5 Documenting Your Learning and Personal Growth: Critical Reflection

Lynn Meade

One key aspect of a portfolio is reflective expression. According to Carole Rodgers, “Reflection is a meaning-making process that moves a learner from one experience into the next with a deeper understanding of its relationship with and connections to other experiences and ideas. It is the thread that makes continuity of learning possible.” While the resume and curriculum vitae show what you have done, a reflection shows what you think about what you have done. It allows you to demonstrate thought, and process and document personal growth.

“Reflecting means being intentionally thoughtful about defining an experience, explaining that experience, and determining future implications and actions,” according to Parkes, Dredger, and Hickes. Reflection most often takes the form of writing, but it can also include video or audio reflections. Reflection should take place throughout the portfolio and it “reaches its full potential” when it becomes progressive in that each reflection builds on the others. It is woven into the about me and is an important part of the gallery of artifacts.

Guiding Principles of Reflection

Carole Rogers suggests there are several guiding principles of reflection and at the heart of these are meaning-making, systematic thinking, and personal growth.

- Meaning Making: Reflection is a meaning-making process that moves a learner from one experience into the next with deeper understanding of its relationships with and connections to other experiences and ideas.

- Systematic Thinking: Reflection is a systematic, rigorous, disciplined way of thinking.

- Focused on Personal Growth: Reflection requires attitudes that value personal and intellectual growth.

Now that you know the role of reflection in a portfolio and that it is made up of meaning-making, systematic thinking, and personal growth, let’s look at several ways to get started with writing your reflection.

The Importance of Audience and Purpose

As with all writing, you should have a clear sense of purpose and audience. For example, “I am writing these portfolio reflections to be read by future employers for the purpose of getting a job in the field of marketing” or “I am writing these portfolio reflections to be read by the admittance committee for the purpose of getting accepted into graduate school.” Finally, your purpose may be, “I am writing these reflections as a way to help me better understand my skills so I can visualize a variety of paths in my future.” It is likely that your portfolio will have multiple audiences and you should proceed keeping those audiences in mind. As Gallagher and Poklop suggest, students should consider “inviting different readers to have different experiences of the portfolio by offering them guidance in how to understand, experience, and interact with the portfolio.”

Let’s look at one model of using critical reflection referred to as the what, so what, and now what reflection, also called the Driscoll Cycle. I will explain the cycle, share with you question prompts, offer a video review of the cycle, and then an example of what the cycle looks like when applied.

Critical Reflection

Using the Three Step Model

The Driscoll Cycle of Reflection includes three very basic steps:

- What? Describe what happened.

- So What? Analyze the event.

- Now what? Anticipate future practice based on what you learned.

Let’s break them down one at a time.

What?

In the “what” stage, you should recall what you did and write about it as objectively as possible. Just the facts.

- What happened?

- What is your artifact? Name and describe it.

- What context/background information is important or relevant to your audience?

- What happened in a particular situation? What did you do? What were the results?

- How much did you know about the subject before we started?

- What process did you go through to produce this piece or complete this project/activity?

- What problems did you encounter while you were working on this project/activity? How did you solve them?

- What were the challenges?

- What were powerful learning moments?

Let’s look at an example from a student portfolio. Kaitlyn LaMaster answered the “what” step this way.

Undertaking the task of writing a paper on the “Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Paralysis from Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)” was an enormous challenge that tested my critical thinking and organizational skills. My neurobiology professor had challenged us to select a topic that interested us, dive into the relevant scientific journals, analyze the findings, and produce a final product of professional quality. Despite feeling overwhelmed, I approached the task step by step, reading one journal after the other, and using my available resources to help me prepare. After numerous drafts and revisions, I submitted the paper, and it earned me an A grade, which reinforced my dedication and hard work.

So What?

In the “so what” step, you begin to look for patterns and for what it means. You are talking about moments of significance. Your goal is to write about why this encounter or assignment matters to you.

- What insights did you gain from the project or assignment?

- What are your feelings about this?

- How does what you learned relate to your education or career aspirations?

- What did you learn about yourself from this?

- How does this connect to other skills, experiences, or knowledge?

- What was important about the situation?

- How did you apply course concepts?

- What skills did you use or acquire?

- How did you overcome barriers or challenges?

- What part are you most proud of? Why?

- What would you do differently?

- How was your experience different from what you expected?

- What is the most important thing you learned personally during this project/activity?

- How do you feel about this project/activity?

- What were your goals for this project/activity? Did your goals change as you worked on it? Did you meet your goals?

- What does this project/activity reveal about you as a learner?

- How does this project/activity link to previous experiences/knowledge?

- In what ways did this change how you looked at this subject/topic?

- What did you learn about yourself while working on this?

