6 Showcasing Your Artifacts: Show and Tell What You Know

Lynn Meade

Making the Case for Your Credibility

Imagine you are a lawyer making a case for why a person is credible. You stand before the judge and the jury, and you describe the person and the things they have done. You show evidence to support your case. Just as a skilled lawyer meticulously assembles evidence to establish the credibility of their client, a portfolio serves as your compelling evidence, demonstrating your worthiness to be considered trustworthy and knowledgeable. Within these carefully curated artifacts lies the power to not only show that you attended classes, but that you actively absorbed and applied valuable knowledge.

An artifact, in this context, becomes the cornerstone of your credibility. You use it to prove to others what you know and why you can be trusted. It serves as tangible proof of your accumulated learning, practical experiences, and ambitions. Your portfolio is a way that you can tell your story. Whether you wish to highlight your creativity, your adeptness at forging intricate connections, or any other trait, the artifacts you choose are your storytellers.

In the same way, a lawyer doesn’t merely present evidence, but meticulously explains its relevance; presenting an artifact isn’t enough. It must be accompanied by your thoughtful reflection. You need to explain why your artifact matters. Never assume your audience will inherently grasp the connection; spell it out for them. If your story is that you are creative, then show artifacts that demonstrate your creativity and explain to them your creative process. If your story is that you can make complex connections, then show artifacts that support that story and write about how you brought the pieces together.

In this chapter, you will learn about artifacts and how to collect, select, reflect, and connect your artifacts. You will learn to consider lessons learned from leisure and will be asked to explore any high-impact practices you have engaged in. Your portfolio is not merely a process of assembling artifacts; it is a journey of self-discovery, purposeful selection, thoughtful reflection, and intentional connection.

Artifacts

Artifacts are evidence of what you have learned. They are used to demonstrate skills, show evidence of learning, document experiences, and showcase competencies. Artifacts typically are accompanied by a reflection to help your audience make connections. Look at the chart below for ideas and examples of artifacts used in portfolios.

Writing

- Essays

- Science -based research paper

- Research papers

- Journal entries

Grant - Art analysis

- Scientific Analysis Paper

- Blogs

- Reports

- Lesson plans

- Grant proposals

- Scientific Writing -Children’s Book

- Case studies

- Research proposal

- Technical review of scientific literature

- Thesis or Dissertation

- Literature Review

- Worksheet to teach a concept

- Research Philosophy

Videos

- Film

- YouTube Videos

- Teaching collages

- Speeches

- Performance videos

- Lectures

- Video Shorts

- Nonverbal conducting video

- Classroom video projects

- Recordings of classroom projects

- Slide show

- Conducting videos

- Video about an athlete’s story from the media page

Visuals

- Photos showing you working

- Photos of artistic accomplishments

- Photos showing you doing research

- Graphic design work

- Drawings

- Scanned art projects

- Posters

- Paintings

- Three-Dimensional Art Projects

- Slideshow of your projects

- Digital projects

- Flow charts

- Flyers of programs you attended

Audio Recording

- Sound Cloud files

- Podcasts-Built for Earth

Podcast-Mosquito Control - Musical recording

- Recitals

- Vocal tracks

- Musical arrangements

Assignments

- Group projects

- Spreadsheet analysis for teachers

- Presentation slides

- Sample lesson plans

- Capstone project

- Web page mock-up

- Journal presentation

- Specialized items for teaching artifacts

- Engineering capstone course

Scientific Reports

- Lab reports

- Lab work and collaboration

- Mathematical proofs

- Workflow chart for project

- Research poster

- Schematics

- Math Paper

- Data visualization

- Petri net data analysis

- Research poster -example 2

Business Applications

- Spreadsheets

- Financial reports

- Marketing Plan

- Marketing Research Report

- Leadership Development Plan and Speech

- Strengths Quest, Strength Deployment Inventory

Proof of Credentials

- Awards

- Certifications

- Digital badges

- Press releases about achievements

- News articles about you

- Scholarship/fellowship award letters

- Memberships

- Posts about your work

Special Projects

- Internships

- Internship-veterinary clinic

- Study abroad-Internship

- Products from fellowship projects

- Volunteer experiences

- Service learning

- Campus group

- Social media posts

Many of these have links to examples for you to see how it looks in someone’s portfolio. It is important to realize that every college and every class has different reasons and expectations for what should accompany an artifact. Be sure to check with your teacher regarding expectations around captioning and writing reflections for artifacts.

