Chapter 12: Remix Research for a Public Audience

Kat Gray; Ann Fillmore; and Melanie Gagich

Introduction

In addition to your grant proposal, Project 4 asks you to create a multimodal remix of your research materials that you could present to your audience of stakeholders. This means that you will think beyond presenting your research to fellow experts or people within the same organization. Instead, you will need to think about how to communicate your expert research to an audience with stakes in the game – the very people who will benefit from your project, if it is implemented.

In this chapter, you will learn about the considerations of presenting to a public audience and how this work changes when you think about how to share your research with nonexpert audiences. Then, you’ll learn principles of multimodal design and a design process for your group for the multimodal remix.

Communicating Research to a Public Audience

To begin thinking about communicating with a public audience, it is important to understand what the term public means. In many ways, it is more easy to define what a public audience is not: it is not a highly educated, specialized audience (like academics, or subject matter experts working within organizations or corporations); it is not an audience within an organization (like a project team inside a company, or a manager, boss, or shareholder). A general public audience, then, is an audience without specialized knowledge in a topic – they haven’t read the research, done the experiments, or gotten education in a particular field. However, that doesn’t mean such an audience has no interest in research. Think of the ways that you hear about research in daily life – you might hear from the news or social media that a study shows a certain food to be high in cholesterol, or that research can show you the most effective way to train to run a marathon.

Jerry Plotnick (2017) argued that public writing “aims to be accessible” and “relevant.” In service of these aims, public writing takes a wide variety of forms, depending on the needs of the audience, the context of communication, and the reasons the writer wants to write. Public writing is a “broad category that includes a wide variety of genres: opinion pieces, letters to the editor, blogs, newspaper reports, magazine features, letters to elected officials, memoirs, obituaries, and much more” (Plotnick, 2017). Public writing is a powerful tool to extend research into new spaces, but, like all other types of writing, it takes careful thought and planning.

Academic vs. Public Audiences

Since you are already familiar with academic writing, it may be helpful to define more clearly the differences between academic and public audiences. Doing so will help you to understand how to move from the more formal style of your problem primer and grant proposal and into a style more suited for communication with public audiences.

To people outside an academic audience, academic writing can seem hard to understand and full of jargon; written in such a way, it’s hard for public audiences to understand why academic writing is important. Public writing offers an opportunity for people writing from the academic (or expert) world to communicate their knowledge in new ways, for new purposes. As Jenn McClearen (2023) wrote, deciding which register is most appropriate for your writing means “figur[ing] out who our audiences are in order to determine which style is best for them.”

Academic writing, said McClearen (2023), “speaks to very specific audiences” in a particular scholarly field or discipline. Academic writing is a process of “citing previous conversations in the literature and connecting our ideas to theirs” (McClearen, 2023). That is, the work of academic writing is about knowledge creation of a very particular kind. It is written the way it is because the specialized vocabulary used by academics “ensures that ideas are communicated to a specialized audience with the utmost clarity and accuracy” (McClearen, 2023). Academic writing, then, is writing that specifically caters to expert audiences with a lot of education and experience in a field. The choices academic writers make reflect that reality.

Public writing, on the other hand, “uses a language that everyone understands” (McClearen, 2023). Scholars want to write for the public because it gives them an opportunity to “disseminat[e] knowledge, engag[e] communities, and advocat[e] for evidence-based policies” thus “ensuring that their research has real-world relevance and promotes positive social change” (McClearen, 2023). Public writing, in other words, lets carefully conducted expert research have an influence on the world around us. Kelly Baker, an academic engaged in public writing since 2007, characterized public audiences as “smart, but not specialists” (n.d.). However, she wrote, “audiences aren’t static,” and this means that “[w]riting for a public audience can mean vastly different things depending on who you want your audience to be and where you publish” (Baker, n.d.). As with any rhetorical situation, a careful analysis of your audience (or desired audience) can help you find the right genre, style, and tone.

Talking to Publics

When you present research to a public audience, you will want to think carefully about how you help your audience access complex research and understand what to do with that information. Jenn McClearen (2023) writes that “the accessibility of your work is relative” and has to do with “what your target audience reads,” “what writing mechanics they are used to,” and “their level of familiarity with your topic.” Once you have answers to these concerns, you can “adjust your language and tone accordingly” and create research that communicates clearly with a public audience. Knowing your audience’s expectations helps you meet them halfway.

When you create presentations for public audiences, you should keep the following tips in mind:

- Know your audience. As we will discuss below, the audience you want to reach affects the genre you choose for your presentation. Additionally, Plotnick (2017) argued, “[t]he specific genre you’re writing in will help you to form an image of your audience.” That is, genre and audience are closely related – together, they influence the choices you make about how to communicate. What do your readers know? What do they need to know? What do they want to know?

- Tell a story. Jenn McClearen (2023) reminded that presentations are an excellent opportunity to tell an engaging story about your research in ways you otherwise would not when writing for academic or professional publication. Telling stories allows writers to help a public audience understand the implications and impact of research – a story offers the ‘so what?’ that readers often search for when attempting to understand academic writing. Thinking carefully about when and how to tell stories in public presentations lets you make connections with your audience. As McClearen (2023) wrote, “[p]eople are hardwired to connect with stories.”

