6 Understanding Group Formation

Learning Objectives

- Explain the reasons why people join groups

- Describe how groups impact task performance

- Identify what makes groups most effective

- Discuss the utility of descriptive models of group development

- Explain how the Bona Fide Group Perspective changes the models of group development

This chapter assumes that a thorough understanding of people requires a thorough understanding of groups. Each of us is an autonomous individual seeking our own objectives, yet we are also members of groups—groups that constrain us, guide us, and sustain us. Just as each of us influences the group and the people in the group, so, too, do groups change each one of us. Joining groups satisfies our need to gain information, to belong and be understood, define our sense of self and social identity, and achieve goals that might elude us if we worked alone. Groups are also practically significant, for much of the world’s work is done by groups rather than by individuals. Success sometimes eludes our groups, but when group members learn to work together as a cohesive team their success becomes more certain.

Psychologists study groups because nearly all human activities—working, learning, worshiping, relaxing, and playing—occur in groups. The lone individual who is cut off from all groups is a rarity. Most of us live out our lives in groups, and these groups have a profound impact on our thoughts, feelings, and actions. Many psychologists focus their attention on single individuals, but social psychologists and communication scholars expand their analysis to include groups, organizations, communities, and even cultures.

This chapter examines the psychology of groups and group membership. It begins with a basic question: What is the psychological significance of groups? This chapter then reviews some of the key findings from studies of groups. Researchers have asked many questions about people and groups: Do people work as hard as they can when they are in groups? Are groups more cautious than individuals? Do groups make wiser decisions than single individuals? In many cases, the answers are not what common sense and folk wisdom might suggest.

The Psychological Significance of Groups

Many people loudly proclaim their autonomy and independence. Like Ralph Waldo Emerson (1903/2004), they avow, “I must be myself. I will not hide my tastes or aversions . . . . I will seek my own” (p. 127). Even though people are capable of living separately and apart from others, they join with others because groups meet their psychological and social needs.

The Need to Belong

Across individuals, societies, and even eras, humans consistently seek inclusion over exclusion, membership over isolation, and acceptance over rejection. As Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary (1995) conclude, humans have a need to belong: “a pervasive drive to form and maintain at least a minimum quantity of lasting, positive, and impactful interpersonal relationships” (p. 497). And most of us satisfy this need by joining groups. When surveyed, 87.3% of Americans reported that they lived with other people, including family members, partners, and roommates (Davis & Smith, 2007). The majority, ranging from 50% to 80%, reported regularly doing things in groups, such as attending a sports event together, visiting one another for the evening, sharing a meal together, or going out as a group to see a movie (Putnam, 2000).

People respond negatively when their need to belong is unfulfilled. People who are accepted members of a group tend to feel happier and more satisfied. But should they be rejected by a group, they feel unhappy, helpless, and depressed. Studies of ostracism—the deliberate exclusion from groups—indicate this experience is highly stressful and can lead to depression, confused thinking, and even aggression (Williams, 2007). When researchers used a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner to track neural responses to exclusion, they found that people who were left out of a group activity displayed heightened cortical activity in two specific areas of the brain—the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula. These areas of the brain are associated with the experience of physical pain sensations (Eisenberger et al., 2003). It hurts, quite literally, to be left out of a group.

Affiliation in Groups

Groups not only satisfy the need to belong, but they also provide members with information, assistance, and social support. Leon Festinger’s theory of social comparison (1950, 1954) suggested that in many cases people join with others to evaluate the accuracy of their personal beliefs and attitudes. Stanley Schachter (1959) explored this process by putting individuals in ambiguous, stressful situations and asking them if they wished to wait alone or with others. He found that people affiliate in such situations—they seek the company of others.

Although any kind of companionship is appreciated, we prefer those who provide us with reassurance and support as well as accurate information. In some cases, we also prefer to join with others who are even worse off than we are. Imagine, for example, how you would respond when the teacher hands back the test and yours is marked 85%. Do you want to affiliate with a friend who got a 95% or a friend who got a 78%? To maintain a sense of self-worth, people seek out and compare themselves to the less fortunate. This process is known as downward social comparison.

Identity and Membership

Groups are not only founts of information during times of ambiguity, they also help us answer the existentially significant question, “Who am I?” People are defined not only by their traits, preferences, interests, likes, and dislikes, but also by their friendships, social roles, family connections, and group memberships. The self is not just a “me,” but also a “we.”

Even demographic qualities such as sex or age can influence us if we categorize ourselves based on these qualities. Social identity theory, for example, assumes that we don’t just classify other people into such social categories as man, woman, White, Black, Latinx, elderly, or college student, we also categorize ourselves. According to Tajfel and Turner (1986), social identities are directed by our memberships in particular groups. or social categories. If we strongly identify with these categories, then we will ascribe the characteristics of the typical member of these groups to ourselves, and so stereotype ourselves. If, for example, we believe that college students are intellectual, then we will assume we, too, are intellectual if we identify with that group (Hogg, 2001).

Groups also provide a variety of means for maintaining and enhancing a sense of self-worth, as our assessment of the quality of groups we belong to influences our collective self-esteem (Crocker & Luhtanen, 1990). If our self-esteem is shaken by a personal setback, we can focus on our group’s success and prestige. In addition, by comparing our group to other groups, we frequently discover that we are members of the better group, and so can take pride in our superiority. By denigrating other groups, we elevate both our personal and our collective self-esteem (Crocker & Major, 1989).

Mark Leary’s (2007) sociometer model goes so far as to suggest that “self-esteem is part of a sociometer that monitors peoples’ relational value in other people’s eyes” (p. 328). He maintains self-esteem is not just an index of one’s sense of personal value, but also an indicator of acceptance into groups. Like a gauge that indicates how much fuel is left in the tank, a dip in self-esteem indicates exclusion from our group is likely. Disquieting feelings of self-worth, then, prompt us to search for and correct characteristics and qualities that put us at risk of social exclusion. Self-esteem is not just high self-regard, but the self-approbation that we feel when included in groups (Leary & Baumeister, 2000).

Evolutionary Advantages of Group Living

Groups may be humans’ most useful invention, for they provide us with the means to reach goals that would elude us if we remained alone. Individuals in groups can secure advantages and avoid disadvantages that would plague the lone individuals. In his theory of social integration, Moreland (1987) concludes that groups tend to form whenever “people become dependent on one another for the satisfaction of their needs” (p. 104). The advantages of group life may be so great that humans are biologically prepared to seek membership and avoid isolation. From an evolutionary psychology perspective, because groups have increased humans’ overall fitness for countless generations, individuals who carried genes that promoted solitude-seeking were less likely to survive and procreate compared to those with genes that prompted them to join groups (Darwin, 1859/1963). This process of natural selection culminated in the creation of a modern human who seeks out membership in groups instinctively, for most of us are descendants of “joiners” rather than “loners.”

Motivation and Performance

Social Facilitation in Groups

Do people perform more effectively when alone or when part of a group? Norman Triplett (1898) examined this issue in one of the first empirical studies in psychology. While watching bicycle races, Triplett noticed that cyclists were faster when they competed against other racers than when they raced alone against the clock. To determine if the presence of others leads to the psychological stimulation that enhances performance, he arranged for 40 children to play a game that involved turning a small reel as quickly as possible (see Figure 1). When he measured how quickly they turned the reel, he confirmed that children performed slightly better when they played the game in pairs compared to when they played alone (see Stroebe, 2012; Strube, 2005).

