Chapter 6: Public Budgeting and Finance

The budgetary process is an essential component of the United States government. It is a system of planning and allocating financial resources to fund government programs, initiatives, and services. In this chapter, we will explore the budgetary process at both the federal and state levels in the United States, its functions, structure, and criticisms.

The essential circulation and control of financial resources form the life force of our public administration structure. Regardless of how visionary a policy might be or how meticulously crafted an administrative performance system is, its functionality hinges on its alignment with the movement of funds that enable its execution. Just like the preceding aspects of the narrative of public administration, the framework for managing public finances is built upon years of adopted designs and improvements. Administrators must grasp the system’s design, its intended purpose, its capabilities, and notably, its limitations. Much like the government’s mechanics and the intergovernmental relations system, many elements of the design of the American public financial management system trace back to our fundamental political traditions and agreements – the notions of the Constitutional Convention’s founders. Conversely, certain elements, like the welfare state concept, have roots only a few generations deep. Meanwhile, ideas such as the notion of “user fees” are currently at their pinnacle.

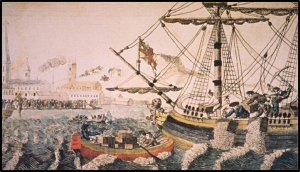

Think back to every American history class that you took growing up. Remember the Boston Tea Party? This act of rebellion way back in 1773 set the stage for the structure of America’s public financial management system. By heaving the tea into Boston Harbor instead of paying what they considered unreasonable taxes to England, protesting, “No taxation without representation”, they were asserting what would end up being a guiding principle for the country’s forthcoming public financial management system. They insisted that taxes and spending should be subject to approval through democratic processes, essentially receiving the endorsement of the democratic populace. This differed from the way that most governments had operated to this point, as the imposition and collection of taxes had historically been used as an exercise of authority and spending had occurred at the sole discretion of the governing powers. Adding the element of democratic consent to financial matters was a critical turn for the operations of representative government and six core principles became central to the formation of the American public financial management system.

#1 Accountability

Responsibility for public funds is a fundamental aspect of public financial management. Essentially, this principle dictates that individuals entrusted with the task of managing public finances must be held responsible for them. These individuals overseeing the utilization of public funds also need to provide a comprehensive account of how these funds are used. The establishment of accountability can be achieved by means of audits and assessments carried out by legislative bodies.

#2 Probity

Probity, or integrity, is another cornerstone within the framework of public financial management. It is crucial for all lawmakers and administrators to bear in mind that although these funds are under their control, they are not meant for personal enrichment. Consequently, the utilization of public funds must be characterized by the highest standards of honesty and integrity. This principle of financial management seeks to emphasize precisely this message.

#3 Prudence

Individuals who have been entrusted with the responsibility of managing these funds must never utilize these public funds to engage in unnecessary or unjustifiable risks. Whether the motivation behind such actions is their personal gain or the supposed benefit of the public, it remains unacceptable. These funds are explicitly designated for the betterment of the public’s welfare.

#4 Equity

The government, for its part, should ensure equitable distribution and allocation of these funds. This principle of managing public funds emphasizes the notion that individuals should experience equal treatment and consideration under comparable circumstances, both in the process of collecting and disbursing taxes.

#5 Transparency

Transparency entails that the actions and operations of the government when it comes to managing these funds are accessible and evident to everyone. The methods they employ to generate these funds should also be presented for public scrutiny. This extends to the actions our leaders undertake with the public funds allocated to their respective domains.

#6 Democratic Consent

This tenet of financial management asserts that “the consent of the governed must be fully represented.” This means that prior to any significant step concerning these public funds, the proprietors, who are the populace, must be informed and their desires respected. This encompasses the principle of no taxation without representation, and expenditures must similarly undergo democratic endorsement.

These guiding principles are aspirational, but in reality they frequently face challenges and violations. This is especially important to understand, as the public financial management system is, in many ways, the framework for the rest of the public sector. The strength of this system is necessary for the successful operation of the government.

Dimensions

Budgeting is the foremost pivotal process for decision-making within public institutions. Simultaneously, the budget serves as the principal point of reference for a jurisdiction. In its increasingly expansive formats, budgets not only document the outcomes of policy decisions but also outline policy priorities and program objectives, effectively mapping out a government’s comprehensive service endeavors. The public budget can be seen as encompassing four fundamental dimensions.

#1 Political

A public budget serves not only as a financial roadmap but also as a potent political instrument that shapes the priorities and policies of a government. At its core, a budget allocation reflects the values and objectives of the ruling party or administration, thus making it a reflection of political ideology and vision. Through the process of budget formulation and allocation, policymakers make choices that can either garner public support or face resistance. Each allocation decision signifies a trade-off, wherein the allocation of funds to one sector often means a reduction in resources for another. This inherent decision-making process is imbued with political considerations, as it involves negotiating the interests of various stakeholders, including citizens, interest groups, and even opposition parties.

Moreover, the presentation of a public budget can sway public opinion and elicit responses from the electorate. Governments use budget announcements as a platform to communicate their accomplishments and demonstrate their commitment to addressing critical issues. By highlighting allocations to popular sectors such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure, governments seek to gain public approval and strengthen their political standing. Conversely, budgetary decisions that are perceived as neglecting key areas or favoring certain groups can trigger backlash and public protests. Opposition parties also play a crucial role in using budget debates as opportunities to criticize the ruling party’s priorities, thus turning the budget process into a political battleground.

In essence, a public budget transcends its financial role to become a reflection of political power dynamics, policy priorities, and the public’s perceived representation. It shapes the trajectory of a government’s tenure by influencing public sentiment, garnering support, and ultimately affecting the distribution of resources in a society.

#2 Managerial

A public budget operates as a vital managerial tool that guides the efficient allocation and utilization of resources within a government. It provides a structured framework for decision-making by outlining financial limits and priorities, ensuring that available resources are channeled toward achieving specific goals. Through the budgeting process, government agencies and departments are compelled to identify their objectives and align their activities with the overall mission of the administration. This promotes accountability and transparency, as the budget serves as a roadmap that stakeholders can use to assess whether funds are being used effectively to achieve the desired outcomes.

Additionally, a public budget enables prudent financial management by promoting fiscal discipline and control. It assists in forecasting revenue streams and estimating expenditures, which aids in preventing overspending or budget deficits. The budgeting process requires agencies to justify their resource needs, fostering a culture of efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Moreover, the budget’s tracking and reporting mechanisms facilitate ongoing monitoring of expenditures, allowing timely adjustments if discrepancies or inefficiencies arise. As a managerial tool, the budget empowers decision-makers to allocate resources in line with priority areas and respond flexibly to changing circumstances, ultimately enhancing the government’s ability to provide essential services and implement policies effectively.

#3 Economic

A public budget serves as a powerful economic tool that influences a nation’s overall economic health and stability. Through its allocation of resources, the budget can impact economic growth, employment rates, and income distribution. Investment in sectors such as infrastructure, education, and research and development can stimulate economic activity and drive growth. Conversely, responsible budgeting practices that focus on reducing deficits and managing public debt can help maintain economic stability, prevent inflation, and foster investor confidence. The budget also plays a role in income redistribution by allocating funds for social welfare programs and targeted interventions to address income disparities, thus contributing to a more equitable society.

