Chapter 3: Organizational Management and the Foundations of Administration

We can define public administration as the “management of government programs.” In the United States we often reference Woodrow Wilson as the starting point for the establishment of an independent field in Public Administration. Occasionally, there is also mention of the roots of the practice of public administration, and a reference to the Greek and Roman civilizations. If we are a little more expansive in our conceptualization of the field, though, there are many other examples from around the world and in different time periods that we can use in our understanding of public administration.

Public Administration in Ancient Egypt

The Ancient Egyptian civilization and state continued over more than 3 millennia from 3100-343 BC. The term state, although sometimes reserved for more modern entities in Europe, was perceived by others to be well established during the Ancient Egyptian times. The main statehood elements were there, including: a clearly marked territory, an administrative apparatus and a population abiding to authority.

A simplified description of the government structure in Ancient Egyptian times marks it as resembling a pyramid. The King/Pharaoh was positioned at the top of the pyramid, held supreme power and his words were considered law. He held ownership of the land and all material resources of the country at large and was the supreme military commander. Beneath the King was the visier, the word now used in Arabic to refer to a minister, but during Ancient Egyptian times it referred to the Prime Minister equivalent. The visier played various roles. He was the King’s Chief Architect, was responsible for all the administration affairs and was also the chief justice. Additionally, on the same level as the visier, there was the High Priest. Middle level officials were responsible for a wide array of functions, including agriculture, the granaries, the treasury, trade, public works and the army. Next, lower level officials were responsible for dealing directly with craftsmen, farmers and soldiers. The country was divided into 42 regions, referred to as nomes, each headed by a nomarch who reported to the visier.

During the Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt (2050-1780 BC), there are reports of a very sophisticated system for workers’ management, including keeping rosters of names, developing work targets, regularly checking and monitoring performance and paying out wages.

Ancient Egypt had a well-developed education system catering to the development of civil servants so as to prepare them for the jobs they were going to occupy in government. The education given to the future civil servants was described as catering to teaching them the technical aspects of state management plus developing their overall intellectual abilities.

Public Administration in Ancient China

Meanwhile, the timeline of the Ancient Chinese civilization dates back to 1766 BC to 220 AD, with the Western Han Empire (206 BC – 23 AD) being one of the most prominent and recognized bureaucratic empires. It is reported that under the Han empire there were around 60 million people under its control and 120 thousand government officials serving them. The emperor was the head of the Han empire and was aided by the bureaucracy to manage the country. The emperor was the source of authority. The government administration was headed by a chancellor to whom thirteen bureaus reported with titles including: memorials, communication, military transportation, gold, criminal executions and granaries. A well-developed system of recruiting, promoting and annual auditing of government officials was in place.

The Great Wall of China, one of the most iconic and enduring architectural marvels in human history, stands as a remarkable feat of public administration. Constructed over centuries and spanning thousands of miles, this colossal defensive structure is not only a testament to the engineering prowess of ancient China but also a striking example of effective governance, strategic planning, and collaborative effort.

The Great Wall of China’s construction can be traced back to multiple dynasties, with its origins dating as far back as the 7th century BC. Its primary purpose was defense, serving as a formidable barrier against invasions by nomadic tribes from the north. This vision for national security required long-term planning and a clear understanding of the strategic value of such a structure.

Around 220 B.C., China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang of the Qin Dynasty, launched a monumental initiative that would resonate through the ages – the construction of the Great Wall of China. This ambitious endeavor aimed to unite and extend existing fortifications, creating a singular, awe-inspiring barrier spanning over 3,000 miles to safeguard against northern threats. General Meng Tian spearheaded this colossal undertaking, mobilizing a workforce comprising soldiers, convicts, and common laborers. Constructed primarily from earth and stone, the wall rose to heights of 15 to 30 feet, adorned with sentinel guard towers and strategically overlapping segments for enhanced defense. Over centuries, various dynasties undertook repairs, extensions, and renovations, with the Ming Dynasty’s (1368-1644) rendition standing as the most iconic, constructed as a defensive precaution. Today, the Great Wall of China remains a global marvel, emblematic not only of China’s historical might but also of meticulous coordination and foresight through visionary leadership, centralized authority, resource allocation, strategic planning, and unwavering commitment to long-term preservation –an enduring testament to humanity’s capacity for remarkable achievements through collective effort and visionary perseverance.

The Great Wall’s enduring presence symbolizes a monumental triumph in the realm of public administration. It necessitated the confluence of vision, centralized authority, resource mobilization, labor force management, strategic planning, and ongoing maintenance. Its historical significance, immense scale, and unique architectural style continue to captivate the world. Erected by a diverse workforce of soldiers, prisoners, and local laborers, the wall reflects the wisdom and determination of the Chinese people. In an era when weaponry was limited to swords, spears, lances, and bows, fortifications with passes, watchtowers, signal towers, and moats became essential for defense. Emperors, notably Emperor Qin Shihuang, refined the wall’s design to safeguard northern China against the Huns and establish a defensive tradition for future dynasties. The Great Wall of China serves as an enduring testament to the power of coordinated effort and long-term planning, showcasing governments’ and societies’ ability to undertake ambitious and enduring projects through effective public administration, even in ancient times.

Origins of Organizational Management

In a 2013 interview with Rolling Stone magazine, American musician, singer and songwriter Mike Love, who is best known as a founding member of the Beach Boys was asked about his thoughts on the legacy of the band and their music. Love responded by saying that, “the history of mankind is the history of war.” Whether man is so naturally predisposed to war is hotly debated, however civilization, administration and the military have always been intertwined. The vocabulary of public administration is heavily influenced by military origins, with core concepts in modern strategic thought anticipated by historic military strategists like Sun-Tzu in China and Napoleon Bonaparte in France.The field of public administration owes much to military strategy and administration, with hierarchy, line and staff personnel, logistics and communications all developed by armies long ago. Even the word strategy itself comes from the ancient Greek meaning “the art of the general.”

Long ago, before it was common to have universities where one could go and learn the art and science of administration, the rise of an officer class allowed societies to extend beyond the household. Military service was really the only place where one could learn how to manage large groups of people and engage them in task completion, hence military officers were the first public administrators. Walls built for defense, troops gathered for battle, food procured for the front lines…these were the first public projects.

The Military

Throughout history, civilization and administration have been tightly intertwined. Cities, in ancient times, were defined by their walls. As primitive tribes settled in cities and transitioned to civilization, they needed to be organized for defense, necessitating a sophisticated administrative system. The emergence of cities without walls became possible only recently, thanks to state authorities capable of maintaining peace across large regions. This marked the birth and evolution of the management profession, closely tied to military matters. The quote “The history of the world is the history of warfare” is often attributed to the British historian Sir Walter Raleigh. However, it’s worth noting that the exact wording and origin of this statement may vary, and similar sentiments about the centrality of conflict in history have been expressed by various scholars and historians throughout time.The world’s history is, in many ways, a history of warfare, and war on a state level is inconceivable without an effective system of public administration backing it.