- Make clear and concise arguments. Writing that is clear and concise conveys an obvious meaning in as few words as needed, without compromising necessary complexity. When presenting research to the public, Kelly Baker (n.d.) wrote that you should “make your argument obvious and easy-to-follow.” This involves “being able to articulate your argument, provide evidence for it, and show readers why it matters in clear prose” (Baker, n.d.). It is your job, Baker argued, to teach your reader about your work and why it matters.

- Don’t hedge. In academic writing, it is often very important to hedge our arguments – that is, to make qualifications about what we’re going to say before we say it. Academic writing asks us to be precise, and a hedge is a rhetorical move that lets us, for example, say that while our thesis statement is true in most situations, it might be untrue under the following conditions. Academic writing builds an argument gradually, through presenting evidence. Public writers, Kelly Baker (n.d.) argued, should “tell us what you want to say in clear, precise language.”

- Use plain language. When you know your audience, you will be able to think carefully about the type of language that will help them to understand your message. Plain language, wrote McClearen (2023), usually means “avoiding the use of technical terms and academic jargon.” Instead, you should focus on paring down the length of your sentences and making your wording more direct. You can learn more about plain language at PlainLanguage.Gov.

- Set aside academic essay conventions. Because the audience is different for academic essays, academic essay conventions are not suitable for thinking through how to communicate with a public audience. For example, you don’t need a lengthy introduction when you’re talking to a public audience – you can state your point early and clearly, and move directly into your argument (Plotnick, 2017). You can use anecdotes and personal stories. You can use the words “I” and “you” to get the reader to relate more directly to your writing. Think about your rhetorical aims, and how the conventions of the genre you choose can help you meet those needs.

What is Multimodal Composition?[1]

Since you are required to produce a multimodal document explaining your research to your stakeholders, it is helpful to start this phase of the project by thinking about what “multimodal” actually means. The next section, then, discusses multimodality and modes of communication, defines important terms, and prepares you for the multimodal composition process.

What Is a Multimodal Text?

The Five Modes of Communication

Visual

The visual mode refers to what an audience can see, such as moving and still images, colors, and alphabetical text size and style. Social media photos (see Figure 1) exemplify the visual mode. The visual mode includes images, video, color, visual layout, design, font, size, formatting, symbols, visual data (charts, graphs) animations (like gifs) and more.

The visual mode helps writers communicate meaning in a way that can be seen by the audience. Sometimes people must see to believe, and visuals can be helpful and even persuasive. For example, if you want to showcase how climate change has devastated the arctic ecosystem, you might include a video that shows real-world footage, like this one by National Geographic. This video is considered a multi-modal text since words, visuals, and audio are used together for a stronger effect.

Linguistic

The linguistic mode refers to alphabetic text or spoken word. Its emphasis is on language and how words are used (verbally or written). The linguistic mode includes written and spoken words, word choice, vocabulary, grammar, structure, and the organization of sentences and paragraphs.

A traditional five paragraph essay relies on the linguistic mode; however, this mode is also apparent in some digital texts. Figure 2 shows a student’s linguistic text included in their website created to promote game-based language learning.

