Chapter 33: Embracing a New Home: Resettlement Research & the Family

Learning Objectives

- Learn from the national and global perspectives of immigrants and refugees resettling.

- Recognizing that the world is constantly and rapidly changing.

- Recognizing that Global/national/international events can have an impact on individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities.

- Global implications dictate that we foster international relationships and opportunities to address international concerns, needs, problems, and actions to improve the well-being of not only U.S. citizens, but global citizens.

35.1 Introduction

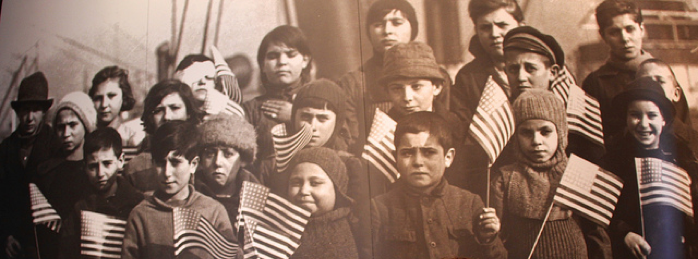

The movement of people to the United States from all parts of the world has resulted in a very diverse and ever-evolving nation that can perhaps be described as a mosaic of cultures, races, and ethnicities. How does a nation achieve social cohesion in the midst of evolving diversity? How do individuals and families hold the complexities of honoring their home culture and reaching their goals in the new country and culture?

Because migration experiences are diverse, the process of resettlement is also varied and must be examined through lenses of race, ethnicity, nativity, gender, political orientation, religion, and sexuality, among others. In this chapter, we will conduct a historical review of the theories that have been used to assess the processes of resettlement. We begin by describing assimilation, acculturation, and multiculturalism – early theories that emphasized group processes. We will then describe the transition to intersectionality, and its focus on individual process. Finally, we will identify family theories and their potential role in the future of research on resettlement.

Blendine Perreire Hawkins (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota) and Jaime Ballard (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota)

35.2 Assimilation

Classic assimilation theory or straight-line assimilation theory can be dated back to the 1920s originating from the Chicago School of Sociology (Park, Burgess, & McKenzie, 1925; Waters, Van, Kasinitz, & Mollenkopf, 2010). This early assimilation model set forth by Park (1928) described how immigrants followed a straight line of convergence in adopting “the culture of the native society” (Scholten, 2011). In many ways, assimilation was synonymous with ‘Americanization’ and interpreted as ‘becoming more American’ or conforming to norms of the dominant Euro-American culture (Kazal, 1995). Assimilation theory posited that immigrant assimilation was a necessary condition for preserving social cohesion and thus emphasized a one-sided, mono-directional process of immigrant enculturation leading to upward social mobility (Warner & Srole 1945). Assimilation ideas have been criticized for lacking the ability to differentiate the process of resettlement for diverse groups of immigrants; they fail to consider interacting contextual factors (van Tubergen, 2006).

Segmented assimilation theory emerged in the 1990s as an alternative to classical assimilation theories (Portes & Zhou, 1993; Waters et al., 2010). Segmented assimilation theory posits that depending on immigrants’ socioeconomic statuses, they may follow different trajectories. Trajectories could also vary based on other social factors such as human capital and family structure (Xie & Greenman, 2010). This new formulation accounted for starkly different trajectories of assimilation outcomes between generations and uniquely attended to familial effects on assimilation. The term often employed when one group is at a greater advantage and is able to make shifts more readily is segmented assimilation (Boyd, 2002).

Later, Alba and Nee (2003) formulated a new version of assimilation, borrowing from earlier understandings yet rejecting the prescriptive assertions that later generations must adopt Americanized norms (Waters et al., 2010). Within their conceptualization, assimilation is the natural but unanticipated consequence of people pursuing such practical goals of getting a good education, a good job, moving to a good neighborhood and acquiring good friends (Alba & Nee, 2003).

Numerous studies have utilized assimilation theories to guide their inquiry with diverse foci like adolescent educational outcomes, college enrollment, self-esteem, depression and psychological well-being, substance use, language fluency, parental involvement in school, and intermarriage among other things (Waters & Jimenez, 2005; Rumbaut, 1994). Despite such widespread use of assimilation, some scholars have noted that the theory may not adequately explain immigrants’ diverse and dynamic experiences (Glazer, 1993) and some note that other theories such as models of self-esteem or social identity may be added to assimilation to bolster its value (Bernal, 1993; Phinney, 1991).

A further critique is that a push for assimilation may mask an underlying sentiment that immigrants and refugees are unwelcome guests who have to compete for scarce resources (Danso, 1999; Danso & Grant, 2000). These sentiments can impact the reception and adaptation experiences of immigrant populations in the receiving country (Esses, Dovidio, Jackson, & Armstrong, 2001). Extreme nationalism and a sense of fear may encourage ideals of conformity that defines ‘successful integration’ or ‘successful resettlement’ as full adoption of the receiving country’s ways and beliefs while giving up old cultures and traditions. There is little or no support for the maintenance of cultural or linguistic differences, and groups’ rights may be violated. This belief can lead to misunderstandings when new United States residents speak, act, and believe differently than the dominant culture. It can result in an unwelcoming environment and prevent the development and offering of culturally and linguistically appropriate services for immigrant and refugee families, erecting barriers to their opportunity to adapt and thrive in their new homes. Assimilation may implicitly assume that some cultures and traits are inferior to the dominant White-European culture of the receiving nation and therefore should be abandoned for ways more sanctioned by that privileged group.

