Chapter 30: Intimate Partner Violence Among Immigrants & Refugees

Learning Objectives

- Learn from the national and global perspective of intimate partner violence among immigrants and refugees.

- Recognizing that the world is constantly and rapidly changing.

- Recognizing that Global/national/international events can have an impact on individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities.

- Global implications dictate that we foster international relationships and opportunities to address international concerns, needs, problems, and actions to improve the well-being of not only U.S. citizens, but global citizens.

32.1 Introduction

Imagine that you, your partner, and your children are recently arrived in the United States. You do not speak the language well, and everything from the foods in grocery stores to the type of floor in your apartment feels new to you. While you and your family try to adjust to these changes, what kind of stresses would you be under? How would it affect your relationship with your partner?

Now imagine that in the midst of these stressors and changes, your partner periodically comes home and snaps. Your partner curses at you, grabs your shoulders, and throws you down on the ground. What do you do? Who in this new country can help you?

Approximately one out of every three women (36%) and one out of every four men (29%) in the United States report lifetime experiences of rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner (Black et al., 2011). Rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) are even higher among immigrants, ranging from 30% to 60% (Biafora & Warbeit, 2007; Erez, Adelman, & Gregory, 2009; Hazen & Soriano, 2005; Sabina, Cuevas, & Zadnik, 2014). There are likely additional incidents that go unreported when immigrant and refugee groups do not know how to access or navigate social and legal services in the United States, or when immigrants and refugees come from nations where violence against women is culturally accepted.

IPV has a significant impact on immigrant and refugee women and their families. Immigrant and refugee women who experience IPV are more likely to experience mental health issues and distress; for example, Latina immigrants who experience IPV are three times as likely to be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as Latina immigrants with no experiences of IPV (Fedovskiy, Higgins, & Paranjape, 2008). Also, children who witness IPV are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, PTSD, and aggression than children with no exposure to IPV (Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003; Wolfe, Crooks, Lee, & McIntyre-Smith, 2003). IPV can also be fatal. Studies show that immigrant women are more likely than United States-born women to die from IPV (Frye, Hosein, Waltermaurer, Blaney, & Wilt, 2005). IPV is particularly threatening for undocumented immigrants as their access to police and social services is limited and accusations of abuse in the presence of a child can lead to both deportation and alternative custody arrangements (Rogerson, 2012).

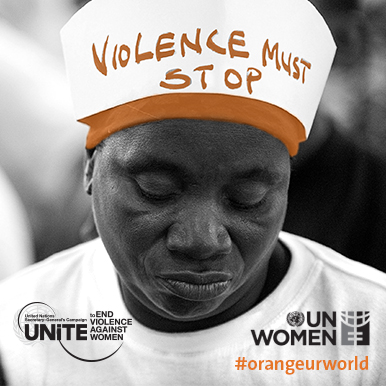

The UN has a campaign to end violence against women across the globe. For 2 weeks in 2013, activists and celebrities wore orange to raise awareness of violence against women.

UN Women – Orange Your World in 16 days – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a broad overview of IPV and its unique characteristics among immigrants. We will explore IPV-related risk and protective factors, and also discuss how survivors cope with IPV. Finally, we will suggest how future research and interventions might address IPV among immigrants and refugees.

Which term to use?

There is controversy over whether to call people who have experience IPV “victims” or “survivors.” In this chapter we use the word “survivor,” but there are good reasons to use both terms. To read a brief description of the reasons for using each term, visit: https://www.rainn.org/articles/key-terms-and-phrases.

Jaime Ballard (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota), Matthew Witham (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota), and Dr. Mona Mittal (School of Public Health, University of Maryland)

32.2 Defining IPV

It is impossible to form a universal definition of IPV that captures the sentiments of highly varied people groups. Immigrants, refugees, and United States-born citizens come from diverse cultures, ideologies, religions, and philosophies, each of which can impact perceptions of IPV. Even within the same culture or religion, family traditions and norms might greatly influence perceptions of IPV. Recognizing the different perspectives on IPV around the world will help to identify points of ideological tension in order to better understand the factors that initiate and sustain IPV in immigrant and refugee populations.

Cultural Variation in Perceptions of IPV

The World Health Organization (WHO), which is a United Nations recognized agency, defines IPV as “behavior by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviors” (2017). While WHO provides us with a standard definition of IPV, past and present contexts of different countries inform their IPV-focused laws and also shape individuals’ and families’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors regarding IPV. In each culture, different implicit and explicit messages are endorsed through social, political, religious, educational, and economic institutions. The following examples highlight the variance in IPV across countries. In each case, the legal definition of IPV is similar to the WHO definition (including physical, sexual, psychological abuse and controlling behaviors), but there is wide variation in the perceptions of IPV.

- In South Africa: Gender discrimination in a traditionally male-dominated society has promoted female objectification and discrimination. Women report not feeling permitted to stand up to or refuse male directives, which may reduce any attempts to interrupt violence or leave the relationship. This is further exacerbated by the fact that men typically hold financial control in the relationship. Approximately 50% of men physically abuse their partners (Jewkes, Levin, & Penn-Kekana, 2002).

- In Columbia: “Machismo” attitudes continue to exist. Patriarchal hegemony seems to reinforce tolerance for violent, neglectful actions of men, while more mild acts by women (i.e., not coming home on time) are considered abusive to men (Abramzon, 2004). A government survey found the majority (64%) of people reported that if they were faced with a case of IPV, they would encourage the partners to reconcile, and a large majority (81%) was unaware that there are laws against IPV (Segura, 2015).

- In Zimbabwe: The patriarchal framework of communities is linked to biblical texts that seem to support male oppressiveness. Zimbabwean women’s relationship behaviors are also shaped by their religious and cultural beliefs. A study by Makahamadze, Isacco, and Chireshe (2012) found that many women opposed legislation intended to reduce IPV because they believed it went against their religious teachings.

As seen in these examples, the cultural context informs how people and countries perceive and respond to IPV. It is important to be aware of the ways that national contexts and cultures can shape the interpretation and recognition of IPV.

Definition of IPV in the United States

The United States government promotes one understanding of IPV and expects those living within its borders to act in response to that understanding, albeit this view may not be shared by those from other countries-of-origin. There are four primary types of IPV as defined by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC; Breiding et al., 2015):

- Physical violence. This is “the intentional use of physical force with the potential for causing death, disability, injury, or harm” (Breiding et al., 2015, p. 11), including a wide range of aggressive acts (i.e., pushing, hitting, biting, and punching).

