10 After French (and Spanish) Colonialism

The end of Colonialism

Throughout the colonial period, nations along the Mississippi continued to speak their language unabated while some simultaneously spoke a second language such as Mobilian Trade Jargon, or engaged in learning other languages present within their region. Along the Mississippi and its tributaries, some French and Spanish learned Native tongues, while children, the product of intermarriage or intercultural relationships became interpreters both from a familial or cultural stance, or, once older, as official interpreters at times for the French, Spanish and their respective Native community. Missionaries collected Native language elements and created dictionaries and prayerbooks; their Native tutors helped manipulate the text to attempt to make the Christian religion understood. Ultimately, “Colonization resulted in a remarkable degree of linguistic intermixture that provides evidence of close relationships, and in one dramatic instance, a community of individuals with Cree and French ancestry” which led to the mixed language, Michif. And yet, during the colonial period, change happened: dependence on European trade, disease, threats from regional enemies all led many to “seek beneficial relationships with colonists and adapt white ways selectively.” Native communities like the Illinois welcomed traders into their kinship systems; many nations sought alliances, and even welcomed the spiritual power of the missionaries into their midst.[1] However, after the Louisiana Purchase, the United States government took full control and became increasingly hostile to Native peoples as it sought to take away Native lands and push the peoples aside. Consequently, Native nations along the Mississippi and across the continent systematically faced loss of land, language, culture, tradition, community. U.S. governmental actions “imposed rapid, severe, and unprecedented change” on countless numbers of Native peoples and nations.[2] An endless cycle of obstacles impacted Native languages including language repression, removal and diasporization of groups in different directions, as well as forced attendance in boarding schools.[3] These massive U.S. imposed actions were detrimental to Native peoples and communities and led to what one describes as “historical trauma,” that is “’the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding, over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experiences.’”[4]

Removal

Each Native community suffered some form of forced removal as Americans took over. The Quapaws were certainly no exception to this horrific experience. For years, the Quapaws had had good relationships with the French and then later the Spanish. Relationship was established through the sharing of the calumet in a ceremony that communicated good will, changed strangers to friends, or even invited individuals to be in a kinship relationship with the Quapaws. Reciprocity meant that the Quapaws and their French or Spanish allies shared and/or traded goods, offered gifts in response to gifts given, maintained alliance and the like. Granted, these sorts of offerings and activities were not always perfectly achieved, particularly when annual gifts were delayed or medals seemed smaller than what the Quapaws anticipated, for example. Nonetheless, they were gifts that communicated something meaningful. But once Americans took over, all of this changed. The new overseers of the continent would not participate in any traditional rituals of encounter and thus all but ignored the Quapaws and other Native nations, turning their attention to the white farmers along the Mississippi and the rich, fertile land they coveted.

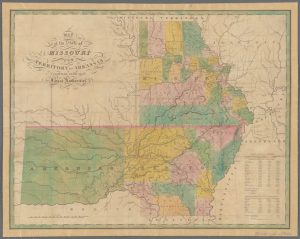

Just before and certainly after the Louisiana Purchase, refugee bands of Native nations made their way to the Mississippi River Valley, in particular the Arkansas territory. When a nation moved west of the Mississippi prior to the Louisiana Purchase, “those decisions had been made by individual families, in conjunction with their Native and European allies.” After 1803 and some 27 years before the Indian Removal Act was signed by Andrew Jackson, movement of some Indians westward was nonetheless a part of U.S. policy. Jefferson believed that the Arkansas or Missouri territory and regions beyond “would for many generations be for Indians, both those already there and any who chose to move West.” But Jefferson was also looking to the future. He wanted white citizens “to have access to the western Mississippi Valley but figured they wouldn’t need it for several generations,” thus leaving most of the West to Native peoples. By the time Americans would need it, “Native people[s] there either would be ready to be assimilated, would move farther west, or perhaps would simply be doomed to extinction,” remarked Jefferson.[5]

At first, the intent was for Native nations to voluntarily move into the Arkansas territory near the Mississippi River, where Cherokees and others had already settled. Indeed, an 1808 land cession treaty with the Osages was obtained to make room for other Native peoples, setting the stage in 1809 for President Jefferson to speak with a Cherokee delegation about available lands in the Arkansas territory. Consequently, hundreds of additional Cherokees moved west from their traditional lands in and around Alabama and Georgia to settle in the Arkansas River Valley. Not surprisingly, the Quapaws greeted these and any newcomers with traditional ceremonies. Ultimately, “Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw men married Quapaw women to enough of an extent to catch the eye of American officials.”[6]

Jefferson’s plan to use the western bank of the Mississippi as a place to send eastern Native nations put pressure not only on the Osages but also on the Quapaws to make room for those to the east. But it wasn’t just for eastern Native nations that the Quapaws found themselves making room. After the Louisiana Purchase, white settlers moved in at an even greater pace and demanded the fertile lands that were claimed by the Arkansas. In short time, thousands of Americans surrounded the five hundred or so Quapaws who lived in the Arkansas territory. Seeking a way to remain in their homelands, these Arkansas Indians offered some of their land in exchange for the right to stay put so that “‘the powerful arm of the US will defend us their children in the possession of the remainder of our hunting grounds.’” Consequently, an 1818 treaty gave some 90% of Quapaw territory (twenty-eight million acres) to the federal government and left them with “a small reservation along the lower Arkansas River, which included their towns,” and the right to hunt in lands ceded to the union.[7] The English botanist Thomas Nuttall met Quapaw Chief Heckaton not long after he had signed this treaty.

“His appearance and deportment were agreeable and prepossessing, his features aquiline and symmetrical. Being told that I had journeyed a great distance, almost from the borders of the great lake of salt water, to see the country of the Arkansa, and observing the attention paid to me by my hospitable friend, he, in his turn, showed me every possible civility, returned to his canoe, put on his uniform coat, and brought with him a roll of writing, which he unfolded with great care, and gave it me to read. This instrument was a treaty of the late cession and purchase of lands from the Quapaws, made the last autumn, and accompanied by a survey.”[8]

Heckaton took the treaty very seriously and viewed the “written treaty as sacred.”[9] But squatting whites were less moved by the paper’s content. Arguing that the 1818 treaty “wasted good cotton land on ‘Savages’ rather than giving it to ‘citizens,’” a new treaty in 1824 forced the Quapaw to cede their remaining lands. The Quapaw leader, Saracen, could only remark: “‘the French were good for the Arkansas [Quapaws], they taught us, they fed us and never mistreated us; The French and the Arkansas always walk side by side. My friend the Spanish came, the Arkansas received them; The Spanish were good to the Arkansas, they helped us and they walked together side by side. The Americans have come, the Arkansas received them and gave them everything they could want, but the Americans are always pushing the Arkansas and driving us away.’”[10]