The earliest public administrators were military officers, and the development of societies beyond extended families hinged on the rise of an officer class. The first armies were essentially groups with managers, evolving over time as these managers acquired the organizational skills needed to lead large groups and govern expansive territories. These early military skills form the fundamental building blocks of administrative processes, encompassing concepts like hierarchy, personnel, logistics, and strategy. Even the concept of reform can trace its origins to the military, signifying the reorganization of ranks for another offensive, whether against another army or a complex management issue.

Public administration has borrowed a significant number of words and concepts from the military, reflecting the historical connection between the two fields. These borrowed terms often serve as analogies to describe organizational structures, processes, and strategies. Here are some common examples:

- Hierarchy: Refers to the structured levels of authority and responsibility within an organization, much like the military chain of command.

- Chain of Command: Describes the hierarchical structure of decision-making and reporting within an organization.

- Commander: In public administration, this term is used to denote a leader or manager responsible for a specific area or unit.

- Mission: Similar to military missions, it refers to the specific goals or objectives an organization seeks to achieve.

- Strategic Planning: Draws from military strategy and involves setting long-term goals and determining the best approach to achieve them.

- Tactics: In the context of public administration, tactics involve specific actions taken to implement strategies and achieve objectives.

- Logistics: Refers to the management of resources, materials, and supplies needed for the operation of an organization.

- Deployment: Often used in emergency management or disaster response to describe the allocation and positioning of personnel and resources.

- Operations: Like military operations, this term describes the coordinated activities and actions undertaken to achieve specific goals.

- Intelligence: In public administration, intelligence refers to the gathering and analysis of information to inform decision-making, as seen in intelligence agencies.

- Briefing: A structured presentation of information, much like military briefings, used to inform decision-makers.

- Mobilization: Refers to the process of preparing and organizing resources and personnel for a specific task or mission.

- Command Center: A central location where decision-making and coordination of activities take place, similar to military command centers.

- Strategy Session: A meeting or discussion focused on long-term planning and decision-making, inspired by military strategy meetings.

- Frontline: Describes employees or personnel who directly interact with the public or clients, similar to soldiers on the frontlines.

- Campaign: Often used in political administration, this term is borrowed from military campaigns and refers to organized efforts to achieve a specific goal or objective.

- Drill: Refers to training exercises or practices that help prepare personnel for specific tasks, similar to military drills.

- Rules of Engagement: May be used to define the guidelines or procedures for interacting with the public, clients, or other organizations.

We can define public administration as the “management of government programs.” In the United States we often reference Woodrow Wilson as the starting point for the establishment of an independent field in Public Administration. Occasionally, there is also mention of the roots of the practice of public administration, and a reference to the Greek and Roman civilizations. If we are a little more expansive in our conceptualization of the field, though, there are many other examples from around the world and in different time periods that we can use in our understanding of public administration.

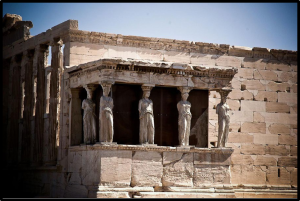

Ancient Greece

The ancient Greeks made significant contributions to the development of public administration, laying the groundwork for many of the administrative concepts and practices we recognize today. Their political, philosophical, and organizational ideas continue to influence modern governance and public administration in various ways.

- Democracy: The concept of democracy, which originated in Athens in the 5th century BCE, is one of the most prominent Greek contributions to public administration. Athenian democracy emphasized citizen participation in decision-making, including direct involvement in policy formulation and voting. This notion of citizen engagement in governance profoundly influenced the development of democratic governments worldwide, where public administrators work to ensure transparency, accountability, and participation.

- Written Laws: The Greeks, particularly in Athens, were among the first to establish written laws. The law code of Draco in the 7th century BCE and later the reforms of Solon set legal precedents that emphasized the importance of written laws as a basis for justice. This practice laid the foundation for the codification of laws in many modern legal systems, promoting transparency and fairness in public administration.

- Citizenship and Polis: The Greeks developed the concept of citizenship, wherein individuals had specific rights and responsibilities within their city-states, or polis. Citizenship conferred both privileges and duties, influencing the idea of civic engagement and the relationship between individuals and the state. This concept has resonated in modern times, shaping the relationship between citizens and their governments.

- Philosophical Foundations: Greek philosophers, such as Plato and Aristotle, contributed profoundly to the intellectual underpinnings of public administration. Plato’s “Republic” and Aristotle’s “Politics” explored the organization and function of the state, political ethics, and the role of administrators in achieving the common good. Their writings continue to inform discussions on governance, ethics, and the responsibilities of public administrators.

- Ostracism: The practice of ostracism, where citizens could vote to banish a potentially disruptive individual from the city for a specified period, reflects early attempts to maintain social order. This concept has parallels in modern administrative processes for managing disruptive or unethical behavior within organizations.

- Jury System: The Greeks introduced the concept of trial by jury, where citizens served as jurors to determine the outcome of legal cases. This practice influenced the development of modern judicial systems, emphasizing impartiality, fairness, and community participation in the administration of justice.

- Public Spaces and Infrastructure: Greek city-states invested in the construction of public spaces, including marketplaces (agoras), temples, and theaters. The management and maintenance of such public infrastructure required administrative oversight and influenced subsequent urban planning and public works projects.

- Rhetoric and Communication: The Greeks emphasized the art of persuasion and effective communication, which are essential skills for public administrators. Rhetoric, as taught by figures like Aristotle, became central to the ability to convey ideas and policies effectively to the public and decision-makers.

- Education and Academia: The Greeks valued education and established academies like Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum. These institutions laid the groundwork for higher education and the training of future leaders and administrators, contributing to the professionalization of public administration.

The enduring legacy of Greek influence on public administration is evident in the principles of democracy, the rule of law, citzen engagement, ethical governance, and administrative transparency that continue to guide modern governments and organizations. Greek political thought and organizational concepts remain foundational elements of contemporary public administration, reflecting their enduring relevance in the field.

Ancient Rome

The Roman Empire, known for its remarkable governance and administrative systems, has had a profound and lasting influence on public administration. The principles and practices developed during the height of the Roman Empire continue to shape modern government and administrative processes around the world.

- Legal System: Roman law, particularly the Corpus Juris Civilis, commonly known as the Justinian Code, laid the foundation for modern legal systems in many parts of the world. It introduced concepts such as due process, legal equality, and property rights, which remain fundamental to contemporary legal frameworks. The Roman legal system emphasized the importance of written laws, codification, and the rule of law, all of which are central to modern public administration.

- Bureaucracy: The Roman Empire established an extensive bureaucracy to manage its vast territories efficiently. This bureaucracy included various administrative positions, from provincial governors (proconsuls) to tax collectors (publicans). These administrative roles and structures served as a model for subsequent governments, including the Byzantine Empire and medieval European states. The concept of a professional civil service was rooted in Roman administrative practices.

