypes of Asians and discrimination against them remain serious problems. LindaDee2006 – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The picture presented by Table 3.2 “Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States” is clear: US racial and ethnic groups differ dramatically in their life chances. Compared to whites, for example, African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans have much lower family incomes and much higher rates of poverty; they are also much less likely to have college degrees. In addition, African Americans and Native Americans have much higher infant mortality rates than whites: Black infants, for example, are more than twice as likely as white infants to die. Later chapters in this book will continue to highlight various dimensions of racial and ethnic inequality.

Although Table 3.2 “Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States” shows that African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans fare much worse than whites, it presents a more complex pattern for Asian Americans. Compared to whites, Asian Americans have higher family incomes and are more likely to hold college degrees, but they also have a higher poverty rate. Thus many Asian Americans do relatively well, while others fare relatively worse, as just noted. Although Asian Americans are often viewed as a “model minority,” meaning that they have achieved economic success despite not being white, some Asians have been less able than others to climb the economic ladder. Moreover, stereotypes of Asian Americans and discrimination against them remain serious problems (Chou & Feagin, 2008). Even the overall success rate of Asian Americans obscures the fact that their occupations and incomes are often lower than would be expected from their educational attainment. They thus have to work harder for their success than whites do (Hurh & Kim, 1999).

The Increasing Racial/Ethnic Wealth Gap

At the beginning of this chapter, we noted that racial and ethnic inequality has existed since the beginning of the United States. We also noted that social scientists have warned that certain conditions have actually worsened for people of color since the 1960s (Hacker, 2003; Massey & Sampson, 2009).

Recent evidence of this worsening appeared in a report by the Pew Research Center (2011). The report focused on racial disparities in wealth, which includes a family’s total assets (income, savings, and investments, home equity, etc.) and debts (mortgage, credit cards, etc.). The report found that the wealth gap between white households on the one hand and African American and Latino households, on the other hand, was much wider than just a few years earlier, thanks to the faltering US economy since 2008 that affected blacks more severely than whites.

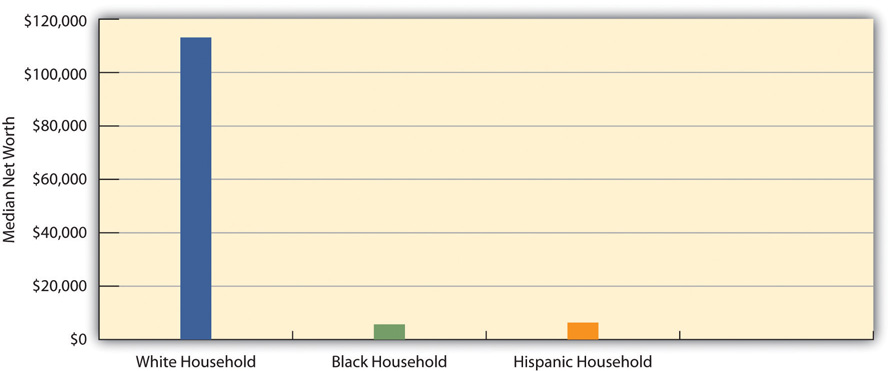

According to the report, whites’ median wealth was ten times greater than blacks’ median wealth in 2007, a discouraging disparity for anyone who believes in racial equality. By 2009, however, whites’ median wealth had jumped to twenty times greater than blacks’ median wealth and eighteen times greater than Latinos’ median wealth. White households had a median net worth of about $113,000, while black and Latino households had a median net worth of only $5,700 and $6,300, respectively (see Figure 3.5 “The Racial/Ethnic Wealth Gap (Median Net Worth of Households in 2009)”). This racial and ethnic difference is the largest since the government began tracking wealth more than a quarter-century ago.

Figure 3.5 The Racial/Ethnic Wealth Gap (Median Net Worth of Households in 2009)

Source: Pew Research Center, 2011.

A large racial/ethnic gap also existed in the percentage of families with negative net worth—that is, those whose debts exceed their assets. One-third of black and Latino households had negative net worth, compared to only 15 percent of white households. Black and Latino households were thus more than twice as likely as white households to be in debt.