Unlike their experiences with the French and Spanish, the Quapaws were unable to develop any form of relationship or kinship with the Americans, either “fictive or real.” These English speaking settlers and their government “saw Indians as strangers and possible trading partners, but not potential kin.”[11] As a result, there was no intermarriage to be had between Americans and the Quapaws. Their ability to deeply connect with the Americans, impossible. Cotton was taking over and soon the Quapaws would be forced off of their land not once but twice. In return for the 1824 treaty, the Quapaws were first designated land among the Caddos along the Red River in northwestern Louisiana along with $4,000 in goods, and a $2,000 annual annuity that was to continue for eleven years. Quapaw Chief Heckaton was dismayed: “‘To leave my native soil, and go among red men who are aliens to our race, is throwing us like outcasts on the world. The lands you wish us to go to belong to strangers.’”[12] Expectations were that the Quapaws would merge with the Caddos and thus “’lose not only its ancestral home but its identity as well.’” In June 1825, Heckaton appealed to the territorial governor, George Izard, to postpone removal but Izard refused. Instead, the Governor “appointed Antoine Barraqué as subagent to organize and lead the Quapaws, and Joseph Bonne, of Quapaw blood, to aid Barraqué as interpreter.”[13]

The move to Caddo country took place in 1826 and was fraught with disaster. Unwelcomed by the Caddos, the Quapaws suffered through severe flooding and starvation. In response, Saracen brought one fourth of the surviving Quapaws back to their traditional lands in hopes of renegotiating settlement in the region. Meanwhile, many became squatters near Pine Bluff, Arkansas. They subsequently farmed and hired themselves out “to pick cotton and hunt game for white families.” Assigned one fourth of the Quapaw annuity by Governor Izard, these returned Quapaws “began to use the annuity to lay the foundation for a Quapaw future in Arkansas,” and persuaded Izard to use the annuity to purchase agricultural implements and to fund the education of ten Quapaw boys. Indeed, part of removal included attempts to have Native peoples develop the white man ways which began with “arts of subsistence, teaching the use of domestic animals, agriculture for men, and spinning and weaving for women.” To acquire property, one would have to develop “literacy and numeracy for recording and calculating transactions.”[14] By 1830, Heckaton had brought the remaining exiled Quapaws back to Arkansas. Saracen and Heckaton both pleaded with governmental officials to allow the Quapaws to remain in their traditional lands. In the end, unable to buy their own land back, forced to take refuge in swamps, the Quapaw signed a new treaty in 1833 which granted them 96,000 acres in the Indian territory or today, northeastern Oklahoma, the final move.

At this point, “the Quapaws were marginalized economically, socially, and politically. The Arkansas economy reoriented itself eastward to the detriment of hunting and trading. The number of white farmers increased and so did the number of livestock. By the 1820s, cotton bound Arkansas to the economy and labor systems of the Southeast. The advent of cotton agriculture increased the Quapaws’ significance in the eyes of white American settlers and their government – but as obstacles rather than potential partners. Cotton growers demanded a certain kind of land and the Quapaws had it. This set the stage for their removal.”[15]

The Choctaws also moved before the 1830 Indian Removal Act was signed. In 1820, the Choctaw signed the Treaty of Doak’s Stand, which exchanged traditional Mississippi land for a large segment of the Arkansas Territory. But just as they had disputed the 1818 Quapaw Treaty, white citizens of the Arkansas Territory disputed that of the Choctaws because it included land upon which they had already settled. Thus, in 1825, the treaty was adjusted to include a smaller segment of land more acceptable to the white population. Regardless of the change, few Choctaws emigrated to their assigned region. By 1828, “only eight had reported to the agency, while forty to fifty were living on the Red River, and about 1,000 were living in small villages in Louisiana.” But in 1830, the Choctaws signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek thus becoming the first to be removed to Indian Territory, despite having become productive farmers and taken on aspects of the white man. Unfortunately, as would be seen time and time again with other Native nations forced from their lands, removal for the Choctaws did not go well over its course of three years. During the first year, the Choctaw departure started late and put them in the midst of “the worst blizzard in the history of the region.” The second year, a cholera epidemic devastatingly impacted their people. Only in the third year did their removal go relatively smoothly, given what it was.[16]

By May 1830, drastic, devastating measures for many Native peoples were on the horizon. Edward Everett warned congress in May 1830 that the Native nations “are not cognate tribes,” that they did not speak the same language, nor did they have the same traditions and societal makeup. Indeed, the Cherokee General Council warned “of the consequences of forcing Cherokees alongside those ‘with languages totally different.'” The Cherokees and likely others feared “that ancestrally different peoples would not live alongside one another peaceably, which elevated the importance of recognizing linguistic similarity and difference in the minds of policymakers.” Already, within the Arkansas territory, problems abounded as the “voluntary” Cherokees and Osages battled with another in the Arkansas territory while the Cherokees and Choctaws remained “in a state of hereditary hostility.”[17] Consequently, President Jackson was urged to “create ‘union[s]’ between ‘kindred tribes, connected by blood and language’…to bring together ‘bands, which are connected by language & habits,’” to make for more efficient layout of the Indian territory. Needless to say, Native responses were mixed. The Chickasaws voiced their own concerns about a linguistic make up of removal. They had maintained a distinct identity from the Choctaws, their linguistic kin, for centuries and sought to preserve their national independence thereafter. But in the Treaty of Doaksville (1837), the United States assigned the removed Chickasaws to a district of the Choctaw nation. This foresaw, for Chickasaws, the possibility of “losing their name and becoming merged” into the larger nation. The Chickasaws firmly believed that “there was a considerable difference between the Choctaw and Chickasaw languages,” despite being from the same linguistic family. The Chickasaws insistence upon living separately from the Choctaws “pushed the United States to acknowledge Chickasaw distinctness in 1855.”[18]

Congress passed, and President Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in May 1830 essentially removing thousands of people living east of the Mississippi to the west. This included Muskogees, Cherokees, Shawnees and “all native nations from places that the United States wanted.”[19] The millions of Americans in the east wanted more land, more economically valuable terrain. Native peoples were in their way. Jackson believed that moving the Native people’s westward was for the best. He asserted, “’for what good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studied with cities, towns, and prosperous farms?’” What Jackson wanted to see was Native peoples moving westward “to the wilds of the West to continue their savage life for as long as they could.”[20]

Once forced removal began, for nations like the Cherokees, it boiled down to very limited choices: “dissolve their sovereignty and live within U.S. states, some as fully assimilated white people…[or]…exchange their eastern lands for lands West of the Mississippi, within the Louisiana Purchase.”[21] In other words, move to the Indian Territory and remain as a nation or give up your nation-status and become an American. The 1830s thus saw the dark, devastating period of the Trail of Tears as Native communities throughout the southeast were forcibly removed from their Native lands into Indian Territory.

