16 Negotiating Power in Groups

Learning Objectives

- Explain different conceptualizations of power

- Describe the relationship between power and oppression

- Discuss behaviors associated with high status in a group

- Differentiate between the common power bases in groups

- Discuss what it means to exercise power ethically

Given the complexity of group interaction, it is short-sighted to try to understand group communication without looking at notions of power. Power influences how we interpret the messages of others and determines the extent to which we feel we have the right to speak up and voice our concerns and opinions to others. Power and status are key ways that people exercise influence within groups. In the storming phase of group development, members are likely to engage in more obvious power struggles, but power is constantly at work in our interactions within and outside our group whether we are fully conscious of it or not. In this chapter, we will define power and discuss its relationship to broader systems in which we may operate, and status within groups. We will also discuss the bases and tactics of power that can operate in groups and teams, as well as the ethical use of power.

Defining Power

Take a moment to reflect on the different ways you think about power. What images come to mind for you when you think of power? Are there different kinds of power? Are some people inherently more powerful than others? Do you consider yourself to be a powerful person? We highlight three ways to understand power as it relates to group and team communication. The word “power” literally means “to be able” and has many implications.

If you associate power with control or dominance, this refers to the notion of power as power-over. According to Starhawk (1987), “power-over enables one individual or group to make the decisions that affect others, and to enforce control” (p. 9). Control can and does take many forms in society. Starhawk explains that,

This power is wielded from the workplace, in the schools, in the courts, in the doctor’s office. It may rule with weapons that are physical or by controlling the resources we need to live: money, food, medical care; or by controlling more subtle resources: information, approval, love. We are so accustomed to power-over, so steeped in its language and its implicit threats, that we often become aware of its functioning only when we see its extreme manifestations. (p. 9)

When we are in group situations and someone dominates the conversation, makes all of the decisions, or controls the resources of the group such as money or equipment, this is power-over.

Power-from-within refers to a more personal sense of strength or agency. Power-from-within manifests itself when we can stand, walk, and speak “words that convey our needs and thoughts” (Starhawk, 1987, p. 10). In groups, this type of power “arises from our sense of connection, our bonding with other human beings, and with the environment” (10). As Heider explains in The Tao of Leadership, “Since all creation is a whole, separateness is an illusion. Like it or not, we are team players. Power comes through cooperation, independence through service, and a greater self through selflessness” (77). If you think about your role in groups, how have you influenced other group members? Your strategies indicate your sense of power-from-within.

Finally, groups manifest power-with, which is “the power of a strong individual in a group of equals, the power not to command, but to suggest and be listened to, to begin something and see it happen” (Starhawk, 1987, p. 10). For this to be effective in a group or team, at least two qualities must be present among members: (1) all group members must communicate respect and equality for one another, and (2) the leader must not abuse power-with and attempt to turn it into power-over. Have you ever been involved in a group where people did not treat each other as equals or with respect? How did you feel about the group? What was the outcome? Could you have done anything to change that dynamic?

UNDERSTANDING POWER AND OPPRESSION

Power and oppression can be said to be mirror reflections of one another in a sense or two sides of the same coin. Where you see power that causes harm, you will likely see oppression. Oppression is defined in Merriam-Webster dictionary as: “Unjust or cruel exercise of authority or power especially by the imposition of burdens; the condition of being weighed down; an act of pressing down; a sense of heaviness or obstruction in the body or mind.” This definition demonstrates the intensity of oppression, which also shows how difficult such a challenge is to address or eradicate. Further, the word oppression comes from the Latin root primere, which actually means “pressed down”. Importantly, we can conclude that oppression is the social act of placing severe restrictions on an individual, group, or institution.

Oppression emerges as a result of power, with its roots in global colonialism and conquests. For example, oppression as an action can deny certain groups jobs that pay living wages, can establish unequal education (e.g., through a lack of adequate capital per student for resources), can deny affordable housing, and the list goes on. You may be wondering why some groups live in poverty, reside in substandard housing, or simply do not ‘measure up’ to the dominant society in some facet. As discussed at a seminar at the Leaven Center (2003), groups that do not have “power over” are those society classifies or labels as disenfranchised; they are often exploited and victimized in a variety of ways. They may be subjected to restrictions and seen as expendable and replaceable. This philosophy, in turn, minimizes the roles certain populations play in society. As a result, people often deny that this injustice occurs and blame oppressive conditions on the behaviors and actions of the oppressed group.

Oppression subsequently becomes a system as patterns are adopted and perpetuated. Systems of oppression discriminate or advantage based on perceived or real differences among people. Socialization patterns help maintain such systems. Through formal and informal education, engagement with media, and communication with and observations of others around them, people learn who and what is valued, how they should act, and what their role and place are in society.

So what do these systems mean for groups? Members in groups do not leave their identities or social and cultural contexts at the door. Power and status in groups are still shaped by these broader systems that are external to the group. This requires group members to reflect on how these systems are shaping dynamics within the group and their own perceptions and behaviors.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN Power and Status

One way that these dynamics can play out in groups is related to a group member’s status. Status can be defined as a person’s perceived level of importance or significance within a particular context. Those who have status tend to experience privileges. In a group, members with higher status are apt to command greater respect and possess more prestige and power than those with lower status.

Our status is often tied to our identities and their perceived value within our social and cultural context. Groups may confer status upon their members based on their age, wealth, gender, race or ethnicity, ability, physical stature, perceived intelligence, and/or other attributes. Status can also be granted through title or position. In professional circles, for instance, having earned a “terminal” degree such as a Ph.D. or M.D. usually generates a degree of status. The same holds true for the documented outcomes of schooling or training in legal, engineering, or other professional fields. Likewise, people who’ve been honored for achievements in any number of areas may bring status to a group by virtue of that recognition if it relates to the nature and purpose of the group. Once a group has formed and begun to sort out its norms, it will also build upon the initial status that people bring to it by further allocating status according to its own internal processes and practices. For instance, choosing a member to serve as an officer in a group generally conveys status to that person.

Let’s say you’ve either come into a group with high status or have been granted high status by the other members. What does this mean to you, and how are you apt to behave? Here are some predictions based on research from several sources (Beebe & Masterson, 2015; Borman, 1989; Brilhart & Galanes, 1997; Homans, 1992).

First, the volume and direction of your speech will differ from those of others in the group. You’ll talk more than the low-status members do, and you’ll communicate more with other high-status members than you will with lower-status individuals. In addition, you’ll be more likely to speak to the whole group than will members with lower status.

Second, some indicators of your participation will be particularly positive. Your activity level and self-regard will surpass those of lower-status group members. So will your level of satisfaction with your position. Furthermore, the rest of the group is less likely to ignore your statements and proposals than it is to disregard what lower-status individuals say.

Finally, the content of your communication will probably be different from what your fellow members discuss. Because you may have access to special information about the group’s activities and may be expected to shoulder specific responsibilities because of your position, you’re apt to talk about topics that are relevant to the central purposes and direction of the group. Lower-status members, on the other hand, are likely to communicate more about other matters.

