Lesson One: Your Personal Health Journey

Dr. Ches Jones, Ph.D.

Lesson One Lecture

Lesson One Slides

Readings and Videos

Theory at a Glance: A Guide For Health Promotion Practice

Part 2: Theories and Applications

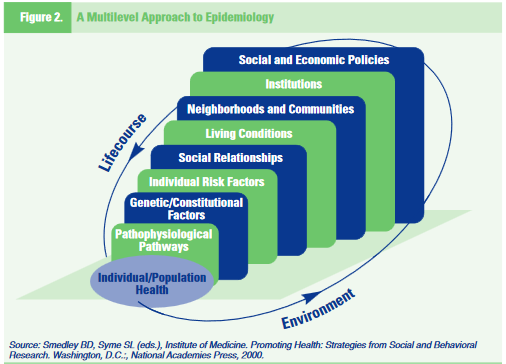

The Ecological Perspective: A Multilevel, Interactive Approach

Contemporary health promotion involves more than simply educating individuals about healthy practices. It includes efforts to change organizational behavior, as well as the physical and social environment of communities. It is also about developing and advocating for policies that support health, such as economic incentives. Health promotion programs that seek to address health problems across this spectrum employ a range of strategies, and operate on multiple levels.

The ecological perspective emphasizes the interaction between, and interdependence of, factors within and across all levels of a health problem. It highlights people’s interactions with their physical and socio-cultural environments. Two key concepts of the ecological perspective help to identify intervention points for promoting health: first, behavior both affects, and is affected by, multiple levels of influence; second, individual behavior both shapes, and is shaped by, the social environment (reciprocal causation).

To explain the first key concept of the ecological perspective, multiple levels of influence, McLeroy and colleagues (1988)[1] identified five levels of influence for health-related behaviors and conditions. Defined in Table 1., these levels include: (1) intrapersonal or individual factors; (2) interpersonal factors; (3) institutional or organizational factors; (4) community factors; and (5) public policy factors.

|

Table 1. |

An Ecological Perspective: Levels of Influence |

|

|

Concept |

Definition |

|

|

Intrapersonal Level |

Individual characteristics that influence behavior, such as knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and personality traits |

|

|

Interpersonal Level |

Interpersonal processes and primary groups, including family, friends, and peers that provide social identity, support, and role definition |

|

|

Community Level |

||

|

Institutional Factors |

Rules, regulations, policies, and informal structures, which may constrain or promote recommended behaviors |

|

|

Community Factors |

Social networks and norms, or standards, which exist as formal or informal among individuals, groups, and organizations |

|

|

Public Policy |

Local, state, and federal policies and laws that regulate or support healthy actions and practices for disease prevention, early detection, control and management |

|

In practice, addressing the community level requires taking into consideration institutional and public policy factors, as well as social networks and norms. Figure 2. illustrates how different levels of influence combine to affect population health.

Each level of influence can affect health behavior. For example, suppose a woman delays getting a recommended mammogram (screening for breast cancer). At the individual level, her inaction may be due to fears of finding out she has cancer.

At the interpersonal level, her doctor may neglect to tell her that she should get the test, or she may have friends who say they do not believe it is important to get a mammogram. At the organizational level, it may be hard to schedule an appointment, because there is only a part-time radiologist at the clinic. At the policy level, she may lack insurance coverage, and thus be unable to afford the fee. Thus, the outcome, the woman’s failure to get a mammogram, may result from multiple factors.

The second key concept of an ecological perspective, reciprocal causation, suggests that people both influence, and are influenced by, those around them. For example, a man with high cholesterol may find it hard to follow the diet his doctor has prescribed because his company cafeteria doesn’t offer healthy food choices. To comply with his doctor’s instructions, he can try to change the environment by asking the cafeteria manager to add healthy items to the menu, or he can dine elsewhere. If he and enough of his fellow employees decide to find someplace else to eat, the cafeteria may change its menu to maintain lunch business. Thus, the cafeteria environment may compel this man to change his dining habits, but his new habits may ultimately bring about change in the cafeteria as well.