Prior to removal, the Cherokees did all they could to maintain their sovereignty and remain on their lands. They “centralized what had been a town- and clan-centered government. They created a republic with parallels to the United States and other new republics in the era.” This included “legislative, executive, and judicial branches” as well as adoption of a written constitution in 1827. Further, they “defined clear borders for the Cherokee Nation and outlawed selling land to non-Cherokees.” These changes were made “in ways that fit both their and U.S. citizens’ ideas of how modern nations should function.”[22] But as progressive as these measures were, they would never be enough. Even Sequoyah’s syllabary that represented literacy and autonomy on the part of the Cherokee people could not prevent removal. Indeed, “white-educated Cherokees held up the extraordinary invention as proof of Cherokee civilization, in the hopes of swaying public opinion against removal, while downplaying its obvious rejection of English literacy and its implications for preserving Native sovereignty.”[23] Alternatively, critics saw “volumes of strange characters” as “a form of civilization that impeded potential incorporation” into American society. The Syllabary, as such, “challenged the long-standing assumptions that civilization would bring assimilation and that religious and civil imperatives were one and the same.” In short, the Cherokee syllabary “demonstrated social transformation analogous to ‘civilization,’ but in forms that made clear Cherokee resistance to assimilation.”[24]

The rapidly increasing, “land-hungry citizenry of the United States” threatened many Native communities. The Cherokee themselves fought in every aspect they could to remain on their lands—in federal courts, through newspapers, even “the halls of Congress.” [25] Thousands of women in the northeast, along with US office holders signed petitions and “agreed that the Cherokee Nation had the right to exist in some form where it was.” In the Cherokee Phoenix, editor Elias Boudinot encouraged his people to keep their morale up. Writing in syllabary in the May 7, 1831 edition, he stated: “’Do not let your hearts weaken… Strengthen our commitment to our homeland. Keep plowing and make your fields bigger, and keep building, and keep growing your food for your neighbors and for your children… Make clear to our beloved leaders our determination to hold on to our lands, to not lose our property, our homes, our fields.’”[26] Nonetheless, by 1832, Jackson and others communicated to Boudinot and those who traveled with him to Washington “that the Cherokees’ only choice remained moving west….[for] Jackson’s administration was intent on enforcing the Indian removal act” and ending the Cherokees’ presence in Georgia.[27] Soon, Boudinot’s tone in his writings changed. In an 1832 editorial, Boudinot wrote “’think, for a moment, my countrymen, the danger to be apprehended from an overwhelming white population… overbearing and impudent to those whom, in their sovereign pleasure, they consider as their inferiors.’” Not long after, Boudinot, John Ridge, Major Ridge, and several other Cherokees decided to exchange Cherokee land for movement west as a nation, before all were destroyed by the white men. Most Cherokees disagreed with this decision and expelled Boudinot and the Ridges from Cherokee nation. Nonetheless, on December 29 1835, Boudinot, Major Ridge, John Ridge, and several others “signed the Treaty of New Echota, which exchanged the Cherokee Nation lands in the east for lands in the west and $5 million.” Boudinot and his colleagues felt that the Cherokee Nation’s only chance to survive and to retain freedom was to flee. “Stay and become slaves or go West and remain the Cherokee Nation–to Boudinot, those were the only choices left.” Three years later, federal troops rounded up the remaining Cherokee families and placed them in stockades. Some 20,000 Cherokees and their 2000 or so enslaved people were forced to leave their homes and land to travel hundreds of miles to the Indian territory. Harsh conditions, starvation, disease, and exposure led to the deaths of 4000 Cherokees along this cruel Trail of Tears.[28]

As mentioned earlier, some Cherokees had already gone west in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, “in their pursuit of a life free from white intrusion.”[29] These Cherokees already present in Arkansas were known as the “Old Settlers.” As those from the east were forcibly removed, the two groups reunited and eventually made their way into Indian Territory. Once the survivors of the Trail of Tears reached Tahlequah, they executed Boudinot, Major Ridge and John Ridge for signing the 1835 Treaty of New Echota. Selling Cherokee land as they had done through this treaty was a capital crime among the Cherokees.

Illinois nation members also found themselves forced from their homelands. On October 27, 1832, the remaining Kaskaskias, Peorias, Tamarois, Cahokias and Mitchigameas signed a treaty with the United States in which they ceded all their lands in the Illinois country to the U.S. in exchange for some 96,000 acres in northeastern Kansas, “which were promised to be theirs forever.” Collectively the various communities adopted Peoria as their name. Shortly after signing the treaty, the Illinois were moved west. The linguistically related Miami were also forced to cede large tracts of land in the Ohio region to the United States beginning as early as 1795 in the Greenville Treaty. By their own 1840 treaty with the government, the Miamis were required to leave their land within 5 years. However, because of their resistance to removal, many were forcibly removed in large boats and moved west into the Kansas region in October of 1846. As described by Darryl Baldwin, “An army was sent out to what is now Peru, Indiana, and our ancestors were given 48 hours to collect what they could carry.”[30] This resulted in a split of their nation with some staying in their traditional lands along the Wabash Rivers, having been granted exemptions and allowed to stay. By the 1870s, a second removal occurred from Kansas. Those Myaamia who refused to accept American citizenship were forced into the Indian territory. Today, the Myaamia are distributed in two main pockets–the federally recognized Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, and the Miami Nation of Indiana.[31]

Because some nations moved into Indian Territory during the early 1830s, a Wichita Peace gathering took place on the Red River in 1834, one that “put the lie to Jackson’s claims of Native decline and disappearance.” Osages, Cherokees, Delawares, Senecas, Kiowas and Comanches all came together, all who in varying ways had fought against one another. All understood that they had to get along with each other, “that growing US power made it imperative that they make a safe home in the West,” that peace was a far better alternative to war. Soon enough, Quapaws, Shawnees, Choctaws and Muskogees included themselves in this alliance of “‘perpetual peace and friendship.’” As Quapaw Chief Heckaton remarked, “‘there must not be any blood… unless it be the blood of the Buffalo.’” As he and the others saw it, “joint efforts among Native nations and the very act of resisting together, even when they lost to greater U.S. power, would ultimately allow Native nations to survive the upheaval and losses of the removal era and beyond.”[32] Ultimately, though the U.S. created the Indian Territory, the Native nations alone “made it a workable space for one another in a time of increasing dispossession.” Quapaw Chief Heckaton provided an exacting remark on their situation. “That after the U.S.-Quapaw Treaty of 1824 took the last of their lands, Native peacemaking had created for them a home among ‘my Brothers, the Muscogees, Choctaws, Osages and Senecas’ in Indian Territory.”[33]

But not all nations or all members of a nation left their homeland. Some Cherokees remained in the east; some Choctaws remained in Mississippi as did some Chickasaws. Meanwhile, the Chitimachas of southern Louisiana never left their lands. Members of these and other nations were variously supported by “white neighbors with whom they did business or went to church.” Some managed to keep their land “by gaining individual title to it or retreated onto parts of their lands less desired by white Americans.”[34] Some simply hid. The Chitimachas lost much of their land after the Louisiana Purchase except for land near present-day Charenton, Louisiana. President Franklin Pierce officially declared this Chitimacha land in 1855. Nonetheless, settler violence continued to whittle away at Chitimacha land and people. But by the early 20th century, and thanks to families such as those of the Tabasco company of Avery Island, the Chitimachas were able to secure their land more readily and remain there to this day. Indeed, they have purchased additional lands around Charenton and now own some 963 acres, with some 445 acres kept as land trusts.[35] Among those Cherokees who stayed in the east, early on they were seen “forming settlements, building townhouses, and show every disposition to keep up their former manners and customs of councils, dances, ball plays and other practices. Though meant to “stop being Cherokee,” these Native peoples, now known as the eastern band of the Cherokees, like other Native peoples in a similar situation “kept their identity, and ultimately they would use individual land ownership to keep their lands and retain a Cherokee Nation in the east permanently,” even as most Cherokees were forced west.[36]

Boarding Schools

With nary a grain of dust settled from the forced removals of the 19th century, a new form of hardship and devastation soon emerged—the federal boarding school system. Throughout the 19th century and most certainly by its end, compulsory boarding schools represented yet another unthinkable destructive force on the cultural elements and traditions that clearly distinguished Native peoples from whites. English only instruction was mandated and any use of a Native tongue in school was met with violence and abuse.