There’s no such thing as a “status neutral” group—one in which everyone always has the same status as everyone else. Differences in status within a group are inevitable and can be dangerous if not recognized and managed. For example, someone who gains status without possessing the skills or attributes required to use it well may cause real damage to other members of a group, or a group as a whole. A high-status, low-ability person may develop an inflated self-image, begin to abuse power, or both. One of us worked for the new president of a college who acted as though his position entitled him to take whatever actions he wanted. In the process of interacting primarily with other high-status individuals who shared the majority of his viewpoints and goals, he overlooked or rejected concerns and complaints from people in other parts of the organization. Turmoil and dissension broke out. Morale plummeted. The president eventually suffered votes of no confidence from his college’s faculty, staff, and students and was forced to resign.

Bases of Power in GROUPS

Within groups, there are several different ways in which power can operate. French and Raven (1968) identified five primary ways in which power can be exerted in social situations, including in groups and teams. These are considered to be different bases of power.

Referent Power

In some cases, person B looks up to or admires person A, and, as a result, B follows A largely because of A’s personal qualities, characteristics, or reputation. In this case, A can use referent power to influence B. Referent power has also been called charismatic power, because allegiance is based on the interpersonal attraction of one individual for another. Examples of referent power can be seen in advertising, where companies use celebrities to recommend their products; it is hoped that the star appeal of the person will rub off on the products. In work environments, junior managers often emulate senior managers and assume unnecessarily subservient roles more because of personal admiration than because of respect for authority.

Expert Power

Expert power is demonstrated when person A gains power because A has knowledge or expertise relevant to B. For instance, professors presumably have power in the classroom because of their mastery of a particular subject matter. Other examples of expert power can be seen in staff specialists in organizations (e.g., accountants, labor relations managers, management consultants, and corporate attorneys). In each case, the individual has credibility in a particular—and narrow—area as a result of experience and expertise, and this gives the individual power in that domain.

Legitimate Power

Legitimate power exists when person B submits to person A because B feels that A has a right to exert power in a certain domain (Tjosvold, 1985). Legitimate power is really another name for authority. A supervisor has a right, for instance, to assign work. Legitimate power differs from reward and coercive power in that it depends on the official position a person holds, and not on his or her relationship with others.

Reward Power

Reward power exists when person A has power over person B because A controls rewards that B wants. These rewards can cover a wide array of possibilities, including pay raises, promotions, desirable job assignments, more responsibility, new equipment, and so forth. Research has indicated that reward power often leads to increased job performance as employees see a strong performance-reward contingency (Shetty, 1978). However, in many organizations, supervisors and managers really do not control very many rewards. For example, salary and promotion among most blue-collar workers is based on a labor contract, not a performance appraisal.

Coercive Power

Coercive power is based primarily on fear. Here, person A has power over person B because A can administer some form of punishment to B. Thus, this kind of power is also referred to as punishment power. As Kipnis (1976) points out, coercive power does not have to rest on the threat of violence. “Individuals exercise coercive power through a reliance upon physical strength, verbal facility, or the ability to grant or withhold emotional support from others. These bases provide the individual with the means to physically harm, bully, humiliate, or deny love to others.” Examples of coercive power in organizations include the ability (actual or implied) to fire or demote people, transfer them to undesirable jobs or locations, or strip them of valued perquisites. Indeed, it has been suggested that a good deal of organizational behavior (such as prompt attendance, looking busy, avoiding whistle-blowing) can be attributed to coercive, not reward, power. As Kipnis (1976) explains, “Of all the bases of power available to man, the power to hurt others is possibly the most often used, most often condemned and most difficult to control.”

Consequences of Power

We have seen, then, that at least five bases of power can be identified. In each case, the power of the individual rests on a particular attribute of the power holder, the follower, or their relationship. In some cases (e.g., reward power), power rests in the superior; in others (e.g., referent power), power is given to the superior by the subordinate. In all cases, the exercise of power involves subtle and sometimes threatening interpersonal consequences for the parties involved. In fact, when power is exercised, individuals have several ways in which to respond. These are shown in Figure 1.

If the subordinate accepts and identifies with the leader, their behavioral response will probably be one of commitment. That is, the subordinate will be motivated to follow the wishes of the leader. This is most likely to happen when the person in charge uses referent or expert power. Under these circumstances, the follower believes in the leader’s cause and will exert considerable energies to help the leader succeed.

A second possible response is compliance. This occurs most frequently when the subordinate feels the leader has either legitimate power or reward power. Under such circumstances, the follower will comply, either because it is perceived as a duty or because a reward is expected; but commitment or enthusiasm for the project is lacking. Finally, under conditions of coercive power, subordinates will more than likely use resistance. Here, the subordinate sees little reason—either altruistic or material—for cooperating and will often engage in a series of tactics to defeat the leader’s efforts.

Power Dependencies

In any situation involving power, at least two persons (or groups) can be identified: (1) the person attempting to influence others and (2) the target or targets of that influence. Until recently, attention focused almost exclusively on how people tried to influence others. More recently attention has been given to how people try to nullify or moderate such influence attempts. In particular, we now recognize that the extent to which influence attempts are successful is determined in large part by the power dependencies of those on the receiving end of the influence attempts. In other words, all people are not subject to (or dependent upon) the same bases of power. What causes some people to be vulnerable to power attempts? At least three factors have been identified (Mitchell & Larson, 1988).

Subordinate’s Values

To begin, person B’s values can influence his susceptibility to influence. For example, if the outcomes that A can influence are important to B, then B is more likely to be open to influence than if the outcomes were unimportant. Hence, if an employee places a high value on money and believes the supervisor actually controls pay raises, we would expect the employee to be highly susceptible to the supervisor’s influence. We hear comments about how young people don’t really want to work hard anymore. Perhaps a reason for this phenomenon is that some young people don’t place a high value on those things (for example, money) that traditionally have been used to influence behavior. In other words, such complaints may really be saying that young people are more difficult to influence than they used to be.

Nature of Relationship

In addition, the nature of the relationship between A and B can be a factor in power dependence. Are A and B peers or superior and subordinate? Is the job permanent or temporary? A person on a temporary job, for example, may feel less need to acquiesce, because he won’t be holding the position for long. Moreover, if A and B are peers or good friends, the influence process is likely to be more delicate than if they are superior and subordinate.

Counterpower

Finally, a third factor to consider in power dependencies is counterpower. The concept of counterpower focuses on the extent to which B has other sources of power to buffer the effects of A’s power. For example, if B is unionized, the union’s power may serve to negate A’s influence attempts. The use of counterpower can be clearly seen in a variety of situations where various coalitions attempt to bargain with one another and check the power of their opponents.

Figure 2 presents a rudimentary model that combines the concepts of bases of power with the notion of power dependencies. As can be seen, A’s bases of power interact with B’s extent of power dependency to determine B’s response to A’s influence attempt. If A has significant power and B is highly dependent, we would expect B to comply with A’s wishes.

If A has more modest power over B, but B is still largely power dependent, B may try to bargain with A. Despite the fact that B would be bargaining from an unstable/weaker position, this strategy may serve to protect B’s interests better than outright compliance. For instance, if your boss asked you to work overtime, you might attempt to strike a deal whereby you would get compensatory time off at a later date. If successful, although you would not have decreased your working hours, at least you would not have increased them. Where power distribution is more evenly divided, B may attempt to develop a cooperative working relationship with A in which both parties gain from the exchange. An example of this position is a labor contract negotiation where labor-management relations are characterized by a balance of power and a good working relationship.