- Local Governance: Roman governance was characterized by a decentralized administrative system that delegated authority to local officials. Cities and provinces had their own magistrates and councils responsible for local administration and public works. This system of local governance influenced the development of municipal governments in later periods, contributing to the emergence of modern local government structures.

- Census and Taxation: The Romans conducted regular censuses to assess the population and property for taxation purposes. The careful collection of demographic and economic data and the fair assessment of taxes laid the groundwork for modern tax administration and the principles of equitable taxation.

- Infrastructure and Public Works: The Roman Empire was renowned for its extensive network of roads, aqueducts, bridges, and other public infrastructure. The construction, maintenance, and management of such public works required efficient administrative oversight, including budgeting, planning, and resource allocation. These practices provided a model for subsequent governments in managing critical infrastructure projects.

- Citizenship and Rights: Roman citizenship, with its associated rights and responsibilities, was a key element of Roman administration. Citizenship conveyed certain privileges, including the right to vote and participate in government. The concept of citizenship and the protection of individual rights influenced the development of democratic societies and the protection of civil liberties in modern public administration.

- Military Administration: The Roman military was highly organized and disciplined, with a well-structured chain of command. Military administration principles, including logistics, supply chains, and strategic planning, have been adopted and adapted by modern armed forces and have influenced contemporary defense and security administration.

- Record Keeping: Romans were meticulous record keepers, documenting various aspects of administration, including land ownership, legal contracts, and financial transactions. The practice of maintaining records and archives influenced the development of modern record-keeping systems and administrative transparency.

The Roman influence on public administration is profound and enduring. The principles of Roman law, governance structures, local administration, infrastructure management, taxation, citizenship, military organization, and record keeping have left an indelible mark on administrative practices and systems across the globe. The lessons learned from Roman administration continue to shape the way governments and organizations manage their affairs, providing a timeless legacy of effective and efficient public administration.

Organization Theory

Organization theory is a multidisciplinary field of study that examines the structure, behavior, and functioning of organizations. It seeks to understand the complex dynamics within these entities, ranging from small businesses and nonprofit organizations to large corporations and government agencies. Organization theory draws from various disciplines, including sociology, psychology, economics, and management, to develop frameworks and models that explain how organizations operate and adapt to their environments.

At its core, organization theory explores several key questions:

1. How do organizations form and evolve?

-

- Organization theory delves into the processes by which organizations are established and how they change over time. It examines factors such as leadership, decision-making, and external influences that shape an organization’s trajectory.

2. What are the structures and designs of organizations?

-

- This aspect of organization theory investigates the formal and informal structures that define how work is organized within an organization. It includes discussions on hierarchy, division of labor, reporting relationships, and coordination mechanisms.

3. How do organizations function internally?

-

- Understanding the inner workings of organizations is a fundamental concern of organization theory. This includes examining how communication flows, how decisions are made, and how conflicts are resolved within the organizational context.

4. How do organizations interact with their external environment?

-

- Organizations don’t exist in isolation; they interact with their environments, which include competitors, regulators, customers, and other stakeholders. Organization theory explores how organizations adapt to external pressures and opportunities.

5. What motivates individuals within organizations?

-

- The behavior of individuals within organizations is a critical aspect of organization theory. It considers issues related to motivation, job satisfaction, leadership, and organizational culture.

6. How do organizations achieve their goals?

-

- This question focuses on the strategies and processes organizations employ to attain their objectives. It encompasses aspects of performance measurement, goal-setting, and resource allocation.

7. How do organizations respond to change?

-

- In a rapidly evolving world, organizations must adapt to new challenges and opportunities. Organization theory explores how organizations manage change, innovate, and remain resilient.

Organization theory has evolved over time, with various schools of thought and perspectives emerging. Some prominent approaches within organization theory include:

- Classical Theory

- Neoclassical Theory

- Contingency Theory

- Structural Theory

- Systems Theory

Organization theory is a dynamic and evolving field, continually adapting to changes in the business environment, technological advancements, and shifts in societal values. It plays a crucial role in informing organizational leaders, policymakers, and researchers, offering insights into how to design, manage, and lead effective organizations in a complex and interconnected world. Understanding organization theory is essential for anyone interested in the dynamics of modern institutions and their impact on individuals, communities, and society as a whole.

Classical Organization Theory

Though organizations have been operating for a much longer time, the study of organizations has really only been a thing since the late 1800s. Classical organization theory serves as the foundational framework upon which other theories of organization

have been constructed. The core principles and assumptions of classical organization theory, originally rooted in the industrial revolution and the fields of engineering, and economics, have remained largely unaltered. An understanding of classical organization theory is crucial, not only due to its historical significance but, more significantly, because all other analyses and theories presuppose familiarity with its concepts.

The fundamental tenets of organization theory can be succinctly summarized as follows:

- Organizations exist to achieve production-related and economic objectives.

- There exists an optimal method of organizing for production, which can be ascertained through systematic, scientific inquiry.

- The highest level of production efficiency is achieved through specialization and the division of labor.

- Individuals and organizations behave in accordance with rational economic principles.

It is vital to contextualize the evolution of any theory. The beliefs held by early management theorists regarding the functioning and ideal functioning of organizations directly mirrored the societal values of their respective eras, which were often harsh. It was not until well into the twentieth century that industrial workers in the United States and Europe began to attain even limited “rights” as members of organizations. During this period, workers were not perceived as unique individuals but rather as interchangeable “cogs in a machine.”

The emergence of power-driven machinery and, consequently, the modern factory system gave rise to our contemporary notions of economic organizations and organizations designed for production. Under the factory system, the triumph of organizations was predicated on well-structured production systems capable of keeping machines in continuous operation and cost containment. Industrial and mechanical engineers, along with their machinery, emerged as the linchpins of production. Organizational structures and production systems were designed to maximize the utility of these machines. Organizations were envisioned to operate analogously to machines, with individuals, capital, and machinery serving as their constituent components. Analogous to how industrial engineers aimed to create “optimal” machines to maintain factory productivity, theories on the “optimal approach” to organizing for production were largely dominated by the thought processes reminiscent of industrial and mechanical engineering.

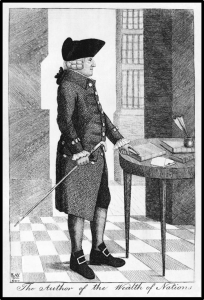

Adam Smith and the Division of Labor

Adam Smith, a Scottish economist from the 18th century, raised concerns related to centralization of equipment and labor in factories, specialized division of labor, the management of this specialization, and the economic benefits derived from factory equipment. In his influential work, “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,” Smith discussed the optimal organization of a pin factory, using it as an illustrative example. This focus on specialization of labor was pivotal to Smith’s concept of the “invisible hand” in economics, where the most efficient participants in a competitive market would reap the greatest rewards.

Traditional pin makers could produce only a few dozen pins each day. However, when these individuals were organized within a factory, each worker performed a specific, limited operation, leading to the production of tens of thousands of pins daily. Smith’s chapter on the division of labor, appearing during the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, is one of the most renowned and influential statements regarding the economic rationale behind the factory system, despite the existence of factory systems in ancient times, as described by Xenophon in 370 BC.