Acculturation and Adaptation

Later Milton Gordon’s newer multidimensional formulation of assimilation theory provided that ‘acculturation,’ which refers to one’s adoption of the majority’s cultural patterns, happens first and inevitably (1964). Contemporary acculturation models embrace some of the previous ideas of assimilation but can be less one-dimensional (Berry, 1990). At times, the terms assimilation and acculturation have been used interchangeably. John Berry employed the concept of acculturation and identified 4 modes: integration (where one accepts one’s old culture and accepts one’s new culture), assimilation (where one rejects one’s old culture and accepts one’s new culture), separation (where one accepts one’s old culture and rejects one’s new culture), and marginalization (where one rejects one’s old culture and also rejects one’s new culture) (Berry, 1990). This understanding of acculturation proposes that immigrants employ one of these four strategies by asking how it may benefit them to maintain their identity and/or maintain relationships with the dominant group, and does not assume that there is a typical one-dimensional trajectory they would follow.

While assimilation is applied to the post-migration experience generally, acculturation refers to the psychological or intrapersonal processes that immigrants experience (Berry, 1997). Hence, the concept of acculturative stress –linked to psychological models of stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) arose to describe how incompatible behaviors, values, or patterns create difficulties for the acculturating individual (Berry, Kim, Minde, & Mok, 1987). Adaptation has been used in recent years to refer to internal and external psychological outcomes of acculturating individuals in their new context, such as a clear sense of personal identity, personal satisfaction in one’s cultural context, and an ability to cope with daily problems (Berry, 1997).

Much of the discourse concerning adaptation has focused on the socio-economic adaptation of immigrants as measured by English language proficiency, education, occupation, and income. When culture is included, the emphasis is typically on concepts of ethnic intermarriage and language proficiency (van Tubergen, 2006). Much less attention has been paid to how immigrants form attachments to their new society, subjective conceptions of ‘success’ in the new country, or to the factors that lead some immigrants to retain distinct characteristics and identities but adopt to new ways of being. Some have gone further to identify three types of adaptation: psychological, sociocultural, and economic (Berry, 1997).

Videos

Paul Orieny, Sr. Clinical Advisor for Mental Health, The Center for Victims of Torture (CVT), discusses the challenges of coping with the magnitude of change encountered during resettlement (0:00-4:28).

True Thao, MSW, LICSW discusses cultural change and adaptations experienced by immigrants and refugees (1:43-2:40)

Multiculturalism and Pluralism

Theories of assimilation, acculturation, and adaptation are all focused on the immigrant. This is not to say that these theories have not included the receiving society or the dominant group’s influence on the immigrant. However, a different way to conceptualize the post-migration experience may be by exploring how any society can support multicultural individuals both, United States-born and foreign-born, and how adjustments and accommodations are made by both the receiving culture and the immigrant culture to aid resettlement.

Multiculturalism and pluralism are often understood as the opposite of assimilation (Scholten, 2011), emphasizing a culturally open and neutral understanding of society. These ideas purport that diverse people need freedom to determine their method of resettlement and the degree to which they will integrate. A nation that embraces a multicultural view may promote the preservation of diverse ethnic identities, provide political representation, and protect rights of minority populations (Alba, 1999; Alexander, 2001). There are those, especially more liberally minded groups that support the idea that immigrant groups should not be judged according to their religion, skin color, ability or willingness to assimilate, language, or what is deemed culturally useful. Because multiculturalism acknowledges differences and responds to inequality in a society, critics charge that it is a form of ethnic or “racial particularism” that goes against the solidarity on which the United States democracy stands (Alexander, 2001, p. 238). Behind every policy are assumptions that implicitly or explicitly support a vast theoretical and ideological continuum. With the ebb and flow of immigration throughout the history of this country, some of these ideological positions have shifted, and also residuals of traditional nationalistic ideals remain.

Intersectionality Theory

The lessons learned from earlier conceptualizations of immigrant resettlement are 1) that an accurate understanding of resettlement is flexible, dynamic, and heterogeneous; 2) that resettlement itself is a synergistic process between the newcomer and the receiving society; and 3) that ultimately the knowledge of how resettlement is experienced is best understood from the standpoint of an immigrant. Thus in many ways, the discourse about immigrant experiences has shifted from an emphasis on group processes to individual processes. Contemporary scholars are beginning to explore the theory of intersectionality as a lens to understand immigrant identities and adaptation to receiving countries (Cole, 2009; Shields, 2008). Intersectionality theory allows for an understanding of the complex intersections of an individual’s identities shaped by the groups to which an individual belongs or to which s/he is perceived to belong, along with the interacting effects of an individual and the different contexts they are in. Intersectionality theory does not claim to be apolitical; it posits that an accurate understanding of the experiences of marginalization requires knowledge of broad historical, socio-political, cultural, and legal contexts. While theories of assimilation and acculturation tend to endorse integration – a stage in which an immigrant has successfully integrated their culture or origin and new culture (Sakamoto, 2007), intersectionality theory proposes that structural issues such as discrimination, migration policy, and disparity inaccessibility of resources based on language or nationality, affect an immigrant’s ability or desire to integrate.

