Chapter 25: Immigration & Immigrant Policy: Barriers & Opportunities for Families

Learning Objectives

- Learn from a national and global perspective on immigration and immigrant policy.

- Recognizing that the world is constantly and rapidly changing.

- Recognizing that Global/national/international events can have an impact on individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities.

- Global implications dictate that we foster international relationships and opportunities to address international concerns, needs, problems, and actions to improve the well-being of not only U.S. citizens, but global citizens.

25.1 Introduction

For Jose and Ester, it was painful to try to raise their two sons in El Salvador. The money they raised in a day was not enough to buy food for one family meal, and gang violence was everywhere. Jose decided to move to the United States to provide for his family. After 7 years, he saved enough to bring his wife to the United States, and they both started working long hours to save the money to bring their sons. They paid a coyote (someone who smuggles people across borders) $10,000, which covered 3 attempts to bring their sons to the United States. The first time, they were caught an hour after crossing into Mexico and sent home. The second time, they were caught by police in Mexico and held 3 days for ransom, and then continued north after the coyote paid. The boys were caught by immigration officials in Texas. They were held in detention for several days. With the help of an advocacy office, the boys flew to Baltimore to be reunited with their parents. (Story published by Public Radio International in 2014. Full story available from: http://www.pri.org/stories/2014-08-18/these-salvadorian-parents-detail-their-sons-harrowing-journey-meet-them-us).

Migration is most often motivated by a desire to improve life for families. The story of Jose and Ester has common elements with most stories of migration: families must make painful choices about whether moving to a new home and/or being separated from one another is necessary to provide for the family’s well-being. Families often feel “pushed” out of their home country by poor pay or job availability, political instability, or violence. They feel “pulled” to a new country by the promise of better pay to support their families, greater educational opportunities for their children, greater safety for their families, or the opportunity to be together again after a long absence.

Jose and Ester’s story has another common element with all stories of migration: their methods of migration and their opportunities to be reunited were influenced by immigration and immigrant policy. Immigration policy determines who enters the United States and in what numbers, while immigrant policy influences the integration of immigrants who are already in the United States (Fix & Passel, 1994). For Jose and Ester, their sons were not eligible to travel legally across the border due to current immigration policy restrictions and delays. Policy determines whether immigrants have access to employment, to health or educational resources, and to family reunification (Menjívar, 2012). It determines whether they or their family are within the law or outside it (Menjívar, 2012).

Immigration and immigrant policy has a rippling impact on all facets of society, and impacts both immigrants and those born in the United States. At the economic level, the job skills and education of incoming immigrants impact our labor market and shifts where job growth occurs in our economy. On a social level, we interact with immigrants as neighbors and friends, and as coworkers, employees, and supervisors.

There are many articles, books, and book chapters that discuss the intricacies of immigration and immigrant policy. The purpose of this chapter is to explore the impact of these policies on families.

We will describe the different groups invested in immigration and immigrant policy and the various viewpoints on what is most important to incorporate into policy. We will then describe the history of policy, and the current policies affecting families. We end by describing the current barriers and opportunities for families. Chapter 26 will address special policies and issues that apply to refugees specifically.

Immigrant Definitions

Immigrants are people who leave their country of origin to permanently settle in another country. They may enter the country legally and are therefore called documented immigrants or they may enter illegally and are referred to as undocumented immigrants.

Legal or documented immigrants. For the purposes of this chapter, legal immigrants are defined as individuals who were granted legal residence in the United States. This would include those from other countries who were granted asylum, admitted as refugees, admitted under a set of specific authorized temporary statuses for longer-term residence and work, or granted lawful permanent residence status or citizenship.

Illegal or undocumented immigrants. Illegal or undocumented immigrants are foreign-born non-citizens residing in the country who have not been granted a visa, or were not given access (i.e., inspected) by the Department of State upon entrance (US Visas, n.d.). They may have entered the country illegally (e.g., crossing the borders), or may have entered the country legally with a valid visa but have stayed beyond the visa’s expiration date. Other terms also used in immigration research include: unauthorized immigrants, undocumented immigrants, and illegal immigrants. However, in this chapter, “undocumented immigrant” will be used to reference illegal and unauthorized immigrants.

Jaime Ballard (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota), Damir Utržan (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota), Veronica Deenanath (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota), and Dung Mao (Family Social Science, University of Minnesota)

25.2 Immigration Policy

Purposes of Immigration Policy

There are five primary purposes of immigration policy (US English Foundation, 2016; Fix & Passel, 1994).

- Social: Unify citizens and legal residents with their families.

- Economic: Increase productivity and standard of living.

- Cultural: Encourage diversity, increasing pluralism, and a variety of skills.

- Moral: Promote and protect human rights, largely through protecting those feeling persecution.

- Security: Control undocumented immigration and protect national security.

Tug-of-War in Immigration Policy

There are many ideological differences among the stakeholders in immigration policy, and many different priorities. In order to meet the purposes listed above, policy-makers must balance the following goals against one another.

Provide refuge to all versus recruit the best. Some stakeholders desire to provide refuge for the displaced (Permanently stamped on the Statue of Liberty are the words, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”). These stakeholders seek to welcome all who are separated from their families or face economic, political, or safety concerns in their current locations. Others aim to recruit those best qualified to add to the economy.

Meet labor force needs versus protect current citizen employment. Immigrant workers are expected to make up 30-50% of the growth in the United States labor force in the coming decades (Lowell, Gelatt, & Batalova, 2006). In general, immigrants provide needed employment and do not impact the wages of the current workforce. However, there are situations (i.e., during economic downturns) where immigration can threaten the current work force’s conditions or wages.

Enforce policy versus minimize regulatory burden and intrusion on privacy. In order to enforce immigration policy away from the border, the government must access residents’ documents. However, this threatens citizens’ privacy. When employers are required to access these documents, it also increases regulatory burden for the employers.

Key Stakeholders in Policy

There are many groups who are deeply invested in immigration and immigrant policy; their fortunes rise or fall with the policies set. These groups are called “stakeholders.” Key stakeholders in immigration and immigrant policy in the United States include the federal government, state governments, voluntary agencies, employers, families, current workers, local communities, states, and the nation as a whole.

Families. As we described in the introduction, one of the most common motivations for immigration is to provide a better quality of life for one’s family, either by sending money to family in another country or by bringing family to the United States (Solheim, Rojas-Garcia, Olson, & Zuiker, 2012). Immigration policy impacts these families’ abilities to migrate to access safer living conditions and seek economic stability. Further, immigration policy impacts a family’s opportunity for reunification. Reunification means that immigrants with legal status in the United States can apply for visas to bring family members to join them. Approximately two-thirds of the immigrants in the United States were sponsored by family members who migrated first and became permanent residents (Kandel, 2014).

“My goals are to offer my family a decent life and economic stability, to guarantee them a future without serious problems, with a house, a means of transport… things that sometimes you can’t achieve in Mexico. Our goal must be for our family’s welfare, as much for my family here as for my family back there” – Mexican Immigrant, Solheim et al., 2012 p. 247.