The Hidden Toll of Racial and Ethnic Inequality

An increasing amount of evidence suggests that being black in a society filled with racial prejudice, discrimination, and inequality takes what has been called a “hidden toll” on the lives of African Americans (Blitstein, 2009). As we shall see in later chapters, African Americans on the average have worse health than whites and die at younger ages. In fact, every year there are an additional 100,000 African American deaths than would be expected if they lived as long as whites do. Although many reasons probably explain all these disparities, scholars are increasingly concluding that the stress of being black is a major factor (Geronimus et al., 2010).

In this way of thinking, African Americans are much more likely than whites to be poor, to live in high-crime neighborhoods, and to live in crowded conditions, among many other problems. As this chapter discussed earlier, they are also more likely, whether or not they are poor, to experience racial slights, refusals to be interviewed for jobs, and other forms of discrimination in their everyday lives. All these problems mean that African Americans from their earliest ages grow up with a great deal of stress, far more than what most whites experience. This stress, in turn, has certain neural and physiological effects, including hypertension (high blood pressure), that impair African Americans’ short-term and long-term health and that ultimately shorten their lives. These effects accumulate over time: black and white hypertension rates are equal for people in their twenties, but the black rate becomes much higher by the time people reach their forties and fifties. As a recent news article on evidence of this “hidden toll” summarized this process, “The long-term stress of living in a white-dominated society ‘weathers’ blacks, making them age faster than their white counterparts” (Blitstein, 2009, p. 48).

Although there is less research on other people of color, many Latinos and Native Americans also experience the various sources of stress that African Americans experience. To the extent this is true, racial and ethnic inequality also takes a hidden toll on members of these two groups. They, too, experience racial slights, live under disadvantaged conditions, and face other problems that result in high levels of stress and shorten their life spans.

White Privilege: The Benefits of Being White

American whites enjoy certain privileges merely because they are white. For example, they usually do not have to fear that a police officer will stop them simply because they are white, and they also generally do not have to worry about being mistaken for a bellhop, parking valet, or maid. Loren Kerns – Day 73 – CC BY 2.0.

Before we leave this section, it is important to discuss the advantages that US whites enjoy in their daily lives simply because they are white. Social scientists term these advantages white privilege and say that whites benefit from being white whether or not they are aware of their advantages (McIntosh, 2007).

This chapter’s discussion of the problems facing people of color points to some of these advantages. For example, whites can usually drive a car at night or walk down a street without having to fear that a police officer will stop them simply because they are white. Recalling the Trayvon Martin tragedy, they can also walk down a street without having to fear they will be confronted and possibly killed by a neighborhood watch volunteer. In addition, whites can count on being able to move into any neighborhood they desire to as long as they can afford the rent or mortgage. They generally do not have to fear being passed up for promotion simply because of their race. White students can live in college dorms without having to worry that racial slurs will be directed their way. White people, in general, do not have to worry about being the victims of hate crimes based on their race. They can be seated in a restaurant without having to worry that they will be served more slowly or not at all because of their skin color. If they are in a hotel, they do not have to think that someone will mistake them for a bellhop, parking valet, or maid. If they are trying to hail a taxi, they do not have to worry about the taxi driver ignoring them because the driver fears he or she will be robbed.

Social scientist Robert W. Terry (1981, p. 120) once summarized white privilege as follows: “To be white in America is not to have to think about it. Except for hard-core racial supremacists, the meaning of being white is having the choice of attending to or ignoring one’s own whiteness” (emphasis in original). For people of color in the United States, it is not an exaggeration to say that race and ethnicity is a daily fact of their existence. Yet whites do not generally have to think about being white. As all of us go about our daily lives, this basic difference is one of the most important manifestations of racial and ethnic inequality in the United States.

Perhaps because whites do not have to think about being white, many studies find they tend to underestimate the degree of racial inequality in the United States by assuming that African Americans and Latinos are much better off than they really are. As one report summarized these studies’ overall conclusion, “Whites tend to have a relatively rosy impression of what it means to be a black person in America. Whites are more than twice as likely as blacks to believe that the position of African Americans has improved a great deal” (Vedantam, 2008, p. A3). Because whites think African Americans and Latinos fare much better than they really do, that perception probably reduces whites’ sympathy for programs designed to reduce racial and ethnic inequality.

Key Takeaways

- Compared to non-Latino whites, people of color have lower incomes, lower educational attainment, higher poverty rates, and worse health.