Intersectionality is a feminist sociological theory developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989), which posits that one, cannot truly arrive at an adequate understanding of a marginalized experience by merely adding the categories such as gender plus race, plus class, etc. Rather these identity categories must be examined as interdependent modes of oppression structures that are interactive and mutually reinforcing.

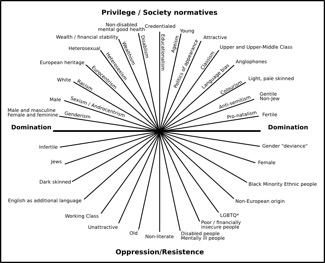

Intersectionality rests on three premises. First, it is believed that people live in a society that has multiple systems of social stratification. They are afforded resources and privileges depending on one’s location in this hierarchy (Berg, 2010). Social stratification can best be understood by accepting the premise that there are forms of social division in society that are based on identities or attributes, such as gender, race, nativity, class, etc. Within society, some of these social divisions are more valued than others, thus creating a hierarchy, or in cruder terms, a pecking order. These divisions and hierarchy are arbitrary in that they are socially constructed and have no essential meaning but have been established by those in power and maintained by society historically. Those deemed higher on the hierarchy and having more ‘status’ are provided with power and privileges and those deemed lower on the hierarchy are not (Anthias, 2001). Much research has been conducted on gender inequalities (Pollert 1996, Gottfried, 2000), ethnic inequalities (Modood et al., 1997) and class inequalities (Anthias & Yuval Davis, 2005; Bradley, 1996), providing evidence for the social constraints in the shape of sexism, racism, classism, etc.

The second premise on which intersectionality rests is that social stratification systems are interlocked. Every individual may hold different positions in different systems of stratification at the same time; there is not only variation among groups of people but within groups of people (Weber, 1998). The implications of this premise for immigrant populations are profound; individuals within immigrant communities may not have the same experiences adjusting to a new society given the varied positions they hold within different contexts based on their identities and attributes.

Within intersectionality theory, an individual has multiple intersecting identities. These identities are informed by group memberships such as gender, class, race, sexuality, ethnicity, ability, religion, nativity, gender identity, and more (Case, 2013). Intersecting identities place an individual at a particular social location. Individuals may have similar experiences with other individuals within one community, such as similar experiences to others of their nation of origin, but their experiences may also be quite different depending on other identities they hold.

For example, an immigrant is not only from Central American and female but is a Latina woman, two identities that when combined, create her unique experience.

There are pressures to conform to the expectations of each social group to which an individual belongs. Each cultural community has images, expectations, and norms associated with it. These ideas vary by culture and generation because they are constructed for that time, group, and purpose. Conformity to expectations of a social group has both tangible and intangible benefits (Cialdini, 2001), not the least of these is the benefit of affiliation (Cialdini & Trost 1998). There has been much research about conflict and dissonance that can arise from an individual’s pressure to identify with the larger social groups and contexts, and also reaffirm their identity within their family’s cultural group or the culture of their country of origin (Farver, Narang, & Bhadha, 2002; Phinney, Horenczyk, Liebkind, & Vedder, 2001; Rumbaut, 1994).

The third premise of intersectionality is that where one is located within this complex social stratification system will consequently influence one’s worldview. This is logical given that each individual has different experiences depending on where they are located within the social stratification system (Demos & Lemelle, 2006). This speaks to one’s positionality – a person’s location across various axes of social group identities which are interrelated, interconnected, and intersecting. One’s position informs one’s unique standpoint. Furthermore, these identities may be external/visible, such as race and gender, or internal/invisible, such as sexuality or nativity, and carry privileges or limit choices depending upon one’s positionality. Thus one’s position and standpoint may be the most suitable way in which to frame and understand the discussion of immigrant resettlement. An example would be how research has indicated that skin color, often a physical feature that indicates identity, affects how immigrant experiences and adapts to their new society (Telzer & Garcia, 2009; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007).

The concept of intersectionality has been revolutionary in conceptualizing the lived experiences of people existing on the margins of society, a place where immigrants and refugees often find themselves existing. Specifically, intersectionality highlights ways in which “social divisions are constructed and intermeshed with one another in specific historical conditions to contribute to the oppression” of certain groups (Oleson, 2011, p. 134). Many hail the usefulness of intersectionality as a methodological tool that allows researchers to explore the interacting effects of multiple identities (Weldon, 2006). For example, research could examine ways that an immigrant may make decisions based on several important aspects of her/his identity such as race, gender, social class position, religion, and nationality.

This theory has been used to explore immigrants’ economic success, their experience of internalized classism, and their power and access to resources (Ali, Fall, & Hoffman, 2012; Cole, 2009). Intersectionality may be a unifying theory that illuminates the immigrant experience in a way that increases understanding of the role of the larger society, informs the efforts of each community, and provides a framework for policy.

35.3 Family Theories: A New Direction for Research with Resettled Populations

The discourse about immigrant experiences has shifted over time from an emphasis on fairly simple group processes, such as a unidimensional model of assimilation from one culture to another, to complex individual processes, such as intersectionality. Processes that occur at the family level have been largely absent from this discussion.

