2 Signs, Gestures and Body Language

Imagine – you have just arrived in a new country. You don’t have your bags, you don’t have a dictionary, you have no knowledge of the language. How do you communicate? How do you “say” I am thirsty or hungry? I need help? I need to find a bank? Where can I find a bathroom? European and Native nations faced similar struggles during the colonial period, without our modern technological and institutional functions listed. So how did they do it? How did they communicate in those first days and weeks of interaction? What did they “say”?

When Native peoples, French missionaries, soldiers and/or explorers first encountered each other, their key to safety and peaceful interaction was through effective communication. One needed information and had to find a way to some desired piece of knowledge. Given that Europeans were regional strangers, only the Native people could assist them with the location of natural resources; the paths to the west or south, to the north or east; the location of other Native peoples; where to find game, wild fruits, fresh water; how best to traverse the rugged terrain; when to plant and what to plant; whether one was willing to be friend or foe. Although communication through signs, gestures, body language involved a tremendous amount of tedious visual information, nevertheless they served as primary conversation tools early on. These visual modes of communication would be far more comprehensible than any words uttered in early interactions. One communicated not by saying but by doing. Ultimately, when Frenchmen asked questions through signs, Native peoples did their best to respond. But Native peoples had their own questions, and the French did their best to reply in kind. Both cultures soon realized that signs would continue to serve as a primary source for gaining information in the Mississippi River Valley and beyond even as individuals verbally spoke to each other.[1]

Native peoples certainly communicated with others long before Europeans arrived. All Native communities used sign language–hand gestures, facial expressions, physical touch and the like–with universal signs almost certainly in place, though perhaps with some signs more unique to a given nation. As Europeans arrived, Native peoples would use these same signs thereby “integrating the newcomers into their semiotic world through both words and nonverbal means.”[2] As Thomas Jefferson described it in the very early 19th century: “Almost all the Indian nations living between the Mississippi, and the Western American ocean, understand and use the same language by signs, although their respective oral tongues are frequently unknown to each other.”[3] Indeed, a somewhat standard sign language existed among the Plains Indians west of the Mississippi. As thousands of unrelated Native peoples were forced into “Indian territory,” Plains Indian sign language books increased in availability so that those entering this region (primarily Americans) might have some way of communicating with the different Native peoples encountered. Ultimately, signing could only take one so far. Concrete concepts–asking for water, saying hello, showing you come as a friend, locations and travel paths–were all relatively easy to sign and decipher. Alternatively, abstract religious, spiritual and ceremonial gestures proved far more difficult to convey and understand. Certainly, priests and Native shamans used gesticulations to communicate with their spirit world. But what did these mean to one who had no concept of the other’s spiritual and religious practices and traditions?

Signing was not a communication mode unique to Native peoples. The French also communicated nonverbally. In France, actors, prostitutes, sailors, priests, heretics, jesters, monks and many others used some form of gesticulation or signage. French sailors used signs to communicate from one ship to another. French monks used signs during periods of silence. There were, of course, individuals whose inability to speak forced them to use signs to communicate with others. Signing was a universal mode of communication, though not all signs were identical or similarly used from one community to the next.

Signs of First Encounters[4]

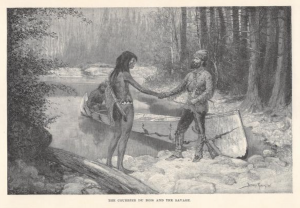

Jacques Cartier was the first known Frenchman to interact through signs with Native peoples. In one initial encounter, a Native person along the St. Lawrence River shore “made us many signs that we should return toward the said cape; and we, seeing such signs, gave orders to row toward him, and he, seeing that we turned back, began to flee and ran away ahead of us.” Here, a hand gesture–likely drawing the hand repeatedly towards oneself–was a way of saying “come towards me, towards the shore.” But when Cartier and his men did as asked, the physical response of the man fleeing from the banks of the St. Lawrence River communicated fear. To show they came in peace, Cartier and his men “landed opposite him and put a knife and girdle of wool on a rod for him, and then we went away to our ships.” These European gifts were meant to speak peace, nothing more. The metal knife and woolen material served as an introduction to French technology and a sign of good will rather than gestures of violence or confrontation.[5]

Cartier and the Native peoples had other first encounters that were far more complex and far more uncertain, albeit richly filled with signs and gestures. One day on the St. Lawrence, Cartier and his men caught sight of two fleets of Native canoes, with some forty or fifty boats and a large number of people who “made many signs that we should go ashore, showing us skins upon sticks.” Cartier and his men felt vulnerable and attempted to row away, but the Native peoples “prepared two of their largest canoes so to follow Cartier’s party….all came until near our said boat, dancing and making many signs, wanting our friendship, saying to us in their language: Napou tou daman asurtar, and other words which we did not understand.”[6] But because they (Cartier and his men) had only one longboat,

“we did not care to trust to their signs and waved to them to go back, which they would not do but paddled so hard that they soon surrounded our longboat with their seven canoes. And seeing that no matter how much we signed to them, they would not go back, we shot off over their heads two small cannon[s]. On this they began to return towards the point, and set up a marvelously loud shout, after which they proceeded to come on again as before. And when they had come alongside our longboat, we shot off two fire-lances which scattered among them and frightened them so much that they began to paddle off in very great haste and did not follow us anymore.”[7]

The next day, some of the Native peoples came in nine canoes to the point where Cartier’s ships laid anchored in a cove.

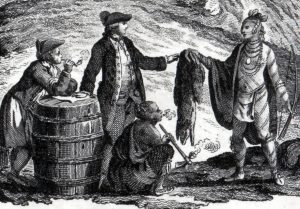

“And being informed of their arrival we went with our two longboats to the point where they were….As soon as they saw us, they began to run away, making signs to us that they had come to barter with us, and held up some skins of small value, with which they clothe themselves. We likewise made signs to them that we wished them no harm, and sent two men on shore, to offer them some knives and other iron goods, and a red cap to give to their chief. Seeing this, they sent on shore part of their people with some of their skins; and the two parties traded together. They showed a marvelously great pleasure in possessing and obtaining these iron wares and other commodities, dancing and going through many ceremonies, and throwing salt water over their heads with their hands. They bartered all they had to such an extent that all went back naked without anything on them; and they made signs to us that they would return on the morrow with more skins.”[8]

Peaceful, hopeful, frightened, uncertain, reassured–the Native people joyfully approached the French who, fear-filled, signaled to them to “stay back!” Shooting fire-lances and cannon resulted in fear and flight into the woods, and cautious vigilance from behind trees. Finally, signs of trade–holding up items and longing to exchange gifts brought some calm to an otherwise stressful scenario. These various greetings and interactions alone demanded careful interpretation since the tedious potential to interpret signs and gestures as calls for war lingered.