Furthermore, the budget has the capacity to steer economic policy by reflecting government priorities and strategies. Tax policies and rates, for instance, are closely linked to the budget process and can be used to incentivize desired economic behaviors, such as saving or investing. The budget can also influence trade and industry policies, affecting sectors’ competitiveness and growth prospects. Government expenditures can act as an economic stabilizer, increasing during economic downturns to stimulate demand and decreasing during periods of high growth to prevent overheating. In this way, the budget’s economic role extends beyond fiscal management to actively shaping the broader economic landscape of a nation.

#4 Accounting

A public budget functions as an essential accounting tool that provides a systematic framework for recording, tracking, and managing financial transactions within a government. It establishes a comprehensive record of expected revenues and planned expenditures, creating a basis for accurate financial reporting and analysis. By categorizing revenue sources and expenditure items, the budget facilitates transparent financial documentation, enabling auditors and stakeholders to scrutinize financial records for accuracy and compliance with regulations. This accounting aspect of the budget is critical in maintaining the integrity of public finances and ensuring that funds are utilized in a responsible and accountable manner.

Moreover, the budget’s accounting function supports effective financial management by providing a benchmark against which actual financial performance can be measured. Regularly comparing budgeted figures to actual figures allows for the identification of discrepancies, enabling timely corrective actions to be taken. This process promotes efficient resource allocation, as decision-makers can adjust plans based on real-time financial data. The budget’s accounting role also aids in long-term financial planning, helping governments forecast revenue trends, assess potential risks, and plan for contingencies. Overall, the budget serves as a reliable accounting instrument that enhances financial transparency, accountability, and informed decision-making within the realm of public administration.

Budget Analysis

In their work “Public Finance in Theory and Practice,” Economists Richard and Peggy Musgrave offer a fundamental insight into comprehending the objectives underlying public financial management. They suggest that the process of taxing and spending is driven by one of four main objectives:

- Allocation: Ensuring that adequate funds are directed towards sectors of the economy where they are most needed.

- Distribution: Guaranteeing that the distribution of public funding among regions, societal classes, public and private sectors, and government and business aligns with public policy objectives.

- Stabilization: Utilizing public expenditure to stabilize the broader economy or specific segments, in line with Keynesian principles.

- Growth: Harnessing government spending as a tool to foster economic expansion and the creation of wealth.

When we analyze the budget of a national, state, or local government, we can use this framework. Does the budget primarily focus on promoting economic growth? If so, what strategies are employed? Perhaps it involves lower taxes on businesses and reduced government regulations. Is the budget designed to achieve distributional goals? It might seek to assist urban areas or provide support for the long-term unemployed. Alternatively, the budget might aim to stabilize the economic cycle, either by boosting demand during a downturn or tempering it during an upswing.

Disagreements often arise concerning the methods used to attain these stated objectives. Advocates of supply-side economics, for instance, believe that reducing tax rates encourages fresh capital inflow, leading to job creation, economic growth, and ultimately increased tax revenues. This concept, associated with the Reagan administration, is colloquially referred to as Reaganomics, even though Reagan’s economic policies were not solely supply-side.

The basis of supply-side economics can be traced back more than two centuries, with Alexander Hamilton presenting a similar argument in The Federalist, No. 21 (1787). Hamilton noted that taxes inherently establish their own limits and should not exceed levels that hinder revenue expansion. If duties become too burdensome, consumption declines, revenue collection is evaded, and the overall treasury yield diminishes. Not everyone agrees with this philosophy, however. The motivations and objectives underlying budgetary strategies are not always clearly articulated by politicians. Sometimes, objectives driven by political expediency, such as tax loopholes for campaign supporters, are not openly acknowledged. The growing complexity and intricacy of budgets often result in responsible individuals not fully grasping the implications of their actions. Even David A. Stockman, who served as Reagan’s Director of the Office of Management and Budget, candidly admitted in 1981 that none of them truly comprehended the full implications of the numbers and complexities involved in budgetary matters.

Keynes and Hayek

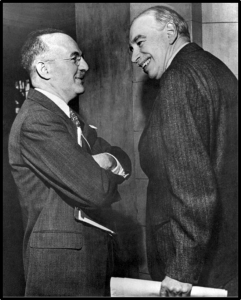

John Maynard Keynes, a prominent economist of the 20th century, left a lasting impact on American public budgeting through his revolutionary ideas and theories. Keynesian economics, developed during the aftermath of the Great Depression, emphasized the role of government intervention in stabilizing economies. This philosophy significantly influenced the way the United States approached public budgeting, especially during times of economic crises and in the pursuit of economic growth.

Keynes argued that during economic downturns, traditional market forces might not be sufficient to restore economic equilibrium. In response, he proposed that governments should step in to stimulate demand through increased public spending, even if it meant running budget deficits. This concept of deficit spending during economic slumps became a cornerstone of Keynesian economics and found its way into American budgeting practices.

During the mid-20th century, particularly after World War II, Keynesian principles guided American economic policy and public budgeting. The idea that government expenditure could effectively combat unemployment and stimulate economic activity gained prominence. This perspective was notably embraced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies, which aimed to alleviate the effects of the Great Depression through massive public works projects, job creation, and social welfare programs. The New Deal’s expansionary budgeting approach aligned with Keynesian thinking and played a vital role in the recovery of the American economy.

Keynesian influence persisted beyond the New Deal era. In the 1960s, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs, including initiatives to combat poverty and promote civil rights, exemplified the integration of Keynesian principles into public budgeting. These programs involved increased government spending on social services, education, and healthcare, aimed at improving the well-being of citizens and stimulating overall economic growth.

However, the 1970s marked a turning point in the application of Keynesian economics to American public budgeting. The era witnessed stagflation—a combination of stagnant economic growth and high inflation—challenging the efficacy of Keynesian policies. Critics argued that deficit spending might lead to long-term economic issues, including inflation and debt accumulation. This criticism prompted a reevaluation of Keynesian strategies and contributed to the rise of supply-side economics, advocating for tax cuts and deregulation to stimulate economic growth.

Nonetheless, Keynesian ideas persisted in certain contexts. The notion of counter-cyclical fiscal policy, which involves increasing government spending during recessions and decreasing it during economic booms, remained a consideration in budgetary discussions. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, enacted in response to the global financial crisis, exemplified this approach. The Act involved substantial government spending to boost demand and counter the economic downturn.

The influence of John Maynard Keynes on American public budgeting is undeniable. His emphasis on the role of government intervention, deficit spending during economic downturns, and the importance of stimulating demand left a lasting impact on American economic policy and public budgeting practices. While the applicability of Keynesian economics faced challenges and evolved over time, its core principles shaped pivotal moments in American history, from the New Deal to modern responses to economic crises. Keynes’s ideas continue to be part of the ongoing discourse surrounding economic policy and public budgeting strategies in the United States. Even President Richard M. Nixon conceded, “We’re all Keynesians now.”

Friedrich Hayek, a prominent Austrian economist and philosopher, has also significantly influenced American public budgeting through his advocacy for limited government intervention, individual liberty, and free-market principles. Hayek’s ideas, often associated with classical liberalism and libertarianism, have left a lasting impact on the way the United States approaches economic policy and public budgeting, shaping debates about the appropriate role of government in the economy.