- Sexual violence. This includes both forcefully convincing a person into sexual acts against his/her wishes and any abusive sexual contact. Manipulating vulnerable individuals into sexual acts when they may lack the capacity to fully understand the nature of such acts is also termed sexual violence.

- Stalking. This includes “a pattern of repeated, unwanted, attention and contact that causes fear or concern of one’s safety or the safety of someone else” (e.g., the safety of a family member or close friend) (Breiding et al., 2015, p. 14).

- Psychological aggression. This includes the “use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to a) harm another person mentally or emotionally; and/or b) exerting control over someone” (Brieiding et al., 2015, p. 14-15).

A single episode of violence can include one type or all four types; these categories are not mutually exclusive. IPV can occur in a range of relationships including current spouses, current non-marital partners, former marital partners, and former non-marital partners.

Are you experiencing partner violence?

Please, seek help. Everyone deserves to be physically safe and respected in their relationships. You can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 800-799-SAFE (7233) or 800-787-3224 (TDD) any time of night or day. Staff speak many languages, and they can give you the phone numbers of local shelters and other resources.

32.3 IPV Among Immigrants & Refugees

Current literature on IPV in immigrant and refugee populations is mostly organized by either country- or by continent- of- origin. There is merit to this practice. There is merit to this practice. It allows for the possible identification of similarities and differences among individuals, couples, and families from comparable regional, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, there is ample evidence that perspectives of IPV are varied throughout the world (Malley-Morrison, 2004), and that separating the literature by these boundaries allows us to group people with potentially similar worldviews.

However, we will not be using geographical demarcations to organize our review of the literature. In our review, we will highlight shared experiences across groups of immigrants, and also note experiences that are markedly different. Both the shared and divergent experiences of individuals from similar and differing immigrant and refugee groups will be highlighted. We will pay close attention will be given to findings that expose atypical or unusual trends.

IPV has serious consequences for everyone; however, there are a few unique features of IPV among immigrants and refugees. Specifically, an abusive partner of an immigrant/refugee has additional methods of control compared to United States-born couples. The partner may limit contact with families in the country-of-origin or refuse to allow them to learn English (Raj & Silverman, 2002). Both of these methods cut off social support and access to tangible resources. Additionally, abusive partners may try to control undocumented partners by threats relating to their immigration status (Erez et al., 2009; Hass et al., 2000). They might threaten to report the partner or her children to immigration officials, refuse to file papers to obtain legal status, threaten to withdraw papers filed for legal status, or restrict access to documents needed to file for legal status.

32.4 Risk & Protective Factors

For immigrants/refugees and United States-born individuals alike, there are many factors that increase the risk of IPV. Individuals who have experienced abuse in childhood, either experiencing child abuse or witnessing IPV between parents, are more likely to experience IPV as adults (Simonelli, Mullis, Elliiot, & Pierce, 2002; Yoshioka et al., 2001). Experiencing trauma in adulthood increases risk of perpetration of IPV: men who have been exposed to political violence or imprisonment are twice as likely to perpetrate IPV as those who have not (Gupta, Acevedo-Garcia, & Hemenway, 2009; Shiu-Thornton, Senturia, & Sullivan, 2005). Additional risk factors for victimization and or perpetration include having high levels of stress, impulsivity, and alcohol or drug use by either partner (Brecklin, 2002; Dutton, Orloff, & Hass, 2000; Fife, Ebersole, Bigatti, Lane, & Huger, 2008; Hazen & Soriano, 2007; Kim-Goodwin, Maume, & Fox, 2014; Zarza, Ponsoda, & Carrillo, 2009). Social isolation, poverty, and neighborhood crime are also associated with increased risk (Koenig, Stephenson, Ahmen, Jejeeboy, & Campbell, 2006; Zarza et al., 2009).

In addition to these shared factors, there are many risk factors of experiencing IPV specific to immigrants, as well as a key protective factor. Each of these will be addressed in detail here.

Changes in Social Status During Resettlement

IPV is more likely to occur when an individual’s social status changes due to immigration (Lau, Takeuchi, & Alegria, 2006). During resettlement, many men lose previous occupational status and are no longer able to be the sole provider for their families. They may also experience a decrease in decision-making power relative to their partners. This kind of major change can lead to a loss of identity and purpose.

Shifts in social status are associated with greater risk of IPV. For example, in a study of Korean immigrant men, abuse toward wives was more common in families where the husband had greater difficulties adjusting to life in the United States (Rhee, 1997). In a study of Chinese immigrant men, those who felt they had lost power were more likely to have tolerant attitudes toward IPV (Jin & Keat, 2010).

Time in the United States and Acculturation

Greater time in the United States is associated with greater family conflict and IPV (Cook et al., 2009; Gupta, Acevedo-Garcia, Hemenway, Decker, Ray, & Silverman, 2010). Studies find that recent immigrants generally report lower IPV than individuals in the home country, United States-born citizens in the destination country, or immigrants who have been in the destination country for a long time (Hazen & Soriano, 2007; Gupta et al., 2010; Sabina et al., 2014). It may be that the process of immigration requires an intact family, and that families who can successfully migrate to the United States have strong coping and functionality skills (Sabina et al., 2014). However, over time, ongoing stresses contribute to an increase in IPV.

Studies have shown that when an individual has greater levels of acculturation to United States and greater experience of acculturation stress, they face greater conflict, IPV, and tolerance of IPV in their relationships (Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, Vaeth, & Harris, 2007; Garcia et al., 2005; Yoshihama, Blazevski, & Bybee, 2014). Acculturation is associated with less avoidance of conflict and more expression of feelings, which may partially explain why IPV would increase (Flores et al., 2004).

Although acculturation is associated with greater IPV, research has also demonstrated its protective effects. For example, one study found that women who are more acculturated practice more safety behaviors in the face of IPV (Nava, McFarlane, Gilroy, & Maddoux, 2014).

Norms from Country-of-Origin

Rigid, patriarchal gender roles learned in the country-of-origin are associated with increased tolerance for and experience of IPV (Morash, Bui, Zhang, & Holtfreter, 2007; Yoshioka, DiNoia, & Ullah, 2001). Arguments about fulfilling gender roles are also associated with greater IPV (Morash et al., 2007). For example, a study found that a quarter of their sample of Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Cambodian immigrants believed that IPV was justified in certain role-specific situations, such as in cases of sexual infidelity or refusal to perform housekeeping duties (Yoshioka et al., 2001).

