4 Narrative

Over the past century, cinema has evolved into an incredibly complex medium involving the art and science of capturing the moving image, the equally important and co-expressive craft of sound design, not to mention new innovations in virtual reality and immersive technologies that will push the boundaries of what is possible in the years to come.

But one thing hasn’t changed: the importance of a good story.

No matter how innovative the visual delights, how creative the soundscape, or how many millions are spent on the production design and celebrity talent, if it isn’t all in service of a compelling narrative we’ll walk away unmoved and unsatisfied. And good storytelling, of course, has been around at least as long as humans have been able to put together complete sentences. Let’s face it, probably longer.

In this chapter we’ll examine what makes cinematic storytelling unique, how narrative structure shapes our experience of the moving image, how compelling characters move that narrative forward, how the theme and narrative intent inform everything from the mise-en-scène to the cinematography, music, sound design and editing, and how all of this can morph into different narrative forms, or genres, in cinema.

But before we explore the technique of crafting a compelling narrative for cinema, let’s take a look at the essential tool in that process: the screenplay.

THE SCREENPLAY

The screenplay, or script, in cinema is many things at once. Though rarely meant to be read as literature, it is a literary genre unto itself, with its own unique form, conventions, and poetic economy. It is also often a sales pitch, at least in the early stages of production, the best version of the idea, on paper, to attract collaborators and, ultimately, the capital required to make a motion picture. But first and foremost, the screenplay is a technical document, a kind of blueprint for the finished film.