- What moments are you most proud of your efforts/involvement?

- In what ways have you improved at this kind of work?

- In what ways do you think you need to improve?

Kaitlyn LaMaster answered the “so what” step this way.

This experience taught me invaluable lessons about preparation and organization, which I can apply to any other aspect of life, including sales. I not only researched my topic but also familiarized myself with the best practices for writing a paper of that size. This helped me discover useful resources and applications that aided me in keeping track of the vast amount of information I needed to read, summarize, and cite. With these skills, I could effectively manage dozens of articles, citations, photographs, and other sources, leading to the success of my paper.

Now What?

In the “now what” step, you will write about what you will do next.

- How will this influence the way you approach future projects or endeavors?

- How have you changed or grown because of this experience?

- What will change as a result of this?

- What would you like to learn more about?

- What are you going to do as a result?

- What did this experience teach you?

- How will you apply what you learned from your experience?

- What would you like to learn more about, related to this project or issue?

- What is the impact on others from your project?

- How does this advance the understanding of the topic?

- What is one thing you want people to notice when they look at your work?

Kaitlyn LaMaster answered the “now what” step this way.

Through this experience, I realized the importance of being organized and prepared, and I know this will be an asset in any career, including sales. It has taught me the value of breaking down complex tasks into manageable steps, using available resources, and being organized in managing information, all essential skills in a sales position.

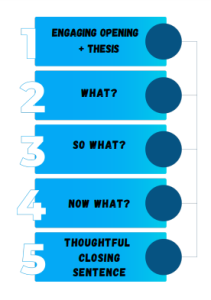

As with all writing, you should have an engaging opening sentence, a clear thesis, and an interesting closing sentence. In essence, each of your reflections should follow this five-step process.

Now that you know the process, let’s take a look at a couple of examples.

Examples of Using the What, So What, Now What for Study Abroad Reflections

Xavier Smith, Career Counselor at the University of Arkansas helps students write about their experiences while studying abroad. Here is his advice and an example.

How can you explain your story in your portfolio? A helpful method in describing your story is a technique called “What? So what? Now what?” “What” calls for you to explain what took place in your involvement or what you noticed. “So what?” calls for you to connect the relevance of it. What was the impact? Discuss any themes, skills, or lessons that were learned. Lastly, describe the “now what”. “Now what” calls for you to describe how you will use the new skills, experience, or insight in future endeavors.

What?

“While studying abroad in Belize, I collaborated with 10 classmates to coordinate rural health clinics in villages in Belize. My classmates and I performed basic diagnostic tests such as the hip-waist test and blood-glucose readings.”

So What?

“Because the village was removed from the city, the locals had limited access to health assessments. I was able to connect with the locals and help work towards better overall community health. The experience allowed me to learn culturally competent communication. It was important that I meet the locals where they were to be able to connect with them. Additionally, I learned how to organize a health clinic and collaborate with local community leaders to be able to build rapport with the community.”

Now What?

“The project informed me of the importance of actively listening to the people I am working with instead of trying to impose my values on them. As a career counselor, I am learning how to listen to the experiences of others and help them discover their unique path. Because of my time in Belize, I am extremely considerate of the perspectives and culture that people bring with them to any space. I intend to continue to grow in understanding through active listening to maximize the efforts of the students.”

Check out Xavier’s Portfolio to see how he uses the “what”, “who what,” “now what” in other examples.

After viewing Xavier’s portfolio, answer these questions:

- Which of the “now what’s” resonated with you?

- How might an employer view his experience studying abroad?

- In what ways did the photos enhance the message?

Can You Identify the What, So What, Now What Parts?

Look at this post from Sydney Maples and see if you can identify the what, so what, and now what parts of this reflection.

The “Empathy” Study: A Virtual Exploration of Homelessness

“While I worked as a programmer in Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab (the campus virtual reality lab), we received a grant to work on an Empathy-based study in virtual reality. I, along with another person within the lab, spent the summer creating a study that immersed participants in a virtual world in which they were homeless on the streets. This in itself required some aspect of science communication, as we both worked on separate components of the study and ultimately tied each component together — which required a lot of justification and debate over best programming practices for the study. I also worked on this study when I was still fairly new to programming, and while most of the knowledge was self-contained within the platform, working on a team to create something so important was part of what got me interested in science communication so early on. It was a wonderful blend of mediums (from video game engines to the Oculus Rift), and watching my programs being used in social psychology studies on participants – including demonstrations at nearby events – was what really made a difference to me and my ability to communicate with others about scientific topics. Not only did I communicate about the current state of homelessness, but I was also given further opportunities to discuss topics pertaining to the environment, such as ocean acidification, before placing participants into a virtual world to see for themselves. Between giving scientific information about the study to participants, to consoling participants if they got upset by what they were experiencing in the virtual world, I learned how to communicate both emotionally and practically as required in a scientific setting.” Sydney Maples

After viewing this example from Sydney, answer these questions:

- Could you identify the “what,” “so what” and “now what?”