Native peoples long had an education system of their own, albeit far removed from what Europeans and later Americans would surmise appropriate for a future life system in white America. But for Native peoples it was ideal for survival, for spirituality, for family and community; for self. Though this type of education varied from community to community, it was “generally founded on oral traditions in which elders transmitted knowledge and skills to younger generations through methods such as storytelling, memory skills, hands-on experience and practice, and prayer.”[37] As Americans pushed westward, these types of practices all but disappeared only to be replaced with nationwide boarding schools. Americans believed their educational system was far superior to that of the Native peoples. If one was to live in America, one had to be educated like the white people.

Boarding Schools were meant to literally discard anything Indian and create a white child. Indeed, that was the goal of U.S. Government officials who sought to change those they could not otherwise defeat. Their established boarding school system was a severe process that “emotionally and spiritually devastated generations of American Indian people, setting in motion a concatenation of repercussions, including cultural genocide and generations of family pain.” Although the federal government thought it was the solution to the “Indian problem,” in truth, “it became an instrument that emotionally scarred generations of innocent children, leaving them and their children, as well, victims of institutionalized cultural genocide.” Terrible things happened in these schools – physical, emotional and sexual abuse, a prison environment, cutting of hair and forced wearing of uniforms, “unceasing unkindness,” hunger, humiliation, punishments for speaking one’s language, wetting the bed, not finishing a meal, and the like. All across the North American continent, these children were “utterly powerless in the hands of a group of people committed to not only controlling one completely, but also to erasing one’s personal and tribal identity.”[38]

European schools for Native children began early enough, with the establishment of the Society for Propagation of the Gospel in New England in the mid 17th century. By the start of the 18th century, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts itself established over 150 missions throughout the colonies. While not quite the aggressive and cruel schools that would follow in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, these schools, nonetheless, sought to whiten Native children and “compromised graduates’ chances of even surviving in their native environment.”[39] As the leadership among the Iroquois commented: “Several of our young people were formerly brought up at the colleges of the northern provinces; they were instructed in all your sciences; but when they came back to us they were bad runners, ignorant of every means of living in the woods, unable to bear either cold or hunger, knew neither how to build a cabin, take a deer, nor kill an enemy, spoke our language imperfectly; were therefore neither fit for hunters, warriors, nor counselors — they were therefore totally good for nothing.” In a savvy jab towards the Americans, the leadership further commented: “If the gentlemen of Virginia will send us a dozen of their sons we will take great care of their education, instruct them in all we know, and make men of them.”[40]

Prior to forced removal from their lands, some Cherokee children went to Brainerd School in Tennessee, run by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). The curriculum focused on English, math, geography, history and Christianity. The school also taught “proper” gender roles—boys farmed and learned carpentry; girls learned cooking and dressmaking. Some of the Cherokee nation accepted this form of education, western economic values and the like. These white-oriented Cherokee elite “believed they were on the way to creating a ‘civilized’ Cherokee nation, or at least state, within the Union.” Consequently, the ABCFM strove to educate those children they hoped to incorporate into the new American society. The ABCFM “declared its faith in the gospel to change ‘heathen’ Indians into ‘civilized’ Americans, for ‘Christian principles only’ could ‘transform an idle, dissolute, ignorant wanderer of the forest into a laborious, prudent and exemplary citizen.’”[41]

Some of the Cherokee children were put into the position of becoming “cultural brokers” between their Native nation, the schools and the federal government. Through a collection of letters written by several girls, aged 9 to 15, it appears that they soon identified themselves with their Cherokee Nation but also with the Christianity of their respective teachers. What is striking is that girls were called upon to write letters to their family, to the government and to their teachers’ families as well. In so doing, they developed interesting, albeit unfortunate perspectives of their own people. For example, one 12-year-old wrote “I think they [the Cherokee] improve. They have a printing press and print a paper which is called the Cherokee Phoenix. They come to meetings on Sabbath days…yet a great many bad customs [exist] but I hope all these things will soon be done away. They have thought more about the saviour lately. I hope this nation will soon become civilized and enlightened.”[42] Some even wrote letters that showed the influenced shame they felt for their people, and for their lower rank in society. In one poignant letter written by a 9-year-old to the President of the United States, she wrote: “Sir, we heard that the Cherokees were going to send you a mink skin and a pipe. We thought that it would make you laugh; and the Scholars asked our teacher if they might make you a present and she told us that she did not know as there was anything suitable in the whole establishment. Then she looked among the articles of the girls society and told me that I might make you a pocket book. Will you please accept it from a little Cherokee girl aged nine years.”[43] For all of the girls, Coleman argues, they were “victims, exploited or at least manipulated by both their own families and the missionaries….[they] saw themselves as helping their families to build a new kind of nation, one that could resist white demands for removal.”[44] They sought a way to advance their society, but also to preserve their land and community. In the end, they could not stop progression towards the Trail of Tears that began some 10 years later.

As the 19th century progressed, boarding schools became more severe. Captain Richard Pratt led the federal government’s resolve to convert Indian children to white kids. A former commander over the Fort Marion prison for Indian prisoners of war, Pratt believed it best to “convert abandoned military forts into boarding schools and then implement an educational program based on a military model.”[45] Thus, his first school would be the Carlilse Indian School which was established in 1878 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. By 1902 there were an additional 90 schools spread across the continent. No matter the school, Pratt’s hopes were that a Native child would “lose his identity…give up his tribal relations and to be made to feel that he is an American citizen.” As he saw it, “the sooner all tribal relations are broken up; the sooner the Indian loses all his Indian ways, even his language, the better it will be for him and for the government.”[46]

The government was adamant that Indian children be re-formed. And while the early years did not overly push children to attend schools, by 1892, Congress enacted legislation permitting government officials to use force if Native parents attempted to prevent their children from going to these schools. Ultimately, children were hunted down, taken from exemplary parents and elders, forced onto trains, and placed in boarding schools hundreds of miles away from their homes. Parents were denied rations or even jailed until they turned their children over to the authorities. This horrendously tragic nightmare continued for many years culminating in “neglect, hunger, disease, homesickness–even suicide….[and] little tombstones at boarding schools…” not to mention the unmarked graves that continue to be found even into 2024. Once imbedded in these government schools, reform efforts were cruel. Children’s hair was cut, a cultural blow that normally meant distinct things in a child’s Native tradition–perhaps cowardice or grief over the loss of a loved one. Children were scrubbed raw to remove “germs” and “lice” and other dirty bits that the white leaders of a school feared coming near. They were threatened, beaten, belittled, shamed in every manner possible. Mouths were washed out with soap when a Native word was spoken. They had to take on the religion of their school; no allowances for their own religion or spirituality. Some ran away, only to be severely punished if caught. Some were forced into isolation in a dark attic, with little food for days at a time. Barbed wire fences and barred windows and doors enhanced the feeling of imprisonment. They had to march in step, stand at attention, respond to bugle calls, bells, and whistles.[47]

