Chapter 9: Design and Run a Pilot Study

Kat Gray; Suzan Last; Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt; and Matt McKinney

Introduction

After investigating your problem with a research report in Project 3, you and your group will use the information you have collected to create a collaborative grant proposal. Proposals are another common technical writing genre, which we will review more closely in Chapter 11. A grant proposal is a type of proposal with particularly high stakes, since a grant is a monetary reward for a proposed project. Granting organizations want to see a proposal for a project that is logically planned, realistic, and well-researched.

However, before you can create a successful proposal, you need more information about your problem. In this chapter, you’ll learn about how to design a pilot study that engages ethically with your stakeholders and also helps you answer your research question. First, the chapter discusses research design ethics for projects that require human subjects research. Then, the chapter expands on three of the most common types of primary research for technical writing projects: interviews, observations, and surveys. The chapter closes with a brief discussion of the research memo you will write for this project.

Research Design Ethics[1]

Primary research is any research in which you collect raw data directly from the “real world” rather than from articles, books, or internet sources that have already collected and analyzed the data. If you are collecting data from human participants, you are engaging in “human research” and you must be aware of and follow strict ethical guidelines at your academic institution or organization. Doing this is part of your responsibility to maintain academic integrity. You can learn more about these requirements at the University of Arkansas from the Division of Research and Innovation on their page about Human Subjects Research.

In all post-secondary educational institutions, we must ensure that research involving human subjects is ethical and complies with all related laws (you can find a brief summary of those policies at the American Psychological Association’s website here). These rules are in place to protect people and communities from potential risk or harm and to ensure ethical conduct while doing research. To conduct ethical research that collects data from human subjects, you must follow all ethics requirements carefully.

Guidelines for Students Conducting Human Research

In order to adhere to the ethical requirements involved in conducting human research for your course project, you should abide by the following ethics guidelines when recruiting participants, gaining their informed consent, and managing the data you collect.

Recruiting Participants

When recruiting potential participants, you must give them the following information before you begin:

- Student researcher name(s): give your name and contact information.

- Affiliation: provide (a) the name of your institution, (b) your course name and number, and (c) your instructor’s name and contact information.

- Purpose: describe the purpose of your research (your objectives), and the benefits you hope will come from this research (overall goal). Your research should not involve any deception (e.g.: claiming to be gathering one kind of information, such as “do you prefer blue or green widgets?”, but actually gathering another kind, such as “what percentage of the population is blue/green color blind?”).

Informed Consent

You must gain the informed consent of the people you will be surveying, interviewing, or observing in non-public venues. This can be done using a consent form they can sign in person, or an “implied consent” statement on an electronic survey. The consent form should include all the information in the “recruiting” section above; in addition, you should…

- Inform participants that their participation is voluntary and that they may withdraw at any time without consequence, even if they have not completed the survey, interview, or observation process.

- Disclose any and all risk or discomfort that participation in the study may involve, and how this risk or discomfort will be addressed.

- Ensure that all participants are adults (18 years of age or older) and fully capable of giving consent; do not recruit from vulnerable or at-risk groups, and do not collect data regarding age, gender, or any other demographic information not relevant to the study (e.g.: phone numbers, medications they are taking, whether they have a criminal records, etc.).

Managing the Data

Participants should be told what will happen to the data you gather:

- In the case of surveys, the data is anonymous if you will not track who submitted which survey. In anonymous surveys, let participants know that once they submit their survey, it cannot be retrieved and removed from the overall results.

- Let survey participants know (a) that your research results will be reported without their names and identifiers, (b) where the data will be stored, (c) how it will be “published”, and (d) what will happen to the raw data once your project is complete

- Let interview participants know how their information will be used and if their names will be included or cited.

- Let observation participants know how they will be identified in the data, should they appear.

There may be additional issues that must addressed, such as accessibility and cultural considerations. If you are unsure whether a particular line of inquiry or method of data collection requires ethics approval, you should consult with your instructor about how to construct your pilot study. Most importantly, you should always be completely upfront and honest about how you are conducting your research. People participating in your research need to be reassured that you are doing this for legitimate reasons.

Stakeholder Engagement and Consultation

One important area of primary research undertaken when embarking on any large scale project entails public engagement, or stakeholder consultation. Stakeholder engagement can range from informing the public about plans for a project to engaging in consultative practices like getting input and feedback from various groups, and even to empowering key community stakeholders in the final decision-making process.

