6 Editing

They say a film is made three times. The first is by the screenwriter. The second by the director and crew. And the third is by the editor in post-production.

I don’t know who “they” are, but I think they’re onto something.

When the screenwriter hands the script off to the director, it is no longer a literary document, it’s a blueprint for a much larger, more complex creation. The production process is essentially an act of translation, taking all of those words on the page and turning them into shots, scenes and sequences. And at the end of that process, the director hands off a mountain of film and/or data, hours of images, to the editor for them to sift through, select, arrange and assemble into a coherent story. That too is, essentially, an act of translation.

The amount of film or data can vary. During the Golden Age of Hollywood last century, most feature films shot about 10 times more film than they needed, otherwise known as a shooting ratio of 10:1. That includes all of the re-takes, spoiled shots, multiple angles on the same scene, subtle variations in performance for each shot, and even whole scenes that will never end up in the finished film. And the editors had to look at all of it, sorting through 10 hours of footage[1] for every hour of film in the final cut.

They didn’t know it then, but they were lucky.

With the rise of digital cinema, that ratio has exploded. Today, it is relatively common for a film to have 50 or 100 times more footage than will appear in the final cut. The filmmakers behind Deadpool (2016), for example, shot 555 hours of raw footage for a final film of just 108 minutes. That’s a shooting ratio of 308:1. It would take 40 hours a week for 14 weeks just to watch all of the raw footage, much less select and arrange it all into an edited film![2]

So, one of the primary roles of the editor is to simply manage this tidal wave of moving images in post-production. But they do much more than that. And their work is rarely limited to just post-production. Many editors are involved in pre-production, helping to plan the shots with the end product in mind, and many more are on set during production to ensure the director and crew are getting all of the footage they need to knit the story together visually.

But, of course, it’s in the edit room, after all the cameras have stopped rolling, that editors begin their true work. And yes, that work involves selecting what shots to use and how to use them, but more importantly, editing is where the grammar and syntax of cinematic language really come together. Just as linguistic meaning is built up from a set sequence of words, phrases and sentences, cinematic meaning is built up from a sequence of shots and scenes. A word (or a shot) in isolation may have a certain semantic content, but it is the juxtaposition of that word (or shot) in a sentence (or scene) that gives it its full power to communicate. As such, editing is fundamental to how cinema communicates with an audience. And just as it is with any other language, much of its power comes from the fact that we rarely notice how it works, the mechanism is second nature, intuitive, invisible.

But before we get to the nuts of bolts of how editors put together cinema, let’s look at how the art of editing has evolved over the past century. To do that, we have to go back to the beginning. And we have to go to Russia.

SOVIET MONTAGE AND THE KULESHOV EFFECT

As you may recall, the earliest motion pictures were often single-take actualités, unedited views of a man sneezing, workers leaving a factory or a train pulling into a station. It took a few years before filmmakers understood the storytelling power of the medium, before they realized there was such a thing as cinematic language. Filmmakers like Georges Melies seemed to catch on quickly, not only using mise-en-scène and in-camera special effects, but also employing the edit, the joining together of discrete shots in a sequence to tell a story. But it was the Russians, in this early period, that focused specifically on editing as the essence of cinema. And one Russian in particular, Lev Kuleshov.

Lev Kuleshov was an art school dropout living in Moscow when he directed his first film in 1917. He was only 18 years old. By the time he was 20, he had helped found one of the first film schools in the world in Moscow. And he was keenly interested in film theory, more specifically, film editing and how it worked on an audience. He had a hunch that the power of cinema was not found in any one shot, but in the juxtaposition of shots. So, he performed an experiment. He cut together a short film and showed it to audiences in 1918. Here’s the film:

After viewing the film, the audience raved about the actor and his performance (he was a very famous actor at the time in Russia). They praised the subtly with which he expressed his aching hunger upon viewing the soup, and the mournful sadness upon seeing the child in a coffin, and the longing desire upon seeing the scantily clad woman. The only problem? It was the exact same shot of the actor every time! The audience was projecting their own emotion and meaning onto the actor’s expression because of the juxtaposition of the other images. This phenomenon – how we derive more meaning from the juxtaposition of two shots than from any single shot in isolation – became known as The Kuleshov Effect.

