9 When Words Were Written

Do you remember learning to write? What did it look like? Did you learn block letters or cursive or something else? Can you imagine a written language without letters, a written form with pictures or even numbers that you can read? Reflect upon these questions as you prepare to read this chapter on writing.

As Elizabeth Hill Boone has suggested, writing is “the communication of relatively specific ideas in a conventional manner by means of permanent, visible marks.”[1] In colonial European standards, that largely meant writing words, sentences, paragraphs, letters and so on with a quill pen on paper or with a printing press. However, such verbal and visual word-for-word communication was not prevalent among Native peoples at that time the French established themselves on the North American continent. Indeed, the Recollet priest, Father Hennepin, a most untrustworthy source on the Mississippi, criticized the Indigenous and their lack of written language as he saw it. In Hennepin’s opinion, without written language, the Native peoples had no history.[2]

It is true that Native languages did not have a written, character-based alphabet, nor written words or phrases, paragraphs, or full documents used by Europeans. Nonetheless, language was most certainly written across the North American continent through multiple forms we have previously explored—petroglyphs and pictographs, markings on quirts, winter counts, painted robes and skins, peeled trees, pottery—but also through hieroglyphs, an iconic written form that was the closest to what Europeans considered “written language.” Each of these visual forms of language represented a writing style that expressed history, thoughts, prayers, interaction with others, communication. Indeed, “the situation in the Americas was never a case of writing societies [Europeans] confronting nonwriting societies. Rather, it was one of various kinds of writing and degrees of literacy interacting in complex, historically specific ways.”[3] With time, as French missionaries began to interact with Native peoples and to record the phonetics of their languages, only then did any permanent character or alphabet-based written form of Indigenous language begin to emerge along segments of the Mississippi to satisfy French needs. Eventually, some Native groups developed their own, character-based language and began to more fully communicate in their own, satisfying way.

Hieroglyphs

Before the French arrived in the New World, the ability to code and decode written text was far more prevalent among the better educated than the lower classes of society across France. Thus, church leaders often relied on imagery and gestures to help teach their own people, in particular those moving from Protestant traditions to Catholicism. As French colonists pushed across the North American continent, some transplanted these styles of teaching to the Native peoples they encountered in the New World. Not surprisingly, they soon discovered that some Native groups already used various forms of visual written communication, symbolic communicative devices which were either ephemeral or permanent.

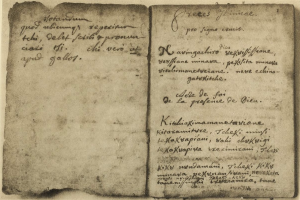

The Abenakis of modern-day Maine and the Mi’kmaqs of Nova Scotia used hieroglyphs for communicating in written form. Mi’kmaq hieroglyphs in particular were already visible as petroglyphs that predate the earliest missionaries in the region. European missionaries became interested in these hieroglyphs when they witnessed the Mi’kmaqs “spontaneously keeping notes for themselves as missionaries talk,” suggesting that hieroglyphs were readily used for communicative purposes in portable form as well.[4] Indeed, “recording facts and important deeds on birch bark and preserving them in carefully crafted cases (often beaded with wampum or porcupine quills) was nothing new and predated the encounter with European alphabetic literacy.”[5] Consequently, missionaries intrigued by such symbolic writing developed the idea of using these symbols in their Christian teachings.

The Recollet Father Chrestien LeClercq, “after witnessing that children ‘were making marks with charcoal upon birch-bark’ during his lessons ‘and were counting these with the finger very accurately at each word of prayers which they pronounced,'” adapted Mi’kmaq hieroglyphs to Christian stories to help the Mi’kmaqs learn prayers and other elements of Christianity.[6] As Father LeClercq worked to teach the Mi’kmaqs, “the hieroglyphic script played a mediating role between, on the one hand, a culture with alphabetic literacy and the linguistic habits of a ‘religion of the book’ [French Catholicism] and, on the other hand, a culture with an economy of language that combined oral systems of knowledge creation and transmission with visual representations of ideas.”[7] But as we have previously discussed, sharing Christian teachings, even with Mi’kmaq or other Native languages was never easy. As one Mi’kmaq exclaimed to the Spiritain priest, Father Pierre Maillard, “everything you have given us to learn is truly Mi’kmaq in terms of its words and their arrangement, but we do not catch the sense of what you want to say.”[8]

While hieroglyphs may have helped the missionaries attempt to teach Christianity to the Mi’kmaqs, these same men developed their own versions of an alphabet-based Native language presumably to maintain word for word transcriptions and assist their own learning of the material. Father Pierre Maillard had a written version of Mi’kmaq using Roman characters but did not share this version with the Native nation. Instead, “he openly states his desire to remain in control of the flow of information between French missionaries and the Mi’kmaq. He says that if the Mi’kmaq ‘should be in a state to use, as we do, our alphabet, be it to read or to write, they inevitably would abuse this knowledge through this spirit of curiosity…which hurriedly drives them to know bad things rather than good….’” Indeed, Maillard believed that alphabetic literacy among the Mi’kmaq would create a strategic threat for the French: “‘[T]hey would be capable of causing great harm amongst the people, as much with respect to religion and behavior as with respect to politics and government.’…[t]hat to…substitute the alphabet for the characters which the Indians use to read and write, this would work very badly, for them as for us.’”[9] In short, Maillard preferred that the Mi’kmaq consider books as faith-based objects and nothing more. He preferred that they remain isolated by their hieroglyphic texts and not expand into alphabet-based communication that could move them beyond the boundaries of what they had access to during his oversight. If they could gain access to alphabetic writing, this form of communication “would dangerously gratify the ‘spirit of curiosity’ that is part of Mi’kmaq character.”[10]

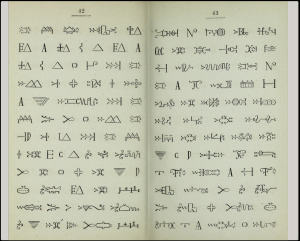

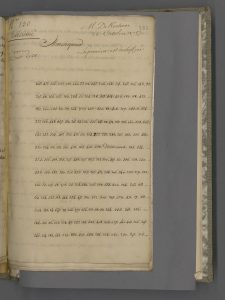

Examples of Mi’Kmaq Writing

The use of the Mi’kmaq Christian writing system continued for decades with a few texts that survive to this day including Pierre Maillard’s eighteenth century prayerbook and Father Christian Kauder’s nineteenth century manuscript. This Viennese Catholic missionary arranged to have a manuscript printed in Vienna.[11] Despite his efforts to publish the text, a ship carrying many of the volumes of this book was lost as it headed to Nova Scotia. Thankfully, copies of this and other texts remain today.