If B has more power than A, B will more than likely reject A’s influence attempt. B may even become the aggressor and attempt to influence A. Finally, when B is not certain of the power relationships, he may simply try to ignore A’s efforts. In doing so, B will discover either that A does indeed have more power or that A cannot muster the power to be successful. A good illustration of this last strategy can be seen in some companies’ responses to early governmental efforts to secure equal opportunities for minorities and women. These companies simply ignored governmental efforts until new regulations forced compliance.

Uses of Power

As we look at our groups and teams as well as our organizations, it is easy to see manifestations of power almost anywhere. In fact, there are a wide variety of power-based methods used to influence others. Here, we will examine two aspects of the use of power: commonly used power tactics and the ethical use of power.

Common Power Tactics in Organizations

As noted above, many power tactics are available for use. However, as we will see, some are more ethical than others. Here, we look at some of the more commonly used power tactics found in both business and public organizations (Pfeffer, 2011) that also have relevance for groups.

Controlling Access to Information

Most decisions rest on the availability of relevant information, so persons controlling access to information play a major role in decisions made. A good example of this is the common corporate practice of pay secrecy. Only the personnel department and senior managers typically have salary information—and power—for personnel decisions.

Controlling Access to Persons

Another related power tactic is the practice of controlling access to persons. A well-known factor contributing to President Nixon’s downfall was his isolation from others. His two senior advisers had complete control over who saw the president. Similar criticisms were leveled against President Reagan.

Selective Use of Objective Criteria

Very few questions have one correct answer; instead, decisions must be made concerning the most appropriate criteria for evaluating results. As such, significant power can be exercised by those who can practice selective use of objective criteria that will lead to a decision favorable to themselves. According to Herbert Simon, if an individual is permitted to select decision criteria, then that person needn’t care who actually makes the decision. Attempts to control objective decision criteria can be seen in faculty debates in a university or college over who gets hired or promoted. One group tends to emphasize teaching and will attempt to set criteria for employment dealing with teacher competence, subject area, interpersonal relations, and so on. Another group may emphasize research and will try to set criteria related to the number of publications, reputation in the field, and so on.

Controlling the Agenda

One of the simplest ways to influence a decision is to ensure that it never comes up for consideration in the first place. There are a variety of strategies used for controlling the agenda. Efforts may be made to order the topics at a meeting in such a way that the undesired topic is last on the list. Failing this, opponents may raise several objections or points of information concerning the topic that cannot be easily answered, thereby tabling the topic until another day.

Using Outside Experts

Still, another means to gain an advantage is using outside experts. The unit wishing to exercise power may take the initiative and bring in experts from the field or experts known to be in sympathy with their cause. Hence, when a dispute arises over spending more money on research versus actual production, we would expect differing answers from outside research consultants and outside production consultants. Most consultants have experienced situations in which their clients fed them information and biases they hoped the consultant would repeat in a meeting.

Bureaucratic Gamesmanship

In some situations, the organization’s own policies and procedures provide ammunition for power plays, or bureaucratic gamesmanship. For instance, a group may drag its feet on making changes in the workplace by creating red tape, work slowdowns, or “work to rule.” (Working to rule occurs when employees diligently follow every work rule and policy statement to the letter; this typically results in the organization’s grinding to a halt as a result of the many and often conflicting rules and policy statements.) In this way, the group lets it be known that the workflow will continue to slow down until they get their way.

Coalitions and Alliances

The final power tactic to be discussed here is that of coalitions and alliances. One unit can effectively increase its power by forming an alliance with other groups that share similar interests. This technique is often used when multiple labor unions in the same corporation join forces to gain contract concessions for their workers. It can also be seen in the tendency of corporations within one industry to form trade associations to lobby for their position. Although the various members of a coalition need not agree on everything—indeed, they may be competitors—sufficient agreement on the problem under consideration is necessary as a basis for action.

Ethical Use of Power

Several guidelines for the ethical use of power can be identified. These can be arranged according to our previous discussion of the five bases of power, as shown in Table 1. As will be noted, several techniques are available that accomplish their aims without compromising ethical standards. For example, a person using reward power can verify compliance with work directives, ensure that all requests are both feasible and reasonable, make only ethical or proper requests, offer rewards that are valued, and ensure that all rewards for good performance are credible and reasonably attainable.

| Table 1: The Ethical Use of Power |

|

| Basis of Power | Guidelines for Use |

| Referent power |

|

| Expert power |

|

| Legitimate power |

|

| Reward power |

|

| Coercive power |

|

| Credit: Rice University/Openstax/CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Source: Adapted from Yukl (2013). | |

Even coercive power can be used without jeopardizing personal integrity. For example, a manager can make sure that all employees know the rules and penalties for rule infractions, provide warnings before punishing, administer punishments fairly and uniformly, and so forth. The point here is that people have at their disposal numerous tactics that they can employ without abusing their power.

Review & Reflection Questions

- Before reading the chapter, how did you define power? How might power-to, power-from-within, and power-with make us think about power differently?

- What is the relationship between power and oppression?

- When you first joined your group, what assumptions did you make about the status of different members? Where did those assumptions come from?

- Identify five bases of power, and provide an example of each. Which base (or bases) of power do you feel would be most commonly found in groups?

- How can we exercise power ethically? What might be some best practices in the context of your group?

References

- Beebe, S.A., & Masterson, J.T. (2015). Communicating in small groups: Principles and practices (11th ed.). Pearson.

- Borman, E.G. (1989). Discussion and group methods: Theory and practice (3rd ed.). Harper and Row.

- Brilhart,J.K., & Galanes, G.J. (1997). Effective group discussion. Brown.

- French, J., & Raven, B. (1968). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright and A. Zander (Eds.), Group Dynamics. Harper & Row.

- Heider, J. (2005). The Tao of Leadership: Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching Adapted for a New Age (1st ed.) Green Dragon.

- Homans, G.C. (1992). The human group. Harcourt Brace & World.

- Kipnis, D. (1976). The Powerholders. University of Chicago Press.

- Leaven Center (2003). Doing Our Own Work: A Seminar for Anti-Racist White Women. Visions, Inc. and the MSU Extension Multicultural Awareness Workshop.

- Mitchell, T. R., & Larson, J. (1988). People in organizations. McGraw-Hill.

- Shetty, Y. (1978). Managerial power and organizational effectiveness: A contingency analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 15, 178–181.

- Starhawk (1987). Truth or dare: Encounters with power authority, and mystery. Harper.

- Thai, N. D. & Lien, A. (2019). Respect for diversity. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/respect-for-diversity/

- Tjosvold, D. (1985). Power and social context in the superior-subordinate interaction,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 281–293.

- Yukl, G. A. (2013). Leadership in 0rganizations (8th ed.). Pearson.

Author and Attribution

The introduction and the section “Defining Power” are adapted from Chapter 10 “Groups Communication” from Survey of Communication Study by Laura K. Hawn and Scott T. Paynton. This content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

The section “Relationship between Power and Status” is adapted from “Status” from An Introduction To Group Communication. This content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

The sections “Bases of Power” and “Uses of Power” are adapted from “Organizational Power and Politics” Black, J.S., & Bright, D.S. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/. Access the full chapter for free here. The content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license.