Hayek’s most notable work, “The Road to Serfdom,” warned against the dangers of government intervention and central planning, arguing that such interventions could lead to a loss of individual freedom and a slide towards authoritarianism. His views on the importance of limited government and the spontaneous order of markets resonated with many American policymakers and thinkers, especially those aligned with conservative and libertarian ideologies.

Hayek’s influence on American public budgeting can be observed in the promotion of fiscal conservatism and efforts to restrain government spending. His emphasis on the potential negative consequences of deficit spending and the accumulation of public debt has informed debates about the sustainability of expansive government budgets. Advocates of Hayekian principles argue that excessive government spending can lead to distortions in the market, crowding out private investment and impeding economic growth.

Throughout American history, policymakers who share Hayek’s concerns about government intervention have sought to limit the scope and size of government expenditures. This perspective gained prominence during the Reagan administration in the 1980s. President Ronald Reagan, influenced by Hayek’s ideas, championed tax cuts, deregulation, and reductions in government spending as a means to promote economic growth and individual liberty. These policies were in line with Hayek’s belief in the power of market forces to allocate resources efficiently and drive innovation.

Hayek’s influence also extends to ongoing debates about entitlement programs and the social safety net. Critics of expansive welfare programs often draw on Hayek’s arguments against top-down planning and emphasize the potential disincentives to individual initiative that can arise from generous government support. While discussions surrounding these programs are complex and multifaceted, Hayek’s principles continue to play a role in shaping policy discussions about the balance between providing a safety net and avoiding dependency on government assistance.

Friedrich Hayek’s ideas have significantly shaped American public budgeting by promoting limited government intervention, individual freedom, and free-market principles. His emphasis on the potential dangers of government planning and excessive spending has influenced debates about fiscal responsibility and the appropriate scope of government involvement in the economy. While his ideas have faced criticism and evolved in the face of changing economic realities, Hayek’s contributions to economic thought have left an indelible mark on the way the United States approaches economic policy and public budgeting.

Federal Government Budgetary Process

Fiscal pertains to matters related to taxation, public income, or public debt.

The annual federal budget process doesn’t exist due to a single piece of legislation. Instead, Congress shapes spending and tax determinations through an array of legislative actions, a practice that has developed over more than two centuries. The Constitution explicitly vests Congress with control over financial matters, bestowing it with the authority “to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises.” It also stipulates that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by law.” In essence, federal taxation and expenditure necessitate legislative enactment to become legally binding.

Within this framework, some tax and spending laws maintain permanence until modified, which frequently occurs. Other statutes span multi-year intervals, prompting the need for periodic renewal. Moreover, numerous budget choices are made on an annual basis through the enactment of yearly appropriations bills. Furthermore, the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 establishes an internal procedure known as a congressional budget resolution. This process is designed for Congress to devise and uphold an annual comprehensive plan for addressing budget-related legislation, though Congress has increasingly opted to disregard this procedure.

The fiscal year is a 12-month accounting period not tied to the regular calendar year. Historically, the fiscal year for the federal government commenced on July 1 and concluded on June 30, extending back to fiscal year 1976. However, due in part to increased activity in Washington during the summer months facilitated by air conditioning, Congress shifted the fiscal year’s commencement to the end of summer. Thus, since fiscal year 1977, the federal government’s fiscal year starts on October 1 and concludes on September 30. The fiscal year is identified by the calendar year in which it ends (e.g., fiscal year 2010 concluded on September 30, 2010). Not all state and local governments mirror the federal model. While most states start their fiscal year on July 1, a few adopt the first day of April, September, or October.

President

Traditionally commencing the annual federal budget process, the President presents an exhaustive budget request for the upcoming fiscal year, set to commence on October 1. (While this request should be submitted by the first Monday of February, occasional delays arise, particularly during new administrations or when prior year’s budget-related congressional actions have been postponed.) This budget request, shaped through an interactive collaboration between federal agencies and the President’s Office of Management and Budget, a process that usually initiates the preceding spring or earlier, holds three vital roles.

Firstly, it serves as the conduit for the President’s recommendations regarding the broader federal fiscal strategy, encompassing: (a) the proposed federal spending for public objectives; (b) the envisaged tax revenue to be amassed; and (c) the targeted deficit (or surplus), denoting the disparity between (a) and (b). Most years witness federal expenditures exceeding tax income, with resulting deficits predominantly financed through borrowing (as indicated in the chart).

Secondly, the President’s budget outlines the administration’s comparative priorities for federal programs, delineating allocations for defense, agriculture, education, healthcare, and other domains. The budget assumes a notably detailed stance, presenting funding levels for individual “budget accounts,” which encompass federal programs or smaller clusters of programs. It typically charts fiscal policy and budget preferences not just for the ensuing year, but also for the ensuing nine years. Accompanying this budget are supplementary volumes, including historical tables detailing past budgetary outcomes.

Lastly, the President’s budget often incorporates proposals to modify certain mandatory programs and specific facets of revenue regulations, even if Congress is unlikely to deliberate upon these suggestions. Furthermore, the budget provides updated projections of predicted expenditures for ongoing mandatory programs and revenues, even in instances where no adjustments to these programs are advocated. This ensures that the cumulative budget figures, signifying overall fiscal policy, are grounded in more recent data.

Typically, Congress holds hearings to question administration officials regarding their requests, however because of how the Constitution divvies up responsibilities, they are under no obligation to adhere to the President’s budget. Congress tends to use it as a guideline, and certainly important information about the cost of running departments and programs are included in the President’s budget, but when it comes down to it the President does not have the authority to set taxing and spending levels.

Congress

After a review of the President’s proposed budget, Congress constructs its own financial blueprint, called a “budget resolution.” The responsibility of formulating and enforcing the congressional budget resolution rests with the House and Senate Budget Committees. Following their approval, these resolutions are presented to the House and Senate chambers, where they remain open to amendments. The budget resolution for the year gains approval when both the House and Senate adopt the same version, either following negotiations on a conference agreement or by one chamber endorsing the resolution adopted by the other.

The congressional budget resolution is a “concurrent” resolution, which unlike most other bills, is exempt from being presented to the President for signing or vetoing. Additionally, it is one of the rare measures not susceptible to filibustering in the Senate, thus necessitating only a majority vote for passage or amendment. As it doesn’t proceed to the President, the budget resolution lacks the capacity to establish spending or tax law. Instead, it sets objectives for congressional committees to propose legislation directly related to funding allocation or modifications to spending and tax statutes. Furthermore, it can institute an expedited process termed “reconciliation” for addressing changes in mandatory spending and tax matters.

The aim is for Congress to endorse the budget resolution by April 15, giving them 5½ months to work before the end of the fiscal year, however, this timeline is often extended. In recent years, it has also become common for Congress to forgo passing a budget resolution entirely. Instead, an alternative approach involves the House and Senate agreeing upon “deeming resolutions” or statutory provisions to supplant the budget resolution.

In contrast to the extensively detailed President’s budget, the congressional budget resolution adopts a more straightforward format. It comprises a series of figures that outline the suggested expenditure amounts for 19 distinct spending classifications, referred to as budget “functions,” alongside the projected aggregate government revenue for each of the upcoming five years or beyond. The disparity between these two cumulative sums — the upper spending limit and the lower revenue threshold — signifies the anticipated annual deficit (or surplus).