As the decades and centuries passed, the Mi’kmaqs continued to use the hieroglyphic writing system but eventually developed full use of alphabet-based writing as well. In the 20th century, Father Pacifique was certain that the hieroglyphs would fall by the wayside. But what he found was “the Mi’maq, almost completely deprived of the services of priests during long years, have conserved their faith with a perseverance and a unanimity that is almost prodigious. They have copied and recopied without giving up the notebooks of their apostle [Maillard] And, in spite of inevitable gaps, in such a case where there is no person in authority, the book they call their Bible has sustained them in the knowledge and practice of their religion. For 128 years they have conveyed one to another these sacred hieroglyphs.”[12] Indeed, in a relatively recent Good Friday service at Eskasoni, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, those present made use of komqwejwi’kasikl, or hieroglyphs, marking a 300 year old tradition: “An elderly man praying from his tattered hieroglyphic missal…; the young nujialasutmat [prayer leader] reciting the Passion from a version recently published in the script; hieroglyphic characters…painted on church walls, embroidered on the priest’s vestments, and stitched into the altar cloth….In Mi’kmaq homes, silk-screened hieroglyphic prayers hang from kitchen walls, and drawings of hieroglyphic figures decorate classrooms in the reserve grade school.”[13]

Phonetically Written Alphabetic-Based Language

As Europeans encountered Native nations who did not use hieroglyphs for communication, they had to rely on phonetic and alphabet-based writing to record Native terms. The earliest known North American list of Indigenous words written phonetically by the French stems from Jacques Cartier’s 1534 voyage to Canada. This list included words focused on body parts such as the head, legs, eyes, and hair; words for man and woman; even words “linked to mundane objects and materials, both European and Indian in origin, that would have been readily available during the encounter and could be pointed at to exchange vocabularies.” This included such items as hatchets, gold, red cloth, swords, knives and arrows. And of course food items including cod, bread and meat, or even words associated with earth and sky: sun, day, night, wind, rain. Though the word God was included, no Native translation of the word was provided.[14]

Along the 17th and 18th century Mississippi River, missionaries also relied on lists of phonetic and alphabet-based words that they created as they collaborated with Native peoples to write prayer books or hymns. Thus, as with maps discussed in Chapter 5, writing in an alphabet-based Native language was a collaborative event. Father Mark Bergier and the Cahokias certainly collaborated at times. The Seminarian father had a hymn translated by some Cahokia woman and then sought their pronunciation assistance so to more properly chant the song or sing it with others.[15] Unfortunately, the hymn is not known to have survived. Father Bergier even began to create his own dictionary, something he hoped would alleviate his total dependence upon the Native peoples. But French priests had to communicate, and to do so, they had to rely on the goodness and generosity of the Native people among whom they worked; they had to reciprocate in this give and take process, for without an Indigenous writing system, missionaries had to record in written, phonetic form what they learned and understood from the Native peoples. Only then could they develop a written language in the Native tongue for their Christian purposes.

The earliest alphabet-based Native language on the Mississippi River was phonetically transcribed and or used by Allouez and Marquette, the first known Frenchmen to study the Miami-Illinois language while interacting with Illinois traders who visited them at the Holy Spirit Mission in Chequamegon Bay. From the knowledge gained in this mission, Marquette developed his Illinois prayer book that contains translations of the “Ave,” the Lord’s Prayer, and a brief catechism lesson in written alphabet form.[16] But as more Jesuits moved into the Illinois region, these priests used their linguistic skills to write down the language and to use it to write additional liturgical texts. Jesuits Gabriel Marest, Jean-François Pinet, Jacques Gravier, and Jean-Baptiste Antoine Robert Le Boullenger in particular, collectively developed dictionaries, prayer materials and the like, all written in phonetically and alphabetically-based Illinois language, to help preserve the language and help them teach Christianity to the Kaskaskias and Miamis among others.

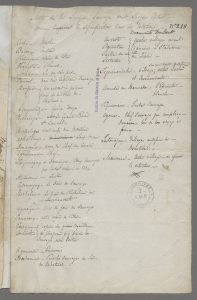

by Jacques Gravier; https://archive.org/details/Gravierp2/page/n41/mode/2up

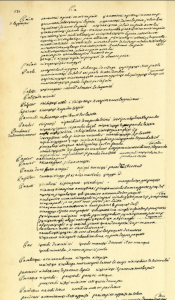

Jacques Gravier spent 15 years among the Illinois and wrote a 590-page Kaskaskia-to-French dictionary in the 1690s. Arranging his dictionary by alphabetized Native words helped Gravier to understand what was being said to him. Otherwise such a strategy was not helpful for someone wanting to know how to say something like “tobacco” in the Native language.[17] Housed today at the Watkinson Library at Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, this dictionary includes useful expressions that reflect the form of his lessons: “I repeat after him word for word;” apologetic phrases such as “I speak a foreign language;” and other expressions to recognize the language barrier: “I have a bad accent,” “I cannot find the word,” “I find nothing to say,” and “I try to speak not knowing the language well.”[18] Evidence further suggests that Gravier was also working on an Illinois grammar text prior to his death.[19]

Jean-François Pinet first served among the Miami-Illinois in the Wea village at modern day Chicago. He later served among the Illinois-speaking Tamarois and then their linguistic kinsmen, the Kaskaskias at what would later become St. Louis. Between 1696 and 1702, he wrote his 672-page French-to-Illinois dictionary. Though the Pinet dictionary is only attributed to this particular missionary, closer analysis has concluded that others contributed to it including Fathers Gabriel Marest and Jean Mermet as well as the coureur de bois turned Jesuit priest, Jacques Largillier. Also known as le castor or “the beaver”, Largillier lived among the various Illinois communities and served the Jesuits in the region both as fellow Jesuit and as scribe until his death in 1714. Indeed, Largillier was with Marquette and Jolliet during their early encounters with the Illinois in 1673 and was with the ailing Marquette when he died the same year. He is also thought to be the transcriber of Gravier’s dictionary.