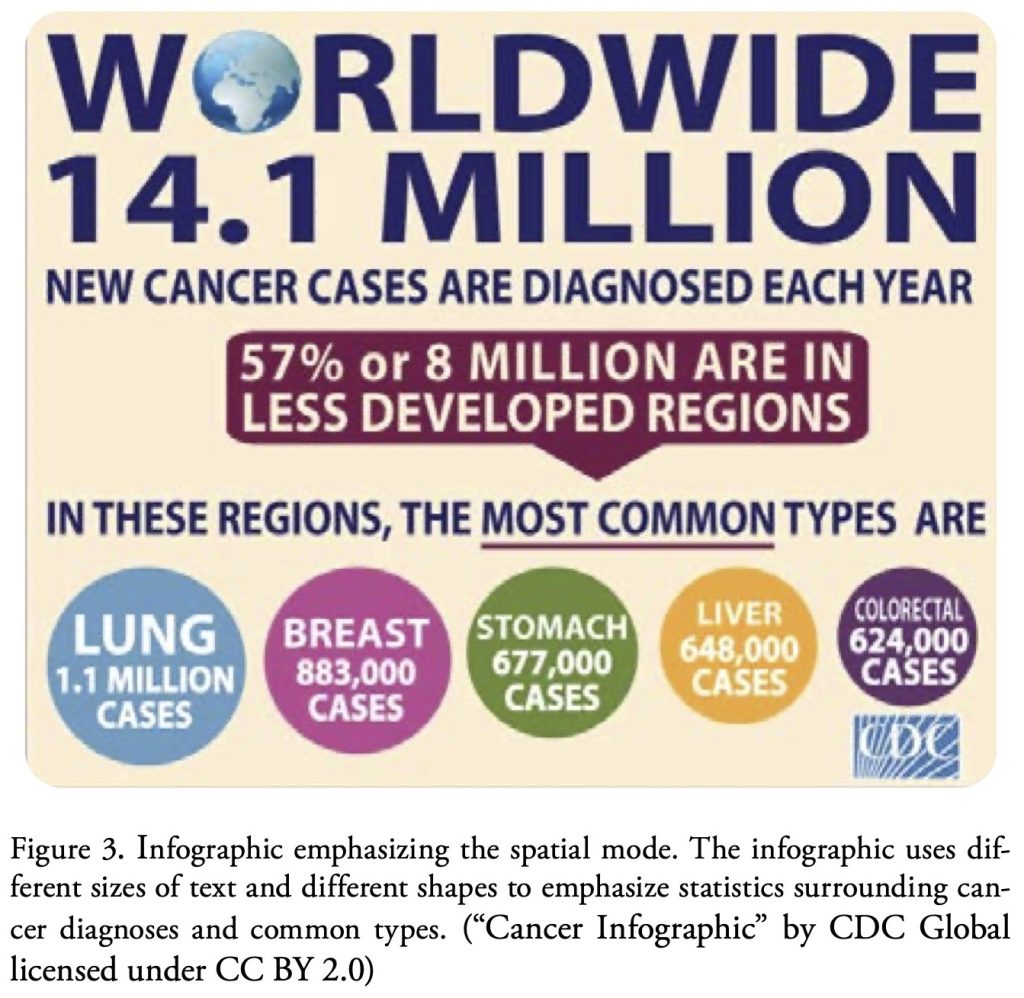

Spatial

The spatial mode refers to how a text deals with space. This also relates to how other modes are arranged, organized, emphasized, and contrasted in a text. The spatial mode includes physical arrangement: spacing, position, organization, proximity, direction, and distance between elements in a text.

Figure 3, an infographic, is an example of the spatial mode in use because it emphasizes certain percentages and words to achieve its goal. Websites also rely heavily on the spatial mode to communicate meaning. Writers make strategic rhetorical decisions about how to arrange digital information in a user-friendly way within a mobile “space.” Features like menus, headers, physical layout, and navigation tools (such as links) help the audience to interact with the site spatially.

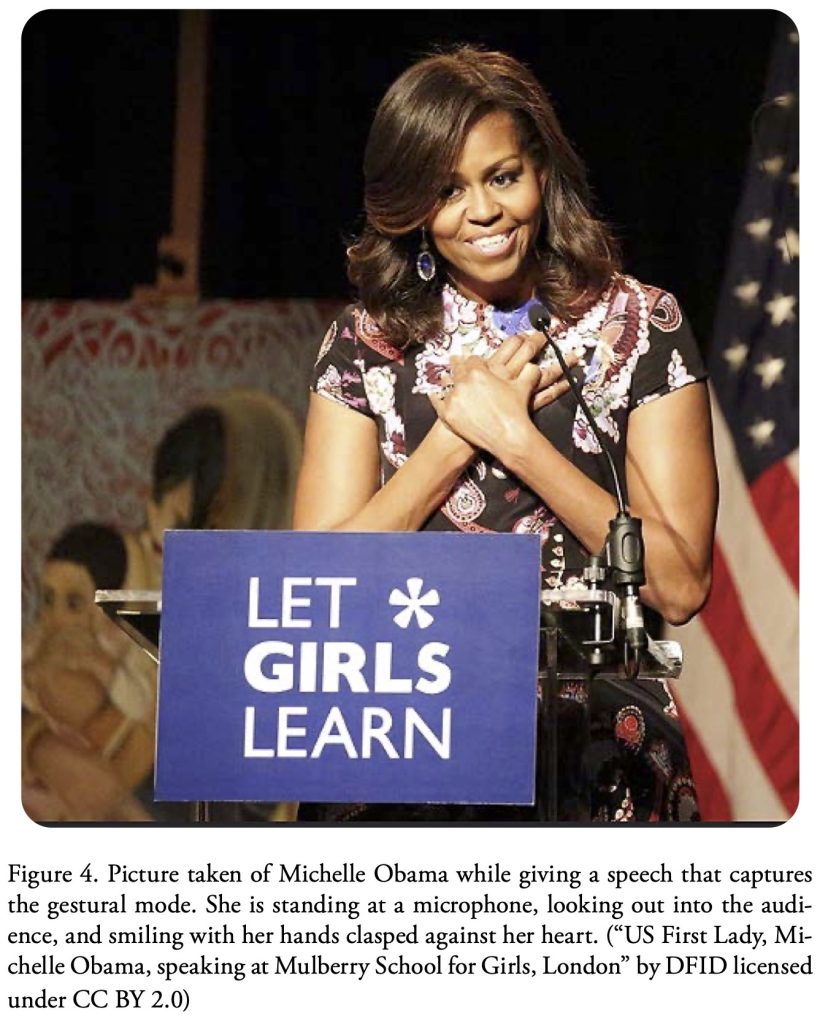

Gestural

The gestural mode refers to gesture and movement. This mode is often apparent in delivery of speeches in the way(s) that speakers move their hands and fix their facial features and in other texts that capture movement such as videos, movies, and television. The gestural mode includes movement, speed, expression, body language, facial expression, physical proximity, and interactions between people. Figure 4 shows Michelle Obama’s gestures at a speech she gave in London.