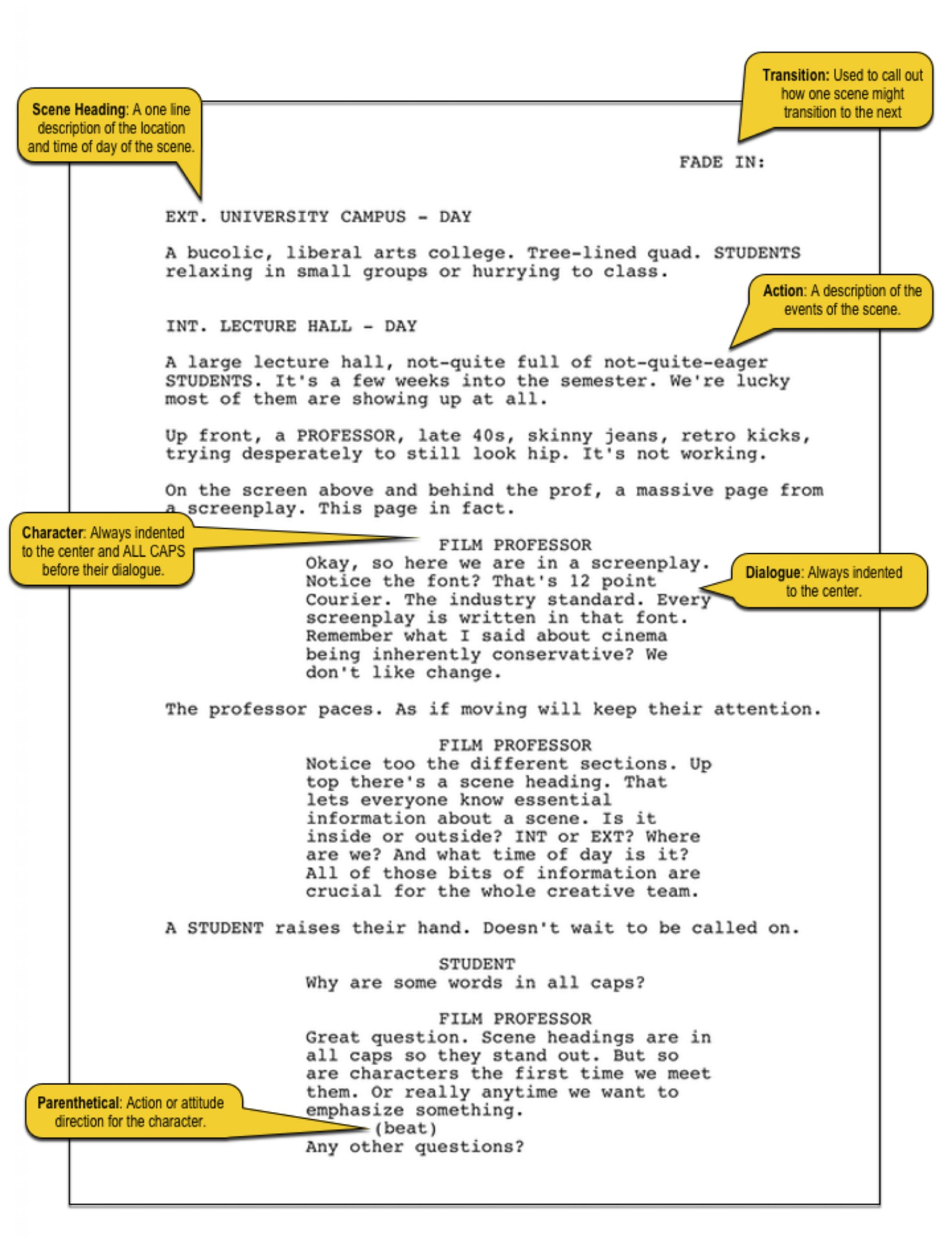

Ever seen a screenplay? Let’s take a look at what one looks like: Every element of the script page is there for a reason and helps everyone on the creative team stay on the same page. Literally. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.) The scene heading, for example, lets everyone know at a quick glance if that particular scene is set inside or outside, INT or EXT, where, exactly, they are supposed to be, and what time of day it is. That information, of course, will affect every member of the crew, from the producers and assistant director responsible for scheduling, to the camera crew responsible for lighting the scene, to the production designer responsible for the look of the location, to the transportation crew responsible for getting everyone there safely.

Every element of the script page is there for a reason and helps everyone on the creative team stay on the same page. Literally. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.) The scene heading, for example, lets everyone know at a quick glance if that particular scene is set inside or outside, INT or EXT, where, exactly, they are supposed to be, and what time of day it is. That information, of course, will affect every member of the crew, from the producers and assistant director responsible for scheduling, to the camera crew responsible for lighting the scene, to the production designer responsible for the look of the location, to the transportation crew responsible for getting everyone there safely.

But notice too how economical the writing must be. There is no room to probe the inner life of characters or spin off into detailed descriptions of the space. And that is one of the most important aspects of great screenwriting: the economy of language. Imagine you’re watching a film or tv show and your roommate is in the other room making a nice medium rare New York strip and a mushroom risotto (ok, fine, a bowl of ramen). They don’t want to miss anything, so you have to describe in detail everything you’re seeing and hearing by yelling across the apartment. What do you include? What do you leave out? Obviously you want to include what characters are saying, but beyond that, probably just the essentials. In fact, as a general rule of thumb, every page of script should equal about a minute of screen time. That doesn’t always work out exactly, but does tend to average out over the length of the screenplay. So there simply isn’t time to include anything but the essentials and allow the other creative collaborators on the team the freedom to interpret the rest.