An ecological perspective shows the advantages of multilevel interventions that combine behavioral and environmental components. For instance, effective tobacco control programs often use multiple strategies to discourage smoking[2]. Employee smoking cessation clinics have a stronger impact if the workplace has a no-smoking policy and the city has a clean indoor air ordinance. Adolescents are less likely to begin smoking if their peers disapprove of the habit and laws prohibiting tobacco sales to minors are strictly enforced. Health promotion programs are more effective when planners consider multiple levels of influence on health problems.

Theoretical Explanations of Three Levels of Influence

The next three sections examine theories and their applications at the individual (intrapersonal), interpersonal, and community levels of the ecological perspective. At the individual and interpersonal levels, contemporary theories of health behavior can be broadly categorized as “Cognitive-Behavioral.” Three key concepts cut across these theories:

- Behavior is mediated by cognitions; that is, what people know and think affects how they act.

- Knowledge is necessary for, but not sufficient to produce, most behavior changes.

- Perceptions, motivations, skills, and the social environment are key influences on behavior.

Community-level models offer frameworks for implementing multi-dimensional approaches to promote healthy behaviors. They supplement educational approaches with efforts to change the social and physical environment to support positive behavior change.

Individual or Intrapersonal Level

The individual level is the most basic one in health promotion practice, so planners must be able to explain and influence the behavior of individuals. Many health practitioners spend most of their work time in one-on-one activities such as counseling or patient education, and individuals are often the primary target audience for health education materials. Because individual behavior is the fundamental unit of group behavior, individual-level behavior change theories often comprise broader-level models of group, organizational, community, and national behavior. Individuals participate in groups, manage organizations, elect and appoint leaders, and legislate policy. Thus, achieving policy and institutional change requires influencing individuals.

In addition to exploring behavior, individual- level theories focus on intrapersonal factors (those existing or occurring within the individual self or mind). Intrapersonal factors include knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, motivation, self-concept, developmental history, past experience, and skills. Individual-level theories are presented below.

- The Health Belief Model (HBM) addresses the individual’s perceptions of the threat posed by a health problem (susceptibility, severity), the benefits of avoiding the threat, and factors influencing the decision to act (barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy).

- The Stages of Change (Transtheoretical) Model describes individuals’ motivation and readiness to change a behavior.

- The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) examines the relations between an individual’s beliefs, attitudes, intentions, behavior, and perceived control over that behavior.

- The Precaution Adoption Process Model (PAPM) names seven stages in an individual’s journey from awareness to action. It begins with lack of awareness and advances through subsequent stages of becoming aware, deciding whether or not to act, acting, and maintaining the behavior.

Health Belief Model (HBM)

The Health Belief Model (HBM) was one of the first theories of health behavior, and remains one of the most widely recognized in the field. It was developed in the 1950s by a group of U.S. Public Health Service social psychologists who wanted to explain why so few people were participating in programs to prevent and detect disease. For example, the Public Health Service was sending mobile X-ray units out to neighborhoods to offer free chest X-rays (screening for tuberculosis). Despite the fact that this service was offered without charge in a variety of convenient locations, the program was of limited success. The question was, “Why?”

To find an answer, social psychologists examined what was encouraging or discouraging people from participating in the programs. They theorized that people’s beliefs about whether or not they were susceptible to disease, and their perceptions of the benefits of trying to avoid it, influenced their readiness to act.

