Chapter 5: Public Policy Rulemaking and Regulations

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was founded in response to growing concerns about the state of the environment and public health in the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The catalyst for its creation was the increasing recognition of pollution and its adverse effects on air, water, and land. Prior to the EPA’s establishment, environmental protection efforts were fragmented, with various federal agencies handling different aspects of environmental regulation.

In 1970, President Richard Nixon signed an executive reorganization plan that established the EPA as a consolidated agency responsible for coordinating and overseeing environmental policies and regulations. The order was ratified by congress and the agency officially began operations on December 2, 1970. Its primary mission was, and remains, to protect human health and the environment by enforcing and implementing laws and regulations related to air and water quality, hazardous waste management, chemical safety, and more. The EPA’s formation marked a significant turning point in environmental policy in the United States, leading to the development of landmark legislation such as the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and others that set stringent standards for pollution control and environmental protection. The EPA’s role has since been pivotal in addressing a wide range of environmental challenges and promoting sustainability and responsible resource management.

If you are of a certain age, or if you have had nostalgic teachers, you may have watched any number of SchoolHouse Rock-type videos that told you that the legislative branch of government is for making laws, the executive branch is for enforcing laws, and the judicial branch is for reviewing laws. This isn’t wrong…it is just…incomplete.

The EPA’s actions are strictly bound by statutes, which are the laws enacted by Congress. These statutes not only define the agency’s powers and responsibilities but also establish its budgetary limits by authorizing the annual expenditures the agency can make to execute the approved statutes. The EPA possesses the authority to issue regulations. A regulation is a set of requirements issued by a federal government agency to implement laws passed by Congress. When an agency issues a regulation, it follows a mandatory process. The basic process is that a federal agency first proposes a regulation and invites public comments on it. The agency then considers the public comments and issues a final regulation, which may include revisions that respond to the comments. The process is designed to make the agency’s views transparent and give the public and interested parties a chance to submit their views on a proposed regulation before it is finalized. The participation of the public plays a vital role in the rulemaking procedure by offering valuable insights into the potential consequences of a proposed regulation.

Thus, agencies such as the EPA have both enforcement and lawmaking duties. The EPA has passed numerous regulations through the regulatory process to address various environmental and public health concerns. Here are some specific examples of EPA regulations:

The Clean Air Act (CAA) was passed by Congress, however the EPA was authorized to set regulations such as:

- National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS): The EPA sets standards for common air pollutants such as ozone, particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and lead. These standards dictate the maximum allowable concentration of these pollutants in the air to protect public health and the environment.

- Clean Power Plan: This regulation aimed to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, addressing climate change concerns by setting state-specific emission reduction targets.

- Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS): MATS limits emissions of hazardous air pollutants, including mercury, from coal and oil-fired power plants to protect public health and the environment.

The Clean Water Act (CWA) was passed by Congress, however the EPA was authorized to set regulations such as:

- Effluent Limitation Guidelines (ELGs): ELGs establish standards for the discharge of pollutants from various industrial sectors, such as the pulp and paper industry, to ensure that water bodies are protected from contamination.

- Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs): TMDLs are developed to address impaired water bodies by specifying the maximum amount of a particular pollutant that can enter a water body while still meeting water quality standards.

- National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES): NPDES permits regulate discharges from point sources, such as industrial facilities and wastewater treatment plants, to prevent water pollution.

The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) was passed by Congress, however the EPA was authorized to set regulations such as:

- Chemical Substance Inventory: The EPA maintains the TSCA Chemical Substance Inventory, which lists all chemicals in commerce and allows the agency to track and regulate them.

- Risk Evaluation Framework: TSCA requires the EPA to assess and regulate chemicals for potential risks to human health and the environment. The EPA has developed a framework for evaluating and managing these risks.

The list could go on and on and a similar list could be created for any of the agencies or departments in the federal government and for most in state governments as well.

One perspective for understanding public policy involves viewing it as the overarching strategic framework employed by the government to fulfill its responsibilities. To put it more formally, it represents a relatively stable collection of deliberate governmental actions that address issues pertinent to specific segments of society. This characterization proves valuable in elucidating both the nature and scope of public policy. Firstly, public policy serves as a guiding framework for legislative actions that endure over extended periods, transcending short-term fixes or isolated legislative measures. Furthermore, policy formulation is not an arbitrary process, nor is it typically shaped solely by the electoral pledges of a single elected official, including the President. Instead, policy outcomes predominantly result from extensive deliberation, negotiation, and refinement spanning several years, culminating in finalization after input from multiple governmental institutions, interest groups, and the general public.

Additionally, public policy primarily addresses concerns of significance to broad sections of society, differentiating it from issues of personal interest or relevance to small, specific groups. While governments frequently engage with individual actors, such as citizens, corporations, or other nations, and may even enact specialized legislation (private bills) that confer specific privileges upon particular entities, public policy exclusively encompasses matters of broad societal interest or those with direct or indirect impacts on society as a whole. For instance, liquidating the debts of an individual does not fall within the realm of public policy, whereas establishing a mechanism for loan forgiveness available to specific categories of borrowers (such as those contributing to the public good by becoming educators) unquestionably qualifies as a subject of public policy.

Finally, it is crucial to recognize that public policy transcends mere government actions; it encompasses the behaviors and consequences that result from governmental intervention. Policy can also manifest when the government takes no action at all, even as circumstances or public sentiment undergo changes. For instance, much of the discourse surrounding gun safety policy in the United States centers on Congress’s reluctance to act, even in the face of public support for some modifications in gun policy. Indeed, one of the most recent significant alterations occurred in 2004, when congressional inaction led to the expiration of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban and later when public sentiment was in favor of action, such as in 2012 after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting.