For projects that have social, economic, and environmental impacts, stakeholder consultation is a critical part of the planning stage. Creating an understanding of how projects will affect a wide variety of stakeholders is beneficial for both the company instigating the project and the people who will be affected by it. Listening to stakeholder feedback and concerns can be helpful in identifying and mitigating risks that could otherwise slow down or even derail a project. For stakeholders, the consultation process creates an opportunity to be informed, as well as to inform researchers about local contexts that may not be obvious, to raise issues and concerns, and to help shape the objectives and outcomes of the project.

What is a Stakeholder?

Stakeholders include any individual or group who may have a direct or indirect “stake” in the project – anyone who can be affected by it, or who can have an effect on the actions or decisions of the company, organization or government. They can also be people who are simply interested in the matter, but more often they are potential beneficiaries or risk-bearers. They can be internal – people from within the company or organization (owners, managers, employees, shareholders, volunteers, interns, students, etc.) – and external, such as community members or groups, investors, suppliers, consumers, policy makers, etc. Increasingly, arguments are being made for considering non-human stakeholders such as the natural environment (Driscoll and Starik 2004).

Stakeholders can contribute significantly to the decision-making and problem-solving processes. People most affected by the problem and most directly impacted by its effects can help you to

- understand the context, issues and potential impacts more fully;

- determine your focus, scope, and objectives for solutions; and

- establish whether further research is needed into the problem.

People who are attempting to solve the problem can help you

- refine, refocus, prioritize solution ideas;

- define necessary steps to achieving them; and

- implement solutions, provide key data, resources, etc.

There are also people who could help solve the problem, but lack awareness of the problem or their potential role. Consultation processes help create the awareness of the project to potentially get these people involved during the early stages of the project.

Stakeholder Mapping

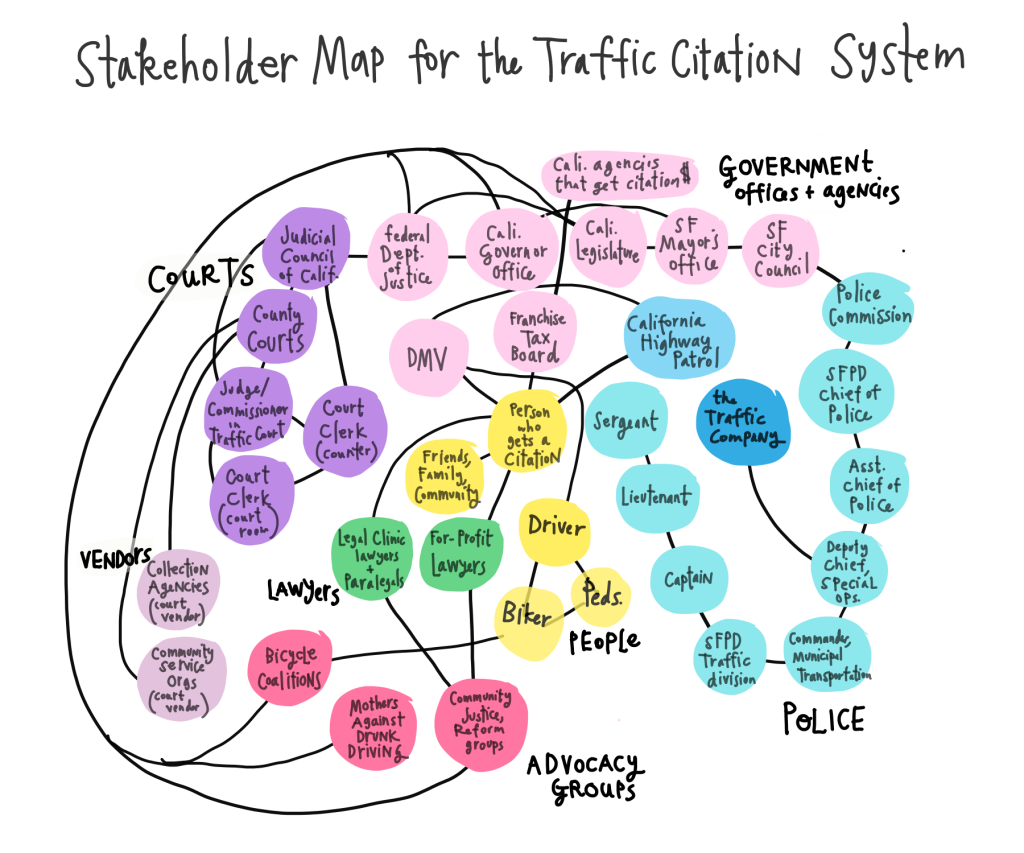

The more a stakeholder group will be materially affected by the proposed project, the more important it is for them to be identified, properly informed, and encouraged to participate in the consultation process. It is therefore critical to determine who the various stakeholders are, as well as their level of interest in the project, the potential impact it will have on them, and the power they have to shape the process and outcome. You might start by brainstorming or mind-mapping all the stakeholders you can think of. See Figure 9.1 as an example.