Federal government. The federal government is currently solely responsible for the creation of immigration policies (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2004). In the past, each state determined its own immigration policy according to the Articles of Confederation because it was unclear whether the United States Constitution gave the federal government power to regulate immigration (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2011). A series of Supreme Court cases beginning in the 1850s upheld the federal government’s right to create immigration policies, arguing that the federal government must have the power to exclude non-citizens to protect the national public interest (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2004). The Supreme Court has determined that the power to admit and to remove immigrants to the United States belongs solely to the federal government (using as precedents the uniform rule of Naturalization, Article 1.8.4, and the commerce clause, Article 1.8.3). In fact, there is no area where the legislative power of Congress is more complete (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2004).

Immigration responsibilities were originally housed in the Treasury Department and the Department of Labor, due to its connection to foreign commerce. In the 1940s, the immigration office (now called the “INS”) was moved to the United States Department of Justice due to its connection to protecting national public interest (USCIS, 2010). The federal departments and agencies that implement immigration laws and policies have changed significantly since the terrorist attacks of 2001. In 2001, the United States Commission on National Security created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which absorbed and assumed the duties of Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS).

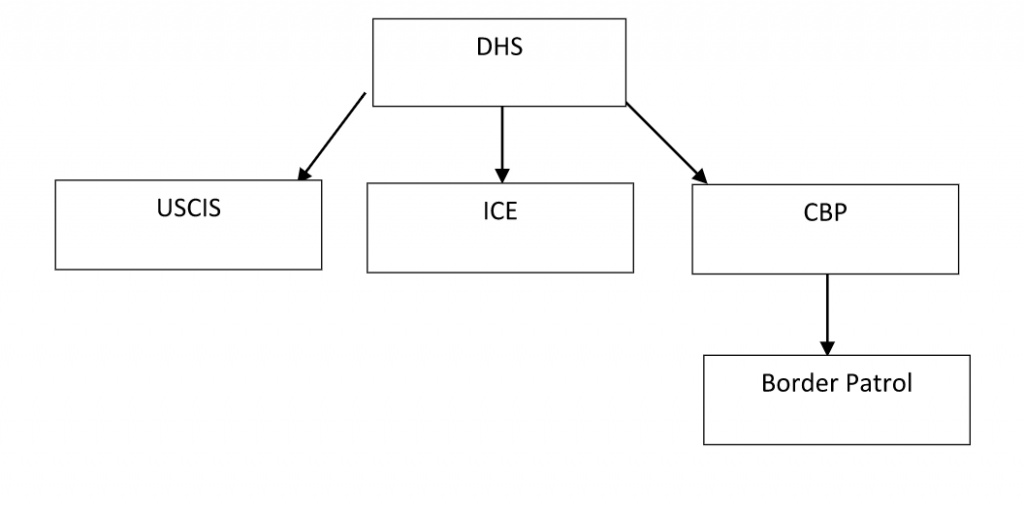

Three key agencies within DHS enforce immigration and immigrant policy (see Figure 1):

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS): USCIS provides immigration services, including processing immigrant visa requests, naturalization petitions, and asylum/refugee requests. Its offices are divided into four national regions: (1) Burlington, Vermont (Northeast); (2) Dallas, Texas (Central); (3) Laguna Niguel, California (West); and (4) Orlando, Florida (Southeast). The director of USCIS reports directly to the Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security. It is important to note that immigration officers, who traditionally hold law degrees, have broad discretion in deciding whether an application is complete and accurate (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2011).

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE): ICE is primarily tasked with enforcing immigration laws once immigrants are inside the United States’ ICE is responsible for identifying and fixing problems in the nation’s security. This is accomplished through five operational divisions: (1) immigration investigations; (2) detention and removal; (3) Federal Protective Service; (4) international affairs; and (5) intelligence.

- United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP): USCBP includes the Border Patrol, which is responsible for identifying and preventing undocumented aliens, terrorists, and weapons from entering the country. In addition to these responsibilities, USCBP is responsible for regulating customs and international trade to intercept drugs, illicit currency, fraudulent documents or products with intellectual property rights violations, and materials for quarantine.

State governments. Although states have no power to create immigration policy, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA, 1996) enabled the Secretary of Homeland Security to enter into agreements with states to implement the administration and enforcement of federal immigration laws. States are also responsible for policy regarding immigrant and refugee integration. There is wide variation in how states pursue integration. Not all policies are welcoming. For example, several have passed legislation that limits access of public services to undocumented immigrants (e.g., Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina, and Utah). In contrast, states such as Minnesota, have sought to expand immigrant access to public services. These drastically different approaches have promoted consideration of this critical important task at the federal level. In late 2014, President Obama formed the “White House Task Force on New Americans” whose primary purpose is to “create welcoming communities and fully integrating immigrants and refugees” (White House, 2014). This is the first time in United States history that the executive branch of the government has undertaken such an effort.

Employers. Employers have high stakes in policy that impact immigration, particularly as it impacts their available labor force. United States employers who recruit highly skilled workers from abroad typically sponsor their employees for permanent residence. Other employers who need a large labor force, particularly for low-skill work, often look to immigrants to fill positions.

Employers are also impacted by requirements to monitor the immigrant status of employees. Following the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986, it became illegal to knowingly employ undocumented immigrants. Many employers are now required by state law or federal contract to use the e-verify program to confirm that prospective employees are not undocumented immigrants. Such requirements aim to reduce incentives for undocumented immigration, but also pose burdens of liability and reduced labor availability for employers. The National Council of Farmer Cooperatives (2015) and the American Farm Bureau Federation oppose measures that could constrict immigration such as the E-Verify program, stating that it could have a detrimental impact on the country’s agriculture.

Current workforce. Overall, research demonstrates that immigration increases wages for United States-born workers (Ottaviano & Peri, 2008; Ottaviano & Peri, 2012; Cortes, 2008; Peri, 2010). Estimated increases in wages from immigration range from .1 to .6% (Borjas & Katz, 2007; Ottaviano & Peri, 2008; Shierholz, 2010). However, these wage increases are not unilaterally and consistently distributed across time, skill, and education levels of workers. Some researchers have found that low-education workers have experienced wage decreases due to immigration, as large as 4.8% (Borjas & Katz, 2007). However, other researchers have found that among those without a high school diploma, wages decreased by approximately 1% in the short-run (Shierholz, 2010; Ottaviano & Peri, 2012) but were increased slightly in the long run (Ottaviano & Peri, 2012).

Immigration generally does not decrease job opportunities for United States-born workers, and may slightly increase them (Peri, 2010). However, during economic downturns when job growth is slowed, immigration may have short-term negative effects on job availability and wages for the current workforce (Peri, 2010). Immigrants create growth in community businesses (see Textbox 1, “Did you know”). It is nonetheless important to emphasize that the fear of non-citizens taking away employment opportunities from citizens is a primary driver for immigration laws (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2011).

