8 Plagiarism and Fabrication

As an opening for our lesson on plagiarism and fabrication, let’s look at a couple of cartoons.

Study the following presentation slides by using the forward button or clicking on sections of the control bar.

In his book The Ethical Journalist, Gene Foreman provides useful definitions for plagiarism and fabrication.

• Fabrication can be defined as “making things up and passing them off as genuine.”

• Plagiarism involves “taking credit for phrases, sentences, paragraphs, or even an entire story” even though someone else created it.

FABRICATION PURE AND SIMPLE

Jayson Blair was the key figure in one of the nation’s most famous fabrication and plagiarism cases. Blair invented numerous stories for the New York Times.

The following three videos will give you historical perspective:

1. A Fragile Trust: Jayson Blair, plagiarism and the New York Times

2. Jayson Blair: “Slippery-Slope” To Fabricating Stories | Where Are They Now | Oprah Winfrey Network

3. Jayson Blair On Resigning from the New York Times | Where Are They Now | Oprah Winfrey Network

Blair resigned from the New York Times in 2003. Since then, journalists have increasingly relied upon websites, online search engines and social media platforms as fact-checking tools, but that hasn’t squashed all instances of plagiarism and fabrication.

For example, in 2022 editors from USA Today removed stories written by Gabriela Miranda. An audit of Miranda’s work revealed that “some individuals quoted were not affiliated with the organizations claimed and appeared to be fabricated,” while “some stories included quotes that should have been credited to others.”

• USA TODAY removed 23 stories from website, other platforms following audit of reporter’s work – USA Today

As shown in the screenshot below, when readers clicked on a link for an affected story on the USA Today website, they saw only an editor’s note stating that the story had been removed.

PLAGIARISM AND POLITICS

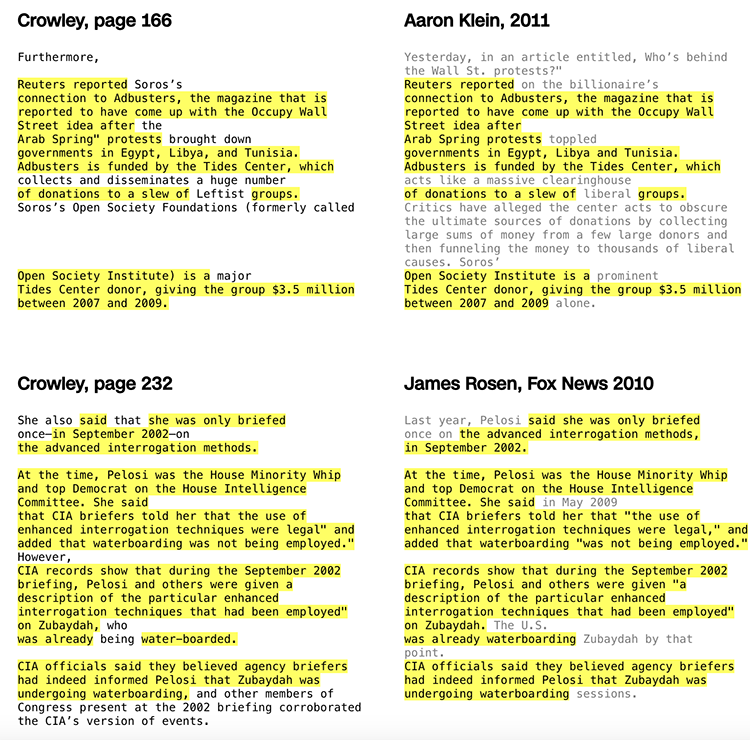

Our case example from this section occurred in 2016 when President Donald Trump initially named conservative author and TV personality Monica Crowley to be senior director of strategic communications for the National Security Council. Shortly thereafter, however, CNN Money reported that Crowley had plagiarized large portions of her book What the (Bleep) Just Happened, published in 2012.