Social Support: A Protective Factor

There are many other protective factors that reduce risk of IPV in many populations including education, parental monitoring for adolescent relationships, and couple conflict resolution strategies and satisfaction in adult couples (Canaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012). However, the limited research on immigrant and refugee communities has addressed only one protective factor: social support. Social support from family, friends, and community can protect against IPV in immigrants and refugees. For example, involvement in one’s own cultural community was associated with reduced IPV-supporting attitudes among East Asian immigrants (Yoshihama et al., 2014). However, there are exceptions. A study of 220 immigrant Southeast Asians found that those reporting more social support experienced more IPV than those reporting lower levels of social support (Wong, DiGangi, Young, Huang, Smith, & John, 2011). This may be due to social pressures within the community (see the “Barriers to Help Seeking” section).

32.5 Responses to IPV

Survivors of IPV are often not passive or helpless. They try a wide variety of tactics to try to prevent, minimize, or escape the violence, as well as to protect their families. Interviews conducted with women from Latina, Vietnamese, and South Asian backgrounds (Bhuyan, Mell, Senturia, Sullivan, & Shui-Thornton, 2005; Erez & Harley, 2003; Lee, Pomeroy, & Bohman, 2007; Takano, 2006; Yingling, Morash, & Song, 2015), immigrants from Africa (Ting, 2010), and immigrants from Mexico (Brabeck & Guzman, 2008) have helped identify the following ways of coping with IPV:

- Attempting to be unnoticeable. Survivors would attempt to be quiet, be still, and avoid arguments. One woman described “I don’t answer back, ignore, and just stand there and die inside of anger,” while another described “I keep quiet when he is angry and let him do whatever he wants” (Yingling et al., 2014, p. 12).

- Turning to family or friends. Survivors turned to family or friends for emotional help, resources, and help navigating social services. One woman described how she turned to co-workers, stating, “I told women at work. I couldn’t hide what was going on. It was too much to keep to myself”. Another described how turning to neighbors was helpful, reporting, “I talked to a neighbor. She’s the one who told me that you can call police; the police can help you and my husband would be arrested,” (Ting, 2010, p. 354-355).

- Relying on religion or religious leaders. Prayer is a common coping response. One woman reported that prayer “helps me forget the problem for a while, and I feel peace in my mind” (Yingling et al., 2014, p. 13).

- Trying to obey or calm the abuser. One woman described how she tried “staying to myself, doing things the way he wanted them to be done. I did that just to stay alive. It worked, and I stayed alive long enough to get away” (Brabeck, & Guzman, 2008, p. 1287). Another woman reported, “Even though I don’t agree, I end up agreeing with him to avoid more problems” (Ting, 2010).

- Ignoring, denying, or minimizing abuse. “Mainly, I would just try to ignore everything. If he hurt me, I tried to ignore it.” (Brabeck, & Guzman, 2008, p. 1289).

- Accepting fate. Some survivors believed in God’s will or accept karma. “I believe that God will take care for me, that God has a reason for having me suffer, and I believe that God is just, that God will punish my husband for what he did to me. Someday I will get justice and he [her husband] will get his punishment” (Ting, 2010, p. 352).

- Hoping for change in the future. Some women hoped for change in their relationship. One woman described, “I had hope he would change since in my family, my father had changed. [My grandparents] talked to my father, and he changed. He stopped, so I had hope my husband would too. Some men do. I believed it was possible” (Ting, 2010, p. 351). Other women looked forward to a future time when they would be able to leave: “I need him only for now, but when the children are older, and I can work, I will not need his money; I will not need him” (Ting, 2010, p. 351).

- Leaving the room or the home temporarily. Women locked themselves in a closet or left the home to avoid abuse. Women reported that these strategies could provide temporary safety although they were still at risk. For example, one woman who locked herself into a room described how “he’d just unscrew the bolts and open the door” (Brabeck & Guzman, 2008, p. 1288).

- Standing up to the partner by hitting back or talking back. One woman reported, “He would swear at me and put me down, watch me, order me around. I couldn’t stand it. I hit him and ran to the bedroom, locked the door, so he couldn’t come after me” (Yingling et al., 2014, p. 14).

- Seeking Formal Help. Survivors called the police. As one woman described, “I pressed charges and that was freeing. I didn’t want him to do this [abuse] to any other women. I said, this stops right here.” Survivors also accessed advocacy and shelter services. For example, one woman reported, “The shelter is very helpful because I can sleep at night finally, and my son can sleep at night” (Brabeck & Guzman, 2008, p. 1281).

- Leaving partners. When other coping strategies failed, survivors would leave their partners. This required advance planning, including efforts to move to an undisclosed location, disguise oneself, and/or save personal money (Brabeck & Guzman, 2008).A study found that survivors who used a greater variety of strategies were more likely to successfully separate from their abusive partners, and were also more likely to contact family or friends, an advocacy program, and the police (Yingling, et al., 2015). We note that not all survivors chose to leave their partners, and that there are many reasons for this choice. For more information, please see the callout: “Why don’t they just leave?”In one series of interviews about coping with IPV, survivors described how they would add new strategies over time. Survivors generally relied at first on internal resources do deal with IPV. They would begin by trying to tolerate abuse, become unnoticeable, or rely on faith. When this was unsuccessful, they would reach out to family, friends, and professionals for help (Yingling, et al., 2015). Survivors who continued to live with their abusive partners were most likely to use avoidance strategies, attempting to be unnoticeable (Yingling, et al., 2015).

It is important to note that there are some marked differences in help-seeking behaviors that vary by immigrant/refugee background. For example, one study found that Muslim immigrants were less likely than non-Muslim immigrants to call the police, due to fear of spouses, fear of reprisal from family, and a desire to protect their spouses, but they are more likely to have the police become involved due to neighbors or others calling the police (Ammar, Couture-Carron, Alvi, & Antonio, 2013). Another study found that Asian immigrants access mental health services less frequently than immigrants from other areas (Cho & Kim, 2012). Japanese immigrants were less likely than United States-born women of Japanese descent to confront a partner, leave temporarily, or seek help (Yoshihama, 2002). Further, when Japanese immigrants used these strategies, they experienced higher psychological distress compared to Japanese immigrants who did not use them. It is likely that a cultural taboo against these strategies influences both the use of the strategies and feelings after using them (Yoshihama, 2002).