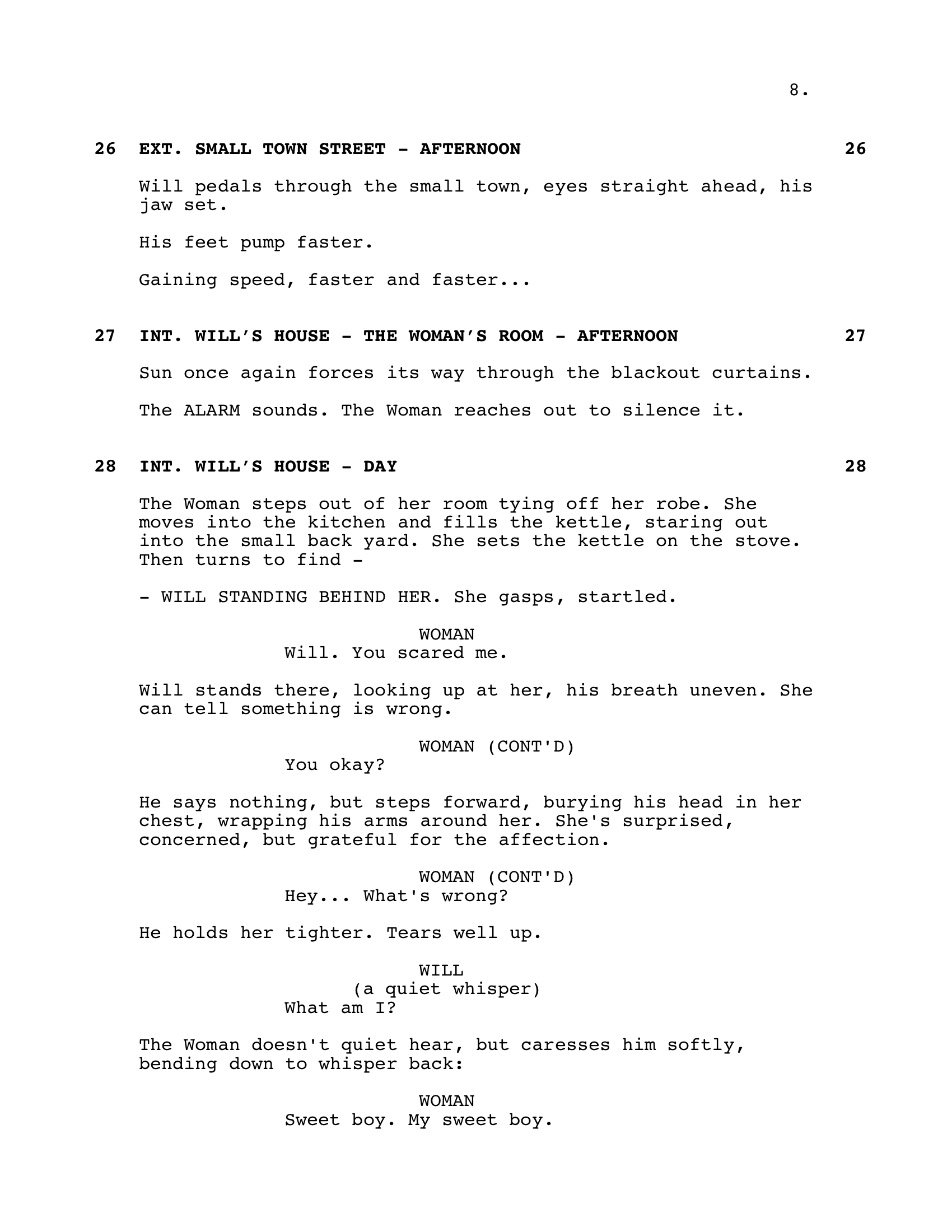

Let’s take a look at another page from a screenplay and how that compares to what we see on the screen in the finished film: Now here’s the scene as it was shot and edited from that screenplay:

Now here’s the scene as it was shot and edited from that screenplay:

First, notice the clip is about one minute, equal to that one page of screenplay. Second, how does the script page compare to the finished scene? What do you notice in the script that isn’t on the screen? And what do you notice about the finished film that isn’t in the script? You’ll likely notice that there is no mention in the screenplay about how the camera moves or how it frames the image. Nor do you notice anything about the music, or the boy’s wardrobe, or that dog in the background, or the fact that it’s raining. But you might notice mention of an alarm clock that doesn’t show up on screen.

There are any number of reasons for some of the differences. Some of them are intentional. How the camera moves is the cinematographer’s job, not the screenwriter’s. Likewise, the boy’s wardrobe is the concern of the production designer and wardrobe department (though the script does mention the woman’s robe because that is important to the narrative, and that is the screenwriter’s job). But some of the differences are due to the realities of production. Just like a blueprint is a plan for a building, the screenplay is a plan for a motion picture. Once you start building it, you have to confront and overcome hundreds, maybe thousands of variables you could not anticipate. Maybe the weather turns on the last day of filming and you’ve got to incorporate a thunderstorm into the story. Or a neighbor is out walking their dog and ends up in a shot, so you have to layer in a dog barking in the sound design and carry that over to the next scene. Or maybe once you’re in post-production and the editor is putting it all together, they realize that last line would work much better over the next scene. And that alarm clock? Maybe the director decided that was too cliché once they were on the set and wanted to try something different with their actor. (All of the above are true. I should know, I wrote, directed and edited the film in question. Fortunately, all three of us got along reasonably well).