The gestural mode of communication allows writers to communicate meaning through movement. Traditionally, this mode was used in face-to-face interaction; however, modern technology allows writers to show movement virtually in their work, through video. The gestural mode is often used in combination with other modes, such as linguistic/alphabetic (written/spoken), spatial (physical arrangement), and aural (sound) to provide an enhanced sensory experience for the audience.

For example, sign languages use the gestural mode since position of the sign and movement are significant factors in generating and distinguishing meaning. In this video, look at how the speakers use movements of the hands, head, face, and body, along with position and speed, to communicate meaning to the audience. Sign languages are considered multi-modal communication since they combine linguistic/alphabetic text with movement.

Aural

The aural mode refers to what an audience member can or cannot hear. Music is the most obvious representation of the aural mode, but an absence of sound (silence) is also aural. The aural mode includes spoken words, sound, music, volume, rhythm, speed of delivery, pitch, tone of voice, and the use of silence. Examples of texts that emphasize the aural mode include podcasts, music videos, concerts, television series, movies, and radio talk shows.

Sound catches people’s attention, and writers use the aural mode to bring their words to life. For example, have you ever listened to a game on the radio? Listen to the way the sportscasters help the audience to experience the game through sound.

Designing Your Multimodal Remix[2]

A multimodal text combines various modes of communication (hence the combination of the words “multiple” and “mode” in the term “multi-modal”). Cheryl E. Ball and Colin Charlton draw from The New London Group in their argument that “[a]ny combination of modes makes a multimodal text, and all text—every piece of communication a human composes—use more than one mode. Thus, all writing is multimodal” (42). However, in some communicative texts, one mode receives more emphasis than the others. For example, academia and writing teachers have historically favored the linguistic mode, often seen in the form of the written college essay. Yet, when you communicate using an essay, you are actually using three modes of communication: linguistic, spatial, and visual. The words represent the linguistic mode (the emphasized mode), the margins and spacing characterize the spatial, and the visual mode includes elements like font, font size, or the use of bold.

Combining each mode to create a clear document often involves the writing process (i.e. invention, drafting, and revision), and a thoughtful writer will also consider how the final product does or does not address an audience. The same process is used when creating a less traditional multimodal text. For instance, when creating a text emphasizing the aural mode (e.g. a podcast), you must consider your audience, purpose, and context while also organizing and arranging your ideas and content in a coherent and logical way. This process parallels the traditional writing process.

As writers, we make choices. In every situation, we must decide how to best communicate meaning to our intended audiences. It is a process of deliberation that involves calculated choices, strategies, and moves. In the field of writing/composition, “modality” is a rhetorical decision that you need to consider as you explore how to best achieve your intended purpose(s). Below, you will learn a process for multimodal composition that you and your group can adapt to suit your project’s needs.

Creating a Multimodal Text

Now that you know what a multimodal text is, it makes sense to discuss strategies for composing a multimodal text. As with writing, multimodal composing is a process and should not only emphasize the final result. Therefore, the first three strategies listed below are pre-drafting activities.

- Determine your rhetorical situation.

- Review and analyze other multimodal texts.

- Gather content, media, and tools.

- Cite and attribute information appropriately.

- Begin drafting your text.

As with all writing processes, multimodal composition is recursive. That is, as you work on your multimodal remix, you may revisit different parts of the composing process as needed. You may start drafting, only to find that you need to go back and do more research on your rhetorical situation. The process is not linear, but iterative – more like a series of overlapping loops than a straight line.

As writers, you’ll need to determine which of the five modes could add value to your work. Be careful not to add modes just because you think you should. Each mode you use should add meaning to the text. Consider the opportunities, challenges, and constraints of any writing task and assess and revise your work to meet the needs of the audience.

Determine Your Rhetorical Situation

When brainstorming about your rhetorical situation, you should consider the purpose of your text (the message), who you want to read and interact with your text (the audience, your relationship to the message and audience (the author), the type of text you want to create (the genre), and where you want to distribute it (the medium. Descriptions of each of the five components of the rhetorical situation are offered below.

The Message

The message relates to your purpose, and you might ask yourself, what am I trying to accomplish? You should try to make the message as clear and specific as possible. Let’s say you want to create a website focused on donating to charity. An unclear message might be “getting more people in the United States to donate to charities.” A clearer message is “convincing college freshmen at my university to donate to the ASPCA” because the audience and purpose are specific rather than broad.