Cartier and the Native peoples had other encounters that were far more friendly and welcoming, and included signs that, to date, no others had previously described. As the French explorer made his way to Hochelaga, near modern-day Montréal, the Native peoples serenely welcomed him. Women and girls came towards Cartier “to stroke our faces, arms, and other places upon our bodies that they could touch; weeping with joy to see us; giving us the best welcome that was possible to them and making signs to us…to touch their said children.”[9] The women showed no inhibition in interacting with Cartier and his men. Indeed, they may have viewed Cartier’s entourage as a group of Shamans or healers:

“Cartier and his men were ushered to the centre of the town square and seated on elaborately woven mats. Soon they were joined by the village’s leader, carried in on the shoulders of nine or ten strong men. When he took his seat on a deerskin near Cartier, it became obvious that he was severely paralyzed and that he expected to be ‘cured and healed’ by his visitor. Cartier, taking his cue, ‘set about rubbing his arms and legs with his hands. Thereupon this Agouhanna took the band of cloth he was wearing as a crown and presented it to the Captain [Cartier].’ Then the sick, the lame, the blind, and the aged were brought forward for Cartier to ‘lay his hands upon them, so that one would have thought Christ had come down to earth to heal them.’”[10]

Caressing, touching, hospitality, salutations, gestures, and interpretation–all played a part in this far more friendly, rich, albeit nonverbal encounter between the Hochelaga people and Cartier’s men. But what did these gestures signify? What did it mean to touch and caress? To offer a mat or a band of cloth as a crown? Let’s explore some relevant examples of similar first “words” exchanged among several seventeenth and eighteenth century Mississippi nations to help clarify meaning.

First Signs on the Mississippi

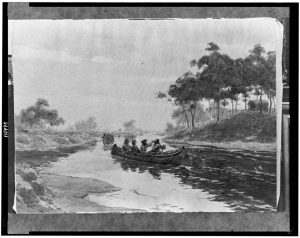

Father Jacques Marquette and his companion Louis Jolliet descended the Mississippi River to the Arkansas River in July 1673. No known Frenchmen had ever interacted with this Native nation, nor did these men know just how to communicate with the Quapaws once they arrived. But Marquette had a bit of a safety net, a calumet given to him by the Illinois to serve as a “safeguard for their passage through the hostile nations farther down the river.”[11] Though he may have primarily viewed the calumet as a simple, albeit colorfully decorated pipe, he soon discovered its ability to “speak peace,” for after leaving the Illinois nation, he and his companions encountered the hostile Metchagamias along the St. Francis River to the west of the Mississippi.[12] As the Frenchmen approached, a Metchagamia threw a war club over their heads. By displaying the Illinois calumet, the Frenchmen went unharmed. Marquette believed this softened the Metchagamias aggressiveness towards them:

“God suddenly touched the hearts of the old men, who were standing at the water’s edge. This no doubt happened through the sight of our Calumet, which they had not clearly distinguished from afar; but as I did not cease displaying it, they were influenced by it, and checked the ardor of their Young men. Two of these elders even,–after casting into our canoe, as if at our feet, their bows and quivers, to reassure us,–entered the canoe, and made us approach the shore, whereon we landed, not without fear on our part. At first, we had to speak by signs, because none of them understood the six languages which I spoke. At last, we found an old man who could speak a little Illinois.”[13]

A few days later, Marquette and Jolliet met the Quapaw nation for the first time along the Arkansas River. As several Quapaws came towards them in two canoes, the leader of the first canoe stood up, held forth the calumet and “made various signs, according to the custom of the country.” Once he reached the Frenchmen, he sang “very agreeably, and gave us tobacco to smoke,” along with sagamité and bread made of Indian corn to eat. Soon after, the Quapaws moved toward the village with one of them “making us a sign to follow him slowly.”[14]

Hawé, ta-taⁿ zha-zhe a-tiⁿ? Bonjour, je m’appelle Jacques.[15] These Quapaw and French words may have been spoken during that first encounter, but full comprehension otherwise failed. Marquette tried to speak their language, but found it “exceedingly difficult, and I could succeed in pronouncing only a few words notwithstanding all my efforts.”[16] Undoubtedly, the Quapaws had trouble pronouncing Marquette’s language as well. Consequently, “speaking” relied heavily on nonverbal communication–sign and body language, languages of ceremony, ritual and reciprocity, gestures of hospitality and honesty. Language was irrefutably “spoken” through nonverbal iterations that initially impacted encounters, interactions and alliances between this and other Native nations and the French in the seventeenth and eighteenth century Mississippi River Valley.

March 1682, René-Robert Sieur de LaSalle, Henri de Tonti, the Recollet Father Zénobe Membré and their men arrived near a Quapaw village sometime around 10 a.m. Sasacoüest (war cries), as described by Father Membré, could be heard coming from the village which was “disturbed by such an unanticipated visit.”[17] Fellow explorer Nicolas de la Salle was certain that “the Arkansas believed that it was their enemies” who were near since they “sent away their women and children.”[18] Alarmed by this rapid, nonverbal response, the Frenchmen quickly paddled to the other side of the river and built a protective fortress. Though this may have conveyed aggression to the Quapaws, no attack took place. Instead, Henri de Tonti “walked out to a point, and the fog lifting, I discovered the village and asked who they were. But because the river was so large, they could not hear me. They pushed from shore in a pirogue and when within voice distance, I asked them, in Illinois, who they were. An Illinois among them cried out Akansa, and he asked me who I was. I responded to him Miskigouchia which is the name that the southern Native peoples give us.” Someone among the French party further cried out Nicana, the Illinois word for friend.[19] Unsatisfied by their responses, a Quapaw shot an arrow towards Henri de Tonti and his companions. “If one had shot back, this would have been a sign that one demanded war, but seeing that we did not shoot back, they went to their village to announce that we were peaceful.” Not long after, “Kapaha, chief of the burg…along with six of his principal people” came on shore with the calumet. The Quapaws “entered our fortress and presented the calumet to M. de la Salle and all the others to smoke, also making the sign that one go to their village.” La Salle and his companions accepted the invitation and “were received with all possible demonstrations of joy and affection.”[20]