At its core, public policy involves the intricate decisions surrounding the distribution, allocation, and accessibility of public, communal, and toll goods within a given society. While the particulars of each policy are contingent on specific circumstances, policymakers universally grapple with two overarching inquiries: a) who bears the financial burdens associated with creating and maintaining these goods, and b) who reaps the advantages of their provision? In the realm of private goods, which are exchanged within a marketplace, the costs and benefits directly accrue to the parties involved in the transaction. For instance, your landlord benefits from the rent you pay, while you gain the advantage of having a place to reside. Conversely, non-private goods such as road infrastructure, waterways, and national parks are managed and overseen by entities distinct from the individual owners, affording policymakers the latitude to determine the beneficiaries and funders of these goods.

Rulemaking and Regulations

The executive branches of government play a significant role in making and implementing policy through a process known as rulemaking. While the primary responsibility for making policy lies with the legislative branch (Congress at the federal level, state legislatures and city councils more locally), the executive branch is tasked with enforcing these laws. Rulemaking allows executive agencies to create detailed regulations and guidelines necessary for implementing and enforcing the broader statutes passed by Congress.

Rulemaking at the federal level begins with the delegation of authority from Congress to various federal agencies. This delegation of authority is foundational to the administrative state and is often embedded within the laws that Congress passes.

When Congress passes a statute, it typically outlines the broader goals, objectives, and principles that it intends to address through the legislation. However, these laws are often intentionally broad and may not provide the detailed, day-to-day operational guidance required for effective implementation. This is where the concept of enabling legislation comes into play. Enabling legislation, or enabling statutes, are provisions within congressional legislation that explicitly authorize federal agencies to create regulations and rules within specific areas or subject matters. These statutes grant agencies the legal authority and framework to develop the detailed rules and regulations necessary to operationalize and enforce the law effectively.

Here’s a more detailed breakdown of how this delegation of authority works:

- Broad Legislation: Congress drafts and passes broad legislation to address complex issues or policy objectives. For example, Congress might pass environmental protection laws to safeguard the environment without specifying every technical detail.

- Delegation of Rulemaking Authority: Within these laws, Congress includes provisions that delegate rulemaking authority to relevant federal agencies. These provisions grant agencies the power to develop regulations that further define and clarify the law’s requirements. Congress provides a framework within which agencies can create these rules.

- Agency Expertise: Congress recognizes that federal agencies often possess the specialized expertise needed to translate legislative goals into actionable rules. For instance, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has experts in environmental science who can create regulations based on the goals set by Congress.

- Rule Development: Once delegated this authority, agencies embark on the rulemaking process. They publish proposed rules, seek public input, and analyze the potential impact. The agency’s goal is to develop rules that align with the statutory framework, fill in the details, and address practical implementation issues.

- Public Input: Throughout the rulemaking process, agencies often seek public input through public comment periods. This allows stakeholders, including affected industries, advocacy groups, and the general public, to provide feedback and raise concerns. Agencies are required to consider this feedback.

- Final Rule: After considering public input and making necessary revisions, agencies publish the final rule. This document provides the specific regulations and requirements that organizations and individuals must follow to comply with the law.

- Implementation and Enforcement: Once the final rule is in place, the agency is responsible for implementing and enforcing it. This includes monitoring compliance, investigating violations, and taking enforcement actions when necessary.

Enabling statutes, therefore, serve as the bridge between broad legislative intent and the practical, detailed rules needed for effective governance. They empower agencies to act within their areas of expertise and authority, ensuring that federal laws can be effectively put into practice while maintaining accountability and transparency through the rulemaking process.

At the federal level, the rulemaking process is governed by the Administrative Procedures Act of 1946. The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) is a foundational federal statute in the United States that governs the procedures and practices of administrative agencies. Enacted in 1946, the APA sets out the framework for how federal agencies create and promulgate regulations, conduct adjudications, and engage with the public. It aims to ensure transparency, fairness, and accountability in the administrative rulemaking process, providing a structured mechanism for public participation, judicial review, and the protection of individual rights when dealing with federal agencies. The APA’s provisions have a profound impact on the regulatory landscape, shaping how agencies operate and interact with the public, businesses, and other stakeholders, ultimately influencing the implementation of federal laws and regulations across a wide range of policy areas.

One of the areas covered by the APA is the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) and public comment period requirements. Once an agency identifies the need for a new regulation or an amendment to an existing one, it initiates the rulemaking process by publishing a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) in a publication called the Federal Register. The NPRM outlines the agency’s proposed regulation, its goals, and its potential impact. The NPRM provides interested parties, including the public, affected industries, advocacy groups, and experts, an opportunity to comment on the proposed regulation. This public comment period can vary in length but typically lasts 30 to 60 days, allowing stakeholders to provide input, feedback, and concerns.

Agencies carefully review and consider the comments received during the public comment period. They may make revisions to the proposed rule based on the feedback and address any significant concerns raised by stakeholders. Then, after completing the analysis and revisions, the agency publishes the final rule in the Federal Register. The final rule outlines the regulation’s provisions, compliance requirements, and the date it becomes effective.

It’s important to note that while rulemaking allows the executive branch to create detailed regulations, these regulations must be consistent with the broader statutes passed by Congress. Courts can review agency actions to ensure they are within the scope of the authority granted by Congress and do not exceed their statutory powers.

Rulemaking is a fundamental aspect of how the executive branch carries out its responsibilities in enforcing and implementing federal laws. It allows agencies to provide specific guidance and requirements to various industries and stakeholders, ensuring that the intent of Congress is realized in practice.