Triplett succeeded in sparking interest in a phenomenon now known as social facilitation: the enhancement of an individual’s performance when that person works in the presence of other people. However, it remained for Robert Zajonc (1965) to specify when social facilitation does and does not occur. After reviewing prior research, Zajonc noted that the facilitating effects of an audience usually only occur when the task requires the person to perform dominant responses (i.e., ones that are well-learned or based on instinctive behaviors). If the task requires nondominant responses (i.e., novel, complicated, or untried behaviors that the organism has never performed before or has performed only infrequently) then the presence of others inhibits performance. Hence, students write poorer quality essays on complex philosophical questions when they labor in a group rather than alone (Allport, 1924), but they make fewer mistakes in solving simple, low-level multiplication problems with an audience or a co-actor than when they work in isolation (Dashiell, 1930).

Social facilitation, then, depends on the task: other people facilitate performance when the task is so simple that it requires only dominant responses, but others interfere when the task requires nondominant responses. However, a number of psychological processes combine to influence when social facilitation, not social interference, occurs. Studies of the challenge-threat response and brain imaging, for example, confirm that we respond physiologically and neurologically to the presence of others (Blascovich et al., 1999). Other people also can trigger evaluation apprehension, particularly when we feel that our individual performance will be known to others, and those others might judge it negatively (Bond et al., 1996). The presence of other people can also cause perturbations in our capacity to concentrate on and process information (Harkins, 2006). Distractions due to the presence of other people have been shown to improve performance on certain tasks, such as the Stroop task, but undermine performance on more cognitively demanding tasks (Huguet et al., 1999).

Social Loafing

Groups usually outperform individuals. A single student, working alone on a paper, will get less done in an hour than will four students working on a group project. One person playing a tug-of-war game against a group will lose. A crew of movers can pack up and transport your household belongings faster than you can by yourself. As the saying goes, “Many hands make light the work” (Littlepage, 1991; Steiner, 1972).

Groups, though, tend to be underachievers. Studies of social facilitation confirmed the positive motivational benefits of working with other people on well-practiced tasks in which each member’s contribution to the collective enterprise can be identified and evaluated. But what happens when tasks require a truly collective effort? First, when people work together they must coordinate their individual activities and contributions to reach the maximum level of efficiency—but they rarely do (Diehl & Stroebe, 1987). Three people in a tug-of-war competition, for example, invariably pull and pause at slightly different times, so their efforts are uncoordinated. The result is coordination loss: the three-person group is stronger than a single person, but not three times as strong. Second, people just don’t exert as much effort when working on a collective endeavor, nor do they expend as much cognitive effort trying to solve problems, as they do when working alone. They display social loafing (Latané, 1981).

Bibb Latané, Kip Williams, and Stephen Harkins (1979) examined both coordination losses and social loafing by arranging for students to cheer or clap either alone or in groups of varying sizes. The students cheered alone or in 2- or 6-person groups, or they were lead to believe they were in 2- or 6-person groups (those in the “pseudo-groups” wore blindfolds and headsets that played masking sound). Groups generated more noise than solitary subjects, but the productivity dropped as the groups became larger in size. In dyads, each subject worked at only 66% of capacity, and in 6-person groups at 36%. Productivity also dropped when subjects merely believed they were in groups. If subjects thought that one other person was shouting with them, they shouted 82% as intensely, and if they thought five other people were shouting, they reached only 74% of their capacity. These losses in productivity were not due to coordination problems; this decline in production could be attributed only to a reduction in effort—to social loafing (Latané et al., 1979, Experiment 2).

Teamwork

Social loafing is not a rare phenomenon. When sales personnel work in groups with shared goals, they tend to “take it easy” if another salesperson is nearby who can do their work (George, 1992). People who are trying to generate new, creative ideas in group brainstorming sessions usually put in less effort and are thus less productive than people who are generating new ideas individually (Paulus & Brown, 2007). Students assigned group projects often complain of inequity in the quality and quantity of each member’s contributions: Some people just don’t work as much as they should to help the group reach its learning goals (Neu, 2012). People carrying out all sorts of physical and mental tasks expend less effort when working in groups, and the larger the group, the more they loaf (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Groups can, however, overcome this impediment to performance through teamwork. A group may include many talented individuals, but they must learn how to pool their individual abilities and energies to maximize the team’s performance. Team goals must be set, work patterns structured, and a sense of group identity developed. Individual members must learn how to coordinate their actions, and any strains and stresses in interpersonal relations need to be identified and resolved (Salas et al., 2009).

Researchers have identified two key ingredients to effective teamwork: a shared mental representation of the task and group cohesion. Teams improve their performance over time as they develop a shared understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting. Some semblance of this shared mental model, is present nearly from its inception, but as the team practices, differences among the members in terms of their understanding of their situation and their team diminish as a consensus becomes implicitly accepted (Tindale et al., 2008). Effective teams are also, in most cases, cohesive groups (Dion, 2000). Group cohesion is the integrity, solidarity, social integration, or unity of a group. In most cases, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals. Members tend to enjoy their groups more when they are cohesive, and cohesive groups usually outperform ones that lack cohesion. This cohesion-performance relationship, however, is a complex one. Meta-analytic studies suggest that cohesion improves teamwork among members, but that performance quality influences cohesion more than cohesion influences performance (Mullen & Copper, 1994; Mullen et al., 1998). Cohesive groups also can be spectacularly unproductive if the group’s norms stress low productivity rather than high productivity (Seashore, 1954). Group cohesion will be discussed in more detail in a later chapter.

GROUP DEVELOPMENT

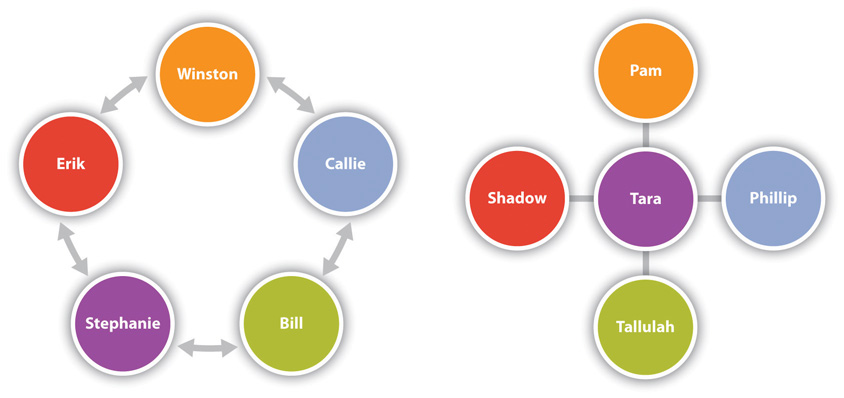

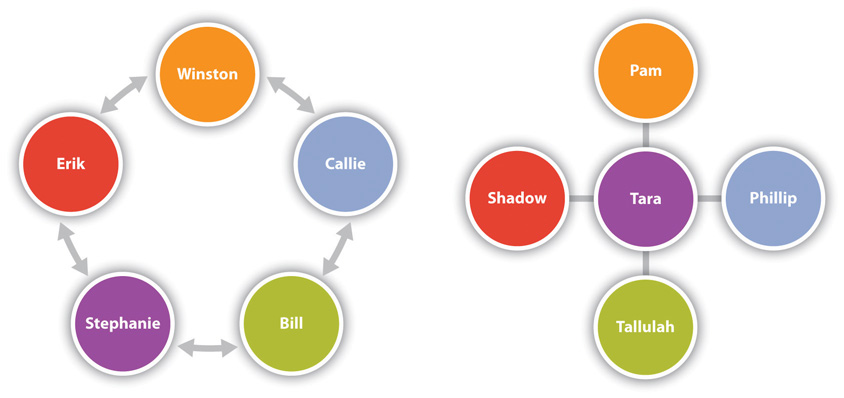

From the time they are formed, groups evolve and can go through a variety of changes over the course of their life cycles. Researchers have sought to identify common patterns in group development. These are referred to as descriptive models (Beebe & Masterson, 2015). Descriptive models can help us make sense of our group experiences by describing what might be ‘normal’ or ‘typical’ group processes. In the following sections, we will discuss two examples of descriptive models of group development — Tuckman’s model and punctuated equilibrium.