Some fifteen years later and just a couple of days after Christmas 1698, Fathers Jean-François Buisson de Saint-Cosme, Antoine Davion, and François de Montigny, missionaries from the Séminaire de Québec, also visited a Quapaw village: “Seeing several wooden canoes along the riverbank, and a Quapaw standing next to them, one of the Frenchmen quickly grabbed a calumet and began to sing out of fear he [the Quapaw] would flee once he saw us. Hearing his loud voice in the nearby village, some fled, while several Quapaws came to the water’s edge, calumet in hand. They approached us and rubbed our bodies and then themselves, a mark of esteem among their culture. They then lifted us onto their shoulders and carried us to the Chief’s cabin.” Saint Cosme feared “that the one carrying me would fall due to the muddy bank. I jumped off of his back and walked up the hill. But once at the summit, the Quapaw insisted I continue my hospitable ride to the cabin.”[21]

In a matter of days, these Frenchmen made their way to Tourima, a second Quapaw village at the mouth of the White River. As they neared the village, “six Indians met us with the calumet. They led us to the village where we experienced the same ceremonies as we had during the last two days at the other village.”[22] And just a couple of months later, Pierre le Moyne, Sieur d’Iberville made his way into the lower Mississippi River Valley via the Gulf of Mexico. He too had his own nonverbal encounters with the local communities. One Native group went so far as to “pass their hands over their faces and breasts, and then pass their hands over yours, after which they raise them toward the sky, rubbing them together again and embracing again.”[23]

Each of these encounters began with some form of recognition that a stranger was present. Strategies of signaling, bodily responses and the like communicated hopefulness and concern. More formally, the presentation of the calumet–a powerful symbol that spoke peace–eased these fearful encounters and defined one’s status as ally or enemy simply by displaying it to the stranger. Rather quickly, the French came to view the calumet as “a useful element of frontier diplomacy, based on principles of political and economic interaction held by Europeans during the colonial era.” When nonverbally presented to the other, one established alliance and friendship, secured safe passage within the region, as well as trade relations and alliance between the different cultures.[24]

But shooting a canon or fire-lance enunciated a warning–back off! The Native peoples’ flight away from Cartier provided the answer–we run from you; we are frightened. A Quapaw shooting the quieter arrow towards de Tonti asked a question–Do you come in war or peace? Silence uttered the response–We come in peace. Similarly, when the Metchagamias threw a club over the heads of Marquette and Jolliet, this too asked of their purposes. Rather than returning violence, Marquette lifted up the calumet to speak peace and all hostilities ended. The Metchagamia terminated the strife-filled conversation in their own peaceful manner by throwing bows and arrows into the canoe. Even gun shots served as nonverbal communication among some Native groups. Marquette remarked how the Illinois “use guns…especially to inspire, through their noise and smoke, terror in their Enemies.”[25] Henri Joutel, a survivor of LaSalle’s failed Texas colony, further noticed that both the Quapaws and the Illinois used gunshots as a nonverbal salutation of welcome and farewell. When Joutel first encountered the Quapaws in 1687, he stood and observed their village for a time from the opposite bank. Eventually, “we saw two men dressed [in the French style] come out of the house. They each shot their guns as if to salute us, and a Quapaw shot one off within the village as well. The latter, who must be the Chief, actually shot first. We responded to their shots with several of our own, which greatly pleased the Indians who accompanied us [from the Caddo region].”[26]

Both the Illinois and the Quapaws had adopted this European form of communication to welcome and bid farewell to individuals. Joutel and his men “were saluted at our departure just as we had been upon arrival” within every Quapaw village they visited.[27] Even while traveling with the Quapaws to the Illinois territory, Joutel and the Quapaws “caught site of some [Illinois] Indians on the banks of the river. Having spotted us, they sent one of their group on foot towards us to see who we were. We readied our guns and made a sign to the Quapaws to advance. As the Indian approached, he silently began to look at us more closely. We made him understand that we had come with La Salle, and after he had looked at us for a time, he made a sign to us to advance towards his people who were further up.” As they drew nearer to each other, the Illinois “shot off several gunshots to salute us. Three of us returned the salute–le Jeune Sieur Cavelier, Tessié and myself [Joutel].”[28]

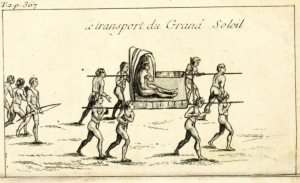

Aside from borrowed, salutatory gunshots, other nonverbal signs expressed important cultural points within a Native community. Among the Quapaws, one often described the approach of six men in a canoe, likely representative of the balanced nature of Quapaw society–Sky People and Earth People, the sky realm, earth realm and water realm. Physical contact projected feelings of esteem among the Native peoples and towards others–“Allow us to caress you and then ourselves so that your spirit can become one with ours.” The caresses Cartier received were clearly an expression of esteem by the Hochelega who longed, through touch, to enmesh his spirit with theirs to strengthen themselves spiritually and perhaps even to help them overcome their illnesses and disabilities. But carriage also communicated esteem. Cartier saw the Chief of Hochelega borne on a platform into the midst of their first encounter. The Natchez and Taensas did much the same with their own Chiefs. The Quapaws and the Caddos even carried Frenchmen on their backs and shoulders into their respective villages, communicating the esteem they had for guests in their environs. Such esteem likely signified Native peoples’ belief of Frenchmen as “spirits” because of the advanced technologies they carried with them, that “French technology was beyond the power of ordinary human beings…the French themselves had nonhuman power.”[29] This led some to refer to the French as “manitous,” or “strange and powerful men whose real significance was not yet apparent.”[30] Guns, in fact, led some to believe that the French could control the weather–thunder and lightening. For this and other reasons, some burial sites such as the Tunica Treasure in Louisiana contain hundreds of French-made objects suggesting that when one died, “on that journey they needed the same things that they had used [or found power within] in life: blankets, kettles, guns, knives and beads” or even mirrors, pitchers and the like.[31]

