1 French, Native Peoples and Communication

How do you communicate with someone who does not speak your language? How does it feel to not understand or to be misunderstood? How do you ask a question or respond to another without the ability to speak their language? As you prepare to read this book on language encounters in the French Colonial era of the Mississippi and beyond, think about these questions for a moment.

Language encounters between the French and Native peoples of North America began when Jacques Cartier reached the St. Lawrence River valley in the 1530s.[1] Communicating primarily by signs, Cartier and various Native individuals participated in seemingly friendly communication as they attempted to “speak” with one another. Almost immediately, Cartier experienced the linguistic diversity of the region’s Indigenous, with Native communities located within just a few miles of each other capable of speaking distinctly different dialects and languages. Undoubtedly it was difficult for either culture to understand the other deeply or even accurately. Almost certainly, any language shared between Cartier and those he encountered included pointing, showing, facial expressions, attempts at pronunciation, curious looks, ephemeral drawings in the dirt–you name it!

Eventually interactions ceased. Cartier’s efforts to establish some semblance of French claim in North America ended after just a few attempts. But other Frenchmen soon followed, though far from the shores of the St. Lawrence River. Huguenots Jean Ribault and René Goulaine de Laudonnière attempted to colonize the region of modern-day Florida and southeastern South Carolina in the 1560s. They too encountered a diversity of languages and cultures. Both they and the Native peoples they encountered had to find ways to communicate verbally and nonverbally. Like Cartier, these Frenchmen also failed to colonize their explored region. Only by the early seventeenth century, when Samuel de Champlain arrived in the St. Lawrence River Valley did French colonization finally take hold. For the next decades and centuries, encounters and communicative feats proved constant between numerous Native nations and the French in what would be termed—New France. As this Québecois region became more stabilized in the eyes of the French, missionaries and explorers such as Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet in 1673, and René-Robert Cavelier Sieur de LaSalle and Henri de Tonti in 1682 pushed farther away from the Québec center than any other Europeans had previously done and reached the Mississippi River Valley. Missionaries soon followed and by the end of the seventeenth century, priests from the Séminaire de Québec–Jean-François Buisson de Saint-Cosme, François de Montigny, Antoine Davion, Marc Bergier and Nicolas Foucault–variously served among Tamarois, Natchez, Taensas, Tunicas and Quapaws. French Jesuits served within the Pays d’en Haut (the Great Lakes Region), among the Illinois and within the Mississippi River Valley.

Native peoples from the central North American continent, particularly from the Great Lakes down through the Mississippi River Valley, regularly encountered the French between the 17th and 19th centuries. As they interacted with each other, both cultures experienced communication through voice, gestures, body language, ceremonies, signs and rituals. Parents passed language on to children; Native nations physically, spiritually and aurally passed on culture from generation to generation; ceremonial traditions and language were used to interact with the spirit world or served to establish relationship with others who arrived in the midst of a Native community. Frenchmen quickly noticed that Native peoples did not write language except for those who used hieroglyphs and other symbolic and “artistic” means to communicate with each other or with their spiritual realm. Otherwise, Native peoples, the French and other Europeans communicated non-verbally, gesturally and when possible, verbally.

Many Native communities spoke of language through creation stories, aural history and culture. Migration stories explained how diversity of once common languages emerged. For example, when the Quapaws, Osages and Omahas separated, the Quapaws (O-gah-pah) went downstream, the Omaha (O-mah-ha) went upstream, and the Osages (Wa-sha-she) remained in the middle waters leading to a diversification of their languages with time.[2] The Choctaws, the Chickasaws, and the Caddos experienced similar migration separation that also led to communicative diversification. Even tradition stories highlight how languages emerged, evolved or changed. The Lakota tradition, for example, holds that when Ikce Oyate (the Real People) surfaced from the underworld, they found that they no longer knew the language they had spoken before coming through the cave. Consequently, they had to create a new language that no others could comprehend. Among the Choctaws, the crawfish people lived underground without language. Once captured and incorporated by the Choctaws, they learned to speak.[3] These stories, important elements of Native cultures both past and present, help to explain how languages diversified. Europeans and other world cultures possessed similar language stories. Perhaps no example is as well-known as the Tower of Babel story in Genesis 11:1-9, where the people of Shinar strove to build a tower so high that it would make them renowned as its exquisite builders. This heaven-bound tower was never completed. God stepped in, confused the languages of all the workers, and thus hindered their ability to communicate and finish the tower. In the end, the people were scattered across the face of the earth, as were their languages.