TUCKMAN MODEL OF Group Development

American organizational psychologist Bruce Tuckman presented a robust model in 1965 that is still widely used today. Based on his observations of group behavior in a variety of settings, he proposed a four-stage map of group evolution, also known as Tuckman's model of group development (Tuckman, 1965). Later he enhanced the model by adding a fifth and final stage, the adjourning phase. Interestingly enough, just as an individual moves through developmental stages such as childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, so does a group, although in a much shorter period of time. According to this theory, in order to successfully facilitate a group, the leader needs to move through various leadership styles over time. Generally, this is accomplished by first being more directive, eventually serving as a coach, and later, once the group is able to assume more power and responsibility for itself, shifting to a delegator. While research has not confirmed that this is descriptive of how groups progress, knowing and following these steps can help groups be more effective. For example, groups that do not go through the storming phase early on will often return to this stage toward the end of the group process to address unresolved issues. Another example of the validity of the group development model involves groups that take the time to get to know each other socially in the forming stage. When this occurs, groups tend to handle future challenges better because the individuals have an understanding of each other’s needs.

Forming

In the forming stage, the group comes together for the first time. The members may already know each other or they may be total strangers. In either case, there is a level of formality, some anxiety, and a degree of guardedness as group members are not sure what is going to happen next. “Will I be accepted? What will my role be? Who has the power here?” These are some of the questions participants think about during this stage of group formation. Because of the large amount of uncertainty, members tend to be polite, conflict avoidant, and observant. They are trying to figure out the “rules of the game” without being too vulnerable. At this point, they may also be quite excited and optimistic about the task at hand, perhaps experiencing a level of pride at being chosen to join a particular group. Group members are trying to achieve several goals at this stage, although this may not necessarily be done consciously. First, they are trying to get to know each other. Often this can be accomplished by finding some common ground. Members also begin to explore group boundaries to determine what will be considered acceptable behavior. “Can I interrupt? Can I leave when I feel like it?” This trial phase may also involve testing the appointed leader or seeing if a leader emerges from the group. At this point, group members are also discovering how the group will work in terms of what needs to be done and who will be responsible for each task. This stage is often characterized by abstract discussions about issues to be addressed by the group; those who like to get moving can become impatient with this part of the process. This phase is usually short in duration, perhaps a meeting or two.

Storming

Once group members feel sufficiently safe and included, they tend to enter the storming phase. Participants focus less on keeping their guard up as they shed social facades, becoming more authentic and more argumentative. Group members begin to explore their power and influence, and they often stake out their territory by differentiating themselves from the other group members rather than seeking common ground. Discussions can become heated as participants raise contending points of view and values, or argue over how tasks should be done and who is assigned to them. It is not unusual for group members to become defensive, competitive, or jealous. They may even take sides or begin to form cliques within the group. Questioning and resisting direction from the leader is also quite common. “Why should I have to do this? Who designed this project in the first place? Why do I have to listen to you?” Although little seems to get accomplished at this stage, group members are becoming more authentic as they express their deeper thoughts and feelings. What they are really exploring is “Can I truly be me, have power, and be accepted?” During this chaotic stage, a great deal of creative energy that was previously buried is released and available for use, but it takes skill to move the group from storming to norming. In many cases, the group gets stuck in the storming phase.

Avoid Getting Stuck in the Storming Phase

There are several steps you can take to avoid getting stuck in the storming phase of group development. Try the following if you feel the group process you are involved in is not progressing:

- Normalize conflict. Let members know this is a natural phase in the group-formation process.

- Be inclusive. Continue to make all members feel included and invite all views into the room. Mention how diverse ideas and opinions help foster creativity and innovation.

- Make sure everyone is heard. Facilitate heated discussions and help participants understand each other.

- Support all group members. This is especially important for those who feel more insecure.

- Remain positive. This is a key point to remember about the group’s ability to accomplish its goal.

- Don’t rush the group’s development. Remember that working through the storming stage can take several meetings.

Once group members discover that they can be authentic and that the group is capable of handling differences without dissolving, they are ready to enter the next stage, norming.

Norming

“We survived!” is the common sentiment at the norming stage. Group members often feel elated at this point, and they are much more committed to each other and the group’s goal. Feeling energized by knowing they can handle the “tough stuff,” group members are now ready to get to work. Finding themselves more cohesive and cooperative, participants find it easy to establish their own ground rules (or norms) and define their operating procedures and goals. The group tends to make big decisions, while subgroups or individuals handle the smaller decisions. Hopefully, at this point, the group is more open and respectful toward each other, and members ask each other for both help and feedback. They may even begin to form friendships and share more personal information with each other. At this point, the leader should become more of a facilitator by stepping back and letting the group assume more responsibility for its goal. Since the group’s energy is running high, this is an ideal time to host a social or team-building event.

Performing

Galvanized by a sense of shared vision and a feeling of unity, the group is ready to go into high gear. Members are more interdependent, individuality and differences are respected, and group members feel themselves to be part of a greater entity. At the performing stage, participants are not only getting the work done, but they also pay greater attention to how they are doing it. They ask questions like, “Do our operating procedures best support productivity and quality assurance? Do we have suitable means for addressing differences that arise so we can preempt destructive conflicts? Are we relating to and communicating with each other in ways that enhance group dynamics and help us achieve our goals? How can I further develop as a person to become more effective?” By now, the group has matured, becoming more competent, autonomous, and insightful. Group leaders can finally move into coaching roles and help members grow in skill and leadership.

Adjourning

Just as groups form, so do they end. For example, many groups or teams formed in a business context are project-oriented and therefore are temporary in nature. Alternatively, a working group may dissolve due to organizational restructuring. Just as when we graduate from school or leave home for the first time, these endings can be bittersweet, with group members feeling a combination of victory, grief, and insecurity about what is coming next. For those who like routine and bond closely with fellow group members, this transition can be particularly challenging. Group leaders and members alike should be sensitive to handling these endings respectfully and compassionately. An ideal way to close a group is to set aside time to debrief (“How did it all go? What did we learn?”), acknowledge each other, and celebrate a job well done.

The Punctuated-Equilibrium Model

As you may have noted, the five-stage model we have just reviewed is a linear process. According to the model, a group progresses to the performing stage, at which point it finds itself in an ongoing, smooth-sailing situation until the group dissolves. In reality, subsequent researchers, most notably Joy H. Karriker, have found that the life of a group is much more dynamic and cyclical in nature (Karriker, 2005). For example, a group may operate in the performing stage for several months. Then, because of a disruption, such as a competing emerging technology that changes the rules of the game or the introduction of a new CEO, the group may move back into the storming phase before returning to performing. Ideally, any regression in the linear group progression will ultimately result in a higher level of functioning. Proponents of this cyclical model draw from behavioral scientist Connie Gersick’s study of punctuated equilibrium (Gersick, 1991).