Unlike the more pristine Gravier (Largillier) dictionary, Pinet’s dictionary appears to be in the Wea dialect of Miami. Notes of language differences appear in the dictionary since Pinet took it with him as he moved on to the Tamarois village and later the Kaskaskia village just before its movement farther south, below the modern St. Louis region. After Pinet’s death, the dictionary seems to have remained in the Kaskaskia mission where other missionaries wrote in their own additions and corrections. Ultimately, the Pinet dictionary likely supported the creation of the dictionary which Le Boullenger began sometime after 1719.[20] Jean-Baptiste Antoine Robert Le Boullenger, who served in the region for some 37 years (1719-1740), wrote his 189-page French-to-Illinois dictionary, a catechism, and grammar, in the 1720s. Today, this dictionary is held at Brown University in the John Carter Brown library.[21]

Finally, during his work among the Kaskaskias, Gabriel Marest created an Illinois to French dictionary “according to our alphabet, and I believe that, considering the short time that I could spend among the [Indians], I had begun to speak their language easily and to understand it.”[22] Indeed, Father Marest was considered quite the linguist, but he was aware “that to learn one [language] without books and almost without an interpreter, among wandering people, and in the midst of several other occupations, is not the work of a day.”[23] Nonetheless, many colleagues spoke of Marest’s strong work ethic: “Dear Father Marest is somewhat too zealous; he works excessively during the day, and sits up at night to improve himself in the language; he would like to learn the whole vocabulary in five or six months. May God preserve so worthy a missionary to us.”[24]

As the experiences of all these Jesuit and Seminary missionaries attest, “acquiring indigenous languages required diverse efforts aimed at distinguishing sounds and choosing characters that could represent them.” For that matter, it was not just about being able to write the words but also about learning and understanding them including recognizing rules “to denote particular circumstances, arranging them intelligibly, and using them in socially appropriate ways.”[25]

Unfortunately, Marest’s Illinois-to-French dictionary is not known to have survived. And though his dictionary was likely not useful for a Frenchmen trying to learn Illinois, for Marest, as with Gravier discussed earlier, it was instead “rather for listening and understanding,” demonstrating that for the Jesuits, “learning language was not simply about introducing new ideas into the Illinois’s culture, but about fundamentally being able to understand the language in all its complexity.” Consequently, Illinois to French in construct suggests a “passive listener, struggling to understand” but longing to comprehend what he has heard.[26]

Examples of Texts Developed by Jesuit Missionaries and Others

Jesuit missionaries developed written forms of Native language to assist with conversion and communication and to help them preach and teach the Gospel to the communities within which they worked. Officials and missionaries sought to impose “their faith, their social practices, and their political order” through the Native tongue, but not to give Native Peoples a writing system.[28] Just as with maps in chapter five, these written texts could not have been written by missionaries or others alone. The French had to rely on Native speakers—Marie Rouensa among the Kaskaskias, for example—to help create the various documents they produced. Indeed “the individuals…who met in these language encounters and acted as intermediaries produced a wealth of Native-language texts,” even if they did not hold pen in hand. As such, “indigenous ‘assistants,’ therefore played crucial roles in shaping Native Christianities.”[29]

Some benefit remains from the Jesuits’ work. For one, they preserved the kinship system of the Illinois language. Indeed, so early is the data provided by the missionaries that “it is highly unlikely that the [kinship] system had yet been influenced by the European systems of French or English.”[30] And of course, their efforts at recording the Illinois language continue to allow linguistics to create materials in Illinois language to help teach new generations of Illinois language learners. While one could easily describe Native peoples as co-creators of the various texts produced, they were not necessarily free to create in their own right; they were not encouraged to use this strategy to write their own texts.

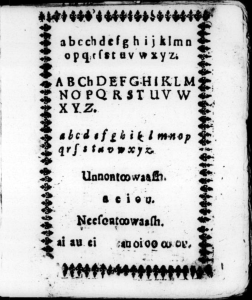

In sharp contrast, some in the English colonies did develop alphabet-based Native language materials and taught Native peoples to read and write in their own language. This began in the early 17th century when William Wood created a list of Massachusett words so to provide readers “a sample of language not only as a curiosity, but as a set of labels for significant landscape features, rulers, and everyday objects…”[31] With time this modest beginning led to larger texts that culminated in written language in a Native community’s tongue. Soon enough, missionaries and preachers such as John Eliot sought to expand beyond English consumption and provide the Native peoples the ability to read and write in their own Native language.

Eliot himself believed that “true conversion required intense personal study of scripture,” and that any conversion that occurred “would be more likely to take place if achieved within the context of native family and community and through the medium of the native language.”[32] In 1650, Eliot expressed his desire “to teach them all to write, and read written hand, and thereby with pains taking, they may have some of the Scriptures in their own language,” but eventually in English as well.[33] One book widely used was Eliot’s Indian Primer (1687) which was designed to help Native children develop literacy and hopefully turn towards Christianity. As this strategy spread throughout the region, by the late seventeenth century, some 30 percent of the Massachusett-speaking people such as the Wampanoag could read and write. Young and old alike learned in school houses or while employed by white families.[34] As Native individuals learned the writing process, they in turn taught hundreds of others to do the same.

With time, Native nations in the East created their own texts that preserved the elegant discourse style mentioned earlier.[35] Some of these texts bring out dialectic diversity, very much counter to the “widespread linguistic homogeneity” that some believed developed because of the common written language.[36] These Native written texts demonstrated the perseverance of Massachussett despite significant contact with the English. With the Massachusett writing, “the elegant structure and phrasing of natives’ writings amply demonstrate the ‘lofty’ and sophisticated quality of their rhetoric,” that the Massachusset “were long resistant to the imposition of colonial authority, and the surviving writings by native speakers are eloquent testimony to the persistence of the Native voice.”[37] Ultimately, teaching Native peoples to write in their own language supported not only the recording of documents, laws, history and communication but also perseverance of their language, delivery style and culture.

As Europeans began to record languages, phonetically or otherwise, Native peoples may have found great fascination, indeed awe with the odd characters placed on the page. Indeed, without words for “paper,” some like the Ojibwe used traditional Native terms such as masinaigan (birch bark scrolls) to reference books. Even more cleverly, the Cherokees referred to paper writing as talking leaves or Utalotsa Woni. But wholesale awe at European writing is a huge assumption. Afterall, as we have seen in this text, Native groups had long pursued their own various writing systems through such means as pictographs, petroglyphs, hieroglyphs, winter counts. As Peter Wogan wrote: “There is not a radical disjuncture in the principle of graphic communication underlying the French [or English] alphabetic script and the various pictographic systems used by Native American groups…there are [many] instances of Native American pictographic messages that conveyed novel information between parties physically separated from each other.”[38] And from the period itself, one Jesuit missionary remarked, “they understand each other by figures as we understand each other by our letters.”[39] Thus, while some Native nations may have been initially “wowed” by French writing, or may have come to see how it was effectively used, others saw it as a distraction from the daily needs of self and others. As the Jesuit Father LeJeune lived among the Montagnais, not only did they seem unimpressed with his skills of reading and writing, they were “astonished at the value we place upon books, seeing that knowledge of them does not give us anything with which to drive away hunger.”[40] LeJeune, in fact, had to rely on the Montagnais for sustenance. He was useless as a hunter, and contributed few food supplies to himself much less the nation. To the Montagnais, time could have been better spent hunting and gathering rather than reading and scratching marks on paper.