- Racial and ethnic inequality takes a hidden toll on people of color, as the stress they experience impairs their health and ability to achieve.

- Whites benefit from being white, whether or not they realize it. This benefit is called white privilege.

For Your Review

-

Write a brief essay that describes important dimensions of racial and ethnic inequality in the United States.

-

If you are white, describe a time when you benefited from white privilege, whether or not you realized it at the time. If you are a person of color, describe an experience when you would have benefited if you had been white.

References

Blitstein, R. (2009). Weathering the storm. Miller-McCune, 2(July–August), 48–57.

Chou, R. S., & Feagin, J. R. (2008). The myth of the model minority: Asian Americans facing racism. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Pearson, J., Seashols, S., Brown, K., & Cruz., T. D. (2010). Do US black women experience stress-related accelerated biological aging? Human Nature: An Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective, 21, 19–38.

Hacker, A. (2003). Two nations: Black and white, separate, hostile, unequal (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Scribner.

Hurh, W. M., & Kim, K. C. (1999). The “success” image of Asian Americans: Its validity, and its practical and theoretical implications. In C. G. Ellison & W. A. Martin (Eds.), Race and ethnic relations in the United States (pp. 115–122). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Massey, D. S., & Sampson, R. J. (2009). Moynihan redux: Legacies and lessons. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621, 6–27.

McIntosh, P. (2007). White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondence through work in women’s studies. In M. L. Andersen & P. H. Collins (Eds.), Race, class, and gender: An anthology (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Pew Research Center. (2011). Twenty-to-one: Wealth gaps rise to record highs between whites, blacks and Hispanics. Washington, DC: Author.

Terry, R. W. (1981). The negative impact on white values. In B. P. Bowser & R. G. Hunt (Eds.), Impacts of racism on white Americans (pp. 119–151). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Vedantam, S. (2008, March 24). Unequal perspectives on racial equality. The Washington Post, p. A3.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 3.2, Social Problems by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

9.3 Feminism and Sexism

Learning Objectives

- Define feminism, sexism, and patriarchy.

- Discuss evidence for a decline in sexism.

In the national General Social Survey (GSS), slightly more than one-third of the public agrees with this statement: “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” Do you agree or disagree with this statement? If you are like the majority of college students, you disagree.

Today a lot of women, and some men, will say, “I’m not a feminist, but…,” and then go on to add that they hold certain beliefs about women’s equality and traditional gender roles that actually fall into a feminist framework. Their reluctance to self-identify as feminists underscores the negative image that feminists and feminism have but also suggests that the actual meaning of feminism may be unclear.

Feminism and sexism are generally two sides of the same coin. Feminism refers to the belief that women and men should have equal opportunities in economic, political, and social life, while sexism refers to a belief in traditional gender role stereotypes and in the inherent inequality between men and women. Sexism thus parallels the concept of racial and ethnic prejudice discussed in Chapter 3 “Racial and Ethnic Inequality”. Women and people of color are both said, for biological and/or cultural reasons, to lack certain qualities for success in today’s world.

Feminism as a social movement began in the United States during the abolitionist period before the Civil War. Elizabeth Cady Stanton (left) and Lucretia Mott (right) were outspoken abolitionists who made connections between slavery and the oppression of women.

The US Library of Congress – public domain; The US Library of Congress – public domain.

Two feminist movements in US history have greatly advanced the cause of women’s equality and changed views about gender. The first began during the abolitionist period, when abolitionists such as Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton began to see similarities between slavery and the oppression of women. This new women’s movement focused on many issues but especially the right to vote, which women won in 1920. The second major feminist movement began in the late 1960s, as women active in the Southern civil rights movement turned their attention to women’s rights, and it is still active today. This movement has profoundly changed public thinking and social and economic institutions, but, as we will soon see, much gender inequality remains.