In ensuing years, researchers expanded upon this theory, eventually concluding that six main constructs influence people’s decisions about whether to take action to prevent, screen for, and control illness. They argued that people are ready to act if they:

- Believe they are susceptible to the condition (perceived susceptibility)

- Believe the condition has serious consequences (perceived severity)

- Believe taking action would reduce their susceptibility to the condition or its severity (perceived benefits)

- Believe costs of taking action (perceived barriers) are outweighed by the benefits

- Are exposed to factors that prompt action (e.g., a television ad or a reminder from one’s physician to get a mammogram) (cue to action)

- Are confident in their ability to successfully perform an action (self-efficacy)

Since health motivation is its central focus, the HBM is a good fit for addressing problem behaviors that evoke health concerns (e.g., high-risk sexual behavior and the possibility of contracting HIV). Together, the six constructs of the HBM provide a useful framework for designing both short-term and long-term behavior change strategies. (See Table 2.) When applying the HBM to planning health programs, practitioners should ground their efforts in an understanding of how susceptible the target population feels to the health problem, whether they believe it is serious, and whether they believe action can reduce the threat at an acceptable cost. Attempting to effect changes in these factors is rarely as simple as it may appear

|

Table 2. |

Health Belief Model |

|

|

Concept |

Definition |

Potential Change Strategies |

|

Perceived susceptibility |

Beliefs about the chances of getting a condition |

|

|

Perceived severity

|

Beliefs about the seriousness of a condition and its consequences and its consequences |

|

|

Perceived benefits |

Beliefs about the effectiveness of taking action to reduce risk or seriousness |

|

|

Perceived barriers

|

Beliefs about the material and psychological costs of taking action |

|

|

Cues to action |

Factors that activate ”readiness to change” |

|

|

Self-efficacy |

Confidence in one’s ability to take action |

|

High blood pressure screening campaigns often identify people who are at high risk for heart disease and stroke, but who say they have not experienced any symptoms. Because they don’t feel sick, they may not follow instructions to take prescribed medicine or lose weight. The HBM can be useful for developing strategies to deal with noncompliance in such situations.

According to the HBM, asymptomatic people may not follow a prescribed treatment regimen unless they accept that, though they have no symptoms, they do in fact have hypertension (perceived susceptibility). They must understand that hypertension can lead to heart attacks and strokes (perceived severity). Taking prescribed medication or following a recommended weight loss program will reduce the risks (perceived benefits) without negative side effects or excessive difficulty (perceived barriers). Print materials, reminder letters, or pill calendars might encourage people to consistently follow their doctors’ recommendations (cues to action). For those who have, in the past, had a hard time losing weight or maintaining weight loss, a behavioral contract might help establish achievable, short-term goals to build confidence (self-efficacy).

Stages of Change (Transtheoretical) Model of change.

Developed by Prochaska and DiClemente[3], the Stages of Change Model evolved out of studies comparing the experiences of smoker who quit on their own with those of smokers receiving professional treatment. The model’s basic premise is that behavior change is a process, not an event. As a person attempts to change a behavior, he or she moves through five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance (see Table 3.). Definitions of the stages vary slightly, depending on the behavior at issue. People at different points along this continuum have different informational needs, and benefit from interventions designed for their stage.

Whether individuals use self-management methods or take part in professional programs, they go through the same stages of change nonetheless, the manner in which they pass through these stages may vary, depending on the type of behavior change. For example, a person who is trying to give up smoking may experience the stages differently than someone who is seeking to improve their dietary habits by eating more fruits and vegetables.

The Stages of Change Model has been applied to a variety of individual behaviors, as well as to organizational change. The Model is circular, not linear. In other words, people do not systematically progress from one stage to the next, ultimately “graduating” from the behavior change process. Instead, they may enter the change process at any stage, relapse to an earlier stage, and begin the process once more. They may cycle through this process repeatedly, and the process can truncate at any point.

|

Table 3. |

Stages of Change Model |

|

|

Stage |

Definition |

Potential Change Strategies |

|

Precontemplation |

Has no intention of taking action within the next six months |

Increase awareness of need for change; personalize information about risks and benefits |

|

Contemplation |

Intends to take action in the next six months |

Motivate; encourage making specific plans |

|

Preparation |

Intends to take action within the next thirty days and has taken some behavioral steps in this direction |