Communities. United States communities must provide education and health care regardless of immigration status (i.e., Plyer v. Doe, 1982). In areas with rapidly increasing numbers of immigrant workers and their families, this can tax local communities that are already overburdened (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006). The Congressional Budget Office found that most state and local governments provide services to unauthorized immigrants that cost more than those immigrants generate in taxes (2007). However, studies have found that immigrants may also infuse new growth in communities and sustain current levels of living for residents (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006).

Country. Immigrants provide many benefits at a national level. Overall, immigrants create more jobs than they fill, both through demand for goods and service and entrepreneurship. Foreign labor allows growth in the labor force and sustained standard of living (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006). Even though immigrants cost more in services than they provide in taxes at a state and local government level, immigrants pay far more in taxes than they cost in services at a national level. In particular, immigrants (both documented and undocumented) contribute billions more to Medicare through payroll taxes than they use in medical services (Zallman, Woolhandler, Himmelstein, Bor & McCormick, 2013). Additionally, many undocumented immigrants obtain social security cards that are not in their name and thereby contribute to social security, from which they will not be authorized to benefit. The Social security administration estimates that $12 billion dollars were paid into social security in 2010 alone (Goss et al., 2013).

Did you know?

While immigrants make up 16% of the labor force, they make up 18% of the business owners

Between 2000 and 2013, immigrants accounted for nearly half of overall growth of business ownership in the United States (Fiscal Policy Insitute, 2015).

25.3 Current Immigration Policy

Although the decision to migrate is generally made and motivated by families, immigration policy generally focuses on the individual. For example, visas are granted to individuals, not families. In this section, we will describe the immigration policies that are most influential for today’s families. For an overview of all immigration policies and their historical context, please see The History of Documented Immigration Policy (1850s-1920s, 1920s-1950s, 1950s to Present, and the History of Undocumented Immigration Policy, respectively).

In the landmark decision of Arizona et al. v. United States (2012), Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy remarked that “The history of the United States is in part made of the stories, talents, and lasting contributions of those who crossed oceans and deserts to come here.”

1952 McCarran-Walter Act: This act and its amendments remain the basic body of immigration law. It opened immigration to all countries, establishing quotas for each (US English Foundation, 2016). This act instituted a priority system for admitting family members of current citizens. Admission preference was given to spouses, children, and parents of U.S. citizens, as well as to skilled workers (Immigration History, 2019). This meant that more families from more countries had the opportunity to reunite in the United States.

1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act or Immigration and Nationality Act and 1978 Amendments. In this act, the national ethnicity quotas were repealed. Instead, a cap was set for each hemisphere. Once again, priority was given to family reunification and employment skills. This act also expanded the original four admission preferences to seven, adding: (5) siblings of United States citizens; (6) workers, skilled and unskilled, in occupations for which labor was in short supply in the United States; and (7) refugees from Communist-dominated countries or those affected by natural disasters. This expanded the opportunities for family members to reunite in the United States.

1990 Immigration Act. This act eased the limits on family-based immigration (US English Foundation, 2016). It ultimately led to a 40% increase in total admissions (Fix & Passel, 1994).

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. The Dream Act, first introduced in 2001, would allow for conditional permanent residency to immigrants who arrived in the United States as minors and have long-standing United States residency. While this bill has not yet been signed into law, the Obama administration created renewable two-year work permits for those who meet these standards. This had the largest impact on undocumented families. Many children travel to the United States without documents to be with their families, and then spend most of their lives in the United States. If the bill passed, these children would have new opportunities to pursue higher education and jobs in the land they think of as home, without fear of deportation. In 2017, the Trump administration attempted to rescind the DACA memorandum, but federal judges blocked the termination. Individuals with DACA can continue to renew their benefits, but first-time applicants are no longer accepted (American Immigration Council, 2019).

2000 Life Act and Section 245(i). This allowed undocumented immigrants present in the United Sttes to adjust their status to permanent resident, if they had family or employers to sponsor them (US English Foundation, 2016).

2001 Patriot Act: The sociopolitical climate after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks drastically changed immigrant policies in the United States. This act created Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS), greatly enhancing immigration enforcement.

2005 Bill. The House of Representatives passed a bill that increased enforcement at the borders, focusing on national security rather than family or economic influences (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006).

2006 Bill. The Senate passed a bill that expanded legal immigration, in order to decrease undocumented immigration (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006).

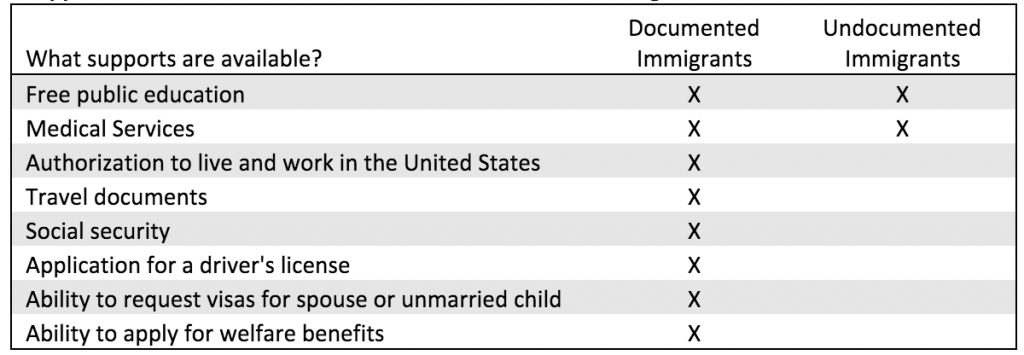

As these policies indicate, it is currently very difficult to enter the United States without documentation. There are few supports available to those who do make it across the border (see Table 1). However, the 2000 Life Act and the Dream Act provide some provisions for families who live in the United States to obtain documentation to remain together, at least temporarily.

For families who want to immigrate with documentation, current policy prioritizes family reunification. Visas are available for family members of current permanent residents, and there are no quotas on family reunification visas (See “Process for Becoming a Citizen). Even when family members of a current permanent resident are granted a visa, they are a long way from residency. They must wait for their priority date and process extensive paperwork. If a family wants to immigrate to the United States but does not have a family member who is a current permanent resident or a sponsoring employer, options for documented immigration are very limited.

Table 1

Supports available to documented and undocumented immigrants</strong

Textbox 2

Process of Becoming a Citizen, also called “Naturalization”

File a petition for an immigrant visa. The first step of documented immigration is obtaining an immigrant visa. There are a number of ways this can occur:

- For family members. A citizen or lawful permanent resident in the United States can file an immigrant visa petition for their immediate family members in other countries. In some cases, they can file a petition for a fiancé or adopted child.

- For sponsored employees. United States employers sometimes recruit skilled workers who will be hired for permanent jobs. These employers can file a visa petition for the workers.

- For immigrants from countries with low rates of immigration. The Diversity Visa Lottery program accepts applications from individuals in countries with low rates of immigration. These individuals can file an application, and visas are awarded based on random selection.

If prospective immigrants do not fall into one of these categories, their avenues for documented immigration are quite limited. For prospective immigrants who fall within one of these categories, their petition must be approved by USCIS and consular officers. However, they are still a long way from residency.