Exposure to a new way of communicating was likely initially exciting. The early seventeenth century Englishman, James Rosier “picked up ‘names of divers things’ after trade had concluded for the day, and ‘when they perceived me to note them downe, they would of themselves, fetch fishes, and fruit bushes, and stand by me to see me write their names.’”[41] One French Recollet missionary by the name of Gabriel Sagard, commented that the Huron even equated his style of writing with snowshoes. As he learned new words among them, they would say to him “Assehoua, Agnonra, Seatonqua…” or “take your pen and write.” Quite literally, however, they were saying “bring snowshoes and mark it,” much like snowshoes would make impressions in the snow.[42]

Nonetheless, some Native people understood the importance of written communication nonetheless. On the Mississippi, as the Seminary missionary François de Montigny and his men continued toward the Gulf Coast, they arrived among the Houmas not too far from modern day Baton Rouge, where the Native peoples handed the French entourage a letter written by Iberville. They had taken good care of the precious letter that documents the Canadian’s arrival in the region by 1699.[43] And with time, some embraced the importance of written communication whether they understood it or not. The Quapaws considered reciprocity, the exchange of goods and full participation in the calumet ceremony as their form of the “word” of commitment, relationship, friendship. But as colonialism evolved into Americanism, the Quapaws had to rely on the written word, an otherwise foreign concept to them. Words written, in some instances, indicated a change away from Native traditions to American ones. Though under normal circumstances the Quapaws celebrated the calumet with any Europeans who entered their village, when the Americans took over, the calumet ceremony was disallowed. As treaties were formed, particularly in the early 19th century, the signing of the document took center stage, not the calumet ceremony. Consequently, the Quapaws kept copies of treaties close at hand, viewing “the written treaty as sacred,” the new form of agreed upon alliance and reciprocity.[44] And yet, some had unfavorable views of an alphabetized treaty, especially once it became known that scribes deliberately falsified agreed upon words in council. Thus, “when two groups disputed what had been agreed to at an earlier meeting, some Native people refused to acknowledge the authority of a written document, precisely because of its taint by association with Europeans. Having no need for writing, and relying instead upon wampum belts as records, Lauurance Sagourrab (Penobscot) considered it their ‘Indian distinction.’”[45]

| Quapaw Treaty of November 15, 1824, Arkansas State Archives. Click on each image to see an enlarged version. | ||

|

|

|

19th century Writing

As Americans pushed westward and laid claim to millions of acres of Native lands, Native communities along and near the Mississippi River began to develop or embrace written forms of communication with distinct goals in mind. The Choctaws, for example, were a very literate people by the late 1800s with well over 11 million pages of written materials published before the Civil War. Some of this included textbooks written for the new schools developed under the direction of the Choctaw nation. Indeed, by the late 1800s, the Choctaws boasted a 90% literacy rate among their peoples with some 176 schools under its extensive educational system. This written literacy and educational advancement begun in the 1820s with the help of a Presbyterian missionary named Cyrus Byington led to official records of the Choctaw nation being preserved through Byington’s Choctaw orthography. But what was particularly vital for the Choctaws was that developing reading and writing skills in Choctaw and English helped to support religion, governance as well as formal education. By 1826, they had their first written constitution and made various amendments to it over the course of the 19th century.[46]

Choctaw Academy, established in Blue Spring, Kentucky in 1825 as a collaborative effort between the nation and the American government, sought to provide Native schooling to students from a diverse group of Native nations including Cherokees, Chickasaws, Miamis, Quapaws and Osages. While many did not wish to see their children attend this school, others did including one Potawatomi chief who exclaimed: “I wish our children to be instructed like the whites; then these educated children will become capable of assisting us in the transaction of business with white people.”[47] This secular school, the first not run by a religious group, proved more appealing for those who wished for education without Christian overtones. Consequently, students enrolled in this school “progressed from spelling and orthography to reading and writing, while intermediate students learned grammar, geography, basic history, surveying, Italian bookkeeping, and algebra, and advanced students took on moral philosophy, astronomy, Latin, and classical history.” By 1848, though Choctaw academy had graduated over 600 students from seventeen different Native nations, its doors were shuttered due to poor living conditions, poor food, epidemics and racial tensions.[48]

With time, the Choctaws began to publish their own books. Though they initially had to rely on publishing companies in places like Boston and Cincinnati, by the 1840s, the Choctaws and other Native groups such as the Cherokees and Shawnees, owned and operated their own printing presses not only in support of their own language materials but for other nations as well. Snyder tells us that the Choctaw press housed at Doaksville published the earliest copies of the Choctaw Telegraph in 1848. This bilingual weekly newspaper, edited by Daniel Folsom “featured local, continental, and global content, plus financial coverage, literary sketches, and more.” The linguistically related Chickasaws also published a newspaper, the Chickasaw Intelligencer, with Choctaw Academy alumnus Jackson Frazier as its editor. This newspaper was “a weekly devoted to ‘Science, Literature, Agriculture, Education, and the advancement of the Arts and Manufactories, among the Chickasaws and other civilized tribes…’”[49] And with time, many other newspapers arose among Native nations including the Free Press (1878) among the Caddos, the Osage Herald (1875) and the Cheyenne and Arapaho Carrier Pigeon (1910). These and many others “served as general interest publications, offering community information and advertising, while at the same time playing the role of watchdog and crusader.”[50]

The Cherokees

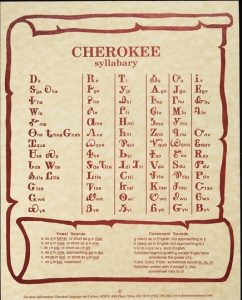

Missionaries recorded language and attempted to communicate the gospel to Native peoples while also preserving the language so that they-the missionaries-might better communicate orally as well. The Jesuits in particular created the systems; they used phonetics and wrote in alphabet form. But while Protestant missionaries freely shared writing with Native peoples along the East Coast, this was not the case with the French Jesuits to those who lived along the Mississippi. Some, therefore, chose to take matters into their own hands. The great Cherokee, Sequoyah-George Gist or Guess-, a monolingual speaker of Cherokee, “without links to Christianity or to Euroamerican schooling,” created the best known, most widely used written language for a Native American community, the Cherokee Syllabary, the first Native-created writing system that was applied to the Cherokee language in the 19th century.[51] Unlike the missionaries who used the roman alphabet, Sequoyah created Cherokee written language in syllabic form that was, for the most part, “enthusiastically embraced both by those Cherokees who had moved west [into Arkansas] to avoid further conflict with white fontiersmen and by those who had stayed in the east and asserted their right to continued self-government.” Overall, the creation of the syllabary served as “a key element in the maintenance of Cherokee social boundaries and ethnic identity.”[52]

