6 Interpreters

Interpreters help us communicate with individuals who speak a language different from our own. Interpreters work locally, with police, hospitals and social workers. They work nationally and internationally through Customs, the State Department, the United Nations, as well as within business, industry and tourism. Interpreters are just as important today as they were throughout the colonial period. From the time of Cartier’s arrival in the early 16th century on into the 19th century, interpreters of any number of cultures helped Native peoples and the French communicate through words when possible.

As Marquette and Jolliet journeyed south to meet the Quapaws, they attempted to find an interpreter to help them verbally communicate with this Arkansas nation: “We embarked early on the following day [from the Mitchigameas], with our interpreter; a canoe containing ten [people] went a short distance ahead of us. When we arrived within half a league of the Akamsea [Arkansas], we saw two canoes coming to meet us.” Their hope was that the Mitchigamea man, whom they had recruited, spoke enough Illinois to help them interact peacefully in their first encounter with the Quapaws. But their confidence was quickly dashed as his language skills could not support their translation needs. Though signs quickly became their initial mode of communication, “We fortunately found there a Young man who understood Illinois much better than did The Interpreter whom we had brought from Mitchigamea. Through him, I spoke at first to the whole assembly by The usual presents,” another example of gifts as words. “They admired what I said to Them about God and the mysteries of our holy faith. They manifested a great desire to retain me among them, that I might instruct Them.”[1]

Along the Mississippi, the French often relied on interpreters who spoke the Illinois language to mediate communication between the French and many of those with whom they interacted. Jolliet, “a young man, born in this country [New France],” knew the Illinois language well enough to interact with others who could fluently interpret the language.[2] Even some 30 years after Marquette and Jolliet, Henri de Tonti also turned to an Illinois interpreter when he strove to convince the Chickasaws that he and Iberville longed for regional calm. Initially, de Tonti invited the Chickasaw chief to travel to the French fort at Mobile to secure a peace accord but the Chief refused to comply. Only after the Frenchman secured an Indian who spoke Illinois and could interpret from French to Illinois to the Muskogean language (a form of “chain interpretation) did the Chief became convinced of the legitimacy of de Tonti’s request. Eventually, the Frenchmen and several Chickasaws, Choctaws, Mobilians and Tohomés journeyed south to meet with Iberville. Once at Mobile, all were welcomed with food, gifts and desires for peace.[3]

Chain Interpretation was “a burdensome arrangement in which European explorers depended on several translators lined up according to their ability to speak with each other.” This form of interpretation quite literally went through three or four separate languages to get the message across. Ironically, Drecshel argues that “chain interpretation may have served Southeastern Indians as a form of passive resistance.”[4] That is, such a strategy made it more difficult for the French, English or Spanish to truly infiltrate Native communities and cultures.

Click on this link to see a comic example of this form of interpretation as acted out by Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz on their 1950s TV show “I Love Lucy.”

Communication through interpreters–of either European or Native origin–became more common as the years passed. Europeans hoped for “interpreters whose closeness to native culture gave them an intimate knowledge not only of native tongues but of the mental and moral codes for deciphering native acts, hopes, and fears.” But how one developed their second or third language skills to become an interpreter varied based on context. Early in the colonial process, some Native peoples were kidnapped and sent to Europe to learn French, English or Spanish so “to translate native words and concepts and to impress their fellow tribesmen with the invaders’ homegrown numbers and wonders.” As early as 1534, Cartier “purloined two of chief Donnacona’s sons” to develop linguistic knowledge and enhance their Christianity. But so too did kidnapping arise in the opposite direction. When Europeans were taken captive, some chose to remain with their captors, having developed kinship relationships with the people due to extended imprisonment. Alternatively, some captured individuals chose to return to their home but also to remain a link between Europeans and the Native peoples with whom he or she had lived. Indeed, some of the best European-born interpreters were taught by northeastern tribes after being captured during Euro-Indian conflicts. Louis-Thomas Chabert de Joncaire, for example, served as an interpreter between New France and the Iroquois in the 1680s after he was captured by the Senecas and subsequently adopted and married. He played a major role in the Franco-Iroquois peace treaty of 1701 and, with time, his two sons “succeeded him as accomplished interpreters, forest diplomats, and thorns in the sides of British officials.”[5]