The most important thing to remember is that cinema is a collaborative medium. There’s always a give and take between the script and the finished film, just like there is between the director and the screenwriter, cinematographer, production designer, sound designer, actors, editor, etc., etc. And as much as a screenplay can and should be a great read, it is, ultimately, a technical document, a plan for something exponentially more complex.

And now that we have a sense of what this technical document looks like, let’s examine more generally how a screenplay works. That is, how it tells a uniquely cinematic story.

NARRATIVE STRUCTURE

Here’s the recipe for a good story:

1 protagonist.

1 goal.

A whole bunch of obstacles.

That’s it. Pretty much every story ever told can be boiled down to those three elements: A protagonist pursuing a goal confronted by obstacles. Cinematic storytelling draws from this same narrative source, and in that sense, is not so different from a good novel or even just a good yarn spun around the campfire. In fact, a lot of what we’ll discuss here can apply to those other literary genres. Compelling characters are important no matter the form the story takes. Likewise, a clear theme or narrative intent from the storyteller. And sure, cinema, just like novels or short stories or even poetry, come in all shapes and sizes, otherwise known as genres, from thrillers to westerns, comedies to romance.

But I’d like to make the (somewhat controversial) case that cinema has developed its own unique structure, a rhythm to how a story is told cinematically. Not so much a “rule” to which all screenwriters must conform, more a pattern or set of patterns that writers have found most effective in communicating cinematically. This pattern has developed over time, evolved along with all of the other elements of cinematic language, and is, in fact, continuing to evolve as cinema moves into new, more open-ended forms like limited and streaming series. For now, let’s examine just one cinematic form, the narrative feature film.