Types of Policy

In 1964, Theodore Lowi proposed a framework for categorizing policies based on the extent to which costs and benefits are concentrated among a select few or diffused across a broader population. The first of these categories is known as distributive policy. Distributive policy typically involves the aggregation of contributions or resources from a wide array of individuals but funnels direct benefits toward a comparatively limited subset. For example, the development of highways often falls under distributive policy, where the costs are spread widely among taxpayers, but the immediate benefits are concentrated among those who utilize the roads. Distributive policy also arises when society recognizes the collective advantages of individuals gaining access to private goods, such as higher education, which yields long-term benefits, even though the initial cost may be prohibitive for the average citizen.

Consider the implementation of a distributive policy in the context of a government- funded initiative to enhance the accessibility of broadband internet in rural areas. In this scenario, the government aims to bridge the digital divide by providing high-speed internet infrastructure to underserved and remote regions. The costs associated with developing and maintaining this broadband network are substantial, encompassing infrastructure installation, ongoing maintenance, and operational expenses. These costs are collected through a combination of funding mechanisms, including federal grants, state contributions, and potentially user fees.

While the costs are distributed broadly among taxpayers, the immediate and direct benefits of this broadband expansion predominantly accrue to the residents and businesses in these rural areas. They gain access to high-speed internet, which opens doors to improved education, healthcare, economic opportunities, and connectivity. As a result, the distributive policy aligns with the objective of reducing disparities and enhancing the quality of life for those in underserved regions. This approach reflects the essence of distributive policy, wherein resources are collected from a larger population to concentrate benefits on a specific group or geographic area to address disparities and foster societal equity.

Other examples of distributive policy include agricultural subsidies, social security programs, public education, and public health initiatives, where costs are shared across taxpayers, but primary beneficiaries are distinct, such as farmers, retirees, students, or low-income individuals. These policies aim to address disparities, promote equity, and enhance societal well-being by redistributing resources to those in need, ensuring access to essential services, and fostering economic stability.

The next category in Lowi’s framework is regulatory policy. According to Lowi, regulatory policy differs from distributive policy in that it involves concentrated costs and dispersed benefits. In regulatory policy, a limited number of individuals or groups bear the burdens or expenses, while its advantages are intended to be broadly shared across society. Regulatory policies allow the government to compel certain beneficial behaviors from individuals or groups while discouraging other behaviors. Government regulatory policies involve the implementation of rules by government actors, rules that are backed by the law. Regulatory policies place constraints on unacceptable individual and group behaviors.

Regulatory policies are particularly effective in controlling and safeguarding public and shared resources. Examples of regulatory policies encompass environmental regulations to safeguard the environment, financial regulations to ensure the stability of financial markets, and workplace safety regulations to protect workers. These policies often arise in response to issues like industrial abuses, public health concerns, or economic crises, aiming to prevent harmful practices and promote transparency. Such regulatory measures became increasingly prominent in the United States during the early 20th century, driven by exposés by investigative journalists and societal demands for accountability, resulting in the establishment of government agencies like the FDA and regulatory frameworks like the Clean Air Act.

The final category in Lowi’s original framework is redistributive policy. As its name suggests, its primary objective is redistributing resources within society from one segment to another. According to Lowi, these policies involve the concentration of both costs and benefits, but these costs and benefits are dispersed among different groups. The overarching aim of redistributive policies is often to achieve a form of societal fairness where income and wealth and even status can be transferred from one group to another to ensure that everyone can attain at least a basic standard of living. Typically, the burden of funding redistributive policies falls on the affluent and middle- class citizens through taxation, with the resulting resources directed toward programs that provide assistance to those with lower incomes or in need.

Redistributive policies tend to generate more controversy compared to distributive policies, primarily because they involve providing benefits to specific groups while potentially imposing costs on others. Federal welfare programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) serve as contentious examples of redistributive public policy initiatives. Advocates of these programs contend that SNAP and TANF offer crucial support to economically disadvantaged Americans. Conversely, critics argue that these policies effectively redirect taxpayer funds from the working class to those who are not actively employed.

Notably, despite the inherent contentiousness surrounding redistributive policies, they are frequently employed when policymakers perceive disparities in economic growth. Student loan forgiveness proposals exemplify redistributive policy and will likely remain a subject of debate for the foreseeable future. Proponents of forgiving student loans contend that this action would promote greater income equality, potentially reducing poverty rates and stimulating economic growth. Conversely, opponents say that such legislation isn’t fair to people who don’t have loans and might inadvertently exacerbate poverty by increasing inflation.

Other notable examples of redistributive policies include universal healthcare, Head Start, Pell Grants, Medicaid, social welfare programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Supplementary Nutritional Aid Program (SNAP), the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Section 8 housing initiatives.

Later on, Lowi added a fourth designation, constituent policy. Constituent policies involve the creation and regulation of government agencies and can also refer to policies that establish the way a government functions. They are primarily concerned with the structural aspects of governance, including the creation of government agencies, often falling within the executive branch. These agencies are tasked with enforcing statutory laws passed by Congress. Constituent policies typically arise in response to external events or challenges. For instance, in January of 2020, President Donald Trump established the White House Coronavirus Task Force to enhance his administration’s ability to respond to the virus. This task force set policy a number of times by either refining or overruling regulations proposed by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Examples include ending the cruise ship “no sail” directive early and overruling a proposal to require masks on all public and commercial transportation.

Constituent policies extend to various areas, including law enforcement, fiscal policy development, and the regulatory functions of the public sector. Some of these policies pertain to procedural matters, such as defining the roles and functions of government agencies. For example, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration’s mission focuses on reducing drug use and assisting Americans dealing with mental health issues. In this instance, the constituent policy involved specifying the agency’s functions and objectives. It’s worth noting that the concept of constituent policy has evolved to include policies initiated not only by Congress or executive branch agencies but also by citizens or interest groups seeking to influence government actions.