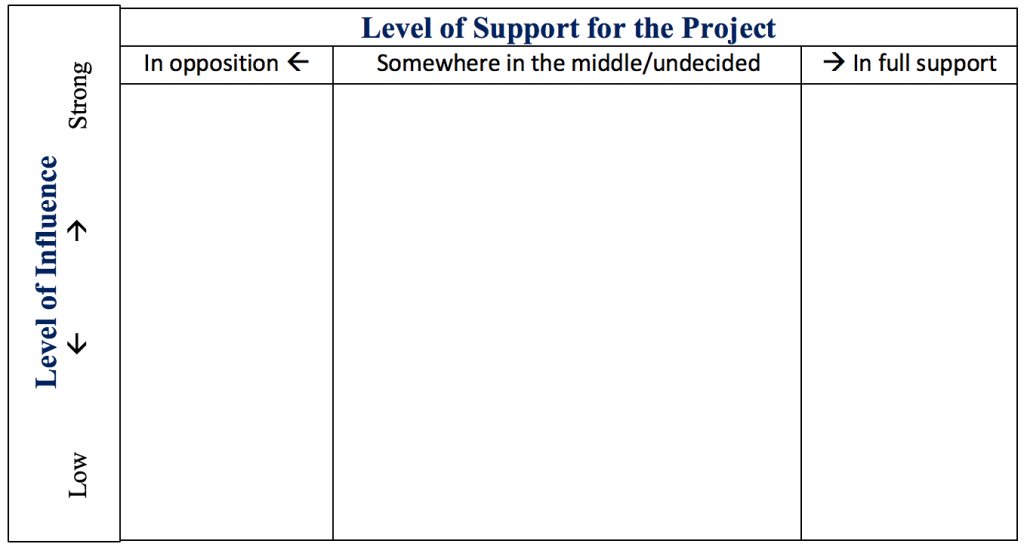

Once you have identified stakeholders who may be impacted, organize them into categories or a matrix. One standard method of organizing stakeholders is to determine which ones are likely to be in support of the project and which are likely to oppose it, and then determine how much power or influence each of those groups has (see Figure 9.2). For example, a mayor of a community has a strong level of influence. If the mayor is in full support of the project, this stakeholder would go in the top right corner of the matrix. Someone who is deeply opposed to the project, but has little influence or power, would go at the bottom left corner.

A matrix like this can help you determine what level of engagement is warranted: where efforts to consult and involve might be most needed and most effective, or where more efforts to simply inform might be most useful. You might also consider the stakeholders’ level of knowledge on the issue, level of commitment (whether in support or opposed), and resources available.

Planning Stakeholder Engagement

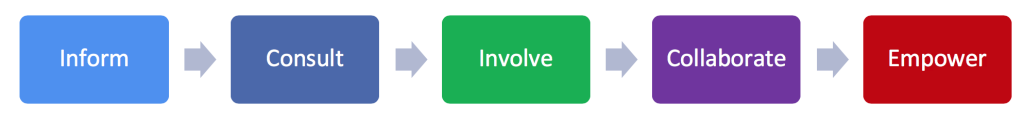

There are various levels of stakeholder engagement, ranging from simply informing people about what you plan to do, to actively seeking consent and placing the final decision in their hands. This range, presented in Figure 9.3, is typically presented as a spectrum or continuum of engagement from the least (left) to most (right) amount of engagement with stakeholders.

A more in-depth understanding of each step will help you understand how stakeholder engagement changes between levels:

- Inform: Provide stakeholders with balanced and objective information to help them understand the project, the problem, and the solution alternatives. There is no opportunity for stakeholder input or decision-making.

- Consult: Gather feedback on the information given. Level of input ranges from minimal interaction (online surveys) to extensive. Can be a one-time or ongoing/iterative opportunities to give feedback to be considered in the decision-making process.

- Involve: Work directly with stakeholders during the process to ensure that their concerns and desired outcomes are fully understood and taken into account at each stage. Final decisions are still made by the consulting organization, but with well-considered input from stakeholders.