Other Russian filmmakers took up this fascination with how editing works on an audience, both emotionally and psychologically, and developed an approach to filmmaking known as the Soviet Montage Movement. Montage is simply the French term for “assembly” or “editing” (even the Russians had to borrow words from the French!), but Russian filmmakers of the 1920s were pushing the boundaries of what was possible, testing the limits of the Kuleshov Effect. And in the process, they were accelerating the evolution of cinematic language, bringing a sophisticated complexity to how cinema communicates meaning.

The most famous of these early proponents of the Soviet Montage Movement was Sergei Eisenstein. Once a student of Kuleshov’s (though actually a year older), Eisenstein would become one of the most prolific members of the movement. Perhaps his most well-known film, Battleship Potemkin (1925), contains a sequence that has become one of the most famous examples of Soviet montage, and frankly, one of the most famous sequences in cinema period. It’s known as The Odessa Steps Sequence. You may remember it from Chapter One. Let’s take another look:

One thing you might notice about that sequence: It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, at least in terms of a logical narrative. But Eisenstein was more interested in creating an emotional effect. And he does it by juxtaposing images of violence with images of innocence, repeating images and shots, lingering on some images, and flashing on others. He wants you to feel the terror of those peasants being massacred by the troops, even if you don’t completely understand the geography or linear sequence of events. That’s the power of the montage as Eisenstein used it: A collage of moving images designed to create an emotional effect rather than a logical narrative sequence.

EDITING SPACE AND TIME

In the hundred or so years since Kuleshov and Eisenstein, we’ve learned a lot about how editing works, both as filmmakers and as audience members. In fact, we know it so well we hardly have to give it much thought. We’ve fully accepted the idea that cinema uses editing to not only manipulate our emotions through techniques like the Kuleshov Effect, but also to manipulate space and time itself. When a film or tv episode cuts from one location to another, we rarely wonder whether the characters on screen teleported or otherwise broke the laws of physics (unless of course it’s a film about wizards). We intuitively understand that edits allow the camera – and by implication the viewer – to jump across space and across time to keep the story moving at a steady clip.

The most obvious example of this is the ellipsis, an edit that slices out time or events we don’t need to see to follow the story. Imagine a scene where a car pulls up in front of a house, then cuts to a woman at the door ringing the doorbell. We don’t need to spend the screen time watching her shut off the car, climb out, shut and lock the door, and walk all the way up to the house. The cut is an ellipsis, and none of us will wonder if she somehow teleported from her car to the front door (unless, again, she’s a wizard). And if you think about it for a moment, you’ll realize ellipses are crucial to telling a story cinematically. If we had to show every moment in every character’s experience, films would take years or even decades to make much less watch!

Other ways cinema manipulates time include sequences like flashbacks and flashforwards. Filmmakers use these when they want to show events from a character’s past, or foreshadow what’s coming in the future. They’re also a great indicator of how far cinematic language has evolved over time. Back in the Golden Age of Hollywood, when editors were first experimenting with techniques like flashbacks, they needed ways to signal to the audience, “Hey, we’re about to go back in time!” They would employ music – usually harp music (I’m not sure why, but it was a thing) – and visual cues like blurred focus or warped images to indicate a flashback. As audiences became more fluent in this new addition to cinematic language, they didn’t need the visual cues anymore. Today, movies often move backwards and forwards in time, trusting the audience to “read” the scene in its proper context without any prompts. Think of films like Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) which plays with time throughout, re-arranging the sequence of events in the plot for dramatic effect and forcing the viewer to keep up. Or a more recent film like Greta Gerwig’s adaptation of Little Women (2019) which also moves backwards and forwards in time, hinting at the shift through mise-en-scène and subtle changes in performance.