The spending figures in both the President’s budget and the budget resolution are presented in two distinct ways: the total amount of “budget authority,” which denotes allocated funding, and the projected level of expenditures, termed “outlays.” Budget authority signifies the sum of money that Congress permits a federal agency to commit for future expenditures, while outlays indicate the actual monetary flow from the federal Treasury within a given year. To illustrate, consider a bill that designates $500 million for building a military base; this allocates $500 million in budget authority for the upcoming year. However, the outlays may not reach $500 million until the subsequent year or even later, once the base’s planning and construction have concluded.

Within both the House and Senate, the Appropriations Committee receives a solitary 302(a) allocation covering all its programs. Subsequently, each Appropriations Committee determines the distribution of this funding among its 12 subcommittees to create 302(b) sub-allocations. For committees overseeing mandatory programs, a 302(a) allocation is allocated, signifying an overarching financial limit for all mandatory expenditures within their purview.

After the adoption of the budget resolution, Congress directs its attention to the annual appropriations bills, which allocate funds for discretionary programs within the upcoming fiscal year. Additionally, Congress may deliberate on measures aimed at enacting modifications to mandatory spending or revenue levels, which must remain within the confines of the spending caps and revenue thresholds prescribed in the budget resolution, as well as the associated 302(a) allocations. Procedures are in place to uphold the stipulations of the budget resolution while contemplating such legislation. If appropriations bills are not enacted by the commencement of the fiscal year, Congress must undertake specific measures to avert the disruption of government services–a shutdown.

The primary mechanism ensuring compliance with the budget resolution’s terms and preventing the passage of legislation that violates them is the authority of a single member from either the House or Senate to raise a budget-related “point of order” on the floor, effectively blocking such legislation. In recent times, this point of order has held less significance in the House due to its potential waiver within the “rule” that outlines the conditions governing the consideration of each bill on the floor. These rules, established through resolutions that the House can adopt with a simple majority vote, are formulated by the Rules Committee, a body appointed by the leadership. On the other hand, the budget point of order carries substantial weight within the Senate. In this chamber, any legislation surpassing a committee’s assigned spending allocation or reducing taxes below the level allowed in the budget resolution (revenue floor) is susceptible to a budget point of order on the Senate floor. To overcome this point of order, a waiver necessitates a 60-vote majority. Failing to secure a waiver leads to the termination of the bill’s consideration on the Senate floor.

What if there is no budget resolution?

Congress has rarely managed to finalize action on the budget resolution by the specified April 15 deadline outlined in the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. Additionally, although Congress endorsed a budget resolution for the initial 23 years after the enactment of the Budget Act (from 1976 to 1998), it encountered difficulty in passing a resolution for the majority of years spanning between 1999 and 2023. In the absence of a new budget resolution, the spending limitations and revenue baseline from the prior resolution automatically extend to cover the remaining years of that resolution.

However, as the prior budget resolution exclusively set an allocation for the Appropriations Committees for the previous year, these committees lack an official funding objective for the upcoming year. This absence of a funding target renders each of the 12 appropriations bills vulnerable to a point of order. To circumvent this and other potential procedural challenges arising due to the absence of a new budget resolution, the House and Senate might come to an agreement on distinct budget targets, often with significant delays. These targets are “deemed” to substitute the budget resolution. These deeming resolutions could concentrate solely on a new appropriations target or they could introduce new revenue floors and targets for the other committees.

At times, Congress has adopted a divergent approach, instituting a “Congressional Budget” via legislation as an alternative to the concurrent budget resolution. This approach involves setting fresh appropriations targets for discretionary programs. For instance, this was observed in a series of “bipartisan budget acts” (enacted in 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2019) that reflected outcomes from negotiations aimed at elevating the funding limits on defense and non-defense appropriations established by the 2011 Budget Control Act. Since both deeming resolutions and the statutory course followed in the bipartisan budget acts serve as substitutes for regular budget resolutions, they trigger the same budgetary points of order.

Should Congress fail to finalize action on an appropriations bill before the onset of the fiscal year on October 1—a scenario observed in every fiscal year since 1997 and in 40 out of the last 43 years—a contingency measure called a continuing resolution (CR) must be sanctioned by Congress and subsequently signed by the President. This CR offers interim funding for agencies and programs affected by the situation. In instances where Congress doesn’t endorse the CR or the President withholds their signature (due to disputes concerning its content), agencies and programs dependent on annual appropriations but not yet allocated funding must, to a large extent, halt their operations.

For instance, a disagreement between President Trump and congressional Democrats regarding border wall funding resulted in a federal agency shutdown across nine distinct departments for 35 days, starting from December 22, 2018. Similarly, a clash between President Obama and congressional Republicans over the funding of health reform legislation caused a 16-day cessation of regular government activities beginning October 1, 2013. In the winter of 1995-96, a disagreement between President Clinton and congressional Republicans prompted a 21-day shutdown of substantial segments of the federal government.

Budget Reconciliation

The budget “reconciliation” process, as established in the Congressional Budget Act, is a specialized procedure that expedites the deliberation of spending and tax legislation. Initially conceived as a tool for reducing deficits, this procedure compelled committees to generate spending cuts or tax hikes as stipulated in the budget resolution. Sixteen deficit-reduction reconciliation bills have been enacted, including the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Nevertheless, this process has also been used to elevate deficits, such as enacting tax cuts during the George W. Bush Administration and under the Trump Administration in 2017, along with passing a COVID-19 relief bill during the Biden Administration in 2021. Despite its optional nature, the procedural benefits it offers have prompted Congress to increasingly utilize it for major spending and tax adjustments. Presently, the most common trigger for a budget resolution is to initiate the reconciliation process.

To commence the reconciliation process, both the House and Senate must adopt a budget resolution that features a “reconciliation directive.” This directive instructs one or more committees to produce legislation adhering to specific spending or tax targets by a designated deadline, although the target can also involve a directive to “alter the (projected) deficit” by a set amount. If a committee fails to draft such legislation, the Budget Committee chair generally reserves the right to propose floor amendments in line with the reconciliation target for the committee, typically resulting in compliance with the directive. After committees formulate legislation in accordance with the reconciliation directive, the Budget Committee consolidates all these measures into a singular “reconciliation bill” presented on the floor. Reconciliation rules exempt the bill from filibusters, and debate is limited to 20 hours, with tighter restrictions on amendments. As a result, the Senate can swiftly consider and pass a reconciliation bill relative to other contentious legislation, which faces filibusters and requires a three-fifths majority vote for progression.

Historically, reconciliation bills have predominantly impacted mandatory programs in terms of spending adjustments. Yet, in some instances, notably in 2021, additional funding for discretionary programs has been directly incorporated by the committees possessing authorizing jurisdiction over those programs, bypassing the Appropriations Committees. Consequently, the House and Senate committees receiving reconciliation instructions have consistently comprised a) the tax committees (House Ways & Means and Senate Finance); b) authorizing committees overseeing mandatory spending programs; and c) authorizing committees rather than the Appropriations Committees, even if direct funding alterations for otherwise discretionary programs are anticipated.