Wait for priority date. There is an annual limit to the number of available visas in most categories. Petitions are filed chronologically, and each prospective immigrant is given a “priority date.” The prospective immigrant must then wait until there is an available visa, based on their priority date.

Process paperwork. While waiting for the priority date, prospective immigrants can begin to process the paperwork. They must pay processing fees, submit a visa application form, and compile extensive additional documentation (such as evidence of income, proof of relationship, proof of United States status, birth certificates, military records, etc.) They must then complete an interview at the United States. Embassy or Consulate and complete a medical exam. Once all of these steps are complete, the prospective immigrant received an immigrant visa. They can travel to the United States with a green card and enter as a lawful permanent resident (US Visas, n.d.).

A lawful permanent resident is entitled to many of the supports of legal residents, including free public education, authorization to work in the United States, and travel documents to leave and return to the United States (Refugee Council USA, 2019). However, permanent resident aliens remain citizens of their home country, must maintain residence in the United States in order to maintain their status, must renew their status every 10 years, and cannot vote in federal elections (USCIS, 2015).

Apply for citizenship. Generally, immigrants are eligible to apply for citizenship when they have been a permanent resident for at least five years, or three years if they are married to a citizen. Prospective citizens must complete an application, be fingerprinted, and have a background check, complete an interview with a USCIS officer, and take an English and civics test. They must then take an Oath of Allegiance (USCIS, 2012).

25.4 Opportunities & Barriers for Immigrant Families

The United States gives priority to family reunification and has made great efforts to make the process of reunification accessible to immigrants. This provides new opportunities and security for immigrant families. However, there are still substantial challenges and barriers to families. In the sections below, we will describe the opportunities and barriers available to families in different configurations, including families seeking reunification, families living together in the United States without documentation, and couples in international marriages.

Reunification

As we outlined in the policy section, United States policy prioritizes family reunification, and immigrant and refugees’ spouses and children are eligible to immigrate without visa quotas. The majority of current immigrants are family members being reunited with United States citizens or permanent residents.

In addition to these policies that promote family reunification, there are now more accepting policies to support reunification of gay citizens and their immigrant spouses. Historically, United States immigration policy has denied immigration to same-sex orientation applicants. Under the 1917 Immigration Act, homosexuality was grounds for exclusion from immigration. In 1965, Congress argued that gay immigrants were included in a ban on “sexual deviation” (Dunton, 2012). The ban against gay immigrants continued until 1990, when the Immigration and National Act was amended, removing the homosexual exclusion. Moreover, asylum has been granted for persecution due to sexual orientation (Dunton, 2012). Until 2013, immigrants and refugees could apply for residency or visas for their opposite-sex spouses. There was no provision made for same-sex partners. Following the overturn of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), citizens and permanent residents can now sponsor their same-sex spouses for visas. United States citizens can also sponsor a same-sex fiancé for a visa (USCIS, 2014).

Despite these advances, there are two large challenges faced by immigrants seeking reunification. First, it requires substantial time and resources, including legal counsel, to navigate the visa system. Adults can petition for permanent resident visas for themselves and their minor children, but processing such applications can take years. Currently, children of permanent residents can face seven-year wait times to be accepted as legal immigrants (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006).

In some cases, children can age out of eligibility by the time the application is processed and the visa is granted. Such children then go to the end of the waiting list for adult visa processing (Brown, 2014). The 2002 Child Status Protection Act is designed to protect children against aging out of visa eligibility when the child is the primary applicant for a visa, but the act does not state if it applies if a parent was applying on behalf of their family (Brown, 2014). In the 2014 ruling to Cuellar de Osorio v. Mayorkas, the Supreme Court found that the child status protection act does not apply for children when a parent is applying on behalf of their family. Such young adults have already generally been separated from family for many years, and will now be separated for years or decades more.

Undocumented Families

For families who do not have a sponsoring family member, have a sponsoring employer, or originate from a country with few immigrants, the options for legal immigration to the United States are very limited. Those families who choose to travel to the United States face substantial barriers, including a perilous trip across the border, few resources, and the constant threat of deportation.

One of the most dangerous times for undocumented families is the risky trip across the border. In order to avoid border patrol, undocumented immigrants take very dangerous routes across the United States border. The vast majority of all apprehensions of undocumented immigrants are on the border (while the remainder is apprehended through interior enforcement). For example, in 2014 ICE conducted 315,943 removals, 67% of which were apprehended at the border (nearly always by the Border Patrol), and 33% of which were apprehended in the interior (ICE, 2019). The trip and efforts to avoid Border Patrol can be physically dangerous and in some cases, deadly. The acronym ICE symbolizes the fear that immigrants feel about capture and deportation. A deportee in Exile Nation: The Plastic People (2014), a documentary that follows United States deportees in Tijuana, Mexico, stated that ICE was chosen as the acronym for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency because it “freezes the blood of the most vulnerable.” The Trump administration instituted a policy of separating families apprehended at the border and of criminal prosecution for all apprehended crossing the border illegally, including those applying for asylum. More than 2,600 children were separated from their caregivers under this policy, which was later overturned.

Even after arrival at the interior of the United States, undocumented immigrants feel stress and anxiety relating to the fear of deportation by ICE (Chavez et al., 2012). This impacts their daily life activities. Undocumented parents sometimes fear interacting with school, health care systems, and police, for fear of revealing their own undocumented status (Chavez et al., 2012; Menjivar, 2012). They may also avoid driving, as they are not eligible for a driver’s license.

Since 2014, the Department of Homeland Security has placed a new emphasis on deporting undocumented immigrants. Department efforts generally prioritize apprehending convicted criminals and threats to public safety, but recent operations have taken a broader approach. In the opening weeks of 2016, ICE coordinated a nationwide operation to apprehend and deport undocumented adults who entered the country with their children, taking 121 people into custody in a single weekend. The majority of these individuals were families who applied for asylum, but whose cases were denied. Similar enforcement operations are planned (DHS press office, 2016). In many cases, the parents’ largest concern is that immigration enforcement will break up the family. Over 5,000 children have been turned over to the foster care system when parents were deported or detained. This can occur in three ways:

- when parents are taken into custody by ICE, the child welfare system can reassign custody rights for the child,

- when a parent is accused of child abuse or neglect and there are simultaneous custody and deportation proceedings, and

- when a parent who already has a case open in a child welfare system is detained or deported (Enriquez, 2015; Rogerson, 2012).

“One of my greatest fears right now is for anybody to take me away from my baby, and that I cannot provide for my baby. Growing up as a child without a father [as I did], it’s very painful… I felt like there was no male to protect them.” – Mexican Immigrant describing how his fear of deportation grew after his baby daughter was born (Enriquez, 2015, p. 944)

Although the perilous trip and threat of deportation are significant challenges for undocumented immigrant families, there are two recent policy changes that offer new opportunities and protections for undocumented families. First, some states have sought to expand the educational supports available to undocumented immigrants. The State of Minnesota, for example, enacted the “Dream Act” into law (2013). This unique act, which is also known as the “Minnesota Prosperity Act,” makes undocumented students eligible for State financial aid (State of Minnesota, 2014; Chapter 99, Article 4, Section 1).