Several varieties of feminism exist. Although they all share the basic idea that women and men should be equal in their opportunities in all spheres of life, they differ in other ways (Hannam, 2012). Liberal feminism believes that the equality of women can be achieved within our existing society by passing laws and reforming social, economic, and political institutions. In contrast, socialist feminism blames capitalism for women’s inequality and says that true gender equality can result only if fundamental changes in social institutions, and even a socialist revolution, are achieved. Radical feminism, on the other hand, says that patriarchy (male domination) lies at the root of women’s oppression and that women are oppressed even in noncapitalist societies. Patriarchy itself must be abolished, they say, if women are to become equal to men. Finally, multicultural feminism emphasizes that women of color are oppressed not only because of their gender but also because of their race and class. They thus face a triple burden that goes beyond their gender. By focusing their attention on women of color in the United States and other nations, multicultural feminists remind us that the lives of these women differ in many ways from those of the middle-class women who historically have led US feminist movements.

The Growth of Feminism and the Decline of Sexism

What evidence is there for the impact of the contemporary women’s movement on public thinking? The GSS, the Gallup poll, and other national surveys show that the public has moved away from traditional views of gender toward more modern ones. Another way of saying this is that the public has moved from sexism toward feminism.

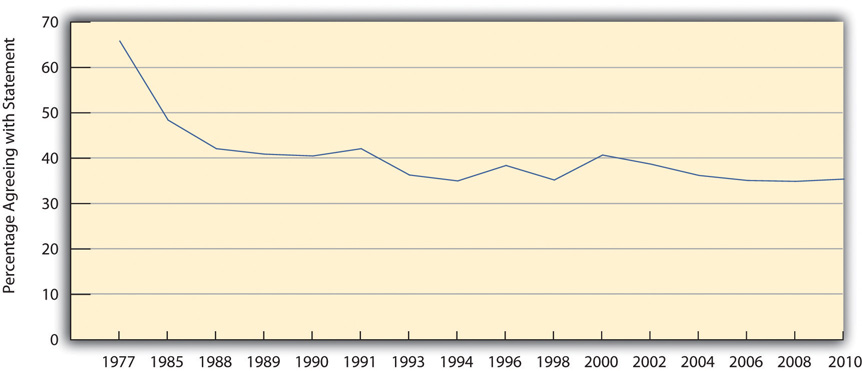

To illustrate this, let’s return to the GSS statement that it is much better for the man to achieve outside the home and for the woman to take care of home and family. Figure 4.2 “Change in Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family, 1977–2010” shows that agreement with this statement dropped sharply during the 1970s and 1980s before leveling off afterward to slightly more than one-third of the public.

Figure 4.2 Change in Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family, 1977–2010

Percentage agreeing that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.”

Source: Data from General Social Surveys. (1977–2010). Retrieved from http://sda.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/hsda?harcsda+gss10.