For a time, Native nations of Indian Territory had their own school systems, but the 1898 Curtis Act “authorized the Interior Department to seize 995 tribally controlled schools.” This take over, including the over one hundred schools run by the Choctaws, led some tribal schools to became federal Indian boarding schools. The quality of education plummeted once the schools passed out of tribal control. “The curriculum shrank from twelve to eight grades; school was in session nine instead of ten months; students, rather than staff, did custodial work, cooking, and maintenance; entrance exams were discontinued, making the academies less competitive.” Under the tribal system, the Cherokee’s literacy rate was nearly 100 percent, “13 percent higher than the U.S. national average” in the late 19th century. But by the late 1960s, the Cherokees witnessed a 40% decline in literacy among their people. To be clear, “the theft of their school systems were national tragedies, staggering losses of capital and autonomy, whose costs would be borne by succeeding generations of Indians.”[48]

The expectation of this forced education was to develop “laborers or domestic servants,” if such jobs could be found once they left the school system,’ what did clearly occur was that once a child left the school and returned home, they no longer seemed to fit in, a repeated scenario that harkens back, even, to Pierre-Antoine Pastedechouen, the young Montagnais boy who was sent abroad to learn the French language in the 18th century. The young lad was “thoroughly ruined by his six years in France.” When he returned to his Native village, he was fluent in French, Latin and the Gallic culture but had lost fluency with his own language. His absence also removed from him any knowledge of the lands and traditions important to his Native culture. His people were ashamed, Antoine ostracized. He died of starvation in the woods–lost to his people and of little use to the French.[49]

Boarding schools witnessed the death of complete generations of Native language speakers. Stories were no longer told; memory skills no longer relied upon; prayer and hands-on work, dissolved; language severely crushed. New generations of language speakers failed to emerge as “boarding schools disrupted the intergenerational transmission of language and culture.”[50] For many, learning English was a path to survival, a hope for becoming a part of the American economy but at the expense of language loss, not to mention loss of culture and tradition. Even where schools were run by a Native community, at times, “because English was believed to be a more effective means of securing political, economic, and social success,” the Native teachers sought to instill in their pupils that “English was a language of greater worth,” than their own language.[51] As one elder of the Chickasaw community stated, “Why speak [the language] if we’re in a different atmosphere, a different world, a white world?” Consequently, it was not unusual for some parents to believe that speaking English or avoiding the Native language would “shield them from abuse associated with speaking an indigenous language.”[52] Indeed, many last generation speakers were “beginning to internally oppress the language, because of cultural shame, by refusing to pass it on to their youth.” As one anonymous Miami commented: “When I was young I asked my grandfather to teach me Miami and he told me that life would be too hard for me if I learned to speak the language.”[53] And yet, grandparents and elders from many a Native nation who would say to their children and grandchildren, “Don’t ever be ashamed of your language, don’t ever lose it.”[54]

As boarding schools continued into the 20th century, some took note and through the Meriam Report of 1928, expressed condemnation for the federal boarding school system. Calls for their termination ensued. By the 1930s, under oversight of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, some boarding schools were closed and replaced with better educational institutions, day care schools and the like. Unfortunately, many harsh schools remained in operation. But awareness was there, and within a few decades, many across the nation came to recognize a need to provide better education for all peoples in the United States.

Beginning in the 1960’s, Congress began to pass legislation to assist Native nations to regain control of education among their children. Through the Higher Education Act of 1965, Native nations could develop tribally controlled colleges and universities. In the Indian Education Act of 1972, funds were provided to increase graduation rates and to support curriculum and support services development for Native Americans. The Native American Programs Act (NAPA) of 1974 was designed to “promote the goal of economic and social self-sufficiency for American Indians.”[55] Less than 20 years later, the federal government created the Native American Languages Act (NALA) of 1990 that established the federal government’s role in helping to preserve and protect Native languages. This policy was clearly a huge departure from education policies that had inflicted such pain and devastation for over a century. And too, those responsible for the development of this act were not federal officials but “local on-the-ground actors that the policy would indeed directly affect” such as the Indigenous congressman Daniel Inouye of Hawaii.[56] Consequently, the 1990 NALA “formally declared that Native Americans were entitled to use their own languages” in business, schools, education and so on.[57] Indeed, this unprecedented policy “recognized the connection between language and education achievement and established an official, explicit federal stance on language.” This same act also reaffirmed the important relationship between language, culture and academic achievement among children. As section 102 of the policy states, “‘the status of the cultures and languages of Native Americans is unique and the United States has the responsibility to act together with Native Americans to ensure the survival of these unique cultures and languages.'” The policy further encouraged individual states to support this act and the inclusion of Native languages in state institutions.[58] Thus Public Law 102-524, signed by George H. W. Bush, was clearly meant to better assure the survival and continued vitality of Native nation languages.

Two years later, the 1992 NALA, also signed by Bush provided “appropriations and provisions for community language programs; training programs; materials development and language documentation.” Through this Act, grant funds could be secured by eligible tribal governments and Native American organizations to support language revitalization programs such as language assessment, planning and program design, program implementation and language reclamation in Native communities.[59] The Esther Martinez Native American Languages Preservation Act of 2006 was meant to expand upon these offerings and provide for the revitalization of Native American languages through Native American language immersion programs and language nests for children under age 7, with a focus on the Native language as the primary language spoken in these nests. This Public Law 109-394 also provided for education for parents and teacher training all in hopes of developing language proficiency and fluency in the target language.

Most recently, the Native American Languages Act of 2022 provides an additional string of efforts to enhance the learning and usage of Native American languages across the nation. Otherwise known as the Durbin Feeling Native American Language Act of 2021, it was named in honor of the late Cherokee, Durbin Feeling who has been recognized as the “largest contributor to the Cherokee language since Sequoyah,” and who “advocated tirelessly for Native language and revitalization efforts.”[60] President Joe Biden signed this act into law on January 5, 2022.