The Trump administration at first stood by Crowley and her best-selling book but later reversed course. The CNN Money story listed approximately 60 instances of alleged plagiarism. It included each quote from Crowley’s book side by side with the original source. This side-by-side comparison – which is rarely done within an article – made this incident convenient for our examination. Crowley contended the criticism of her work was “a political hit job.”

Below is a screenshot from a portion of CNN Money’ s side-by-side comparison.

You can read the full CNN Money story and study the complete side-by-side comparison here:

• Trump national security pick Monica Crowley plagiarized multiple sources in 2012 book – CNN Money

Although Crowley’s publisher suspended sales of her book, she labeled the CNN Money story as a political hit job. Read more about her reaction from Salon:

FABRICATION AND POLITICS

News editors should never assume that the content of a story is true without consulting multiple sources to verify key information. That seems simple and obvious, but occasionally the lure of a juicy political story triumphs over ethical fact-checking. As a result, fabricated stories are published.

A 2021 story in the New York Post reported that, as part of a welcome kit, migrant children had been given copies of a children’s book written by Vice President Kamala Harris. The story was fabricated, but that didn’t stop the false narrative from spreading on social media. Read the New York Times’ summary of the incident:

• New York Post Reporter Who Wrote False Kamala Harris Story Resigns – NY Times

(University of Arkansas students have free access to the NY Times by signing up via campus email credentials)

Similarly, false stories and commentaries circulated in 2021, saying that the Biden administration wanted to dramatically limit the consumption of red meat in the United States to as little as one hamburger per month per person. A PBS video explained how the fabrication spread and clarified a misleading connection to a university research project. You can view the video and read a transcript here:

• Conservatives beef with Biden over false red meat claims – PBS

Misinformation comes from both ends of the political spectrum. Leading up to the 2024 presidential election, a New York Times article reported that “left-wing misinformation is having a moment.” The social media deception included posts claiming, without evidence, that Trump may have staged an assassination attempt.

PLAGIARISM AND PUBLIC RELATIONS

PR professionals regularly send out news releases hoping that they will be published in news media outlets. But if a company’s PR news release is published word-for-word on a local news website, what should the byline say? Read the following analysis from the Plagiarism Today website:

• The Problem with Press Release Plagiarism – Plagiarism Today

The analysis included this observation about situations in which news organizations do not divulge that a published story originated from a press release:

… if a person offers up their work to be plagiarized, plagiarism appears to be a victimless crime. However, the plagiarized party is not the only victim. Plagiarism, at its most fundamental level, is a lie. It’s a person saying that they wrote or created something that they did not. That lie, however, isn’t told to the plagiarized party, but to the audience.

FABRICATION AND SPORTS

In an episode of the Pardon My Take podcast from Barstool Sports, Fox sports reporter Charissa Thompson said that earlier in her career she had fabricated quotes from coaches in her sideline reports.

“I would make up the reports sometimes, because the coach wouldn’t come out at halftime, or it was too late and I didn’t want to screw up the report.”

Thompson faced immediate backlash from other professional sports journalists. On the social media platform X (formerly Twitter), ESPN sideline reporter Molly McGrath posted the following:

“Young reporters: This is not normal or ethical. Coaches and players trust us with sensitive information, and if they know that you’re dishonest and don’t take your role seriously, you’ve lost all trust and credibility.”

And Kevin Smith, a board member of the Society of Professional Journalists, was even more critical in a response to The Washington Post.

“This is just appallingly bad journalism to engage in, and to brag about it and defend it as harmless is beyond the pale. The SPJ’s ethics code addresses truth, harm, independence and accountability. She gets the trifecta for destroying three ethical tenets with her lying.”

One could argue that Thompson did not report truthfully, harmed her profession, and did not take accountability for her actions.

FABRICATION IN AI-GENERATED CONTENT

In the field of philosophy, the term bullshit isn’t necessarily a questionable word choice. It’s also an academic term initially put forth by Princeton professor Harry Frankfurt in his influential book On Bullshit.