- Did she give you enough information about her project that you would understand what it was and why it mattered?

- Compare the format of Xavier to the format of Sydney and talk about the impact of the different approaches.

Looking for more examples to examine. Look at these portfolios and see if you can identify the “what,” “so what” and “now what?”

Laura Barnum, Biochemistry major at University of Waterloo.

Look at the Sample and Analyze

Analyze Hannah Gabrielle’s Course Reflection.

Analyze Carrie Whites Report Reflection

Look at the sample reflections and rate the following items: (did not do) 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9- 10 (excellent)

- The example answered the question, “What?”

- The example answered the question, “So What?” The example represented systematic thinking. (There was evidence of thoughtfulness and connections were made).

- The example represented making meaning. (It didn’t just give an example, it gave meaning to why this example was included or why it mattered).

- The example answered the question, “Now What?” The example demonstrated personal growth.

- The example was engaging.

- The example used college-level professional writing.

- The example had an engaging opening sentence.

- The example had an engaging closing sentence.

- The example had a clear thesis.

Key Take Aways

- Reflection should include meaning-making, systematic thinking, and personal growth.

- Reflections can be written but they can also be audio or videos. They are not limited by modality.

- Portfolio reflections should always be written with the author and purpose in mind.

- The three-step model of writing critical reflection is what, now what, and now what.

- Reflections should have an engaging opening sentence, a thesis statement, and an interesting closing sentence.

Ideas and Resources for Teachers

- Have students use the prompts from “Here are phrases you might use in your reflection” and complete every prompt.

- Ask students to print out their reflections and then in class have them use highlighters to color in what, so what, and now what in different colors.

- Go around the room and ask students to read only the first sentence from their reflection. Have them read only the last sentence. Challenge them to rewrite them to be engaging.

- Have students complete the artifact assignment and the artifact peer review.

- Have students write about a signature assignment.

- Have students do an in-class small-moment reflection about something that happened to them that week.

Additional Resources

Check out this Reflection Toolkit from the University of Edinburgh for ideas and resources.

For an overview of other reflection models, check out the University of Connecticut’s page on Reflection Models and the Global Digital Citizen Foundations Ultimate Cheat Sheet for Critical Thinking.

Consider the suggestions on how to have students reflect from an article on Developing Innovative Reflections from Faculty Development: Lessons Learned:

Reflection Exercises

Looking for some creative reflection prompts? Try out one of these ideas.

Letter to Your Future Self

Write a letter to your current self from your future self.

- What did you learn in college that was instrumental to your growth?

- What goals have you accomplished?

- What thing did you learn in college that you didn’t think was that important at the time but is important to you now?

- What obstacles did you overcome to get where you are?

- What core belief did you cling to?

- What do you want your current self to remember as it moves forward?

Write About Small Moments

The goal of a small moment reflection is to focus on something that was meaningful to you in the moment. For example, in a service learning experience, what is a small thing that you remember that taught you a big lesson? Why was this meaningful to you? When studying abroad, what was a small thing that someone did that made you think? What was a small moment where you realized something important about yourself?

Write Six Words

Choose six independent words that describe an experience. Write your reflection telling why you chose those six words and what that says about the lesson that you learned.

Write About a Signature Assignment

A signature assignment is something that illustrates something that you learned in the course. This signature assignment can be connected to the objectives of the course, the objectives of your program of study, or the objectives of the institution. For Roach and Alvey at the University of Michigan-Flint, it means

A signature assignment is a substantial project within a course that illustrates something quintessential about course content, embeds at least one general education learning outcome, asks students to synthesize and apply learning, gives students agency and choice in the application of their learning, and requires a significant and intentional reflective component to help students identify and articulate relationships between course material, the curriculum, their community, and their sense of self.

One common feature of portfolios is the inclusion of signature assignments. Typically, this involves showing what you did in the class (what), why that mattered (so what), and how you will apply that or how it impacted you in some way (now what).

Serenna Hammons writes about her coursework. In the final part of her reflection, she writes the impact of what she learned:

The most important thing I learned in this course is that I matter. My lazy decisions have a negative impact on the environment, and I have the power to make a positive influence. There are so many things I can do and so many ways to get other people involved. Just my actions alone won’t be monumental, but if everyone made small changes, we can make a big difference. Educating yourself on these things and taking on responsibility is the best way to make a difference.