Native nations have created or are in the process of creating language programs to revive, reclaim and even persevere with language learning and language use. Thus, “language revitalization is creating a shift in the conceptualization of speaking a heritage language from something that someone does or a desirable skill set that someone has, and into something that someone is.” In many Native communities, those who speak the language have become Native nation treasures.[61] In 1999, for example, Chickasaw Nation created the Silver Feather Award in recognition of those Chickasaws who “have committed their lives to the preservation and revitalization of Chickasaw language, culture, and life ways.” Recipients are considered “a Chickasaw treasure who is held in the highest regard by the Chickasaw Nation.”[62] Among the Cherokees, a similar recognition has emerged. For his efforts at preserving Cherokee language and culture, Durbin Feeling was named a Cherokee National Treasure. Indeed, Cherokee National Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. described him as “a modern-day Sequoyah” who has led the Cherokee nation to do all it is currently doing to revitalize and ensure perseverance of the Cherokee language.[63] As a result, Feeling is “the first signatory of the Cherokee Language Speakers Roll,” a list of honored Cherokee speakers that continues to increase as individuals develop their language skills.[64]

Reclamation

Some suggest a bleak outlook on languages, with “less than 20 languages spoken by tribes in the United States…projected to survive another 100 years.“[65] No doubt Covid certainly impacted languages when it took out far too many elders, far too many fluent Native speakers who were vulnerable to the virus’ impact on their community. But rather than discussing language death, many Native communities are finding ways to rejuvenate, reclaim, and persevere in teaching their languages to their community and beyond. As the linguist Mary Hermes has stated: “Localized language learning, and revitalization efforts are at the heart of what is happening in local communities.” Indeed, “the only thing that actually has reversed language shift in the past is community members, deciding, often for identity reasons, to use the language.”[66] Many Native peoples, in fact, view their language “as healing, a key to identity, spirituality, and a carrier of culture and worldview.” Thus, “whereas the term language revitalization emphasizes the restoration of the language, language reclamation is concerned with people who are reclaiming their languages and, through that process, beginning to heal themselves, their families and their communities”[67] Many have come to recognize the magnitude of language loss and have taken strides to pursue language reclamation on varying scales. Today, some are taking courses on their reservation while others are pursuing courses online or even at institutes of higher education that offer Indigenous language courses. But one also sees dramatic changes in local education as well, with many taking advantage of grants provided by the federal government to enhance opportunities for teaching both children and adults their Native language. Numerous nations have taken great steps in preparing materials and educators for enhancing their languages. What follows are just a few significant examples from several Native communities that resided on or near the Mississippi River or in the Arkansas Territory during the colonial period.

Here you can read a stories of how the Cherokees valued COVID vaccinations to preserve their people: https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2021/01/04/953340117/at-first-wary-of-vaccine-cherokee-speaker-says-it-safeguards-language-culture

COVID-19 Has Made Teaching The Cherokee Language Even Harder, December 18, 2020 Fluent Cherokee Speakers Are Eligible For Early COVID-19 Vaccinations, January 4, 2021 Coronavirus Victims: Fluent Cherokee Speaker Edna Raper, August 20, 2020

Chitimachas

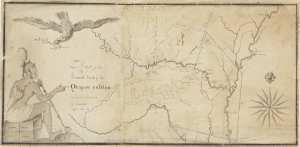

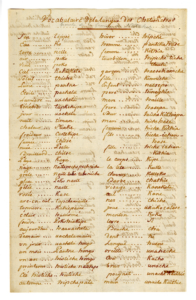

The Chitimachas of southern Louisiana have been engaged in language revitalization over the last 30 years. Their language is unique in that it is an isolate, unrelated to any other language that once was spoken in the region. Unlike several nations along the Mississippi, particularly those in the Illinois region, Chitimacha was not preserved by any religious community, the Jesuits for example. However, with Thomas Jefferson’s push to record vocabulary lists across the southeast, herein was the beginning of documenting the Chitimacha language.

The first known record of Chitimacha language stems from an 1802 list of words completed by Martin Duralde, today housed at the American Philosophical Society Library. When Duralde recorded the language, he did so utilizing French phonetics and French definitions. By the end of the 19th century, any further work among the Chitimacha fell under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of American Ethnology that researched Native cultures and communities beginning in the mid to late 19th century. In the early 20th century, the linguist John R. Swanton became interested in working with the Chitimacha language and worked directly with Chief Benjamin Paul who is considered “the person most responsible for the survival of the Chitimacha language today,” as well as with Mrs. Delphine Decloux Stouff, Paul’s niece.[68] Morris Swadesh expanded on Swanton’s work and made a number of wax cylinder recordings of these Chitimacha speakers in the 1930s. He subsequently preserved some 200 hours of spoken Chitimacha language.

Revitalization began in the 1980s when the Chitimacha first learned of the immense number of documents relevant to their language that existed in the northeast. In 1986, the Chitimachas received a package from the Library of Congress that contained digitized copies of the wax cylinder recordings of language interviews that had taken place with Paul and Ducloux in the 1930s. As those present listened to these sound files, for many, this was their first time to hear the Chitimacha language since no speakers of Chitimacha were still alive. Aside from these wax cylinders, the Chitimachas also obtained thousands of pages of field notes devoted to their language as collected by linguists, Swanton and Swadesh. Some of this material also came from the American Philosophical Society Library.

After opening a casino in 1992, the Chitimachas used part of the revenue to create their nation’s cultural department and to begin work on language revitalization efforts. As a result of their hard work, the Chitimachas now teach the language six weeks after birth and continue this into the K-8 curriculum at their tribal elementary school. The Chitimachas also offer night classes for tribal members. Because of their hard work, the Chitimachas utilize their language to provide the “opening prayer and the Indian Pledge of Allegiance” at many public events.[69] In 2007, the Chitimacha won a significant international grant competition from Rosetta Stone to create language learning software in the Chitimacha language. The software was officially released in 2010, and is now provided free of charge to every member of the Chitmacha nation. It is also used in the school curriculum.[70]

Miami-Illinois

The motivation behind awakening the Miami-Illinois language began with the research conducted by David Costa at the University of California. Through his research, Costa was able to reconstruct phonological and morphological elements of the language which helped reclaim Miami-Illinois at ground zero. Unlike the Chitimachas, written records on the Miami-Illinois language go back over 300 years beginning with Jesuit missionaries who lived among the Illinois and Miamis in the late 17th century. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, linguists gathered further material on this language resulting in “a large body of religious texts recorded by the Jesuits and approximately 50 traditional stories and historical narratives,” not to mention various word lists and other texts recorded over the last three centuries.[71]

Miami nation member Daryl Baldwin became infatuated with the idea of learning Miami and awakening what was a dormant language. Recognizing that there were not any Native speakers of Miami-Illinois, this “first major attempt at Myaamia language reclamation began” out of the deep interest of Daryl and his wife Karen who decided to homeschool their children so to learn Myaamia.[72] Though majoring in wildlife biology at the University of Montana, he switched majors and followed the path of Native American linguistics so that he could further his research and interests in the Miami language. Thus, Baldwin took “linguistic responsibility,” committing himself to not only continue to learn his Native tongue but to share it with his children.[73] Baldwin commented: “I remember feeling a sense of loss but also a sense of responsibility when I learned of the status of our language.”[74]