In initial encounters, rich, nonverbal communication spoke words of introduction, welcome, a keen craving to experience the other’s spiritual strength, and the pursuit of peace, all without words. But even once initial greetings had ended, communication was far from over. The Quapaws, for example, used signs to invite their guests to their village, to take a seat and/or rest “under the scaffolding of the chief of the warriors…clean, and carpeted with fine rush mats,” or with various skins or furs.[32] Such hospitable communication continued through the offering of various plates of food–sagamité, whole corn, venison, fish. Indeed, Marquette was quite moved by how the Quapaws were “very obliging and liberal with what they have,” especially since they otherwise lacked food–“they dare not go and hunt wild cattle, on account of Their Enemies.” Yet even with the shortage of food in their village, “feasts are given without any ceremony. They offer the Guests large dishes, from which all eat at discretion and offer what is left to one another.”[33]

Recollet Father Membré further commented on Quapaw nonverbal kindness and hospitality: “Seeing that we were not wanting to lodge separately in their cabins, they let us to freely do as we wished, sweeping the place where we wished to lodge, bringing in posts for cabins, providing firewood for the three days we stayed among them, treating us to banquets, one after the other.”[34] Five years later, Joutel experienced this same Quapaw generosity. He feasted in every village he entered, so much so that “we would have had, in truth, need for several stomachs since they were sometimes four or five waiting on us to take us each to their cabin. But even though we did not need [all this food], we continued to go so as to not dismiss them and indeed to please them,” or “more so to satisfy them than to eat.”[35] Even when Joutel and his men arrived well after midnight at the Kappa village of the Quapaws, this due to heavy rains along the river, “since we were wet, one made a fire to dry us, and we were lightened by some young people who held torches made out of dried cane that served as candles.” In every village Joutel entered, “We were taken to the Chief’s cabin where we saw things arranged in the same way as before, that is, skins spread out on which we were asked to sit and they brought us food to eat.”[36]

With peaceful actions and reactions, one more easily entered into a village. Nonetheless, Frenchmen were often “brought up short by their urgent need but excruciating inability to speak with their hosts–to make their purposes and wants known, to convey what they had to offer in return for continued cooperation, and to establish their character as men whose word could be trusted.”[37] Yet even without knowing the other’s language, the Quapaws still nonverbally communicated graciousness and generosity to their French guests who responded in kind by accepting Quapaw kindness. The Quapaws even communicated honesty and respect to the French, through embodied actions. Membré found the Quapaws “joyful, honest, generous. The youth, the most agile we had seen, are otherwise so modest and so reserved that not one broke from this to enter our cabin, always standing quietly at the door…we lost not a pin among them.”[38] Joutel described how “a large number of [Quapaws] came to our landing, some of whom took us to the Chief’s cabin, and the others carried our supplies. This is their custom, in effect, to empty the canoes when strangers arrive among them, and I admired the loyalty of these people…I did not see them steal anything that we had.”[39] Though he initially “did not trust this,” Joutel soon realized that “the people of this nation were not thieves like all of those towards Canada, a comment I have since come to appreciate as true.”[40] Years later, Father Saint-Cosme and his missionary companions experienced this same honesty and respect: “They carried everything we had into a cabin where it remained for two days without anything taken or lost,” he wrote. Even when one left a knife in a cabin, “a Quapaw at once brought it.”[41]

Aside from expressing generosity and honesty through bodily actions, Native peoples also communicated joy and thanksgiving: Women “came freely to us and stroked our arms with their hands, and then raised their joined hands to the sky, making many signs of joy,” wrote Cartier.[42] Even when receiving trifles, they expressed this same gratitude: “We gave them knives, paternosters of glass [rosaries], combs, and other articles of little worth, for which they made many signs of joy, raising their hands to the sky while singing and dancing in their boats.”[43] Select Mississippi-based scenarios were similarly joyful and appreciative. Among the Taensas peoples who once lived in what is today Northeast Louisiana, whenever they received gifts, they accepted them and then “reverently carried them to their temple.” The Seminary priest Francois de Montigny remarked how the Taensas “raised their hands to the sky, then placed them on their heads as they turned to the four directions.” This was “all in thanks to the spirits for these offerings. After the ceremony of Thanksgiving, gifts were shared with the villagers.”[44]

Of course joy is a universal emotion that was quite easy to identify. But a contrasting emotion, fear, also emerged beyond those scenarios mentioned earlier. Cartier for example, took two young men to France presumably to learn French. When returned to their village of Stadaconna, the people received Taignoagny and Dom Agaya with joy. But immediately, the two men’s fondness for Cartier seemed severely diminished as they stood at a distance from the French entourage. The two men were “wholly changed of purpose and resolution, and would not enter into our said ships…[thus] we had some distrust of them.”[45] Along the Mississippi, as four Quapaws escorted Joutel and his Frenchmen to the Illinois country in 1687, body language and physical actions signaled fear along their journey as well. We “camped on a small island to be more secure because the Quapaws were concerned about an enemy nation that they called Machégamea who they said were often on the river’s edge. This is why we always camped on whatever island or some point of open land so as to better see around us and keep good watch, which reassured the Quapaws and alleviated the fear of being surprised while providing them with a manner to save themselves.” Though burgeoning allies, the Frenchmen also noticed “a change in the Quapaws, in their humor and mannerism” as the journey continued. “This gave us some fear.” Indeed, the Frenchmen “were particularly alarmed when the hermaphrodite [Two Spirit] told us that they had intentions of leaving us, something which obligated us to take hold of our arms and increase our guard during the night, out of fear that they would abandon us.” Alarmed, Sieur de Cavelier, the Sulpician priest, nonverbally signaled his own wariness of the Quapaw guides when he “remained in the canoe, for solace, or to prevent any temptation that the Quapaws might take to leave us, or out of sheer terror, or another reason.”[46] Despite the Frenchmen’s anxieties, the Quapaws gave them no harm, nor did they abandon them along their journey.