Four-Step Process: Collect, Select, Reflect, and Connect

Now that you know what an artifact is, you need to start gathering and making sense of your artifacts. This is a four-step process: collect, select, reflect, and connect.

1. Collect

As we already discussed, it is important to collect things to include in your portfolio. Create a computer file of itrems that shows your learning. Include anything that you can show to build the case for your competency. Don’t only show things that are perfect examples, but also include some things that tell a story of personal growth. In the collection phase, you want to have many things from which to choose.

2. Select

Once you have a collection of artifacts to pick from, start sorting through them to find ones that can best tell your story. You are looking for meaningful evidence to support the case that you are credible. As with all things in a portfolio, you should determine your audience and your purpose. You should always ask yourself, why am I writing this portfolio and who will look at it? If you are applying to a graduate school that values writing, it will be important to showcase your research papers. If you are applying to be a teacher, you will provide your lesson plans as evidence. If you are applying to work as a curator of art, you will want to show your art projects.

Questions to ask yourself in the selection phase:

How does this artifact illustrate your brand?

Why will it matter to your portfolio’s audience?

How will you present this artifact to be engaging for viewers in your portfolio?

Does this artifact advance the story that you are telling about your abilities?

3. Reflect

After you have selected your artifact, you need to write about what it means. This means writing a narrative reflection using the what, so what, now what process. In this step, the goal is to describe your artifact and how your interaction with it has transformed you.

There is an entire chapter dedicated to writing detailed and meaningful reflections: Reflective Expression: Documenting Growth and Learning.

Examples

- Check out how Lea Bourgade highlights an artifact. In the portfolio they demonstrate the use of a Halo Sport product for a neuroscience experiment involving a violin. (It is as interesting as it sounds.) This is a great illustration of reflecting on an internship, using a YouTube video as an artifact, and writing a well-thought-out reflection that answers the what, so what, and now what.

- Look at how Maggie Engler uses the what, so what, and now what to reflect on a class project.

Ask yourself, “What did I learn by looking at these artifact examples?”

4. Connect

In the connect phase, you connect your artifact to the audience who will read about it and you write in a way that forwards your purpose. You want to highlight how this artifact links to the larger picture of who you are and what you want.

-

Examples

Notice in this example from Sydney Maples that she answers the what, so what, and now what questions. The last paragraph also links what she has learned to other things she is doing.

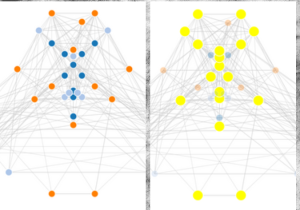

Sydney Maples’ Artifact The Introduction to Science Communication class that I took allowed me to blend my interest in neuroscience and computer programming. In addition, it gave me the opportunity to practice my science communication abilities through a variety of different genres, ranging from short-form articles to full literature reviews. For my final project, I was allowed to present on a scientific topic using any style or medium, and I chose to create a visual brain in a Javascript platform using the d3 library, in order to visualize which regions of the brain are affected by specific disorders.

The two images on the side reflect a sample output of the application. The image on the left presents a picture of the landing page before a brain disorder is selected by the user. The image on the right is a picture of the nodes (represented by brain regions) of the brain, with the highlighted nodes representing the relevant regions to the brain disorder selected. The highlighted nodes are clickable, and selecting a node allows you to read more about the role that the brain region plays in the respective brain disorder. I intentionally designed this such that each network had a different color, providing an appendix (not pictured) that describes the general function of each brain network.Though I had had a small bit of experience with Javascript in a previous class, this class was (indirectly) my first “real” introduction, and I owe that to the independent nature of the project. Working on this project also showed me how compatible all the fields I am interested in can be together, and, more importantly, how they can overlap. Sydney Maples

Turn Leisure Activities into Career Lessons

Many people overlook the benefit of leisure activities in building career confidence. In many settings, you may decide to include them if you can connect them to meaningful life lessons. Consider artifacts that you can display to draw attention to these activities. Xavier Smith, Career Counselor at the University of Arkansas often helps students write about and talk about leisure activities as valuable experiences so I asked him to share his ideas:

Throughout college, you may engage in several activities that you would consider to be leisurely such as intramurals, Greek life, or RSOs like yearbook. You do those things out of enjoyment, not necessarily for monetary gain or prestige. Additionally, you may find in college that some of your most impactful learning takes place outside of the classroom in times of leisure. You may not see it initially, but there are many workplace skills that you can learn in leisure activities skills such as communication, teamwork, use of technology, professionalism, networking, and the list continues. You could consider skills as currency. Skills determine how much you’re worth to a company which ultimately may affect how much you may earn, or even negotiate. Skills are massively important to the flexibility and trajectory of your career. So, let’s talk about the types of skills you are developing.