Another example of constituent policy was in 2019 when the state legislature in Arkansas approved a bill backed by the governor aimed at streamlining the government’s bureaucratic structure. The primary goal was to reduce the number of cabinet agencies significantly, going from 42 to 15. They also moved all 200 of the state’s boards and commissions into the remaining agencies. Their stated objective was to create a more efficient and organized flow chart within the government.

Policy Process

Several actors are involved in the policy cycle in the United States. These actors include:

- Government: The government, both the elected officials and the appointed and civil service employees, plays a crucial role in the policy cycle, particularly in the adoption and implementation stages. The government is responsible for passing laws, regulations, and other policy directives and implementing them through various agencies and programs.

- Interest Groups: Interest groups represent the interests of specific groups or communities and often play a significant role in the agenda-setting and policy formulation stages. Interest groups may lobby government officials, conduct research, and engage in public awareness campaigns to influence policy outcomes.

- Experts and Academics: Experts and academics provide technical expertise and analysis in the policy formulation and evaluation stages. They may conduct research, provide policy recommendations, and evaluate policy outcomes.

- Media: The media plays a critical role in shaping public opinion and influencing the agenda-setting stage of the policy cycle. The media may report on specific issues, highlight policy failures, and provide a platform for interest groups to promote their views.

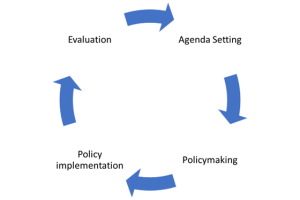

One way to conceive of the policy process is to think of it as made up of four consecutive stages: agenda setting, policy making, policy implementation, and evaluation (see Fig. 5.1). However, navigating this process can be challenging due to the substantial number of existing government issues (the continuing agenda) and numerous new proposals vying for attention simultaneously.

Agenda Setting

Agenda setting, the pivotal initial stage, encompasses two subphases: problem definition and identifying solutions. Problem definition represents the initial step in addressing societal challenges and translating them into actionable policy initiatives. This multifaceted stage involves identifying and characterizing issues that warrant governmental attention and intervention. Problem definition serves as the foundation upon which policy development, implementation, and evaluation are built. If there are many traffic accidents at a particular intersection in your town, is the problem the intersection itself (poor visibility, no signaling, bad design, etc.) or the drivers (speed, attention, adherence to road laws, etc.)? Identifying what the problem actually is matters a great deal when it comes to fixing that problem.

The process of problem definition begins with recognizing and acknowledging societal concerns. Not every issue automatically finds its way onto the policy agenda. Constraints in attention, resources, and politics will necessitate a strategic approach to highlight specific problems deserving of policy attention. Consequently, advocates, policymakers, researchers, and interest groups play a pivotal role in identifying issues and framing them persuasively.

Effective problem definition involves several key elements:

- 1. Issue Framing: How an issue is framed significantly influences its potential to gain traction on the policy agenda. Framing involves presenting the problem in a manner that emphasizes its significance, urgency, and potential impact. For example, when addressing healthcare reform, framing the issue as a matter of “access to affordable healthcare” resonates differently than framing it solely as “healthcare costs.”

- Evidentiary Support: Problem definition benefits from robust data and evidence. Quantitative and qualitative research, expert analyses, and empirical studies provide the foundation for substantiating the existence and severity of a problem. Data-driven problem definition enhances credibility and fosters consensus among stakeholders.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Engaging various stakeholders, including affected communities, advocacy groups, and subject matter experts, is essential in shaping the problem’s definition. Diverse perspectives contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the issue and its potential solutions.

- Political Dynamics: Recognizing the political landscape and the priorities of decision-makers is vital in navigating problem definition. Policymakers often prioritize issues that align with their constituents’ interests or political agendas.

- Policy Alternatives: Problem definition is intertwined with the exploration of potential policy alternatives. Identifying the problem inherently prompts discussions about potential solutions, leading to debates, negotiations, and the development of policy options.

- Social and Cultural Context: The social and cultural context in which a problem arises can significantly influence how it is defined. Cultural norms, values, and public opinion play a role in shaping perceptions of problems and acceptable policy responses.

Ultimately, problem definition is the gateway through which societal concerns become political issues, fueling the subsequent stages of the policy process. Effective problem definition is both an art and a science, requiring persuasive communication, empirical support, stakeholder engagement, and political savvy. It sets the stage for the policy agenda, shaping the direction of public policy and governance.

The second subphase involves identifying possible solutions to address the problem. While policymakers may agree on the problem, choosing the best solution can be contentious. It isn’t particularly controversial to say that rising levels of childhood diabetes is a problem, however potential solutions range from implementing nutritional requirements to increasing medicaid access to doing nothing and saying that it is a private health matter that should be handled by families. Identifying solutions within the policy process is a pivotal stage that acts as a crucial link between recognizing a problem and formulating effective policy responses. During this phase, policymakers, experts, and stakeholders engage in a comprehensive exploration of potential strategies and interventions aimed at addressing the identified issue. This process is characterized by its complexity and multifaceted nature, encompassing various key elements.

Research and analysis form the foundation of identifying solutions. Policymakers and experts undertake rigorous research and data analysis to gain a deep understanding of the problem’s causes and consequences. This knowledge informs the development of targeted solutions that are evidence-based and well-informed. Cost-Benefit analysis can play a crucial role in evaluating the financial implications, resource requirements, and potential outcomes associated with each proposed solution. This analysis aids in prioritizing solutions based on their feasibility and expected impact. Legal and ethical considerations ensure that the proposed solutions align with existing legal frameworks and ethical principles. Policymakers verify that interventions comply with relevant laws and regulations while also taking ethical considerations, such as equity and social justice, into account.