- Collaborate: Partner with stakeholders at each stage of the decision-making, including developing alternative solution ideas and choosing the preferred solution together. Goal is to achieve consensus regarding decisions.

- Empower: Place final decision-making power in the hands of stakeholders. Voting ballots and referenda are common examples. This level of stakeholder engagement is rare and usually includes a small number of people who represent important stakeholder groups.

Depending on the type of project, the potential impacts and the types and needs of stakeholders, you may engage in a number of levels and strategies of engagement across this spectrum using a variety of different tools (see Table 9.1):

| Inform | Consult | Involve / Collaborate / Empower |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

There is no single “right” way of consulting with stakeholders. Each situation will be different, so each consultation process will be context-specific and will require a detailed plan. A poorly planned consultation process can backfire, as it can lead to a lack of trust between stakeholders and the researchers. It is critical that the process be carefully mapped out in advance, and that preliminary work is done to determine the needs and goals of the process and the stakeholders involved. In particular, make sure that whatever tools you choose to use are fully accessible to all the stakeholders you plan to consult; an online survey is not much use to a community that lacks robust wifi infrastructure.

Use the steps below to plan stakeholder engagement and consultation:

- Situation Assessment: Who needs to be consulted about what and why? Define stakeholders, determine their level of involvement, interest level, and potential impact, their needs and conditions for effective engagement.

- Goal-setting: What is your strategic purpose for consulting with stakeholders at this phase of the project? Define clear goals and objectives for the role of stakeholders in the decision making process. Determine what questions, concerns, and goals the stakeholders may have and how these can be integrated into the process.

- Planning/Requirements: Based on situation assessment and goals, determine what engagement strategies to use and how to implement them to best achieve these goals. Ensure that strategies consider issues of accessibility and the needs of vulnerable populations. Consider legal or regulatory requirements, policies, or conditions that need to be met. Determine how you will collect, record, track, analyze and distribute the data.

- Process and Event Management: Keep the planned activities moving forward and on-track, and adjust strategies as needed. Keep track of documentation.

- Evaluation: Design an evaluation metric to gauge the success of the engagement strategies; collect, analyze, and act on the data collected throughout the process. Determine how will you report the results of engagement process back to the stakeholders.

Example Stakeholder Engagement Plans

Example 1: Public Participation Guide, EPA

Example 2: Public Participation Plan, NWARPC

The Northwest Arkansas Regional Planning Commission (NWARPC) is an organization dedicated to large-scale regional transit and transportation planning. On their website, they provide a Public Participation Plan (PPP) that details how they intend to solicit stakeholder input. Their stated goal is to “provide opportunities for citizens, employers, and transportation providers to contribute ideas and opinions early and at every stage of the planning process.” Specifically, their plan has three goals:

- “Prioritizes providing complete information, timely notices, access to decisions, and early, ongoing public involvement”;

- “Adapts to regional growth and changing demographics with flexible tools”;

- “Builds on successful past efforts and identifies future strategies without listing every potential engagement opportunity” (NWARPC, 2025).

Designing and Running a Pilot Study[3]

For project 3, you will design and run a pilot study that will help you to write your problem primer and later, your grant proposal. The library at the University of Melbourne describes a pilot study as “a small initial study that is conducted to test the practicality and feasibility of a full research project” (n.d.). Once you’ve conducted the pilot study, you can use it as evidence for your problem primer, and possibly for your grant proposal.

Defining Your Project’s Scope

Often, when you begin a project, the problem is fairly general and open-ended. This allows you to approach the problem in a variety of ways, but also requires you to do some work to decide which approach you will take. Most projects will require careful consideration of scope.

You must define the scope by considering:

- Who is your primary audience? Who else might read this?

- Who are the people who will be affected by this project? Who are the stakeholders?

- What is the specific outcome you want this document or project to achieve? What do you want your readers to do, think, or decide after reading it?

- What is the best format to use to present this project to these readers? What format or specific information have they requested?

- Are there limitations in terms of geography, demographics, or available technology?

- Is there a time frame? A budget?

- Are there legal considerations, regulations, policies, and guidelines that must be taken into account?

Your project will first require background research to clearly define the problem you are tackling – that is why we are taking time to do academic research in addition to the pilot study. Project 3 is intended to help you answer several key questions: How do you know there is a problem? What measurable impacts can you point to? What will you need to prove that this is a significant problem that needs to be addressed? Can you provide data to show the extent of the “unsatisfactory situation” and how it negatively affects people? Is there an expected goal or target that any proposed solution is expected to meet?