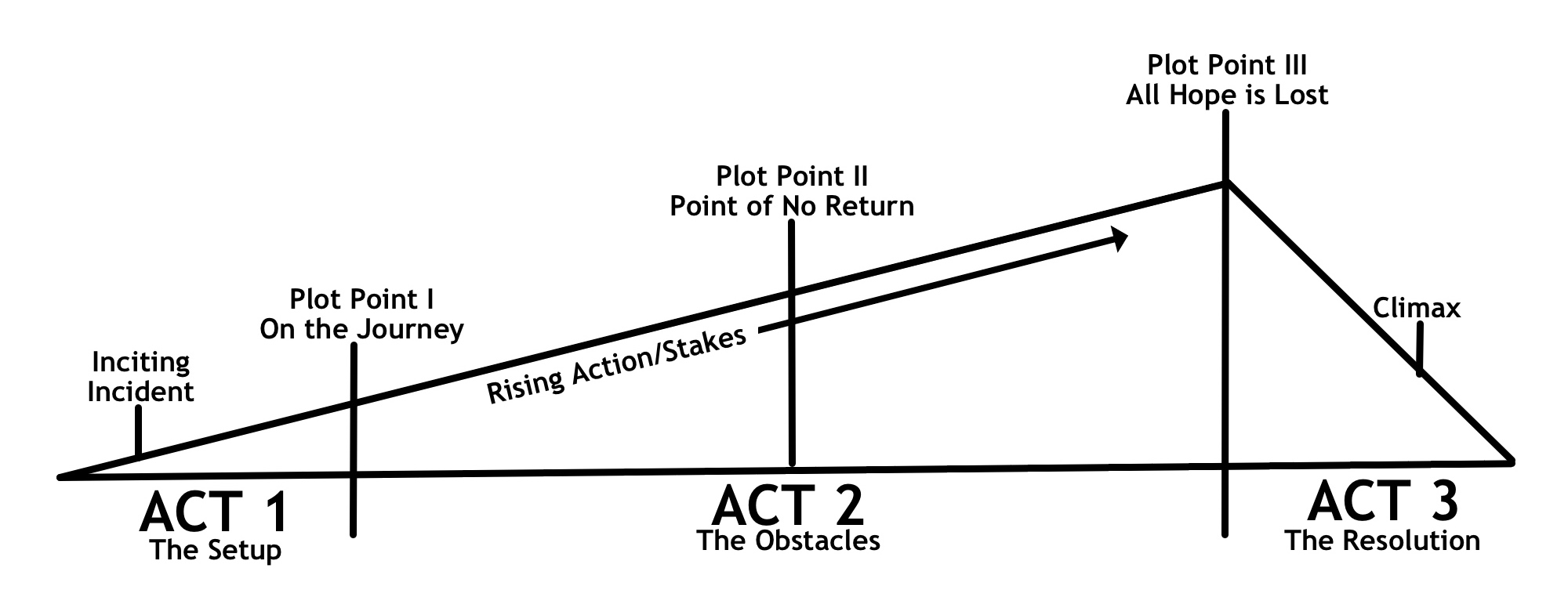

The closed-ended, narrative feature film, what we typically call a “movie” with a beginning, middle and an end and a running time anywhere from 90 minutes to over 2 hours, has been around for more than a century and served as a kind of foundational form in cinematic storytelling (though its cultural dominance has arguably lessened over the past decade or so, but we’ll get to that). Over that time, and in Hollywood in particular, it has been refined and perfected into what we can describe as a three-act structure:

Act one, which generally runs to 25 or 30 pages (or the first 25 to 30 minutes of screen time), introduces the protagonist, sets up their world, and clarifies the goal they’ll be pursuing for the rest of the story. It might also introduce a central antagonist, or it might wait until later. But typically, by page 25 or 30, we know who we’re rooting for, what they want, and what’s in their way. Maybe they’ve resisted going on the journey to that point, but by the end of act one, they are launched into act two, sometimes against their will.

Act one, which generally runs to 25 or 30 pages (or the first 25 to 30 minutes of screen time), introduces the protagonist, sets up their world, and clarifies the goal they’ll be pursuing for the rest of the story. It might also introduce a central antagonist, or it might wait until later. But typically, by page 25 or 30, we know who we’re rooting for, what they want, and what’s in their way. Maybe they’ve resisted going on the journey to that point, but by the end of act one, they are launched into act two, sometimes against their will.

Act two, which is usually about twice as long as act one, is all about the obstacles. Our protagonist must confront and overcome each one, and typically, the stakes get higher every time. That is, with every obstacle, the protagonist must risk more and more, making their journey more and more difficult. Often, those obstacles are put there by someone or something specific, the antagonist. But the obstacles could also be internal, some part of the protagonist’s own psychology. Either way, there’s usually a midpoint, right around page/minute 55 or 60, where the protagonist has a choice: they can turn back, give up on the pursuit of the goal, or double-down and never look back. Of course, they double-down. But by the end of act two, around page/minute 85 or 90, our protagonist meets their biggest obstacle yet. In fact, it seems to seal their fate. All hope is lost. They, and we, feel they will never reach their goal after all.

But that’s not what we paid good money to see.

Act three, which is usually about the same length as act one, is all about our protagonist rallying to overcome that last obstacle leading to a climactic showdown and a resolution to their story. Usually that means they reach the goal defined in act one. But sometimes the journey clarifies a new goal, or they realize they always had what they were searching for and just needed to see it in themselves (insert eye roll here). But you get the idea, act three brings some kind of resolution.