With his direction, the Miami Nation of Indiana began to reclaim the language began in the mid 1990s with a language camp offered in 1995 near Peru, Indiana. This “family-oriented language camp” offered opportunities for language learning for both adults and children. Baldwin served as the camp’s language instructor and interacted with numerous high school aged youth “who took a personal interest in the language.” In 1996, the Miami tribe of Oklahoma received a language grant from the Administration for Native Americans to train language teachers and begin to further reclaim the language. Baldwin served as their instructor and in conjunction with Julie Olds, “began laying the groundwork for the community effort toward language reconstruction in Oklahoma for years to come.”[75] And in an effort to unite both the Miamis of Oklahoma and those of Indiana, an agreement was drafted to collaborate on language reclamation. The compact was signed in 1997 and “called for the establishment of language committees in both Oklahoma and Indiana.”[76]

From 1995 to 2000, summer-long programs for adults and children took hold. Though just beginning the language teaching and learning journey, language activists soon recognized that “language reclamation was more of a community and social issue than it was a language teaching issue.” That is, “helping the community understand why it should take on such an effort and gaining community support were equal if not greater challenges than teaching the language itself.” But these men and women also recognized that without speaking elders, time was needed to “properly reconstruct the language and learn the cultural context and knowledge systems of the language reflected.” Thus, research had to continue to reclaim the language and the culture.[77]

In 2001, after having reached out to the Miami University of Ohio for collaboration, Baldwin created the Myaamia Project with its mission being “to preserve, promote, and research Miami Nation history, culture and language.”[78] Indeed, the reclamation project was clearly aimed to “’raise [Miami] children with the beliefs and values that draw from our traditional foundation and to utilize our language as a means of preserving and expressing these elements.’” Language, Baldwin remarked, “is not only a form of communication, but is even more so an essential element of community building, and of knowing a people’s history and values.”[79]

This tribal initiation, placed within an academic setting means that those involved “would have the resources and capacity necessary to respond to the research needs of the Miami Tribal community.” Working with the college of Arts and Science, the Provost and Student Affairs, this “created the opportunity for research and educational collaboration resulting in mutual benefits for both the university and the tribe.” In January 2013, the Myaamia Project transitioned into an official university center called The Myammia Center which today includes offices focused on education and outreach, language research, cultural ecology, as well as technology and publications, all devoted to Myaamia language and culture. Ultimately, the purpose of the Myammia Center is “to make available to the community what is learned about the language and culture through its research….a knowledge sharing entity committed to transmitting knowledge of language and culture to the community through educational programs and online resources.”[80]

Part of the Center’s research has included digitizing old 17th and 18th century texts to become a part of cultural and linguistic revitalization among Native peoples. Through the transciption and translation of at least two Miami-Illinois dictionaries, those of Jacques Gravier and Jean-Baptiste Le Boullenger, a digitized dictionary is well under way. Such efforts have already created “‘language life’ for the people who spoke these languages.”[81] Today, Myaamia is spoken as a second language by a small but ever-increasing number of nation members. Though the speaking ability is at an individual functional level, already the language is used at a more community level and appears in written form in publications and signage or can be heard at various events. It is also seen and heard in digital form on websites, and in other forms of social media. The Miamis are certain that the language use will continue to grow as the reclamation journey continues.[82]

Dhegiha Siouan – Osage and Quapaw Reclamation

The Dhegiha Siouan language was spoken both by Quapaws and Osages as well as the Kaw, Ponca and Omaha throughout the colonial period. All suffered a tremendous decline in language speakers after the American takeover. While the Quapaws have taken strides to digitize materials and offer classes to adults of Quapaw nation, the Osages have expanded their offerings. Various Osage Elders such as Leroy Logan have spoken about the importance of language for a long time. Because of their wisdom and the diverse efforts of many within the nation, the Osages created the Osage Language Department in 2003 that supports language learning both among its people, among other Dhegihan nations and in nearby schools. Already, this nation has witnessed students advance in their language skills towards fluency with some 300 currently enrolled in their language program courses offered. Osage teachers have also offered language courses at Pawhuska High School since the 2009-2010 school year. Some of these students, now graduated, are listed as language teachers among the Osages. Indeed, as of 2024, Osages is taught in five public schools in Osage County with more to be included in the coming years. Currently among the Osages, there are 15 to 20 speakers who can “speak or pray” at gatherings and cultural events. Undoubtedly more will soon follow. And while the teachers are primarily Osages, there are some who are also Quapaw and Ponca. They too have developed their Dhegiha language skills and thus can share their language with others of the Dheigha language family.

The Osages have a rich approach to developing language skills among their children and adults through such activities as youth language fairs, digitized materials, online dictionaries, an Osage font for writing in the Osage language, as well as mobile apps such as Sonny Goes to School, an interactive tool that provides access to language learning tools complete with sound, text, quizzes, and other types of activities to help students learn. As their website states, “We will continue to make an aggressive effort to revitalize the Osage language. Because of what we have experienced, we know it can be done. We cannot quit; our future depends upon it.”[83]

Chickasaw Chikashshanompaˈ Reclamation

When the Chickasaws began to reclaim their language, they did so at a time when some several hundred fluent Chickasaw speakers still lived among them. Though this was the case in 1994, in this 21st century, there are fewer than 75 speakers, most of whom are older than 55 years of age.[84] Nonetheless, the work to persevere and develop future fluent speakers is well underway.

Early on, the Chickasaws recognized that they had to begin work to maintain their language for future generations. In 1967, for example, the governor of the Chickasaw nation, Overton James, commissioned a Chickasaw language dictionary, a “family affair” in which his mother and her husband worked. By 1973, they had created the Humes Dictionary, meant to serve as “a resource for language study” among the Chickasaw peoples. By 1994, additional work added to this dictionary and a concerted effort to teach the language began. First came community language classes in the late 1990s. But after the turn of the century, the Chickasaws made tremendous strides towards more fully reclaiming their language. The nation secured a 2006 grant from the Administration for Native Americans and subsequently established their Chickasaw Language Revitalization Program in 2007. The mission of this program: “We believe that our language was given to us by Chioowa (God), and it is our obligation to care for it: to learn it, speak it and teach it to our children. The Chickasaw language is a gift from the ancestors for all Chickasaw people. The job of the Chickasaw Language Revitalization Program, simply put, is to help people access that gift.”[85]

Shortly after founding the Language Revitalization Program, the Chickasaws founded the Chickasaw Nation Language Department in 2009 with full-time employees, a language committee and numerous fluent speakers who serve as instructors in the various programs offered. Though they are a small percentage of the Chickasaw population, “fluent Speakers of the Chickasaw language are placed at the center of the Nation’s community and culture…their centrality to Chickasaw identity has been formalized through a growth in recognition within the community and the creation of employment positions available solely to Speakers.”[86]

The Chickasaws have long valued speaking their language. Already their many efforts through various services and programs have paid off. The Chickasaw nation estimates that “over 1000 people have some passing knowledge of the language, and around 5000 participate in Chickasaw language programs annually.”[87] Undoubtedly these numbers have enlarged through the success of numerous programs including youth language activities—language camps and language clubs; free language classes for adults in the community; high school and university courses; and a Master Apprentice program.