The political feasibility of each possible solution is assessed, considering factors like legislative support, executive leadership, and potential opposition from interest groups. The political landscape significantly influences the identification of feasible solutions.

Consider this, the headquarters of Walmart is located in Northwest Arkansas. If you were a representative in that district and were working on potential solutions to poverty, do you think that raising the minimum wage would be a politically feasible option for you? Probably not.

Public Opinion and Acceptance are also vital for successful policy implementation. Policymakers gauge public opinion through various means, including surveys and public consultations. Solutions that align with public preferences are more likely to garner support. Stakeholder Engagement is critical in this phase, as it involves a diverse array of stakeholders. These stakeholders may include affected communities, advocacy groups, industry representatives, and subject matter experts. Their unique insights and perspectives enrich the pool of potential solutions.

Policymaking

In the next phase, the policymaking phase, elected representatives deliberate on the proposed solution and decide whether to pass it. This represents the point at which proposed solutions transform into concrete policies that address societal issues. This phase involves a series of deliberations, negotiations, and decision-making processes within government institutions.

Policymaking primarily occurs within legislative bodies, such as the U.S. Congress, state legislatures, or city councils where elected representatives debate and formulate policies. The legislative process involves several stages, including the introduction of bills, committee reviews, floor debates, and final votes. Politics plays a significant role in policymaking. The policymaking stage is marked by negotiations, compromises, and jockeying for support among legislators. Political parties, interest groups, and advocacy coalitions exert influence on the process, attempting to shape policy outcomes in alignment with their objectives. The balance of power and partisan considerations often affect which policies move forward and which are stalled. Policymakers work together to craft, amend, and refine legislation until enough support is garnered to pass a law.

Policymakers rely on policy analysis to inform their decisions. This involves assessing the potential impacts, costs, benefits, and feasibility of proposed policies. Analysts provide legislators with research, data, and evidence-based recommendations to guide their choices. This rigorous analysis helps ensure that policies are well-informed and have a higher chance of achieving their intended goals. Public engagement is also a critical component of the policymaking stage. Legislators seek input from constituents through public hearings, town halls, and feedback mechanisms. Advocacy groups and concerned citizens have the opportunity to voice their opinions, present evidence, and influence the policy development process. Public input enhances transparency and democratic accountability.

Implementation

After enactment, government agencies are responsible for policy implementation. The implementation stage of the policy process is the phase in which policies are put into action, transforming them from abstract ideas into tangible programs, actions, or regulations. This stage involves a series of activities and decisions aimed at executing the policy, achieving its goals, and addressing the issues it was designed to tackle.

Effective policy implementation begins with careful planning. Government agencies or departments responsible for executing the policy develop comprehensive implementation plans. These plans outline specific steps, timelines, resource allocation, and responsibilities. Clear planning ensures that the policy’s objectives are translated into actionable tasks. Adequate resources are essential for successful implementation. Policymakers allocate the necessary financial, human, and technological resources to support the policy’s execution. This includes budget appropriations, staffing decisions, and procurement of required equipment or technology. Resource allocation must align with the policy’s scope and goals.

Government agencies often need to enhance their capacity to implement new policies effectively. This may involve training personnel, expanding infrastructure, or acquiring specialized expertise. Capacity building ensures that agencies have the necessary skills and tools to execute the policy competently.

Some policies require the development of regulations or rules to guide implementation. Regulatory agencies draft, review, and finalize rules that provide detailed instructions on how the policy will be enforced. Regulations clarify compliance requirements, standards, and procedures, ensuring consistency and fairness.

Transparency and communication are vital during implementation. Government agencies and policymakers keep stakeholders and the public informed about progress, milestones, and any changes. Public awareness campaigns may be employed to educate the public about the policy’s benefits and requirements.

Evaluation

The final stage, evaluation, should be aimed at assessing the effectiveness, efficiency, and impact of implemented policies. This stage serves as a feedback mechanism, providing valuable insights to policymakers and government agencies about whether the policy achieved its intended outcomes and whether any adjustments or improvements are needed. Evaluation aims to answer whether the policy accomplishes what it was designed to do. Surprising findings may emerge, such as abstinence-only sex education increasing teen pregnancy rates. Effective evaluations are systematic, and their results can inform subsequent policy decisions, creating a continuous public policy cycle.

Evaluation begins with an objective and systematic assessment of the policy’s performance. This assessment often involves the collection and analysis of data, including quantitative and qualitative indicators related to the policy’s goals and objectives. Rigorous evaluation methods ensure the reliability and validity of findings. The primary focus of policy evaluation is to measure outcomes and assess the extent to which the policy contributed to achieving its intended results. These outcomes can be social, economic, environmental, or related to public health. Evaluators analyze data to determine whether there have been positive or negative changes in these areas.

Evaluators conduct cost-benefit analyses to assess the financial implications of the policy. This involves comparing the costs incurred during policy implementation with the benefits generated. Policymakers seek to determine whether the policy’s benefits outweigh its costs and whether it represents a cost-effective solution.

For policies that involve specific programs or initiatives, programmatic evaluation is conducted. This entails assessing the performance and effectiveness of individual programs within the policy framework. It helps identify which components are working well and which may need improvement. Policymakers are attentive to unintended consequences that may have arisen as a result of the policy. These unintended consequences can be both positive and negative and may affect various aspects of society.