Second, there are now greater protections for unaccompanied children. In some cases, children travel across the border alone, without their families. They may be travelling to join parents already in the United States, or their parents may send them ahead to try to obtain greater opportunities for them. As a result of human rights activism, unaccompanied and separated immigrant children are now placed in a child welfare framework by licensed facilities under the care of the Office of Refugee Replacement (Somers, 2011). They provide for education, health care, and psychological support until they can be released to family or a community (Somers, 2011). Each year, 8,000 unaccompanied immigrant children receive care from the ORR (Somers, 2011).

Mixed Status Families

Some members of the family may have documentation, while others do not. There may be cases where a United States citizen has applied for a visa for his family members, but they live without documentation while they wait for their priority date. Alternatively, there may be children who are born in the United States to undocumented parents. These children are entitled to benefits that their undocumented parents are not, such as welfare benefits (Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2005).

Children are subject to “multigenerational punishment,” where they are disadvantaged because of their parents’ undocumented status (Enriquez, 2015). As in undocumented families, parents fear interacting with school, health care, or police (Chavez et al., 2012; Menjivar, 2012). These children have limited opportunities to travel domestically (due to risks of driving without a license) or internationally (due to lack of travel papers) (Enriquez, 2015). When parents’ employment opportunities are limited due to their lack of documentation, the children share in the economic instability (Enriquez, 2015).

“I’m still [supposed to be] perceived as this male provider… [but] we lost our place [after my job found out about my status], and now I’m [living] with my in-laws, and it’s hard to find a great-paying job… It makes you feel like [people are saying]. ‘How dare you do that to a little child.’ It’s hard because you do feel guilty, you feel that you’re punishing someone that shouldn’t be punished.” –Mexican immigrant (Enriquez, 2015, p. 949)

International Marriages

In our increasingly global world, more couples are meeting and courting across national borders. Many of these couples ultimately seek to live together in the same country. In some cases, an immigrant travels to the United States and obtains citizenship, but still hopes to marry someone from their home country and culture. Under current United States policy, there are visas available for fiancés to immigrate to the United States. However, these relationships are screened. There are strict requirements to prove that the marriage is “bonafide.” If a marriage is considered “fraudulent,” the immigrant spouse can be detained and the native spouse can be fined. There are also limits to how many fiancé visas can be filed within a certain time frame so that the same person cannot repeatedly apply for a fiancé visa with different partners (USCIS, 2005).

Regulations are in place to protect the non-citizen fiancés. In some cases, the United States citizen has much greater power than the non-citizen fiancé and may exploit their lack of knowledge of English, local customs, and culture. The United States Government is required to give non-citizen fiancés information about their rights and resources, in an effort to prevent or intervene in cases of intimate partner violence (USCIS, 2005). A citizen can use an international marriage broker (IMB) to connect with a partner from their home country or another desired country. The International Marriage Broker Regulation Act of 2005 (IMBRA) states that the government must conduct criminal background checks on prospective citizen clients, in order to protect the welfare of the fiancés who will enter the United States (USCIS, 2005).

Video

Ruben Parra-Cardona, Ph.D., LMFT discusses mixtures of hope and discrimination in the United States (10:48-11:53).

25.5 Future Directions

There are two shifts in immigration policy that are critical for the well-being of families. First, policy should shift to accelerate family reunification for those families whose visas have been accepted. Families are currently separated from their children for years, caught in a holding pattern of waiting. This leads to stress, grief, and difficulty building relationships during key developmental times in a child’s life. Accelerating processing applications and shorter wait times would facilitate greater family well-being.

Second, policy could provide greater protection for vulnerable children in undocumented or mixed-status families. In cases where a parent is deported, the child’s welfare should be carefully considered in whether to leave the child in the care of a local caregiver or provide the option to send the child to the home country with their parent.

Recent Policy Changes and the Impact on Families

Malina Her

Since his presidential campaign, President Trump and his administration has placed immense attention on immigration policies. As a result, many recent policy changes and efforts related to immigration enforcement and refugee resettlement have greatly impacted immigrant and refugee families (Pierce, 2019). We highlight here two key policies, the lowering of the refugee admissions cap, and the introduction of new vetting requirements.

Lowering of the refugee admissions

Since the creation of the U.S. refugee resettlement program in 1980, the annual admission of refugees has hit an all-time low within the fiscal year of 2019 with a ceiling cap of 30,000 admissions. Yet the actual refugee admissions and arrivals are even lower, with only 12,154 actual admissions being granted within the first 6 months of the fiscal year (Meissner & Gelatt, 2019; Pierce, 2019). This policy change directly affects the possibility of family reunification, especially in families where partners are not legally married (Solis, 2019).

New vetting requirements

The Trump administration has introduced new vetting requirements for refugees, citing national security risk as a primary reason. This expansion of vetting has increased the amount of information needed for visa applications, such as providing prior years of travel or even usernames to social media accounts (Pierce, Bolter, & Selee, 2018). In addition, resettlement applications of refugees from 11 countries perceived as “high risk” to national security have been reduced on the priority list (Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Mali, North Korea, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria and Yemen). Yet reports by the National Counterterrorism Center in 2017 have shown that terrorists are unlikely to use resettlement programs as a means to enter the United States (Meissner & Gelatt, 2019; Pierce, 2019). A former director of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services agrees that the increased vetting requirements of refugees appears unnecessary as the vetting procedures in place are already rigorous enough to identify any potentially problematic applicant (Rodriguez, 2017).

These policies have implications for both our communities and for individual refugee families. A draft report conducted by the Health and Human Services in the summer of 2017 found that between 2005 and 2014, refugees contributed an estimated amount of $269.1 billion dollars in revenues to the U.S. government (Davis & Sengupta, 2017), income that may be stemmed by the low admissions ceiling and longer processing times due to increased vetting procedures. for refugee families, these new vetting procedures add to the long waiting times for family reunification as it backlogs cases. Family members have to wait longer as they undergo and complete additional requirements and it prolongs their cases such that delays can amount to decades. For some, reunification becomes nearly impossible (Hooper & Salant, 2018). Furthermore, applicants seeking refuge or asylum from countries on the high-risk list are turned away from immediate protection as their applications continue to float in the system for review of any potential security risk. Thus many may have to stay in a country where they continue to face violence and persecution as they wait.

25.6 End-of-Chapter Summary

Though there are substantial barriers to family reunification and well-being, there are also great opportunities. In recent decades, U.S. policy has been gradually changed to be more inclusive and aimed more intensely on family reunification. The case studies below outline different paths to immigration and family reunification. They demonstrate the opportunities and assistance which are available, as well as the challenges faced.

Case Study 1: Becoming a Citizen

Mr. and Mrs. Addisu, both in their early 70s, immigrated to the United States from Ethiopia nearly 15 years ago with sponsorship from their daughter and her United States-born husband. The couple was eager to learn English and embrace the different cultural values, which meant becoming citizens. They wanted to join the country that their child and grandchildren called home.