Samoset, Squanto, Pocahontas and Sacajawea are four, well-known Native individuals who provided linguistic assistance between Native peoples and Europeans. Though Samoset was not kidnapped, he was rather adept with English language and customs, the result of long association with English speaking fishermen along the coast of Maine. Thus, one can imagine the reaction of the English settlers from the Mayflower when Samoset surprisingly walked out of the woods, marched up to the new arrivals, introduced himself and asked for some beer! Not too long after his encounter with the Mayflower settlers, Samoset introduced them to Squanto who had been kidnapped in 1614 by Thomas Hunt to be sold as a slave in Spain. Squanto managed to escape and found sanctuary in London with a merchant named John Slany. He returned to his village some four years later, fluent in English but deeply saddened by the loss of his people from an epidemic. Without a village or home, Squanto attached himself to the Plymouth Rock pilgrims and helped not only with practical matters but also in negotiating with other Native communities within the region.[6]

Matoaka, more familiarly known as Pocahontas, became an important linguistic liaison between her people and the English. When taken into custody by these Europeans in 1613, she was instructed in the Christian faith, baptized and then married to an Englishman, John Rolfe. Known from that point on as Rebecca Rolfe, Pocahontas, her young family and several others traveled to London to be presented at court. Another well-known woman named Sacajawea accompanied Lewis and Clark in their early 19th century exploration. The two explorers acquired the Shoshone woman from a French fur trader named Toussaint Charbonneau who joined their expedition. Charbonneau himself obtained Sacajawea from the Hidatsa who had enslaved her. During her time on the expedition, Sacajawea helped with negotiations, passage through difficult terrain, and access to sustenance along the journey. After her work with Lewis and Clark, it is quite possible that Sacajawea rejoined her Shoshone nation and served as an interpreter for her people for a number of years before her death.[7]

Sadly, when Native peoples were taken from their lands across the ocean to France, England or another European region, many struggled to survive. Disease, hunger, heartache, alcohol, any of these could impact their survivability in the old world and, once returned, in the new. Several of Cartier’s sixteenth century captives died in France before they could return to the Québec region. Pocahontas accompanied her English husband to London but died on her return trip to Virginia while still on the Thames River. And in the case of one Pierre-Antoine Pastedechouen, a young Montagnais boy who was sent abroad to learn the French language, he was “thoroughly ruined by his six years in France.”[8] When he returned to his Native village, he was fluent in French, Latin and the Gallic culture but had lost fluency with his own language. Absence had also taken from him knowledge of the lands and traditions important to his Native culture. His people were ashamed, Antoine ostracized. He died of starvation in the woods–lost to his people and of little use to the French.

Alternatively, some Native children were schooled quite near their Native communities. The first bishop of Québec, François de Laval, purchased various lands throughout the region, including Ile d’Orléans and Ile Jésus, to help with the establishment and maintenance of the Séminaire de Québec.[9] Frenchification was not met with great enthusiasm in Québec neither among the French nor the region’s Native peoples. With time, the Native children abandoned this form of education and enculturation since they and their classmates preferred to fish and hunt rather than to learn French grammar![10]

Another way of developing interpreters was to place young French boys within Native villages. On Cartier’s third trip to Canada in 1541, he left two young boys with the Chief of Achelacy “to learne their language.”[11] As Samuel de Champlain established Québec in the early 17th century, he too placed many young French lads within allied Native villages with whom the French engaged in trade. The majority of these boys remained within their chosen villages two to three years while others remained longer: Jean Nicollet remained connected with Algonquins and Nipissings for ten years; Nicolas Marsolet lived among the Montagnais and Algonquins for fourteen years; and Etienne Brulé, among the Hurons for eighteen years. Many of these interpreters became “the eyes, ears, and tongues of the fur trade monopolists and civil governors.”[12]