The section “Understanding Power and Oppression” is adapted from Palmer, G.L, Ferńandez, J. S., Lee, G., Masud, H., Hilson, S., Tang, C., Thomas, D., Clark, L., Guzman, B., & Bernai, I. Oppression and power. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology. Pressbooks. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/. The content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License.

Learning Objectives

- Identify situations where you may need to enact different leadership styles or strategies based on the context and needs of your group

- Distinguish between transactional and transformative leaders

- Identify the four characteristics of transformative leaders

In the previous chapter, you were introduced to definitions of leaders and leadership and to the various ways leaders are identified and emerge in groups. In this chapter, we will dive deeper into two specific theories and approaches to leadership relevant to groups and teams, specifically situational leadership and transformational leadership.

Situational Leadership

Situational leadership, or leadership in context, means that leadership itself depends on the situation at hand. In sharp contrast to the idea of a “natural born leader” found in traits approaches to leadership, this viewpoint is relativist. Leadership is relative or varies, based on the context. There is no one “universal trait” to which we can point or principle to which we can observe in action. No style of leadership is more or less effective than another unless we consider the context. Then our challenge presents itself: how to match the most effective leadership strategy with the current context?

To match leadership strategies and context we first need to discuss the range of strategies as well as the range of contexts. While the strategies list may not be as long as we might imagine, the context list could go on forever. If we were able to accurately describe each context, and discuss each factor, we would quickly find the task led to more questions, more information, and the complexity would increase, making an accurate description or discussion impossible. Instead, we can focus our efforts on factors that each context contains and look for patterns, or common trends, that help us make generalizations about our observations.

For example, an emergency may require a leader to be direct, giving specific orders to each person. Since each second counts, the quick thinking and actions at the direction of a leader may be the most effective strategy. To stop and discuss, vote, or check everyone’s feelings on the current emergency situation may waste valuable time. That same approach applied to common governance or law-making may indicate a dictator is in charge, and that individuals and their vote are of no consequence. Instead, an effective leader in a democratic process may ask questions, gather viewpoints, and seek common ground as lawmakers craft a law that applies to everyone equally.

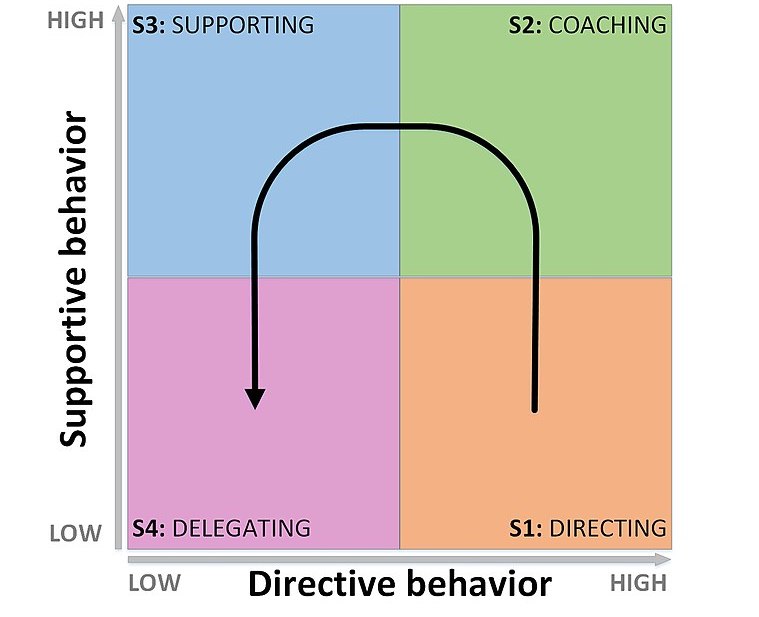

Hersey and Blanchard Model of Situational Leadership

Hersey and Blanchard (1977) take the situational framework and apply it to an organizational perspective that reflects our emphasis on group communication. They assert that to be an effective manager, one needs to change their leadership style based on the context, including the skills, knowledge, and motivation of the people they are leading and the task details. Hersey and Blanchard focus on two key issues: tasks and relationships, and present the idea that we can to a greater or lesser degree focus on one or the other to achieve effective leadership in a given context. They offer four distinct leadership styles or strategies (abbreviated with an “S”):

- Directing (S1). Leaders tell people what to do and how to do it.

- Coaching (S2). Leaders provide direction, information, and guidance, but sell their message to gain compliance among group members.

- Supporting (S3). Leaders focus on the relationships with group members and shares decision-making responsibilities with them.

- Delegating (S4). Leaders focus on relationships, rely on professional expertise or group member skills, and monitor progress. They allow group members to be more directly responsible for individual decisions but may still participate in the process.

Directing and coaching strategies are all about getting the task done. Supporting and delegating styles are about developing relationships and empowering group members to get the job done. Each style or approach is best suited, according to Hersey and Blanchard, to a specific context. Again, assessing a context can be a challenging task but they indicate the focus should be on the development level of the group members. It is a responsibility of the leader to assess the group members and the degree to which they possess the ability to work independently or together effectively, including whether they have the competence, or the right combination of skills and abilities that the task requires, as well as the commitment or motivation to complete the task. Once again, they offer us four distinct levels (abbreviated with “D” for development):

- D1, or level one (low competence and high commitment). This is the most basic level where group members lack the skills, prior knowledge, skills, or self-confidence to accomplish the task effectively. They need specific directions, and systems of rewards and punishment (for failure) may be featured. They will need external motivation from the leader to accomplish the task.

- D2, or level two (some competence and low commitment) At this level the group members may possess the motivation, or the skills and abilities, but not both. They may need specific, additional instructions or may require external motivation to accomplish the task.

- D3, or level three (high competence and some commitment). At this level we can observe group members who are ready to accomplish the task, are willing to participate, but may lack confidence or direct experience, requiring external reinforcement and some supervision.

- D4, or level four (high competence and high commitment). Finally, we can observe group members that are ready, prepared, willing, and confident in their ability to solve the challenge or complete the task. They require little supervision.

Now it is our task to match the style or leadership strategy to the development level of the group members as shown in the table below.

| Leadership Style (S) | Development Level (D) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | S1 | D1 |

| 2 | S2 | D2 |

| 3 | S3 | D3 |

| 4 | S4 | D4 |

This is one approach to situational leadership that applies to our exploration of group communication, but it does not represent all approaches. What other factors might you consider? How might we assess diversity, for example, in this approach? We might have a skilled professional who speaks English as their second language, and who comes from a culture where constant supervision is viewed as controlling or domineering, and if a leader takes an S1 approach to provide leadership, we can anticipate miscommunication and even frustration. The effective group communicator recognizes the Hersey-Blanchard approach provides insight and possible solutions to consider but also keeps the complexity of the context in mind when considering a course of action.

Path-Goal Theory

A second situational leadership theory comes from Robert J. House and Martin Evans. Like Hersey and Blanchard, they assert that the type of leadership needed to enhance organizational effectiveness depends on the situation in which the leader is placed.

The model of leadership advanced by House and Evans is called the path-goal theory of leadership because it suggests that an effective leader provides organizational members with a path to a valued goal. According to House (1971), the motivational function of the leader consists of increasing personal payoffs to organizational members for work-goal attainment, and making the path to these payoffs easier to travel by clarifying it, reducing roadblocks and pitfalls, and increasing the opportunities for personal satisfaction en route.