After filing the appropriate documentation, paying related fees, and waiting for several years, both Mr. and Mrs. Addisu were scheduled for their naturalization test. The Addisu’s daughter helped them study the material. They particularly hoped that their parents could obtain citizenship so that the Addisus could take a long trip home to see their friends in Ethiopia, which they had not been able to do since moving to the United States with strict residency requirements.

But it quickly became apparent that Mr. Addisu had trouble learning English, which was primarily age-related. With assistance from a local church, Mr. Addisu applied for an English Language Exemption. This enabled him to exempt from the English language requirement and take the civics test in Oromo with the assistance of an interpreter.

Case Study 2: Family Reunification

Matias, a United States citizen, filed a petition to request a green card for his daughter Victoria who still lived in Mexico. Victoria had a 15-year old son and a 14-year daughter, who were listed on the petition as “derivative beneficiaries”, eligible to receive a visa if their mother received one. Their petition was approved, and they waited for their priority date. Victoria and her son and daughter continued living in Mexico, they lived on a low income and in a violent neighborhood. They communicated regularly with Matias, and Victoria repeatedly expressed how excited she was to see her dad again, and to be able to provide a better life for her kids. She regularly checked on her application and the priority date, excited for its arrival.

The priority date arrived 7 years later. Victoria’s children were now 22 and 21, and so they were no longer eligible to be derivative beneficiaries on Victoria’s visa. When Victoria learned, she was distraught. She talked to every advocacy group she could find, but there were no options. There would have been services available to expedite their petition as the children approached adulthood, but she and Matias had been unaware.

Victoria talked with her children about the options; they could all remain together in Mexico, or she could travel to the United States and apply for them to join her. One of her children as now working, and the other was attending a technical school. They decided together that it would be best for Victoria to go on to the United States. Once she arrived and became a lawful permanent resident, she filed a petition for her kids to get a visa. It was approved. Once again, the family waited for their priority date. Now, Victoria was with her father, but separated from her kids. It was now her kids she was calling, saying, “I miss you, I am excited to see you, I hope we can be together soon, soon, soon.” After 8 years, the priority date arrived. Victoria’s children, now ages 29 and 30, joined their mother in the United States.

Discussion Questions

- Think back on your own family history. If you had family immigrate to the United States, what policies were in place when they arrived?

- What would motivate a family to immigrate without documentation? What might make them decide against it?

- What challenges does a child face if their parents do not have documentation?

- What are the arguments for making family reunification quicker and more accessible? What are the arguments against it?

- What barriers did the families in the case studies have to reunification? What supports did they receive?

Helpful Links

Migration Policy Institute

- http://www.migrationpolicy.org/

- The Migration Policy Institute is “an independent, nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank in Washington, DC dedicated to analysis of the movement of people worldwide”. They have regular publications and press releases about trends in migration, both to the United States and internationally.

Statue of Liberty Oral History

- https://www.statueofliberty.org/discover/stories-and-oral-histories/

- The Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation, Inc. keeps a database of oral histories of immigrants who came through Ellis Island during their migration to America between 1892 to 1954.

References

American Civil Liberties Union. (2019). Family separation by the numbers. Retrieved from: https://www.aclu.org/issues/immigrants-rights/immigrants-rights-and-detention/family-separation

American Immigration Council. (2019). The Dream Act, DACA, and Other Policies Designed to Protect Dreamers. Retrieved from: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/dream-act-daca-and-other-policies-designed-protect-dreamers

Borjas, G. J., & Katz, L. F. (2007). The evolution of the Mexican-born workforce in the United States. National Bureau of Economic research: Mexican immigration to the United States. Retrieved from: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c0098.pdf

Brown, K. J. (2014). The long journey home: Cuellar de Osario v. Mayorkas and the importance of meaningful judicial review in protecting immigrant rights. Boston College Journal Of Law & Social Justice, 34(3), 1-13.

Chavez, J. M., Lopez, A., Englebrecht, C. M., & Viramontez Anguiano, R. P. (2012). Sufren Los Niños: Exploring the Impact of Unauthorized Immigration Status on Children’s Well-Being Sufren Los Niños: Exploring the Impact of Unauthorized Immigration Status on Children’s Well-Being. Family Court Review, 50(4), 638-649. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2012.01482.x

Chishti, M. & Bolter, J. (2018). Family separation and zero-tolerance policies rolled out to stem unwanted migrants but may face challenges. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/family-separation-and-zero-tolerance-policies-rolled-out-stem-unwanted-migrants-may-face

Congressional Budget Office. (2007). The impact of unauthorized immigrants on the budgets of state and local governments. Retrieved from: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/110th-congress-2007-2008/reports/12-6-immigration.pdf

Cortes, (2008). The effect of low-skilled immigration on U.S. prices: Evidence from CPI data. Journal of Political Economy, 116(3), p. doi: 0022-3808/2008/11603-0004.

Davis, J. H., & Sengupta, S. (2017). Trump administration rejects study showing positive impact of refugees. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/18/us/politics/refugees-revenue-cost-report-trump.html

Department of Homeland Security Press Office. (2016). Statement by Secretary Jeh C. Johnson on Southwest Border Security[Press release]. Retrieved from: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2016/03/09/statement-secretary-jeh-c-johnson-southwest-border-security

Dunton, E. S. (2012). Same sex, different rights: Amending U.S. immigration law to recognize same-sex partners of refugees and asylees. Family Court Review, 50(2), 357-371. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2012.01441.x

Enriquez, L. E. (2015). Multigenerational punishment: Shared experiences of undocumented immigration status within mixed-status families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 939-953. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12196

Fiscal Policy Institute. 2015. How immigrant small businesses help local economies grow. Retrieved from http://fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Bringing-Vitality-to-Main-Street.pdf.

Fix, M. E. & Passel, J. S. (1994). Immigration and immigrants: Setting the record straight. Urban Institute. Retrieved from: http://www.urban.org/publications/305184.html#II

Garner, B.A. (Ed.). (2014). Black’s law dictionary. Eagan, MN: West Publishing.

Goss, S., Wade, A., Skirvin, J.P., Morris, M., Bye, D. M., & Huston, D. (2013) Effects of Unauthorized Immigration on the Actuarial Status of the Social Security Trust Funds. Acturial Note No. 151. Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary.