This narrative structure as outlined above may seem all too familiar, and for some, its predictability is everything that’s wrong with mainstream, Hollywood cinema. But I would argue that the cinematic three-act structure is one of the most important contributions to the global story-telling form in the past century. The Greeks had their tragedies, Shakespeare his five-act epics, Japanese poets the haiku. Hollywood has given us the three-act movie. And like the haiku, it is the structure of the three acts that, perhaps ironically, provides movies their creative freedom. We know the stories will resolve, the protagonist will reach their goal, that’s why we show up at the theater, but it’s the how – how this particular filmmaker is going to solve this particular problem – that keeps us in the seats. For all the rigidity of the haiku form (and come to think of it, that form of three lines of varying length echoes cinematic three act structure pretty nicely), no two poems are the same. Hopefully we can say the same of great cinema.

To be clear, the three-act structure is not an explicit industry standard or a rule to which screenwriters must conform. In fact, it is less a writing technique than it is an analytic tool, a way of breaking down cinematic stories for analysis. Unlike stage plays, there are no explicit act breaks in the script itself. And some writers actively work against that structure in an effort to push beyond expectations in cinema. The films of Quentin Tarantino, for example, often “break the rules” for how cinema is supposed to work (and as a result his scripts often read more like novels than screenplays). But even Tarantino accepts the importance of setting up audience expectations and, eventually, paying them off. Even he understands that the journey of a protagonist toward their goal is littered with obstacles and follows an arc toward resolution. And more often than not, the exceptions ultimately prove the “rule” of how effective the three-act structure has become. Not just because screenwriters find it useful, but because we, as the audience, have internalized it as part of our shared cinematic language:

But as cinema has evolved into other forms, including television and streaming series, so too has narrative structure evolved. Beginning nearly half a century ago with the rise of broadcast television, cinematic storytelling for the small screen required an adjustment to the pace and rhythm of how a protagonist pursued their goal. Commercial interruptions, for example, came at regular intervals, forcing writers into a four- or even five-act structure with cliffhangers at each break to make sure the audience didn’t change the channel. Even today, broadcast television scripts still have explicit act breaks in the text to indicate where a commercial break might appear.

As binge-worthy streaming series have become the dominant form of cinematic entertainment, we see yet another evolution. With no commercial breaks, writers need not write a cliffhanger every 10 or 15 minutes. But they are keenly aware of how important it is that viewers hit play on the next episode. So, the narrative structure of a streaming series tends to apply the classic three-act structure to an entire eight- or ten-episode season, converting that eight- to ten-hour experience into one that echoes the ups and downs of a two-hour feature film. And, interestingly, that evolution of the form has in turn informed the narrative structure of the most popular feature film franchises. What are The Fast and the Furious or Transformers film franchises but multi-billion dollar series with each episode doled out every two or three years?

Which is why these innovations in the form represent an evolution of cinematic language, not a radical break. Just as cinematic storytelling itself is simply an evolution of the classic, age-old formula: A protagonist pursuing a goal confronted by obstacles.

COMPELLING CHARACTERS AND THE PRIMARY NARRATOR

Now, let’s talk about that protagonist for a moment. Narrative structure may be a critical component of cinematic language, but ultimately, structure is another word for plot, and we don’t go to the movies to root for plots, we root for people. If there isn’t a compelling character or characters at the center story, all of the plot points (and special effects) in the world won’t hold our attention or capture our imagination.

But what does it mean to be a compelling character? Some distinguish between round and flat characters. A round character is a complex, often conflicted character with a deep internal life who usually undergoes some kind of change over the course of the story. A flat character lacks that complexity, does not change at all over the course of the story, and is usually there only to help the more round characters on their journeys.

Obviously, most protagonists are, or should be, round characters. Though sometimes protagonists can be rather flat (check out any Steven Seagal flick from the 90s… or better yet, don’t), and sometimes side characters who are only peripheral to the main story can be incredibly complex and undergo dramatic transformation. Still, a protagonist should at the very least be interesting, and that does not necessarily mean they are inherently good. In fact, often the most interesting protagonists are flawed in some fundamental way, and part of the fun is watching them struggle with that flaw. That’s one reason Superman is such a difficult character to pull off on screen. He’s just so… good. And he doesn’t change all that much. But Batman? That guy is dark. And that’s what makes him so much fun to watch (and perhaps why he’s so much more successful at the box office).