In presenting your solution(s), you will have to find research to provide support for the basic premise of your research question (is this idea feasible?) and prove your hypothesis (it will be effective/beneficial). You might do this by showing that similar ideas have been implemented and/or researched in other areas, or that the ideas you are presenting are based on sound evidence. The primary data from your pilot study should help you show how your ideas are feasible in the local community context.

Clearly you can’t solve the problem of climate change in one paper or project and no reasonable reader would expect you to. However, you might be asked to explore effective ways to reduce carbon emissions in a specific industry in a given period of time and/or geographical region. Or you might investigate whether a particular form of alternative energy would be effective in a particular situation. Even then, you would have to consider approaches. Would you recommend changing a policy or law to try to address the causes of the problem? Providing incentives to industry or consumers? Innovating a current technology or process? Creating a new technology or process? Evaluating a currently proposed solution?

Research Methods

For Project 3, you will design a pilot study that uses one of three methods: interviews, surveys, or observations. Which method you choose depends on what type of information will be most helpful to you as you assemble the information that will become evidence for your problem primer and grant proposal. You should brainstorm questions you need to answer, then decide which method is most suitable for that work.

- Interviews: one-on-one or small group question and answer sessions. Interviews will provide detailed information from a small number of people and are useful when you want to get an expert opinion on your topic. For such interviews, you may need to have the participants sign an informed consent form before you begin.

- Observations: watching and taking organized notes about an event or process related to your research. The goal is to be as unobtrusive as possible, so that your presence does not influence or disturb the normal activities you want to observe. If you want to observe activities in a specific place, you must first seek permission and let participants know the nature of the observation. Observations in public places do not normally require approval. However, you may not photograph or video your observations without first getting the participants’ informed voluntary consent and permission.

- Surveys: a form of questioning that is less flexible than interviews, as the questions are set ahead of time and cannot be changed. These involve much larger groups of people than interviews, but result in less detailed responses. Like interviews, surveys require that you get the participants’ informed consent before you begin.

Below, you will find more information about each method so that you can make the best possible decision about the research design for your pilot study. If your research design requires informed consent, talk with your instructor about how to incorporate these documents into your plan.

Interviews

Interviewing requires you to prepare fully and act with purpose. When you plan an interview, you need to know what you’re hoping to get out of the process. You can’t simply go into an interview and let things develop—you’re going to waste your own time and that of your subject(s). Instead, think about what you want to know. Do you want to know about a specific experience? Do you want a broad overview of how a problem happens? Carefully consider your goals and the scope of your questions. One interview shouldn’t do too much or too little.

Time and timeliness also comes into play. Think about how much time you have to complete your pilot study, and what your schedule looks like. Align the type of interview you want with your goals and your timeline – be realistic about what is possible in the time you have. Contact your potential interviewee as soon as possible. Individuals, especially those who work outside academia, may operate on different timelines.

Writing Successful Interview Questions

Preparing good interview questions takes time, practice, and testing. An interview is not simply a conversation – while treating it as such can generate information, you will often find that important questions have not been addressed. It is therefore critical to think about both the content and order of your questions as you design your interview.

Carter McNamara offers the following suggestions for wording interview questions. This passage is quoted in its entirety:

- Wording should be open-ended. Respondents should be able to choose their own terms when answering questions.

- Questions should be as neutral as possible. Avoid wording that might influence answers, e.g. evocative, judgmental wording.

- Questions should be asked one at a time. Avoid asking multiple questions at once. If you have related questions, ask them separately as a follow-up question rather than part of the initial query.

- Questions should be worded clearly. This includes knowing any terms particular to the program or the respondents’ culture.

- Be careful asking “why” questions. This type of question infers a cause-effect relationship that may not truly exist. These questions may also cause respondents to feel defensive, e.g., that they have to justify their response, which may inhibit their responses to this and future questions.

Further, you will want to craft questions with your goals in mind. When you write questions, craft them to get the information you need. Think about who your subject is and why their particular viewpoint or expertise is valuable, and craft questions to draw out that information. That is, you should give your interviewee prompts to direct their answers. You can vary the level of specificity as needed.

- Example Open-Ended Question: What do you think about the proposal to expand the Razorback Greenway to the other side of town?

- Example Specific Question: If the Razorback Greenway opens an extension near Rupple Road, how will that affect the challenges you face with transportation to and from work?