Assist with developing and implementing concrete action plans; help set gradual goals |

|

Action |

Has changed behavior for less than six months |

Assist with feedback, problem solving, social support, and reinforcement |

|

Maintenance |

Has changed behavior for more than six months |

Assist with coping, reminders, finding alternatives, avoiding slips/relapses (as applicable) |

Suppose a large company hires a health educator to plan a smoking cessation program for its employees who smoke (200 people). The health educator decides to offer group smoking cessation clinics to employees at various times and locations. Several months pass, however, and only 50 of the smokers sign up for the clinics. At this point, the health educator faces a dilemma: how can the 150 smokers who are not participating in the clinics be reached?The Stages of Change Model offers perspective on ways to approach this problem. First, the model can be employed to help understand and explain why they are not attending the clinics. Second, it can be used to develop a comprehensive smoking program to help more current and former smokers change their smoking behavior, and maintain that change. By asking a few simple questions, the health educator can assess what stages of contemplation potential program participants are in. For example:

- Are you interested in trying to quit smoking? (Pre-contemplation)

- Are you thinking about quitting smoking soon? (Contemplation)

- Are you ready to plan how you will quit smoking? (Preparation)

- Are you in the process of trying to quit smoking? (Action)

- Are you trying to stay smoke-free? (Maintenance)

The employees’ responses will help to pinpoint where the participants are on the continuum of change, and to tailor messages, strategies, and programs appropriate to their needs. For example, individuals who enjoy smoking are not interested in trying to quit, and therefore will not attend a smoking cessation clinic; for them, a more appropriate intervention might include educational interventions designed to move them out of the “precontemplation” stage and into “contemplation” (e.g., using carbon monoxide testing to demonstrate the effect of smoking on health). On the other hand, individuals who are ready to plan how to quit smoking (the “preparation” stage) can be encouraged to do so, and moved to the next stage, “action.”

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

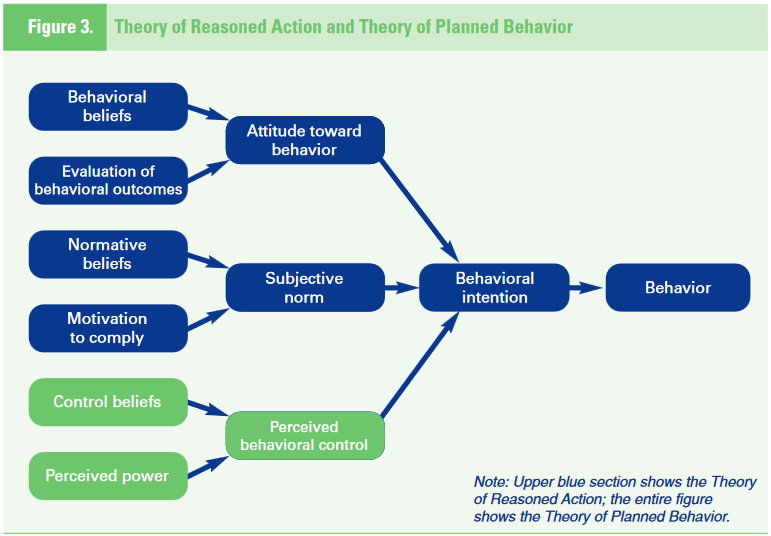

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the associated Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) explore the relationship between behavior and beliefs, attitudes, and intentions. Both the TPB and the TRA assume behavioral intention is the most important determinant of behavior.

According to these models, behavioral intention is influenced by a person’s attitude toward performing a behavior, and by beliefs about whether individuals who are important to the person approve or disapprove of the behavior (subjective norm). The TPB and TRA assume all other factors (e.g., culture, the environment) operate through the models’ constructs, and do not independently explain the likelihood that a person will behave a certain way.