32.6 Barriers to Help Seeking

Support from family, friends, and formal social systems can promote coping after IPV (Coker et al., 2002). Immigrant/refugee women are not likely to seek formal assistance (such as from police or shelters; Ingram, 2007), and are more likely to seek assistance from family and friends (Brabeck & Guzman, 2008). Family and friends provide invaluable support to women who have experienced IPV, including emotional support, information about the system, and suggestions for getting help (Kyriakakis, 2014).

Why don’t they just leave?

Many people wonder why a survivor would choose to stay in a relationship with someone who hurts them. While some partners will choose to end a violent relationship, many will not. Their reasons could vary from ongoing love to pragmatic need to desperate fear, or even a combination of the above.

We describe many reasons why an immigrant/refugee survivor would not leave the relationship or even seek outside help in coping with the relation:

- Commitment to the relationship- Many survivors feel a bond of duty and love to their partner, even when they are sometimes treated poorly.

- Hope for change- Many survivors believe that the violence will go away or get better with time. They may believe that outside circumstances will become less stressful, that their partner will learn how to stop, or that they will be better able to control the situation in the future.

- Parenting Arrangements- A victim may stay in the relationship for the sake of their children, out of a desire for children to live with and be supported by both parents.

- Economic security- The abusive partner may control the finances, leaving the victim without access to resources to provide for self or children.

- Fear for safety- For many survivors, there are real physical threats to leaving the relationship. The abuser may threaten to hurt or even kill them or their children if they leave. When survivors do attempt to leave, many perpetrators will escalate threats and violence.

“For me also, my husband says if I dare put him in jail, when he gets out, he kills me. Then, I ask him to get divorced. He says before getting divorced plan to buy a coffin beforehand. He just says like that.” Khmer Immigrant, quoted in Bhuyan et al., p 912.

Survivors of all backgrounds face substantial barriers to seeking assistance, such as fear of the abuser and retaliation (Bhuyan et al., 2005). Immigrant/refugee survivors, however, face additional social, economic, and legal barriers to seeking informal and formal help for IPV. These challenges include country-of-origin norms, family taboos, distance from or unavailability of supports, fear of deportation or loss of custody, and a lack of culturally competent and language appropriate services.

Country-of-Origin and Family-related Norms

Norms from native countries may impact survivors’ willingness to seek help. In many countries, survivors and their families avoid outside intervention because it might bring shame or dishonor to the family or community (Dasgupta & Jain, 2007; Yoshihama, 2009). Latina and South Asian immigrants/refugees avoid seeking help due to the shame and stigmatization of divorce (Bauer, Rodriguez, Quiroga, & Flores-Ortiz, 2000), and because honorable marriage is one of few ways to maintain others’ respect (Fuchsel et al., 2012). For Vietnamese immigrants/refugees, traditional values, gender roles, and concern about discrimination decrease help seeking (Bui & Morash, 1999).

There may also be norms within the family that prevent help-seeking. Survivors sometimes do not seek help from parents because they do not want family to view their husband in a negative light. Also, they fear that their parents will be distressed and/ or feel shame about the violence (Bhuyan et al., 2005). Women report a taboo against sharing family problems with people outside the family. Also, they worry about gossip within the local immigrant community (Bhuyan et al., 2005; Kyriakakis, 2014).

Distance from or Unawareness of Supports

Families who are nearby can provide more support than families separated by great distances. For example, women living in Mexico often turn to their parents for tangible support such as safe refuge after violence (Kyriakakis, 2014). When these women immigrate to the United States, support from parents in Mexico is primarily emotional (Kyriakakis, 2014). Distance from family can also lead immigrants/refugees to be dependent on an abusive partner for emotional and social support, particularly when English language skills are lacking (Bhuyan et al., 2005; Denham et al., 2007).

Immigrants and refugees may be unaware of local services, such as social and legal service agencies (Bhuyan et al., 2005; Erez et al., 2009; Moya, Chavez-Baray, Martinez, 2014). Further, they might question access to or availability of social services based on prior experiences in their countries-of-origin. For example, in some countries, such as Mexico, the majority of the population do not have access to public social services, and Asian and Latina immigrants often do not believe that anyone is available to help them (Bauer et al., 2000; Bui, 2003; Esteinou, 2007). Even if they have knowledge of these services and how they work, linguistic and cultural barriers can deter seeking help or limit successful navigation of these resources (Bhuyan et al., 2005, Erez et al., 2009).

“In Cambodia, if the husband and wife fight we suffer the pain and only the parents can help resolve to get us back together. We live in America, there are centers to assist us. In Cambodia, there are no such centers to help us.”

-Khmer Immigrant

Quote taken from Bhuyan et al., p. 913

Lack of Language Appropriate and Culturally Competent Services

Language barriers pose a critical problem for community-based organizations and for systems like the police, to communicate with the survivors and their families and to help them effectively (Yingling, et al., 2015; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2009). Further, services, particularly culturally competent services, are not always available to immigrant/refugee women (Morash & Bui, 2008). Community-based organizations and mainstream service providers such as the police need to be trained to understand the complexities of survivors’ lives and to assess common as well as the unique features of IPV experienced by immigrant/refugee women (Messing, Amanor-Boadu, Cavanaugh, Glass, & Campbell, 2013). Also, services providers for immigrant/refugee women must develop awareness about the socio-economic, cultural, and political contexts that these groups of women come from and use that information to develop programs and policies specific to them.

Fellows tour the Genesis Women’s Shelter in Dallas, TX before meeting with a panel of local stakeholders. The Bush Center – Genesis Women’s Shelter & Support – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Video

True Thao, MSW, LICSW discusses the importance of rapport and relationship building when working with immigrant and refugee clients (3:48-8:02).

Fear of Deportation or Loss of Custody

Undocumented immigrants are often afraid to report crimes to the police, including IPV, for fear of deportation or loss of custody (Adams & Campbell, 2012; Akinsulure-Smith et al., 2013). Such fears have likely escalated since the creation of “Secure Communities,” a government program which cross-checks police-recorded fingerprints to identify documentation status. If an undocumented immigrant is processed for a crime, including minor misdemeanors, it can be a first step towards deportation (Vishnuvajjala, 2012). Although many immigrants express fear of deportation if they report IPV, some research studies show that immigrant/refugee women are more likely to report IPV, particularly if they are on a spousal dependent visa and if their abusive partner threatens immigrant action (Raj, Silverman, & McCleary-Sills, 2005).