Interview Strategies

Interviews are a very personal form of research – often a one-on-one conversation. Setting the stage for a successful interview requires work on your part to ensure that participants are comfortable and that they understand what is about to happen. The following strategies can help you set the stage for a successful interview:

- Create a sense of comfort. Prepare your interview location beforehand. If you are interviewing in person, try to find a quiet, comfortable space where you won’t be interrupted. Dress to reflect your professional persona – aim to be professional, but comfortable.

- Be clear about the interview structure. Let your subject know what to expect from the interview: what you’ll discuss, the types of questions you will ask, and the length you’re aiming for. This helps them understand what you want and be less anxious about the interview process.

- Consider how you ask questions. Think about your tone as you write and speak your questions. You don’t want to be accusatory or aggressive if your aim is to keep your subject comfortable, nor should you be too personal or sensitive.

Recording Interviews

Regardless of how you choose to do so, you should record information during your interview. Below, we’ll discuss the use of video, audio, and notes for recording, but before we start, it is important to remember that you owe your interview subjects disclosure if you will record them. If you plan to use video or audio, you must tell your subjects beforehand and give them an opportunity to respond. Interviewing is in large part about the relationship you cultivate with your interview subject, so when it comes to taking notes or recording data, being as transparent as possible helps you to do your research ethically.

You have several options for recording notes:

- Video. Using video can preserve body language, facial expressions, and other environmental elements, which may be useful for you as you analyze your interview data. However, video cameras often make people uncomfortable, so you should be aware that this option may affect your interviewee’s behavior.

- Audio. Using audio can record the wording and tone of voice of the interview. You may need to transcribe an audio interview, so allow time for that if this is your recording method. As with video, knowing that there is an audio recorder may make your subjects uncomfortable.

- Notes. Recording notes by hand can be challenging if you don’t practice beforehand – you won’t be able to write down every word your interviewee says, so you will need to think carefully about how to take notes during the process. Be aware that if you make notes as though something is important, your interviewee may pick up on that.

Finally, if you are going to be using anonymous data, you will need to transcribe the interview recordings and anonymize them and then destroy the originals. Voice recordings or video are not anonymous and if you’ve promised that to your subjects, you’ll need to make sure to honor that promise.

Observations

Another research method is observation – one of the simplest of all research methods, depending on the implementation. Use observation to witness people experiencing a problem or going through a process that is relevant to your research questions. Observation is a tool to figure out how folks experience something without intruding into their experience and altering it. You simply sit back and watch the situation, taking notes of things as they happen.

In public, observation can be extremely unobtrusive in that you can sometimes simply blend into the background. You may, for example, want to see how folks navigate the signage in the campus cafeteria. You could simply park yourself near the front of that cafeteria and observe patterns and when folks stop to interpret things. Obviously this would be more useful when you have large groups of folks using these facilities for the first time, such as during orientation week or when a visiting group are present.

In more closed locations, you should have permission to observe. Before observing in such locations, you will need to make sure that you are allowed to be there. You will likely want to keep your recording to written notes, and you may need to get your notes checked with those that you’re working with before you use them or take them out of the location, especially when sensitive information is involved.

Doing Field Observations

To set up for and conduct a field observation, you will need to consider the following:

- Gain appropriate permissions for researching the site. Your site is the location you are observing. Sites could include potential locations for a community garden, a classroom where you’re observing student behaviors or a professor’s teaching strategies, or a local business. Certain sites will require specific permission from an owner or other individual. Depending on your study, you may also need to acquire IRB permission.

- Know what you’re looking for. While people-watching is interesting, your most effective field research will be accomplished if you know roughly what you want to observe. For instance, say you are observing a large lecture from a 100-level class, and you are interested in how students use their laptops, tablets, or phones. In your observation, you would specifically focus on the students, with some attention to how they’re responding to the professor. You would not be as focused on the content of the professor’s lecture or whether the students are doing non-electronic things such as doodling or talking to their classmates.

- Take notes. Select your note-taking option and prepare backups. While in the field, you will be relying primarily on observation. Record as much data as possible and back up that data in multiple formats.

- Be unobtrusive. In field research, you function as an observer rather than a participant. Therefore, do your best to avoid influencing what is happening at the research site.

Recording Observations

Be aware that sensitive information can be relayed during an observation, even if you are doing this work in a public venue. Take care that you’re not going to be recording in a way that will disrupt locations or violate privacy. You may be asked to leave a room during a private observation, and you may need to ignore anything you hear in a more public venue if the content that is being shared would be embarrassing or otherwise troublesome to record and share. Default to written notes with observation, unless there is good reason to do otherwise – this choice allows you to be your own editor as far as what is recorded and what is not. In addition, you should check with those you will be observing to see what types of sensitive information you should ignore or not record.