But young boys placed in villages along the Mississippi and Gulf coast became interpreters for the French and Native villages more for military and religious service than for trade. When the Seminary priests descended the Mississippi in 1698, young boys accompanied them or were later added to their missions to learn the language so as to expand Christianity. And as he established the Louisiana colony in the early 18th century, Iberville himself placed several young, literate boys, aged fourteen or fifteen, among the Houmas, the Bayougoulas, the Natchez, and other Native communities so that they might learn the language and customs of the peoples. From a military standpoint, these cabin boys–young lads from naval ships or cadets of the French army–were each positioned within a village to help preserve peace, negotiate treaties or develop relationships. Saint Michel was one such cabin boy who served at Fort Maurepas in 1700. In March 1702, Iberville moved him to the Chickasaw territory to learn the nation’s language and to there serve as an interpreter. Saint Michel eventually returned to Mobile in 1705 and related accounts of Choctaw depredations against the Chickasaws. By 1706, he was listed on the official budget as “Interpreter of Chickasaw and Choctaw Languages,” and received 360 pounds a year for his services. That same year, several interns were on the payroll as well, receiving between 96 and 144 pounds per year each.[13]

Needless to say, young cabin boys quickly learned the languages and cultures that surrounded them and developed some understanding of the attitudes and expectations of their host nation. Some even went on to receive military pay as cadets or even as official interpreters, particularly if they had won the confidence of Native peoples. Indeed, a young 11-year-old boy named Massé, a survivor of the Natchez revolt of 1729, became a cadet since he had “a very good aptitude for the Mobile language.” As such, “official interpreters of ‘rank’ could command the Indians’ respect better than mercenary and dissolute coureurs de bois and traders.”[14] But placing too young an individual within a village could be problematic. Father Saint Cosme, for example, “needed a man who could take care of his cows and pigs…”[15] The surly priest did not want just anyone and indeed preferred a determined man, capable of “kicking an Indian out of his house if he became impertinent,” as it was “not at all agreeable that a missionary chase an Indian out with punches.”[16] The Parisian overseer, Henri-Jean Tremblay attempted to appease Saint-Cosme. He sent him a thirteen- or fourteen-year-old lad, much the same age as other cabin boys in the region, to both learn the language and assist the priest. But Saint-Cosme refused him, declaring the teenager too young.[17] In truth, a thirteen-year-old would have easily attained the language and could have greatly helped Father Saint-Cosme, but any younger and it would have “defeated the purpose, because they soon ceased speaking their first language,” and instead embraced the language of those among whom they lived. Ultimately, the Frenchmen’s best bet was to use young teens who developed fluency among a Native community while in their adolescence and “could potentially teach their own language and answer questions about it.”[18]

It wasn’t just young boys who experienced linguistic immersion. Adults did as well, particularly when placed in villages during the early years of Bienville’s Louisiana colony. So starved were the Frenchmen for food due to poor crops and low supplies that their only means of survival stemmed from Native help. Once placed in a village, their presence “supplied the opportunity for maturer men with aptitude and motivation to learn the languages of their hosts.”[19] Frenchmen also formed close relationships with Native women and in some instances married them, so that, as a part of this relationship, their wives might teach them the Native language and customs. Intermarriage was supported between the French and the Illinois to promote trade, but also to lift up interpreters within a community. Marie Rouensa, an Illinois Kaskaskian, married the Frenchman Michel Accault, a relationship that likely led both individuals and their offspring to become interpreters on some level.

Some adults learned a language through study or by purposefully immersing themselves within a village and interacting with the Native peoples. Nicolas Perrot is a prime example. He arrived in New France in 1660 with several Jesuit priests and journeyed with them into the Pays d’en Haut to interact with the region’s Native peoples. His exposure to numerous languages and cultures led to his fluency and vocations as interpreter, explorer and fur trader within New France for a number of decades until his death in 1717. Even Coureurs de Bois like La Violette and Charles Delaunay learned enough to interpret language between non-bilingual Frenchmen and Native peoples, in particular the Illinois and the Quapaws. As for their French colleague Jean Couture, he lived and served as an unofficial interpreter among the Quapaws for a time, but by the start of the 18th century was a turncoat, living and trading among the English, bringing Englishmen into French territory and interpreting for them as they traded with and attempted to coerce Mississippi nations to side with the English.