The year 1776 is traditionally considered the starting point of organization theory as an applied science and academic discipline, primarily due to the popularity and impact of Smith’s 1776 book. This year also marks a significant milestone in various other historical events.

Formal organizations, whether 18th-century factories or contemporary corporations, function as force multipliers, amplifying the collective efforts of individuals beyond the sum of their individual capacities. Smith’s example of pin makers illustrates this concept: individually, they could produce only a few dozen pins a day, but as a coordinated team, they could manufacture many thousands. The military employs the term “force multiplier” to describe technologies that enhance a soldier’s effectiveness on the battlefield. For instance, a machine gun is a force multiplier because one soldier with it can be as effective as a hundred soldiers armed with traditional rifles. Similarly, modern computers and word processors serve as force multipliers in civilian contexts, as one operator can achieve the productivity of multiple traditional typists. Smith’s insights emphasize that effective organization, akin to technology, is a potent force multiplier in its own right and can significantly enhance productivity, all while being more cost-effective.

Scientific Management

The traditional hierarchical organizational structure faced challenges during periods of instability, such as the French Revolution, the Age of Napoléon, and the industrial revolution. It relied on well-trained military officers and factory supervisors, which worked well under stable conditions. However, these individuals struggled to adapt to revolutionary circumstances and increased competition. To address this, organizations introduced a major structural innovation of the era: the staff concept.

The staff concept aimed to overcome the limitations of relying solely on the intellectual capacity of top leaders. It encompassed two interconnected ideas: the use of assistants, such as secretaries and clerks, followed by the staff principle or concept. The latter involved creating a specific organizational unit responsible for thinking, planning, innovating, and implementing ideas. This shift became crucial in managing the complex and differentiated functions of organizations.

During the industrial revolution, the success of businesses hinged on well-organized production systems that optimized machine utilization and controlled costs. Industrial and mechanical engineers played a pivotal role in this process. Organizational structures and production systems needed constant refinement to leverage evolving technology effectively. The prevailing belief was that organizations should function akin to machines, with individuals serving as integral components. This engineering-oriented thinking heavily influenced theories on how to organize people efficiently within the industrial machine.

The staff concept, originating from the Prussian military reforms, significantly impacted both the public and private sectors. It can be traced back to ancient Greek armies and gained prominence through the Prussian military’s transformation into a highly efficient force by the mid-19th century. The Prussian general staff comprised intellectually capable officers selected early in their careers, dedicating their professional lives to central planning. They developed strategies and tactics, eventually becoming a model adopted by major military powers worldwide.

Modified versions of the general staff concept found their way into burgeoning industrial and governmental organizations. In the late 19th century, American industrial engineers advocated for scientific work design to enhance worker productivity. These engineers essentially played the civilian role analogous to the military general staff. They conducted research and planning to improve organizational competitiveness compared to others.

Scientific management emerged from engineering principles, with a notable connection to the teachings of Jomini. Many 19th-century American engineers, whether educated at West Point or not, had familiarity with sound principles. The influence of West Point, where Jomini’s ideas were taught, extended to the engineers who built critical infrastructure, such as railroads, canals, harbors, and bridges. The rise of scientific management was exemplified by Henry R. Towne’s presentation on “The Engineer as an Economist” at the 1886 meeting of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. These engineers, whether formally educated or not, recognized the value of sound principles in their work.

Frederick Taylor and Scientific Management: Revolutionizing the Workplace

Frederick Winslow Taylor, widely regarded as the “father of scientific management,” made profound contributions to industrial engineering during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His innovative principles of scientific management, which aimed to optimize productivity, efficiency, and worker performance, have significantly impacted modern workplaces. Taylor’s core belief was that organizations should function like well- oiled machines, and he introduced several groundbreaking principles and practices to revolutionize work processes.

At the heart of Taylor’s philosophy was the concept of scientific task analysis. He advocated for the meticulous examination of every task within an organization, breaking them down into smaller, manageable components, and identifying the most efficient methods for each component. Standardization played a pivotal role in his approach; once the optimal method was identified through scientific analysis, it should be standardized and followed uniformly by all workers. Taylor also stressed the importance of selecting and training workers based on their abilities, as well as introducing incentive systems to motivate employees to exceed established standards. Moreover, he emphasized collaboration between workers and management, with each side having distinct responsibilities.

Taylor’s revolutionary ideas were well-suited for their time due to several contextual factors. The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the peak of the Industrial Revolution, marked by the rapid transition from traditional craftsmanship-based production to large-scale industrial manufacturing. The increased reliance on machinery and assembly-line processes necessitated more efficient management practices. Moreover, the complexity of organizations, along with the challenges posed by labor- management disputes, prompted the adoption of Taylor’s scientific management principles.

Key industries such as manufacturing, mining, and steel production were transitioning to mass production methods, and Taylor’s emphasis on standardization and efficiency resonated with these sectors. The expansion of transportation networks, particularly railroads, required improved logistics, scheduling, and operational efficiency, making Taylor’s principles relevant to the transportation sector. The era was characterized by increasing global competition, particularly in manufacturing, prompting businesses to seek cost-saving and efficiency-enhancing strategies. Concurrent technological advancements, particularly in timekeeping and measurement tools, facilitated accurate data collection and analysis, which were critical for implementing scientific management principles. The establishment of management education and business schools further contributed to the dissemination and integration of Taylor’s ideas.

Frederick Taylor’s entrepreneurial drive and persuasive advocacy for his ideas played a crucial role in their widespread adoption. However, it’s essential to acknowledge that Taylor’s approach faced criticism for its focus on efficiency, which some argued led to the dehumanization of workers. Critics contended that workers felt alienated and disempowered by the rigid adherence to standardized methods and the relentless pursuit of productivity.

Nonetheless, Taylor’s impact on management theory and practice remains undeniable. His principles laid the foundation for modern management practices, including process optimization, performance measurement, and the use of incentives. Scientific management served as a precursor to subsequent management theories such as Total Quality Management (TQM), Lean Management, and Six Sigma, all of which continue to shape contemporary organizations. In conclusion, Frederick Taylor’s contributions to management through scientific management have left an enduring legacy, influencing how organizations operate and manage resources. While his ideas have evolved and adapted to changing workplace dynamics, Taylor’s fundamental principles of efficiency and productivity remain highly influential in contemporary management practices.

Henri Fayol’s Management Principles: A Pillar of Modern Management

Henri Fayol, a French mining engineer and management theorist, made significant contributions to the field of management in the early 20th century. His work laid the foundation for many of the management principles that continue to guide organizations today. Fayol’s management principles are a cornerstone of modern management theory and practice. In 1916, he published his influential book, “General and Industrial Management,” in which he outlined his principles of management.

Fayol proposed 14 principles of management that provide a framework for effective organizational management.

- Division of Labor: Fayol advocated for the division of work among employees to enhance specialization and efficiency.