Interpreting Observational Data

Observation excels at helping you understand how a process, system, or problem actually happens in the physical world. By observing a situation, you can see how folks navigate a situation – when something works, when people become frustrated, and more. In private situations, you get a better sense of how work flows in a given location and the types of interactions that happen in a given space. Each type of information can be valuable for you as a technical writer because it gives you even more information to take into account when you consider the choices you make in your own designs and documents.

Surveys

Surveys allow you to ask a set number and type of questions to a large group of users. Virginia Tech Libraries’ Research Methods Guide: Survey Methods (2025) argues that survey methods allow you to accomplish two goals:

- “Collect information from a small number of people to be representative of a large number of people to be studied”; includes “information about their attributes, behaviors, preferences, attitudes, and opinions” (VT Libraries, 2025);

- “Systematically draw information from a certain population in order to describe demographic information (e.g., age, gender, school year, affiliation), draw patterns from the population studied, [and] explain trends” (VT Libraries, 2025).

You can conduct surveys in a variety of ways, including phone, face-to-face, paper and pencil, and online or web-based (VT Libraries, 2025). Below, you’ll find some tips on writing and designing survey questions that will get you the types of answers you need to complete your pilot study.

Writing Survey Questions

When designing surveys, remember the rhetorical situation:

- What are the goals of your survey?

- Who are you hoping will complete the survey? What will they know? What will they not know?

- How long can you expect them to engage with your survey?

- What is the best method of surveying them (online, say through Google Forms, or in person)?

- How many responses do you hope to obtain?

Use this information to inform the design of your survey and any preliminary materials you include. All surveys should feature clear statements of purpose, as well as specific directions for answering the questions and how to contact the researcher if participants have any questions.

After determining your audience and purpose, you will need to design your questions. Remember, in online surveys you will not be there to provide immediate clarification, so your questions need to be carefully worded to avoid confusion and researcher bias. As a rule, your survey questions should:

- Be as specific as possible. Avoid ambiguity by providing specific dates, events, or descriptions as necessary.

- Ask only one question at a time. Specifically, avoid survey questions that require the participant to answer multiple items at once. This will confuse the reader about what you are looking for and will likely skew your data.

- Be neutral. Present your survey questions without leading, inflammatory, or judgmental language. Avoid using language that is obviously biased.

- Be logically organized. Present questions in a way that makes sense. For example, if you introduce a concept in Question 1, don’t return to it again in Question 12. Follow-up questions and linked questions should be asked in succession rather than separated.

- Allow participants to decline answering. Be wary of questions that require participants to divulge sensitive information, even if they are answering anonymously. This information could include details such as a trauma, eating disorders, or drug use. For research projects that require these questions, consult the university IRB (Internal Review Board).

Designing Survey Questions

After writing the questions, you will also need to consider how your participants can answer them. Depending on your needs, you may opt for quantitative data, which includes yes/no questions, multiple choice, Likert scales, or ranking. Note that what makes this data “quantitative” is that it can be easily converted into numerical data for analysis. Alternatively, you may opt for qualitative data, which includes questions that require a written response from the participant. A description and some of the advantages of these answer styles follow below:

- Yes/No (Quantitative). These simple questions allow for comparison but not much else. They can be useful as a preliminary question to warm up participants or open up a string of follow-up questions.

- Multiple choice (Quantitative). These questions allow for preset answers and are particularly useful for collecting demographic data. For example, a multiple-choice question might look something like this: “How many years have you attended your university?” Depending on the question, you may wish to allow a write-in response.

- Likert scale (Quantitative). The Likert scale is a rating, usually on a 1-5 scale. At one end of the scale, you will have an option such as “Definitely Agree” and on the other side, “Definitely Disagree.” In the middle, if you choose to provide it, is a neutral option. Some answers in this format may use a wider range (1-10, for example), offer a “Not Applicable” option, or remove the neutral option. Be mindful of what these choices might mean. A wider scale could, in theory, mean more nuance, but only if the distinctions between each option are clear.

- Ranking (Quantitative). In a ranking-based answer, you provide a list of options and prompt your participant to place them in a certain order. For example, you may be offering five potential solutions to a specific problem. After explaining the solutions, you ask your reader to identify which of the five is the best, which is second best, and so on. Participants may assign these items a number or rearrange their order on a screen.