In some cases, the process of immigration leaves the immigrant spouse/partner dependent on their abusive partner. For example, when someone immigrates with an H1-B visa (targeting highly skilled professionals), their spouses are eligible for an H-4 visa. However, these spouses are not authorized to work, and they cannot file their own application for legal permanent residence status; the H1-B visa holder can choose whether or not to file for residence for his family (Balgamwalla, 2014). This leaves the spouse completely dependent on their partner for documentation for residency and for all economic benefits. Abusive partners can threaten immigration action to maintain control of a partner, by destroying immigration papers, not filing paperwork, or threatening to inform Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE; Balgamwalla, 2014; Erez et al., 2009).

Reporting IPV can also have implications for child custody. Undocumented immigrants can lose custody of their children if claims are brought against them. Also, if a parent accuses their spouse of IPV, the parent can be convicted for failing to protect their children from being exposed to IPV. In select cases, this can lead to deportation and reassignment of custody (Rogerson, 2012).

There are some legal resources for undocumented survivors of IPV. The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) provides protections for survivors of IPV. If a non-citizen is married to a United States permanent resident, they can apply for a “U visa.” These visas give survivors of IPV temporary legal status and the ability to work. However, these are limited to 10,000 per year (Modi, Palmer, & Armstrong, 2014), and often fall short of meeting the needs of the total number of qualified partners (Levine & Peffer, 2012).

Economic Dependency

Immigrants/refugees who are unemployment depend on their partner to provide for themselves and their children and may avoid any reporting that could jeopardize the relationship (Bui & Morash, 2007). In some cases, gender norms may discourage pursuing education or employment, which facilitates dependency (Bhuyan et al., 2005). The majority of immigrant/refugee survivors have limited economic resources (Erez et al., 2009; Morash et al., 2007). When immigrant/refugee women have access to employment, it can lead to an increase in couple conflict due to extra responsibilities placed on both the partners, but it can also empower immigrant/refugee women to demand better treatment (Grzywacz, Rao, Gentry, Marin, & Arcury, 2009).

Ties that Bind

Even when IPV is present, most relationships also have positive components. Survivors often hope to remain in the relationship because of these components. For immigrants/refugees, the pull to stay with a violent partner may be even stronger. Two IPV advocates stated: “a battered immigrant woman who is in an intimidating and unfamiliar culture may find comfort and continuity with an abuser” (Sullivan & Orloff, 2013). Relationships are ties that bind, and partners cannot overlook their long history together, often beginning before immigration (Sullivan, Senturia, Negash, Shiu-Thornton, & Giday, 2005).

Throughout the experience of IPV, survivors must weigh the benefits and costs of remaining the relationship. They make changes to alleviate current pain and to prevent future incidents. Perpetrators make similar choices and changes. Some perpetrators are able to make choices that reduce or stop violence altogether. In order to have a stable family relationship, both partners must make decisions that protect the physical, emotional, financial, and social health of all members.

Impact on Children

Witnessing IPV is a harrowing experience for children. Children who witness IPV are more likely to experience mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD, as well as internalizing and externalizing problems (Kitzmann et al., 2003; Wolfe et al., 2003). While very little research has assessed the experience of IPV or family violence (violence against the child themselves or witnessing violence towards another family member) among immigrant/refugee children specifically, we do know that they are heightened risk of witnessing IPV. Many refugees are at risk for IPV and family violence due to their experiences of conflict and violence in their countries-of-origin (Haj-Yahia & Abdo-Kaloti, 2003; Catani, Schauer, & Neuner, 2008).

Research with children living in conflict-affected areas underscores the negative impact of IPV on children. Research shows that family violence is an even stronger predictor of PTSD in children than war exposure (Catani et al., 2008). In a sample of children exposed to war, tsunami, and family violence, 14% identified family violence as the most distressing event of their lives (Catani et al., 2008). Immigrant/refugee children exposed to family violence face a unique set of stressors. They must cope with the experiences of family violence alongside the stressors of trauma and/or relocation.

Where’s Waldo?

There are several key people who are missing or hard to find in this chapter. Can you find them?

Where are the perpetrators?

You may have noticed that this chapter focuses on the survivors of IPV, and that the perpetrator’s perspective is rarely mentioned. Almost no research has been done with the perpetrators of IPV among immigrants/refugees.

Where are the men?

You can see that in all of the research we talk about, the survivor is a woman. We know that women are also perpetrators of IPV, and that men are also survivors of IPV (CDC, 2003). However, the vast majority of all research on survivors has studied women exclusively. This focus has likely arisen because women are more commonly injured by IPV (Whitaker, Haileyesus, Swahn, & Saltzman, 2007). It is nonetheless important to hear the stories of all people, regardless of gender.

Where are the children?

You might have noticed that in the introduction, we mentioned that children experience very negative effects from seeing IPV. But this section and the “Impact on Children” sections are the only time we mention them. Why? Once again, very little research has looked at the experience of IPV among immigrant/refugee children.

IPV is an issue that affects every member of the family – perpetrator, victim, and children. As you read the chapter, try to consider what the perspectives might be of the perpetrator and children in each story.

32.7 Future Decisions

What can be done to prevent and intervene with IPV among immigrants/refugees? We have several suggestions for research and practice to address this critical problem. First, researchers must evaluate if IPV in immigrant and refugee families has distinct etiologies, characteristics, and outcomes compared to non-immigrant and non-refugee families. As we discussed in the “Where’s Waldo” sidebar, very little research has captured IPV perpetrators’ perspectives. We urge researchers to particularly assess the features of IPV perpetration among immigrants/refugees. This research will guide prevention and intervention work among immigrants and refugees. Effective programs must: 1) be available in the immigrants’ language; 2) be adapted to be culturally appropriate for the immigrants’ background; 3) reframe cultural norms; and 4) encourage healthy relationships (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2009). Perpetrators are also in need of culturally specific programs. Such programs could include psychoeducation about IPV and culturally specific practices that call for respecting women (Rana, 2012).

Immigrant/refugee survivors describe word-of-mouth as the most effective way to increase awareness of IPV and resources to address it. They propose a call to action to prevent and address IPV. Through conversation, we can help our community members know about available resources. Everyone is called to be a part of “increasing the visibility of people affected by IPV, working for equality, and raising awareness” (Moya et al., 2014).

32.8 Case Study

Sabeen and Alaa are a couple in their late 20’s from Syria, and they have a three-year-old daughter named Mais. For many years, Alaa worked as an office manager at a local hospital. However, when the increasing conflict led to deaths of many neighbors, the couple fled together to Jordan. In the refugee camp, the family lived alongside many other families in very cramped quarters. Alaa tried to get food and water for the family daily, but resources were limited and he often came home feeling both inadequate and frustrated. One night when he was especially hungry, Mais began acting defiant. Alaa turned to Sabeen and angrily asked why she couldn’t manage their daughter anymore, slapping her across the face. Sabeen was shocked – this had never happened before. Alaa looked sad, and they both got quiet for a minute. They each wished they could go somewhere to just think and be alone, but there was nowhere in the camp to go. They already knew their neighbors must have heard the fight.