Tell Your Story Digitally

-

- Tell us the story of how you overcame an obstacle using pictures and videos.

- Create a visual journey of the highlights and insights from your collage journey using pictures and videos.

Write About Your Study Abroad with the Four P’s

Career Specialist Xavier Smith writes about using the 4 P’s of reflection: What are the cool people, places, perks, and projects that you were involved in? By focusing on these areas in your experience, you can provide context to all the cool things you indulged in while abroad. Listing these items is not enough; however, you need to be descriptive of those cool items by utilizing what, so what, and now what. This formula allows you to state what happened, describe its importance to your development, and describe how your new understanding will influence how you navigate the world. Taking this thorough approach in your portfolio will demonstrate your deep thought process and provide viewers with a broader scope or perspective of your experiences and what they mean to you and the larger world.

For a quick review, watch this video published by the McLaughlin Library at the University of Guelph:

Here are phrases you might use in your reflection.

| The most important thing was…

At the time I felt… This was likely due to… After thinking about it… I learned that… I need to know more about… Later I realized… This was because… This was like… I wonder what would happen if… I’m still unsure about… My next steps are… |

The most significant issue arising from this experience was…

Alternatively, this might be due to… I feel this situation arose because… At the time, I felt… Initially, I did not question… At the time, I felt that… This (concept) helps to explain what happened with… This experience highlights the concept of… I developed my understanding of… This experience has highlighted that I need to develop my skills… This provides insight into my own experience of… |

From the Reflective Practice Toolkit, University of Cambridge LibGuide on Reflective Writing and Reflective Prompts by University of Cumbria

References

Bleicher, R. E., & Correia, M. G. (2011). Using a “Small Moments” writing strategy to help undergraduate students reflect on their service-learning experiences. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 15(4), 27-56.

Dewey, J. (1910). How We Think. D.C. Heath and Company.

https://www.schoolofeducators.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/EXPERIENCE-EDUCATION-JOHN-DEWEY.pdf

Eynon, B. & Gambino, L. (2017). High-impact ePortfolio practice. Stylus Publishing.

Gallagher, C., & Poklop, L. (2014). ePortfolios and Audience: Teaching a Critical Twenty-First Century Skill. International Journal of ePortfolio, 4(1), 7–20. http://www.theijep.com/pdf/IJEP126.pdf

Gladd, J. Write What Matters. Open license.

Global Digital Citizen Foundation. Ultimate Cheat Sheet for Critical Thinking.

House, A. T. (2021). Reflection Paper. Student Success, University of Arkansas.

Illinois Center for Innovation in Teaching and Learning. Artifacts and Reflective Self-Expression.

Lengelle, R., Meijers, F., Poell, R., & Post, M. (2014). Career writing: Creative, expressive and reflective approaches to narrative identity formation in students in higher education. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.05.001

Parkes, K., Dredger, K., & Hicks, D. (2013). ePortfolio as a measure of reflective practice. International Journal of ePortfolio, 3(2), 99–115. http://www.theijep.com/pdf/IJEP110.pdf

Reynolds, N. & Davis, N. (2014). Portfolio keeping: A guide for students. Bedford St. Martin.

Reynolds, C. & Patterson, J. (2014). Leveraging the ePortfolio for integrative learning. Stylus Publishing.

Roach, S. & Alvery, J. (2021). Fostering integrative learning and reflection through “signature assignments.” American Association of Colleges and Universities

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., Jasper, M. (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: A user’s guide. Palgrave Macmillan.

Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining Reflection: Another Look at John Dewey and Reflective Thinking. Teachers College Record, 104(4), 842–866.

Ryan, M. (2011). Improving reflective writing in higher education: A social semiotic perspective, Teaching in Higher Education, 16:1, 99-111, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.507311

Spandel, V. (1997). Reflections on Portfolios. Handbook of Academic Learning, Academic Press.

Speller, L. (2019). TIPS for Teaching with Technology: Using ePortfolios to Increase Critical Reflection in the Classroom. https://tips.uark.edu/tips-for-teaching-with-technology-using-eportfolios-to-increase-critical-reflection-in-the-classroom/

University of Cambridge LibGuide. Reflective practice toolkit.

University of Connecticut Center for Teaching and Learning. Reflections and Reflection Models and Sample Reflection Questions

University of Cumbria. Reflective Prompts

University of Edinburg. Reflection Toolkit

Utrel, M. Swinford, R, Fallowfield, S. Angermeier, L (2022). Developing innovative reflections from faculty development: Lessons learned. AAEEBL Portfolio Review.

Walters, S & Jenning, J. ePortfolio Presentation. Teaching and Faculty Support Center

The example of the Driscoll cycle was developed by a student at The Robert Gillespie Science of Learning.