As we have identified in this textbook, families play a key role in the goals, resources, coping processes, and choices of the resettlement process. Falicov (2005) described how family relationships and ethnic identity during resettlement are “not separate experiences, but they interact with and influence each other in adaptive or reactive ways” (p. 402). Parents, grandparents, siblings, and children all influence one another in their choices about what to retain from their original culture in individual and family life, as well as what to learn and adapt from the new culture. There are many theories within the family and social science fields that can address the complexities of immigrant families through the resettlement process. In this section, we identify several family theories and their application to immigrant families.

System Theory

General systems theory (Von Bertalanffy, 1950) assumes that a family must be understood as a whole. Each family is more than the sum of its parts; the family has characteristics, behavior patterns, and cycles beyond how individual family members might act on their own. Individual members and family subsystems are interdependent and have mutual influence. This theory assumes that studying one member is insufficient to understand the family system. In order to assess patterns of adjustment in immigrant families, we must look both at the structure of the family unit and the processes that occur within that family system. For example, one study collected data from both parents and children in Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families in order to assess the role of family processes in clashes over cultural values. The researchers found that cultural clashes were linked to parent-child conflict, which in turn was linked to reduced parent-child bonding, both of which increase adolescent behavioral problems (Choi, He, & Harachi, 2008). This demonstrates one family pattern related to resettlement that can only be understood at the family system level.

Previous frameworks (e.g., structural functionalism) assumed that families always sought to maintain homeostasis (or “stick to the status quo”). General systems theory was the first to address how change occurs within families by acknowledging that although families often seek to maintain homeostasis, they will also promote change away from homeostasis. Systems such as families also have tendencies towards change (morphogenesis) or stability (morphostasis) and for families resettling in a new country and making decisions on what to preserve and how to adapt, there is a balance of the two. Families are able to examine their own processes and to set deliberate goals. Change occurs as the family system acknowledges that a particular family pattern is dysfunctional and identifies new processes that support their goals. Resettlement is one example of a large change that a family system could choose or be forced to make.

Human Ecology Framework

The human ecology framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) assumes that families interact within multiple environments that mutually influence each other. These environments include the biophysical (personal variables), the microsystem (the systems in immediate surroundings, such as family, neighborhood, church, work, or school), the mesosystem (the ways these immediate systems connect, such as the relationships between family and work), the exosystem (the larger social system, such as the stress of another family member’s job), and the macrosystem (the cultural values and the larger social system, such as immigrant and immigration policy that influences admission and social system access). In the context of a refugee family, a family might be influenced by the biophysical (e.g., whether or not members were injured as they fled the persecution), their microsystem (e.g., parental conflict while fleeing), their mesosystem (e.g., teachers and school personnel who are struggling with their own trauma from fleeing conflict and thus their ability to provide robust services is impaired), the exosystem (e.g., local leaders who do not consult with women living in shelters regarding their resources needs and don’t provide feminine hygiene products or children’s toys), and countless other environments (examples adapted from Hoffman & Kruczek, 2011). The family may have access to and be able to directly influence the mesosystem and at the same time feel powerless to make changes in the exosystem. Each of these environments will contribute to their coping.

With its focus on interaction with multiple environments, s the human ecology framework is an incredibly useful lens to employ cross-cultural contexts such as when considering immigrant families. For example, a researcher could ask, “How do Hmong immigrant families manage financial resources in their new environment in the United States?” and “How did Hmong families manage their financial resources while still living in Laos?” The assumptions and central concepts of human ecology theory would apply equally in either culture. The needs, values, and environment would be sensitively identified within each culture (See Solheim & Yang, 2010).

Additionally, human ecology theory assumes that families are intentional in their decision-making, and that they work towards biological sustenance, economic maintenance, and psychosocial function. As patterns in the social environment are more and more threatening to the family’s quality of life in these three areas, the system will be more and more likely to seek change, possibly by a move to a new country. The family system has certain needs, including physical needs for resources and interpersonal needs for relationships. If their current situation is not meeting these needs, the family system will engage in management to meet these needs within their value system.

The double ABC-X model (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983) describes the impact of crises on a family. It states that the combination of stressors (A), the family’s resources (B), and the family’s definition of the event (C) will produce the family’s experience of a crisis (X). The family’s multiple environments inform each component of the model, consistent with the human ecology framework. The double ABC-X suggests that there are multiple paths of recovery following a crisis, and these paths will be determined by the family’s resources and coping processes, both personal and external.

This model is relevant to immigrant and refugee families, as all of these families go through a significant transition in the process of resettlement. Whether or not this transition, or the events that precipitate it, are interpreted as crises will depend on the family’s other stressors (such as employment, housing, and healthcare availability and family conflict), resources (such as socioeconomic resources, family support, and access to community resources), and family meaning making (such as cultural and family values surrounding the decision).

Resilience Framework

The family resilience framework (Walsh, 2003) highlights the ways families withstand and rebound from adversity. Families cope together through their shared belief systems (such as making meaning of their situation, promoting hope, and finding spiritual strength) and family organization (flexible structure, cohesion, and social and economic resources). This framework also draws from the Carter and McGoldrick (1999) family lifecycle model to describe how families transition through stages and major life events, with specific vulnerabilities and resilience factors at each stage. Research that uses the resilience framework with immigrant and refugee families can highlight families’ strengths and identify the ways they thrive through challenges. Chapter 8 is an excellent example of how this framework applies to immigrant and refugee families.