Sometimes those flaws can be so deep and so disturbing that the character is no longer a protagonist and is more an anti-hero. An anti-hero is an unsympathetic hero pursuing an immoral goal, and somehow we end up rooting for them anyway. Think of basically every heist movie. Or every vigilante action movie. Or any Tarantino movie for that matter. The main characters are all essentially criminals intent on breaking the law. And we can’t wait to see how they pull it off:

To be clear, an anti-hero is not the same as an antagonist. The antagonist’s role is to stop the hero from reaching their goal. In The Dark Knight (2008), Batman is the protagonist, the hero, and the Joker is the antagonist. But in Joker (2019), the Joker is the protagonist, in this case an anti-hero, and the police, ostensibly the “good guys”, are the antagonists.

Whether protagonist or anti-hero, the central character of a cinematic narrative should always drive the story forward. We are on their journey, and it’s their actions that move us through the plot.

But… they are not in control. That is to say, they are not, in fact, the primary narrator in cinema.

Let me explain.

When you read a novel, unless it is written in the first person, it’s not any one character in the book telling you the story. One could argue it’s the author herself, but the singular “voice” of the narrator is more an abstraction than a person.

The next time you are watching a film or series, take a step back and ask yourself: Who or what is telling this story? Not what character are we following or with whom do we most closely identify in the story, but who or what is actually relaying the events. Yes, there’s the screenwriter and the director and ultimately the editor who are all responsible for narrative as we receive it. Just like the author of a novel. But moment to moment, the primary narrator in cinema is always the camera.

Let’s face it, we’re all voyeurs. We like sitting in the dark and peering into other people’s lives unnoticed and undetected. That’s what cinema is. And our window into those lives is the camera frame. The camera dictates where we look and when. The camera provides all the information we need to construct the narrative unspooling at 24 frames per second.

But more generally, we can distinguish between two kinds of narration, two ways the camera tells the story. Does the camera restrict our view to the experiences of just one character? Or does it allow us to follow all sorts of characters, round and flat, major and minor, protagonist and antagonist, wherever they might go? Restricted narration refers to stories that never leave the protagonist, restricting our access to any other character unless they are in the same space as our hero. Omniscient narration can follow any character, even minor ones, if it helps tell the story. But in both cases, it’s the camera than controls the story. It’s the camera that serves as the primary narrator.

THEME AND NARRATIVE INTENT

A clear narrative structure and compelling, round characters are crucial elements in our shared cinematic language. And once we understand these principles of how a screenplay works, how it goes about telling a story, we can look more deeply into what, exactly, it is trying to say. We’ll spend more time on that towards the end of this book, but for now, it’s important to distinguish between a plot – what happens in a film – and a theme – what the film is really about. Star Wars (1977) is about a farm boy saving a princess and defeating a planet-destroying weapon wielded by the evil Empire. That’s the plot. But it’s really about believing in oneself and the difference one brave person can make in the face of overwhelming evil. That is its narrative intent. It’s that underlying idea that activates the plot, defines the characters, and leads us to a satisfying resolution.

That does not mean every film or series has a “message” like those saccharine after-school specials. But it does mean that great cinema is organized around an idea, an arguable point, that can focus the action and clarify character. A clear and well-planned narrative theme can serve as a unifying principle, informing every other element of the cinematic experience. Not just plot and character, but mise-en-scène, cinematography, sound design and editing as well. In Star Wars, the climactic Death Star sequence is a spectacular action set piece, but it also serves the central narrative theme. Luke Skywalker becomes the last pilot, one tiny fighter against a planet-sized weapon. And to defeat it, he must draw upon skills he learned back on the farm.

Compare that to the action set piece at the center of G.I. Joe: Rise of Cobra (2009). A missile filled with nanomites strikes the Eiffel Tower and destroys it in a blaze of CGI glory. What’s a nanomite? Doesn’t matter. The sequence is not connected to a clear theme because there is no clear theme, just a plot, a sequence of events where things happen. One is left with the impression that the only reason the Eiffel Tower scene exists is because someone thought it would look cool on screen. And it does. I guess. But it doesn’t move us. It’s meaningless, a mere plot point. And that’s often why cinematic spectacles can leave us flat. They look cool, but have no unifying theme, no narrative intent aside from the spectacle itself.