The Audience

There are two types of audiences. An intended audience, who you target in your message, and an unintended audience, who may stumble upon your text. When determining your message, you want to consider the beliefs, values, and demographics of your intended audience as well as the likelihood that unintended audiences will interact with your text. Using the example above, college freshmen at your university are the intended audience, and teachers, parents, and/or students from other universities represent unintended audience members. It might be helpful to approach audience using the concept of “discourse communities,” or “a group of people, members of a community, who share a common interest and who use the same language, or discourse, as they talk and write about that interest” (National Council of Teachers of English). You can read more about discourse communities in Dan Melzer’s essay, “You’ll Never Write Alone Again: Understanding Discourse Communities.”

The Author

You are the author and should consider your relationship to the message and audience. As an author, you bring explicit (obvious) and/or implicit (not obvious) biases to your message, so it is important to recognize how these might affect it and your audience. Also, you may be targeting an audience you are familiar with (perhaps you are also a college freshman) or not (perhaps you are a graduate student). It is important to think about how your familiarity with your audience might affect your message.

The Genre

Genre is a tricky term and can mean different things to different scholars, teachers, and students (Dirk 250). In the context of multimodal composing, genre refers to a type of text that has genre conventions, or audience expectations. For example, if I am creating a website (the genre), an audience would expect the following conventions: an easy-to-navigate toolbar, functional tabs, hyperlinks, and images. Yet, when thinking about genre, it is more useful to think specifically. If I am creating a website for horror film fans (the specific genre), then the audience would expect the following (more specific) genre conventions: references, images, and sounds associated with horror films, directors, actors, actresses, monsters, and villains. They would also expect color and font choices to align with the genre—it is likely that the color baby blue would not be well-received.

The Medium

While genre is the type of text you want to create, the medium refers to where you will distribute it. Classic media (plural for medium) includes distribution via radio, newspapers, magazines, and television; however, new media is defined by a text’s online distribution. Importantly, medium refers to where you will distribute your text but not how. The how refers to the technology tools you’ll use to create the text and possibly to distribute it. For example, to create a podcast, you might use your smartphone (a tool) to record, a free sound editor like Audacity (another tool) to edit it, and Soundcloud (a tool and the medium) to distribute it.

Rhetorical Situation Questions to Consider

- Does the rhetorical situation call for a certain mode? Or, do you have some creative freedom in how you present your ideas or make your argument?

- How does a certain mode affect the way your audience will receive or experience the message? What are the advantages and disadvantages of using a certain mode for this particular writing task?

- How could you combine modes? Which modes would enhance your message or help you to better get your point(s) across?

- Do you possess the technological skills necessary to effectively use a specific mode? Will you need to learn additional skills in order to create your work? If so, how can you best learn these skills in the given time frame?

Review and Analyze Other Multimodal Texts

Now that you have brainstormed your rhetorical situation and determined the type of text you want to create, it is time to begin finding other texts representative of your topic and genre. In their textbook, Writer/Designer: A Guide to Making Multimodal Projects, Arola, Sheppard, and Ball argue that “[o]ne of the best ways to begin thinking about a multimodal project is to see what has already been said about a topic you are interested in . . . as well as how other authors have designed their texts on that topic . . . ” (40). This is excellent advice. I suggest that you find at least one text you think is an exceptional example and one text you feel is lacking in some way. After you find these texts, you can conduct a brief analysis by responding to the following questions:

- What is the author’s message?

- Who are they addressing? How can you tell?

- What type of text did they create? What genre conventions do you see?

- How was the text distributed? In what ways does it relate to the target audience?

- What modes of communication are they using? Which are they emphasizing? Do these decisions support the message and/or appropriately target their audience?

- What do you like about the multimodal text?

- What, in your opinion, needs work?

If you answer these questions, you have given yourself important information to consider as you plan your own work.

Gather Content, Media, and Tools

Once you have determined your rhetorical situation and examined other multimodal texts, you should begin gathering information and materials. I have categorized this process into three components: content, visual and aural materials, and technology tools.