- Authority and Responsibility: Managers should have the authority to give orders, but they must also assume responsibility for their decisions.

- Discipline: A well-organized workplace requires clear rules and consequences for violations.

- Unity of Command: Employees should receive orders from only one superior to avoid confusion and conflicts.

- Unity of Direction: Activities within an organization should be guided by a single plan and objective.

- Subordination of Individual Interests: The interests of individual employees should be subordinated to the interests of the organization as a whole.

- Remuneration: Fair and equitable compensation should be provided to employees for their contributions.

- Centralization: The degree of centralization in an organization should be determined by factors such as the nature of the work and the competence of employees.

- Scalar Chain: There should be a clear chain of authority and communication from the top management to the lowest levels.

- Order: Resources and employees should be organized in the most efficient manner.

- Equity: Managers should be fair and just in their dealings with employees.

- Stability of Tenure: Employee turnover should be minimized to ensure continuity and stability within the organization.

- Initiative: Employees should be encouraged to take initiative and contribute to the organization’s goals.

- Esprit de Corps: Promote a sense of unity and team spirit among employees.

Fayol’s principles of management have had a profound and lasting impact on the field of management. They continue to serve as a guide for managers and organizations seeking to improve their efficiency and effectiveness. Fayol’s emphasis on clear organizational structures, managerial authority, and principles of discipline and unity remain relevant in today’s complex business environment.

Moreover, Fayol’s work contributed to the development of management as a distinct discipline. His principles, along with the works of other early management thinkers like Frederick Taylor and Max Weber, paved the way for the systematic study and teaching of management in academic and professional settings.

The Period of Orthodoxy in Public Administration

The period of orthodoxy in public administration, often referred to as the “Traditional” or “Classical Period,” was a foundational era that significantly shaped the field of public administration. This period, which spanned roughly from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, was characterized by a set of dominant principles and practices that laid the groundwork for modern public administration.

Throughout the 20th century, the field of public administration had primarily focused on practical and normative aspects rather than developing a comprehensive theory. This pragmatic orientation contributed to the absence of a unifying theory in public administration until the mid-20th century. It was only with the dissemination of Max Weber’s theory of bureaucracy that significant interest in a theory of public administration emerged. However, much of the bureaucratic theory that followed was directed at the private sector, with limited efforts to connect organizational principles with political theory.

One of the central principles in public administration has been the pursuit of economy and efficiency, aiming to provide public services at the lowest possible cost. This focus on efficiency has been a prominent objective of administrative reform. Despite increasing concerns about other values such as responsiveness to public needs, justice, equal treatment, and citizen involvement in government decisions, efficiency remains a major goal.

Efforts to improve efficiency and effectiveness in public administration often revolved around questions of formal organization. The belief was that administrative problems could be partially resolved through reorganization. Many organizational principles were adopted, some originating from the military and others from private business. These principles included organizing departments and agencies based on common purposes, grouping similar activities in single units, aligning responsibility with authority, ensuring unity of command, limiting the number of subordinates reporting to a single supervisor, distinguishing between line and staff activities, employing management by exception, and maintaining a clear chain of command.

The classical approach to public administration, characterized by its emphasis on efficiency and formal organization, reached its peak development in the United States during the 1930s. However, this approach also gained acceptance in various countries through educational programs and international organizations. Despite its widespread adoption, some elements of the classical approach faced resistance from governments with different legal perspectives. Moreover, challenges to this approach emerged as early as the 1930s.

The orthodox doctrine of public administration assumed that administrators merely implemented policies determined by others and should remain neutral regarding values and goals. However, this perspective began to shift during the Great Depression and World War II. It became evident that administrators played a significant role in policy development, and their decisions often involved implicit value judgments. Many administrators were engaged in policy-related work, blurring the line between administration and politics.

The idea of a value-free and neutral administration was increasingly challenged, leading to a growing concern with policy formation and decision-making techniques. While the concept of neutral administration is considered untenable by many, finding a satisfactory alternative remains a challenge. Ensuring that career administrators make responsible and responsive policy decisions, while coordinating their work with politically elected or appointed officials, continues to be a crucial focus, particularly in democratic states.

Bureaucracy

Bureaucracy is a complex organizational structure characterized by intricate systems and procedures designed to ensure consistency and oversight, often resulting in slower decision-making processes. This term encompasses standardized methodologies commonly found in governmental bodies and large organizations, including private corporations, used to implement and enforce established rules and regulations.

Critics often associate bureaucracy with redundancy, arbitrariness, and inefficiency, using terms like “bureaucrat” and “bureaucratic” negatively. However, a balanced perspective acknowledges bureaucracy’s role in guiding organizations within closed systems, maintaining order and fairness through formal and inflexible processes. Hierarchical procedures are a hallmark of bureaucracy, simplifying or replacing autonomous decision-making.

“The only thing that moves slower than a government agency is the line to get there.” -A joke I heard from my bureaucrat father when I was a kid

The roots of modern Western-style bureaucracies can be traced back to Europe, where centralized autocratic regimes necessitated the delegation of authority to appointed representatives. American bureaucracy still bears traces of its European origins, making it susceptible to criticism for being “unresponsive.” Advocacy groups for “good government” argue that politicians often influence the bureaucracy to serve specific interests.

“The bureaucracy” encompasses all government officials, from top-level figures to those in less prominent roles. While the conventional image of a bureaucrat involves desk- bound tasks, many bureaucrats hold active positions like law enforcement officers, educators, and firefighters. The term bureaucracy is also used as criticism for organizations bogged down by excessive bureaucracy or red tape. While some anecdotes humorously highlight inefficiencies, it’s crucial to recognize that efficient government agencies often go unnoticed, overshadowed by negative incidents. Widespread perceptions of inefficiency have added complexity to the term bureaucracy.

Max Weber’s Bureaucracy

Max Weber’s concept of bureaucracy is a cornerstone of modern organizational theory and has significantly influenced the field of public administration. In his seminal work “Economy and Society” (1922), Weber introduced the idea of bureaucracy as a rational and effective form of organization. It is noteworthy that Weber does not say that bureaucracy is good or that he likes it. He has simply found that in all of the organizations and projects that he has studied, ones with a bureaucratic structure tend to be the most successful. His ideas have had a profound impact on how we understand and structure public and private organizations.

Weber’s definition of bureaucracy comprises several key characteristics:

- Hierarchy: Bureaucracies are organized in a clear and well-defined hierarchy, with each level having authority over the level below it. This hierarchical structure ensures that responsibilities and tasks are clearly delineated.

- Division of Labor: Within a bureaucratic organization, tasks and responsibilities are specialized and divided among individuals or units. This specialization allows for efficiency and expertise in performing specific functions.

- Formal Rules and Procedures: Bureaucracies operate based on formal rules and standardized procedures. These rules guide decision-making and ensure consistency in how tasks are performed.

- Impersonality: Bureaucracies emphasize impersonal interactions and decisions. Personal biases and favoritism should not play a role in bureaucratic processes. Decisions are made based on established rules and regulations.