Most remarkable was Cartier’s attempt to hide his own fears by nonverbally signaling strength during a harsh Québec winter in which his men suffered terribly from scurvy. Great trepidation had grown in the minds of the Frenchmen. They were certain that the region’s Native people were plotting against them, particularly the two young men whom they had taken to France who, upon return to Stadaconna, remained strangely distanced from them. But many of the Frenchmen were sick and dying from scurvy within their abode. To ward off any potential attack from the Native people, “when they [the Stadaconna] came near our fort, our captain, whom God has always preserved, would come forth straight before them with two or three men, both sound and sick, whom he had come out after him…the said captain made the said [remaining] sick men beat and make a noise within the ships with sticks and stones, feigning to calk [the ship],” to make it sound as if they were alive and healthy.[47]

Cartier’s men were suffering and desperately needed help. But observing the Native peoples’ own body language and carriage, Cartier noticed that though they had previously been ill, they now seemed “sound and well,” upright and strong. Consequently, Cartier subtly asked Dom Agaya who could speak some French for his advice:

“Hoping to know from him how he [Dom Agaya] was cured, so as to give aid and succor to his men…the captain asked him how he was cured of his sickness to which Dom Agaya responded that he was cured by the juice and refuse of the leaves of a tree, and that it was the only remedy for the sickness. The said captain asked him if there was not some of it thereabouts, and if he would show him some of it in order to cure his servant, who had taken the said sickness…not wanting to declare to him the number of the crew who were sick. Then the said Dom Agaya sent two women with the captain to fetch some of it, who brought nine or ten branches of it, and showed us how one should strip the bark and the leaves from the said tree and put the whole to boil in water, then to drink of it every other day and put the refuse on the swollen and diseased legs, and that the said tree would cure all the sick. They called the tree in their said tongue amedda.”[48]

Ultimately, fear was overcome through signs, some verbal language, trust and a cure. Within a few days, all of Cartier’s remaining men began to recover from the dreaded disease.

Though rarely mentioned, facial expressions also communicated thoughts and feelings. Two French Huguenots–Jean Ribault and René Laudonnière–explored the future Florida and South Carolina regions in the mid-sixteenth century so as to establish a French colony. One day, they noticed that “the chief had a target erected to test our guns against his arrows. But that did not work out well for him because as soon as he knew that our guns could pierce easily what his arrows could not even scratch, it vexed him greatly to understand how that could be so. In the meantime, wishing to conceal in his thoughts what his face openly disclosed, he changed the subject and begged us to spend the night at his house…that he wanted to repay us with a thousand presents.”[49] Similarly in 1699, the Houmas, who resided in the southern Mississippi River Valley, received various gifts including a 14 pound cannonball from Sieur d’Iberville as he passed through their village. As observed by Father François de Montigny a few weeks later, “they clearly understood that it had a different effect from their arrows.”[50]

One even communicated age through signs as seen in this additional non-verbal exchange from sixteenth century Florida:

“The chief took them [Ribault and Laudonnière] to the lodgings of his father, one of the oldest persons on earth….they interrogated him about his age, and he answered that he was the oldest in a line of five generations, and he showed them another old man who sat across from him and who far exceeded him in age. This was his father and he resembled a dead carcass more than a living man. His sinews, veins, arteries, bones, and other parts appeared through his skin in such a way that they all stood out from each other. He was so old that he had lost his sight and could speak only one word at a time and even that with exceeding difficulty. M. d’Ottigni…spoke to the younger of the two old men and asked him further about his age. Then the old man called in a group of Indians and, striking twice upon his thigh and laying his hand upon two of them, he showed him by signs that these two were his sons. Then striking their thighs, he showed him others not so old who were the children of the first two, which procedure continued in the same manner until the fifth generation. Yet this old man had a father still alive, older of course than himself.”[51]

Greetings, hospitality, nonverbal questions and answers as well as other visualized feelings and statements relayed important information in any encounter. As one settled in, reciprocity and the exchange of gifts enunciated strong words of alliance, balance and faith. Indeed, gifts were “the word.” Joutel understood this as he sought to secure Quapaw guides for his journey north to the Illinois country. As he made his way to each of the four Quapaw villages, he requested help from each leader and offered thanks for their assistance through gifts for each village: “a gun, 100 powder charges, as many balls, two hatchets and six knives, some beads and rings.” To further communicate good will, “and to better encourage them,” Joutel offered to leave a Frenchman in place of the provided Quapaw guide so as “to show them that we wanted to return. They were content with this.” Even as they left for the Illinois territory, they offered their horses from which the Quapaws might profit, showing them “that we leave them our best things.”[52]

Joutel understood the importance of communicating good will to the Quapaws. He expressed this through complimentary, reciprocal gestures that spoke words of thanks for what was given to him. But Joutel furthered his promise to the four guides provided by each village as well. “We took care to compensate the Quapaws who had guided us to the fort [among the Illinois]. We had promised each a gun, two hatchets, some knives, powder and balls and other trifles. We gave these to them. One of them, truly ill after having eaten the raw fat [of a buffalo], died the second day of our arrival.” Through an Illinois interpreter, “We expressed our sadness to them for his death…we gave to these companions of the dead man the promised gun and other things that were to be given to him so that they could give them to the village he was from or to his parents….We told them of the esteem we had for them, of which they seemed content. There was nothing on our part that troubled them.”[53]

But sometimes Frenchmen were slow to grasp the power of words spoken through gifts. For example, during the mid-eighteenth century, the French struggled to keep the peace with the Chickasaws who lived in the region of modern-day Mississippi and Alabama. Consequently, to protect themselves, they hoped to maintain a strong reliance with the Choctaws, enemies of the Chickasaws, who resided in southern Mississippi and Alabama, near the French fort at Mobile. But presents due this nation in November 1732 were not given since there were simply “none to give.” War, lack of transport into the region, meager funds–all greatly limited French access to sufficient quantities of trade goods. Anger arose and attraction to the Carolina English and their English “stuff” ensued. Consequently, to alleviate Choctaw resentment, French officials gave them as much powder and balls as they could. Though the delay in regular gifts continued, the Choctaws “expected double presents the next spring.”[54] Presents spoke power and the longer they were delayed or declined in quality, the more dangerous it became for the French. Longing for goods, a Choctaw chief, otherwise allied with the French, “was met by English traders [allies of the Chickasaws] laden with goods.” Enticed by their words, he “agreed to take English presents to his people and speak to them on behalf of entering into trade with the English.” On returning home, the chief provided a tantalizing overview of the English traders’ vast variety of trade goods that was in sharp contrast to what they were receiving from the French. Indeed, the Choctaws were so frustrated with the French that “the majority of the nation decided to lay down their arms and fight the Chickasaws no longer.”[55] Consequently, to hold on to the fragile French alliance with the Choctaws, Bienville “distributed many presents among the faithful chiefs in the hope that they might regain some of their authority.” As for those who were less faithful, Bienville withheld their presents to send a clear message–“those who supported France were the only ones that would receive presents.” He took a risk and succeeded. Nonetheless, “if things had not gone so well…he would have had no choice but to promise double presents for the next year.”[56] We will further explore the topic of objects and communication in the next chapter.