Such diversification of languages led to significant communication challenges for groups across North America. But diversity was not just a Native American linguistic phenomenon. When the French reached the New World in the late fifteenth century, France too had numerous languages and/or dialects spoken within its boundaries–Breton, Alsatian, French Flemish, the Langues d’oïl (Norman, Angevin, Saintongeais); the Langues d’Occitan (Limousin, Provençal); even Gascon, Basque, and Italian. Languages varied so much that individuals from one village to the next had difficulty understanding their regional neighbors. As Atlantic travel and exploration began, several of these same languages made it to the New World–sailors fishing for Atlantic Cod spoke Breton or Normand. Still others, in particular those who established Acadie, spoke language forms heard in the south and west central regions of France. The Basques and their unique language made it to the region as well.

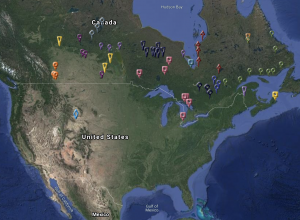

Linguistic diversification was simply a global reality. When Jacques Cartier arrived in the St. Lawrence River Valley in the early sixteenth century, he encountered the region’s Laurentian language with dialects likely connected to Huron, Mohawk or other Iroquoian languages. These languages were related to that spoken by the Cherokees over a thousand miles away in the Carolina region. But languages were far more widespread and diverse than he could possibly imagine. The linguistic map of North America depicts the diversity of languages across the continent. (Click on the map to access an interactive version via the Library of Congress.)[4] As you look at this larger map, notice the location of the Caddoan language in Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas, then in Nebraska, Colorado and Kansas, finally up into the Dakotas. Observe the Iroquoian languages separated again between the Canadian and New York region and the Carolinas and the Smoky Mountains. Further, notice the diversity of languages in the southern Mississippi Valley region. And what about that California coastline? A diversity of languages from north to south along the Pacific shore!

Table 1: Language Families in or near the Mississippi River Valley in the 17th-19th Centuries

| Native Nation | Language Family | Historical Location |

| Cahokias | Algonquian | Illinois Region |

| Cherokees | Iroquoian | Carolinas, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas |

| Chickasaws | Muskogean | Mississippi, Alabama |

| Chitimachas | Chitimachan | Southern Louisiana |

| Choctaws | Muskogean | Mississippi, Alabama |

| Hasinais | Caddoan | Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas |

| Kadohadachos | Caddoan | Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas |

| Kaskaskias | Algonquian | Illinois Region |

| Miamis | Algonquian | Eastern Illinois, Ohio |

| Michigameas | Algonquian or Siouan | Arkansas, Illinois, Missouri |

| Natchez | Natchezan | Mississippi |

| Osages | Dhegiha Siouan | NW Arkansas, Missouri |

| Panimahas | Caddoan | Nebraska |

| Peorias | Algonquian | Illinois Region |

| Quapaws | Dhegiha Siouan | Arkansas |

| Taensas | Natchezan | Louisiana |

| Tamarois | Algonquian | Illinois Region |

| Tunicas | Tunican | Mississippi |

As you look at Table 1 that indicates the language families and Native nations in the Mississippi River Valley as well as the North America map discussed earlier, ask yourself:

- Which groups were related and where were they located?

- How did they become so scattered and isolated?

- How did they communicate with each other or with the French?

Let’s consider the heart of the Mississippi River Valley. The Quapaws’ migration story suggests they were pushed out of the Ohio River Valley by Dutch-weaponized Iroquois in the early seventeenth century. Known as the Downstream People or O-gah-pah, they separated from the Omaha who went upstream, hence the Upstream People or O-mah-ha. Once along the Arkansas River, they told strangers they encountered to call them Arkansas (Akamsea, in the historical record). Thus, the Arkansas River was home to the Quapaws. To the north of the Quapaws lived the Michigameas, perhaps a Siouan-speaking-people, while even farther north lay the Algonquian-speaking Illinois confederacy made up of the Tamarois, Cahokias, Kaskaskias, Peorias and, some suggest, the Miamis.