While reconciliation allows Congress to modify spending and tax legislation with a majority vote, it encounters a significant restriction—the “Byrd Rule,” named after the late Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia. This Senate rule enforces a point of order against any provision in a reconciliation bill (or its amendment) that is deemed “extraneous” to the purpose of amending spending or tax law. If a point of order is raised under the Byrd Rule, the contested provision is automatically removed from the bill unless at least 60 senators vote to waive the rule. This hinders the inclusion of policy changes in a reconciliation bill unless they bear direct fiscal implications— and these fiscal effects must surpass being “merely incidental” to the non-budgetary aspects of the provision. This rule also disallows modifications to discretionary appropriations authorizations, which will be financed in later appropriations bills rather than the reconciliation bill. Likewise, alterations to civil rights, employment law, or even the budget process are restricted by the Byrd Rule. Changes to Social Security are also barred, even if they pertain to budgetary matters. Additionally, the Byrd Rule prohibits any spending increments or tax reductions that incur costs beyond the timeframe covered by the reconciliation directive—five (or typically ten) years—unless other provisions in the bill fully offset these “outside-the-window” expenses.

Alongside the parameters established during the annual budget process under the Congressional Budget Act, Congress has frequently operated within statutory budget-control mechanisms designed to prevent tax and mandatory spending changes from escalating the deficit, or to restrict discretionary spending.

One example of this is PAYGO. Enacted in 2010, the Statutory Pay-As-You Go (PAYGO) Act mandates that any legislative adjustments to taxes or mandatory spending that amplify projected deficits must be counterbalanced or funded by other alterations to taxes or mandatory spending that diminish deficits by an equivalent magnitude. Similarly, the 1990 Budget Enforcement Act (BEA) and the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) each imposed temporary, legally enforceable thresholds or “caps” on the level of discretionary appropriations. The BEA limits lapsed after 2002, while the BCA limits terminated after 2021. Both PAYGO and discretionary funding caps are enforced through “sequestration” — broad-based reductions in specified programs. In the case of PAYGO violations, across-the-board cuts in designated mandatory programs would be triggered at the conclusion of each Congress session to restore the equilibrium between the expenses and savings stemming from previously enacted mandatory spending or revenue changes. However, Congress frequently bypasses the Statutory PAYGO Act by exempting certain expenses from its sequestration stipulations, resulting in no sequestration under Statutory PAYGO thus far. Similarly, appropriations surpassing the discretionary funding caps would activate across-the-board reductions in appropriated programs to eliminate the excess. The sole significant sequestration transpired in 2013 to adhere to the funding limits outlined by the 2011 Budget Control Act.

Debt Limit

Public budgeting encompasses legislation for generating revenue and financing programs. In instances where the revenue falls short of covering the ensuing expenditure, the Treasury resorts to borrowing as necessary. However, a fixed cap on Treasury borrowing exists separately–a debt limit or debt ceiling. This means that while the government is legally mandated to pay contractors who have fulfilled their contracts, compensate its personnel, address Medicare expenses, disburse compensation to disabled veterans, fulfill interest obligations on outstanding debt, and more — the Treasury will be prohibited from borrowing to fulfill these obligations. To avert this conflict of legal obligations, Congress consistently resolves the issue by elevating the debt limit to a fresh monetary threshold or by temporarily suspending the debt limit for a designated duration. This approach prevents the Treasury from breaching contracts and violating the nation’s budgetary regulations through illegal default. However, the deliberation over legislation to heighten the debt limit can be contentious and time-consuming, potentially casting a shadow over the economy due to the looming threat of a potential government default, until the debt limit is eventually elevated or suspended.

The norm of applying the rules and procedures of the Congressional Budget Act on an annual basis has largely broken down. For the last decade or more, Congress has rarely followed the Act’s orderly process. Deadlines are routinely missed. Perhaps most importantly, Congress has sought to adopt a budget resolution mainly when it has chosen to create a reconciliation bill, which is not subject to a Senate filibuster. Nevertheless, the Act’s rules and procedures can still shape and influence consideration of fiscal policy in Congress, and to a significant degree the reconciliation process is used to enact major legislation.

State Government Budgetary Processes

The budgetary process at the state level in the United States is somewhat similar to the federal process but varies quite a bit from state to state. Generally, the process begins with the governor proposing a budget to the state legislature, which includes estimates of revenue and spending, as well as proposed funding for various government agencies and programs.

The legislature then reviews the governor’s budget proposal and creates its own budget, which sets overall spending and revenue targets for the coming fiscal year. The budget is then allocated to various government agencies and programs through appropriations bills, which must be passed by the legislature and signed into law by the governor.

States assume a significant role in executing federal programs and determining the utilization of federal funds, apart from disbursing their own resources. For instance, they formulate the framework for health services dispensed through Medicaid and decide where to channel federal funds for highways and public transportation, both of which require state contributions. Moreover, state budgets serve as conduits for disbursing funds that aid local communities, spanning domains from housing to healthcare to public safety.

Budgets possess the potential to transform and safeguard lives. The priorities of a state are unveiled through its budgetary allocations. State budgets hold a pivotal position in addressing the needs of residents and fostering prospects for the advancement of families and communities. These budgets also possess the ability to ameliorate long standing racial and economic disparities in access to education, housing, and employment. Many proponents assert that a budget embodies moral principles. This underscores the fact that every individual is vested in the outcomes derived from state budget deliberations.

Each year, or every other year in states adopting a biennial budget, a state’s budget is ratified. This budgetary procedure typically unfolds during the legislative session of most states, commencing in January. The initiation of this process occurs as the governor presents a preliminary budget proposal, which, in certain states, transpires prior to the commencement of the legislative session. Subsequently, the process advances to the legislature, wielding substantial influence over the definitive shape of the budget.

Over a span of several months, lawmakers meticulously scrutinize and adjust the governor’s proposition, appending additional tax and expenditure measures in alignment with their assessment. Throughout this journey, all states facilitate public participation in the budgeting process, allowing individuals to contribute their perspectives on budgetary priorities.

Types of Budgets

There are two fundamental categories of budgets. The most prevalent, and the one that immediately comes to mind for most individuals when discussing budgets, is referred to as the operating budget. This constitutes a short-term strategy for effectively managing the resources required to execute a program. The term “short-term” can encompass a span ranging from several weeks to a few years. Typically, an operating budget is formulated for each fiscal year, subject to adjustments as circumstances dictate.

The second type is the capital budget process, which is concerned with strategic planning for significant outlays involving capital items. Capital expenses should target enduring investments (such as buildings and bridges) that yield returns for numerous years after their completion. Capital budgets generally encompass periods of 5 to 10 years and undergo annual revisions. The inclusions in capital budgets can be financed via avenues such as borrowing (including tax-exempt municipal bonds), savings, grants, revenue sharing, special assessments, and the like. A capital budget facilitates the separation of the funding for capital or investment outlays from ongoing or operating expenses. In contrast, the federal government doesn’t adhere to a capital budget approach in the sense of isolating the financing of capital initiatives from ongoing expenditures.