The concept of punctuated equilibrium was first proposed in 1972 by paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould, who both believed that evolution occurred in rapid, radical spurts rather than gradually over time. Identifying numerous examples of this pattern in social behavior, Gersick found that the concept applied to organizational change. She proposed that groups remain fairly static, maintaining a certain equilibrium for long periods of time. Change during these periods is incremental, largely due to the resistance to change that arises when systems take root and processes become institutionalized. In this model, revolutionary change occurs in brief, punctuated bursts, generally catalyzed by a crisis or problem that breaks through the systemic inertia and shakes up the deep organizational structures in place. At this point, the organization or group has the opportunity to learn and create new structures that are better aligned with current realities. Whether the group does this is not guaranteed. In sum, in Gersick’s model, groups can repeatedly cycle through the storming and performing stages, with revolutionary change taking place during short transitional windows. For organizations and groups who understand that disruption, conflict, and chaos are inevitable in the life of a social system, these disruptions represent opportunities for innovation and creativity.

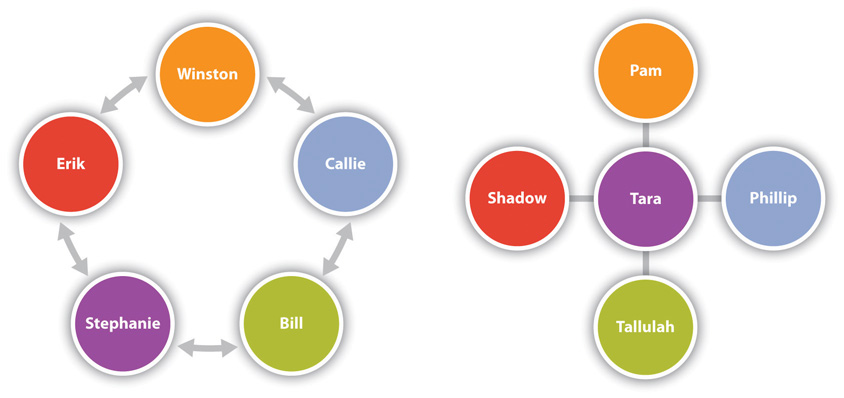

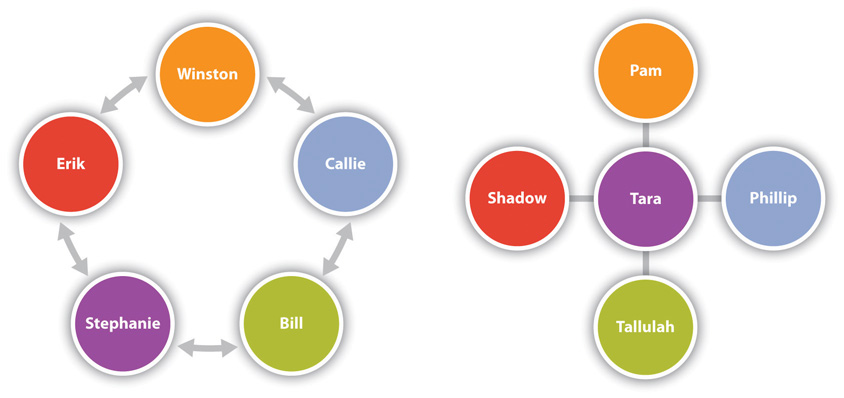

Many theories seek to understand group formation through the lens of a single group. The Bona Fide Group Perspective (BFGP), however, situates group formation in the relationships between and among the groups and organizations surrounding that.

A group’s boundaries, for example, determine both who is and who is not a group member as well as the ease with which group members move in and out of formal and informal group membership. The tension in this boundary—it’s stability and permeability—affects group cohesion, which requires both. If a group’s boundary lacks permeability the group becomes static, without the movement of members and resources in and out. A static group may have closeness forced on them but are less likely to develop cohesion—true solidarity and unity. On the other hand, if the group’s boundary lacks stability, cohesion is unlikely to develop because groups lack a defining edge to their group membership. With who is and who is not a group member unclear, group cohesion is difficult to develop. Stable yet permeable boundaries affect group formation in other ways, such as a group’s initial formation and their end. Again, as members move in and out of the group they are both (re)created as a group and experience an end. The end is not always the complete cessation of the group as some of the same members may participate in the formation of a new group.

Group formation occurs over time. One way this happens is through the creation of norms and the occasional abrupt changes to those norms. Norm creation is an important element of group development. The ways in which a group is interdependent with its context highlights how norms are frequently developed in response to norms outside of the group’s boundary. Groups either adopt, adapt, or reject these norms. This process highlights the interlocked behaviors and interwoven interpretive frames that are highlighted by the group’s interdependence with its context.

A group’s shifting coalitions with other groups and organizations, an element of unstable and ambiguous borders, shape group formation as well. These alliances affect the individual’s need for a group. With two allied groups individuals may better satisfy their needs. This impacts the formation of the group as well. Individuals may know each other from previous participation in an allied group. This facilitates group formation, allowing groups to move beyond the initial awkward stages of interaction quickly. In addition, group identity changes over time and group formation can be observed in these identity shifts.

All these differences add up to the possibility of studying group formation differently. Theorists and applied scholars must look outside the group to gain a complete understanding of group formation. The BFGP changes both where and how we look at group formation.

Review & Reflection Questions

- Why do people often join groups? What are some reasons you have joined groups in the past?

- Do people perform more effectively when alone or when part of a group? Under what conditions?

- If you were a college professor, what would you do to increase the success of in-class groups and teams?

- What do descriptive models do for us? How might they be useful to groups?

- Have you observed a group going through these phases in the past? What can you learn from those experiences?

References

- Allport, F. H. (1924). Social psychology. Houghton Mifflin.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

- Beebe, S.A., & Masterson, J.T. (2015). Communicating in small groups: Principles and practices (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Blascovich, J., Mendes, W. B., Hunter, S. B., & Salomon, K. (1999). Social “facilitation” as challenge and threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 68–77.

- Bond, C. F., Atoum, A. O., & VanLeeuwen, M. D. (1996). Social impairment of complex learning in the wake of public embarrassment. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18, 31–44.

- Crocker, J., & Luhtanen, R. (1990). Collective self-esteem and ingroup bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 60–67.

- Crocker, J., & Major, B. (1989). Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review, 96, 608–630.

- Darwin, C. (1859/1963). The origin of species. Washington Square Press.

- Dashiell, J. F. (1930). An experimental analysis of some group effects. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 25, 190–199.

- Davis, J. A., & Smith, T. W. (2007). General social surveys (1972–2006). [machine-readable data file]. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center & Storrs, CT: The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research. Retrieved from http://www.norc.uchicago.edu

- Diehl, M., & Stroebe, W. (1987). Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: Toward the solution of a riddle. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 497–509.

- Dion, K. L. (2000). Group cohesion: From “field of forces” to multidimensional construct. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4, 7–26.

- Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302, 290–292.

- Emerson, R. W. (2004). Essays and poems by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Barnes & Noble. (originally published 1903).

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140.

- Festinger, L. (1950). Informal social communication. Psychological Review, 57, 271–282.

- George, J. M. (1992). Extrinsic and intrinsic origins of perceived social loafing in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 191–202.

- Gersick, C. J. G. (1991). Revolutionary change theories: A multilevel exploration of the punctuated equilibrium paradigm. Academy of Management Review, 16, 10–36.

- Harkins, S. G. (2006). Mere effort as the mediator of the evaluation-performance relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(3), 436–455.