In the early 19th century, Sequoyah, who only spoke Cherokee, sought a way to communicate in his language in written form. He first attempted a pictographic or perhaps hieroglyphic system as early as 1809 but by 1821 had an early iteration of the syllabary in place. As the story goes, he relied on his daughter, Ahyokeh, a young six-year-old to help demonstrate the value of the syllabary to others. Not long after, the use of the syllabary spread throughout the Cherokee nation and by October 1824, a great number of Cherokees could read and write in Sequoyah’s language. And though not all Cherokee individuals learned to read syllabary, by the 1830s, and despite separation into different regions of the south, “Cherokee literacy was widely diffused and…virtually every non-literate Cherokee had access to Cherokee readers in his [or her] own settlement, if not in his [or her] own household.”[53] Indeed, the 1835 census suggests some 43 percent of all Cherokee households had one member who could read Cherokee syllabary.

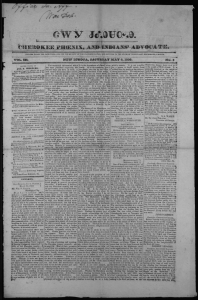

Though there was widespread use of the syllabary before 1827, there are no known surviving documents written by hand prior to type cast of syllabary for printing. Nonetheless, historic writing remains. Samuel A. Worcester, a missionary from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, understood the value of the syllabary for helping teach Christianity to the Cherokees. Thus, he sent the syllabary to Boston for casting into type so that one could begin to publish in written Cherokee (also known as Sequoyan) language. Once the syllabary was prepared for printing, it soon promoted widespread access to stories, letters, Christian writings, Cherokee laws, indeed a newspaper, The Cherokee Phoenix, founded on February 21, 1828. This weekly newspaper provided such things as news, writings in English and syllabary, and crucial points of information important for the Cherokee nation as a whole.

Elias Boudinot, the first editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, raised funds throughout the East Coast to help fund the paper. Once under way, the newspaper “portrayed the standards of Cherokee civilization, discussed problems and politics, and reflected the most persistent issues of Cherokee life.” It also informed people about the federal government and the removal of Native peoples from ancestral lands to the Indian Territory.[54] Worcester became a regular contributor to the Cherokee Phoenix and collaborated with the editor, Boudinot, in translating and printing Bible chapters and hymns for the Cherokee people.[55]

Since the first printing of The Cherokee Phoenix in 1828, the syllabary system has remained virtually the same. But some characters did change and some believe that this was primarily at the hand of Sequoyah himself. As Walker and Sarbaugh report, “several of his contemporaries reported that Sequoyah experimented with different forms of syllabic characters…to make these characters more comely to the eye….[or to make ] an alphabet for the pen (that is for speedy writing)…”[56] Indeed, the seemingly Roman characters present in the syllabary may have a history of their own according to U.S. Army Captain John Stuart:

“Being one day on a public road, [Sequoyah] found a piece of newspaper, which had been thrown aside by a traveler, which he took up, and, on examining it, found characters on it that would be more easily made than his own, and consequently picked out for that purpose the largest of them, which happened to be the Roman letters, and adopted in lieu of so many of his own characters—and that, too, without knowing the English name or meaning of a single one of them. This is to show the cause and manner of the Roman letters being adopted.”[57]

Despite its fame and popularity, there were some who did not want the Cherokees to use the Sequoyan writing system and perceived the syllabary as a “threat to European dominance.”[58] Consequently, some missionaries and federal agents continued to promote their preference for English literacy and an alphabetic-based form of Cherokee as developed by John Pickering and David Brown, a Cherokee who attended Andover Theological Seminary.[59] Pickering had developed a “uniform orthography, while Brown assisted him in alphabetizing Cherokee so to potentially bring literacy to the Cherokee people.[60] The language system that Pickering and Brown created was ready for publication and use by 1825, but the proposed alphabetized Cherokee system was never completed since the syllabary became the prominent written language. Indeed, as the popularity of the syllabary fully took hold, “Pickering’s system was abandoned.”[61] Pickering boldly stated:

“I should inform you that this native, whose name is Guest, and who is called by his countrymen ‘The Philosopher,’ was not satisfied with the alphabet of letters or single sounds which we white people had prepared for him in the sheets of a Cherokee Grammar formerly sent to you, but he thought fit to devise a new syllabic alphabet, which is quite contrary to our notion of a useful alphabetic system…This is much to be regretted as respects the facility of communication between these Indians and the white people; and the plan seems to us to be very unphilosophical…So strong is their partiality for this national alphabet that our missionaries have been obliged to yield to the impulse and consent to print their books in future in the new characters.”[62]

Clearly Pickering was annoyed that things had not gone his way; that he lost control of the Cherokee language. Now, to convert the Cherokees, missionaries had to learn to read and write in Cherokee syllabary. The Cherokees “simply would not accept another form of writing, so the missionaries had to comply with their wishes.” Ultimately, “the syllabary certainly transformed the Nation in ways that supported and preserved Cherokee culture and traditions.”[63]

But there were also some elites among the Cherokee nation who were favorable to assimilation and thus were reluctant to embrace this non-English form of written communication. Indeed, some, including his wife and friends, suspected Sequoyah of witchcraft, that he was using “improper spells,” that is “ones used not to heal but to harm, spells that are not used within the accepted bounds of the society.” Thus his friends “dissociated from him and regarded the syllabary with suspicion.”[64] Sequoyah tried to show the practical implications of the syllabary, that it was not some form of magic, wizardry or even sorcery. Regardless, he eventually “allowed his people to think of it as connected to spiritualty.” Ultimately, the syllabary was accepted “as a gift from the Creator—a gift that, if used wisely, could help the Cherokees to both maintain traditional spiritual beliefs and combat removal. And that is exactly how Cherokees used the syllabary.” As this writing system spread, “Sequoyah became at once school-master, professor, philosopher, and a chief. His countrymen were proud of his talents, and held him in reverence as one favored by the Great Spirit.”[65]