Hooper, K., & Salant, B. (2018). It’s relative: A cross-country comparison of family-migration policies and flows. MPI: Issue Brief, 1-20.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). (2019). Fiscal Year 2018 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report. Retrieved from https://www.ice.gov/features/ERO-2018Immigration History. (2019). Immigration and nationality act of 1962 (The McCarran-Walter Act). Retrieved from: https://immigrationhistory.org/item/immigration-and-nationality-act-the-mccarran-walter-act/

Immigration History. (2019). Immigration and nationality act of 1962 (The McCarran-Walter Act). Retrieved from: https://immigrationhistory.org/item/immigration-and-nationality-act-the-mccarran-walter-act/

Kandel, W. A. (2014). U.S. family-based immigration policy. Congressional Research Service Report for Congress. Retrieved from: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R43145.pdf

Krogstad, J. M. (2019). Key facts about refugees to the U.S. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/07/key-facts-about-refugees-to-the-u-s/

Lowell, B. L., Gelatt, J., & Batalova, J. (2006). Immigrants and labor force trends: The future, past, and present. Insight, 17. Retrieved from: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/immigrants-and-labor-force-trends-future-past-and-present

Mandeel, E. W. (2014). The Bracero program 1942-1964. American international Journal of Contemporary Research, 4(1), p. 171-184. Retrieved from: http://www.aijcrnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_1_January_2014/17.pdf

Meissner, D., & Gelatt, J. (2019). Eight key U.S. immigration policy issues: State of play and unanswered questions. MPI: U.S. Immigration Policy Program, 1-34.

Meissner, D., Meyers, D. W., Papademetriou, D. G., & Fix, M. (2006). Immigration and America’s Future: A new chapter. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/immigration-and-americas-future-new-chapter

Menjívar, C. (2012). Transnational Parenting and Immigration Law: Central Americans in the United States. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies, 38(2), 301-322. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2011.646423

Nadadur, R. (2009). Illegal immigration: A positive economic contribution to the United States. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35(6), doi: 10.1080/13691830902057775

National Council of Farmer Cooperatives. (2019). E-verify. Retrieved from: http://ncfc.org/build/issues/labor-and-infrastructure/e-verify/

Ottaviano, G. I. P., & Peri, G. (2012). Rethinking the effect of immigration on wages. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10, 152-197.

Ottaviano, G., & Peri, G. (2008). Immigration and National Wages: Clarifying the Theory and the Empirics. NBER Working Papers, 14188. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge Ma.

Peri, G. (2010). The impact of immigrants in recession and economic expansion. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/impact-immigrants-recession-and-economic-expansion

Pierce, S. (2019). Immigration-related policy changes in the first two years of the Trump administration. Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/immigration-policy-changes-two-years-trump-administration

Pierce, S., Bolter, J., & Selee, A. (2018). U.S. immigration policy under Trump: Deep changes and lasting impacts. MPI: Transatlantic Council on Migration, 1-24.

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2005). US immigration policy and recent immigration trends. Retrieved from: http://www.iie.com/publications/chapters_preview/4000/02iie4000.pdf

Rodriguez, L. (2017, November). I used to run the immigration service-and Trump’s refugee policy is baseless. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/11/vetting-refugees-trump/544430/

Rogerson, S. (2012). Unintended and Unavoidable: The Failure to Protect Rule and Its Consequences for Undocumented Parents and Their Children. Family Court Review, 50(4), 580-593. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2012.01477.x

Shierholz, H. (2010). Immigration and Wages: Methodological Advancements Confirm Modest Gains for Native Workers. Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper #255.

Solheim, C.A., Rojas-Garcia, G., Olson, P.D., & Zuiker, V.S. (March/April, 2012). Family Influences on Goals, Remittance Use, and Settlement of Mexican Immigrant Agricultural Workers in Minnesota. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 43(2).

Solis, S. (2019, October). “My kids need me”: Congolese family among thousands potentially affected by U.S. refugee cap. Mass Live. Retrieved from https://www.masslive.com/politics/2019/10/my-kids-need-me-congolese-family-among-thousands-potentially-affected-by-us-refugee-cap.html

Somers, A. (2011). Voice, agency and vulnerability: The immigration of children through systems of protection and enforcement. International Migration, 49(5), 3-14.

US Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2005). Information on the legal rights available to immigrant victims of domestic violence in the United States and facts about immigrating on a marriage-based visa. Retrieved from: http://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Humanitarian/Battered

%20Spouse%2C%20Children%20%26%20Parents/IMBRA%20Pamphlet%

20Final%2001-07-2011%20for%20Web%20Posting.pdf

US Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2010). Welcome to the United States: A Guide for New Immigrants. Retrieved from: http://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/files/nativedocuments/M-618.pdf

US Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2012). A guide to Naturalization. Retrieved from: http://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/files/article/M-476.pdf

US English Foundation, Inc. (2016). American immigration – An overview. Retrieved from: https://usefoundation.org/research/issues/american-immigration-overview/

U.S. Visas. (n.d.). The Immigrant Visa Process. Retrieved from: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/immigrate/the-immigrant-visa-process.html

Weissbrodt, D., & Danielson, L. (2004). The source and scope of the federal power to regulate immigration and naturalization. University of Minnesota Human Rights Library. Retrieved from: http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/immigrationlaw/chapter2.html

Weissbrodt, D. & Danielson, L. (2011). Immigration law and procedure in a nut shell (6th ed.). Eagan, MN: West Publishing Company.

White House. (2014). Presidential memorandum: Creating welcoming communities and fully integrating immigrants and refugees. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/11/21/presidential-memorandum-creating-welcoming-communities-and-fully-integra

Zallman, L., Woolhandler, S., Himmelstein, D., Bor, D., & McCormick, D. (2013). Immigrants contributed an estimated $115.2 billion more to the Medicare trust fund than they took out in 2002-2009. Health Affairs, 32(6), 1153-1160. Doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1223

27.7 Appendices

Appendix 1

History of Documented Immigration Policy: the Qualitative Restrictions Phase (1850s to 1920s)

In the mid-1800s, the United States began a phase of qualitative restrictions. There was a labor shortage during the 1840s, and many Chinese men and families had immigrated to fill this gap. During the recession that followed, stigma against the Chinese grew. Western states complained that wages were lowering due to Chinese immigration. Immigration policy during this time aimed to exclude “undesirable” immigrants based on country of origin (notably China), skills, and criminal background.

- 1868 14th Amendment: This amendment granted citizenship rights to all people born in the United States. Not all immigrants were considered equally eligible, however; aliens of African descent were eligible for naturalization, while Asians were not (US English Foundation, 2016).

- The Act of 1882: This act is considered the first federal immigration act, which barred (1) convicts; (2) prostitutes; (3) lunatics; (4) idiots; and (5) those likely to become public charges (dependent for support) from immigrating.

- 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act: Immigration of all Chinese laborers was banned. Current Chinese immigrants were denied naturalization, and undocumented immigrants could now be deported (Fix & Passel, 1994). The ban was not repealed until 1943 (US English Foundation, 2016).

- 1881: This Act added the (1) diseased; (2) paupers,” and “polygamists” to the list of people excluded from immigrating to the United States.

- 1903: And this act added (1) epileptics; (2) insane; (3) beggars; and (4) anarchists.

- 1906 Naturalization Act: Naturalization required the ability to speak and understand English (US English Foundation, 2016). This was implemented in an effort to discourage “inferior” immigrants from applying (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2011).

- 1917 Immigration Act or Asiatic Barred Zone Act: Congress barred immigrants from most of Asia (US English Foundation, 2016). They also added a literacy test for naturalization and banned immigrants with “perceived mental inferiority”, which included homosexuality (Dunton, 2012).