- Hogg, M. A. (2001). Social categorization, depersonalization, and group behavior. In M. A. Hogg & R. S. Tindale (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Group processes (pp. 56–85). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Huguet, P., Galvaing, M. P., Monteil, J. M., & Dumas, F. (1999). Social presence effects in the Stroop task: Further evidence for an attentional view of social facilitation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1011–1025.

- Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 681–706.

- Karriker, J. H. (2005). Cyclical group development and interaction-based leadership emergence in autonomous teams: An integrated model. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11, 54–64.

- Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36, 343–356.

- Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 822–832.

- Leary, M. R. (2007). Motivational and emotional aspects of the self. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 317–344.

- Leary, M. R. & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 32, 1–62.

- Littlepage, G. E. (1991). Effects of group size and task characteristics on group performance: A test of Steiner’s model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 449–456.

- Moreland, R. L. (1987). The formation of small groups. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 8, 80–110.

- Mullen, B., & Copper, C. (1994). The relation between group cohesiveness and performance: An integration. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 210–227.

- Mullen, B., Driskell, J. E., & Salas, E. (1998). Meta-analysis and the study of group dynamics. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2, 213–229.

- Neu, W. A. (2012). Unintended cognitive, affective, and behavioral consequences of group assignments. Journal of Marketing Education, 34(1), 67–81.

- Paulus, P. B., & Brown, V. R. (2007). Toward more creative and innovative group idea generation: A cognitive-social-motivational perspective of brainstorming. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 248–265.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

- Salas, E., Rosen, M. A., Burke, C. S., & Goodwin, G. F. (2009). The wisdom of collectives in organizations: An update of the teamwork competencies. In E. Salas, G. F. Goodwin, & C. S. Burke (Eds.), Team effectiveness in complex organizations: Cross-disciplinary perspectives and approaches (pp. 39–79). Routledge.

- Schachter, S. (1959). The psychology of affiliation. Stanford University Press.

- Seashore, S. E. (1954). Group cohesiveness in the industrial work group. Institute for Social Research.

- Steiner, I. D. (1972). Group process and productivity. Academic Press.

- Stroebe, W. (2012). The truth about Triplett (1898), but nobody seems to care. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(1), 54–57.

- Strube, M. J. (2005). What did Triplett really find? A contemporary analysis of the first experiment in social psychology. American Journal of Psychology, 118, 271–286.

- Tajfel, H. & Turner, J.C. (1986). The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In S. Worchel & L.W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations.(pp. 7-24). Nelson-Hall

- Tindale, R. S., Stawiski, S., & Jacobs, E. (2008). Shared cognition and group learning. In V. I. Sessa & M. London (Eds.), Work group learning: Understanding, improving and assessing how groups learn in organizations (pp. 73–90). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. American Journal of Psychology, 9, 507–533.

- Tuckman, B. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384–399.

- Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 425–452.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149, 269–274.

Authors & Attribution

The sections “The Psychological Significance of Groups” and “Motivation and Performance” are adapted and condensed from: Forsyth, D. R. (2019). The psychology of groups. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. DEF publishers. nobaproject.com. This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The section “Group Development” is adapted from “Group Dynamics” in Organizational Behaviour from the University of Minnesota. The book was adapted from a work produced and distributed under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA) by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution. This work is made available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

Learning Objectives

- Describe how diversity can enhance decision-making and problem-solving

- Identify challenges and best practices for working with multicultural teams

- Discuss divergent cultural characteristics and list several examples of such characteristics in the culture(s) you identify with

Decision-making and problem-solving can be much more dynamic and successful when performed in a diverse team environment. The multiple diverse perspectives can enhance both the understanding of the problem and the quality of the solution. Yet, working in diverse teams can be challenging given different identities, cultures, beliefs, and experiences. In this chapter, we will discuss the effects of team diversity on group decision-making and problem-solving, identify best practices and challenges for working in and with multicultural teams, and dig deeper into divergent cultural characteristics that teams may need to navigate.

Does Team Diversity Enhance Decision Making and Problem Solving?

In the Harvard Business Review article “Why Diverse Teams are Smarter," David Rock and Heidi Grant (2016) support the idea that increasing workplace diversity is a good business decision. A 2015 McKinsey report on 366 public companies found that those in the top quartile for ethnic and racial diversity in management were 35% more likely to have financial returns above their industry mean, and those in the top quartile for gender diversity were 15% more likely to have returns above the industry mean. Similarly, in a global analysis conducted by Credit Suisse, organizations with at least one female board member yielded a higher return on equity and higher net income growth than those that did not have any women on the board.

Additional research on diversity has shown that diverse teams are better at decision-making and problem-solving because they tend to focus more on facts, per the Rock and Grant article. A study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology showed that people from diverse backgrounds “might actually alter the behavior of a group’s social majority in ways that lead to improved and more accurate group thinking.” The diverse panels in the study raised more facts related to the case than homogeneous panels and made fewer factual errors while discussing available evidence. Another study noted cited in the article showed that diverse teams are “more likely to constantly reexamine facts and remain objective. They may also encourage greater scrutiny of each member’s actions, keeping their joint cognitive resources sharp and vigilant. By breaking up workforce homogeneity, you can allow your employees to become more aware of their own potential biases—entrenched ways of thinking that can otherwise blind them to key information and even lead them to make errors in decision-making processes.” In other words, when people are among homogeneous and like-minded (non-diverse) teammates, the team is susceptible to groupthink and may be reticent to think about opposing viewpoints since all team members are in alignment. In a more diverse team with a variety of backgrounds and experiences, the opposing viewpoints are more likely to come out and the team members feel obligated to research and address the questions that have been raised. Again, this enables a richer discussion and a more in-depth fact-finding and exploration of opposing ideas and viewpoints to solve problems.

Diversity in teams also leads to greater innovation. A Boston Consulting Group (BCG) article entitled “The Mix that Matters: Innovation through Diversity” explains a study in which they sought to understand the relationship between diversity in managers (all management levels) and innovation (Lorenzo et al., 2017). The key findings of this study show that:

- The positive relationship between management diversity and innovation is statistically significant—and thus companies with higher levels of diversity derive more revenue from new products and services.

- The innovation boost isn’t limited to a single type of diversity. The presence of managers who are either female or are from other countries, industries, or companies can cause an increase in innovation.

- Management diversity seems to have a particularly positive effect on innovation at complex companies—those that have multiple product lines or that operate in multiple industry segments.

- To reach its potential, gender diversity needs to go beyond tokenism. In the study, innovation performance only increased significantly when the workforce included more than 20% women in management positions. Having a high percentage of female employees doesn’t increase innovation if only a small number of women are managers.

- At companies with diverse management teams, openness to contributions from lower-level workers and an environment in which employees feel free to speak their minds are crucial for fostering innovation.

When you consider the impact that diverse teams have on decision-making and problem-solving—through the discussion and incorporation of new perspectives, ideas, and data—it is no wonder that the BCG study shows greater innovation. Team leaders need to reflect upon these findings during the early stages of team selection so that they can reap the benefits of having diverse voices and backgrounds.

Challenges and Best Practices for Working with Multicultural Teams

As globalization has increased over the last decades, workplaces have felt the impact of working within multicultural teams. The earlier section on team diversity outlined some of the benefits of working on diverse teams, and a multicultural group certainly qualifies as diverse. However, some key practices are recommended to those who are leading multicultural teams to navigate the challenges that these teams may experience.