Incrementalism

Incrementalism is a budgeting approach characterized by its gradual and incremental adjustments to existing financial allocations. In this method, budget decisions are based on historical patterns and precedents, where the current year’s budget serves as the starting point for the next budget cycle. Adjustments are typically made by adding or subtracting a certain percentage to each line item or department’s previous allocation. This approach is often favored for its simplicity and stability, as it avoids significant deviations from established spending levels.

One of the key advantages of incremental budgeting is its ability to provide a sense of stability and predictability in financial planning. Organizations that utilize incrementalism can maintain continuity in their operations, as they build upon prior budget allocations and avoid abrupt shifts in resource distribution. This stability can be particularly useful in government agencies and large organizations, where sudden budget changes could disrupt essential services or programs. Additionally, incrementalism simplifies the budgeting process by reducing the need for extensive reevaluation of every expenditure each budget cycle, which can save time and resources

However, critics of incrementalism argue that this approach may lead to inefficiencies and suboptimal resource allocation. The reliance on historical data and past practices might prevent organizations from adapting to changing circumstances or shifting priorities. It can perpetuate ineffective or outdated programs simply because they have been funded in the past. Critics also contend that incremental budgeting might discourage innovation and the pursuit of new initiatives, as resources are primarily allocated based on what has been done before rather than what might yield the greatest impact in the future. As a result, many organizations opt for a combination of incremental budgeting and other approaches, such as performance-based budgeting, to strike a balance between stability and strategic resource allocation.

Line-Item Budgets

Line-item budgeting is a traditional and widely utilized method of budgeting that breaks down financial allocations into distinct line items, each representing a specific expense category. In this approach, the budget is structured with detailed lists of individual expenses, typically categorized by department, program, or activity. Each line item is associated with a specific monetary value, providing a clear breakdown of how funds will be allocated across various components of an organization’s operations.

One of the key characteristics of line-item budgeting is its emphasis on simplicity and transparency. By categorizing expenditures into easily identifiable line items, decision- makers can readily discern where funds are allocated and how resources are distributed within an organization. This level of clarity makes line-item budgeting particularly well- suited for tracking expenses and facilitating accountability. Moreover, since line-item budgets provide a historical record of spending patterns, they can aid in making informed decisions during subsequent budget cycles.

While line-item budgeting offers simplicity and transparency, it does have limitations. Critics argue that this method might lack strategic focus, as it prioritizes tracking individual expenses rather than evaluating the alignment of budget allocations with overarching goals and priorities. It can potentially hinder innovation and flexibility, as it may be challenging to reallocate funds between line items to respond to changing needs. Additionally, the granularity of line-item budgets can make it difficult to ascertain the impact of funding decisions on broader organizational objectives. As a result, some organizations have transitioned to more modern budgeting approaches that offer greater strategic alignment and performance evaluation while still retaining the transparency aspects of line-item budgeting.

Performance Budgets

Performance budgeting is a budgeting approach that focuses on linking financial allocations to the outcomes and results that an organization aims to achieve. Unlike traditional budgeting methods that emphasize inputs and expenditures, performance budgeting places a strong emphasis on the effectiveness and efficiency of programs and projects. In this approach, budget decisions are based on the anticipated performance metrics, goals, and targets, aligning funding with the achievement of specific outcomes.

One of the key features of performance budgeting is its emphasis on measuring and evaluating the impact of budget allocations. Organizations that adopt performance budgeting establish clear performance indicators and benchmarks for each program or project. These indicators enable decision-makers to assess the success of initiatives based on their ability to meet predetermined objectives. By holding programs accountable for their performance, this approach promotes transparency and accountability in resource allocation, as well as the optimization of resources toward the most effective activities.

However, implementing performance budgeting can be complex and challenging. Establishing accurate performance metrics, measuring outcomes, and attributing results solely to budget decisions can be difficult, especially for programs with long-term or indirect impacts. Additionally, performance budgeting requires a shift in organizational culture, as it encourages a results-oriented mindset and necessitates the collection and analysis of performance data. Despite these challenges, many organizations, including government agencies, non-profits, and businesses, have embraced performance budgeting as a way to enhance their decision-making, ensure resource efficiency, and achieve their intended outcomes more effectively.

Zero-Based Budgets

Zero-based budgeting (ZBB) is a budgeting methodology that stands in contrast to traditional budgeting approaches. In ZBB, every budget cycle starts from scratch, requiring managers and departments to justify all expenses as if they were starting anew, regardless of whether they were previously approved. This approach challenges the assumption that previous budgets are automatically valid for the upcoming period, encouraging a thorough review of each expenditure and activity. ZBB emphasizes the need for a clear rationale for spending and allocates resources based on the merits and priorities of each program.

One of the primary advantages of zero-based budgeting is its ability to promote efficiency and resource optimization. By requiring each expenditure to be justified and evaluated, ZBB helps identify redundancies, inefficiencies, and outdated practices that might have been perpetuated through traditional incremental budgeting. This encourages managers to critically assess the necessity of each program or activity and prioritize those that offer the greatest value and impact. ZBB also provides a platform for reallocating resources from underperforming or less relevant areas to initiatives that are more aligned with organizational objectives.

However, zero-based budgeting is not without challenges. Implementing ZBB demands substantial time and effort, particularly during the initial transition period, as managers need to thoroughly evaluate and justify each expenditure. The process can be resource-intensive and may require specialized training for staff involved in the budgeting process. Additionally, ZBB might lead to short-term decision-making, as managers could focus on easily quantifiable short-term benefits rather than long-term strategic considerations. Despite these challenges, organizations that adopt zero-based budgeting often value its capacity to streamline operations, increase accountability, and foster a culture of financial responsibility and efficiency.

Performance Results Budgets

Performance results budgeting, also known as outcomes-based budgeting, is an advanced budgeting approach that places a strong emphasis on linking budget allocations to the desired outcomes and results of programs and projects. Unlike traditional budgeting methods that focus primarily on inputs and expenditures, performance results budgeting centers on measuring the impact and effectiveness of budget allocations in achieving specific goals. In this approach, budgets are designed to align financial resources with the intended outcomes, ensuring that funding is directed towards activities that contribute directly to positive results.

The core principle of performance results budgeting is to measure success based on achieved outcomes rather than simply tracking spending. This requires organizations to establish clear and measurable performance indicators for each program or project. These indicators enable decision-makers to assess the extent to which budgeted resources have contributed to the intended results. By providing a direct link between funding and outcomes, performance results budgeting fosters transparency, accountability, and informed decision-making. It also encourages a focus on continuous improvement, as programs are evaluated based on their ability to deliver meaningful results.

Implementing performance results budgeting requires a comprehensive shift in organizational culture and practices. Organizations need to establish a robust system for tracking and measuring outcomes, as well as collecting relevant data to evaluate the effectiveness of their initiatives. This approach promotes a results-oriented mindset throughout the organization, encouraging departments and managers to identify strategies that yield the highest impact and allocate resources accordingly. While the adoption of performance results budgeting can be challenging due to its data-driven and accountability-focused nature, many organizations consider it a valuable tool for maximizing the value of their budgets, enhancing program effectiveness, and aligning their activities with strategic objectives.