As pressures in the camp mounted and resources became scarcer, Alaa more frequently hit Sabeen. They both talked about how they looked forward to when they could be relocated when life would be calmer, and their relationship would be better. When they were given refugee status and arrived in the United States, things were better – for a while. But after a few months, Sabeen had found work cleaning homes, but there was less work available for men. With nothing to do and few people to talk to, Alaa began to drink. As he became more and more aggressive, Sabeen became more and more depressed, not knowing how to respond. She once tried to call for help from a neighbor, but the neighbor either did not understand her English or did not respond. She decided it was better to try to manage the home well in order to try to avoid any outbursts, but her energy sagged lower and lower. In their small one-bedroom apartment, Mais would always manage to hide under blankets when her dad started yelling.

One day, Sabeen decided to talk to a fellow refugee about their family situation. It felt good to talk about it, and the friend said Sabeen could always come over to their apartment if she needed to get away for an evening. Sabeen started leaving the house with Mais right after an outburst started before things could escalate too far. Around this time, Alaa found a job. He started to become less violent, and the outbursts grew less and less frequent.

Context for case study taken from Leigh, 2014.

32.9 End-of-Chapter Summary

Discussion Questions

- Think about your cultural background. What aspects of your background might increase tolerance of IPV? What aspects would reduce tolerance of IPV?

- What pressures do immigrant/refugee families face, and how might that increase risk of IPV?

- How might someone experience a feeling of loss of control, despite moving to a country with better safety and economic opportunities?

- What are some possible consequences for children exposed to IPV?

Helpful Links

National Domestic Violence Hotline

- The Hotline maintains lists of resources for survivors, perpetrators, and friends. They have screening tests if you are worried you might be experiencing IPV, and tips for safety at every stage. They also maintain stories from survivors. They have a 24/7 chatline available for support.

- http://www.thehotline.org/

VAWnet (Online network provided by the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence)

- This site maintains resources relating to women, children, and immigration.

- https://vawnet.org/sc/domestic-violence-immigrant-communities

References

Abamzon, S. (2012). Colombia. In Malley-Morrison, K. (Ed) (2004). International perspectives of family violence and abuse: A cognitive ecological approach. Routledge.

Adams, M. E. & Campbell, J. (2012). Being undocumented and intimate partner violence (IPV): Multiple vulnerabilities through the lens of feminist intersectionality. Women’s Health and Urban Life, 11(1), p. 15.

Akinsulure-Smith, A. M., Chu, T., Keatley, E., & Rasmussen, A. (2013). Intimate partner violence among West African Immigrants. Journal of Aggression and Maltreatment Trauma, 22(1), 10-129. Doi: 10.1080.10926771.2013.719592.

Ammar, N., Couture-Carron, A., Alvi, S., & Antonio, J. S. (2013). Experiences of Muslim and Non-Muslim battered immigrant women with the police in the United States: A closer understanding of commonalities and differences. Violence Against Women, 19(12), 1449-1471. doi:10.1177/1077801213517565

Balgamwalla, S. (2014). Bride and prejudice: How U.S. immigration law discriminates against spousal visa holders. Berkeley Journal Of Gender, Law & Justice,29(1), 25-71.

Bauer, H. M., Rodriguez, M. A., Quiroga, S. S., & Flores-Ortiz, Y. G. (2000). Barriers to health care for abused Latina and Asian immigrant women. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 11(1), 33-44. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0590

Bhuyan, R., Mell, M., Senturia, K., Sullivan, M., & Shiu-Thornton, S. (2005). “Women must endure according to their karma”: Cambodian immigrant women talk about domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(8), 902-921.

Biafora F., & Warheit G. (2007). Self-reported violent victimization among young adults in Miami, Florida: Immigration, race/ethnic and gender contrasts. International Review of Victimology, 14, 29-55

Black, M.C., Basile, K.C., Breiding, M.J., Smith, S.G., Walters, M.L., Merrick, M.T., Chen, J., & Stevens, M.R. (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Brabeck, K.M. & Guzmán, M.R. (2008). Frequency and perceived effectiveness of strategies to survive abuse used by battered Mexican-origin women. Violence Against Women, 14,1274-1294.

Brecklin, L. R. (2002). The role of perpetrator alcohol use in the injury outcomes of intimate assaults. Journal of Family Violence, 17, 185–197.

Breiding, M. J., Basile, K. C., Smith, S. G., Black, M. C., Mahendra, R. R. (2015). Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 2.0. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bui, H. N. (2003). Help-seeking behavior among abused immigrant women. Violence Against Women, 9, 207-239.

Bui, H. N. & Morash, M. (2007). Social capital, human capital, and reaching out for help with domestic violence: A case study of women in a Vietnamese American community. Criminal Justice Studies: A Critical Journal of Crime, Law and Society, 20 (4), 375-390.

Bui, H. N. & Morash, M. (1999). Domestic violence in the Vietnamese immigrant community: An exploratory study. Violence Against Women, 7, 768-795.

Caetano, R., Cunradi, C. B., Clark, C. L., Schafer, J. (2000). Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among White, Black and Hispanic couples. Journal of Substance Abuse, 11(2):123–138. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00015-8.

Caetano, R., Ramisetty-Mikler, S., Caetano, V., Haris, T. R. (2007). Acculturation stress, drinking, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the U.S. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(11), 1431-1447.

Catani, C., Jacob, N., Schauer, E. (2008). Family violence, war, and natural disasters: a study of the effect of extreme stress on children’s mental health in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 33.

Center for Disease Control. (2003). Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2003. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/IPVBook-a.pdf

Cho, H., & Kim, W. (2012). Intimate partner violence among Asian Americans and their use of mental health services: Comparisons with White, Black, and Latino Victims. Journal Of Immigrant & Minority Health, 14(5), 809-815. doi:10.1007/s10903-012-9625-3

Coker, A. L., Smith, P. H., McKeown, R. E., & King, M. J. (2002). Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 553-559.

Cook, B., Alegria, M., Lin, J. Y., & Guo, J. (2009). Pathways and correlates connecting exposure to the US and Latino mental health. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 2247–2254.