The perspectives and feedback of various stakeholders, including affected communities, interest groups, and experts, are essential in the evaluation process. Gathering input from those directly impacted by the policy provides valuable insights into its strengths and weaknesses. Transparent reporting of evaluation results ensures accountability in the policy process. Policymakers communicate findings to the public and stakeholders, fostering transparency and demonstrating a commitment to evidence-based decision-making.

Based on evaluation findings, recommendations for policy improvement are formulated. These recommendations may involve policy refinements, amendments, or even the development of entirely new policies based on lessons learned. The evaluation stage contributes to policy learning and knowledge generation. Policymakers and agencies use the insights gained from evaluations to make informed decisions about future policies and programmatic adjustments. Policy learning helps build a more evidence-based and adaptive policy environment. The evaluation stage is not a one-time event but rather an ongoing process. Policymakers recognize that policies may require ongoing evaluation to track long-term impacts and adapt to changing circumstances.

Multiple Streams Framework

The Multiple Streams Framework (MSF) is a prominent theory in the field of public policy that seeks to explain how policy agendas are set and decisions are made. Developed by John W. Kingdon in the 1980s, this framework provides a valuable lens through which to understand the complex and often non-linear nature of the policy process.

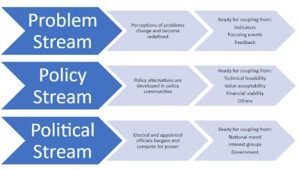

The MSF posits that the policy process involves three separate streams: the problem stream, the policy stream, and the political stream (Fig 5.2). These streams operate relatively independently but intersect at certain points, creating policy windows during which policies have a higher likelihood of being adopted. Let’s explore each of these streams in detail:

The Problem Stream: This stream represents the recognition and definition of policy issues as problems that require governmental attention. Problems can emerge from various sources, including research findings, public outcry, or crises. However, not all problems make it onto the policy agenda. According to Kingdon, certain factors, such as focusing events (unexpected events that attract media and public attention) and changes in public opinion, can increase the salience of a problem and push it closer to the agenda-setting stage.

The Policy Stream: The policy stream comprises proposed solutions to problems. Policy alternatives are developed by various actors, including experts, advocacy groups, and government agencies. These alternatives can exist independently of the problem stream and are often influenced by prior research and analysis. In the MSF, the policy stream is considered separate from the problem stream until they converge during policy windows. It is during these windows that policy entrepreneurs, individuals or groups with the expertise and motivation to promote specific policies, can play a critical role in linking problems to solutions.

The Political Stream: The political stream represents the political climate and the context in which decisions are made. Factors such as changes in government leadership, shifts in the balance of power, and the availability of financial resources influence the policy agenda. Political actors, including elected officials, interest groups, and agencies, play a pivotal role in shaping the political stream. The alignment of the political stream with the problem and policy streams creates a policy window, facilitating the adoption of specific policies.

Policy change is more likely to occur when these three streams converge. A policy window opens when a recognized problem coincides with a viable policy solution within a supportive political context. During this window of opportunity, policy entrepreneurs can advocate for their proposed solutions, and policymakers are more receptive to change. Once the window closes, the opportunity for policy change diminishes until the next convergence of the streams.

In Kingdon’s framework, agenda setting is a pivotal aspect of the policy process, and it plays a crucial role in shaping the priorities and direction of public policies. Kingdon’s approach to agenda setting involves a comprehensive understanding of how issues gain prominence on the government’s radar and ultimately become subjects of policy consideration. Kingdon’s agenda-setting model encompasses several key principles and strategies that influence policy formulation and decision-making.

- Understanding Policy Agenda Setting: Kingdon’s approach acknowledges that not all issues can become part of the government’s policy agenda. Instead, it emphasizes that agenda setting is a selective and competitive process, where various issues vie for attention and action. Kingdon recognizes that policymakers face a multitude of competing demands, limited resources, and political constraints, making it essential to strategically prioritize the issues they address.

- The Role of Issue Framing: Kingdon’s agenda-setting model emphasizes the power of issue framing. How an issue is framed can significantly impact whether it gains traction on the policy agenda. Effective framing involves presenting an issue in a compelling and persuasive manner that resonates with policymakers and the public. It highlights the urgency, relevance, and potential solutions associated with the issue, making it more likely to be considered for policy action.

- Policy Entrepreneurs: Kingdon recognizes the role of policy entrepreneurs in driving agenda setting. Policy entrepreneurs are individuals or groups that actively promote specific issues and work to place them on the policy agenda. They engage in advocacy, coalition-building, and information dissemination to raise awareness and generate support for their causes. Kingdon’s model suggests that the actions of policy entrepreneurs can significantly influence which issues rise to prominence.

- Issue Linkage and Policy Windows: Kingdon’s agenda-setting framework highlights the concept of issue linkage and the notion of policy windows. Issue linkage involves connecting a current problem or crisis to a broader policy agenda item. By linking an emerging issue to an existing policy agenda, policymakers can gain momentum and support for addressing it. Policy windows represent opportune moments when conditions align favorably for specific issues to move forward. Kingdon’s model suggests that recognizing and capitalizing on these policy windows can be instrumental in advancing certain issues.

Kingston’s theory is a valuable framework for understanding how specific issues or policy proposals can gain traction on the government’s policy agenda. Policy windows represent critical moments in the policymaking process when the conditions are ripe for a particular issue or proposal to move forward. These windows are often characterized by a convergence of factors that create a favorable environment for policy change. Some of these factors include political events, changes in public opinion, crisis situations, and shifts in the balance of power.