Effective leaders, therefore, provide rewards that are valued by group members. In an organization, these rewards may be pay, recognition, promotions, or any other item that gives members an incentive to work hard to achieve goals. Effective leaders also give clear instructions so that ambiguities about work are reduced and followers understand how to do their jobs effectively. They provide coaching, guidance, and training so that followers can perform the task expected of them. They also remove barriers to task accomplishment, correcting shortages of materials, inoperative machinery, or interfering policies.

According to the path-goal theory, the challenge facing leaders is basically twofold. First, they must analyze situations and identify the most appropriate leadership style. For example, experienced employees who work on a highly structured assembly line don’t need a leader to spend much time telling them how to do their jobs—they already know this. The leader of an archeological expedition, though, may need to spend a great deal of time telling inexperienced laborers how to excavate and care for the relics they uncover.

Second, leaders must be flexible enough to use different leadership styles as appropriate. To be effective, leaders must engage in a wide variety of behaviors. Without an extensive repertoire of behaviors at their disposal, a leader’s effectiveness is limited (Hoojiberg, 1996). All team members will not, for example, have the same need for autonomy. The leadership style that motivates organizational members with strong needs for autonomy (participative leadership) is different from that which motivates and satisfies members with weaker autonomy needs (directive leadership). The degree to which leadership behavior matches situational factors will determine members’ motivation, satisfaction, and performance (see Figure 1; House & Dessler, 1974; House & Mitchell, 1974).

According to path-goal theory, there are four important dimensions of leader behavior, each of which is suited to a particular set of situational demands (House & Dessler, 1974; House & Mitchell, 1974; Keller, 1989).

- Supportive leadership—At times, effective leaders demonstrate concern for the well-being and personal needs of organizational members. Supportive leaders are friendly, approachable, and considerate to individuals in the workplace. Supportive leadership is especially effective when an organizational member is performing a boring, stressful, frustrating, tedious, or unpleasant task. If a task is difficult and a group member has low self-esteem, supportive leadership can reduce some of the person’s anxiety, increase his confidence, and increase satisfaction and determination as well.

- Directive leadership—At times, effective leaders set goals and performance expectations, let organizational members know what is expected, provide guidance, establish rules and procedures to guide work, and schedule and coordinate the activities of members. Directive leadership is called for when role ambiguity is high. Removing uncertainty and providing needed guidance can increase members’ effort, job satisfaction, and job performance.

- Participative leadership—At times, effective leaders consult with group members about job-related activities and consider their opinions and suggestions when making decisions. Participative leadership is effective when tasks are unstructured. Participative leadership is used to great effect when leaders need help in identifying work procedures and where followers have the expertise to provide this help.

- Achievement-oriented leadership—At times, effective leaders set challenging goals, seek improvement in performance, emphasize excellence, and demonstrate confidence in organizational members’ ability to attain high standards. Achievement-oriented leaders thus capitalize on members’ needs for achievement and use goal-setting theory to great advantage.

Overall, there is no “One Size Fits All” leadership approach that works for every context, but the situational leadership viewpoint reminds us of the importance of being in the moment and assessing our surroundings, including our group members and their relative strengths and areas of emerging skill.

Transformational Leadership

Our second approach, transformational leadership, emphasizes the vision, mission, motivations, and goals of a group or team and motivates them to accomplish the task or achieve the result. This model of leadership asserts that people will follow a person who inspires them, who clearly communicates their vision with passion, and helps get things done with energy and enthusiasm.

James MacGregor Burns (1978), a presidential biographer, first introduced the concept, discussing the dynamic relationship between the leader and the followers, as they together motivate and advance towards the goal or objective. Bass (1985) contributed to his theory, suggesting there are four key components of transformation leadership:

- Idealized Influence: Transformational leaders serve as role models, demonstrating expertise, skills, and talent that others seek to emulate, inspiring positive actions while reinforcing trust and respect.

- Inspirational Motivation: Transformational leaders communicate a clear vision, helping followers understand the individual steps necessary to accomplish the task or objective while sharing in the anticipation of completion.

- Individualized Consideration: Transformational leaders recognize and celebrate each follower’s unique contributions to the group.

- Intellectual stimulation: Transformational leaders encourage creativity and ingenuity, challenging the status quo, and encouraging followers to explore new approaches and opportunities.

The leader conveys the group’s goals and aspirations, displays a passion for the challenge that lies ahead, and demonstrates a contagious enthusiasm that motivates group members to succeed. This approach focuses on the positive changes that need to occur for the group to be successful and requires the leader to be energetic and involved with the process, even helping individual members complete their respective roles or tasks.

Transformational leadership is considered to be distinct from transactional models of leadership. Bryman (1992) wrote that transactional leaders exchange rewards for performance. Transformational leaders, by contrast, provide group members with a vision to which they can all aspire. They also work to develop a team spirit so that it becomes possible to achieve that vision.

Den Hartog, Van Muijen, and Kopman (1997) distinguished clearly between these two kinds of leaders. They held that transactional leaders motivate group members to perform as expected, whereas transformational leaders inspire followers to achieve more than what is expected. Nanus (1992) wrote that transformational leaders accomplish these tasks by instilling pride and generating respect and trust; by communicating high expectations and expressing important goals in straightforward language; by promoting rational, careful problem-solving; and by devoting personal attention to group members.

Review & Reflection Questions

- Should our approach to leadership depend on the context? Why or why not?

- Using the two different theories of situational leadership, what leadership styles or strategies might be appropriate to use in your group? Why?

- What is the difference between a transactional and a transformational leader? What examples of transformational leadership have you observed?

References

- Bass, B. (1985). Leadership and performance. Free Press.

- Bryman, A. (1992). Charisma and leadership in organizations. Sage.

- Burns, J. (1978). Leadership. Harper and Row.

- Den Hartog, D.N., Van Muijen, J.J., & Kopman, P.L. (1997). Transactional versus transformational leadership: An analysis of the MLQ (Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire). Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70, 19–35.

- Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1977). Management of organizational behavior (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Hoojiberg, R. (1996). A multidimensional approach toward leadership: An extension of the concept of behavioral complexity. Human Relations, 49(7), 917–946.

- House, R. J. (1971). A path-goal theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16, 321–333.

- House, R. J., & Dessler, G. (1974). The path-goal theory of leadership: Some post hoc and a priori tests. In J. Hunt & L. Larson (eds.). Contingency approaches to leadership. Southern Illinois University Press.

- House, R. J., & Mitchell, T. R. (1974). Path-goal theory of leadership, Journal of Contemporary Business, 5, 81-94.

- Keller, R. T. (1989). A test of the path-goal theory of leadership with need for clarity as a moderator in research and development organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 208–212.

- Nanus, D. (1992). Visionary leadership: Creating a compelling sense of direction for your organization. Jossey-Bass.

Authors & Attribution

The majority of the content in this chapter is adapted and remixed from "Group Leadership" from An Introduction To Group Communication. This content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) License without attribution as requested by the work's original creator or licensor.

The section on "Path-Goal Theory" in this chapter was adapted from Bright, D.S., & Cortes, A. H. (2019). Principles of management. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/principles-management. Access the full chapter for free here. The content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license.