Ambiguous Loss Theory

The family theories listed above can apply broadly to immigrant and refugee families of all backgrounds. Many immigrant and refugee families have a shared background of loss and trauma, and there are family theories that specifically can address these contexts. Ambiguous loss theory (Boss, 2006) describes the ambiguity that immigrant families can feel when they are separated, when family members are physically absent but psychologically very present. This ambiguity and separation can lead to great distress (See Solheim, Zaid, & Ballard, 2015). For a greater description of this theory in immigrant and refugee families, please see Chapter 2 and Chapter 5.

Video

Sunny Chanthanouvong, Executive Director, Lao Assistance Center of Minnesota, discusses cultural differences and perspectives between Lao children and parents (0:00-2:28).

35.4 Critical Theories

Critical theories offer an important contribution to the conceptualization of immigrant and refugee families. These theories assume that thought is mediated by power relationships, which are both socially and historically constructed (Kincheloe, McLaren, & Steinberg, 2011). They focus both on the individual’s experience and on how that experience developed through interactions with multiple environments (consistent with the human ecology framework; Chase, 2011; Olesen, 2011). Critical theories have emerged from a variety of disciplinary fields and with profound influence in the social sciences. Most prominently, feminist theory, queer theory, and critical race theory have challenged dominant discourses of social interactions. Researchers who operate from these critical approaches are committed to challenging constructed social divisions, and to acknowledging how structural mechanisms produce inequalities (Chase, 2011; McDowell & Shi Ruei, 2007; Olesen, 2011).

Critical theories are important lenses to employ in research with immigrant and refugee families specifically because they aim to amplify marginalized voices. Critical researchers actively look for the silent or subjugated voices, and seek to facilitate volume. Because immigrant and refugee groups are often marginalized within the new host culture, researchers can use critical research approaches to collaboratively advocate for these communities.

35.5 Cultural Values to Consider in Resettlement Research

Family theories hold promise for assessing the complex web of factors that influence family resettlement processes. As students, researchers, and/or clinicians, we must consider the values represented by the theories we choose to use. We offer several considerations as you evaluate potential theories.

In general, past and current ideas about the resettlement process place great responsibility for resettlement on the immigrants and their families. These ideas are grounded in the viewpoint that because these individuals and families choose to migrate, often to improve their life prospects, they should be held accountable for their success. However, underlying this viewpoint is a cultural bias towards personal responsibility and self-reliance. Although sometimes well-meaning, it can be at odds with different beliefs and practices held by immigrant communities. The bias towards personal responsibility and self-reliance is rooted in ideals of meritocracy that is widely accepted in the (commonly labeled) individualistic United States society. Meritocracy assumes that success and material possession results from an individual’s hard work and initiative within a fair and just society, and thus all privilege is attributed to one’s own hard work (Case, 2013). The argument against placing some responsibility on the larger society for the successful resettlement of immigrants emerges from the possible cultural incompatibility with this individualistic, capitalistic way of life. Most immigrant families arrive with hopes for achieving a better life and are prepared to continue to make sacrifices and work hard to do so. However, adapting to a new context with no frame of reference, little ability to communicate, and scarce resources may be a daunting task without external help.

Immigrants have described their experiences of loss and disruption, which is magnified when they are visible minorities in their receiving country (Abbott, Wong, Williams, Au, & Young, 2005). In-depth studies with immigrant men and women reported that almost all initial interactions they had with members of the dominant group were experienced as condescending with messages of superiority and discrimination (Muwanguzi & Musambira, 2012). One very direct way that local community receptions and perceptions can negatively impact resettlement experiences for immigrants is parent-school involvement and immigrant children’s scholastic achievement. Studies have consistently shown that parent school involvement for immigrant families has been low (Kao, 1995, 2004; Nord & Griffin, 1999; Turney & Kao, 2009). Kwon (2006) found that Korean immigrant mothers felt disempowered in their role and involvement with the school system, specifically related to their identity, cultural differences, and English skills. Focusing solely on conventional ways of parental involvement can overlook and underestimate immigrant parent strengths and efforts to support their children academically (Tiwana, 2012). In sum, the assumptions and expectations from commonly held values, when not critically analyzed, can act as barriers to immigrant families’ abilities to thrive in a new society.

Videos

True Thao, MSW, LICSW describes best practices for working with immigrant and refugee families (0:00-1:44).

True Thao discusses children’s and parents’ perspectives on migration and culture (0:00-2:42).

35.6 Future Directions

It is crucial that researchers use a theoretical framework that appropriately positions immigrant individuals and families within a “historical, political and socioeconomic context that accounts for their experiences” when supporting these populations (Domenech-Rodriguez & Wieling, 2004, p. 8). Interventionists, policymakers, and researchers must adopt a multidimensional approach to understanding resettlement processes. There are contraindications for applying generalizations to diverse groups and research is limited when it focuses on outcomes that may be myopic. Exploring the multiple intersecting identities of each individual and the engendering experiences of oppression is one way to move beyond a one-dimensional understanding of an immigrant’s experience. Additionally, utilizing a family lens to assess the impact of family resettlement is another important step in developing a comprehensive understanding of immigrant and refugee communities. Moreover, prevention and intervention programs designed to address longstanding health, economic, and social disparities within these families cannot be effectively implemented without careful consideration of the family and the complexities of their resettlement experiences.