A few hundred miles away, in northwest Arkansas and southwest Missouri resided the Osages, a part of the Dhegiha Siouan language family that includes the Quapaws, Poncas, Omahas and Kansas or Kaws. Just to the south and west of the Arkansas River lived Caddo-speaking peoples. The Kadohadachos would go on to form the Caddo Nation in the late 18th and 19th centuries with other Caddo-speaking groups such as the Natchitoches and the Hasinai in Louisiana and Texas respectively. The Caddos resided heavily along the Red River, a tributary of the Mississippi, which also supported other Native groups who spoke languages completely different from the Caddos–the Natchez, the Tunicas and the Houmas, among others. Directly across the Mississippi lived the three nations just mentioned as well as the Chickasaws and the Choctaws, two Muskogean language groups, completely unrelated to the Tunicas, Quapaws, or Chitimachas of southern Louisiana. And by the late eighteenth century, a segment of the Cherokees, an Iroquoian speaking group moved into northeast Arkansas.

The Native languages of Canada were also highly diversified when the French entered the region. The image above highlights the various locations where Native languages are commonly spoken in Canada today. (Click on the image to access a related website that allows you to see and hear the languages and the extent to which particular words and phrases differ.)

Review the interactive map above and then reflect on these questions.

- As you click on the different icons and listen to the words, what do you notice?

- What similarities and differences do you hear and/or see?

- How do you think these languages became so diversified?

- Why are words and phrases pronounced or structured differently?

- Why do some words have symbols rather than letters?

Along with the diversity of languages came a variety of individuals with distinctly varied goals and means. French traders and trappers known as Coureurs de Bois, communicated with Native peoples through reciprocity, broken language and gestures to secure “good business,” while missionaries more extensively learned Native languages to spread the Gospel and to “save the souls” of the Indigenous. Often, Jesuit missionaries created dictionaries to apply Native languages to Christian rituals, develop liturgy, and thus have their Indigenous confirmands profess the Catholic faith in their Native language. Still others, especially the Native peoples and the French military hoped that their ability to communicate would help maintain peace, resolve disputes, forge alliances and develop reciprocal relationships. But through these early interactions, creative misunderstanding, a phrase first coined by Richard White in his book, The Middle Ground, played a significant role in how one developed an understanding of the other.[5] As French missionaries moved into the Mississippi River Valley, for example, some Native communities sought alliances with them, in hopes of engaging in trade, but also in hopes of adopting the missionaries’ foreign spiritual power into their own worldview. As the Native peoples embraced the cross, they did so for their own needs, but the priests misunderstood their acceptance as something more–true adherence to the Christian faith.

At times, French missionaries and explorers also misunderstood the reciprocal exchange of gifts. To them, a Native group’s desire for reciprocity meant that they simply wanted goods. But Native peoples abided by a spirit of reciprocity that instilled alliance, faith, trust, and friendship with others through exchange of goods and ceremonial activities. Their tradition was not simply an act of obtaining “stuff,” but a way of developing relationships, demonstrating good will, and keeping bad intentions at bay. Still others felt caught between two worlds, feeling the need to look like the other to “fit in” and communicate good will. For example, the Tunica chief Cahura Joligo was known to dress as a Frenchman so as to live and communicate in both worlds. French Coureurs de Bois, for that matter, dressed similarly to Native peoples and took on their way of life, abandoning their own oppressive French institutions of faith and law, particularly Catholicism, to communicate the freedom and connection they felt to Native peoples.

Missionaries learned Native languages to preach the Gospel; traders learned Native languages to enhance their work and their trade activities; Native peoples learned other languages as well, including French, to help communicate throughout the region. Even young children, Native born or born through intermarriage between French men and Native women, became, at a minimum, bilingual (their Native language and French) and capable of serving as interpreters. Sarasen, the leader of the Quapaws in the early nineteenth century likely spoke both Quapaw and French and perhaps interpreted on some level. Born of a French father (François Sarazin) and a Quapaw mother, he later played an important leadership role in communicating the desperate desires of his people to American officials when faced with removal from Quapaw lands. The Mississippi River Valley was highly multicultural and multilingual in the 17th through the 19th centuries. Communication might flow through multiple linguistic channels–Taensas to Quapaw to Illinois to French, for example. Consequently, the more one could communicate, the better. Indeed, new dialects and language forms emerged to help ease communication–Mobilian Jargon, a mixture of multiple Native languages as well as French, Spanish and even African words served to facilitate trade within the lower regions of the Mississippi.

