10 Privacy

We’ll return to the sport of football for our opening hypothetical. The scenario introduces ethical concerns with reporting about suicide, and details of a hypothetical suicide are included in the presentation below.

Study the following presentation slides by using the forward button or clicking on sections of the control bar.

In this opening hypothetical, a key ethical concern surfaces: To what extent do family and friends deserve privacy in their time of grief?

In the previous lesson, we studied how ethical media professionals try to minimize harm by protecting the privacy of vulnerable sources.

In this lesson, we’ll cover privacy in more detail. As we’ve already seen in several case studies, two SPJ principles frequently conflict: minimizing harm and reporting truth.

MINIMIZING HARM vs. REPORTING TRUTH

MINIMIZING HARM vs. REPORTING TRUTH

Ray McCaffrey is the director for the Center of Ethics in Journalism at the University of Arkansas. In the following audio, he discussed some tension between reporting truth and minimizing harm.

McCaffrey emphasized that, in some instances, public performance by public officials can supersede privacy. In general, public figures (including celebrities) enjoy less right to privacy than common citizens.

PRIVACY FOR PROTESTERS?

Protests in the summer of 2020 sparked an ongoing journalistic debate about privacy of those who protest in public. Most journalists would argue that it harms the future of our democracy if we don’t have accurate portrayals of historic events. Part of that accuracy is capturing images of people who are publicly protesting. This argument maintains that if you want to maintain privacy, you shouldn’t protest in public.

Because of advancements in facial recognition technology and an increase in disinformation on social media, though, media professionals should at least consider unintended consequences from publishing images of protesters. Those images can wind up being used in ways that the photographer never intended.

Read the following and consider the extent to which protesters give up expectations of privacy:

• Photographers are being called on to stop showing protesters’ faces. Should they? – Poynter

The article includes the following advice from SPJ’s ethics chair:

Reporters who cover ongoing protests should take the time to understand the demographics of the group involved — like whether they are mostly underage individuals or if they’re in one of the communities being impacted by the issue.

For collegiate editors on campuses where protests are held, a related ethical question is whether reporters should include the names of protesters in their coverage.

IDENTIFYING PROTESTERS

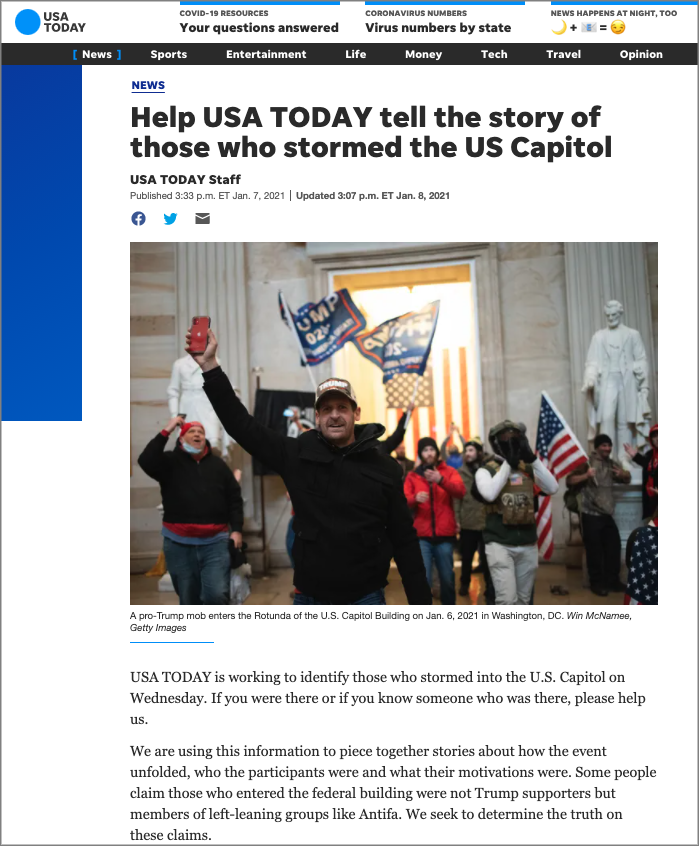

In an unusual case example from 2021, USA Today asked readers to help “tell the story of those who stormed the U.S. Capitol” by identifying protesters/rioters in published photos. See a screenshot of the story below:

Critics suggested that by inviting readers to identify protesters, USA Today failed to minimize harm, especially for protesters who did nothing illegal. Instead, USA Today assumed a role that is better left to law enforcement officials.