Despite the many seemingly successful nonverbal encounters, signing had its challenges. The Jesuit Father Pierre Biard wrote of how one had to “make a thousand gesticulations and signs to express to [the Indians] our ideas, and thus to draw from them the names of some of the things which cannot be pointed out to them. For example, to think, to forget, to remember, to doubt; to know these four words, you will be obligated to amuse our gentlemen for a whole afternoon at least by playing the clown; and then, after all that, you will find yourself deceived, and mocked anew.”[57] Indeed, Iberville understood all too well the signs given him by the Bayogoulas near the mouth of the Mississippi River and chose to conceal what he understood from his own men: “When the French bateaux pulled up at a friendly Bayougoula village for the night, the chief asked if the strangers would like a warm woman for every man in the company. Apparently, Iberville was alarmed by this traditional token of native hospitality and ‘by showing his hand to them…made them understand that their skin–red and tanned–should not come close to that of the French, which was white.’” As Gray and Fiering remarked, “The grumbling of the men was not recorded for posterity but is plainly audible even at this remove.”[58]

But signing could also be detrimental to an individual particularly if incorrectly done. As the French and English engaged in war throughout the northeast, the Mi’kmaqs, long-time French allies, were taught to show themselves as the praying ones, “les Priants,” and to identify any non-Catholic infiltrators into their region, i.e. the English. Consequently, when one Englishman was imprisoned, suspicions arose when he made the sign of the cross repeatedly and incorrectly, “unfortunately using his left hand.” One among the Mi’kmaqs noticed this and said “make him do [the sign] a second time…the Englishman made the sign of the cross again with the left, believing he had done it correctly did it a dozen more times.” Shortly after, he was executed.[59]

Even how one dressed served as a form of visual, nonverbal communication, “creating, affirming, and upholding identity on a daily basis.”[60] Priests, of course, wore black cassocks that “covered their entire body and rendered it neutral, absent of any hint of masculinity or sexuality.” The color black was no accident. It “signified mourning and poverty—the dying of self to serve God in all ways; the letting go of all things to focus solely on God.”[61] The color black, however, proved frightening for some Native peoples. Father Antoine Davion managed to baptize one child among the Houmas near modern day Angola, Louisiana in 1699, but “could not baptize the second as the mother was not accustomed to seeing cloths so long and so black.” As Davion approached from one side, “she fled to the other.” Frère Alexandre, a hospitalier from Montreal, who was “graced with good conduct and charity for the ill,” baptized the child without difficulty. “The mother had no fear of him,” for he was not clothed in black.[62] But so concerned were priests with regard their identity, that the early eighteenth century Tamarois missionary, Father Marc Bergier poignantly remarked: “I’m just as naked as [Fathers] Saint-Cosme and Boutteville; I am wearing my cassock from France in tatters, resewn with scraps tossed out by others.” While Bergier “did not wish to complain…as this does not please God,” a good cassock was a small need that had to be met “to prevent unwanted whispers” regarding “his natural state, and the aftermath that could result.” Simply put, “if I don’t receive some clothes [white collars and a cassock]…I will have to dress in skins.” Bergier had to vest as a priest, to communicate to others that he was a man of God, to communicate his position as a Seminary missionary, not as a Jesuit nor a Native convert.[63]

At times, one literally “cross-dressed” to express alliance. The Tunicas, for example, were “the ones that count the most” since, according to the French, they were “the only tribe the French could consistently count on for military aid.”[64] Indeed, the Tunicas regularly received annual gifts from the French above any trade goods provided. Further, Chief Cahura-Joligo regularly embraced the French mode of dress.[65] He was “not at all troubled by this style of clothing…for it had been a long time since he dressed as an Indian.” He was “perfectly comfortable” with his “status and practices” as a Tunica but, regularly interacting with Frenchmen in his midst, “had to arrive at some common conception of suitable ways of acting.”[66]

But dress further identified individuals whose spirit or vision quest directed them towards the role of the Two-Spirit, a male individual “who from a young age dresses as a woman.”[67] Fathers Marquette and Saint-Cosme both met a Two Spirit among the Illinois and the Quapaws respectively. Neither understood the significance of this individual and his importance for balance and integrity of a village, but a Two Spirit had a significant role to play. These men could go to war but could only use clubs, not bows and arrows. The Two Spirit also participated prominently in ceremonies and dances, including the calumet ceremony whereby they could “sing, but must not dance,” wrote Father Marquette. Whether they were a Quapaw or an Illinois Two Spirit, their community held them in high esteem. As Marquette witnessed: “They are summoned to the councils, and nothing can be decided without their advice.” These individuals were considered manitous, “spirits, or persons of consequence.”[68]

Conclusion

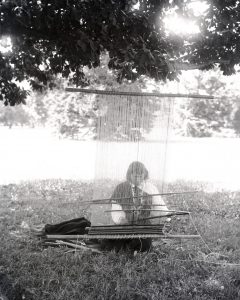

Sign language, bodily expressions, gestures, clothing, calumets and gifts regularly served as nonverbal modes of communication throughout the colonial period. Needless to say, context was important to help decipher and/or express what one desired through such communication. As time wore on, such visually-based language lingered. Even as new peoples entered the region, and new languages challenged one’s ability to verbally communicate, nonverbal communication mattered. Indeed, after the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, English speakers flooded the Mississippi valley with their new technologies and vocabulary in tow. In the case of the English botanist Thomas Nuttall, he wrote of a simple encounter he had with some Quapaws near Arkansas Post. “This evening we were visited by three young men, a boy, and a [Native woman] of the Osarks [sic], a band of the Quapaws or Arkansa Indians….They informed me, partly by signs, that their company was about five or six families or fires, as they intimated, out on a hunting excursion.”[69] And as Americans forced Native peoples into Indian territory, reliance on Plains Indian signing books increased so that those who entered the region might have some knowledge of how to communicate with the Native communities therein. Even in the early twentieth century, signs were still used as seen in this video example of nonverbal interaction between several Native peoples and an army officer. No matter what nonverbal gestures or signs one encountered, such early interaction set the stage for future communication between Native peoples, Europeans and Americans across North America. All along the Mississippi and into the Pays d’en haut, nonverbal communication was widespread, intricate, yet vital to the welfare of all concerned.