35.7 End-of-Chapter

Immigrant resettlement is a complex topic, requiring the consideration of historical perspectives of intergroup relations, the interactive and non-linear nature of acculturation, the contextual elements of a state’s and nation’s socio-eco-political situations, and a deep introspection of the philosophies guiding our stance. Research continues to lack a clear understanding of resettlement efforts, particularly the processes within families. Creativity and flexibility is needed to reach a level of sophistication in our research and intervention to meet the needs of the increasingly diverse population in the United States. Intersectionality and family theories offer useful lenses for studying and understanding complex immigrant experiences; they can also inform practical strategies and policies to support successful immigrant resettlement.

Case Study

Nadia moved to the United States to get her BA in Psychology 12 years ago. When she met her partner (Adbul) in college, it was an easy decision to get married and apply for her citizenship. She was raised in Indonesia, while her husband was a second-generation immigrant from Saudi Arabia and shared her religious faith as a Muslim. Despite their shared faith, her husband’s family had initially expressed concern, and some even overtly expressing displeasure of his choice to marry her. After they were married, she continued to feel the pressure to meet certain expectations from her new family, which felt incongruent with her own culture and self. The one thing that seemed particularly important to her parents-in-law was that she begin wearing the hijab (traditional Muslim head covering). She had never been opposed to the idea and thus chose to wear it. After starting to wear the hijab, she noticed a positive change in the way people in her and Abdul’s religious community treated her. She felt more accepted and respected. She often reflects on how different her parents had raised her from her husband’s parents; back in Indonesia, her parents were not particularly wealthy, she remembered growing up alongside peers from different ethnicities and religions, and they practiced their religion with less restriction from both outside their religious group and within. Abdul, while raised in the United States seemed to be less open to making connections and forging relationships with others outside of his parent’s religious community. He often asked how he could be more accepting when others were not accepting of him.

Within the academic setting, Nadia felt confident in how well she was able to ‘adapt’ to the learning community. She spoke English well as her second language and presented in a very professional way. She was told by her faculty advisor, after deciding to start wearing a hijab that she would ‘have it easier’ if she did not. She graduated with a masters in Nursing and began to apply for jobs. She was offered many jobs but chose to accept one in a hospital in Oklahoma because it was the only job in the specialization that she wanted to pursue and also was somewhat relieved to be able to build her life with her husband on their own. Abdul was not particularly happy to move away from his family especially when he heard one of his cousins comment about how ‘small’ of a man he was to follow his wife around while she worked on her career, but similarly, he felt that forging a life away from his family may have some value. Additionally, he worked in a large tech company with branches nationwide and could transfer to the office in Tulsa.

Nadia and Abdul moved into their lovely new home in a suburb. She had felt eyes on her as they were unloading the moving truck and decided to walk over to her new neighbors to introduce herself. She convinced Abdul that this would be a good idea. No one answered the first door she knocked even though she was sure she remembered seeing them come home. Her other neighbor was very pleasant however she noticed that she made efforts to avoid eye contact with her and her husband.

Nadia was shocked at one her first experiences while training at her new job when a patient exclaimed loudly to their family after she left their room that it was a shame that the hospital employed a person ‘like that’. Additionally, almost all of her coworkers didn’t ever seem to want to have lunch with her. Abdul also was taken aback when upon presenting for his first workday his immediate supervisor asked him to list out all his qualifications and training when this seemed strange for a job transfer. Nadia began to fear whether relocating was the right choice.

When asked about her resettlement as an immigrant, Nadia would explain it as a complex journey, where her identities as woman, person of color, and foreign-born individual, including her religious affiliation, were integral. How Nadia is perceived, and what expectations are placed on her within the different spheres of her life contributes to how she would continue to construct her own identity and then choose to interact with these external contexts. Her family’s values of openness and flexibility that have allowed her to interact successfully in her academic context may be at odds with her partner’s strong boundaries with others and her experiences in her new milieu. She may not talk about acculturating or it being a progression towards assimilation, and in various relationships and contexts in her life, she may not even have similar goals for integrating. It may make sense to her to think about intersections, both of her identities and how her identities intersect with her partners’ identities and the different contexts she is in. Getting the sense that her neighbor felt some discomfort interacting with her as an immigrant woman of color, with an accent, wearing a hijab, and in a marriage relationship with a Muslim man, (albeit based on possible erroneous assumptions) is Nadia’s unique experience because of the identities that she appears and/or does inhabit. Thus in discussing resettlement as a social, familial, and individual process, Nadia’s resettlement is informed by these complex experiences.

Discussion Questions

- How have ideas about immigrant resettlement shifted through the years?

- How could the use of a family theory in future research add to our understanding of resettlement?

- Using the ABC-X model, identify the stressors, resources, and definition of the problem associated with Nadia and Abdul’s move to Oklahoma. Do you think they would consider it a crisis?

- What about Nadia’s story would stand out to you if you looked at it from the systems lens? From an assimilation lens? From an intersectionality lens?