The TPB differs from the TRA in that it includes one additional construct, perceived behavioral control; this construct has to do with people’s beliefs that they can control a particular behavior. Azjen and Driver[4] added this construct to account for situations in which people’s behavior, or behavioral intention, is influenced by factors beyond their control. They argue that people might try harder to perform a behavior if they feel they have a high degree of control over it. (See Table 4.) It has application beyond these limited situations, however. People’s perceptions about controllability may have an important influence on behavior.

|

Table 4. |

Theory of Planned Behavior |

|

|

Concept |

Definition |

Measurement Approach |

|

Behavioral intention |

Perceived likelihood of performing behavior |

Are you likely or unlikely to (perform the behavior)? |

|

Attitude |

Personal evaluation of the behavior |

Do you see (the behavior) as good, neutral, or bad? |

|

Subjective norm |

Beliefs about whether key people approve or disapprove of the behavior; motivation to behave in a way that gains their approval |

Do you agree or disagree that most people approve of/disapprove of (the behavior)? |

|

Perceived behavioral control |

Belief that one has, and can exercise, control over performing the behavior |

Do you believe (performing the behavior) is up to you, or not up to you? |

Surveillance data show that young, acculturated Hispanic women are more likely to get Pap tests than those who are older and less acculturated.[5] A health department decides to implement a cervical cancer screening program targeting older Hispanic women. In planning the campaign, practitioners want to conduct a survey to learn what beliefs, attitudes, and intentions in this population are associated with seeking a Pap test. They design the survey to gauge: when the women received their last Pap test (behavior); how likely they are to seek a Pap test (intention); attitudes about getting a Pap test (attitude); whether or not “most people who are important to me” would want them to get a Pap test (subjective norm); and whether or not getting a Pap test is something that is “under my control” (perceived behavioral control). The department will compare survey results with data about who has or has not received a Pap test to identify beliefs, attitudes, and intentions that predict seeking one.

Figure 3. shows the TPB’s explanation for how behavioral intention determines behavior, and how attitude toward behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control influence behavioral intention. According to the model, attitudes toward behavior are shaped by beliefs about what is entailed in performing the behavior and outcomes of the behavior. Beliefs about social standards and motivation to comply with those norms affect subjective norms. The presence or lack of things that will make it easier or harder to perform the behavior affect perceived behavioral control. Thus, a causal chain of beliefs, attitudes, and intentions drives behavior.

Precaution Adoption Process Model

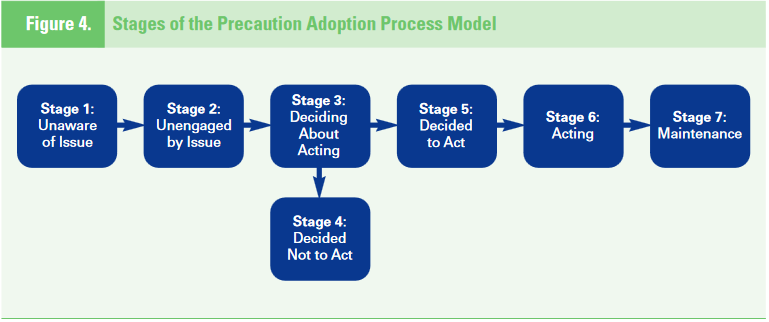

The Precaution Adoption Process Model (PAPM) specifies seven distinct stages in the journey from lack of awareness to adoption and/or maintenance of a behavior. It is a relatively new model that has been applied to an increasing number of health behaviors, including: osteoporosis prevention, colorectal cancer screening, mammography, hepatitis B vaccination, and home testing for radon gas.

In the first stage of the PAPM, an individual may be completely unaware of a hazard (e.g., radon exposure, the link between unprotected sex and HIV). The person may subsequently become aware of the issue but remain unengaged by it (Stage 2). Next, the person faces a decision about acting (Stage 3); may decide not to act (Stage 4), or may decide to act (Stage 5). The stages of action (Stage 6) and maintenance (Stage 7) follow. (See Figure 4.) According to the PAPM, people pass through each stage of precaution adoption without skipping any of them. It is possible for people to move backwards from some later stages to earlier ones, but once they have completed the first two stages of the model they do not return to them. For example, a person does not move from unawareness to awareness and then back to unawareness.