Dasgupta, S. D., & Jain, S. (2007). Ahimsa and the contextual realities of woman abuse in the Jain community. In S. D. Dasgupta, Body Evidence: Intimate Violence against South Asian Women in America, p. 152. Rutgers University Press.

Denham, A. C., Frasier, P. Y., Gerken Hooten, E., Belton, L., Newton, W., Gonzales, P., et al. (2007). Intimate partner violence among Latinas in Eastern North Carolina. Violence Against Women, 13, 123-140.

Dutton, M., Orloff, L, and Hass. G.A. (2000). Characteristics of help-seeking behaviors, resources, and services needs of battered immigrant latinas: Legal and policy implications.” Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law and Policy, 7.

Erez, E., & Hartley, C. C. (2003). Battered immigrant women and the legal system: A therapeutic jurisprudence perspective. Western Criminology Review, 4, 155-169.

Erez, E., Adelman, M., & Gregory, C. (2009). Intersections of Immigration and Domestic Violence. Voices of Battered Immigrant Women. Feminist Criminology, 4(1), 32-59.

Esteinou, R. (2007). Strengths and challenges of Mexican families in the 21st century. Marriage and Family Review, 41, 309-334. doi: 10.1300/J002v41n03_05

Fedovskiy, K., Higgins, S., & Paranjape, A. (2008). Intimate partner violence: how does it impact major depressive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder among immigrant Latinas? Journal Of Immigrant & Minority Health, 10(1), 45-51.

Fife, R. S., Ebersole, C., Bigatti, S., Lane, K., & Huber, L. B. (2008). Assessment of the relationship of demographic and social factors with intimate partner violence (IPV) among Latinas in Indianapolis. Journal of Women’s Health, 17(5), 769-775. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0759

Flores, E., Tschann, J. M., Marin, B. V., & Pantoja, P. (2004). Marital conflict and acculturation among Mexican American husbands and wives. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(1), 39-52.

Frye, V., Hosein, V., Waltermaurer, E., Blaney, S., & Wilt, S. (2005). Femicide in New York City: 1990-1999. Homicide Studies, 9(3), 204-228.

Fuchsel, C. L. M., Murphy, S. B., & Dufresne, R. (2012). Domestic violence, culture, and relationship dynamics among immigrant Mexican women. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work, 27, 263–274. doi:10.1177/0886109912452403.

Garcia, L., Hurwitz, E. L., Krauss, J. F. (2005). Acculturation and reported intimate partner violence among Latinas in Los Angeles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 569–590. doi: 10.1177/0886260504271582

Grzywacz, J. G., Rao, P., Gentry, A., Arcury, T. A., & Marín, A. (2009). Acculturation and Conflict in Mexican Immigrants’ Intimate Partnerships: The Role of Women’s Labor Force Participation. Violence Against Women, 15(10), 1194-1212. doi:10.1177/1077801209345144

Gupta, J., Acevedo-Garcia, D., & Hemenway, D. (2009). Premigration Exposure to Political Violence and Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence Among Immigrant Men in Boston. American Journal of Public Health, 99(3), 462-469. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.120634

Gupta, J., Acevedo-Garcia, D., Hemenway, D., Decker, M. R., Raj, A., Silverman, J. G. (2010). Intimate partner violence perpetration, immigration status, and disparities in a community health center-based sample of men. Public Health Rep, 125(1), 79-87.

Haj-Yahia, M. M., & Abdo-Kaloti, R. (2003). The rates of correlates of the exposure of the exposure of Palestinian adolescents to family violence toward an integrative-holistic approach. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27, 781-806.

Hass, G. E., Dutton, M. A., Orloff, L. E. (2000). Lifetime prevalence of violence against Latina immigrants: legal and policy implications. International review of victimology, 7(1-3). Doi: 10.1177/026975800000700306

Hazen, A. L., & Soriano, F. I. (2007). Experiences with intimate partner violence among Latina women. Violence Against Women, 13(6), 562-582.

Hazen, A., & Soriano, F. I. (2005). Experience of intimate partner violence among U.S. born, immigrant, and migrant Latinas. National Institute of Justice. Retrieved from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/211509.pdf

Ingram, E. M. (2007). A comparison of help seeking between Latino and non-Latino victims of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 13, 159-171.

Jewkes, R., Jonathan L., & Loveday P. (2002). “Risk factors for Domestic violence: findings from a South African cross-sectional study.” Social Science & Medicine, 55, 1603–17.

Jin, X., & Keat, J. E. (2010). The effects of change in spousal power on intimate partner violence among Chinese immigrants. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(4):610–625. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334283.

Kim-Godwin, Y., Maume, M., & Fox, J. (2014). Depression, Stress, and Intimate Partner Violence Among Latino Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers in Rural Southeastern North Carolina. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health, 16(6), 1217-1224. doi:10.1007/s10903-014-0007-x

Kitzmann, K. M., Gaylord, N. K., Holt, A. R., & Kenny, E. D. (2003). Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 339-352.

Koenig, M. A., Stephenson, R., Ahmed, S., Jejeebhoy, S. J., & Campbell, J. (2006). Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in north India. American Journal of Public Health, 96(1), 132–138. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872

Kyriakakis, S. (2014), Mexican immigrant women reaching out: The role of informal networks in the process of seeking help for intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 20 (9), 1097-1116.

Lau, A. S., Takeuchi, D. T. and Alegría, M. (2006), Parent-to-child aggression among asian american parents: Culture, context, and vulnerability. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 1261–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00327.x

Lee, J., Pomeroy, E. C., Bohman, T. M. (2007). Intimate partner violence and psychological health in a sample of Asian and Caucasian women: The role of social support and coping. Journal of Family Violence, 22(8), 709-720. Retrieved from: http://aquila.usm.edu/fac_pubs/1887

Leigh, K. (2014). Domestic violence on the rise among Syrian refugees. New York Times. Retrieved from: http://kristof.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/08/29/domestic-violence-on-the-rise-among-syrian-refugees/?_r=1

Levine, H., & Peffer, S. (2012). Quiet casualties: An analysis of non-immigrant status of undocumented immigrant victims of intimate partner violence. International Journal Of Public Administration, 35(9), 634-642. doi:10.1080/01900692.2012.661191

Makahamadze, T., Isacco, A., & Chireshe, E. (2012). Examining the perceptions of Zimbabwean women about the domestic violence act. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 706-727. doi: 10.1177/0886260511423239

Malley-Morrison, K. (Ed) (2004). International perspectives of family violence and abuse: A cognitive ecological approach.