But when that spectacle is tied to a clear theme, one that we can identify with and even argue over, then cinema can become transformative.

Take Pixar’s Toy Story (1995) for example. The plot is fairly simple. A child’s favorite toy is threatened by the arrival of a shiny new toy. His jealousy leads to them both becoming lost and working together to return home. A simple sequence of events. And with the innovation of 3D animation at the time, that might have been all it needed to hold our attention if not capture our imagination. But the movie is much more than that. It’s really about friendship and the importance of self-sacrifice. And every scene serves that theme, serving either as counterpoint or confirmation. The plot, then, is not simply a random sequence of events, it is a carefully planned dramatization of the theme where every obstacle encountered reveals something important about the hero’s journey. That’s what makes Toy Story a classic, and not just another cartoon.

GENRE IN CINEMA

Genre is likely a term you’ve encountered before. We use it when analyzing literature to distinguish between different types of stories. The word itself is French (I know, the French again), and it literally means “a kind” or type. And yes, it’s related to the word gender, as in a “type” of person. And even the word generic, as in, non-specific, plain or even uninteresting.

And that’s the blessing and the curse of genre. It’s a useful way to categorize types of cinematic narrative – westerns, romantic comedies, horror, superhero – but it also implies a non-specificity, a certain sameness to films of a type.

But sometimes… that’s exactly what we want.

When we go to see a romantic comedy, we know we’re going to see two people meet early on in the story and then spend about 90 minutes overcoming all sorts of obstacles to be together. There will likely be some terrible misunderstanding or other calamity late in the film that dooms their relationship (end of act two!), and then someone will run through an airport or stand outside in the rain to profess their true feelings and they’ll finally be together. We know all of this before the opening credits. That’s the point. We want to see how this particular filmmaker gets them there. But they better get there. That’s why we paid for our ticket.

These similarities, and they extend to types of characters, settings, themes, even musical scores, are called narrative conventions. Cinematic genres, just like literary genres, are grouped according to these conventions. We know a Western when we see one because they share similar settings (the 19th century American west), characters (the lone gunslinger, the homesteading widow, the disillusioned sheriff) and themes (rugged individualism and frontier justice). The same with Science Fiction, Horror, Gangster movies, and the Musical.

Genre distinctions are handy for us as viewers when deciding what kinds of stories we want to engage, but they are even more handy for producers and studios when it comes to meeting the demand of audiences. Cinema is an incredibly capital intensive medium, and the more targeted the content, the more likely filmmakers will see a return on that investment. In that sense, genre is a convenient shorthand for both the people who consume cinema and the people who produce it:

And as we discussed with the three-act structure, the apparent rigidity of narrative conventions when it comes to genre might seem like a recipe for boredom. A formula instead of an art form. But structure doesn’t dictate predictability. It can just as easily inspire creativity. Just like that “predictable” romantic comedy, genre can pose a creative challenge to surprise an audience that already thinks it knows what’s coming.

Of course, sometimes a filmmaker can lean into one genre, setting up expectations, and then really pull the rug out from under us:

But perhaps more importantly, genre – again, like three-act structure – is really more an analytic technique than a writing tool. While some screenwriters work firmly and unequivocally within a particular genre, the narrative conventions we associate with certain types of films help us analyze how a particular filmmaker approaches the fundamental questions in any story: Who is the hero? What do they want? How are they going to get it?

1 protagonist.

1 goal.

A whole bunch of obstacles.

Video Attributions:

How Three-Act Screenplays Work (and why it matters) by Lindsay Ellis. Standard YouTube License.

Top 10 Movie Anti-Heroes by WatchMojo.com. Standard YouTube License.

Introduction to Genre Movies – Film Genres and Hollywood by Ministry Of Cinema. Standard YouTube License.

10 Movies That Made Shocking Genre Shifts Halfway Through by WhatCulture. Standard YouTube License.