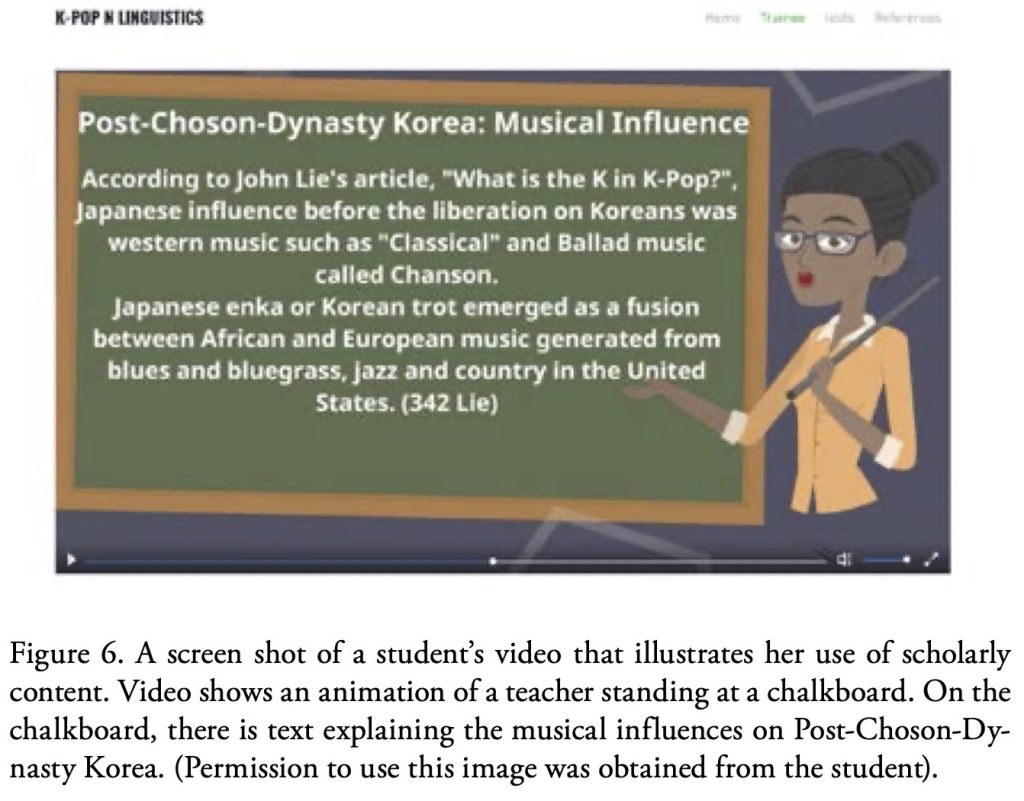

Conduct Content Research

A multimodal text should include content (pieces of information that support your message), which means you will need to conduct some research – or, ideally, use research you have already completed for your problem primer and grant proposal projects. Be sure to consult with your instructor about the types of research most suitable for your group’s project. For example, my student created a website and videos discussing the similarities between American music and K-pop (see Figure 6). Her content research includes a scholarly article from the journal World Englishes and a popular article from Billboard.com.

Collect Visual and Aural Materials

In addition to textual information, you should also collect images, sounds, videos, animations, memes, etc. you want to include in your multimodal text. For instance, Figure 6 demonstrates some of the pre-draft materials my student collected: openly licensed images of a teacher and chalkboard, a video they created using Animator, and K-Pop music to play on a loop.

Explore Openly Licensed Materials

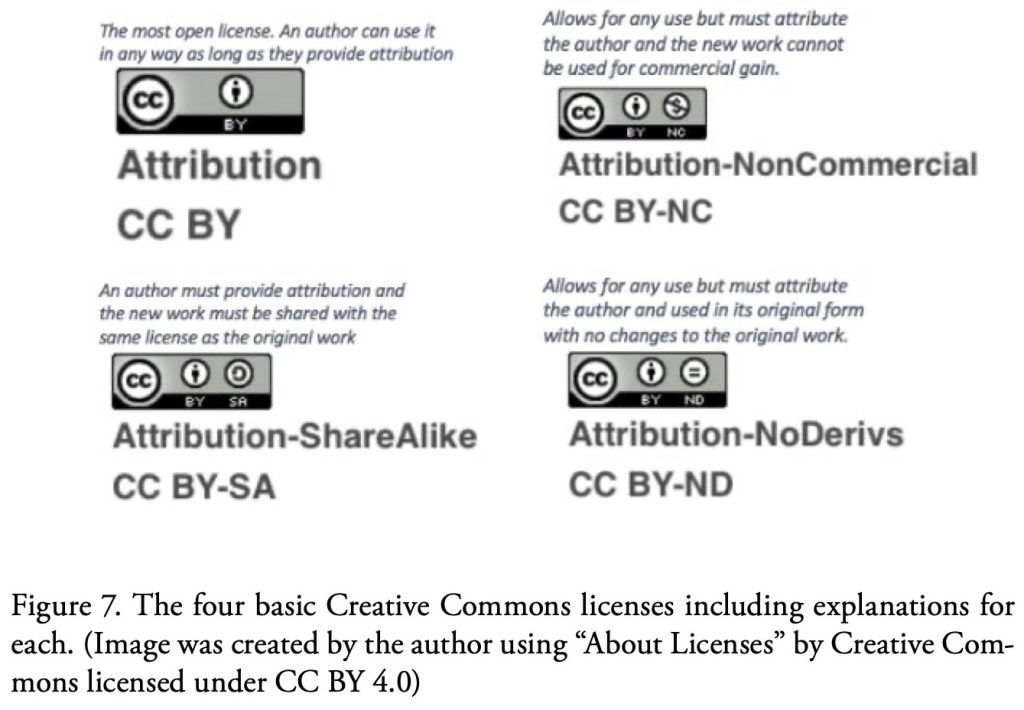

When searching for visual and aural materials, you want to consider using openly licensed materials. According to YearOfOpen.org, open licenses are “a set of conditions applied to an original work that grant permission for anyone to make use of that work as long as they follow the conditions of the license” (“What are Open Licenses”). A well-known and commonly used example of an open license are Creative Commons licenses, identified by CC. Creative Commons licenses provide the creator or author with a copyright, ensuring that they receive credit for their work, while also allowing “others to copy, distribute, and make uses of their work – at least non-commercially” (“About the Licenses”). Essentially, if a work has one of the four basic creative commons licenses (see Figure 7), then a creator/ author can use the licensed item in their own creative texts.