The PAPM bears similarities to the Stages of Change model, but differs in important ways. Stages of Change offers insights for addressing hard-to-change behaviors such as smoking or overeating; it is less helpful when dealing with hazards that have recently been recognized or precautions that are newly available. The PAPM recognizes that people who are unaware of an issue, or are unengaged by it, face different barriers from those who have decided not to act. The PAPM prompts practitioners to develop intervention strategies that take into account the stages that precede active decision-making.

Interpersonal Level

At the interpersonal level, theories of health behavior assume individuals exist within, and are influenced by, a social environment. The opinions, thoughts, behavior, advice, and support of the people surrounding an individual influence his or her feelings and behavior, and the individual has a reciprocal effect on those people. The social environment includes family members, coworkers, friends, health professionals, and others. Because it affects behavior, the social environment also impacts health. Many theories focus at the interpersonal level, but this monograph highlights Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). SCT is one of the most frequently used and robust health behavior theories. It explores the reciprocal interactions of people and their environments, and the psychosocial determinants of health behavior.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) describes a dynamic, ongoing process in which personal factors, environmental factors, and human behavior exert influence upon each other.

According to SCT, three main factors affect the likelihood that a person will change a health behavior: (1) self-efficacy, (2) goals, and (3) outcome expectancies. If individuals have a sense of personal agency or self- efficacy, they can change behaviors even when faced with obstacles. If they do not feel that they can exercise control over their health behavior, they are not motivated to act, or to persist through challenges.[6] As a person adopts new behaviors, this causes changes in both the environment and in the person. Behavior is not simply a product of the environment and the person, and environment is not simply a product of the person and behavior.

SCT evolved from research on Social Learning Theory (SLT), which asserts that people learn not only from their own experiences, but by observing the actions of others and the benefits of those actions. Bandura updated SLT, adding the construct of self-efficacy and renaming it SCT. (Though SCT is the dominant version in current practice, it is still sometimes called SLT.) SCT integrates concepts and processes from cognitive, behaviorist, and emotional models of behavior change, so it includes many constructs. (See Table 5.) It has been used successfully as the underlying theory for behavior change in areas ranging from dietary change[7] to pain control.[8]

|

Table 5. |

Social Cognitive Theory |

|

|

Concept |

Definition |

Potential Change Strategies |

|

Reciprocal determinism |

The dynamic interaction of the person, behavior, and the environment in which the behavior is performed |

Consider multiple ways to promote behavior change, including making adjustments to the environment or influencing personal attitudes |

|

Behavioral capability |

Knowledge and skill to perform a given behavior |

Promote mastery learning through skills training |

|

Expectations |

Anticipated outcomes of a behavior |

Model positive outcomes of healthful behavior |

|

Self-efficacy |

Confidence in one’s ability to take action and overcome barriers |

Approach behavior change in small steps to ensure success; be specific about the desired change |

|

Observational learning (modeling) |

Behavioral acquisition that occurs by watching the actions and outcomes of others’ behavior |

Offer credible role models who perform the targeted behavior |

|

Reinforcements |

Responses to a person’s behavior that increase or decrease the likelihood of reoccurrence |

Promote self-initiated rewards and incentives |

Reciprocal determinism describes interactions between behavior, personal factors, and environment, where each influences the others. Behavioral capability states that, to perform a behavior, a person must know what to do and how to do it. Expectations are the results an individual anticipates from taking action. Bandura considers self-efficacy the most important personal factor in behavior change, and it is a nearly ubiquitous construct in health behavior theories. Strategies for increasing self-efficacy include: setting incremental goals (e.g., exercising for 10 minutes each day); behavioral contracting (a formal contract, with specified goals and rewards); and monitoring and reinforcement (feedback from self-monitoring or record keeping).