COMPASSION, CRIME STORIES AND MUGSHOTS

News media outlets have a history of covering crime stories, sometimes including mugshots.

Today, however, many journalists are rethinking routine coverage of crime stories and the use of mugshots, mostly to protect privacy and minimize harm. For example, if a college freshman is arrested for a minor offense and the student newspaper publishes a story about the incident along with a mugshot, that story link may appear at the top of web search results for a decade or more. In worst-case scenarios, this can hamper job opportunities and harm a person’s reputation for a lifetime.

This ethical debate gained increased attention as a result of privacy laws that the European Union began enforcing in 2018. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) includes provisions that allow individuals to have past personal data erased, which is sometimes called a right to be forgotten.

The following headline and article from Slate framed the issues involved in crime coverage and the use of mugshots:

• Who deserves to have their past mistakes “forgotten”? – Slate

One British professor used as a source in the Slate article argued that “the way technology reminds us of our past harms our ability to forgive and make decisions in the present.”

The Online News Association has a helpful web page that offers guidance for a variety of scenarios involving removal requests:

• Removing material from your archives – ONA

PROTECTION FROM POLITICS

In the mid-2020s, political implications surfaced that forced editors to consider takedown requests from sources who had previously shared their opinions about politically sensitive topics or participated in public protests. In some cases, journalists themselves asked for their bylines to be removed from previously published work.

Poynter reported on people who, fearing retribution from the Trump administration, asked editors to remove their names from old news stories. Requests came from government workers, teachers and green card holders who worried that they might face legal repercussions or employment risks because of opinions and information attributed to them in archived news content.

Collegiate student media editors received takedown requests as well, including from international student journalists on U.S. campuses who had previously published opinion columns or investigative stories.

In 2025, a group of national student media organizations issued a student media alert that encouraged student media leaders to review their takedown/anonymity policies and “consider easing some of the normal restrictions you may have applied to takedown requests.”

The alert said that “granting retraction or anonymity requests could protect those most vulnerable from being punished for their speech.”

In one highly publicized instance, Rümeysa Öztürk, a Turkish student attending Tufts University in Massachusetts, was detained and threatened with deportation. According to reporting from the Associated Press, her lawyers said the threat was an apparent retaliation for an opinion article she co-wrote for the campus newspaper.

VICTIMS OF SEXUAL ASSAULT AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

In the United States, news journalists agree that they will rarely identify victims of sexual assault by name. This is usually not a legal mandate; it is an ethical practice intended to minimize harm and maintain privacy for victims. To report accurately, journalists also must be careful in their use of legal terms, which can vary by state, related to sexual assault, sexual abuse, rape, sexual harassment, sexual misconduct and domestic violence.

Here’s guidance contained in the Associated Press Stylebook:

We generally do not identify, in text or images, those who say they have been sexually assaulted or subjected to extreme abuse. We may identify victims of sexual assault or extreme abuse when victims publicly identify themselves.

Even if an adult victim has consented to be identified, this can be a difficult decision, especially if the victim is not a public figure. For example, a victim who wants to be identified may want to decrease the stigma attached to rape; on the other hand, identification may not be in the victim’s long-term best interest.

Another consideration is that people who are accused in cases involving sexual assault or abuse are frequently identified by name, as part of police records, in news reports. However, the person making the accusation is usually not identified. This can lead to concerns that only one side of the story is being told.

Here’s an overview of some key privacy issues in cases of sexual assault and domestic violence:

• Is it ever okay to name victims? – Columbia Journalism Review

DATA COLLECTION

Can comedy sometimes serve journalistic educational purposes? Maybe so. Instead of reading a lengthy text explanation for this section of the chapter, you can watch John Oliver explain how data brokers operate and what they’re doing with our private information: (Warning: The video contains some profanity)

Data Brokers: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO)

In the video above, Oliver cited one media example about how the U.S. military buys location data from ordinary apps, meaning data from the apps that everyday consumers use can eventually wind up being used for military tracking.

• How the U.S. military buys location data from ordinary apps – Vice

The article from Vice included this:

A Muslim prayer app with over 98 million downloads is one of the apps connected to a wide-ranging supply chain that sends ordinary people’s personal data to brokers, contractors, and the military.