- Merit-Based Selection: Recruitment and promotion within a bureaucracy should be based on merit and qualifications rather than nepotism or personal connections. This ensures that individuals with the necessary skills and expertise are placed in positions of responsibility.

- Career Civil Servants: Bureaucratic systems often employ career civil servants who are committed to their roles and have long-term job security. This minimizes turnover and enhances organizational stability.

- Specialized Training: Bureaucracies provide specialized training to their employees to ensure they have the necessary skills and knowledge to perform their duties effectively.

- Official Record Keeping: Bureaucracies maintain detailed records of their activities and decisions. This practice helps ensure transparency, accountability, and the ability to review and assess past actions.

Max Weber believed that the bureaucratic form of organization was superior to other forms in terms of efficiency and effectiveness. He argued that it could provide stability, predictability, and the ability to manage complex tasks and processes effectively. Weber’s ideas were particularly influential in the context of government and public administration.

In the realm of public administration, Weber’s bureaucratic model provided a framework for organizing and managing government agencies. It promoted the idea of a professional civil service where individuals were selected and promoted based on their qualifications and competence rather than political patronage. This concept was especially important for the development of modern democratic states, where public administration needed to be impartial, efficient, and accountable to citizens.

However, Weber’s model of bureaucracy is not without its criticisms. Some argue that the strict adherence to rules and procedures can lead to inflexibility and a lack of responsiveness to changing circumstances. Others contend that bureaucracies can become overly hierarchical and resistant to innovation. Weber himself did not disagree with these criticisms.

While it has been both praised for its efficiency and criticized for its potential drawbacks, the bureaucratic model remains a central framework for understanding and managing complex organizations in the public and private sectors.

Neoclassical Organizational Theory

Neoclassical theory in public administration emerged in response to the shortcomings of classical bureaucratic theory and the changing demands of modern governance. This theoretical framework, which gained prominence in the mid-20th century, sought to address the limitations of bureaucracy and adapt public administration to contemporary challenges.

One of the central tenets of neoclassical theory is the emphasis on human behavior and motivation within organizations. Unlike classical theory, which portrayed public servants as passive, rule-following bureaucrats, neoclassical theorists recognized the importance of individual and group dynamics in public administration. Human behavior, they argued, is influenced by a range of factors, including individual goals, values, and organizational culture.

In neoclassical theory, organizations are viewed as social systems, and the study of public administration becomes an exploration of how individuals and groups interact within these systems. This perspective acknowledges the role of leadership, communication, and decision-making processes in shaping organizational outcomes.

Neoclassical theorists also emphasized the need for flexibility and adaptability in public administration. They recognized that rigid bureaucratic structures could hinder innovation and responsiveness to changing circumstances. As a result, neoclassical theory advocated for greater decentralization and delegation of authority, allowing organizations to be more nimble in their operations.

Furthermore, neoclassical theory introduced the concept of “management by objectives” (MBO) as a means of aligning individual and organizational goals. This approach emphasizes setting clear objectives and allowing employees greater autonomy in achieving them. Performance evaluations in MBO systems are often based on outcomes and results, rather than strict adherence to rules and procedures.

Overall, neoclassical theory in public administration represents a shift towards a more human-centered and adaptable approach to governance. It recognizes that public servants are not merely cogs in a bureaucratic machine but individuals with their own motivations and capacities. By embracing these principles, neoclassical theory aimed to make public administration more effective, responsive, and in tune with the evolving needs of society.

Herbert Simon and Bounded Rationality

Herbert Simon, a Nobel laureate economist and social scientist, played a pivotal role in shaping the neoclassical period in public administration through his groundbreaking work on decision-making and administrative behavior. Simon’s influence extended beyond economics and reached into the realm of public administration, where his ideas revolutionized the way scholars and practitioners understood administrative processes.

At the heart of Simon’s contribution was his exploration of “bounded rationality,” a concept that challenged the classical assumption of perfect rationality in decision- making. Simon argued that human beings, including public administrators, have cognitive limitations that prevent them from making fully rational choices. Instead, individuals rely on “satisficing,” a term coined by Simon, which means making decisions that are “good enough” rather than optimal. This perspective recognized that administrators often make decisions based on available information and resources, even if they are not ideal.

Simon’s work also emphasized the importance of organizational behavior and the decision-making processes within bureaucracies. He highlighted the significance of administrative discretion—the authority of administrators to make decisions within their areas of responsibility. This insight contributed to the understanding that organizational behavior and administrative processes were influenced by both rational and non-rational factors.

Furthermore, Simon’s ideas on “procedural rationality” introduced the notion that organizations should focus on designing decision-making procedures that enhance efficiency and effectiveness. This concept challenged the classical emphasis on hierarchical authority and bureaucracy.

In summary, Herbert Simon’s influence on the neoclassical period in public administration was profound. His insights into decision-making processes, bounded rationality, and administrative behavior revolutionized the field by recognizing the limitations of perfect rationality and advocating for more flexible and adaptive approaches to public administration. Simon’s work laid the foundation for a more human-centered and pragmatic approach to governance that continues to shape public administration theory and practice today.

Modern Structural Theory in Public Administration Management Theory

Modern Structural Theory is a significant advancement in the realm of public administration management theory. This theory places its focus on the structural dimensions of organizations and their profound influence on the behavior and performance of public administration entities. It underscores the critical importance of designing organizations with clear structures, delineated roles, and defined responsibilities to ensure the efficient execution of tasks. This perspective underscores the necessity of harmonizing organizational design with the mission and objectives of public administration.

Within the framework of Modern Structural Theory, the existence of hierarchical structures holds paramount significance. This theory acknowledges the prevalence of hierarchical frameworks in public administration, where decision-making authority is distributed across various management levels. It advocates for a well-defined chain of command as essential for expediting effective decision-making and coordination.

Moreover, Modern Structural Theory builds upon the principles of specialization and the division of labor, which were initially introduced in classical management theories. It posits that by assigning specific tasks to individuals in accordance with their skills and expertise, organizations can significantly boost efficiency and productivity.

In addition to specialization, the theory underscores the critical importance of coordinating and integrating efforts within an organization. Effective coordination and integration are deemed indispensable for the realization of organizational objectives. As such, the theory highlights the need for mechanisms that facilitate seamless communication and collaboration among diverse departments and units within public administration.

Standardization and adherence to established procedures are also promoted within this theory. It underscores the adoption of standardized processes to ensure consistency and reliability in the operations of public administration. Standardization is perceived as a means to mitigate errors and elevate the quality of services delivered to the public.

The theory recognizes the pivotal role of centralization and decentralization in influencing organizational performance. It encourages public administrators to make careful deliberations regarding the appropriate level of centralization in their specific context and in alignment with their objectives.

Although not its primary focus, Modern Structural Theory acknowledges the significance of organizational culture. A positive and conducive organizational culture can substantially enhance employee morale, motivation, and overall performance within the sphere of public administration.