Trade and diplomacy had concrete, tangible vocabulary and terminology that allowed for both visual and verbal interpretation and communication. But Christian terms proved more difficult, forcing missionaries to rely on the services of others to attempt to interpret their religion. Some Frenchmen, such as the seventeen-year-old Michel Buisson de Saint-Cosme, brother of Father Saint-Cosme, were sent to the Native villages specifically to learn the language and to assist Seminary missionaries with their work. But Native peoples, particularly women, were far more relied upon to interpret meaning. Father Marc Bergier, priest among the Tamarois, had a hymn translated by some Tamarois women who sang it to him so to learn proper intonation and inflection. Father Saint-Cosme sought support through an Illinois woman from Pimetoui. She helped him until she was threatened by the Jesuits who were opposed to the presence of Seminary missionaries among the Tamarois. And the Jesuit Jacques Gravier likely relied on Marie Rouensa, among others, to help with his Christian vocabulary and teaching as well. Indeed, “if attracted to the religious ideas of the newcomers, some Indians volunteered their services not only as interpreters but also as tutors to missionaries, conveying the dramatic difference in the organizations of Native and European languages.”[20] And yet, frustrations lingered–the Native peoples and missionaries could not directly interpret the spiritual language of one culture with the other. As a consequence, “missionaries convinced themselves that Native languages, and perhaps minds, were deeply deficient,” with some naively suggesting that the Native peoples had no religion.[21] Poor interpretation of words and blind observations led to such short-sighted views of Native cultures.

Several Jesuit missionaries did become quite skilled with Indigenous languages. Indeed at the 1701 Great Peace in Montreal, four Jesuits along with the explorer Nicolas Perrot served as official interpreters at this event.[22] But priests had many a lesson to learn. “One Montagnais man repeatedly fed ‘vile words’ to the unwitting Paul LeJeune, ridiculing a missionary who seemed ‘haughty’ and a ‘parasite.’ During a winter’s lodging he heard, ‘at every turn…eca titou, eca titou nama khitirinisin, “Shut up, shut up, thou hast no sense.” Jean-Pierre Aulneau, an early 18th century missionary among the Crees added that “‘what little’ missionaries learned ‘has been picked up in spite of them.’ Conditions, talent, pride, and occasionally overt opposition conspired against even those clerics who wanted to learn Native languages.”[23]

Typically, the best French interpreters were given military rank and salary. Nicolas Perrot served as a military translator in 1667 within the Ottawa and Illinois regions. Farther south, the French fort at Mobile employed several military interpreters over its many years. Marc Antoine Huchet functioned as a colonial interpreter of Indian languages in the early eighteenth century, serving for the Company of the Indies within the Choctaw territory. With regional tenseness from the Natchez attack on the French in 1729, Huchet played a diplomatic role when sent to several Choctaw villages to recover numerous slaves that had been initially taken by the Natchez during their attack on the French.[24] Another interpreter, La Chauvinière, was fluent in the Iroquois language. However, his charge also placed him along the Mississippi where he served in the French and Chickasaw campaign of 1739-1740.[25] And the military interpreter, Joseph, an Apalachee Indian, was appointed interpreter of Indian Languages by the Council of Commerce at Mobile in 1720.[26]