The syllabary was much more than just a way to write Cherokee language. For one, to try to curtail white encroachment on their homelands, Cherokees “needed to learn to use non-Indian weapons.”[66] While ultimately unsuccessful at stopping Cherokee removal, it did serve “as a symbol of ‘civilization’ and ingenuity in Cherokees’ public relations campaign against removal.”[67] Further, its many uses abounded and remain to this day including a significant numbers of medicine books filled with incantations written in syllabary. Indeed, this particular content “was the main rationality that the missionaries employed in their rejection of the syllabary. As John B. Davis writes, missionaries ‘objected to Sequoyah’s alphabet because of its Indian origin and the fact that it was being used by conjurers in heathen incantations.’”[68] Thus, the syllabary served as “an agent of cultural preservation,” but also ensured perseverance of the language and Culture as a whole. Ultimately, “syllabary became an emblem of Cherokee pride, and more.”[69]

Part of the challenge of understanding Sequoyah and the syllabary is that so many unfounded facts have been published on the life of this man and his work. As stated by Fogelson, “the scarcity of reliable documentary evidence makes the task of piecing together the facts of Sequoyah’s life reminiscent of the quest for the historical Jesus.”[70] Perhaps Rose Gubele, a member of Cherokee nation, has provided us with the best manner to examine Sequoyah – through the Cherokee term duyugodv or truth. This Cherokee word “is the kind of truth that transcends facts…the kind of truth that we hear in our stories, the ‘moral’ of the story, which isn’t dependent on verifiable factual information.” What with all of the misinformation that exists about Sequoyah and his syllabary, Gubele states: “The only important fact is that no story, oral or written disputes that…Sequoyah brought the syllabary to the Cherokee people.” It is Sequoyah who “gave us a precious gift, one that as immense cultural implications. The syllabary was used as a vehicle for cultural preservation during the Trail of Tears and beyond; it was, and is, used to transmit and disseminate spiritual texts, and it has been used to create and encourage the production of a body of national literature.”[71] The truth? The duyugodv? Sequoyah, “had a strong connection to his culture” no matter who one tried to make him out to be. Sequoyah strongly believed the syllabary could bring far more independence from whites to the Cherokee peoples. To the point, culturally, Sequoyah “was Cherokee, and that is what is most important. Whether he had a white father or grandfather is irrelevant; he was ‘All Cherokee.’”[72]

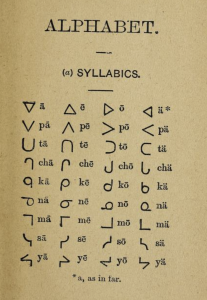

Cree Syllabary

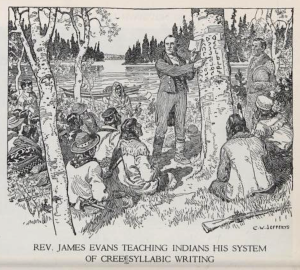

by Jefferys, Charles W. (Charles William), 1869-1951. 1942. volume 3 page 58.

While the Cherokee syllabary is quite infamous, far less known is the syllabary created in the 1830s by a Wesleyan Methodist missionary by the name of James Evans. This Protestant minister had learned of Sequoyah’s Cherokee syllabary and hoped to apply such a system to the Cree or Ojibwe language. Evans had originally attempted to write the Cree/Ojibwe language phonetically with the roman alphabet. But knowing of the success of the Cherokee syllabary, chose a more character-based, syllabic system and thus the creation of the Cree syllabary by 1840. The 1841 publication of a hymn book in Cree syllabary soon led to the widespread acceptance of the syllabary by the Cree and Ojibwe. And because Evans used birchbark to teach the language to the Nations among which he served, he became known as the man who could make birchbark talk.

Unlike Sequoyah’s syllabary that contains some 85 characters, the Cree syllabary only contained 9 but with four variations for each character, each at 90 degree variations to thus support some 36 different sounds present in the Cree language. This syllabary has been used since the 19th century to write manuscripts, letters, and personal records. In more modern times, the creation of Cree syllabic typewriters and the advent of computers has given even more control to Native speakers of Cree and has also allowed the use of this syllabary to continue in schools, through newspapers, and also within official documents.[73]

Alternative French and American Writing Systems

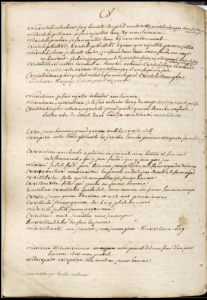

Politics of the French Colonial period on the Mississippi at time placed leadership into the position of writing in secret code. Governor Louis Billouart de Kervaségan, Chevalier de Kerlérec was one such individual who wrote in secret code primarily between April 1752 and February 1763 to thwart the ability of the English to read French dispatches that discussed colonial defense during the Seven Years’ War (1756-63). While some letters were sent to and from France on board ships, caretakers of letters were instructed to simply “throw the packets into the sea” when threatened with hostile takeovers. Thus, messages could go undelivered and thereby disrupt important communication necessary for the protection of the small Louisiana colony.[74] To better secure sensitive pieces of correspondence, an added level of protection through coded messages or encryption served to protect dispatches of military or diplomatic importance and thus prevented the need to nautically dispose of these texts. These “cipher letters” contained rows of numbers, each ending with a period, some with one or two or three digits. Once the coded letter reached its destination, be it France or Louisiana, a “cipher clerk” decoded or deciphered the letter into alphabet-based text so that those to whom it was sent might read it.

As it worked, two separate code books assisted the process. One code book provided the alphabetized list of words, letters, word fragments. This was the table à chiffrer. The second code book provided the code numbers in order with the words, letters, word fragments then listed. This was the table à déchiffrer. Thus an encoding and decoding process to write and decipher the document. But to render decoding even more difficult for the unwanted eyes, some letters had duplicate numbers that could be alternately used; some words could be spelled out as single words or broken up into their syllables. No spaces were indicated, nor were punctuation marks, capital letters and the like, thereby rendering the text that much more difficult to decipher.