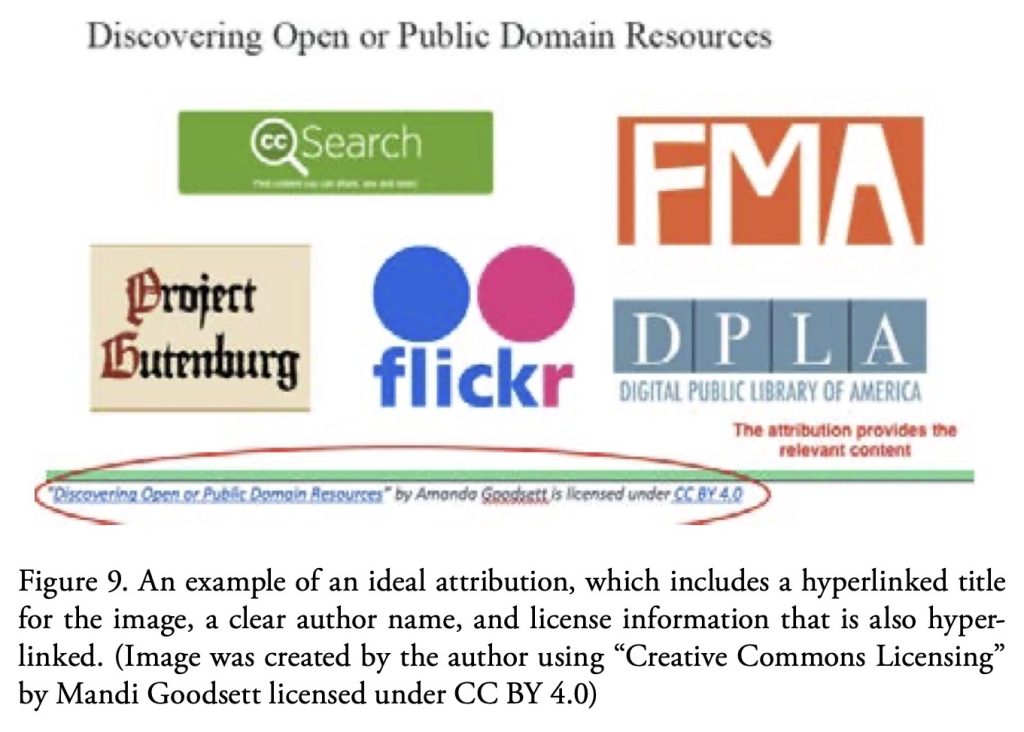

There are various websites such as CC Search, Free Music Archive (FMA), or Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) where you can find openly licensed work. You may also set filters on Flickr or Google Images to locate openly licensed work.

Collect and Evaluate Technology Tools

It is important to collect and evaluate the technology tools you need to create your multimodal text prior to drafting it. As stated previously, the technology tool helps you create the final text and might also help you distribute it. The easiest way to determine the technology tools that you need is to create a list of all of the features you want to include in your text. Once you create the list, research where to find the tools either online or at your university. Be aware that some tools may not be free (although they may come with a free trial period), but you can use software available on your computer or university computers such as iMovie or Windows Movie Maker. Or you can find freeware, software available for free online, such as Audacity (for sound editing), Canva (for infographic and/or image creation), or Blender (for video creation). Once you have created your list and found some tools, spend some time testing each one while keeping track of which is the most user-friendly and helps you achieve your composing goals.

Citing and Attributing Your Content

After researching content and collecting materials, think about how you will give rhetorically appropriate credit to authors or organizations whose work you have referenced or included. For instance, if you create a video, you should provide credits at the end rather than a Works Cited page, or if you design a website, you should include hyperlinks to outside sources rather than MLA in-text citations because this makes more sense, given the genre. For multimodal texts that rely on the aural mode (e.g. podcasts), you can use verbal attributions, or verbalize necessary information. When deciding what information is necessary, think about what you can include to help your audience locate your text, such as author, title, and website. For example, the phrase, “According to Mandi Goodsett, in her PowerPoint ‘Creative Commons Licenses’ found on the library website, a student has control over their online presence,” offers the audience key information to help them find the source.

When citing openly licensed images, videos, sounds, animations, screenshots, etc., it is important to provide an attribution. According to the CC Wiki, an appropriate attribution should include the title, author, source (hyperlinked to the original website), and license (hyperlinked to the license information). Figure 8 represents example of an inappropriate attribution and Figure 9 an ideal one.