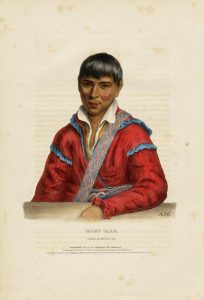

One military interpreter who stands out is François Sarazin, presumed father of Chief Saracen of the Quapaw nation. This Frenchman served as a cadet soldat and interpreter at Arkansas Post during the mid-eighteenth century. Sarazin was born in New Orleans, lived as a young lad on the Rue de Chartres with his parents and two brothers, but upon his father’s death (his father was an Indian trader), and the remarriage of his mother, the family moved to the resurrected Nachez Post where they remained for some seven years. Upon the death of her second husband, François’ mother, Anne François Rolland, married yet again and this time the family moved to Pointe Coupée, to the north of modern-day Baton Rouge. By this point, Sarazin was 13 years old and had lived among or had interacted with individuals of all walks of life, likely including the Choctaws, Houmas, Tunicas and Bayouguolas. In these different locations, François most certainly played with Native children and had ample opportunity to gain some semblance of Native language skills as a result. No doubt, with his different fathers engaged in trade, he was exposed to Mobilian trade jargon, a regional “second” language that eased communication between individuals who otherwise could not communicate through their first language. Consequently, by 1744, twenty years of age, François Sarazin served as a cadet soldat and interpreter at Arkansas Post.[27] Sarazin’s rank of cadet gave him greater standing with the Quapaws and helped him develop his skills as an interpreter. Unfortunately, any exact references to Sarazin serving in this capacity are lost to history, primarily because it was not unusual for one to omit the name of an interpreter during official activities. “Officers…often did not mention the names of individuals who lacked high military or social status in official reports and letters.” Nonetheless, Sarazin’s language skills, not to mention his knowledge of the Quapaws’ “attitudes, needs, and desires” assuredly proved essential in his efforts to support French and Quapaw activities throughout the region. After 18 years of service at the Post, Sarazin became a full officer, a Lieutenant Reformé who could lead troops into battle, all while maintaining his position as interpreter.[28] Sadly, his standing as an officer/interpreter was quite short lived. Somewhere around May 20, 1763, Sarazin was killed in a battle with the Chickasaws. A solemn mass was held for him on July 20, 1763 in one of his old childhood homes, Pointe Coupée.[29] After his death, his wife of 10 years, Marie Françoise Lepine, married Jean Baptiste Tisserant de Montcharvaux, the son of the post’s former commander. He too served as “officer and interpreter at this post.”[30]

Despite efforts to prepare or obtain solid interpreters whether Indigenous or French, concerns sometimes emerged over one’s reliance on Coureurs de Bois–“men who often drank and fought with the Indians and sometimes robbed them”–as interpreters rather than those more officially prepared for this important regional vocation.[31] Traders could certainly serve as interpreters, but the likelihood of thoroughly learning the language diminished because of their nomadic wanderings to and from trading posts. Nonetheless, these men represented the majority of those who could speak a Native language on some level. Since trade “did not require a highly sophisticated vocabulary or a punctilious command of treaty council protocol,” colonial officials made use of these men when necessary with demands that they attempt to improve their linguistic abilities. To do so, often, “they were assisted by native wives, and not a few were the métis products of similar unions themselves.”[32]

Serving as an interpreter proved difficult not just in terms of language but in terms of one’s acceptance within the particular culture at hand. Politics easily came into play, particularly when dealing with French and Native peoples’ policies, traditions, and laws. Ann Dubuisson describes one such situation in 1756 that was potentially politically complex for Sarazin:

“A French soldier garrisoned at the post killed another French soldier there and ran away. At about the same time, three other French deserters had been found and promised protection by some Ofogoulas Indians who brought them to Natchez, where that tribe had recently settled. The four French fugitives then took refuge in an Indian sacred cabin. As later explained by Guedetonguay, great chief of the Quapaws, whoever took refuge in this cabin where these Indians practiced their religion was absolved of his crime, and the man who was chief of the cabin would sooner lose his life than allow the refugee to be punished for his crime.” Consequently, the the Quapaw and Ofogoulas chiefs went to New Orleans to “claim pardon for the French soldiers” before Governor Kerlérec. To understand their argument, Kelerec needed an interpreter but “could not ask Sarazin or the interpreter from the Natchez Post. These men could not forcibly argue French policy, which would go against the established religious beliefs of people they worked amongst, without losing face or credibility.”