Learning Objectives

- Define small group communication

- Discuss the characteristics of small groups

- Compare and contrast different types of small groups

- Describe the advantages and disadvantages of small groups

- Describe the key principles of the Bona Fide Group Perspective

Small group communication refers to interactions among three or more people who are connected through a common purpose, mutual influence, and a shared identity. In this chapter, we will provide an overview of the characteristics and types of small groups and discuss their advantages and disadvantages.

Characteristics of Small Groups

Different groups have different characteristics, serve different purposes, and can lead to positive, neutral, or negative experiences. While our interpersonal relationships primarily focus on relationship building, small groups usually focus on some sort of task completion or goal accomplishment. A college learning community focused on math and science, a campaign team for a state senator, and a group of local organic farmers are examples of small groups that would all have a different size, structure, identity, and interaction pattern.

Size of Small Groups

There is no set number of members for the ideal small group. A small group requires a minimum of three people (because two people would be a pair or dyad), but the upper range of group size is contingent on the purpose of the group. When groups grow beyond fifteen to twenty members, it becomes difficult to consider them a small group based on the previous definition. An analysis of the number of unique connections between members of small groups shows that they are deceptively complex. For example, within a six-person group, there are fifteen separate potential dyadic connections, and a twelve-person group would have sixty-six potential dyadic connections (Hargie, 2011). As you can see, when we double the number of group members, we more than double the number of connections, which shows that network connection points in small groups grow exponentially as membership increases. So, while there is no set upper limit on the number of group members, it makes sense that the number of group members should be limited to those necessary to accomplish the goal or serve the purpose of the group. Small groups that add too many members increase the potential for group members to feel overwhelmed or disconnected.

Structure of Small Groups

Internal and external influences affect a group’s structure. In terms of internal influences, member characteristics play a role in initial group formation. For instance, a person who is well informed about the group’s task and/or highly motivated as a group member may emerge as a leader and set into motion internal decision-making processes, such as recruiting new members or assigning group roles, that affect the structure of a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Different members will also gravitate toward different roles within the group and will advocate for certain procedures and courses of action over others. External factors such as group size, task, and resources also affect group structure. Some groups will have more control over these external factors through decision making than others. For example, a commission that is put together by a legislative body to look into ethical violations in athletic organizations will likely have less control over its external factors than a self-created weekly book club.

Group structure is also formed through formal and informal network connections. In terms of formal networks, groups may have clearly defined roles and responsibilities or a hierarchy that shows how members are connected. The group itself may also be a part of an organizational hierarchy that networks the group into a larger organizational structure. This type of formal network is especially important in groups that have to report to external stakeholders. These external stakeholders may influence the group’s formal network, leaving the group little or no control over its structure. Conversely, groups have more control over their informal networks, which are connections among individuals within the group and among group members and people outside of the group that aren’t official. For example, a group member’s friend or relative may be able to secure a space to hold a fundraiser at a discounted rate, which helps the group achieve its task. Both types of networks are important because they may help facilitate information exchange within a group and extend a group’s reach in order to access other resources.

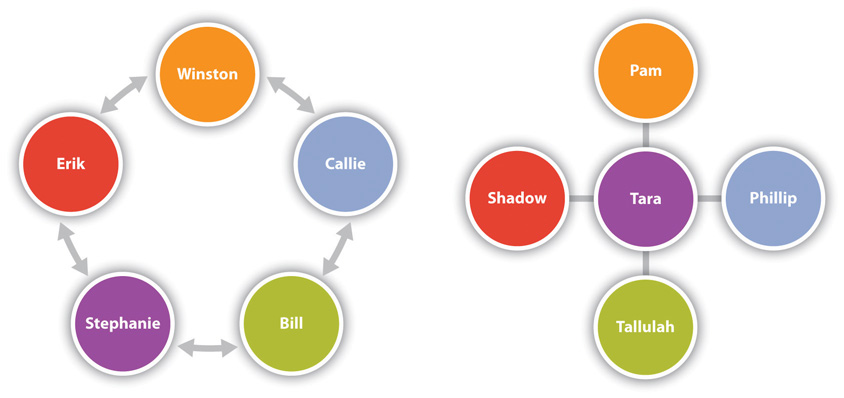

Size and structure also affect communication within a group (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). In terms of size, the more people in a group, the more issues with scheduling and coordination of communication. Remember that time is an important resource in most group interactions and a resource that is usually strained. Structure can increase or decrease the flow of communication. Reachability refers to the way in which one member is or isn’t connected to other group members. For example, the “Circle” group structure in Figure 1 shows that each group member is connected to two other members. This can make coordination easy when only one or two people need to be brought in for a decision. In this case, Erik and Callie are very reachable by Winston, who could easily coordinate with them. However, if Winston needed to coordinate with Bill or Stephanie, he would have to wait on Erik or Callie to reach that person, which could create delays. The circle can be a good structure for groups who are passing along a task and in which each member is expected to progressively build on the others’ work. A group of scholars coauthoring a research paper may work in such a manner, with each person adding to the paper and then passing it on to the next person in the circle. In this case, they can ask the previous person questions and write with the next person’s area of expertise in mind. The “Wheel” group structure in Figure 1 shows an alternative organization pattern. In this structure, Tara is very reachable by all members of the group. This can be a useful structure when Tara is the person with the most expertise in the task or the leader who needs to review and approve work at each step before it is passed along to other group members. But Phillip and Shadow, for example, wouldn’t likely work together without Tara being involved.

Looking at the group structures, we can make some assumptions about the communication that takes place in them. The wheel is an example of a centralized structure, while the circle is decentralized. Research has shown that centralized groups are better than decentralized groups in terms of speed and efficiency (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). But decentralized groups are more effective at solving complex problems. In centralized groups like the wheel, the person with the most connections, person C, is also more likely to be the leader of the group or at least have more status among group members, largely because that person has a broad perspective of what’s going on in the group. The most central person can also act as a gatekeeper. Since this person has access to the most information, which is usually a sign of leadership or status, he or she could consciously decide to limit the flow of information. But in complex tasks, that person could become overwhelmed by the burden of processing and sharing information with all the other group members. The circle structure is more likely to emerge in groups where collaboration is the goal and a specific task and course of action isn’t required under time constraints. While the person who initiated the group or has the most expertise in regards to the task may emerge as a leader in a decentralized group, the equal access to information lessens the hierarchy and potential for gatekeeping that is present in the more centralized groups.

Interdependence

Small groups exhibit interdependence, meaning they share a common purpose and a common fate. If the actions of one or two group members lead to a group deviating from or not achieving their purpose, then all members of the group are affected. Conversely, if the actions of only a few of the group members lead to success, then all members of the group benefit. This is a major contributor to many college students’ dislike of group assignments, because they feel a loss of control and independence that they have when they complete an assignment alone. This concern is valid in that their grades might suffer because of the negative actions of someone else or their hard work may go to benefit the group member who just skated by. Group meeting attendance is a clear example of the interdependent nature of group interaction. Many of us have arrived at a group meeting only to find half of the members present. In some cases, the group members who show up have to leave and reschedule because they can’t accomplish their task without the other members present. Group members who attend meetings but withdraw or don’t participate can also derail group progress. Although it can be frustrating to have your job, grade, or reputation partially dependent on the actions of others, the interdependent nature of groups can also lead to higher-quality performance and output, especially when group members are accountable for their actions.