Financing the Public Sector

Governments possess a set of eight fundamental approaches to secure the funds needed for their expenditure obligations. This marks a significant progression from ancient times, when revenue primarily stemmed from tax collectors and the compulsory confiscation of assets. In the contemporary landscape, governments are tasked with selecting from the subsequent alternatives:

- Levying a direct tax

- Indirect taxation

- User charges and fees

- Grants

- Profits from activities/enterprises

- Borrowing from public (bonds) or private (loans)

- Public-private partnership, franchises, licensing agreements

- Interest earnings

Each of these strategies for generating government revenue entails intricate policy considerations, encompassing factors such as which demographic bears the tax burden, whether a method will successfully produce the anticipated revenue, equity of distribution, and the feasibility and cost of administration. Should these financing avenues prove insufficient, governments might explore privatization, expenditure reduction, or program discontinuation as means to curtail the scope of necessary financial commitments.

Taxation

The history of taxation dates back to ancient civilizations, where early forms of taxation were employed to fund public infrastructure and services. One of the earliest known instances of taxation was in ancient Egypt, where pharaohs collected taxes in the form of goods and labor to support construction projects such as the pyramids. Similarly, in ancient Mesopotamia, taxes were levied to support the maintenance of irrigation systems and the provision of defense.

As societies evolved, so did the methods and purposes of taxation. In ancient Rome, taxes played a crucial role in funding the expansive Roman Empire. The Romans levied various types of taxes, including property taxes, sales taxes, and import/export duties. The administrative sophistication of the Roman tax system allowed them to collect revenue efficiently from their vast territories.

During the medieval period, feudal systems emerged in Europe, where peasants paid a portion of their agricultural produce to feudal lords in exchange for protection and use of land. However, the establishment of more centralized nation-states marked a turning point in taxation. In the 17th and 18th centuries, monarchs and governments began to assert more control over taxation to finance wars and build modern bureaucracies. This period saw the emergence of concepts like the social contract, where citizens consented to taxation in exchange for the protection and services provided by the state.

The Industrial Revolution brought about significant economic changes, leading to the implementation of new forms of taxation to support the growing needs of modern societies. Income taxes became more prominent, as governments sought to generate revenue from the increasingly urban and diverse workforce. The 20th century saw further developments, including the introduction of progressive taxation to address income inequality, as well as the establishment of social welfare programs funded through taxation. Today, taxation continues to play a vital role in shaping economies and societies, funding public services, infrastructure, and addressing various social and economic challenges.

Significant developments in the history of taxation in the United States:

1765: The Stamp Act is enacted by the British Parliament, imposing taxes on various paper goods and legal documents in the American colonies. This sparks widespread protests and resistance from colonists who argue against “taxation without representation.”

1773: The Boston Tea Party takes place as American colonists, in protest of the British-imposed tea tax, throw chests of tea into Boston Harbor.

1787: The U.S. Constitution is ratified, granting Congress the power to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises.”

1791: The first federal excise tax is levied on distilled spirits, sparking the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania in protest against the tax.

1861-1865: The Civil War prompts the implementation of various taxes, including the first federal income tax in 1861, to fund the war effort. The income tax is repealed in 1872.

1913: The 16th Amendment to the Constitution is ratified, establishing the federal income tax as a permanent part of the U.S. tax system.

1935: The Social Security Act is passed, introducing the payroll tax to fund social welfare programs.

1942: The Revenue Act of 1942 introduces automatic payroll withholding for income taxes, making tax collection more efficient.

1965: Medicare and Medicaid are established, leading to payroll tax increases to support these healthcare programs.

1981: The Economic Recovery Tax Act is enacted, implementing significant tax cuts under President Ronald Reagan.

1986: The Tax Reform Act is passed, simplifying the tax code and eliminating many deductions while reducing tax rates.

1990: President George H.W. Bush signs a budget deal that includes tax increases, going against his “Read my lips, no new taxes” pledge.

2001: The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act is signed into law, introducing tax cuts under President George W. Bush.

2010: The Affordable Care Act is passed, introducing various taxes to fund healthcare reforms, including the Net Investment Income Tax and the Additional Medicare Tax.

2017: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is enacted, implementing significant tax cuts and changes to the tax code under President Donald Trump.

Please note that this timeline highlights key developments, and there are many more nuanced changes and legislative actions related to taxation in the U.S. throughout its history.

Taxation stands as one of the most volatile subjects in the realm of politics. A poignant example of its influence is found in Walter Mondale’s acceptance of the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination back in 1984. During his address, Mondale candidly stated, “Taxes will experience an increase, and anyone asserting otherwise is not being truthful.” Despite his forthrightness, he suffered a resounding defeat. In stark contrast, George Bush, upon embracing the Republican Party’s presidential nomination in 1988, emphatically declared, “Read my words, no novel taxes!” His triumph was decisive. Nonetheless, Bush’s assurances turned out to be far from accurate, as he ultimately implemented tax hikes. This decision significantly contributed to his electoral struggles during his unsuccessful reelection bid in 1992. The tale serves as a notable lesson in the intricate dynamics of political pledges and the ramifications they can bear.

Progressive, Regressive and Flat Taxes

Progressive taxation is a fundamental concept in the realm of taxation that involves imposing higher tax rates on individuals or entities with higher incomes or wealth. The principle behind progressive taxation is rooted in the idea of income redistribution and social equity. Under this system, as a person’s income rises, the proportion of their income paid in taxes also increases. This approach is often seen as a way to address income inequality by placing a heavier burden on those who can afford it more, while providing relief to lower-income individuals.

One of the key benefits of progressive taxation is its potential to reduce economic disparities within a society. By taxing higher income earners at higher rates, governments can generate revenue that can be used to fund social programs, infrastructure, and public services that benefit a broader segment of the population. This approach aligns with the principle of addressing the needs of marginalized and vulnerable individuals, as it directs resources toward initiatives that improve overall societal well-being.

However, progressive taxation is not without its critics. Opponents argue that excessively high tax rates on the wealthy can discourage investment, innovation, and economic growth. Detractors also raise concerns about potential tax evasion strategies that could emerge as a response to steeply progressive tax systems. Striking the right balance between revenue generation, social equity, and economic growth is a complex challenge that requires careful consideration of a country’s economic conditions and policy objectives. Despite the ongoing debate, progressive taxation remains a central component of many countries’ tax systems as they seek to create a fairer and more inclusive society.

Regressive taxation is a taxation model where the tax burden disproportionately affects individuals or entities with lower incomes or fewer resources. Unlike progressive taxation, where tax rates increase as income rises, regressive taxation involves a higher proportion of income being taken as taxes from those with lower earnings. This can result in a more significant impact on individuals who are already economically disadvantaged. Progressive taxation is implemented on purpose–people with more money will have more left over, even if they pay higher tax rates. Conversely, regressive taxation is something that tends to happen more as a side effect. One common example of a regressive tax is sales tax. Imagine this, you are a broke college student with $20 to your name and you head into a coffee shop to buy a $5 coffee. Say the sales tax where you are (for nice, round numbers) is 10%. You pay $5.50 for your coffee and you have $14.50 left over. That $.50 was 2.5% of the money you’d had. Now imagine that Warren Buffet also goes to buy coffee. He chooses the same coffee and spends the same $5.50 you did. Because Mr. Buffett is worth around $120B today, that $.50 represents about .000000000417% of the money he has. That sales tax was a larger burden on you than it was on him.