People may assume that communication is the key factor that can derail multicultural teams, as participants may have different languages and communication styles. In the Harvard Business Review article “Managing Multicultural Teams,” Brett et al. (2006) outline four key cultural differences that can cause destructive conflicts in a team. The first difference is direct versus indirect communication, also known as high-context vs. low-context communication. Some cultures are very direct and explicit in their communication relying less on the context and more on the content of the communication to create meaning, while others are more indirect and ask questions rather than pointing out problems relying on the context to convey meaning rather the content of the communication. This difference can cause conflict because, at the extreme, the direct style may be considered offensive by some, while the indirect style may be perceived as unproductive and passive-aggressive in team interactions.

The second difference that multicultural teams may face is trouble with accents and fluency. When team members don’t speak the same language, there may be one language that dominates the group interaction—and those who don’t speak it may feel left out. The speakers of the primary language may feel that those members don’t contribute as much or are less competent. The third challenge is when there are differing attitudes toward hierarchy. Some cultures are very respectful of the hierarchy and will treat team members based on that hierarchy. Other cultures are more egalitarian and don’t observe hierarchical differences to the same degree. This may lead to clashes if some people feel that they are being disrespected and not treated according to their status. The final difference that may challenge multicultural teams is conflicting decision-making norms. Different cultures make decisions differently, and some will apply a great deal of analysis and preparation beforehand. Those cultures that make decisions more quickly (and need just enough information to make a decision) may be frustrated with the slow response and relatively longer thought process.

These cultural differences are good examples of how everyday team activities (decision-making, communication, interaction among team members) may become points of contention for a multicultural team if there isn’t an adequate understanding of everyone’s culture. The authors propose that there are several potential interventions to try if these conflicts arise. One simple intervention is adaptation, which is working with differences. This is best used when team members are willing to acknowledge the cultural differences and learn how to work with them. The next intervention technique is structural intervention, or reorganizing to reduce friction on the team. This technique is best used if there are unproductive subgroups or cliques within the team that need to be moved around. Managerial intervention is the technique of making decisions by management and without team involvement. This technique should be used sparingly, as it essentially shows that the team needs guidance and can’t move forward without management getting involved. Finally, exit is an intervention of last resort and is the voluntary or involuntary removal of a team member. If the differences and challenges have proven to be so great that an individual on the team can no longer work with the team productively, then it may be necessary to remove the team member in question.

Developing Cultural Intelligence

Some people seem to be innately aware of and able to work with cultural differences on teams and in their organizations. These individuals might be said to have cultural intelligence. Cultural intelligence is a competency and a skill that enables individuals to function effectively in cross-cultural environments. It develops as people become more aware of the influence of culture and more capable of adapting their behavior to the norms of other cultures. In the IESE Insight article entitled “Cultural Competence: Why It Matters and How You Can Acquire It," Lee and Liao (2015) assert that “multicultural leaders may relate better to team members from different cultures and resolve conflicts more easily. Their multiple talents can also be put to good use in international negotiations.” Multicultural leaders don’t have a lot of “baggage” from any one culture, and so are sometimes perceived as being culturally neutral. They are very good at handling diversity, which gives them a great advantage in their relationships with teammates.

To help people become better team members in a world that is increasingly multicultural, there are a few best practices that the authors recommend for honing cross-cultural skills. The first is to “broaden your mind”— expand your own cultural channels (travel, movies, books) and surround yourself with people from other cultures. This helps to raise your own awareness of the cultural differences and norms that you may encounter. Another best practice is to “develop your cross-cultural skills through practice” and experiential learning. You may have the opportunity to work or travel abroad — but if you don’t, then getting to know some of your company’s cross-cultural colleagues or foreign visitors will help you to practice your skills. Serving on a cross-cultural project team and taking the time to get to know and bond with your global colleagues is an excellent way to develop skills.

Once you have a sense of the different cultures and have started to work on developing your cross-cultural skills, another good practice is to “boost your cultural metacognition” and monitor your own behavior in multicultural situations. When you are in a situation in which you are interacting with multicultural individuals, you should test yourself and be aware of how you act and feel. Observe both your positive and negative interactions with people, and learn from them. Developing “cognitive complexity” is the final best practice for boosting multicultural skills. This is the most advanced, and it requires being able to view situations from more than one cultural framework. To see things from another perspective, you need to have a strong sense of emotional intelligence, empathy, and sympathy, and be willing to engage in honest communications.

In the Harvard Business Review article “Cultural Intelligence,” Earley and Mosakowski (2004) describe three sources of cultural intelligence that teams should consider if they are serious about becoming more adept in their cross-cultural skills and understanding. These sources, very simply, are head, body, and heart. One first learns about the beliefs, customs, and taboos of foreign cultures via the head. Training programs are based on providing this type of overview information—which is helpful but obviously isn’t experiential. This is the cognitive component of cultural intelligence. The second source, the body, involves more commitment and experimentation with the new culture. It is this physical component (demeanor, eye contact, posture, accent) that shows a deeper level of understanding of the new culture and its physical manifestations. The final source, the heart, deals with a person’s own confidence in their ability to adapt to and deal well with cultures outside of their own. Heart really speaks to one’s own level of emotional commitment and motivation to understand the new culture.

Earley and Mosakowski have created a quick assessment to diagnose cultural intelligence, based on these cognitive, physical, and emotional/motivational measures (i.e., head, body, heart). Please refer to the table below for a short diagnostic that allows you to assess your cultural intelligence.

Assessing Your Cultural Intelligence |

|

|---|---|

| Generally, scoring below 3 in any one of the three measures signals an area requiring improvement. Averaging over 4 displays strength in cultural intelligence. | |

| Adapted from “Cultural Intelligence,” Earley and Mosakowski, Harvard Business Review, October 2004 (Credit: OpenStax/CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) |

|

| Give your responses using a 1 to 5 scale where 1 means that you strongly disagree and 5 means that you strongly agree with the statement. | |

| Before I interact with people from a new culture, I wonder to myself what I hope to achieve. | |

| If I encounter something unexpected while working in a new culture, I use that experience to build new ways to approach other cultures in the future. | |

| I plan on how I am going to relate to people from a different culture before I meet with them. | |

| When I come into a new cultural situation, I can immediately sense whether things are going well or if things are going wrong. | |

| Add your total from the four questions above. | |

| Divide the total by 4. This is your Cognitive Cultural Quotient. | |

| It is easy for me to change my body language (posture or facial expression) to suit people from a different culture. | |

| I can alter my expressions when a cultural encounter requires it. | |

| I can modify my speech style by changing my accent or pitch of my voice to suit people from different cultures. | |

| I can easily change the way I act when a cross-cultural encounter seems to require it. | |

| Add your total from the four questions above. | |

| Divide the total by 4. This is your Cognitive Physical Quotient. | |

| I have confidence in my ability to deal well with people from different cultures than mine. | |

| I am certain that I can befriend people of different cultural backgrounds than mine. | |

| I can adapt to the lifestyle of a different culture with relative ease. | |

| I am confident in my ability to deal with an unfamiliar cultural situation or encounter. | |

| Add your total from the four questions above. | |

| Divide the total by 4. This is your Emotional/Motivational Cognitive Quotient. | |

Cultural intelligence is an extension of emotional intelligence. An individual must have a level of awareness and understanding of the new culture so that he or she can adapt to the style, pace, language, nonverbal communication, etc., and work together successfully with the new culture. A multicultural team can only find success if its members take the time to understand each other and ensure that everyone feels included. Multiculturalism and cultural intelligence are traits that are taking on increasing importance in the business world today. By following best practices and avoiding the challenges and pitfalls that can derail a multicultural team, a team can find great success and personal fulfillment well beyond the boundaries of the project or work engagement.