Questions and Activities:

Answer the following questions:

- Indicating “time” through gestures, Marquette told the Illinois that he promised “to pass again by his village, within four moons.”[70] He learned this nonverbal strategy from other Native peoples. What sign might Marquette have used in order to indicate this passing of time?

- When Cartier visited the St. Lawrence River Valley in the 1530s, a map was produced with numerous images that expressed various modes of communication. Closely examine this map and identify sources of nonverbal communication you see present within. Can you spot Cartier? What is he doing? How are others treated? Why?

- Examine this text entitled “Universal Indian Sign Language” Can you understand the signs? For what purpose was it made and who had input? What can you sign from this particular text? Create a brief story that you sign utilizing the suggested gestures present.

- Closely analyze the following text and answer these questions: What signs, gestures, and body language played a part in this exchange? What did they “say” and what was the outcome? Why?

“The next day we arrived around noon among the Tamarois. They had received early warning of our arrival from some of the Cahokias who carried this news to them. A year earlier, they had some strife with de Tonti’s men. Thus, they were afraid and all the children and women fled from the village. The chief and several of his men came to receive us at the water’s edge and to invite us to their village. We did not go since we wanted to prepare ourselves for the Feast of the Conception. Thus, we set up camp on the other side of the river. Monsieur de Tonti went to their village, and after giving them some reassurance, brought the chief to us who asked us to come to his village. We promised him that we would. The next day, after having said mass, we went with de Tonti and seven well armed men to the village. They came to meet us and led us to the chief’s abode. All of the women and children were there. No sooner had we entered the chief’s house than the young men and women broke in a segment of the home to see us. They had never seen black robes except for those who remembered seeing the Jesuit Father Gravier who traveled to their village. They gave us food to eat. We gave them a little present… We told them this was to show them that we had a good heart and that we wanted an alliance with them….The Tamarois were living on an island lower down from their village perhaps to have easier access to wood…but also out of fear of their enemies.”[71]

- Céline Carayon, Eloquence Embodied: Nonverbal Communication Among French and Indigenous Peoples in the Americas (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press and Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2019), 41. ↵

- Carayon, Eloquence Embodied, 49. ↵

- William Dunbar and Thomas Jefferson, "On the Language of Signs among Certain North American Indians," American Philosophical Society, Transactions, VI (1809): 2. ↵

- Portrait of Tendoi - Photo Lot 24 SPC Basin Shoshoni BAE 1-42 00866700, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution ↵

- James P. Baxter, A Memoir of Jacques Cartier, Sieur de Limoilou (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1906), 100. ↵

- Baxter, Memoir, 103-04. Baxter suggests that this phrase may translate as "We wish to have your friendship." ↵

- Ramsay Cook, The Voyages of Jacques Cartier (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 20-21. ↵

- Cook, Jacques Cartier, 21. ↵

- Baxter, Memoir, 167. ↵

- Cook, Jacques Cartier, xxxiii. ↵

- A calumet was a sacred, long-stemmed pipe that many nations including the Illinois and the Quapaws used to project desires for friendship and alliance to guests within their villages; Thwaites, "Preface" & "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 15. ↵

- Michel McCafferty suggests that this spelling of Metchagamias “should now be the accepted literacy or historiographic form of this name” based on linguistic analysis. Michael McCafferty, “While Cleaning Up a True Name,” Le Journal 39, no. 3 (June 2023): 13. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 151-153. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 153. ↵

- These texts mean “Hello, what is your name” in Quapaw, according to the Quapaw Tribal Ancestry: http://www.quapawtribalancestry.com/quapawdictionary/n.htm and “Hello, my name is Jacques” in French. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 157. ↵

- Pierre Margry, "Lettre du Père Zénobe Membré," Découvertes et Etablissements des Français dans l’Ouest et le Sud de l’Amérique Septentrionale (1614–1754), Lettres de Cavelier de La Salle et correspondance relative à ses entreprises (1678–1685), vol. 2 (Paris: Imprimerie de Jouaust, 1877), 207; John Gilmary Shea, "Narrative of Father Membré," Discovery and Exploration of the Mississippi Valley (Alban: Joseph McDonough, 1903), 172. ↵

- Pierre Margry, "Récit de Nicolas de la Salle," Découvertes et Etablissements des Français dans l’Ouest et le Sud de l’Amérique Septentrionale (1614–1754), Mémoires et Documents Originaux, vol. 1, 1614–1684 (Paris: Maison Neuve, 1879), 553. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Henri de Tonty," Découvertes, vol. 1, 598-99; De Tonti’s writing of Miskigouchia is very close to the Miaimi/Illinois spelling of meehtikooši- (n.an) French; meehtikoošia | French person; meehtikoošiaki | French people; niihkaana | My friend - stems from the Miami/Illinois language, https://mc.miamioh.edu/ilda-myaamia/dictionary ↵

- Margry, "Récit de Nicolas de la Salle," Découvertes, vol.1, 553; Margry, "Les Akansas se Soummettent à la France," Découvertes, vol. 2, 182. ↵

- Likely, they stepped into an Antichon, a shelter open on four sides. “Father Jean-François Buisson de Saint-Cosme to Mgr de Laval," January 2, 1699, Archives du Séminaire de Québec [hereinafter ASQ], Lettres R, no. 26, p. 15; Linda Carol Jones, The Shattered Cross, French Catholic Missionaries on the Mississippi River, 1698-1725 (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2020), 75; Thwaites, "Lettre du Père du Poisson, 3 Octobre, 1727," JRAD, vol. 67 (Cleveland: Burrows Brothers, 1900), 321. ↵