Practically, Modern Structural Theory finds several applications within public administration:

- Reorganization: Public administrators can utilize this theory to assess and revamp their organizational structures to enhance efficiency and effectiveness, ensuring alignment with the mission and goals.

- Performance Enhancement: By identifying and addressing bottlenecks, redundancies, and inefficiencies through structural modifications, public administration entities can elevate their overall performance.

- Change Management: During the implementation of organizational changes, the principles of this theory can be applied to ensure a seamless transition, with structures, roles, and processes aligned with desired outcomes.

- Decision-Making: A profound understanding of hierarchical structures and authority distribution is vital for informed decision-making within public administration, and this theory provides valuable insights.

- Training and Development: Public administrators can employ this theory to craft training and development programs tailored to organizational structures and objectives, thereby enhancing employee skills and performance.

Modern Structural Theory in public administration management theory is centered on the structural facets of organizations and their influence on behavior and performance. It offers crucial insights into organizational design, hierarchy, specialization, coordination, and more. Public administrators can apply these principles to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of their organizations while aligning them with their missions and goals.

Peter M. Blau: Blau focused on formal organizational structures and their impact on behavior within organizations. He emphasized the role of hierarchy, authority, and communication in shaping organizational behavior. Blau’s research laid the foundation for understanding the relationship between organizational structures and individual behavior.

W. Richard Scott: Scott is known for his work on institutional theory, which explores how organizations conform to and are influenced by societal norms and values. His research highlights the importance of organizational structures in the context of larger institutional environments. Scott’s work has been influential in understanding how organizations adapt to external pressures and expectations.

James D. Thompson: Thompson’s research on organizations and technology introduced the concept of “contingency theory.” He argued that organizational structures should be contingent on various factors, such as the environment, technology, and goals. Thompson emphasized that there is no-one-size-fits-all approach to organizational design and that structures should be adapted to specific circumstances.

Paul Lawrence and Jay W. Lorsch: Lawrence and Lorsch’s work on contingency theory and differentiation explored how organizations can adapt to their environments. They emphasized the need for differentiation within organizations to match varying environmental demands. Their research highlighted the role of structural elements in achieving adaptation and effectiveness.

Tom Burns and G. M. Stalker: Burns and Stalker’s work on organic and mechanistic organizations explored how different structures respond to environmental changes. They introduced the concept of organic organizations, which are flexible and adaptable, and mechanistic organizations, which are more rigid and hierarchical. Their research emphasized the importance of aligning organizational structures with environmental demands.

Alfred D. Chandler, Jr.: Chandler is renowned for his studies on the evolution of organizational structures in response to changes in technology and markets. His research highlighted the role of structure in shaping the strategies and growth of large corporations. Chandler’s work provided historical insights into the development of modern organizational structures.

Systems Theory

The systems approach in organizational theory offers a unique perspective on understanding organizations. It conceptualizes an organization as a complex entity comprised of interconnected subsystems, each with distinct functions working collaboratively to achieve shared objectives. This perspective sets it apart from other schools of thought, such as the human behavior school, which primarily focuses on individual behavior within an organization. Systems theory, in contrast, takes a more comprehensive view, delving into the intricate components of the organizational system, their interactions, processes, and overarching goals.

While the human behavior school places significant emphasis on individual behaviors and their impact on others within an organization, systems theory broadens its scope to consider the entire organizational system and the interactions among its various elements. An essential aspect of systems theory is its recognition of the environment as a pivotal factor in understanding organizational dynamics. It acknowledges that the environment, both immediate and societal, directly and indirectly influences an organization’s internal workings.

An organization’s immediate environment involves entities such as customers, suppliers, regulatory bodies, and public opinion, while the broader societal environment encompasses social, cultural, economic, and political factors. Effectively managing an organization requires a deep understanding of these environments, particularly when navigating complex and uncertain conditions.

Systems theory emerged during a period of substantial technological advancement and intellectual growth, building upon the insights of earlier organizational theories. It addresses certain limitations found in classical and behavioral theories and offers a distinctive perspective characterized by its values, analytical level, and methodology.

One fundamental aspect of systems theory is its emphasis on the interconnectedness of all elements within a system. While individuals remain vital components of an organization, systems theory’s primary concern lies in comprehending the intricate relationships among these components. It recognizes that changes in one part of the system can reverberate throughout the entire organization, highlighting the importance of holistic thinking.

Moreover, systems theory acknowledges that there is no universally applicable approach to management and organization. Instead, it asserts that the effectiveness of strategies depends on the specific environmental context in which an organization operates. This adaptability to context is a key strength of systems theory.

In the realm of public administration management theory, systems theory has exerted a profound influence. It views public administration entities as intricate systems composed of interconnected and interdependent parts. This perspective underscores the significance of understanding how these parts interact and affect the overall functioning of public administration organizations.

Key concepts associated with systems theory in the context of public administration management include:

- Holism: Systems theory encourages a holistic perspective, considering public administration as a unified entity rather than a collection of isolated departments or units. This approach facilitates the analysis of government as a complete system, transcending individual components.

- Interdependence: The theory emphasizes the interdependence of various components within public administration. Government agencies, departments, and functions often rely on one another to achieve common goals and objectives, necessitating an understanding of these interdependencies for effective governance.

- Feedback Loops: Systems theory introduces the concept of feedback loops, mechanisms that enable organizations to monitor their performance and make necessary adjustments. In public administration, feedback loops are evident in performance measurement and evaluation processes, enabling governments to make informed decisions based on outcomes.

- Boundaries: Systems have defined boundaries that delineate their scope and interactions with the external environment. In public administration, understanding these boundaries is crucial for managing relationships between government organizations, citizens, and other stakeholders strategically.

- Open and Closed Systems: Systems theory categorizes organizations as open or closed systems. Public administration is typically viewed as an open system because government agencies engage with citizens, businesses, and other governmental bodies, interacting with and adapting to their external environment.

Applications of Systems Theory in Public Administration Management

Policy Development and Implementation: Systems theory assists in understanding the complexities of policy development and implementation by considering the interactions between various stakeholders, departments, and external factors. It helps policymakers anticipate potential consequences and unintended outcomes.

Organizational Design: Public administration organizations can benefit from systems theory when designing structures and processes. It allows for the examination of how different departments and functions interact and collaborate to achieve common objectives.

Performance Management: Systems theory supports the development of performance management systems in public administration. By recognizing the interconnectedness of organizational elements, it enables governments to set goals, monitor progress, and adapt strategies as needed.

Emergency Management: In crisis situations, systems theory can be applied to coordinate emergency responses. It helps identify critical dependencies, allocate resources efficiently, and establish effective communication networks among government agencies and responders.

Public Policy Analysis: Systems theory aids in analyzing public policies by considering their potential impacts on various parts of the governmental system. It helps policymakers assess the broader consequences of policy decisions.

Governance and Stakeholder Engagement: Understanding the interconnectedness of government agencies and stakeholders is vital for effective governance. Systems theory guides public administrators in engaging with citizens, interest groups, and businesses to address complex issues collaboratively.