Three researchers at the University of Glasgow in Scotland took Frankfurt’s work a step further to argue that large language models such as ChatGPT can be considered bullshit machines. Their research essay was titled “ChatGPT Is Bullshit.”

In the audio below, one of the co-authors, James Humphries, explained the difference between soft bullshit and hard bullshit based on the potential motives of large language models and, by extension, those who design and use them for gain in professional media environments.

As a follow-up, co-author Michael Townsen Hicks provided advice to media professionals about using metaphors to describe large language models.

THE ALLURE OF ‘FAKE NEWS’

Fabricated stories have surfaced throughout the history of U.S. journalism, no matter if the false information spreads via a printed newspaper article or a TikTok video.

People who claim that a story is “fake news” are suggesting that content has been fabricated. But research shows that our minds retain fabricated content because it is novel or outlandish, and because it arouses emotional impact. Read this research summary from Harvard’s Nieman Lab.

• The neuroscience of how fake news grabs our attention, produces false memories, and appeals to our emotions – Harvard’s Nieman Lab

A key takeaway from the article focused on emotional appeal:

The ability of fake news to grab our attention and then highjack our learning and memory circuitry goes a long way to explaining its success. But its strongest selling point is its ability to appeal to our emotions.

For those who want to read more about news literacy and the psychological appeal of misinformation, here’s an additional resource:

• The psychology of misinformation: Why we’re vulnerable – First Draft

IMAGE MANIPULATION AS FABRICATION

It’s not just text that can be fabricated. In some instances, photo or video manipulation can be a form of fabrication. If you skim through examples at the following link, you’ll see examples of photo manipulation that came more than a century before the advent of Photoshop and digital tools for image editing.

• Photo tampering throughout history (Georgia Tech College of Computing)

As an extreme example, software today can create realistic-looking faces that represent fake people.

• Designed to deceive: Do these people look real to you? – NY Times

(University of Arkansas students have free access to the NY Times by signing up via campus email credentials)

Finally, the video below from Wired magazine shows how sources can be matched to targets in creating (or even fabricating) a deepfake video.

Everybody Dance Now – Wired

Writing for the Society of Professional Journalists, Rod Hicks stressed that, because of AI technology, editors must now verify all photo and video submissions to avoid spreading misinformation.

Every photo and video organizations receive – from politicians, corporations, public relations practitioners, foreign governments, activists or just regular folks – is an opportunity to misinform the public.

CLOSING REVIEW

WRITE ABOUT IT

Answer each question in approximately five sentences. When possible, strengthen your responses with brief supporting content from this chapter.

1. Do you think the chapter’s examples about Monica Crowley meet the definition of plagiarism? Are you sympathetic to her view that she is the victim of a political hit job? Explain the reasons for your conclusion.

2. Revisit the linked content about photo tampering throughout history. Find an example of photo tampering that you think fits the description of fabrication discussed in this chapter. Include the year and a brief summary of the case, and then tell why you think this example is particularly egregious.

3. Cite a key takeaway you gained from assigned readings about how fake news grabs our attention:

The psychology of misinformation: Why we’re vulnerable

Discuss implications for newsroom journalists who want to gain a large audience but remain ethical in doing so.

4. Based on chapter content, why is the philosophical term bullshit an appropriate metaphor for text generated by large language models such as ChatGPT?

5. Read the following scenario:

You are a PR writer for a technology company. A local newspaper has begun publishing your PR releases online with no byline or acknowledgment of the source. On one hand, this is great for your company because it delivers information to the public exactly the way you want that information delivered — without any editorial changes. On the other hand, you start to feel uneasy about the situation because you took a journalism ethics course in college, and you suspect that the newspaper’s word-for-word publication may fit within the formal definition of plagiarism.

Would you notify the local newspaper with your concerns? Do you think that press releases need a clear attribution? What are your suggested parameters?