- “François de Montigny to Monsieur...,” May 6, 1699, Archives Nationales de France [hereinafter ANF], Série no. 3JJ, vol. 387, C3-52; “Saint-Cosme,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 26, p. 18; “François de Montigny to Ma Revérende Mère,” January 2, 1699, ANF, Série K 1374, no. 84, p. 1. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 20. ↵

- George Sabo, III, "Rituals of Encounter: Interpreting Native American Views of European Explorers," in Cultural Encounters in the Early South, Indians and Europeans in Arkansas, ed. Jeannie Whayne (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995), 78-79. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 127. ↵

- Pierre Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes et Etablissements des Français dans l’Ouest et le Sud de l’Amérique Septentrionale (1614–1754), Mémoires et Documents Originaux, vol. 3, 1669–1698 (Paris: Imprimerie de Jouaust, 1878), 436-37. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 451-452. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 475. The Jeune Cavelier listed was not the brother of LaSalle. However, Jean Cavelier, a priest, was the famed explorer's brother. ↵

- Bruce M. White, "Encounters with Spirits: Ojibwa and Dakota Theories about the French and their Merchandise," Ethnohistory 42, no. 3 (1994): 369. ↵

- White, Middle Ground, 25. ↵

- White, "Encounters," 377; the items pictured just below are from the 18th century French. The bottle which says "à Louis" is homage to the King. The plate displays a verse from a French drinking song: "Pour friend Gregory a little of this charming juice. I feel my soul warm at each moment." ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 153-155; Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 440. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 157. ↵

- Margry, "Lettre du Père Zénobe Membré," Découvertes, vol. 2, 208. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 452-53, 455. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 457-59. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 21. ↵

- Margry, "Lettre du Père Zénobe Membré," Découvertes, vol. 2, 208. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 459. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol 3, 438. ↵

- “Saint-Cosme,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 26, 16-17. ↵

- Baxter, Memoir, 106. ↵

- Baxter, Memoir, 109. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 83; “Pièces Justicatives,” Archives du Séminaire des Missions Etrangères de Paris [hereinafter SMEP], vol. 345, Pièce E, p. 911; “de Montigny,” ANF, Série K 1374, no. 84, p. 1; “Lettre de Thaumur de la Source a Ma Révérende Mère,” April 19, 1699, ANF, Série K 1374, no. 85, pp. 2–3; “François de Montigny to Saint-Vallier,” August 25, 1699, ASQ, Missions, no. 41, p 15. ↵

- Baxter, Memoir, 148. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 465, 469-71. ↵

- Baxter, Memoir, 193. ↵

- Baxter, Memoir, 195. ↵

- René Laudonnière, Three Voyages, Translated with an Introduction and notes by Charles E. Bennett (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2001), 67-68. ↵

- “de Montigny,” ASQ, Missions, no. 41, pp. 5–7. ↵

- Laudonnière, Three Voyages, 64-65. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 447, 451, & 455. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 483. ↵

- Michael J. Foret, “War or Peace? Louisiana, the Choctaws, and the Chickasaws, 1733-1735,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 31, no. 3 (1990): 276-77; "Cremont to Maurepas," May 15, 1733. Archives Nationales d'Outre Mer [hereinafter ANOM], Archives Coloniales [hereinafter AC], C 13a, 17:266-267v; "Bienville to Maurepas," July 26, 1733, ANOM, AC, C 13a, 16:282v. ↵

- Foret, “War or Peace,” 279; "Bienville to Maurepas," March 15, 1734, ANOM, AC, C 13a, 18:130. ↵

- Foret, “War or Peace,” 280; "Bienville to Maurepas," March 15, 1734, ANOM, AC, C 13a, 18:130-135. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 4; Thwaites, "Lettre from Father Pierre Biard to the Reverend Father Provincial, at Paris," JRAD, vol. 2 (Cleveland: Burrows, 1896), 11. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 26; Pierre le Moyne d’Iberville, Iberville’s Gulf Journals, ed. and trans. Richebourg Gaillard McWilliams (Tuscaloosa: Univ. of Alabama Press, 1981), 24. ↵

- Pierre Antoine-Simon Maillard, “Lettre de M. L’Abbé Maillard sur les Missions de l’Acadie et particulièrement sur les Missions Micmacques,” in Les Soirées Canadiennes, vol. 3 (Québec: Brousseau Frères, 1861), 317-20. ↵

- Sophie White, “Massarce, Mardi Gras, and Torture in Early New Orleans,” William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 3 (July 2013): 499. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 163. ↵

- “de Montigny,” ASQ, Missions no. 41, pp. 11-12. ↵

- “Marc Bergier to Louis Ango de Maizerets,” March 19, 1702, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 51, p. 2; “Marc Bergier, Missionnaire aux Tamarois,” June 14, 1700, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 44, p. 4; “Marc Bergier to unknown,” July 14, 1704, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 67, p. 2; “Marc Bergier to unknown,” June 10, 1702, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 54, pp. 3–4; Jones, Shattered Cross, 135. ↵

- Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix, Histoire et description générale de la Nouvelle France: avec le journal historique d’un voyage fait par ordre du Roi dans l’amerique septentrionale, vol. 3 (Paris: Nyon, 1744), 433; Jeffrey P. Brain, The Tunica Treasure (Cambridge, Mass: Peabody Museum, Harvard University Press, 1970), 260. ↵

- While the image to the left is not Cahura Joligo, it does present a Choctaw Chief who wore European fashion to a certain extent. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 213; White, Middle Ground, xxi. ↵

- “Saint-Cosme,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 26, pp. 15–17. Note: Women also took on male identities and thus were referred to as Two Spirits as well. ↵

- Jacques Marquette, “The Mississippi Voyage of Jolliet and Marquette, 1673,” American Journeys Collection, AJ-051, Wisconsin Historical Society Digital Library and Archives, p. 244. ↵

- Thomas Nuttall, A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory during the Year 1819 : with Occasional Observations on the Manners of the Aborigines (Philadelphia: Thomas H. Palmer, 1821), 61-62. ↵

- Thwaites, ""Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 125. ↵

- St. Cosme, ASQ Lettre R, no. 26, p. 13. ↵