References

Abbott, M. W., Wong, S., Williams, M., Au, M. K., & Young, W. (2000). Recent Chinese migrants’ health, adjustment to life in New Zealand and primary health care utilization. Disability and Rehabilitation 22(1/2): 43–56.

Alba, R. (1999). Immigration and the American realities of assimilation and multiculturalism. Sociological Forum, 14(1), 3-25.

Alba, R., & Nee, V. (2009). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Alexander, J. C. (2001). Theorizing the “Modes of incorporation”: Assimilation, hyphenation, and multiculturalism as varieties of civil participation. Sociological Theory, 19(3), 237-249.

Ali, S. R., Fall, K., & Hoffman, T. (2012). Life without work: Understanding social class changes and unemployment through theoretical integration. Journal of Career Assessment, 1, 1-16.

Anthias, F. (2001). The concept of social division and theorising social stratification: Looking at ethnicity and class. Sociology, 35(4), 835-854.

Anthias, F., & Yuval-Davis, N. (2005). Racialized boundaries: Race, nation, gender, colour and class and the anti-racist struggle. New York: Routledge.

Berg, J. A. (2010), Race, class, gender, and social space: Using an Intersectional approach to study immigration attitudes. The Sociological Quarterly, 51, 278–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2010.01172.x

Bernal, M. E. (1993). Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. NY: SuNY Press.

Berry. J.W. (1990). Psychology of acculturation. In J. Berman (Ed.), Cross-cultural perspectives: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (pp. OI-234). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 5-34.

Berry, J. W., Kim. U., Minde, T., & Mok, D. (1987). Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International Migration Review, 21, 491-51.

Boss, P. (2006). Loss, Trauma, and Resilience. New York: W.W. Norton.

Boyd, M. (2002). Educational attainment of immigrant offspring: Success or segmented assimilation. International Migration Review, 36:1037–60.

Bradley, H. (1996). Fractured identities: Changing patterns of inequality. Polity.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments in nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carter, B., & McGoldrick, M. (1999). The expanded family life-cycle: Individual, family, and social perspectives (3rd ed.). Needham Hill: Allyn & Bacon.

Case, K. (2013). Deconstructing privilege: Teaching and learning as allies in the classroom. New York: Routledge.

Chase, S. E. (2011). Narrative Inquiry: Still a field in the making. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 421-434). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Choi, Y., He, M., & Harachi, T.W. (2008). Intergenerational cultural dissonance, family conflict, parent-child bonding, and youth antisocial behaviors among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(1), 85-96.

Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: social norms, conformity, and compliance. In Ed. D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, G. Lindzey, The Handbook of Social Psychology (4th ed.), 151–92. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Influence: Science and Practice, 4th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64, 170–180. doi:10.1037/a0014564

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracial politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 140, 139-167.

Danso, R. (1999). Hosting the ‘Unwanted’ Guests: Public Reaction and Print Media Portrayal of Cross- border Migration in the New South Africa. Paper presented at the annual conference of the Canadian Association of African Studies. Lennoxville, Québec, June 7.

Danso R., & Grant, M., (2000). Access to housing as an adaptive strategy for immigrant groups: Africans in Calgary. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 32(3): 19–43.

Demos, V., & Lemelle, A. J. (2006). Introduction: Race, gender, and class for what. Race, Gender, and Class, 13(3/4), 4-15.

Domenech-Rodríguez, M., & Wieling, E. (2004). Developing culturally appropriate, evidence-based treatments for interventions with ethnic minority populations. In Voices of color: First person accounts of ethnic minority therapists (313-333).

Esses, V. M., Dovidio, J. F., Jackson, L. M., & Armstrong, T. L. (2001). The immigration dilemma: The role of perceived group competition, ethnic prejudice, and national identity. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 389-412.

Falicov, C. J. (2005). Emotional transnationalism and family identities. Family Process, 44, 399-406.

Farver, J. A. M., Narang, S. K., & Bhadha, B. R. (2002). East meets west: ethnic identity, acculturation, and conflict in Asian Indian families. Journal of Family Psychology, 16(3), 338.

Glazer, N. (1993). Is assimilation dead? The annals of the American academy of political and social science, 530(1), 122-136.

Gordon, M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion and national origins. Oxford University Press.

Gottfried, H. (2000). Compromising positions: emergent neo-Fordisms and embedded gender contracts. The British Journal of Sociology, 51(2), 235-259.

Hoffman, M. A., & Kruczek, T. (2011). A bioecological model of mass trauma: individual, community, and societal effects. The Counseling Psychologist, 39(8), 1087-1127. doi: 10.1177/0011000010397932

Kao, G. (1995). Asian Americans as model minorities? A look at their academic performance. American Journal of Education, 103, 121–159.

Kao, G. (2004). Parental influences on the educational outcomes of immigrant youth. International Migration Review, 38, 427–450.

Kazal, R. A. (1995). Revisting assimilation: The rise, fall, and reappraisal of a concept in American ethnic history. American Historical Review, 100(2), 437-471.

Kincheloe, J. L., McLaren, P., & Steinberg, S. (2011). Critical pedagogy and qualitative research: Moving to the bricolage. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 163-178). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kwon, Y. J. (2012). Empowerment/disempowerment issues in immigrant parents’ school involvement experiences in their children’s schooling: Korean immigrant mothers’ perceptions. Doctoral dissertation, University of Texas at Austin. Available from https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/ETD-UT-2012-05-5742

Lazarus. R.S. & Folkman. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer.