Messing, J. T., Amanor-Boadu, Y., Cavanaugh, C. E., Glass, N. E., Campbell, J. C. (2013). Culturally competent intimate partner violence risk assessment: Adapting the danger assessment for immigrant women. Social Work Research, 37(3), 263-275.

Modi, M. N., Palmer, S., & Armstrong, A. (2014). The role of violence against women act in addressing intimate partner violence: A public health issue. Journal of Women’s Health, 23(3), 253-259. doi:10.1089/jwh.2013.4387

Morash, M. & Bui, H. N. (2008). The connection of U.S. best practices to outcomes for abused Vietnamese-American women. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 32, 221-243

Morash, M., Bui, H. N., Zhang, Y. & Holfreter, K. (2007). Risk factors for abusive relationships: A study of Vietnamese-American immigrant women. Violence Against Women, 13, 653-675.

Moya, E., Chavez-Baray, S., & Martinez, O. (2014). Intimate partner violence and sexual health: Voices and images of latina immigrant survivors in the southwest United States. Health Promotion Practice; doi: 10.1177/1524839914532651

Nava, A., McFarlane, J., Gilroy, H., & Maddoux, J. (2014). Acculturation and associated effects on abused immigrant women’s safety and mental functioning: Results of entry data for a 7-year prospective Study. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health, 16(6), 1077-1084. doi:10.1007/s10903-013-9816-6

Raj, A., & Silverman, J. (2002). Violence against immigrant women. Violence Against Women 8, 367-398.

Raj, A., Silverman, J. G., McCleary-Sills, J., Liu, R. (2005). Immigration policies increase south Asian immigrant women’s vulnerability to intimate partner violence. Journal of American Medical Women’s Association, 60, 26–32

Rana, S. (2012). Addressing Domestic Violence in Immigrant Communities: Critical Issues for Culturally Competent Services. Harrisburg, PA: VAWnet, a project of the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. Retrieved from: http://www.vawnet.org

Rhee, S. (1997). Domestic violence in the Korean immigrant family. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 24, 63-77.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2009). Intimate partner violence in immigrant and refugee communities: Challenges, promising practices and recommendations. Retrieved from: www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2009/03/intimate-partner-violence-in-immigrant-and-refugee-communities.html

Rogerson, S. (2012). Unintended and unavoidable: The failure to protect rule and its consequences for undocumented parents and their children. Family Court Review, 50(4), 580-593. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2012.01477.x

Sabina, C., Cuevas, C. A., Lannen, E. (2014). The likelihood of Latino women to seek help in response to interpersonal victimization: An examination of individual, interpersonal and sociocultural influences. Psychosocial Intervention, 23(2), 95-103. doi: 10.1016/j.psi.2014.07.005

Saltzman, L. E., Fanslow, J. L., McMahon, P. M., Shelley, G. A. (2002). Intimate partner violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Segura, C. (2015, Mar). Colombia continues to legitimize violence against women. Elespectador. Retrieved from: http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/politica/colombia-sigue-legitimando-violencia-contra-mujer-articulo-547754

Shiu-Thornton, S., Senturia, K., & Sullivan, M. (2005). “Like a bird in a cage”: Vietnamese women survivors talk about domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 8, 959-976.

Simonelli, C. J., Mullis, T., Elliot, A. N., & Pierce, T. W. (2002). Abuse by siblings and subsequent experiences of violence within the dating relationship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17, 103-121.

Sullivan, K., & Orloff, L. (2013). Breaking barriers: A complete guide to legal rights and resources for battered immigrants. Retrieved from http://niwaplibrary.wcl.american.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/pdf/FAM-Manual-Full-BreakingBarriers07.13.pdf

Sullivan, M., Senturia, K., Negash, T., Shiu-Thornton, S., & Gidav, B. (2005). For us it is like living in the dark: Ethiopian women’s experiences with domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(8), 922-940.

Takano, Y. (2006). Coping with domestic violence by Japanese Canadian women. In P. T. P. Wong & L.C.J. Wong (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 319–360). New York: Springer.

Ting, L. (2010). Out of Africa: coping strategies of African immigrant women survivors of intimate partner violence. Health Care For Women International, 31(4), 345-364. doi:10.1080/07399330903348741

Vishnuvajjala, R. (2012). Insecure communities: How an immigration enforcement program encourages battered women to stay silent. Boston College Journal of Law and Social Justice, 32(1).

Whitaker, D. J., Haileyesus, T., Swahn, M., & Saltzman, L. S. (2007). Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health, 97(5), 941–947. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020

Wolfe, D. A., Crooks, C. V., Lee, V., McIntyre-Smith, A., & Jaffe, P. G. (2003). The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: a meta-analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(3), 171-187.

Wong, F. Y., DiGiani, J., Young, D., Huang, Z. J., Smith, B. D., & John, D. (2011). Intimate partner violence, depression, and alcohol use among a sample of foreign-born Southeast Asian women in an urban setting in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(2), 211-229. Doi: 10.1177/0886260510362876

World Health Organization. (2017). Violence against women. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs239/en/

Yingling, J., Morash, M., & Song, J. (2015). Outcomes associated with common and immigrant-group-specific responses to intimate terrorism. Violence Against Women, 21(2), 206-228.

Yoshihama, M. (2009). Battered women’s coping strategies and psychological distress: Differences by immigration status. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(2), 429-452.

Yoshihama, M., Blazevski, J., & Bybee, D. (2014). Enculturation and attitudes toward intimate partner violence and gender roles in an Asian Indian populations: Implications for community-based prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(3), 249-260.

Yoshioka, M. R., DiNoia, J., & Ullah, K. (2001). Attitudes toward marital violence: An examination of four Asian communities. Violence against Women, 7(8), p. 900-926.

Yoshioka, M. R., Dang, Q., Shewmangal, N., Vhan, C., & Tan, C. I. (2000). Asian family violence report: A study of the Cambodian, Chinese, Korean, South Asian, and Vietnamese communities in Massachusetts. Asian Task Force Against Domestic Violence: Boston, MA.

Zarza, M. J., Ponsoda, V., & Carrillo, R. (2009). Predictors of violence and lethality among Latina immigrants: Implications for assessment and treatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 18(1), 1-16. doi:10.1080/10926770802616423

Attribution

Adapted from Chapters 1 through 9 from Immigrant and Refugee Families, 2nd Ed. by Jaime Ballard, Elizabeth Wieling, Catherine Solheim, and Lekie Dwanyen under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.