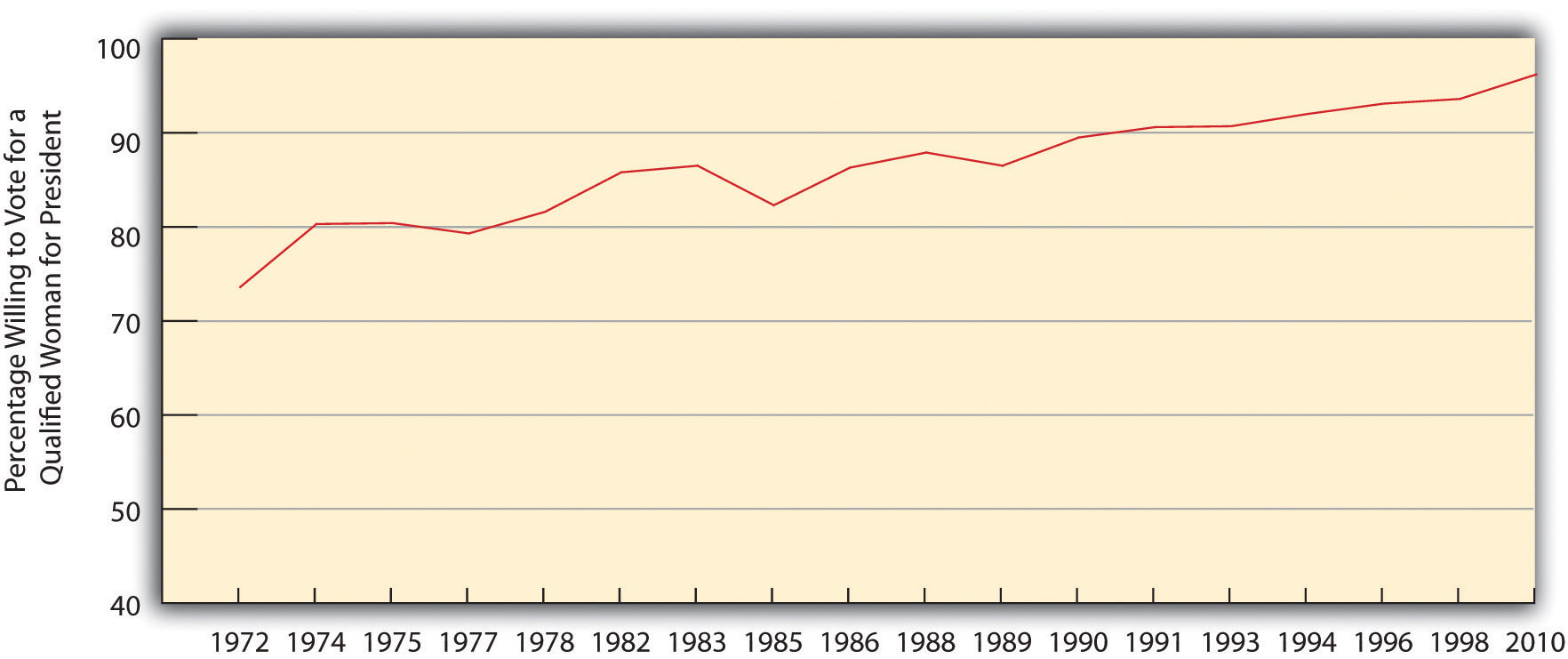

Another GSS question over the years has asked whether respondents would be willing to vote for a qualified woman for president of the United States. As Figure 4.3 “Change in Willingness to Vote for a Qualified Woman for President” illustrates, this percentage rose from 74 percent in the early 1970s to a high of 96.2 percent in 2010. Although we have not yet had a woman president, despite Hillary Rodham Clinton’s historic presidential primary campaign in 2007 and 2008 and Sarah Palin’s presence on the Republican ticket in 2008, the survey evidence indicates the public is willing to vote for one. As demonstrated by the responses to the survey questions on women’s home roles and on a woman president, traditional gender views have indeed declined.

Figure 4.3 Change in Willingness to Vote for a Qualified Woman for President

Source: Data from General Social Survey. (2010). Retrieved from http://sda.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/hsda?harcsda+gss10.

Key Takeaways

- Feminism refers to the belief that women and men should have equal opportunities in economic, political, and social life, while sexism refers to a belief in traditional gender role stereotypes and in the inherent inequality between men and women.

- Sexist beliefs have declined in the United States since the early 1970s.

For Your Review

- Do you consider yourself a feminist? Why or why not?

- Think about one of your parents or of another adult much older than you. Does this person hold more traditional views about gender than you do? Explain your answer.

References

Hannam, J. (2012). Feminism. New York, NY: Pearson Longman.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 4.2, Social Problems by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

9.4 Reducing Gender Inequality

Learning Objectives

- Describe any three policies or programs that should help reduce gender inequality.

- Discuss possible ways of reducing rape and sexual assault.

Gender inequality is found in varying degrees in most societies around the world, and the United States is no exception. Just as racial/ethnic stereotyping and prejudice underlie racial/ethnic inequality (see Chapter 3 “Racial and Ethnic Inequality”), so do stereotypes and false beliefs underlie gender inequality. Although these stereotypes and beliefs have weakened considerably since the 1970s thanks in large part to the contemporary women’s movement, they obviously persist and hamper efforts to achieve full gender equality.

A sociological perspective reminds us that gender inequality stems from a complex mixture of cultural and structural factors that must be addressed if gender inequality is to be reduced further than it already has been since the 1970s. Despite changes during this period, children are still socialized from birth into traditional notions of femininity and masculinity, and gender-based stereotyping incorporating these notions still continues. Although people should certainly be free to pursue whatever family and career responsibilities they desire, socialization and stereotyping still combine to limit the ability of girls and boys and women and men alike to imagine less traditional possibilities. Meanwhile, structural obstacles in the workplace and elsewhere continue to keep women in a subordinate social and economic status relative to men.

To reduce gender inequality, then, a sociological perspective suggests various policies and measures to address the cultural and structural factors that help produce gender inequality. These steps might include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Reduce socialization by parents and other adults of girls and boys into traditional gender roles.