Let me provide you with an example. Toward the end of my undergraduate career, I rediscovered an old pastime of roller skating. I decided to transition from skating with blades to quads to learn a new version of skating. The process was very taxing mentally and physically because I had a fear of falling. I did not want to embarrass myself in front of others. One day a man in his seventies skated past me with style and stopped nearby to tell me that if I was not willing to fall then I was not prepared to learn the be an advanced skater. I had to get over myself to get better. This taught me the importance of failure to inform the master of a task. It taught me the perseverance to persist in past initial frustration to achieve a goal. In the process, I learned how to teach others to skate which also translated to me learning how to communicate. Roller skating was my leisure and it informed the development of workplace skills.

- What lessons have you received from a leisure activity that can translate to the workplace?

- How would you describe the skills you developed?

- As a result of the leisure activity, who did I meet?

- How can I use the skills in other settings?

- What skills did I learn or use?

- What did I do that translates to a career skill?

- What did I learn about myself?

By highlighting the skills acquired through seemingly recreational pursuits, you can better understand your own capabilities, enhance your marketability, and navigate your career paths with a heightened sense of self-awareness and purpose.

Experiences Valued By Employers: Include Them If You Can

Some experiences carry a lot of weight with employers. Experiences where you have had an opportunity to apply what you have learned such as internships, work-study, community projects, and collaborative research may elevate you as a job candidate.

Take a look at the chart below from the Association of American Colleges and Universities. These are experiences that make you much more likely to be considered for employment by employers.

Percentages of employers who indicated they would be “much more likely to consider” hiring a college graduate with the following experiences. |

|

| Completion of an internship or apprenticeship | 49% |

| Experience working in a community setting with people from diverse backgrounds or cultures | 47% |

| Had a job or engaged in work-study while in college | 46% |

| Completion of a portfolio or work showcasing skills and integrating college experiences | 45% |

| Exposure to global learning experiences | 44% |

| Completion of multiple courses requiring significant writing assignments | 42% |

| Completion of a community-based or service-learning project | 41% |

| Completion of a research project done collaboratively with faculty | 41% |

| Completion of an advanced comprehensive project in the senior year | 41% |

| According to the Association of American Colleges and Universities’ report, “How College Contributes to Workforce Success: Employer Views on What Matters Most. | |

Check This List. Have You Participated in Any of These High Impact Practices? If Yes, Consider Including Them in Your Portfolio

High-impact practices are those experiences that result in high levels of student learning. As you are brainstorming to think of artifacts to include in your portfolio, look at this list and see if you have experienced any high-impact practices that you might be able to showcase.

- Capstone Courses and Projects

- Collaborative Assignments and Projects

- Common Intellectual Experiences

- Diversity or Global Learning Projects

- First-Year Seminars and Experiences

- Internships or Apprenticeship

- Learning Communities

- Service Learning, Community-Based Learning

- Undergraduate Research

- Writing-Intensive Courses

Closing

Key Takeaways

- Collect, select, reflect, and connect is the key to collecting and relating your artifact.

- Collect a large sample of artifacts.

- Select artifacts that fit the audience, purpose, and story you are telling.

- Reflect on the artifact using the “what, so what, now what method.”

- Connect back to your audience and purpose as well as the key learning items.

- If you have engaged in any high-impact practices, find ways to work them into your portfolio.

Appendix

Do This

As a class, look at these two portfolios and then answer these questions:

Christina Alibozek –Marketing Major

Brenton Warr–Environmental Design

- What types of artifacts did they display?

- Did they write about their artifacts in a meaningful way?

- After reading about their artifacts, what is your impression of the person?

Now, pick three portfolios from the list above in this chapter and answer these questions:

- What types of artifacts did they display?

- Did they write about their artifacts in a meaningful way?

- After reading about their artifacts, what is your impression of the person?

University of Arkansas Students Talk About Their Artifacts

Consider This: Make Your Artifacts Reflect Your Career Competencies

When employers were surveyed and asked what types of things they were looking for to demonstrate that students are career-ready, they told the National Association of Colleges and Employers these things.

- Career and Self-Development

- Communication

- Critical Thinking

- Equity and Inclusion

- Leadership

- Professionalism

- Teamwork

- Technology

TIP: Demonstrate how you have these eight skills, but don’t use the phrase “career competencies” or “career readiness” since those are insider terms for college researchers.