Another, much more subtle way editing manipulates time is in the overall rhythm of the cinematic experience. And no, I don’t mean the music. Though that can help. I mean the pace of the finished film, how the edits speed up or slow down to serve the story, producing a kind of rhythm to the edit.

Take the work of Kelly Reichardt for example. As both director and editor on almost all of her films, she creates a specific rhythm that echoes the time and space of her characters:

Sometimes an editor lets each shot play out, giving plenty of space between the cuts, creating a slow, even rhythm to a scene. Or they might cut from image to image quickly, letting each flash across the screen for mere moments, creating a fast-paced, edge-of-your seat rhythm. In either case, the editor has to consider how long do we need to see each shot. In fact, there’s a scientific term for how long it takes us to register visual information: the content curve. A relatively simple shot of a child’s smile might have a very short content curve. A more complex shot with multiple planes of view and maybe even text to read would have a much longer content curve. Editing is all about balancing the content curve with the needs of the story and intent of the director for the overall rhythm of each scene and the finished film as a whole.

This is why editing is much more than simply assembling the shots. It is an art that requires an intuitive sense of how a scene, sequence and finished film should move, how it should feel. In fact, most editors describe their process as both technical and intuitive, requiring thinking and feeling:

CONTINUITY EDITING

Maybe it’s obvious, but if editing is where the grammar and syntax of cinematic language come together, then the whole point is to make whatever we see on screen make as much sense as possible. Just like a writer wants to draw the reader into the story, not remind them they’re reading a book, an editor’s job, first and foremost, is to draw the viewer into the cinematic experience, not remind them they’re watching a movie. (Unless that’s exactly what the filmmaker wants to do, but more on that later.) The last thing most editors want to do is draw attention to the editing itself. We call this approach to editing continuity editing, or more to the point, invisible editing.

The goal of continuity editing is to create a continuous flow of images and sound, a linear, logical progression, shot to shot and scene to scene, constantly orienting the viewer in space and time and carrying them through the narrative. All without ever making any of that obvious or obtrusive. It involves a number of different techniques, from cutting-on-action to match cuts and transitions, and from maintaining screen direction to the master shot and coverage technique and the 180 degree rule. Let’s take a look at these and other tricks editors use to hide their handiwork.

Cutting on Action

The first problem an editor faces is how and when to cut from one shot to the next without disorienting the viewer or breaking continuity, that is, the continuous flow of the narrative. Back in Chapter Two, I discussed one of the most common techniques is to “hide” the cut in the middle of some on-screen action. Called, appropriately enough, cutting-on-action, the trick is to end one shot in the middle of an action – a character sitting down in a chair or climbing into a car – and start the next in the middle of the same action. Our eyes are drawn to the action on screen and not the cut itself. The edit disappears as we track the movement of the character. Here’s a quick example:

The two shots are radically different in terms of the geography of the scene – one outside of the truck, the other inside – but by cutting on the action of the character entering the truck, it feels like one continuous moment. Of course we notice the cut, but it does not distract from the scene or call attention to itself.

And now that you know what to look for, you’ll see this technique used in just about every film or tv show, over and over, all the time.

Match Cuts

Cutting-on-action is arguably the most common continuity editing trick, but there are plenty of other cuts that use the technique of matching some visual element between two contiguous shots, also known as a match cut. There are eyeline match cuts that cut from a shot of a character looking off camera to a shot of whatever it is they are looking at, graphic match cuts that cut between two images that look similar (the barrel of a gun to James Bond in an underground tunnel, for example), and even subject match cuts that cut between two similar ideas or concepts (a flame from a matchstick to the sun rising over the desert in David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962)).