Figure 8. An example of an inappropriate attribution that lacks title, clear author, source link, and license. (Image was created by the author using “Creative Commons Licensing” by Mandi Goodsett licensed under CC BY 4.0)

Begin Drafting Your Text

Drafting your text should include outlining or mapping your project. This could take the form of writing all of the text you want to include in an outline if you have a word-heavy multimodal text like a website, drawing your design if you are creating a poster or commercial, or writing a script if you are creating a podcast or video. Of course, you can combine any of these outlining methods or come up with your own, but thinking about what you want to do before you do it will make your final text much stronger and coherent.

Conclusion

In Project 4, you’ve been asked to communicate the results of your research project to two very different audiences: an audience of experts (the UArk Cares Foundation advisory board) and a public, nonexpert audience (your stakeholders). Thinking through how to communicate the same information to different audiences is a valuable rhetorical skill – and one that will hold you in good stead in your professional life. Regardless of the type of work you do, you will often have to communicate information about your projects to audiences with a variety of interest in and experience with your area of expertise. Communicating with a team member is different from communicating with a boss. Communicating with a boss is different from communicating with the public, through a document like a product recall. In other words, technical communicators must be adept at analyzing rhetorical situations, understanding their communication options, and making smart choices that help them communicate their message.

References

“About the Licenses.” (n.d.). CreativeCommons.org, Retrieved 18 July 2025, from https://creativecommons.org/licenses/.

Arola, Kristin L., Jennifer Sheppard, and Cheryl E. Ball. (2014). Writer/Designer: A Guide to Making Multimodal Projects. Bedford/St. Martin.

Baker, Kelly. (n.d.). Writing for a public audience. Cold takes. Retrieved 10 July 2025, from https://www.kellyjbaker.com/writing-for-a-public-audience/.

Ball, Cheryl E. and Colin Charlton. (2015). “All Writing is Multimodal.” In Naming What we Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, pp. 42-43.

CC Wiki. “Best practices for attribution.” (n.d.) Wiki.CreativeCommons.org. Retrieved 18 July 2025, from https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Best_practices_for_attribution.

Dirk, Kerry. (2010). “Navigating Genres.” WAC Clearinghouse. In Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, vol. 1, pp. 249-262. Retrieved 18 July 2025, from https://wac.colostate.edu/books/writingspaces1/dirk–navigating-genres.pdf.

Great Big Story. (2017). Spoken Without Words: Poetry with ASL Slam. YouTube. Retrieved 18 July 2025, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dmsqXwnqIw4.

Lauer, Claire. (2014). “Contending with Terms: ‘Multimodal’ and ‘Multimedia’ in the Academic and Public Spheres.” Multimodal Composition: A Critical Sourcebook, edited by Claire Lutkewitte, Bedford/St.Martin’s, pp. 22-41.

McClearen, Jenn. (2023). Academic vs public writing. Publish not perish. Retrieved 10 July 2025, from https://www.publishnotperish.net/p/academic-vs-public-writing.

McClearen, Jenn. (2023). How to write for a public audience. Publish not perish. Retrieved 10 July 2025, from https://www.publishnotperish.net/p/how-to-write-for-public-audiences.

Melzer, Dan. (2019). “You’ll Never Write Alone Again: Understanding Discourse Communities.” WAC Clearinghouse. In Writing Spaces: Readings on Writings, vol. 3. Retrieved 18 July 2025, from https://writingspaces.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/melzer-understanding-discourse-communities-1.pdf.

National Council of Teachers of English. (2012). “Discourse Community.” NCTE.org. Retrieved 18 July 2025, from https://secure.ncte.org/library/nctefiles/resources/journals/ccc/0641-sep2012/ccc0641posterdiscourse.pdf.

National Geographic. (2017). Heart-Wrenching Video: Starving Polar Bear on Iceless Land. YouTube. Retrieved 18 July, 2025 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_JhaVNJb3ag.

The New London Group. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” (1995). Harvard Educational Review, vol. 66, no.1. Retrieved 18 July 2025, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ519304.

Payson High TV. (2016). Sports Broadcast Audio Entry. YouTube. Retrieved 18 July, 2025, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GEKHVp4LTTw&.

Plotnick, Jerry. (2017). Writing for the public. University of Toronto Writing Advice. Retrieved 10 July 2025, from https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/types-of-writing/public-writing/.

Takayoshi, Pamela and Cynthia L. Selfe. (2007). “Thinking about Multimodality.” Multimodal Composition: Resources for Teachers, edited by Cynthia L. Selfe, Hampton Press, Inc., pp. 1-12.

“What are Open Licenses.” YearOfOpen.org. Retrieved 18 July 2025, from https://www.yearofopen.org/what-are-open-licenses/.

- Based on Melanie Gagich, "An Introduction to and Strategies for Multimodal Composing," in The Ask: A More Beautiful Question and Ann Fillmore, "Multi-Modal Communication: Writing in Five Modes," in Open English @SLCC. ↵

- Based on Melanie Gagich, "An Introduction to and Strategies for Multimodal Composing," in The Ask: A More Beautiful Question and Ann Fillmore, "Multi-Modal Communication: Writing in Five Modes," in Open English @SLCC. ↵