Appendix 2

History of Documented Immigration Policy: the Quantitative Restrictions Phase (1920s to 1950s)

In the early 1900s, the United States began a phase of quantitative immigration restrictions. The United States was again in a recession, and citizens feared that immigrants could reduce employment opportunities. Immigration policy now instituted quotas to restrict immigration.

- 1921 Quota law: Each national origin was given a quota limit. For example, immigrants from each European country could not exceed 3% of the national census of people from that country currently living in the United States. Quotas favored western and northern Europeans, and most Asian countries continued to be excluded (US English Foundation, 2016).

- 1924 Immigration and Naturalization Act, also known as Johnson-Reed Act: This restricted the annual quota to 2% for each country, substantially reducing total immigration. The system favored Southern and Eastern European immigrants, and immigrants from most Asian countries were prohibited (US English Foundation, 2016).

- 1952 McCarran-Walter Act: This act, and the amendments below, remains the basic body of immigration law. It opened immigration for many countries, establishing quotas for all countries (US English Foundation, 2016). It also established a quota for immigrants whose skills were needed in the labor force (Fix & Passel, 1994). The act also implemented a four admission preferences: (1) unmarried adult sons and daughters of United States citizens; (2) spouses and unmarried sons and daughters of United States citizens; (3) professionals, scientists, and artists of exceptional ability; and (4) married adult sons and daughters of United States citizens.

Appendix 3

History of Documented Immigration Policy: the Inclusive Phase (1950s to Present)

President Kennedy denounced the national origins quota system (“Immigrant policy should be generous; it should be fair; it should be flexible. With such a policy we can turn the world, and our own past, with clean hands and a clear conscience.”). The civil rights movement gave further additional power to a more inclusionary policy system. Immigration policy began to eliminate racial, national, and ethnic biases (Fix & Passel, 1994).

- 1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act or Immigration and Nationality Act and 1978 Amendments. In this act, the national ethnicity quotas were repealed. Instead, a cap was set for each hemisphere. Priority was given to family reunification and employment skills. This shifted away from a priority on European Immigration (Fix & Passel, 2004), and led to a substantial increase in documented immigration (Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2005). This act also expanded the original four admission preferences to seven, adding: (5) siblings of United States citizens; (6) workers, skilled and unskilled, in occupations for which labor was in short supply in the United States; and (7) refugees from Communist-dominated countries or those affected by natural disasters.

- 1990 Immigration Act: This act increased the ceiling for employment-based immigration and eased the limits on family-based immigration (US English Foundation, 2016). It was created as a compromise between exclusionary and inclusionary policies (see undocumented immigration section below), but ultimately led to a 40% increase in total admissions (Fix & Passel, 1994). It also created a Diversity Immigrant Visa Program, known as the “Green Card Lottery,” increasing the focus on diversity in admissions. Each year, the Attorney General issues visas through this program to regions that sent few immigrants to the United States.

- 2000 Legal Immigration Family Equity (LIFE) Act: This act temporarily revived a section of the Immigration Act, allowing qualified immigrants to obtain permanent residency, even if they entered without documents.

- 2001 Patriot Act: This act allowed for the indefinite detention of immigrants

- Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals: The Dream Act, proposed in the Senate in 2001, would allow for conditional permanent residency to immigrants who arrived in the US as minors and have long-standing US residency. While this bill has not been signed into law, the Obama administration has created renewable two-year work permits for those who meet these standards.

Appendix 4

History of Undocumented Immigration Policy

Before the mid-1900s, there were few policies that regulated the identification and deportation of undocumented immigrants. The Immigration Act of 1891 introduced undocumented immigration policy by establishing the Bureau of immigration, responsible for deportation of undocumented immigrants. In 1940, the Alien Registration Act allowed for all previously undocumented immigrants to obtain legal recognition. All residents who were not US citizens were required to register with the government. They were given a receipt card (AR-3) as proof of compliance. After World War II, this became part of the immigration procedure. Immigrants were now given a visitors form, temporary foreign laborer card, or a permanent resident card (“green card”; US English Foundation, 2016).

Policies became much more stringent beginning in the mid-1900s. Immigration rates dropped during the Great Depression resulting in a labor shortage. The government established the Bracero program in 1942 to actively recruit temporary agricultural laborers from Mexico. Over 4 million Mexican laborers were recruited over the next twenty years (Mandeel, 2014). Through this program, Mexican immigrants began to establish homes and social networks in the United States, and in turn, helped friends and family to come to the United States both legally and illegally.

There was controversy over the Bracero program. As a result, the INS implemented “Operation Wetback” that targeted and deported Mexican immigrants between 1954 and 1964. When the Bracero program ended in 1964, there was an influx in undocumented immigration (Mandeel, 2014; Nadadur, 2009). Legislation after this point has aimed to reduce undocumented immigration.

- 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act: This act was implemented in response to criticism of the United States being unable to control the flow of undocumented immigrants. The act made it illegal to hire undocumented workers, and created sanctions. It required that states verify immigration status of applicants for welfare (Fix & Passel, 1994). It expanded border enforcement (Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2005; Fix & Passel, 1994). These provisions were meant to reduce enticements to immigrate without documentation and to enforce immigration policy. However, it also granted amnesty to all people living without documents prior to 1982, and to their immediate families in other countries (US English Foundation, 2016). This led to the legalization of more than one percent of the United States population (Fix & Passel, 1994). In order to reduce financial burdens of this declaration of amnesty, the act also provided funds for states to provide health care, public assistance, and English education (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006), but barred most previously undocumented immigrants from receiving federal public welfare assistance for five years (Weissbrodt & Danielson, 2011).

- 1996 Undocumented Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act: This act aimed to reduce undocumented immigration. It reduced benefits for legal immigrants, such as food stamps and welfare. It increased border control and expedited deportation of undocumented immigrants and increased required documentation for employment (US English Foundation, 2016).

- 1996 Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act: This act expedited the removal of foreigners convicted of felonies, or who do not have proper documentation. The felony bar remains today and is an important determinant of immigrants being deported, even if they arrived in the United States legally.

- 2000 Life Act and Section 245(i): This allowed undocumented immigrants present in the United States to adjust their status to permanent resident, if they had family or employers to sponsor them (US English Foundation, 2016).

- 2001 Patriot Act: The sociopolitical climate post-September 11, 2001 drastically changed immigrant policies in the United States. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was formed in 2002 and absorbed Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS). This act created two other agencies: Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS). This act also enhanced immigration enforcement and barred immigrants with potential terrorist links (US English Foundation, 2016).

- 2005: The House of Representatives passed a bill that increased enforcement at the borders, focusing on national security rather than family or economic influences (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006).

- 2005 REAL ID Act: This act required that before states issue a driver’s license or identification care, they must verify the applicant’s legal status.

- 2006: The Senate passed a bill that expanded legal immigration, in order to decrease undocumented immigration (Meissner, Meyers, Papademetriou & Fix, 2006).

Attribution

Adapted from Chapters 1 through 9 from Immigrant and Refugee Families, 2nd Ed. by Jaime Ballard, Elizabeth Wieling, Catherine Solheim, and Lekie Dwanyen under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.