Almost all of these examples rely on a hard cut from one shot to the next, but sometimes an editor simply can’t hide the edit with some matching action, image or idea. Instead, they have to transition the viewer from one shot to the next, or one scene to the next, in the most organic, unobtrusive way possible. We call these, well, transitions. As discussed in Chapter Two, you can think of these as conjunctions in grammar, words meant to connect ideas seamlessly. The more obvious examples, like fade-ins and fade-outs or long dissolves, are drawn from our own experience. A slow fade-out, where the screen drifts into blackness, reflects our experience of falling asleep, drifting out of consciousness. And dissolves, where one shot blends into the next, reflect how one moment bleeds into and overlaps with another in our memory. But some transitions, like wipes and iris outs, are peculiar to motion pictures and have no relation to how we normally see the world. Sure, they might “call attention to themselves,” but somehow they still do the trick, moving the viewer from one shot or scene to the next without distracting from the story itself.

Wondering what some of these match cuts and transitions look like? Check out several examples of each (along with some not-so-invisible edits like jump cuts) here:

Screen Direction

Maintaining consistent screen direction is another technique editors use to keep us focused on the story and keep their work invisible. Take a look at this scene from Casablanca:

We are entering the main setting for the film, a crowded, somewhat chaotic tavern in Morocco. Notice how the camera moves consistently from right to left, and that the blocking of the actors (that is, how they move in the frame) is also predominantly from right to left, until we settle on the piano player, Sam. The flow of images introduces the tavern as if the viewer were entering as a patron for the first time. This consistent screen direction helps establish the geography of the scene, orienting the viewer to the physical space. An editor concerned about continuity never wants the audience to ask “Where are we?” or “What’s going on?” And obviously, this isn’t something an editor can do after the fact all by themselves. It requires a plan from the beginning, with the director, the cinematographer, the production designer and the editor all working together to ensure they have the moving images they need to execute the scene.

Some filmmakers can take this commitment to consistent screen direction to the extreme to serve the narrative and emphasize a theme. Check out this analysis of Bong Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer (2013):

Master Shot and Coverage

Consistent screen direction is an important part of how continuity editing ensures the audience is always aware of where everyone is located in relation to the setting and each other. Another common technique to achieve the same goal is to approach each scene with a master shot and coverage.

The idea is fairly simple. On set during production, the filmmaker films a scene from one, wide master shot that includes all of the actors and action in one frame from start to finish. Then, they film coverage, that is, they “cover” that same scene from multiple angles, isolating characters, moving in closer, and almost always filming the entire scene again from start to finish with each new set-up. When they’re done, they have filmed the entire scene many, many times from many different perspectives.

And that’s where the editor comes in.

It’s the editor’s job to build the scene from that raw material, usually starting with the master shot to establish the geography of the scene, then cutting to the coverage as the scene plays out, using the best takes and angles to express the thematic intent. They can stay on each character for their lines of dialogue, or cut to another character for a reaction. They can also cut back to the master shot whenever they choose to re-establish the geography or re-set the tone of the scene. But maybe most importantly, by having so many options, the editor can cut around poor performances or condense the scene by dropping lines of dialogue between edits. Done well, the viewer is drawn into the interaction of the characters, never stopping to ask where they are or who is talking to whom, and hopefully never even noticing a cut.

Let’s take a look at a scene from Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash (2014), shot and edited in the classic master shot and coverage technique:

The scene opens with a master shot. We see both characters, Andrew and Nicole, in the same frame, sitting at a table in a café. The next shot is from the coverage, over Nicole’s shoulder, on Andrew as he reacts to her first line of dialogue. Then on Nicole, over Andrew’s shoulder as she reacts to his line. The editor, Tom Cross, moves back and forth between these two shots until Andrew asks a question tied to the film’s main theme, “What do you do?” Then he switches to close-up coverage of the two characters. Tension builds, until there is a subtle clash between them, a moment of conflict. And what does the editor do? He cuts back to the master shot, resetting the scene emotionally and reorienting the viewer to the space. The two characters begin to reconnect, and the editor returns to the coverage, again shifting to close-ups until the two find a point of connection (symbolized by an insert shot of their shoes gently touching). The rhythm of this scene is built from the raw materials, the master shot and the coverage, that the editor has to work with. But more than just presenting the scene as written, the editor has the power to emphasize the storytelling by when to cut and what shots to use.