Digging in Deeper: Divergent Cultural Dimensions

Let’s dig in deeper by examining several points of divergence across cultures and consider how these dimensions might play out in organizations and in groups or teams.

Low-Power versus High-Power Distance

How comfortable are you with critiquing your boss’s decisions? If you are from a low-power distance culture, your answer might be “no problem.” In low-power distance cultures, according to Dutch researcher Geert Hofstede, people relate to one another more as equals and less as a reflection of dominant or subordinate roles, regardless of their actual formal roles as employee and manager, for example.

In a high-power distance culture, you would probably be much less likely to challenge the decision, to provide an alternative, or to give input. If you are working with people from a high-power distance culture, you may need to take extra care to elicit feedback and involve them in the discussion because their cultural framework may preclude their participation. They may have learned that less powerful people must accept decisions without comment, even if they have a concern or know there is a significant problem. Unless you are sensitive to cultural orientation and power distance, you may lose valuable information.

Individualistic versus Collectivist Cultures

People in individualistic cultures value individual freedom and personal independence, and cultures always have stories to reflect their values. People who grew up in the United States may recall the story of Superman or John McLean in the Diehard series, and note how one person overcomes all obstacles. Through personal ingenuity, despite challenges, one person rises successfully to conquer or vanquish those obstacles. Sometimes there is an assist, as in basketball or football, where another person lends a hand, but still the story repeats itself again and again, reflecting the cultural viewpoint.

When Hofstede explored the concepts of individualism and collectivism across diverse cultures (Hofstede, 1982, 2001, 2005), he found that in individualistic cultures like the United States, people perceived their world primarily from their own viewpoint. They perceived themselves as empowered individuals, capable of making their own decisions, and able to make an impact on their own lives.

Cultural viewpoint is not an either/or dichotomy, but rather a continuum or range. You may belong to some communities that express individualistic cultural values, while others place the focus on a collective viewpoint. Collectivist cultures (Hofstede, 1982), including many in Asia and South America, focus on the needs of the nation, community, family, or group of workers. Ownership and private property is one way to examine this difference. In some cultures, property is almost exclusively private, while others tend toward community ownership. The collectively owned resource returns benefits to the community. Water, for example, has long been viewed as a community resource, much like air, but that has been changing as businesses and organizations have purchased water rights and gained control over resources. Public lands, such as parks, are often considered public, and individual exploitation of them is restricted. Copper, a metal with a variety of industrial applications, is collectively owned in Chile, with profits deposited in the general government fund. While public and private initiatives exist, the cultural viewpoint is our topic. How does someone raised in a culture that emphasizes the community interact with someone raised in a primarily individualistic culture? How could tensions be expressed and how might interactions be influenced by this point of divergence?

Masculine versus Feminine Orientation

Hofstede describes the masculine-feminine dichotomy not in terms of whether men or women hold the power in a given culture, but rather the extent to which that culture values certain traits that may be considered masculine or feminine. Thus, “the assertive pole has been called ‘masculine’ and the modest, caring pole ‘feminine.’ The women in feminine countries have the same modest, caring values as the men; in the masculine countries, they are somewhat assertive and competitive, but not as much as the men, so that these countries show a gap between men’s values and women’s values” (Hofstede, 2009).

We can observe this difference in where people gather, how they interact, and how they dress. We can see it during business negotiations, where it may make an important difference in the success of the organizations involved. Cultural expectations precede the interaction, so someone who doesn’t match those expectations may experience tension. Business in the United States has a masculine orientation—assertiveness and competition are highly valued. In other cultures, such as Sweden, business values are more attuned to modesty (lack of self-promotion) and taking care of society’s weaker members. This range of differences is one aspect of intercultural communication that requires significant attention when the business communicator enters a new environment.

Uncertainty-Accepting Cultures versus Uncertainty-Rejecting Cultures

When we meet each other for the first time, we often use what we have previously learned to understand our current context. We also do this to reduce our uncertainty. Some cultures, such as the United States and Britain, are highly tolerant of uncertainty, while others go to great lengths to reduce the element of surprise. Cultures in the Arab world, for example, are high in uncertainty avoidance; they tend to be resistant to change and reluctant to take risks. Whereas a U.S. business negotiator might enthusiastically agree to try a new procedure, an Egyptian counterpart would likely refuse to get involved until all the details are worked out.

Short-Term versus Long-Term Orientation

Do you want your reward right now or can you dedicate yourself to a long-term goal? You may work in a culture whose people value immediate results and grow impatient when those results do not materialize. Geert Hofstede discusses this relationship of time orientation to a culture as a “time horizon,” and it underscores the perspective of the individual within a cultural context. Many countries in Asia, influenced by the teachings of Confucius, value a long-term orientation, whereas other countries, including the United States, have a more short-term approach to life and results. Native American cultures are known for holding a long-term orientation, as illustrated by the proverb attributed to the Iroquois Confederacy that decisions require contemplation of their impact seven generations removed.

If you work within a culture that has a short-term orientation, you may need to place greater emphasis on reciprocation of greetings, gifts, and rewards. For example, if you send a thank-you note the morning after being treated to a business dinner, your host will appreciate your promptness. While there may be respect for tradition, there is also an emphasis on personal representation and honor, a reflection of identity and integrity. Personal stability and consistency are also valued in a short-term-oriented culture, contributing to an overall sense of predictability and familiarity.

Long-term orientation is often marked by persistence, thrift and frugality, and an order to relationships based on age and status. A sense of shame for the family and community is also observed across generations. What an individual does reflects on the family and is carried by immediate and extended family members.

Time Orientation

Edward T. Hall and Mildred Reed Hall (1987) state that monochronic time-oriented cultures consider one thing at a time, whereas polychronic time-oriented cultures schedule many things at one time, and time is considered in a more fluid sense. In monochromatic time, interruptions are to be avoided, and everything has its own specific time. Even the multitasker from a monochromatic culture will, for example, recognize the value of work first before play or personal time. The United States, Germany, and Switzerland are often noted as countries that value a monochromatic time orientation.

Polychromatic time looks a little more complicated, with business and family mixing with dinner and dancing. Greece, Italy, Chile, and Saudi Arabia are countries where one can observe this perception of time; business meetings may be scheduled at a fixed time, but when they actually begin may be another story. Also, note that the dinner invitation for 8 p.m. may in reality be more like 9 p.m. If you were to show up on time, you might be the first person to arrive and find that the hosts are not quite ready to receive you.

When in doubt, always ask before the event; many people from polychromatic cultures will be used to foreigner’s tendency to be punctual, even compulsive, about respecting established times for events. The skilled business communicator is aware of this difference and takes steps to anticipate it. The value of time in different cultures is expressed in many ways, and your understanding can help you communicate more effectively.

Review & Reflection Questions

- Why are diverse teams better at decision-making and problem-solving?

- What are some of the challenges that multicultural teams face?

- How might you further cultivate your own cultural intelligence?

- What are some potential points of divergence between cultures? How might these play out in teams?

References

- Brett, J., Behfar, K., Kern, M. (2006, November). Managing multicultural teams. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2006/11/managing-multicultural-teams

- Dodd, C. (1998). Dynamics of intercultural communication (5th ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Earley, P.C., & Mosakowski, E. (2004, October). Cultural intelligence. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2004/10/cultural-intelligence

- Hall, M. R., & Hall, E. T. (1987). Hidden differences: Doing business with the Japanese. New York, NY: Doubleday.