McCubbin, H. I., & Patterson, J. M. (1983). The family stress process: The Double ABCX Model of family adjustment and adaptation. In H. I. McCubbin, M. Sussman, & J. M. Patterson (Eds.), Social stress and the family: Advances and developments in family stress theory and research (pp. 7–37). New York: Haworth.

Modood, T., Berthoud, R., Lakey, J., Nazroo, J., Smith, P., Virdee, S., & Beishon, S. (1997). Ethnic minorities in Britain: diversity and disadvantage (No. 843). Policy Studies Institute.

Muwanguzi, S., & Musambira, G. W. (2012). Communication experiences of Ugandan immigrants during acculturation to the United States. Journal of Intercultural Communication. Available from: http://immi.se/intercultural/nr30/muwanguzi.html

Nord, C. W., & Griffin, J. A. (1999). Educational profile of 3- to 8- year-old children of immigrants. In D. J. Hernandez (Ed.), Children of immigrants: Health, adjustment, and public assistance (pp. 91–131). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Olesen, V. (2011). Feminist qualitative research in the millenium’s first decade: Developments, challenges, prospects. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 129-146). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Passel, J., & Cohn, D. (2009, April 14). A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States. Pew Hispanic Center – Chronicling Latinos Diverse Experiences in a Changing America. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2009/04/14/a-portrait-of-unauthorized-immigrants-in-the-united-states/

Park, R. E. (1928). Human migration and the marginal man. American Journal of Sociology, 33. 881-893.

Park, R. E., Burgess, E. W., & McKenzie, R. D. (1925). The City. University of Chicago Press, 1, 925.

Phinney, J. S. (1991). Ethnic identity and self-esteem: A review and integration. Hispanic journal of behavioral sciences, 13(2), 193-208.

Phinney, J. S., Horenczyk, G., Liebkind, K., & Vedder, P. (2001). Ethnic identity, immigration, and well‐being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 493-510.

Pollert, A. (1996). Gender and class revisited; or, the poverty of patriarchy. Sociology, 30(4), 639-659.

Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: segmented assimilation and its variants. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 530, 74–96.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkely, CA: University of California Press.

Rumbaut, R. G. (1994). The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review, 28(4), 748-794.

Sakamoto, I. (2007). A critical examination of immigrant acculturation: Toward an anti-oppressive social work model with immigrant adults in a pluralistic society. British Journal of Social Work, 37, 515–535. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcm024

Scholten, P. (2011). Framing immigrant integration: Dutch research-policy dialogues in comparative perspective. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Shields, S. A. (2008). Gender: An intersectionality perspective. Sex Roles, 59, 301–311.

Solheim, C. A., & Yang, P. N. D. (2010). Understanding generational differences in financial literacy in Hmong immigrant families. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 38(4), 435-454.

Solheim, C. A., *Zaid, S., & Ballard*, J. (2015). Ambiguous loss experienced by transnational Mexican immigrant families. Family Process. doi:10.1111/famp.12130

Telzer, E. H., & Garcia, H. A. V. (2009). Skin color and self-perceptions of immigrant and US-born Latinas: The moderating role of racial socialization and ethnic identity. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 31(3), 357-374.

Tiwana, R. K. (2012). Shared immigrant journeys and inspirational life lessons: Critical reflections on immigrant Punjabi Sikh mothers’ participation in their children’s schooling. UC Los Angeles Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Available from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/71z3v45z

Turney, K., & Kao, G. (2009): Barriers to school involvement: Are immigrant parents disadvantaged?, The Journal of Educational Research, 102(4), 257-271.

van Tubergen, F. (2006). Immigrant integration: A cross-national study. NY: LBF Scholarly Publishing LLC.

Viruell-Fuentes, E. A. (2007). Beyond acculturation: immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 65(7), 1524-1535.

Von Bertalanffy, L. (1950). An outline of general system theory. British Journal for the Philosophy of science.

Walsh, F. (2003). Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process, 42(1), 1-18.

Warner, W. L., & Srole, L. (1945). The social systems of American ethnic groups. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Waters, M. C., Van, V. C., Kasinitz, P., & Mollenkopf, J. H. (2010). Segmented assimilation revisited: types of acculturation and socioeconomic mobility in young adulthood. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33(7), 1168-1193.

Waters, M. C., & Jiménez, T. R. (2005). Assessing immigrant assimilation: New empirical and theoretical challenges. Annual review of sociology, 105-125.

Weber, L. (1998). A conceptual framework for understanding race, class, gender, and sexuality. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22(1), 13-32.

Weldon, S. L. (2006. The structure of intersectionality: A comparative politics of gender. Politics and Gender, 2(2), 235-248.

Xie, Y., & Greenman, E. (2010). The social context of assimilation: Testing implications of segmented assimilation theory. Social Science Research, 40, 965-984.

Attribution

Adapted from Chapters 1 through 9 from Immigrant and Refugee Families, 2nd Ed. by Jaime Ballard, Elizabeth Wieling, Catherine Solheim, and Lekie Dwanyen under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.