- Confront gender stereotyping by the popular and news media.

- Increase public consciousness of the reasons for, extent of, and consequences of rape and sexual assault, sexual harassment, and pornography.

- Increase enforcement of existing laws against gender-based employment discrimination and against sexual harassment.

- Increase funding of rape-crisis centers and other services for girls and women who have been raped and/or sexually assaulted.

- Increase government funding of high-quality day-care options to enable parents, and especially mothers, to work outside the home if they so desire, and to do so without fear that their finances or their children’s well-being will be compromised.

- Increase mentorship and other efforts to boost the number of women in traditionally male occupations and in positions of political leadership.

As we consider how best to reduce gender inequality, the impact of the contemporary women’s movement must be neither forgotten nor underestimated. Since it began in the late 1960s, the women’s movement has generated important advances for women in almost every sphere of life. Brave women (and some men) challenged the status quo by calling attention to gender inequality in the workplace, education, and elsewhere, and they brought rape and sexual assault, sexual harassment, and domestic violence into the national consciousness. For gender inequality to continue to be reduced, it is essential that a strong women’s movement continue to remind us of the sexism that still persists in American society and the rest of the world.

Reducing Rape and Sexual Assault

As we have seen, gender inequality also manifests itself in the form of violence against women. A sociological perspective tells us that cultural myths and economic and gender inequality help lead to rape, and that the rape problem goes far beyond a few psychopathic men who rape women. A sociological perspective thus tells us that our society cannot just stop at doing something about these men. Instead it must make more far-reaching changes by changing people’s beliefs about rape and by making every effort to reduce poverty and to empower women. This last task is especially important, for, as Randall and Haskell (1995, p. 22) observed, a sociological perspective on rape “means calling into question the organization of sexual inequality in our society.”

Aside from this fundamental change, other remedies, such as additional and better funded rape-crisis centers, would help women who experience rape and sexual assault. Yet even here women of color face an additional barrier. Because the antirape movement was begun by white, middle-class feminists, the rape-crisis centers they founded tended to be near where they live, such as college campuses, and not in the areas where women of color live, such as inner cities and Native American reservations. This meant that women of color who experienced sexual violence lacked the kinds of help available to their white, middle-class counterparts (Matthews, 1989), and despite some progress, this is still true today.

Key Takeaways

- Certain government efforts, including increased financial support for child care, should help reduce gender inequality.

- If gender inequality lessens, rape and sexual assault should decrease as well.

For Your Review

- To reduce gender inequality, do you think efforts should focus more on changing socialization practices or on changing policies in the workplace and schools? Explain your answer.

- How hopeful are you that rape and sexual assault will decrease significantly in your lifetime?

References

Matthews, N. A. (1989). Surmounting a legacy: The expansion of racial diversity in a local anti-rape movement. Gender & Society, 3, 518–532.

Randall, M., & Haskell, L. (1995). Sexual violence in women’s lives: Findings from the women’s safety project, a community-based survey. Violence Against Women, 1, 6–31.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 4.6, Social Problems by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

9.5 The Benefits and Costs of Being Male

Learning Objectives

- List some of the benefits of being male.

- List some of the costs of being male.

Most of the discussion so far has been about women, and with good reason: In a sexist society such as our own, women are the subordinate, unequal sex. But gender means more than female, and a few comments about men are in order.

Benefits

We have already discussed gender differences in occupations and incomes that favor men over women. In a patriarchal society, men have more wealth than women and more influence in the political and economic worlds more generally.

Men profit in other ways as well. In Chapter 3 “Racial and Ethnic Inequality”, we talked about white privilege, or the advantages that whites automatically have in a racist society whether or not they realize they have these advantages. Many scholars also talk about male privilege, or the advantages that males automatically have in a patriarchal society whether or not they realize they have these advantages (McIntosh, 2007).