- Hofstede, G. (1982). Culture’s consequences (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede, G. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Lee, Y-T., & Liao, Y. (2015). Cultural competence: Why it matters and how you can acquire it. IESE Insight. https://www.ieseinsight.com/doc.aspx?id=1733&ar=20

- Lorenzo, R., Yoigt, N., Schetelig, K., Zawadzki, A., Welpe, I., & Brosi, P. (2017). The mix that matters: Innovation through diversity. Boston Consulting Group. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2017/people-organization-leadership-talent-innovation-through-diversity-mix-that-matters.aspx

- Rock, D., & Grant, H. (2016, November 4). Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter

Author & Attribution

The sections "How Does Team Diversity Enhance Decision Making and Problem Solving?" and "Challenges and Best Practices for Working with Multicultural Teams" are adapted from Black, J.S., & Bright, D.S. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/organizational-behavior/. Access the full chapter for free here. The content is available under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license.

The section "Digging in Deeper: Divergent Cultural Dimensions" is adapted from "Divergent Cultural Characteristics" in Business Communication for Success from the University of Minnesota. The book was adapted from a work produced and distributed under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA) by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution. This work is made available under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

Learning Objectives

- Describe how diversity can enhance decision-making and problem-solving

- Identify challenges and best practices for working with multicultural teams

- Discuss divergent cultural characteristics and list several examples of such characteristics in the culture(s) you identify with

Decision-making and problem-solving can be much more dynamic and successful when performed in a diverse team environment. The multiple diverse perspectives can enhance both the understanding of the problem and the quality of the solution. Yet, working in diverse teams can be challenging given different identities, cultures, beliefs, and experiences. In this chapter, we will discuss the effects of team diversity on group decision-making and problem-solving, identify best practices and challenges for working in and with multicultural teams, and dig deeper into divergent cultural characteristics that teams may need to navigate.

Does Team Diversity Enhance Decision Making and Problem Solving?

In the Harvard Business Review article “Why Diverse Teams are Smarter," David Rock and Heidi Grant (2016) support the idea that increasing workplace diversity is a good business decision. A 2015 McKinsey report on 366 public companies found that those in the top quartile for ethnic and racial diversity in management were 35% more likely to have financial returns above their industry mean, and those in the top quartile for gender diversity were 15% more likely to have returns above the industry mean. Similarly, in a global analysis conducted by Credit Suisse, organizations with at least one female board member yielded a higher return on equity and higher net income growth than those that did not have any women on the board.

Additional research on diversity has shown that diverse teams are better at decision-making and problem-solving because they tend to focus more on facts, per the Rock and Grant article. A study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology showed that people from diverse backgrounds “might actually alter the behavior of a group’s social majority in ways that lead to improved and more accurate group thinking.” The diverse panels in the study raised more facts related to the case than homogeneous panels and made fewer factual errors while discussing available evidence. Another study noted cited in the article showed that diverse teams are “more likely to constantly reexamine facts and remain objective. They may also encourage greater scrutiny of each member’s actions, keeping their joint cognitive resources sharp and vigilant. By breaking up workforce homogeneity, you can allow your employees to become more aware of their own potential biases—entrenched ways of thinking that can otherwise blind them to key information and even lead them to make errors in decision-making processes.” In other words, when people are among homogeneous and like-minded (non-diverse) teammates, the team is susceptible to groupthink and may be reticent to think about opposing viewpoints since all team members are in alignment. In a more diverse team with a variety of backgrounds and experiences, the opposing viewpoints are more likely to come out and the team members feel obligated to research and address the questions that have been raised. Again, this enables a richer discussion and a more in-depth fact-finding and exploration of opposing ideas and viewpoints to solve problems.

Diversity in teams also leads to greater innovation. A Boston Consulting Group (BCG) article entitled “The Mix that Matters: Innovation through Diversity” explains a study in which they sought to understand the relationship between diversity in managers (all management levels) and innovation (Lorenzo et al., 2017). The key findings of this study show that:

- The positive relationship between management diversity and innovation is statistically significant—and thus companies with higher levels of diversity derive more revenue from new products and services.

- The innovation boost isn’t limited to a single type of diversity. The presence of managers who are either female or are from other countries, industries, or companies can cause an increase in innovation.

- Management diversity seems to have a particularly positive effect on innovation at complex companies—those that have multiple product lines or that operate in multiple industry segments.

- To reach its potential, gender diversity needs to go beyond tokenism. In the study, innovation performance only increased significantly when the workforce included more than 20% women in management positions. Having a high percentage of female employees doesn’t increase innovation if only a small number of women are managers.

- At companies with diverse management teams, openness to contributions from lower-level workers and an environment in which employees feel free to speak their minds are crucial for fostering innovation.

When you consider the impact that diverse teams have on decision-making and problem-solving—through the discussion and incorporation of new perspectives, ideas, and data—it is no wonder that the BCG study shows greater innovation. Team leaders need to reflect upon these findings during the early stages of team selection so that they can reap the benefits of having diverse voices and backgrounds.

Challenges and Best Practices for Working with Multicultural Teams

As globalization has increased over the last decades, workplaces have felt the impact of working within multicultural teams. The earlier section on team diversity outlined some of the benefits of working on diverse teams, and a multicultural group certainly qualifies as diverse. However, some key practices are recommended to those who are leading multicultural teams to navigate the challenges that these teams may experience.

People may assume that communication is the key factor that can derail multicultural teams, as participants may have different languages and communication styles. In the Harvard Business Review article “Managing Multicultural Teams,” Brett et al. (2006) outline four key cultural differences that can cause destructive conflicts in a team. The first difference is direct versus indirect communication, also known as high-context vs. low-context communication. Some cultures are very direct and explicit in their communication relying less on the context and more on the content of the communication to create meaning, while others are more indirect and ask questions rather than pointing out problems relying on the context to convey meaning rather the content of the communication. This difference can cause conflict because, at the extreme, the direct style may be considered offensive by some, while the indirect style may be perceived as unproductive and passive-aggressive in team interactions.

The second difference that multicultural teams may face is trouble with accents and fluency. When team members don’t speak the same language, there may be one language that dominates the group interaction—and those who don’t speak it may feel left out. The speakers of the primary language may feel that those members don’t contribute as much or are less competent. The third challenge is when there are differing attitudes toward hierarchy. Some cultures are very respectful of the hierarchy and will treat team members based on that hierarchy. Other cultures are more egalitarian and don’t observe hierarchical differences to the same degree. This may lead to clashes if some people feel that they are being disrespected and not treated according to their status. The final difference that may challenge multicultural teams is conflicting decision-making norms. Different cultures make decisions differently, and some will apply a great deal of analysis and preparation beforehand. Those cultures that make decisions more quickly (and need just enough information to make a decision) may be frustrated with the slow response and relatively longer thought process.

These cultural differences are good examples of how everyday team activities (decision-making, communication, interaction among team members) may become points of contention for a multicultural team if there isn’t an adequate understanding of everyone’s culture. The authors propose that there are several potential interventions to try if these conflicts arise. One simple intervention is adaptation, which is working with differences. This is best used when team members are willing to acknowledge the cultural differences and learn how to work with them. The next intervention technique is structural intervention, or reorganizing to reduce friction on the team. This technique is best used if there are unproductive subgroups or cliques within the team that need to be moved around. Managerial intervention is the technique of making decisions by management and without team involvement. This technique should be used sparingly, as it essentially shows that the team needs guidance and can’t move forward without management getting involved. Finally, exit is an intervention of last resort and is the voluntary or involuntary removal of a team member. If the differences and challenges have proven to be so great that an individual on the team can no longer work with the team productively, then it may be necessary to remove the team member in question.

Developing Cultural Intelligence