Ideas for Teachers

- Have students write a list of possible artifacts to match each of the course objectives or program goals.

- Assign students a category of artifact and have them find two new examples of how someone showcased that artifact in their portfolio.

- Have students look up three artifacts from the chart and discuss/write/evaluate the efficacy of that artifact’s presentation.

- Give students an artifact and have them brainstorm possible ways to write about that artifact.

- Have students list ten possible artifacts they might include in their portfolio.

- Begin introducing students to the idea of what, so what, and now what by having them look at artifacts from the table and see if they use the pattern.

- Have students write a one-page reflection on a leisure activity and the lessons they learned from the activity.

References

Auburn University Writing. ePorfolio Project.

Cordie, L., Sailors, J., Barlow, B., & Kush, John S. (2019). Constructing a Professional Identity: Connecting College and Career through ePortfolios, International Journal of ePortfolio.

Gallagher, C., & Poklop, L. (2014). ePortfolios and Audience: Teaching a Critical Twenty-First Century Skill. International Journal of ePortfolio, 4(1), 7–20. http://www.theijep.com/pdf/IJEP126.pdf

Khan, S. Identity Development as Curriculum: A Metacognitive Approach in Yancy, K.B. (ed). (2019). ePortfolio as Curriculum: Models and Practices for Developing Students’ ePortfolio Literacy. Stylus Publishing.

Lehman, R. M., Mills, M. D., Gupta, R., & Calderon, O. (2021). Pedagogical intersections: ePortfolio practice and essential learning outcomes for 21st-century success. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2021(166), 59–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20452

National Association of Colleges and Employers. What is Career Readiness? https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined/

National Council on Teaching Quality. Artifact Reflection Guide.

OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com

Parkes, K., Dredger, K., & Hicks, D. (2013). ePortfolio as a Measure of Reflective Practice. International Journal of ePortfolio, 3(2), 99–115. http://www.theijep.com/pdf/IJEP110.pdf

Reynolds, N. & Davis, N. (2014). Portfolio keeping: A guide for students. Bedford St. Martin.

RRC Polytech (2018). ePortfolio – Creating and Uploading Files as Artifacts.

Sanborn, H. B. & Ramirex, J. Chapter 10. Artifacts in ePortfolios: Moving from a Repository of Assessment to Linkages for Learning. Virginia Military Institute

Sowers, K. L., & Meyers, S. (2021). Integrating essential learning outcomes and electronic portfolios: Recommendations for assessment of student growth, course objectives, program outcomes, and accreditation standards. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2021(166), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20451

Stuart, H. (2019). University Writing. | Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike CC License

Stuart, H. (2019) Know your audience ePortfolio. Auburn Writing Center. https://auburn.app.box.com/s/4hylrfb25tp39mixtv49hwkqooz5e2k5

Thibodeaux, T., Harapnuik, D., Cummings, C., & Dolce, J. (2020). Graduate students’ perceptions of factors that contributed to eportfolios persistence beyond the program of study. International Journal of ePortfolio, 10(1), 19–32. https://www.theijep.com/pdf/IJEP353.pdf

Portfolios Cited

Writing

- Lea Bourgade Art Analysis

- Lea Bourgade Scientific Analysis

- Lea Bourgade Blog

- Lea Bourgade Literature Review

- Lea Bourgade Research Proposal

- Katherine Crawford Lesson Plans

- Katherine Crawford Conducting

- Maggie Engler Science -based Research Paper

- Maggie Engler Technical Review

- Maggie Engler Worksheet to Teach a Concept

- Jessica Rae Fillis Conducting

- Hannah Gabrielles Research Paper

- Elise Miller Grant Proposal

- Elies Miller Honors Thesis

- Sara Olmstead-Science Writing

- Hayden Reynoso -Neurobiology Grant

- Carrie White Report

Video

- Emma Allyn Singing Performance Videos

- Lea Bourgade Video of musical performance

- Katherine Crawford Conducting

- Maggie Engler Classroom Projects Where a Video Was Made

- Jacob Blangsner Film

- Jessica Rae Fillis Conducting

- Lynsey Strohminger Video Collage of Teaching

- Lauren Watkins Speech Slide Show

Audio

- Sam Beskind Podcast

- Jessica Fillis Recital

- Jessica Fillis Musical Arrangements

- Sonja Hansen- Podcast

Scientific Reports

Hayden Reynoso–Scientific Poster

Special Projects

Rachel Anders–Study Abroad with an Internship

Serena Hammond-Internship Vet Clinic

Examples.