- Written responses (Qualitative). Ask for written responses when you want detailed, individualized data. This approach is beneficial in that you may receive particularly detailed responses or ideas that the survey did not address. You might also be able to privilege voices that are often drowned out in large surveys. However, keep in mind that many participants do not like responding to essay-style questions. These responses work best as follow-up questions midway or later in the survey.

Finally, before officially publishing your survey online or asking participants in person, make sure that you conduct preliminary usability testing on your survey. This testing allows you to seek feedback on confusion or ambiguity in question wording, lack of clarity in question order, typographical errors, technical difficulties, and how long the survey took a user to complete. Remember, surveys with unclear questions and sloppy formatting annoy participants and damage your credibility. Conversely, the more professional a survey looks and the easier it is for your reader to complete it, the more likely you will receive useful responses.

Research Progress Memos

As you take time to work through your pilot study, you will be asked to return to a technical genre with which you are already familiar: the memo. You are responsible for one research memo over the time you run your study. Below, you’ll find a brief explanation of how the contents of this memo differ from the memo you composed for Project 1.

Research Memo Contents

A research memo is a subgenre of the memorandum – as we discussed in Chapter 3, memos are documents meant to communicate a clear, specific message about a relevant topic. In this case, you will be communicating with your instructor about your progress on the pilot study for project 3. This makes the research memo (and the design memos you will write during the next project) a very specific type of document: a progress report.

Your research memo you write should answer the following questions:

- How is your pilot study going?

- What academic sources have you identified to use in your project?

- What research do you still need to accomplish?

For a review of memo genre conventions, please see Chapter 3, “Memo Genre Conventions.”

Conclusion

In this chapter, you’ve learned about concepts and tools that will help you to design and run a successful pilot study. The pilot study will inform your writing in the problem primer project; this primary research will provide grounding and connection with a local community who needs help with the problem you are investigating. Next, we’ll explore how to put together your primary and secondary research in the problem primer itself.

References

American Psychological Association. (2025). Human research protections. Retrieved 15 July, 2025, from https://www.apa.org/research-practice/conduct-research/human.

Charrette. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Retrieved 15 July 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charrette.

Driscoll, Cathy and Mark Starik. (2004). The primordial stakeholder: Advancing the conceptual consideration of stakeholder status for the natural environment. Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 55-73. Retrieved 6 July 2025, from https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000013852.62017.0e.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2024). Public participation guide: View and print version. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 6 July 2025, from https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/public-participation-guide-view-and-print-versions.

Hagan, Margaret. (2017). Stakeholder mapping the traffic ticket system. Retrieved 6 July 2025, from https://www.openlawlab.com/2017/08/28/stakeholder-mapping-the-traffic-ticket-system/.

Human Subjects Research Home. (n.d.) University of Arkansas Division of Research and Innovation. Retrieved 15 July 2025, from https://rsic.uark.edu/humansubjects/index.php.

McNamara, Carter. (2009). General guidelines for conducting interviews. Free Management Library. Retrieved 6 July 2025, https://managementhelp.org/businessresearch/interviews.htm.

Northwest Arkansas Regional Planning Commission (NWARPC). (2025). Public participation plan. Retrieved 6 July 2025, from https://www.nwarpc.org/public-participation-plan/.

University of Melbourne Library. (n.d.). Pilot study or feasibility study. University of Melbourne. Retrieved 6 July 2025, from https://unimelb.libguides.com/whichstudytype/Pilot-Feasibility.

Virginia Tech Libraries. (2025). Research methods guide: Survey research. Virginia Tech. Retrieved 6 July 2025, from https://guides.lib.vt.edu/researchmethods/survey.

The World Cafe. (2025). Accessed 15 July, 2025, from https://theworldcafe.com/.

- Based on Suzan Last's "Chapter 5: Conducting Research," in Technical Writing Essentials. ↵

- M. Hagan, “Stakeholder mapping of traffic ticket system,” Open Law Lab [Online] Aug. 28, 2017. Available: http://www.openlawlab.com/2017/08/28/stakeholder-mapping-the-traffic-ticket-system/ . CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.[Accessed Feb 24, 2019]. ↵

- Based on Suzan Last, "Chapter 5: Conducting Research," in Technical Writing Essentials; Adam Pope, "Chapter 7: Research Methods for Technical Writing," in Open Technical Writing; and Suzan Last, Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt and Matt McKinney, "Chapter 11: Research Methods and Methodologies," in Howdy or Hello: Technical and Professional Communication. ↵