Though Native peoples did not write as Europeans did, some did express themselves in writing through hieroglyphs, pictographs, and petroglyphs. Many of those “writings” can be seen today, some in Arkansas, but more particularly in the Southwest United States. Ultimately, as the ability to print and publish grew in the New World, Native languages went through an evolution of sorts. The Jesuits had long recorded Native languages so as to advance their ability to Christianize the different communities. They prepared and printed liturgical materials, prayer books and bibles in Native languages. With time, some Native peoples developed the ability to read these European-based texts. But Native peoples also took advantage of printing with none more recognized than the Cherokees who, through the development of Sequoyah’s syllabary, came to publish their own newspaper, The Cherokee Phoenix, and to print news in both their language and in English. Today, Cherokee is the most published Native language in North America.

Of course many other forms of communicative expression were used during the colonial era. Sign talk, for one, supported communication between Native groups, as well as with the French. Ceremony served as an invitation into a Native culture and society, while hospitality communicated good will. Maps, both ephemeral and permanent, communicated location, survival strategies, sacred landmarks, friends and foe. Symbolism in the form of rock art, painted skins, pottery and masks spoke of one’s spirituality and/or history. Even caresses and the carrying of individuals into a village for the first time communicated respect, esteem, and a willingness to share one’s spirit with the other. In short, communication was never limited to what one uttered from her, his or their lips, but was “spoken” in many ways, ensuring that ideas, thoughts, needs, good will, joy, anger, peace, war and so on were expressed.

Nineteenth & Twentieth Century Challenges

Throughout early contact, Europeans assumed that languages were universal and functioned in a manner similar to their own. But by the eighteenth century, some believed that the diversification of Native languages was a “diabolical plot to foil evangelization,” while others felt that it was “another manifestation of the land’s tremendous fecundity,” even “a sign of social disorder,” or that Native languages somehow implied a particular perhaps “arrested” stage of intellectual and social development.[6] Ultimately, Europeans interpreted diversity and the social nature of Native peoples based on their own Eurocentric experiences as white men who were somewhat educated, able to read and write, possessed what they believed were superior war and agricultural implements, and had any number of “riches” at their disposal. Though early researchers came up with a variety of fantastical reasons why Native languages were so varied, the true reason for diversity was simple–migration, evolution of language over decades and centuries, and climate and regional adjustments. These long-term changes, not Biblical scatterings or intellectual arrest, are what led to diversity of languages and people. Nonetheless, questions and assumptions lingered.

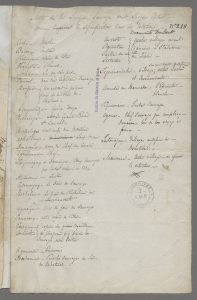

Curious individuals began to collect words of many different Native nations to chart their diverse nature across the continent. Cartier, for example, created the first modest list of words upon encountering Native peoples along the St. Lawrence River.[7] Later collectors pursued more robust lists to compare words for similarities in sounds and meanings. Thomas Jefferson himself requested that individuals gather linguistic information on Native peoples since “knowledge of their several languages would be the most certain evidence of their derivation which could be produced.”[8] Today, one can access many of these lists of words through the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. In this cataloguing of words and simple phrases, grammatical differences among the different Native languages surfaced and challenged scholars. Many had tried to analyze Native American languages from a Euro-linguistic perspective, insisting that language was universal with a common grammatical system. And though some eventually moved away from this assumption and even described Native grammars as sophisticated, rare was it that one might change their perspective of Native peoples as less intellectual than Europeans. For that matter, the word lists were questionable, particularly their phonetically written forms which were based on pronunciation and phonetics of the recording culture (French, English, or even German, for example). Ultimately, this frustrated those who attempted to analyze, further record, or even speak the language.[9]

While many of these collectors sought to better understand Native languages, others had more sinister means to their actions. Many Native nations suspected that gathering lists of their languages was a “wicked design upon their country.” Indeed, some nineteenth century language researchers and groups such as the War Department “studied Native languages so as to identify alliances and differences and determine their implications on Christian conversion or assimilation within the growing American landscape.”[10] As differences emerged, individuals sought to control Native communities, and to even play Native nations against one another in land cession treaties. They intended to solidify, in their minds, that “Native languages and Native minds were as ‘savage’ as popularly imagined.”[11]