Thus, Kelerec chose Jean Baptiste Grevemberg dit Flament, a New Orleans merchant and a wise choice that “saved Sarazin from being placed in a compromising position, and the Quapaws could trust Grevemberg as an old friend” for he once served at Arkansas Post. As the meeting continued,

“the two chiefs begged for the lives of the men, though forgiveness of soldiers who deserted or murdered other French soldiers was absolutely contrary to French law. The Quapaw chief pointed out that his nation had been at war against the Chickasaws as a mark of affection for the French, and that his son had been killed and his daughter wounded. The governor answered that he was aware of the services that the chief’s nation had rendered but that he could not change the words uttered by the great chief of all the French. Chief Guedetonguay stood for a long time with his head bowed and then answered that if the Frenchmen were put to death, he could not answer for the dangerous attacks and rebellions that would almost certainly take place.”

As the proceedings continued, “the two chiefs finally stated that if these men were pardoned, they would give their word to hand over any future deserting soldiers or malefactors.” Finally, three years later, the council decided to pardon the men which left “an impression that perhaps the Indians, and not the French, were actually in control.”[33]

Throughout the French period (1673-1763), there remained a constant need for interpreters, be they soldiers, Native individuals, missionaries or even Coureurs de Bois. But the focus of interpreters would change. As things grew more complicated with the Spanish takeover of the French settlement in 1763, interpreters became even more invaluable since neither the Spanish nor the Native peoples had much experience with each other’s language or culture for that matter. In the spring of 1772, for example, the Quapaws showed their displeasure with the Spanish when presents went undistributed. Rather than accepting the blame for the lack of reciprocity with the Quapaws, the Spanish Commandant de Leyba “tended to blame French interpreters for turning the Quapaws against Spain.” As DuVal points out, “French interpreters were notoriously unreliable in promoting Spanish interests.”[34] Indeed, when French interpreters were hired to work with the Spanish, it went rather poorly for all concerned. A Frenchman named Montcharvaux “was not fit for the job [of interpreter], because he was very arrogant and disaffected from Spain.” Another named Landroni was soon found to be “’very disaffected from the Spanish nation,’ who was not telling the commandant the truth about what the Quapaws were saying and thinking, and was even mistranslating Leyba’s words to the Quapaws and theirs to him.”[35] La Bucière or Labuxière resided at French Arkansas Post but was fired by de Leyba for “speaking badly about the Spanish and consorting with the British.”[36] Still other interpreters appeared harmful for Spanish interests. Anselme LaJeunesse,“’a bad subject if ever there was one,’” lost the trust of both the Spanish and the Quapaws, and one Jean Baptiste Sossier “behaved himself very badly with the Quapaws and the whites of the Post alike.”[37]

But even as Arkansas Post and other posts and towns fell into American hands in the early 19th century, interpreters still played important roles. As Americans moved in, U.S. officials desperately needed individuals to provide information on a region’s Native peoples, to interpret in multiple languages, and to offer advice on regional Native protocol.[38] As the Quapaws were forced from their lands toward the Caddo region, the Frenchman Antoine Barraqué, assigned as sub agent for the Quapaws, served alongside Joseph Bonne, a Quapaw/Frenchman. Both helped to interpret for the Quapaw nation. These men, like several others, had gained their language skills by living among or near the Quapaws and engaging in trade with this great Arkansas nation.

Conclusion

The Mississippi River Valley and the Pays d’en Haut were multilingual. Far more often than not, when words were spoken, an interpreter communicated between linguistically different individuals. But Native peoples and Frenchmen did not serve as the lone regional interpreters. Numerous historical documents mention free and enslaved African men and women who worked as interpreters for both the colonizers and regional Native groups, likely due to their skills with the region’s European and Indigenous languages, as well as the Mobilian Jargon. Regardless of class or culture, when interpreters were used, one expected them to be as accurate and as sensitive to cultural nuances as possible. But the extent to which this occurred is difficult to determine. Trust was always an issue with interpreters, whether they were French, enslaved, or Native to the region. Did the interpreter faithfully interpret both sides of the conversation? Or did he or she relay what folks wanted to hear or what he or she wanted them to hear? Did one remain neutral as an interpreter or take sides? In many instances, we will never know.

Activity/Questions Forthcoming

What do you think?

- Sarazin and others served as interpreters at Arkansas Post. They spoke French, certainly, but to what extent did they speak Quapaw or any other language in which they interpreted? Did they speak the language proper or might they have spoken something else? Note: There’s not an exact answer here…but what do you think?