Increasingly, the field of advertising relies on data to isolate and target consumer demographics. Thus, data collection and advertising have become entwined. In short, professionals in advertising and public relations have an ethical obligation to prioritize users’ privacy when they collect data and use personal information to target individual consumers. Easier said than done.

COLDPLAYGATE

Beyond online data privacy, the Coldplaygate incident in 2025 became a stark reminder that cameras are almost everywhere. During a Coldplay concert, a kiss-cam briefly showed a company CEO embracing a female co-worker who was not his wife. The two were startled and immediately sought to avoid being shown on camera.

Beyond online data privacy, the Coldplaygate incident in 2025 became a stark reminder that cameras are almost everywhere. During a Coldplay concert, a kiss-cam briefly showed a company CEO embracing a female co-worker who was not his wife. The two were startled and immediately sought to avoid being shown on camera.

A follow-up New York Times feature story included this advice from Charles Lindsey, an associate professor of marketing at University at Buffalo School of Management.

“If you’re in a public place, there is absolutely no expectation of privacy. When you’re in a public place, whether it be a public park, a store, a concert, there are cameras, and if it’s on camera, you can’t take it back.”

Some PR professionals used company accounts to join the trend of posting humorous memes, while others did not want to post a funny response to an awkward incident that may have caused embarrassment for private people not included on camera (such as the CEO’s wife). The now-former CEO’s company, Astronomer, responded through subtle humor in a video ad featuring Gwyneth Paltrow, the ex-wife of Coldplay singer Chris Martin.

Consider whether, if you had been a PR executive, you would have approved a humorous social-media meme based on Coldplaygate.

SUICIDE

In the chapter opening, you considered a hypothetical scenario about a suicide. In that case, concerns about privacy extend to family and friends who may not want the cause of death to be widely reported.

The AP Stylebook provides the following guidance:

Generally, AP does not cover suicides or suicide attempts, unless the person involved is a well-known figure or the circumstances are particularly unusual or publicly disruptive.

For most instances, AP discourages reporters from detailing the method of suicide. Also, the use of “committed suicide” implies a criminal act, so AP suggests, when necessary, to simply say that a person died by suicide.

Also, journalists should avoid the adjective “successful” to describe an act of suicide.

Another helpful resource, the Suicide Reporting Toolkit, listed five reasons why journalists should report suicide responsibly:

1. Irresponsible suicide reporting can impact the number of suicides.

2. To avoid contributing to further deaths by glamorizing suicide through vivid language or by inciting vulnerable people to kill themselves through excessive description of the method.

3. To avoid focusing on negative perceptions, stereotypes, sensationalism and deviance.

4. Responsible reporting can mitigate the number of deaths by suicide.

5. Responsible reporting can help dispel myths about suicide death and can educate the public on available treatments to help those in need.

Note that the third item pertains specifically to privacy, which is our topic for this chapter. The online toolkit also offers specific advice for journalists who cover suicides:

• The Suicide Reporting Toolkit

Ethical consideration of suicide coverage can be an intersection between psychology and journalism. The Psychology Today staff offers a warning about suicide contagion, when vulnerable audience members may more strongly consider suicide as a result of media coverage. Research suggests that “portraying suicide in responsible, straightforward ways—and emphasizing that help is always available—can help minimize the risk and better educate the public about suicide.”

- Media Coverage and Suicide Contagion – Psychology Today

CLOSING REVIEW

WRITE ABOUT IT

Answer each question in approximately three to five sentences. Use support from chapter content in your responses.

1. Based on the chapter content about suicide reporting, especially the Suicide Reporting Toolkit, in what circumstances do you think it is appropriate and/or beneficial to report on a suicide? To what extent would you, as a student journalist, report the hypothetical suicide described in the chapter opening?

2. Based on content and links in this chapter, when, if ever, is it ethically appropriate for news organizations to update or remove crime stories containing specific identification? Also, what is a useful threshold for publishing new content about people charged with crimes?

3. Do protesters automatically give up expectations of privacy while they are protesting?

4. Was it ethically appropriate for USA Today to seek help in identifying people who may be criminal suspects?

5. Discuss your key takeaways from the chapter section titled “Data Collection.” What did you learn that surprised you the most?

6. As a PR executive, you would have approved a humorous social-media meme based on Coldplaygate? What would be the primary factors in your decision-making process?

7. Under what circumstances is it appropriate or acceptable to name a victim of a sex crime?