A few examples illustrate male privilege. Men can usually walk anywhere they want or go into any bar they want without having to worry about being raped or sexually harassed. Susan Griffin was able to write “I have never been free of the fear of rape” because she was a woman; it is no exaggeration to say that few men could write the same thing and mean it. Although some men are sexually harassed, most men can work at any job they want without having to worry about sexual harassment. Men can walk down the street without having strangers make crude remarks about their looks, dress, and sexual behavior. Men can ride the subway system in large cities without having strangers grope them, flash them, or rub their bodies against them. Men can apply for most jobs without worrying about being rejected because of their gender, or, if hired, not being promoted because of their gender. We could go on with many other examples, but the fact remains that in a patriarchal society, men automatically have advantages just because they are men, even if race/ethnicity, social class, and sexual orientation affect the degree to which they are able to enjoy these advantages.

Costs

Yet it is also true that men pay a price for living in a patriarchy. Without trying to claim that men have it as bad as women, scholars are increasingly pointing to the problems men face in a society that promotes male domination and traditional standards of masculinity such as assertiveness, competitiveness, and toughness (Kimmel & Messner, 2010). Socialization into masculinity is thought to underlie many of the emotional problems men experience, which stem from a combination of their emotional inexpressiveness and reluctance to admit to, and seek help for, various personal problems (Wong & Rochlen, 2005). Sometimes these emotional problems build up and explode, as mass shootings by males at schools and elsewhere indicate, or express themselves in other ways. Compared to girls, for example, boys are much more likely to be diagnosed with emotional disorders, learning disabilities, and attention deficit disorder, and they are also more likely to commit suicide and to drop out of high school.

Men experience other problems that put themselves at a disadvantage compared to women. They commit much more violence than women do and, apart from rape and sexual assault, also suffer a much higher rate of violent victimization. They die earlier than women and are injured more often. Because men are less involved than women in child rearing, they also miss out on the joy of parenting that women are much more likely to experience.

Growing recognition of the problems males experience because of their socialization into masculinity has led to increased concern over what is happening to American boys. Citing the strong linkage between masculinity and violence, some writers urge parents to raise their sons differently in order to help our society reduce its violent behavior (Corbett, 2011). In all these respects, boys and men—and our nation as a whole—are paying a very real price for being male in a patriarchal society.

Key Takeaways

- In a patriarchal society, males automatically have certain advantages, including a general freedom from fear of being raped and sexually assaulted and from experiencing job discrimination on the basis of their gender.

- Men also suffer certain disadvantages from being male, including higher rates of injury, violence, and death and a lower likelihood of experiencing the joy that parenting often brings.

For Your Review

- What do you think is the most important advantage, privilege, or benefit that men enjoy in the United States? Explain your answer.

- What do you think is the most significant cost or disadvantage that men experience? Again, explain your answer.

References

Corbett, K. (2011). Boyhoods: Rethinking masculinities. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kimmel, M. S., & Messner, M. A. (Eds.). (2010). Men’s lives (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

McIntosh, P. (2007). White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondence through work in women’s studies. In M. L. Andersen & P. H. Collins (Eds.), Race, class, and gender: An anthology (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Wong, Y. J., & Rochlen, A. B. (2005). Demystifying men’s emotional behavior: New directions and implications for counseling and research. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6, 62–72.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapter 4.5, Social Problems by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

9.6 Masculinities

Another concept that troubles the gender binary is the idea of multiple masculinities (Connell, 2005). Connell suggests that there is more than one kind of masculinity and what is considered “masculine” differs by race, class, ethnicity, sexuality, and gender. For example, being knowledgeable about computers might be understood as masculine because it can help a person accumulate income and wealth, and we consider wealth to be masculine. However, computer knowledge only translates into “masculinity” for certain men. While an Asian-American, middle-class man might get a boost in “masculinity points” (as it were) for his high-paying job with computers, the same might not be true for a working-class white man whose white-collar desk job may be seen as a weakness to his masculinity by other working-class men. Expectations for masculinity differ by age; what it means to be a man at 19 is very different than what it means to be a man at 70. Therefore, masculinity intersects with other identities and expectations change accordingly.

Judith (Jack) Halberstam used the concept of female masculinity to describe the ways female-assigned people may accomplish masculinity (2005). Halberstam defines masculinity as the connection between maleness and power, which female-assigned people access through drag-king performances, butch identity (where female-assigned people appear and act masculine and may or may not identify as women), or trans identity. Separating masculinity from male-assigned bodies illustrates how performative it is, such that masculinity is accomplished in interactions and not ordained by nature.

Attribution

Adapted from Unit II, Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.