- In a quite infamous example from the southeast region of North America, Hernando de Soto and his Spanish entrada were greatly assisted by Juan Ortiz, a survivor of the Narváez debacle of 1528. This lost Spaniard had lived among Native peoples for some 12 years and had embraced not only their clothing and hair style but also the practice of tattooing. Fortunately for the Spanish, Ortiz had retained his native tongue and was able to assist them in their journey throughout the region. Unfortunately for the Spaniards, Ortiz died west of the Mississippi in March of 1542. So devastating was Ortiz’ death “that to learn from the Indians what he stated in four words…the whole day was needed; and most of the time he [the Indian interpreter] understood just the opposite of what was asked.’”[39] How do you explain this last comment? What led them to say this? What was likely taking place between the Spanish and the interpreter?

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 153-155. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 89. ↵

- “De Tonti to Iberville,” March 14, 1702, ANF, AM, Série 2JJ, vol. 56, 20. ↵

- David V. Kaufman, Clues to Lower Mississippi Valley Histories, Language, Archaeology, and Ethnography (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 67. See also Emmanuel Drechsel, Mobilian Jargon: Linguistic and Sociohistorical Aspects of a Native American Pidgin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 279. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 41-44. See also footnotes 70 and 71, page 44. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 218. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 217-218, & 223. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 42; see also footnote 67. ↵

- Between 1675 and 1681, two residences were built to house priests and students who attended the Petit Séminaire de Québec. This school, opened on October 9, 1668 at the request of Louis XIV and the Québec government, strove to instruct Indigenous and French children the French way so to “franciser” or Frenchify the Native children so that nothing would distinguish them from the French; so that ultimately they might intermarry and form a single united people, Ouverture du Petit Seminaire, October 9, 1668, ASQ, Manuscrit 2, Annales du Petit Seminaire, pp. 1s. Jean-Baptiste Colbert to Laval, March 7, 1668, ASQ, Lettres N, #27. Of the first thirteen enrolled, 6 were Hurons. Students in this school were distinguished from others by their blue cloaks covered in white ribbing, Noel Baillargeon, “La Vocation et les Réalisations Missionnaires du Séminaire des Missions Étrangères de Québec au XVIIe and XVIIIe Siècles,” Rapport Société Canadienne d’Histoire de l’Eglise Catholique 30 (1963), 39; Ouverture du Petit Seminaire, October 9, 1668, ASQ, Manuscrit 2, Annales du Petit Seminaire, pp. 1s.; Honorius Provost, Le Séminaire de Québec. Documents et biographies. Présentés par l'abbé Honorius Provost. Extraits de la Revue de l'Université Laval (Québec, 1964), 40. Of the students who were in the first class of the Petit Seminaire, two were twins – Pierre Volant and Charles Volant. Others included Jean Pinguet, Paul Vachon, J.-B. Hasley, Joseph Haondecheté, Joseph Honhateron, Joseph Hande8atiri, Joseph Dok8chiandes, Jean A8trou8ret, and Nicolas Arsaretta. Annales du Petit Séminaire; Amédée Gosselin, L’Instruction au Canada Sour le Régime Français (1635-1760) (Québec, Typ. LaFlamme & Roulx, 1911), 390. ↵

- Henri Têtu, Biographies de Mgr de Laval et de Mgr Plessis, Évêques de Québec (Montréal: Librairie Beauchemin, 1913), 35. ↵

- H. P. Biggar, The Voyages of Jacques Cartier (Ottawa: F. A. Acland, 1924), 257. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 46. ↵

- List of rations furnished to Fort Biloxi, May 25, 1700, ANOM, AC, C 13a, 1: 261–264; Muster roll for Fort Biloxi, May 26, 1700. ANOM, AC, C 13a, 1: 258; Jay Higginbotham, Old Mobile: Fort Louis de la Louisiane, 1702–1711 (Tuscaloosa: Univ. of Alabama Press, 1991), 80; Archives Colonials d'outre Mer, COL F1 A 13 f. 114v & 119v, 1706. ↵