One notable characteristic of regressive taxation is its potential to exacerbate income inequality. As lower-income individuals spend a larger portion of their income on goods and services subject to regressive taxes, these taxes effectively take a greater share of their available resources. This dynamic contrasts with progressive taxation, which seeks to distribute the tax burden more equitably based on income levels. Critics argue that regressive taxation can perpetuate cycles of poverty and hinder social mobility by placing a heavier financial strain on those who are least able to bear it.

While regressive taxes can be seen as inequitable, proponents argue that certain consumption-based taxes are simple to administer and can encourage responsible spending. In some cases, regressive taxes may be combined with targeted social programs to mitigate their regressive effects, such as providing subsidies or exemptions for essential goods and services. Balancing the revenue needs of governments with the goal of reducing income inequality is a central challenge in designing tax systems that promote economic fairness and societal well-being.

Because of how some see the benefits of things like consumption taxes, within certain political circles there are frequent calls to institute a “flat tax.” The flat tax, often referred to as a proportional tax, is a taxation system in which all individuals or entities are taxed at the same fixed percentage rate, regardless of their income level. This system aims to simplify the tax code by applying a uniform tax rate to all taxpayers. Proponents of the flat tax argue that it eliminates the complexity and loopholes associated with progressive tax systems, leading to increased transparency and ease of compliance. Additionally, they believe that a flat tax can encourage economic growth by providing individuals and businesses with greater certainty and predictability regarding their tax liabilities.

Critics, however, highlight the same potential fairness concerns with the flat tax as discussed above with the regressive taxes. Since everyone pays the same percentage of their income, regardless of whether they’re low, middle, or high-income earners, critics argue that this approach places a heavier burden on lower-income individuals. The regressive nature of the flat tax can exacerbate income inequality by disproportionately affecting those with less disposable income. Critics also raise concerns about potential revenue shortfalls, as the wealthy may pay lower effective tax rates compared to progressive systems where higher earners are taxed at higher rates.

Implementing a flat tax system involves careful consideration of both economic and social implications. While proponents emphasize its simplicity and potential economic benefits, critics underline the potential for increased inequality. Finding a balance between maintaining revenue levels, promoting fairness, and stimulating economic growth remains a key challenge in shaping tax policy decisions related to the flat tax.

User Fees and Charges

Governments raise money through user fees by charging individuals or entities for specific government services or facilities they directly use or benefit from. User fees are a form of revenue generation that allows governments to recover some of the costs associated with providing these services without relying solely on general taxation. This approach is often seen as equitable since it ensures that those who directly benefit from a particular service or resource contribute to its upkeep and maintenance. User fees can cover a wide range of services, such as tolls for using highways, entrance fees for national parks, tuition fees for public universities, and charges for government-provided licenses or permits.

The implementation of user fees requires careful consideration of various factors. Governments need to strike a balance between ensuring that essential services remain accessible to all citizens while also generating sufficient revenue to cover costs. There is also the challenge of avoiding potential inequities, as user fees can disproportionately affect lower-income individuals who may find it difficult to afford these additional expenses. Striking the right balance often involves providing exemptions, discounts, or subsidies to vulnerable populations to mitigate these regressive effects. Overall, user fees can offer a valuable revenue stream for governments while allowing for a more direct connection between the cost of services and the individuals benefiting from them.

Grants

Governments raise money by obtaining grants, which are financial contributions provided by external entities, such as other governments, international organizations, foundations, or private corporations. Grants serve as a means for governments to secure additional funds without resorting to traditional forms of taxation or borrowing. These funds can be directed towards specific projects, programs, or initiatives aligned with the objectives of the grant-giving organization. Grants are often used to support diverse areas such as infrastructure development, healthcare initiatives, education programs, research projects, and social welfare programs.

Obtaining grants requires governments to present well-structured proposals that outline the intended use of funds, the projected outcomes, and the alignment with the grantor’s goals. The process can be competitive, with governments competing against other applicants for limited funding opportunities. Successful grant applications often highlight the potential impact of the proposed project on the community or society as a whole.

While grants provide a valuable source of additional revenue, governments must also consider the conditions and requirements attached to the funds. These conditions can range from strict reporting and accountability measures to mandates regarding the use of funds for specific purposes. Balancing the benefits of grant funding with the need to maintain sovereignty and address local priorities remains a critical aspect of government grant-seeking strategies.

Profits

Governments can generate profits from certain enterprises by engaging in activities that yield revenue beyond the costs of operation. These government-owned or operated ventures, often referred to as public enterprises or state-owned enterprises (SOEs), can encompass a wide range of sectors, including energy, telecommunications, transportation, and more. By effectively managing and strategically investing in these enterprises, governments can not only provide essential services to citizens but also generate income that can be channeled back into public programs and infrastructure development.

To make a profit from public enterprises, governments must adopt effective management practices, ensure operational efficiency, and consider market dynamics. Competing in sectors with private businesses requires governments to maintain high standards of service and innovation to attract customers and clients. However, it’s crucial to strike a balance between profitability and the broader public interest. Some governments choose to subsidize certain enterprises, such as public transportation, to ensure affordability and accessibility for citizens while focusing on profit generation in areas where market dynamics allow. Careful monitoring, transparent governance, and accountability mechanisms are essential to prevent inefficiencies and maintain public trust in these profit-generating government enterprises.

Borrowing

Governments can raise money through borrowing by issuing debt securities in the form of government bonds. When a government needs to finance a budget deficit or fund specific projects, it can borrow funds from investors by selling these bonds. Investors purchase government bonds with the expectation of receiving the principal amount plus interest over a predetermined period. This borrowing mechanism allows governments to access capital without immediately increasing taxes or cutting spending, and the borrowed funds can be used for various purposes such as infrastructure development, public services, or economic stimulus.

The process of government borrowing involves careful consideration of factors such as interest rates, maturity periods, and investor confidence. The government’s creditworthiness and ability to repay debt play a crucial role in determining the terms of borrowing. Governments with strong fiscal discipline and stable economies tend to enjoy lower borrowing costs, as investors perceive them as less risky. Additionally, the central bank’s monetary policy can impact interest rates, affecting the government’s cost of borrowing. While borrowing can provide necessary funds, governments must also be vigilant about managing their debt levels to avoid excessive interest payments and potential negative effects on economic stability.

Governments have several options when issuing debt, including short-term and long- term bonds, as well as bonds with fixed or variable interest rates. By effectively managing their borrowing strategies and adhering to responsible fiscal policies, governments can leverage borrowing as a tool for financing critical initiatives and addressing economic challenges. However, excessive reliance on borrowing can lead to unsustainable debt levels and potential economic instability, underscoring the importance of prudent debt management and long-term financial planning.

Public-Private Partnerships

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are collaborative arrangements between government entities and private sector companies to jointly plan, develop, and operate projects or services that serve the public interest. These partnerships leverage the strengths of both sectors, combining the public sector’s regulatory and financing capacities with the private sector’s expertise in project management, innovation, and operational efficiency. PPPs can encompass a wide range of initiatives, including infrastructure projects like roads, bridges, and airports, as well as public services like healthcare, education, and utilities. The primary goal of PPPs is to deliver improved services or infrastructure while optimizing resource allocation and risk sharing.