Shared Identity

The shared identity of a group manifests in several ways. Groups may have official charters or mission and vision statements that lay out the identity of a group. For example, the Girl Scout mission states that “Girl Scouting builds girls of courage, confidence, and character, who make the world a better place” (Girl Scouts, 2012). The mission for this large organization influences the identities of the thousands of small groups called troops. Group identity is often formed around a shared goal and/or previous accomplishments, which adds dynamism to the group as it looks toward the future and back on the past to inform its present. Shared identity can also be exhibited through group names, slogans, songs, handshakes, clothing, or other symbols. At a family reunion, for example, matching t-shirts specially made for the occasion, dishes made from recipes passed down from generation to generation, and shared stories of family members that have passed away help establish a shared identity and social reality.

A key element of the formation of a shared identity within a group is the establishment of the in-group as opposed to the out-group. The degree to which members share in the in-group identity varies from person to person and group to group. Even within a family, some members may not attend a reunion or get as excited about the matching t-shirts as others. Shared identity also emerges as groups become cohesive, meaning they identify with and like the group’s task and other group members. The presence of cohesion and a shared identity leads to a building of trust, which can also positively influence productivity and members’ satisfaction.

Types of Small Groups

There are many types of small groups, but the most common distinction made between types of small groups is that of task-oriented and relational-oriented groups (Hargie, 2011). Task-oriented groups are formed to solve a problem, promote a cause, or generate ideas or information (McKay, Davis, & Fanning, 1995). In such groups, like a committee or study group, interactions and decisions are primarily evaluated based on the quality of the final product or output. The three main types of tasks are production, discussion, and problem-solving tasks (Ellis & Fisher, 1994). Groups faced with production tasks are asked to produce something tangible from their group interactions such as a report, design for a playground, musical performance, or fundraiser event. Groups faced with discussion tasks are asked to talk through something without trying to come up with a right or wrong answer. Examples of this type of group include a support group for people with HIV/AIDS, a book club, or a group for new fathers. Groups faced with problem-solving tasks have to devise a course of action to meet a specific need. These groups also usually include a production and discussion component, but the end goal isn’t necessarily a tangible product or a shared social reality through discussion. Instead, the end goal is a well-thought-out idea. Task-oriented groups require honed problem-solving skills to accomplish goals, and the structure of these groups is more rigid than that of relational-oriented groups.

Relational-oriented groups are formed to promote interpersonal connections and are more focused on quality interactions that contribute to the well-being of group members. Decision making is directed at strengthening or repairing relationships rather than completing discrete tasks or debating specific ideas or courses of action. All groups include task and relational elements, so it’s best to think of these orientations as two ends of a continuum rather than as mutually exclusive. For example, although a family unit works together daily to accomplish tasks like getting the kids ready for school and friendship groups may plan a surprise party for one of the members, their primary and most meaningful interactions are still relational. Since other chapters in this book focus specifically on interpersonal relationships, this chapter focuses more on task-oriented groups and the dynamics that operate within these groups.

To more specifically look at the types of small groups that exist, we can examine why groups form. Some groups are formed based on interpersonal relationships. Our family and friends are considered primary groups, or long-lasting groups that are formed based on relationships and include significant others. These are the small groups in which we interact most frequently. They form the basis of our society and our individual social realities. Kinship networks provide important support early in life and meet physiological and safety needs, which are essential for survival. They also meet higher-order needs such as social and self-esteem needs. When people do not interact with their biological family, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, they can establish fictive kinship networks, which are composed of people who are not biologically related but fulfill family roles and help provide the same support.

We also interact in many secondary groups, which are characterized by less frequent face-to-face interactions, less emotional and relational communication, and more task-related communication than primary groups (Barker, 1991). While we are more likely to participate in secondary groups based on self-interest, our primary-group interactions are often more reciprocal or other oriented. For example, we may join groups because of a shared interest or need.

Groups formed based on shared interest include social groups and leisure groups such as a group of independent film buffs, science fiction fans, or bird watchers. Some groups form to meet the needs of individuals or of a particular group of people. Examples of groups that meet the needs of individuals include study groups or support groups like a weight loss group. These groups are focused on individual needs, even though they meet as a group, and they are also often discussion oriented. Service groups, on the other hand, work to meet the needs of individuals but are task oriented. Service groups include Habitat for Humanity and Rotary Club chapters, among others. Still, other groups form around a shared need, and their primary task is advocacy. For example, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis is a group that was formed by a small group of eight people in the early 1980s to advocate for resources and support for the still relatively unknown disease that would later be known as AIDS. Similar groups form to advocate for everything from a stop sign at a neighborhood intersection to the end of human trafficking.

As we already learned, other groups are formed primarily to accomplish a task. Teams are task-oriented groups in which members are especially loyal and dedicated to the task and other group members (Larson & LaFasto, 1989). In professional and civic contexts, the word team has become popularized as a means of drawing on the positive connotations of the term—connotations such as “high-spirited,” “cooperative,” and “hardworking.” Scholars who have spent years studying highly effective teams have identified several common factors related to their success. Successful teams have (Adler & Elmhorst, 2005)

- clear and inspiring shared goals,

- a results-driven structure,

- competent team members,

- a collaborative climate,

- high standards for performance,

- external support and recognition, and

- ethical and accountable leadership.

Increasingly, small groups and teams are engaging in more virtual interaction. Virtual teams take advantage of new technologies and meet exclusively or primarily online to achieve their purpose or goal. Some virtual groups may complete their task without ever being physically face-to-face. Virtual groups bring with them distinct advantages and disadvantages that you can read more about in the “Getting Plugged In” feature next.

Getting Plugged In

Virtual groups and teams are now common in academic, professional, and personal contexts, as classes meet entirely online, work teams interface using webinar or video-conferencing programs, and people connect around shared interests in a variety of online settings. Virtual groups are popular in professional contexts because they can bring together people who are geographically dispersed (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). Virtual groups also increase the possibility for the inclusion of diverse members. The ability to transcend distance means that people with diverse backgrounds and diverse perspectives are more easily accessed than in many offline groups.

One disadvantage of virtual groups stems from the difficulties that technological mediation presents for the relational and social dimensions of group interactions (Walther & Bunz, 2005). An important part of coming together as a group is the socialization of group members into the desired norms of the group. Since norms are implicit, much of this information is learned through observation or conveyed informally from one group member to another. In fact, in traditional groups, group members passively acquire 50 percent or more of their knowledge about group norms and procedures, meaning they observe rather than directly ask (Comer, 1991). Virtual groups experience more difficulty with this part of socialization than copresent traditional groups do, since any form of electronic mediation takes away some of the richness present in face-to-face interaction.

To help overcome these challenges, members of virtual groups should be prepared to put more time and effort into building the relational dimensions of their group. Members of virtual groups need to make the social cues that guide new members’ socialization more explicit than they would in an offline group (Ahuja & Galvin, 2003). Group members should also contribute often, even if just supporting someone else’s contribution, because increased participation has been shown to increase liking among members of virtual groups (Walther & Bunz, 2005). Virtual group members should also make an effort to put relational content that might otherwise be conveyed through nonverbal or contextual means into the verbal part of a message, as members who include little social content in their messages or only communicate about the group’s task are more negatively evaluated. Virtual groups who do not overcome these challenges will likely struggle to meet deadlines, interact less frequently, and experience more absenteeism. What follows are some guidelines to help optimize virtual groups (Walter & Bunz, 2005):

- Get started interacting as a group as early as possible, since it takes longer to build social cohesion.