Though Kerlérec’s code book no longer exists, in 2008, Donald Pusch graced us with his article on Kerlérec’s letters by providing a deciphering code that allows us to now read these coded texts. With the help of C. David Lodge and the development of a software filter, a deciphering code soon emerged that can be used to help us read texts relevant to the history of Governor Kerlérec’s term, his interactions with Native communities and his strategies and concerns for the Louisiana colony. Unfortunately, this code would not apply to others who may have used secret code in their documents. Thus, such a process was non-transferable and only usable by those who made direct use of its secretive characters. But this coding system was not immune to error. As Pusch points out, in an October 21, 1757 letter, Kerlérec described work done at Fort Ascension. The decoded version remarked that the fortress had been “reinforced with stone.” But the actual coded text states that the fortress had been “reinforced with pickets,” a severe contrast in material and stability going forward. Another example can be found from January 28, 1757 when a decoded letter stated “If the Abnakis keep their word with us, I shall be much more embarrassed.” The coded letter however did not reference the Abnakis but the Cheraki or Cherokees.[75] Despite errors, Pusch does state that the code seems to have served its purpose, to protect Louisiana from the English. For on July 13, 1759, a coded letter announced that the Balize post at the mouth of the Mississippi River had all cannons removed except for the two used for signaling. This suggests that “the fact that the English failed to exploit this and other such vulnerabilities may be due, at least in part, to the effectiveness of Kerlérec’s cipher.”[76]

Jefferson also designed what is called a “cipher wheel” or “wheel cipher” or even a “Bazeries Cylinder” that would also allow one to write in secret code. Here is a link to a website that lets you try it out in a digital form. Though Jefferson designed it, it does not appear that he ever built. Nonetheless, others did take his idea and created various forms of this wheel to send coded messages. Indeed, it was utilized by military personnel from 1922 to the beginning of World War II.

Conclusion

As the years continued, curious individuals began to collect words of many languages so to chart their diverse nature across the continent. Collectors pursued robust lists so as to compare words for similarities in structure, sound and meaning. Thomas Jefferson himself asserted the need to gather linguistic information on Native peoples since “knowledge of their several languages would be the most certain evidence of their derivation which could be produced.”[77] Thus when one found similarities within these lists, this led researchers to believe this as evidence for a genealogical link between the compared cultures and languages. Indeed, “if Hebrew cognates were found, all the better!” This essentially meant that these early researchers’ findings were “in tune with God’s revelation.”[78] Because of Jefferson’s efforts, today, you can access many of these lists of words through the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. But word lists were questionable, particularly their phonetically written forms which were based on pronunciation and phonetics of the recording culture (French or English, for example). Ultimately, this frustrated those who attempted to analyze, further record, or even speak the language.[79] While many sincerely sought to better understand Native languages, others had more sinister goals in mind. Many Native peoples came to suspect that the study of their languages was a “wicked design upon their country.” Indeed, some 19th century language researchers and groups such as the War Department studied Native languages so as to identify alliances and differences and determine their implications on Christian conversion or assimilation within the growing American landscape. As differences emerged, the Federal government sought to exploit them, to establish control over Native communities, and to play Native communities against one another in land cession treaties. They intended to affirm, in their minds, that “Native languages and Native minds were as ‘savage’ as popularly imagined.”[80] But no one could ever take away Native perseverance in learning to read and write either phonetically or syllabically. Indeed, as Cushman points out, Sequoyah quite literally turned European notions of literacy on its ear:

“Sequoyah ruptured the colonial work of literacy, that is, reading and writing with the letter, by developing a completely unique system of writing that codifies Cherokee language and logics….Because it was intentionally made without reference to the alphabet, along the instrumental logics of Cherokee designs and language, the invention of the Cherokee syllabary denaturalizes the concept of literacy. Using the basic logic of letter-sound correspondence, Sequoyah invented a system that had absolutely no letters in its original script. This invention, from its very creation, denaturalizes the conceptual fields of civilization, humanity, and knowledge associated with what it means to be literate, even as it appears to be complicit with these forces…[Sequoyah’s] invention was the initial rupture that changed the terms of the conversation about what it meant, indeed what it means, to be literate, thus ‘civilized’ and ‘fully human.’”[81]

Questions

Ponder these questions:

- Why do you suppose the English were far more willing to instruct the Native peoples of the Northeast in reading and writing in their Native language? Why did the Jesuits not do the same? Did religion play a part in this decision?

- The Library of Congress has a tremendously valuable collection of North American newspapers dating back to the colonial period. This collection includes newspapers created by the Cherokees, the Choctaws, and any number of other Native nations. Using this link, select two different Native newspapers and spend some time reading a page or two of each. Be prepared to share your information with your classmates including the title of the newspaper, the edition and date, and the substance of the stories or items you read or noticed.

- Visit the Jefferson Wheel Cipher website, follow the instructions on the site and create a coded message for your classmates to read.

- Elizabeth Hill Boone & Walter Mignolo, Writing Without Words: Alternative Literacies in Mesoamerica and the Andes, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1994), 15. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 191, 208. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 201. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 200. ↵

- Carayon, Eloquence Embodied, 82-84. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 201; LeClercq, Nouvelle Relation, 141-142 or LeClercq, New Relation, 131. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 196. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 192; Pierre Antoine-Simon Maillard, “Lettre de M. L’Abbé Maillard sur les missions de l’Acadie et particuliairement sur les missions Micmacques,” in Les Soirées Canadiennes (Québec, 1863) 3:409-10. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 198; Maillard, “Lettre de M. L’Abbé,” Soirées Canadiennes, 3:358-362. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 199; Maillard, “Lettre de M. L’Abbé,” Soirées Canadiennes, 3:359. ↵

- Christian Kauder, Buch das gut (Vienna, 1866). ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 206; Micmac Manual: Manual of Prayers, Psalms, and hymns in Micmac Ideograms: New Edition of Father Kauder’s Book published in 1866 (Restigouche, Québec, 1921; 3d ed., Ste-Anne-des-Monts, 1995), 1. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 190; David L. Schmidt and Murdena Marshall, eds., and translators, Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America’s First Indigenous Script (Halifax, 1995). ↵

- Carayon, Eloquence Embodied, 61-62; Jacques Cartier, Relations, ed. Michel Bideaux (Montreal: Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 1986), 224–226; Floyd G. Lounsbury, “Iroquoian Languages,” in Bruce G. Trigger, ed., Handbook of North American Indians, XV, Northeast, 334–343; Roland Tremblay, Les Iroquoiens du Saint Laurent: Peuple du Mais (Montreal, Que., 2006). ↵

- Bergier, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 50, p. 4 ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it well,” 627; Claude Allouez et al., Facsimile of Père Marquette's Illinois Prayer Book (Quebec: Quebec Literary and Historical Society, 1908). ↵

- Sean P. Harvey & Sarah Rivett, “Colonial-Indigenous Language Encounters in North America and the Intellectual History of the World,” Early American Studies 15, no. 3 (Summer 2017), 457. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 637, FN 51. ↵