The master shot and coverage technique gives the editor an incredible amount of freedom to shape a scene, but there is one thing they can’t do. A rule they must follow. And I don’t mean one of those artistic rules that are meant to be broken. Break this rule, and it will break the continuity of any scene. It’s called the 180 degree rule and it’s related to the master shot and coverage technique.

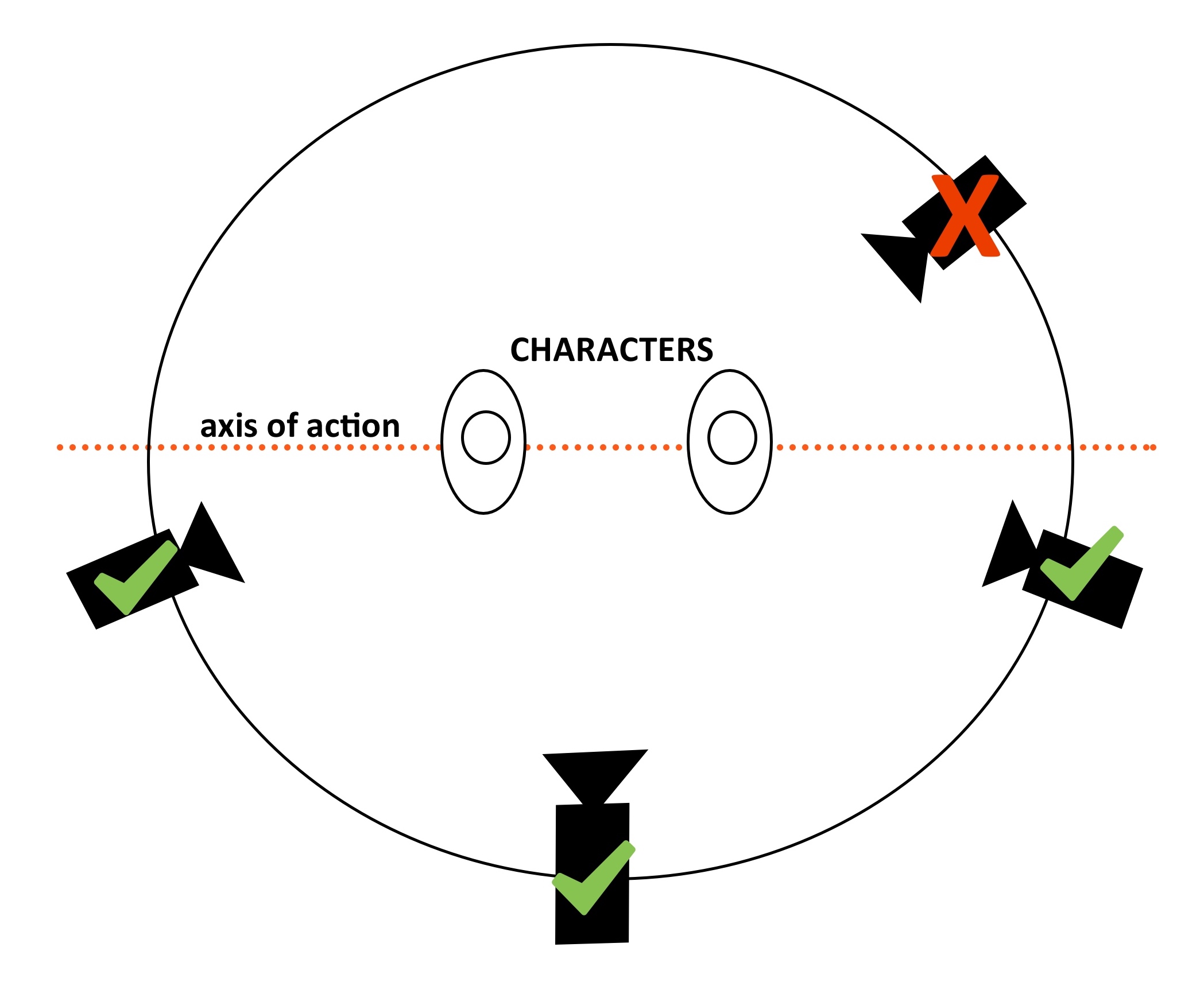

Basically, the 180 degree rule defines an axis of action, an imaginary line that runs through the characters in a scene, that the camera cannot cross: Once the master shot establishes which side of the action the camera will capture, the coverage must stay on that side throughout the scene. The camera can rotate 180 degrees around its subject, but if it crosses that imaginary line and inches past 180 degrees, the subjects in the frame will reverse positions and will no longer be looking at each other from shot to shot. Take a look at that scene from Whiplash again. Notice how the master shot establishes the camera on Andrew’s left and Nicole’s right. Every subsequent angle of coverage stays on that side of the table, Andrew always looking right to left, and Nicole always looking left to right. If the camera were to jump the line, Andrew would appear to be looking in the opposite direction, confusing the viewer and breaking continuity.

Once the master shot establishes which side of the action the camera will capture, the coverage must stay on that side throughout the scene. The camera can rotate 180 degrees around its subject, but if it crosses that imaginary line and inches past 180 degrees, the subjects in the frame will reverse positions and will no longer be looking at each other from shot to shot. Take a look at that scene from Whiplash again. Notice how the master shot establishes the camera on Andrew’s left and Nicole’s right. Every subsequent angle of coverage stays on that side of the table, Andrew always looking right to left, and Nicole always looking left to right. If the camera were to jump the line, Andrew would appear to be looking in the opposite direction, confusing the viewer and breaking continuity.

Now, I know I just wrote that this is not one of those artistic rules that was meant to be broken. But the fact is, editors can break the rule if they actually want to disorient the viewer, to put them into the psychology of a character or scene. Or if they need to jump the line to keep the narrative going, they can use a new master shot to reorient the axis of action.