- Interact frequently to stay on task and avoid having work build up.

- Start working toward completing the task while initial communication about setup, organization, and procedures are taking place.

- Respond overtly to other people’s messages and contributions.

- Be explicit about your reactions and thoughts since typical nonverbal expressions may not be received as easily in virtual groups as they would be in colocated groups.

- Set deadlines and stick to them.

Discussion Questions:

- Make a list of some virtual groups to which you currently belong or have belonged to in the past. What are some differences between your experiences in virtual groups versus traditional colocated groups?

- What are some group tasks or purposes that you think lend themselves to being accomplished in a virtual setting? What are some group tasks or purposes that you think would be best handled in a traditional colocated setting? Explain your answers for each.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Small Groups

As with anything, small groups have their advantages and disadvantages. Advantages of small groups include shared decision making, shared resources, synergy, and exposure to diversity. It is within small groups that most of the decisions that guide our country, introduce local laws, and influence our family interactions are made. In a democratic society, participation in decision making is a key part of citizenship. Groups also help in making decisions involving judgment calls that have ethical implications or the potential to negatively affect people. Individuals making such high-stakes decisions in a vacuum could have negative consequences given the lack of feedback, input, questioning, and proposals for alternatives that would come from group interaction. Group members also help expand our social networks, which provide access to more resources. A local community-theater group may be able to put on a production with a limited budget by drawing on these connections to get set-building supplies, props, costumes, actors, and publicity in ways that an individual could not. The increased knowledge, diverse perspectives, and access to resources that groups possess relates to another advantage of small groups—synergy.

Synergy refers to the potential for gains in performance or heightened quality of interactions when complementary members or member characteristics are added to existing ones (Larson Jr., 2010). Because of synergy, the final group product can be better than what any individual could have produced alone. When I worked in housing and residence life, I helped coordinate a “World Cup Soccer Tournament” for the international students that lived in my residence hall. As a group, we created teams representing different countries around the world, made brackets for people to track progress and predict winners, got sponsors, gathered prizes, and ended up with a very successful event that would not have been possible without the synergy created by our collective group membership. The members of this group were also exposed to international diversity that enriched our experiences, which is also an advantage of group communication.

Participating in groups can also increase our exposure to diversity and broaden our perspectives. Although groups vary in the diversity of their members, we can strategically choose groups that expand our diversity, or we can unintentionally end up in a diverse group. When we participate in small groups, we expand our social networks, which increase the possibility to interact with people who have different cultural identities than ourselves. Since group members work together toward a common goal, shared identification with the task or group can give people with diverse backgrounds a sense of commonality that they might not have otherwise. Even when group members share cultural identities, the diversity of experience and opinion within a group can lead to broadened perspectives as alternative ideas are presented and opinions are challenged and defended. One of my favorite parts of facilitating class discussion is when students with different identities and/or perspectives teach one another things in ways that I could not on my own. This example brings together the potential of synergy and diversity. People who are more introverted or just avoid group communication and voluntarily distance themselves from groups—or are rejected from groups—risk losing opportunities to learn more about others and themselves.

There are also disadvantages to small group interaction. In some cases, one person can be just as or more effective than a group of people. Think about a situation in which a highly specialized skill or knowledge is needed to get something done. In this situation, one very knowledgeable person is probably a better fit for the task than a group of less knowledgeable people. Group interaction also has a tendency to slow down the decision-making process. Individuals connected through a hierarchy or chain of command often work better in situations where decisions must be made under time constraints. When group interaction does occur under time constraints, having one “point person” or leader who coordinates action and gives final approval or disapproval on ideas or suggestions for actions is best.

Group communication also presents interpersonal challenges. A common problem is coordinating and planning group meetings due to busy and conflicting schedules. Some people also have difficulty with the other-centeredness and self-sacrifice that some groups require. The interdependence of group members that we discussed earlier can also create some disadvantages. Group members may take advantage of the anonymity of a group and engage in social loafing, meaning they contribute less to the group than other members or than they would if working alone (Karau & Williams, 1993). Social loafers expect that no one will notice their behaviors or that others will pick up their slack. It is this potential for social loafing that makes many students and professionals dread group work, especially those who have a tendency to cover for other group members to prevent the social loafer from diminishing the group’s productivity or output.

THE BONA FIDE GROUP PERSPECTIVE

up to this point we have discussed small group communication in general, but this book is guided by a particular theory. you'll find sections in each chapter pointing to how the theory, Bona Fide Group Perspective, changes the way we look at every aspects of groups; Putnam and Stohl (1990) responded to increasing use of "natural" groups for research; before had been primarily experimental; used laboratory groups where five or so people brought together for a limited amount of time, generally no more than two hours, to complete a specific task; they had no history and no expectation of future interaction; however, we know that these change the ways in which we interact with each other; Putnam & Stohl argued that if we were going to study "natural" groups then we needed a better theoretical framework that took into account all of their characteristics; can also be used to study laboratory groups; The Bona Fide Group Perspective has three key elements: stable yet permeable boundaries, interdependence with context, and unstable & ambiguous borders. A boundary establishes who is a group member and who is not a group member. This is tied to an individual's ability to identify as a group member. The boundaries are stable (i.e. being able to identify who is and who is not a group member remains stable across time), yet permeable. The notion of permeability reflects the fluid and dynamic nature of group membership. Context refers to the group's physical

Improving Your Group Experiences

If you experience feelings of fear and dread when an instructor says you will need to work in a group, you may experience what is called grouphate (Meyers & Goodboy, 2005). Like many of you, I also had some negative group experiences in college that made me think similarly to a student who posted the following on a teaching blog: “Group work is code for ‘work as a group for a grade less than what you can get if you work alone’” (Weimer, 2008).

But then I took a course called “Small Group and Team Communication” with an amazing teacher who later became one of my most influential mentors. She emphasized the fact that we all needed to increase our knowledge about group communication and group dynamics in order to better our group communication experiences—and she was right. So the first piece of advice to help you start improving your group experiences is to closely study the group communication chapters in this textbook and to apply what you learn to your group interactions. Neither students nor faculty are born knowing how to function as a group, yet students and faculty often think we’re supposed to learn as we go, which increases the likelihood of a negative experience.

A second piece of advice is to meet often with your group (Myers & Goodboy, 2005). Of course, to do this you have to overcome some scheduling and coordination difficulties, but putting other things aside to work as a group helps set up a norm that group work is important and worthwhile. Regular meetings also allow members to interact with each other, which can increase social bonds, build a sense of interdependence that can help diminish social loafing, and establish other important rules and norms that will guide future group interaction. Instead of committing to frequent meetings, many student groups use their first meeting to equally divide up the group’s tasks so they can then go off and work alone (not as a group). While some group work can definitely be done independently, dividing up the work and assigning someone to put it all together doesn’t allow group members to take advantage of one of the most powerful advantages of group work—synergy.