- Patricia Galloway, "Talking with the Indians: Interpreters and Indian Policy in Colonial Louisiana," in Winthrop D. Jordan and Sheila L. Skemp (eds.), Race and Family in the Colonial South (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 1987), 115; See also Louboey to Maurepas, May 8, 1733, ANOM C13A, 17:232V; Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 47; see footnote 82. ↵

- “Saint-Cosme,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 35, p. 2. ↵

- “Saint-Cosme,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 33, p. 3. ↵

- “Tremblay, ASQ, Lettres N, no. 123, pp. 9-10; Tremblay, ASQ, Lettres N, no. 122, p. 16. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 225-26. ↵

- Galloway, "Talking with the Indians," 116. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 22. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 33. ↵

- Havard, Montreal, 1701, 43. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 28. ↵

- Minutes of the Council, August 29, 1716, ANOM, AC, C 13c, 4: 179. ↵

- "Bienville to Maurepas," MPA, I:452. ↵

- Minutes of the Council of Commerce, May 9, 1720, ANOM, AC, C 13a, 5:354. ↵

- Rolle General des Trouppes de La Louisianne commence en 1744, [1770], ANOM, AC, D 2c 54:n. p; List of missionaries, religious, and civil servants maintained in the colony, December 1, 1744, ANOM, AC, D 2d, 10:n.p. ↵

- "'Reformé' designated an officer placed on the payroll at reduced salary because the French military had need of or received applications for more officer positions than it could afford. A lieutenant reformé ranked above an ensign and was capable of independent authority, but technically he was junior to full-pay lieutenants. Reformés were paid about two-thirds of what regular lieutenants received." Ann Dubuisson, “François Sarazin: Interpreter at Arkansas Post during the Chickasaw Wars,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 71, (2012): 249-250, 259, FN 23. ↵

- ANOM, AC, D 2c 52:n.p. (list of October 28, 1762, later used to show death); See Full Certificate of Burial dated July 20, 1763, Archives, Diocese of Baton Rouge. ↵

- Alice Forsyth, Louisiana Marriage Contracts: 1728-1769, Abstracts from the Records of the Louisiana Superior Council, Vol 2 (New Orleans: Genealogical Research Society of New Orleans, 1989), 43. ↵

- Dubuisson, "Sarazin," 248-49 ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 48, FN's 86 & 87. ↵

- Dubuisson, "Sarazin," 257-59; "Indian Harangues at Council of War, June 20, 1756," Mississippi Provincial Archives: French Dominion, 5:173-178. ↵

- DuVal, "Fernando de Leyba," 19. ↵

- Arnold, Rumble, 92 & 93, see also FN 80. ↵

- “Revue des troupes en garrison aux Arkanças,” October 1, 1763, ANOM, AC, D 2c, 52:25; Stanley Faye, “The Arkansas Post of Louisiana: Spanish Domination,” The Louisiana Historical Quarterly 27, no. 3, (July 1944): 641-642; DuVal, “Fernando de Leyba,” 20; “Fernando de Leyba to Luis de Unzaga y Amezaga,” July 27, 1771, legajo 107, Roll 12, folio256, Papeles de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. ↵

- Arnold, Rumble, 88, 163; “Villiers to Gálvez,” September 15, 1779, AGI, PC, leg. 192:182; “Dubreuil to Miró,” October 15, 1785, AGI, PC, leg. 107:577. ↵

- Kathleen DuVal, “Indian Intermarriage and Métissage in Colonial Louisiana,” The William and Mary Quarterly 65(2), (April 2008), 296; Dorothy Jones Core, comp. and ed., Abstract of Catholic Register of Arkansas (1764-1858), trans. Nicole Wable Hatfield (DeWitt, Arkansas, 1976), 15, ("Marie, Indian") 40; "Treaty with the Quapaw," Nov. 15, 1824, in Charles J. Kappler, comp. and ed., Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties (Washington, D.C., 1904), 2: 210-11 ("Indians by descent," 2: 210); "Treaty with the Quapaw," May 13, 1833, ibid., 2: 395-97. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 41, 43-44. See also footnotes 70 and 71. ↵