- Michael McCafferty, “Jacques Largillier: French Trader, Jesuit Brother, and Jesuit Scribe ‘Par Excellence,’” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-), 104, no. 3 (Fall 2011), FN 16; Thwaites, "Marest to Germon, JRAD, Vol. 66, 245-47. ↵

- David J. Costa, “The St-Jérôme Dictionary of Miami-Illinois,” Papers of the 36th Algonquian Conference, ed. H. C. Wolfart (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 2005), 131. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 635-637; Thwaites, "Julien Binneteau," JRAD, vol. 66, 67-69; Thwaites, "Sébastien Rale," JRAD, vol. 67, 143; Thwaites, "Marest," JRAD, vol. 66, 245. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 638; Marest to Jean de Lamberville, 1706, in JR 66:117. ↵

- Galloway, "Talking with the Indians," 111. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marest to Lamberville, JRAD, vol. 66, 117; Thwaites, "Letter of Binneteau," JRAD, vol. 65, 71. ↵

- Harvey & Rivett, “Colonial-Indigenous Language Encounters,” 455. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 639. ↵

- Harvey & Rivett, “Colonial-Indigenous Language Encounters,” 467. ↵

- Harvey & Rivett, “Colonial-Indigenous Language Encounters,” 449. ↵

- Harvey & Rivett, “Colonial-Indigenous Language Encounters,” 456. ↵

- David J. Costa, “The Kinship Terminology of the Miami-Illinois Language,” Anthropological Linguistics, 41(1), (Spring 1999), 29. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 175. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 180. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 180; Henry Whitfield, A Farther Discovery (London, 1834 [1651]): 144. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 181. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 183. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 181 & 183. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 186. ↵

- Peter Wogan, “Perceptions of European Literacy in Early Contact Situations,” Ethnohistory 41, no. 3 (Summer 1994): 413. ↵

- Thwaites, "Rale to his Brother," JRAD, vol. 67, 227. ↵

- Thwaites, "Le Jeune's Relation, 1634," JRAD, vol. 7, 9. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 23; James Rosier, “A True Relation of the Voyage of Captaine George Waymouth, 1605,” in Early English and French Voyages chiefly from Hakluyt, 1534-1608, ed. Henry S. Burrage (New York: Scribner’s 1906), 371. ↵

- Gabriel Sagard-Théodat, The Long Journey to the Country of the Hurons, ed. by G. M. Wrong and translated by H. H. Langton (Toronto: The Champlain Society, 1939), 73. ↵

- ”François de Montigny to Saint-Vallier,” August 25, 1699 ASQ, Missions, no. 41, pp. 5-7. ↵

- Key, "Outcasts," 280. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 36. ↵

- Christina Snyder, Great Crossings, Indian Settlers and Slaves in the Age of Jackson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017). ↵

- Christina Snyder, “The Rise and Fall and Rise of Civilizations.” The Journal of American History 104, no. 2 (September 2017): 390, FN 11. ↵

- Snyder, “Rise and Fall and Rise,” 391. ↵

- Snyder, “Rise and Fall and Rise,” 406. ↵

- Sharon M. Murphy, “Native Print Journalism in the United States: Dreams and Realities,” Anthropologica 25, no. 1 (1983): 26. ↵

- Williard Walker & James Sarbaugh, “The Early History of the Cherokee Syllabary,” Ethnohistory, Vol. 40, no. 1 (Winter, 1993), p. 70. ↵

- Walker & Sarbaugh, “Early History,” 71. ↵

- Walker & Sarbaugh, “Early History,” 72. ↵

- Murphy, “Native Print Journalism,” 25. ↵

- Walker & Sarbaugh, "Early History," 88-89, FN 3. ↵

- Walker & Sarbaugh, “Early History,” 83. ↵

- Walker & Sarbaugh, “Early History,” 83; John A. Stuart, A Sketch of the Cherokee and Choctaw Indians (Little Rock: Woodruff and Pew, 1837), 22, note; Grant Foreman, Sequoyah (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1938), 39. ↵

- Rose Gubele, “Utalotsa Woni ‘Talking Leaves’: A Re-examination of the Cherokee syllabary and Sequoyah,” Studies in American Indian Literature 24, no. 4 (Winter 2012): 55. ↵

- Walker & Sarbaugh, “Early History,” 85. ↵

- Walker & Sarbaugh, 91, FN 10. ↵

- Gubele, “Talking Leaves,” 55; Susan Kalter, “’America’s Histories’ Revisited: The Case of Tell Them They Lie,” American Indian Quarterly 25(3) (2001), 333. ↵

- Gubele, “Talking Leaves,” 55-56; Kalter, “Tell Them They Lie,” 334. ↵

- Gubele, “Talking Leaves,” 57. ↵

- Gubele, “Talking Leaves,” 60-61. ↵

- Gubele, “Talking Leaves,” 61 & 66; Theda Perdue, Cherokee Editor: The Writings of Elias Boudinot (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996), 56 ↵

- Murphy, “Native Print Journalism,” 25. ↵

- Snyder, “Rise and Fall and Rise,” 392. ↵

- Gubele, “Talking Leaves,” 62; John B. Davis, “The Life and Work of Sequoyah,” Chronicles of Oklahoma 8(2) (1930), 169. ↵

- Gubele, “Talking Leaves,” 66. ↵

- Raymond D. Fogelson, “On the Varieties of Indian History: Sequoyah and Traveller Bird,” Journal of Ethnic Studies 2 (1974), 108. ↵

- Gubele, “Talking Leaves," 48-49. ↵

- Gubele, “Talking Leaves,” 57-59; Jack Frederick Kilpatrick and Anna Gritts Kilpatrick, Friends of Thunder: Folktales of the Oklahoma Cherokees (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995), 181. ↵

- John Nichols, "The Cree Syllabary," In Peter Daniels (ed.). The World's Writing Systems. New York: Oxford University Press (1996). 599–611. ↵

- Donald E. Pusch, “Kerlérec’s Cipher: The Code Book of Louisiana’s Last French Governor,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 49, no. 4 (Fall 2008): 464. ↵

- Pusch, “Kerlérec’s Cipher,” 473 see footnotes 23-26. ↵

- Pusch, “Kerlérec’s Cipher,” 475. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 2. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 311. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 17-18. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 2-5, 11, 17; Henry R. Schoolcraft, “Article V. Mythology, Superstitions and Languages of the North American Indians,” Literary and Theological Review 2.5 (Mar. 1835): 96-121, at 117. ↵

- Ellen Cushman, “Cherokee Writing: Mediating Traditions, Codifying Nation,” in Cathy C. Waegner, ed., Mediating Indianness (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2015), 99-100. ↵