Within the context of Kingdon’s theory, policy entrepreneurs play a significant role in recognizing and capitalizing on these policy windows. These individuals or groups actively promote specific policy ideas and work to align them with the prevailing political climate. They seize opportunities presented by policy windows to advance their proposals and garner support from key stakeholders. Policy entrepreneurs often engage in strategic advocacy, coalition-building, and information dissemination to increase the chances of their ideas being incorporated into the policy agenda. By understanding the dynamics of policy windows and the influential role of policy entrepreneurs, policymakers can enhance their ability to navigate the complex terrain of agenda-setting and policy change effectively. Recognizing when policy windows are open and strategically leveraging them can lead to the successful adoption of policies that address pressing societal challenges.

Punctuated Equilibrium

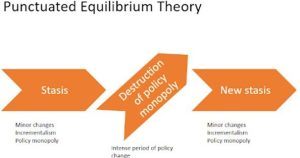

Punctuated equilibrium theory, originally developed by Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones in the field of public policy, offers a unique perspective on how policy change occurs over time. This theory challenges the traditional notion of incremental and continuous policy evolution by suggesting that public policies often experience long periods of stability or equilibrium, punctuated by brief periods of rapid and significant change.

At the core of punctuated equilibrium theory is the idea that most policies remain relatively stable and unchanged for extended periods, despite shifting societal conditions and pressures. During these periods of equilibrium, policies are characterized by a status quo bias, where stakeholders and institutions resist substantial alterations. This stability is often attributed to various factors, including the power of interest groups, institutional inertia, and the complexity of policy issues.

However, punctuated equilibrium theory posits that, occasionally, external shocks or events disrupt this equilibrium and create policy windows—brief periods when policymakers and the public are more open to considering policy change (Fig. 5.3). These policy windows can be triggered by crises, changes in government leadership, shifts in public opinion, or other exogenous factors. When a policy window opens, it creates an opportunity for policy entrepreneurs—individuals or groups with a vested interest in policy change—to advance their proposed solutions and challenge the existing policy framework.

During these windows of opportunity, policy change can occur rapidly and dramatically. New policies or significant amendments to existing ones may be adopted, altering the policy landscape in response to the external shock or event. Once the policy window closes, policies often revert to a state of equilibrium, resisting further substantive change until the next external disruption.

Punctuated equilibrium theory offers several valuable insights into public policy dynamics. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the role of external events and shocks in driving policy change, rather than relying solely on incremental adjustments. Policymakers and advocates should be attuned to the existence of policy windows and strategically position themselves to capitalize on these moments of opportunity. Additionally, this theory underscores the need for adaptability and responsiveness in policymaking, as policies can remain stable for extended periods before undergoing rapid transformations in response to changing circumstances.

Overall, punctuated equilibrium theory provides a nuanced perspective on the complexities of policy change and offers a framework for understanding the dynamics of stability and disruption in the policy process.

Advocacy Coalition Framework

The Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) is a widely recognized theoretical framework in the field of public policy that provides insights into the dynamics of policy change and the role of competing advocacy coalitions in shaping policy outcomes. Developed by Paul A. Sabatier and Hank C. Jenkins-Smith in the 1980s, the ACF offers a comprehensive understanding of how policy subsystems operate and evolve.

The core premise of the ACF is that policy processes are complex and often involve multiple actors with diverse interests and beliefs. These actors form advocacy coalitions, which are groups of individuals, organizations, and stakeholders who share common policy goals and preferences. Within each policy subsystem, there are typically multiple competing advocacy coalitions, each seeking to influence the policy agenda and design according to their beliefs and interests.

Key elements of the Advocacy Coalition Framework include:

- Belief Systems: Advocacy coalitions are driven by underlying belief systems, which encompass the deeply held values, ideologies, and policy preferences of coalition members. These belief systems shape their positions on specific policy issues. The ACF recognizes that individuals’ beliefs often guide their policy choices more than pure rationality or objective analysis.

- Policy Learning: The ACF acknowledges the role of policy learning in the policy process. As policy actors engage in debates and gather evidence, they may modify their beliefs and strategies. Policy learning can lead to coalitions adapting their positions or forming new alliances as they gain insights into the effectiveness of different policy approaches.

- Policy Subsystems: The framework distinguishes between different policy subsystems, each focused on a specific issue or set of related issues. Within these subsystems, advocacy coalitions compete for influence and attempt to shape policy outcomes. Policymakers may belong to multiple subsystems, and the interactions between them can be complex.

- External Events: External events, such as economic crises, technological advancements, or changes in public opinion, can disrupt the policy process and create opportunities or challenges for advocacy coalitions. These events can shift the balance of power and influence within a policy subsystem.

- Policy Change: Policy change, according to the ACF, is often incremental and influenced by the relative strength and stability of competing advocacy coalitions. Major policy shifts are less common and usually require significant changes in external conditions or belief systems.

Overall, the Advocacy Coalition Framework offers a nuanced perspective on policy dynamics, emphasizing the importance of belief systems, policy learning, and the role of advocacy coalitions in shaping policy outcomes. It recognizes that policy processes are not linear but rather characterized by ongoing interactions, negotiations, and adaptations among diverse stakeholders. Researchers and policymakers alike find value in this framework for understanding the complexities of policymaking and the factors that drive policy change.

Policy Feedback Theory

Policy feedback theory is a concept within the realm of public policy that explores the dynamic relationships between existing policies and the individuals or groups they affect. It posits that policies not only have direct and immediate impacts but also shape the preferences, behaviors, and interests of those subject to them, which can, in turn, influence future policy decisions.