Parallel Editing

All of these techniques, cutting-on-action, match cuts, transitions, consistent screen direction and the master shot and coverage technique are all ways that editors can keep their craft invisible and maintain continuity. But what does an editor do when there is more than one narrative playing out at the same time? How do you show both and maintain continuity? One solution is to use cross-cutting, cutting back and forth between two or more narratives, also known as parallel editing.

Parallel editing has actually been around for quite some time. Perhaps one of the most famous early examples is from D. W. Griffith’s Way Down East (1920). Kuleshov had already demonstrated the power of juxtaposing shots to create an emotional effect. But Griffith, among others, showed that you could also create a sense of thrilling anxiety by juxtaposing two or more lines of action, cross-cutting from one to another in a rhythmic pattern. In a climactic scene from the film, a man races to save a woman adrift on a frozen river and heading straight for a dangerous waterfall. To establish these lines of action and to increase our own sense of dread and anxiety, the editor cuts from the man to the woman to the waterfall in a regular, rhythmic pattern, cross-cutting between them to constantly remind the audience of the impending doom as we cheer on our hero until the lines of action finally converge. Here’s the scene:

By cross-cutting in a regular pattern – man, woman, man, waterfall, woman, man, woman, waterfall – the audience is not only drawn into the action, they are also no longer paying attention to the editing itself, thus maintaining continuity.

This technique has become so common, so integral to our shared cinematic language, that editors can use our fluency against us, subverting expectations by playing with the form. Check out this (rather disturbing) clip from Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991):

The scene uses the same parallel editing technique as Way Down East, using cross-cutting to increase our anxiety as two lines of action converge. But in this case, the editor subverts our expectations by revealing there were actually three lines of action, not two. But the trick only works if parallel action is already part of our cinematic language.