An example of systems theory in public administration can be seen in the context of emergency management and disaster response. When a natural disaster, such as a hurricane or earthquake, occurs, government agencies at various levels (local, state, and federal) need to coordinate their efforts to provide an effective response and recovery process. Systems theory helps analyze and manage this complex scenario. Here’s how it works:

- Interconnected Components: In a disaster response system, there are multiple interconnected components, including government agencies (e.g., FEMA, local emergency management agencies), first responders (e.g., police, fire, medical personnel), resources (e.g., supplies, equipment), and affected communities.

- Interdependencies: These components rely on each other to achieve the common goal of mitigating the disaster’s impact and aiding in recovery. For instance, first responders need resources, logistics support, and clear communication channels to carry out their tasks effectively.

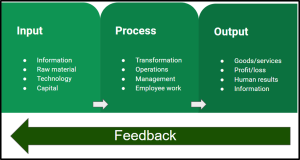

- Feedback Loops (Fig. 3.1): Systems theory involves feedback loops to monitor and adjust operations. In emergency management, feedback mechanisms can include real-time updates on the disaster’s progression, resource allocation, and the effectiveness of response efforts. Agencies use this information to adapt their strategies.

- Boundaries: The boundaries of the disaster response system are well-defined, encompassing the affected geographical area and the agencies involved. These boundaries help determine the scope of responsibilities and coordination efforts.

- Open System: Emergency management is considered an open system because it interacts with the external environment, including affected communities, volunteers, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These external entities often play crucial roles in disaster response and recovery.

- Holistic Perspective: Systems theory encourages a holistic perspective, considering the entire disaster response network, including the interactions between various stakeholders, agencies, and resources.

- Resource Allocation: During a disaster, efficient resource allocation is critical. Systems theory helps prioritize resources by assessing their availability, demand, and the needs of affected areas.

- Communication Networks: Effective communication is essential for coordination. Systems theory emphasizes the need for clear communication channels and real-time information sharing among all involved parties.

By applying systems theory to emergency management, public administrators can better understand the complex dynamics of disaster response and improve their ability to coordinate efforts, allocate resources, and adapt to changing circumstances. This approach enhances the overall effectiveness of the response and helps minimize the negative impacts of disasters on affected communities.

Systems theory has become an invaluable framework in the field of public administration management theory. It offers a comprehensive approach to analyzing, designing, and managing government organizations, emphasizing the interconnectedness and interdependencies that characterize the public sector. By adopting a systems perspective, public administrators can better navigate the complexities of governance and enhance their ability to achieve desired outcomes.

New Public Management

New Public Management (NPM) is a significant paradigm shift in the field of public administration and management that gained prominence in the late 20th century. This approach emerged as a response to growing concerns about the inefficiencies and limitations of traditional bureaucratic models of governance. NPM represents a departure from the conventional, hierarchical, and rule-bound approach to public administration by adopting principles inspired by the private sector. Its overarching aim is to enhance the efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability of public services.

At the core of NPM is the fundamental idea that public sector organizations should be managed and operated with the same rigor and effectiveness as private businesses. This shift implies a focus on outcomes, cost-efficiency, and customer satisfaction. Public managers are expected to prioritize results over processes, aiming for cost-effective solutions while ensuring that the needs of citizens and service users are met.

One of the defining features of NPM is the decentralization of decision-making authority. This approach emphasizes devolving power and decision-making to lower levels of government and public organizations. By doing so, NPM aims to foster greater responsiveness to local needs, encourage innovation, and reduce bureaucratic red tape.

Marketization is another key principle of NPM. This entails introducing market-like mechanisms and competition into the public sector. Governments may contract out services to private firms or use performance-based contracting to incentivize competition among service providers. The goal is to leverage competition to drive efficiency improvements and enhance service quality.

A customer-centric approach is also fundamental to NPM. Public services are designed and delivered with a strong emphasis on meeting the needs and preferences of citizens and service users. Feedback mechanisms and responsiveness to customer complaints are integral components of this approach.

Measuring performance and outcomes is a cornerstone of NPM. Public organizations set clear performance targets and use measurable indicators to track progress toward these targets. Accountability for results is a central tenet, and performance data is often made publicly available to promote transparency and enhance accountability.

NPM encourages public organizations to be flexible and innovative in their approaches. This involves experimenting with new service delivery models, adopting emerging technologies, and embracing innovative management practices. The goal is to adapt to changing circumstances and improve service delivery.

Key components and tools associated with NPM include the contracting out of public services, performance-based budgeting, e-government initiatives, benchmarking, devolution of authority, and robust performance evaluation mechanisms. These components collectively contribute to the implementation of NPM principles.

While NPM has demonstrated success in enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of public services in many instances, it has also faced criticism and controversies. Critics argue that the relentless pursuit of efficiency may lead to a narrow focus on cost-cutting, potentially compromising service quality and equity. The introduction of market principles into the public sector has raised concerns about the potential privatization of essential services and its impact on public interest and equity. Additionally, crafting meaningful performance indicators and accurately measuring complex public services can be challenging, and overreliance on quantitative metrics may oversimplify performance assessments. Lastly, implementing NPM principles can encounter resistance from entrenched bureaucratic cultures and labor unions, posing challenges to successful transformation.

NPM represents a significant departure from traditional public administration, emphasizing efficiency, decentralization, market mechanisms, customer-centricity, and performance measurement. While it has achieved notable successes, it continues to be a subject of debate and evolution in the realm of public management practices. Striking the right balance between efficiency, equity, and accountability remains an ongoing challenge.

Summary

Modern management finds its roots in the military institutions of ancient civilizations. While various ancient kingdoms like Egypt and China possessed advanced administrative systems, the fundamental principles of modern public administration, especially in the Western world, can be traced back to the Roman Empire.

Every organization operates under a management doctrine that mirrors the core values of its cultural context. The viability of any management approach hinges on these guiding doctrines and the corresponding behavioral methods for their implementation. The first versions of these doctrines were authoritarian in nature, closely resembling the strict discipline of the military. Over time, military institutions developed principles for the effective management of their authoritarian structures. Some of these principles, with relevance in civilian contexts, have been incorporated into modern management practices. As a result, concepts that were originally military in nature, such as “span of control” and “unity of command,” have become integral to civilian management.

Progress in organizational theory is not simply the accumulation of knowledge and facts; rather, it revolves around the dominant theory or model adopted during a specific era. Instead of refuting earlier theories, each new theory builds upon existing knowledge and theories. Once a theory gains consensus acceptance, it persists as long as it remains useful, eventually giving way to a more salient theory.

Classical organization theory, which includes the concept of bureaucracy, marked the beginning of this field and is often considered traditional. It serves as the foundation upon which other schools of organization theory have been constructed. In the late 19th century, American industrial engineers began advocating for the scientific design of work in factories to enhance worker productivity. Scientific management emerged from this production perspective, with its focus on research and planning to make organizations more competitive.