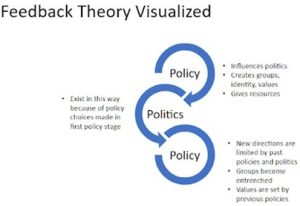

One of the primary ideas behind this theory is that policies can create feedback effects, which alter the conditions or context within which they operate. These effects can be either reinforcing or inhibiting. Reinforcing feedback loops occur when policies amplify their initial impacts, further advantaging certain groups or reinforcing a particular policy direction (Fig. 5.4). Inhibiting feedback loops, on the other hand, can limit or counteract a policy’s intended effects.

Policies also leave behind legacies that persist beyond their initial implementation. These legacies can shape the political landscape by establishing interest groups, norms, and institutions that influence future policy decisions. For example, the implementation of Social Security in the United States created a powerful constituency of beneficiaries who advocate for its maintenance and expansion.

As policies are implemented and evaluated, policymakers and affected groups can learn from their experiences. This learning can lead to policy adjustments, refinements, or reversals in response to changing circumstances or new information. Policy feedback theory highlights the role of learning in policy evolution. We saw this happen with the Affordable care Act. One provision of the ACA had been the employer mandate, requiring certain large employers to offer health insurance coverage to their employees or face penalties. The provision ended up being delayed and adjusted multiple times in response to concerns from businesses.

Policies can stimulate interest group mobilization, as individuals or organizations affected by a policy may organize to advocate for their interests. These interest groups can exert pressure on policymakers, influencing the trajectory of future policies. The ACA is also a good example of this, as the inclusion of a birth control mandate, where insurance plans were required to cover FDA-approved contraceptive methods and related services without cost-sharing for women. This provision mobilized a number of religious-based individuals and organizations who argued that the mandate was a violation of their religious liberty. The legal challenges led by these groups went all the way to the Supreme Court where in the landmark case Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014), the Court ruled that certain closely-held for-profit corporations with religious objections could be exempted from the mandate.

Policy feedback theory recognizes that past policy decisions can constrain future choices, creating a path-dependent policy trajectory. Once certain policies are in place, they can limit the feasibility of alternative policy options. This path dependence can be both a source of stability and an obstacle to policy change.

Policy feedback theory offers a valuable lens through which to examine the intricate relationships between policies, the individuals or groups they affect, and the broader policy landscape. It underscores the long-term consequences of policy decisions, the role of interest groups and advocacy, and the potential for policies to shape future policy directions. By understanding how policies create feedback loops and legacies, policymakers can make more informed decisions and anticipate the broader implications of their choices.

Summary

Public administration serves as an instrumental component of policy implementation, operating within the constraints of republican government institutions. These limitations are inherent, stemming from the leader’s philosophical perspective on exercising power and the legal boundaries imposed by constitutional checks and balances.

This chapter explores the key concepts, theories, and processes that shape the development, implementation, and evaluation of public policies. The chapter begins by defining public policy and highlighting its significance in modern governance, emphasizing its role in addressing societal issues and achieving public goals.

The chapter delves into the policy cycle, offering a step-by-step examination of how policies are formulated, adopted, implemented, and assessed. It discusses the various stages of the policy process, from problem identification and agenda setting to policy design, implementation strategies, and policy evaluation. Throughout this exploration, the chapter underscores the dynamic and iterative nature of policy development.

The text also covers the major actors and institutions involved in public policy, including government agencies, legislatures, executive branches, interest groups, and the role of citizens and the media. It discusses the interactions and power dynamics among these actors, highlighting how they influence policy outcomes.

Key policy theories are introduced and examined in the chapter, providing students with a foundation for understanding the analytical frameworks that underpin policy analysis and decision-making. These theories include the rational choice model, incrementalism, pluralism, and the policy subsystem approach, among others.

Bibliography

Bush, George (2001) “Statement on Signing the Authorization for Use of Military Force” Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents, September 21, p. 1319.

Cartwright, Nancy and Jeremy Hardie (2012) Evidence-Based Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clausewitz, Karl von (1832) On War. New York: Penguin Press.

Dahl, Robert A. and Charles E. Lindblom (1953) Politics, Economics, and Welfare. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Downs, Anthony (1972) “Up and Down with Ecology—The Issue-Attention Cycle.” Public Interest 28 (summer).

EPA History. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). https://www.epa.gov/history

Etzioni, Amitai (1967) “Mixed Scanning: A ‘Third’ Approach to Decision Making,” Public Administration Review (December).

Kingdon, John W. (1995) Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Lasswell, Harold D. (1936). Politics: Who Gets What, When, How. New York: Smith.

Lindblom, Charles E. (1959) “The Science of Muddling Through.” Public Administration Review (spring).

Lipsky, Michael (1980) Street-Level Bureaucracy. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lowi, Theodore, J. (1979) The End of Liberalism, 2nd ed. New York: Norton.

Rothman, L. (2017, March 22). Environmental protection agency: Why the EPA was created. Time. https://time.com/4696104/environmental-protection-agency-1970-history/

Simon, Herbert A. (1997) Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organizations, 4th ed. New York: Macmillan.

Smith, K. B. (2018). The Public Policy Theory Primer. Routledge, an imprint of Taylor and Francis.

Social Security History. (n.d.). https://www.ssa.gov/history/50ed.html#:~:text=Roosevelt%20signed%20the%20Social%20Securi ty,work%20begun%20by%20the%20Committee

Stone, Deborah (2012) Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Wilson, James Q. (1968) Varieties of Police Behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Media Attributions

- Pollution © Marc St. Gil, Environmental Protection Agency is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Social Security Poster of a Mother and Her Child © National Archives and Records Administration is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Road sign © INKIE is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Unemployment breadline is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 5.1

- Figure 5.2

- Figure 5.3

- Figure 5.4