By the early nineteenth century, America was in control of the Mississippi River Valley and many Native communities were “in the way” of the white man’s westward progress. In the 1830s, as Americans continued to expand their territory from east to west, these frontiersmen and women encouraged legislators and local officials to side with their interests, creating land cession treaties, and removing Native peoples throughout the Mississippi River Valley into the Oklahoma Indian territory. Consequently, Native communities were forced to give up their land and their traditional life patterns, and to establish an agrarian way of life which deeply threatened their survival. From the early to mid-nineteenth century onward, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, followed closely by the federal reservation system of the 1840s, removed the Quapaws, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Illinois, Caddos, Osages and Cherokees from their lands and into the Indian territory.

As the nineteenth century progressed, Native children, their families and their communities were thrown into further upheaval when young boys and girls were forced into boarding schools to erase their heritage, language and culture from them. These compulsory schools were meant to transform young Native children, to remove from them any hint of their Native culture and language, to “make them white,” even “to kill the Indian and save the man.” This began in earnest in 1886 when the Bureau of Indian Affairs required that all instruction be English-only, with no allowances for Native languages within their schooling. Enforcing English language on young Native peoples was necessary, whites believed, because “Native language could not convey the ‘civilized’ content of English or other European languages.”[12] Similarly French speaking children in Louisiana were forced to stop speaking the French Cajun language or learning the French language beginning in the 1920s in order to make English the official and only language in Louisiana. Though far from the horrendous impact of suppression on Native children, this clearly shows an attempt to homogenize languages across the country, to suppress any language that was not English.

Mandatory boarding school education ended, for the most part in the 1980s, but the damage was done. Generations of Native children and adults minimally spoke their Native language, if at all. The gap between those who could speak it fluently and those who could not progressively increased. By the end of the twentieth century, individuals in their 60s and beyond were the population that had proficient knowledge of the language. But out of this devastation emerged a turning point for language reclamation among many Native communities. Federal laws passed between 1990 and 1993 addressed the need to financially support Native communities so that they might reclaim/revitalize their languages. Additional initiatives have since emerged to promote Native languages. Thankfully today, many nations are on their way to increasing the numbers of Native language speakers within their communities so that their languages will persevere. Sadly, some have not yet found a way to help their language survive.

Into the twenty-first century

Although the work is difficult, things are improving for some Native nations. For one, digital technologies allow Native communities and linguists to more readily access materials for language learning and teaching as well as language perseverance and research. Second, twenty-first century educational technologies such as digital humanities and gamification are taking hold and are allowing creative educational specialists to develop interactive educational materials that can help Native students learn more about their culture and their language simultaneously. One Native designer in particular, Elizabeth LaPensée, has created incredible animation videos and games that help to preserve and promote language, history and culture. Those wishing to learn more can interact with some of these games today via LaPensée’s incredibly rich website. Third, more and more schools offer Native American language courses–through immersion, distance education or face to face teaching environments–to help preserve Native languages. At our own institution, the University of Arkansas, we now offer Cherokee thanks to Lawrence Panther, a citizen of Cherokee Nation, and a fluent speaker of Cherokee language who served as our inaugural Cherokee teacher.

Conclusion

From the 16th through the 19th centuries, Native Peoples and the Europeans and Americans they encountered struggled universally with communication. No one went without some level of communicative interaction–not the linguistically talented Jesuits, nor the French explorers, missionaries and coureurs de bois, not even the different Native communities themselves. But communication did not simply entail spoken words. Gestures, hand signs, drawings in the sand, ceremonial invitations and alliances, objects, maps and symbols all proved vital to communication. Everyone used them and none could communicate without them.