DISCONTINUITY EDITING

Continuity, or “invisible” editing is all about hiding the techniques of filmmaking, allowing an audience to be carried away by the cinematic experience and never reminding them they are watching a motion picture. But what if that’s exactly what you want to do? What if you want to break the usual continuity of cinema? Maybe you want to dramatize the fractured mind of a character. Or maybe you want to comment on the act of watching a film itself. There may be any number of reasons an editor might break the rules outlined above. And the really talented ones know how to do it on purpose and to great effect.

In some ways, this brings us back full circle to Soviet montage editing. Eisenstein was more interested in creating an emotional effect than creating a linear narrative. Take another look at his edit of the Odessa steps sequence above. In it, he knits together a series of discontinuous shots that do very little to establish geography or the spatial relationships of characters in the scene. In fact, we may be constantly asking the questions “Where are we?” and “What’s going on?” But for Eisenstein, that was precisely the point. He wants you to feel disoriented.

One of the most common discontinuity tricks is the jump cut, a cut between two shots of the same subject with little or no variation in framing. Here’s a quick example:

In this case, the jump cut is used for comedic effect to show the passage of time. But it can also be used to dramatize a chaotic or disoriented situation or state of mind. For example, check out this clip from Jean Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960), especially the last 30 seconds or so:

As the main character is cornered by the police, Godard uses jump cuts and reverse screen direction to deliberately confuse and disorient the viewer, putting them in the character’s state of mind. Godard, part of the French New Wave of filmmakers in the 1960s and 70s, would become known for his consistent use of discontinuity editing in his films.

A more modern example of discontinuity editing, and my personal favorite, is Steven Soderbergh’s The Limey (1999). The film follows a British ex-con as he visits Los Angeles in search of his daughter’s killer. A pretty straight-forward thriller. But Soderbergh is not terribly interested in a straight-forward thriller. Instead, he tells the story through the main character’s fractured memory. And his editor, Sarah Flack, uses discontinuity editing to dramatize that narrative idea. But don’t take my word for it. Check out this video essay that covers just about everything I love about Flack’s editing in Soderbergh’s film:

Ultimately, Flack’s editing choices in The Limey, despite the disorientation and discontinuity, serve the thematic intent of the film. And that’s the editor’s job. To piece together the shots, scenes and sequences into a coherent – if not always continuous – order, a syntax built from our shared cinematic language.

Video Attributions:

Soviet Film – The Kuleshov Effect (original) by Lev Kuleshov 1918 by MediaFilmProfessor. Standard YouTube License.

Battleship Potempkin – Odessa Steps scene (Einsenstein 1925) by Thibault Cabanas. Standard YouTube License.

Kelly Reichardt: “Elaborated Time” by Lux. Standard YouTube License.

How Does an Editor Think and Feel? by Every Frame a Painting. Standard YouTube License.

Cuts & Transitions 101 by RocketJump Film School. Standard YouTube License.

Casablanca First Cafe Scene by Leahstanz25. Standard YouTube License.

Snowpiercer – Left or Right by Every Frame a Painting. Standard YouTube License.

Whiplash – Date scene by Jack ss. Standard YouTube License.

Way Down East (1920) D. W. Griffith, dir. – Final Chase Scene by FilmStudies. Standard YouTube License.

Example of Parallel Editing in “The Silence of the Lambs” (1991) by Gabriel Moura. Standard YouTube License.

Neighbors Clip – Discontinuity by Russell Sharman. Standard YouTube License.

Breathless drive+shooting by Angela Ndalianis. Standard YouTube License.

The Limey: Crash Course Film Criticism #10 by CrashCourse. Standard YouTube License.

- Footage is a common way to refer to the recorded moving image, whether it’s on celluloid film or digital media. The term comes from the fact that physical film was measured in feet, with a standard reel of 35mm film measuring 1000 feet (or about 11 minutes at 24 frames per second). The technology has changed, but the terminology has stuck. ↵

- https://vashivisuals.com/shooting-ratios-of-feature-films/ ↵