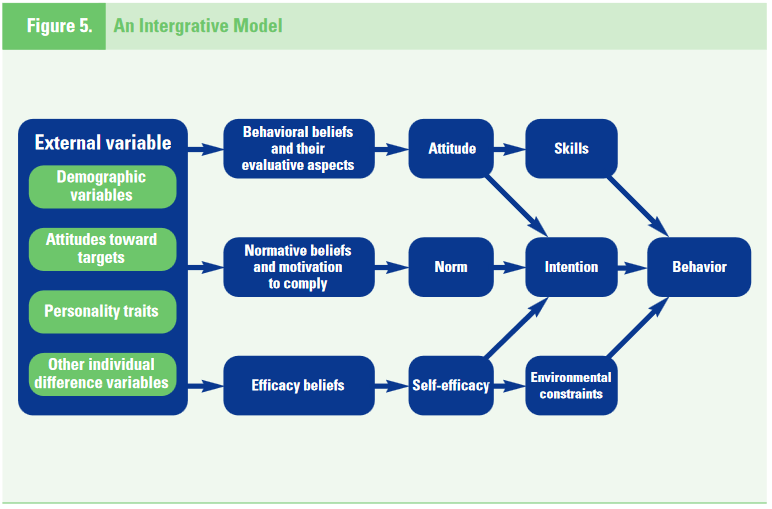

Observational learning, or modeling, refers to the process whereby people learn though the experiences of credible others, rather than through their own experience. Reinforcements are responses to behavior that affect whether or not one will repeat it. Positive reinforcements (rewards) increase a person’s likelihood of repeating the behavior. Negative reinforcements may make repeated behavior more likely by motivating the person to eliminate a negative stimulus (e.g., when drivers put the key in the car’s ignition, the beeping alarm reminds them to fasten their seatbelt). Reinforcements can be internal or external. Internal rewards are things people do to reward themselves. External rewards (e.g., token incentives) encourage continued participation in multiple-session programs, but generally are not effective for sustaining long-term change because they do not bolster a person’s own desire or commitment to change. Figure 5. illustrates how self-efficacy, environmental, and individual factors impact behavior.

A university in a rural area develops a church-based intervention to help congregation members change their habits to meet cancer risk reduction guidelines (behavior). Many members of the church have low incomes, are overweight, rarely exercise, eat foods that are high in sugar and fat, and are uninsured (personal factors). Because of their rural location, they often must drive long distances to attend church, visit health clinics, or buy groceries (environment).

The program offers classes that teach healthy cooking and exercise skills (behavioral capability). Participants learn how eating a healthy diet and exercising will benefit them (expectations). Health advisors create contracts with participants, setting incremental goals (self-efficacy). Respected congregation members serve as role models (observational learning). Participants receive T-shirts, recipe books, and other incentives, and are taught to reward themselves by making time to relax (reinforcement). As church members learn about healthy lifestyles, they bring healthier foods to church, reinforcing their healthy habits (reciprocal determinism).

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly 15:351–377, 1988 ↵

- Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. Atlanta Ga.: August 1999 ↵

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51(3): 390–395, 1983 ↵

- Azjen I, Driver BL. Prediction of leisure participation from behavioral, normative, and control beliefs: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Leisure Science 13:185–204, 1991. ↵

- Mandelblatt JS, Gold K, O’Malley AS, et al. Breast and cervix cancer screening among multiethnic women: Role of age, health, and source of care. Preventive Medicine 28:418–425, 1999. ↵

- Institute of Medicine, op. cit. ↵

- Baranowski T, et al. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among 4th and 5th grade students: results from focus groups using reciprocal determinism. Journal of Nutrition Education 25:114–327, 1993. ↵

- Lorig K, Sobel D, Stewart A, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization. Medical Care 37(1):5–14, 1999. ↵