Perhaps no one event portrays this wide variety of non-verbal communication better than the “Great Peace of Montreal.” This event put an end to almost a century’s worth of fighting between the Five Nations of the Iroquois, the French, and their own Native allies. During this great ceremony, some 39 different Indigenous nations from across Acadie, New France, and the Pays d’en haut (Great Lakes region), gathered together to affirm this treaty, making Montreal “the intercultural crossroads of North America.” Throughout this accord, Native peoples acted as autonomous agents, and used their own ceremonies, customs, and rituals as a part of the overarching ceremony. Indeed, as Havard suggests, “Native peoples did not simply give in to European forms of speech and action….at the signing of the Great Peace treaty, French officers clad in the courtly attire of France adopted many aspects of Native protocol such as using wampum belts; participating in condolence ceremonies for the dead; smoking peace pipes; and even dancing in silk stockings and powdered wigs to the beat of Native drums, mirroring the steps and gestures of Hurons, Iroquois, and many other peoples.”[13] Some of the many participants present at the peace accord included Illinois, Ojibwes, Potawatomis, Miamis, and Ottawas. In total, more than 1300 Native peoples attended the event to find a way to broker peace with the French.

Native peoples and their French counterparts needed to cultivate friendship, kinship, cooperation, alliance and collaboration. But communication challenges abounded for all those who attempted to interact with others. Spoken language was exceptionally hard. The Jesuit priest and explorer Jacques Marquette remarked that the Quapaw language “is exceedingly difficult, and I could succeed in pronouncing only a few words notwithstanding all my efforts.”[14] With such challenges, other modes of communication became much more important. One had to rely on context in any attempt to understand one’s counterpart through signs, gestures, words, and other strategies. Ultimately, one could most easily understand the other for practical reasons–trade, alliance, direction. But more abstract reasoning faltered, particularly when it came to religion. Such downturns in understanding led to upticks in misunderstanding, this until spoken language became the norm, though misunderstanding continues to this day…

Post Reading Questions – Now that you have read this first segment of the text, answer the following questions for in-class discussion.

- What modes of communication did Europeans and Native peoples use to “talk” with each other?

- How do you think two different cultures understood one another when they communicated in such unknown ways?

- What attitudes challenged the willingness of Europeans to embrace Native peoples as equal humans?

- What do you make of the diversity of languages on the North American continent? Where did the people come from? How do you think they become so widespread, so diverse?

- What differences in accent and word usage are you aware of across North America? How do you think this happened?

- Certainly Native languages were suppressed in North America but in the United States, so too was French suppressed, particularly in Louisiana. Why?

- By simply reviewing the table of contents for this text, what do you anticipate encountering as it relates to cross-cultural communication during the French colonial period in North America?

- Image of Jacques Cartier stems from The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. "Jacques Cartier" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 19, 2023. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-3c9a-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. ↵

- More specifically, O-gah-pah - “those who went downstream;” O-mah-ha - “those who went upstream;” Wa-sha-she - “those of the middle waters,” or the Osages. ↵

- Sean P. Harvey, Native Tongues: Colonialism and Race from Encounter to the Reservation (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2015), 7; D. M. Dooling, ed., The Sons of the Wind: The Sacred Stories of the Lakota (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 121–22. ↵

- John Wesley Powell, Map of Linguistic Stocks of American Indians. [S.I, 1890] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001620496/. This map reflects years of ethnographic research to determine the location of the historic linguistic families of North America prior to removal. ↵

- Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011). ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 20; On observations of North American linguistic diversity, see Edward G. Gray, New World Babel: Languages and Nations in Early America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 8–27; See also Edward G. Gray and Norman Fiering, eds., The Language Encounter in the Americas, 1492–1800: A Collection of Essays (New York: Berghahn Books, 2000). ↵

- Musée de la Civilisation, Collection du Séminaire de Québec, Fonds Georges-Barthélemi Faribault, no. 218. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 2. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 17-18; Linda C. Jones, "Language Encounters in Colonial Arkansas," The Arkansas Historical Quarterly (Forthcoming in 2024). ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 2-5, 11,& 17; Charles Mackenzie, “The Missouri Indians: A Narrative of four Trading Expeditions to the Missouri, 1804–1805–1806,” in L. R. Masson, ed., Les Bourgeois De La Compagnie Du Nord-Ouest, vol. 1 (Quebec,1889–1890), 336–37. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 5; Henry R. Schoolcraft, “Article V. Mythology, Superstitions and Languages of the North American Indians,” Literary and Theological Review 2.5 (March 1835): 117. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 15; Words uttered by R. H. Pratt. ↵

- Gilles Havard, Montreal, 1701: Planting the Tree of Peace (Montreal: McCord Museum of Canadian History, 2001), 8. ↵

- Reuben Gold Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents [hereinafter JRAD], vol. 59 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1900), 157. ↵