The Chickasaw language master-apprentice program pairs a master or fluent speaker of Chickasaw with an apprentice to help the language learner gain knowledge of Chikashshanompaˈ through full immersion. An additional Adult Immersion program invites learners to dedicate a year’s worth of study, 10 hours a week, to develop their Chickasaw language skills. There is even a self-study program to help learners develop their knowledge of Chikashshanompaˈ at their own pace. This website and a complimentary mobile app provides words, phrases, videos and songs in the target language. A downloadable workbook accompanies this website.

For younger learners, the language club Chipota Chikashshanompoli (Youth Speaking Chickasaw) meets once a month. Activities through total physical response and song, among others, help students more richly experience the language. Learning the language in this environment supports students who compete annually at the Oklahoma Native American Youth Language Fair. For the even younger learners, ChickasawKids.com is available to help children learn more about their people, culture, language and history. This website provides them with various interactive activities to enhance their learning.[88]

There are also opportunities for individuals to learn Chickasaw through their exceptionally rich streaming media system, Chickasaw.tv. Within this website, individuals can gain access to language learning videos, historical and cultural information. It is tremendously informative and inviting. What’s more, in 2015, the Chickasaw Language Department partnered with Rosetta Stone to develop a Rosetta Stone-based Chickasaw language learning tool in conjunction with fluent Chickasaw speakers. In this unique application, Chickasaw is taught through a day in the life of a Chickasaw family with modern day application. Ultimately learners can work through the lessons provided at their own pace and learn important ways of interacting and conversing in Chickasaw in their own daily life.

Chickasaw author Kari A. B. Chew has found that “family was a primary source of motivation for participants’ involvement in language reclamation efforts…[with] intergenerational perspectives on the importance of Chikashshanompa’ to Chickasaw families.” Specifically she observed that the older generation wanted to “ensure Chickasaw survivance through the language,” while the middle generation felt it was their “responsibility to pass the language to their children,” and the youngers yearned “to speak Chikashshanompa’ and [develop] consciousness of Chickasaw identity.”[89] As one Chickasaw elder remarked: “[The language] is something we need to hang on to because we were given our language by the Creator. If we don’t keep speaking our language, it will be gone. Other tribes have lost their languages. [Our language] is part of our culture [and] our heritage. [It] is what separates us from everyone else.”[90] Indeed, when Chew heard her Native language, Chikashsanompa’, first spoken, she commented: “I learned to say the phrase, “Chikashsha saya” (I am Chickasaw). While I had spoken these words many times in English, my life was forever changed when I said them in the language of my ancestors. I realized that my identity as a Chickasaw person was not adequately expressed through English. The far-reaching impact of colonization and the enduring pressures of assimilation had prevented me from knowing my language, and thus, fully knowing myself. Reclaiming this ability became a driving force behind my desire to learn my heritage language.”[91]

Cherokee Reclamation

Durbin Feeling is considered the greatest contributor to reclaiming Cherokee language in the 20th and 21st centuries. Born in Little Rock, Oklahoma in 1946, Feeling served in the Vietnam war, and afterwards completed a BA at Northeastern State University and then an MA in Social Sciences from UC Irvine. Cherokee was his first language and only in elementary school did he begin to learn English. At age 12 he learned to read Cherokee syllabary. After the Vietnam War, he created the first Cherokee-English dictionary in 1975, and after completion of his education, he went on to teach Cherokee at the University of Oklahoma, the University of Tulsa, as well as the University of California. But his efforts did not stop at the classroom. Feeling also played a significant role in seeing Cherokee syllabary digitized as a font for use on word processors, mobile phones and, of course, internet sites. As a result, Cherokee, as described in this video, has long been and remains on the cutting edge of technology. Because of his unwavering efforts, Durbin Feeling was named a Cherokee National Treasure, and first on the rolel of honored Cherokee language speakers.

Here are two stories on technology and the Cherokee syllabary: Gmail Sends Message In Cherokee, November 20, 2012 Apple Put Cherokee Language On iPhone, December 28, 2010

Because of Durbin Feeling’s and others efforts, Cherokee language learners have innumerable opportunities to learn or expand their Cherokee language expertise. The very recently opened Durbin Feeling Language Center provides any number of courses and programs to learn the language. The Cherokees offer language camps, community classes, an immersion school, a Master Apprentice program, as well as a teacher training program to help expand the knowledge and expertise of those who will go on to teach their language to others. Courses are variably offered face-to-face or online to reach the greatest number of people. Universities are helping as well. Cherokee is now taught at Northeastern State University, the University of Oklahoma, Rogers State University, and the University of Arkansas, among others. Cherokee nation provides materials for language learning including digitized posters and activities, an online dictionary, and a wide variety of videos on language and culture available on their Cherokee Nation YouTube channel, and through Osiyo TV, an award winning streaming video site that also offers language learning opportunities in addition to superb videos on the culture and history of the Cherokees. In short, the overarching goal of all of the Cherokee nation’s language offerings is “the perpetuation of Cherokee language in all walks of life, from day-to-day conversation, to ceremony, digital and online platforms such as social media.”[92]

Recently, the Cherokee Nation established a relationship with the Mango Language Learning website to offer Cherokee language lessons through public libraries. Two Cherokee language program specialists, Anna Sixkiller and John Ross, helped to create some of the chapters that are offered within the Mango website. According to Cherokee Nation member Roy Boney, “There are a few other Cherokee language apps, but most of them are basic word lists with colors or animals. This one is getting into how you interact, talk and speak back and forth, and the grammar notes explain why the language is the way it is.” To continue to build the website, a linguist was assigned to work with the Cherokee Nation and to develop the lessons so that they made the most sense to the learner. As Boney describes it, “You can see the phonetic and tone pronunciation. You can actually record your own voice and compare how you’re pronouncing it to how they’re saying it…You can have the pronunciation slowed down if you need to hear it better. So it’s got quite a lot of features in it.” Further, Mango also includes cultural and grammatical notes and tidbits to help learners understand language roots and how the language functions. The Cherokee language program is free to users provided that their library has a subscription to it. Boney added, “one of the reasons why we liked this project when we got approached with it was the fact that it does give people an incentive to go to the library, and that’s an underused resource in a lot of communities.”[93]

Technology and Native Languages

Language teaching and technology have gone hand in hand for centuries–yes, centuries! Think about it: thousands of years ago, the Native peoples of the French region picked up such technologies as paint, straws, brush sources to communicate to their spirit world by drawing magnificent bison, deer, and cats. Early Native peoples in the Americas did much the same. As the decades and centuries advanced, Egyptian hieroglyphs were etched into stone to communicate something to others. Alphabetical and symbol-based words evolved and they, too, were etched into stone, and still later written onto parchment and paper. Fast forwarding into the 19th century, new technologies played a part—film visually captured individuals speaking to each other, with captioned cards between scenes; wax cylinders and records captured the voices of Native peoples, preserving their sounds and phrases for others to hear. After World War II, reel-to-reel tape and the need to teach languages became even more prevalent, evolving into different teaching styles. With time emerged the cassette tape, VHS tape, CD’s, DVD’s, and now, the Internet, streaming video, phone apps and gaming–you get the picture! Language teaching no matter the language–French, Arabic, Cherokee, Potawatomi–has evolved over the centuries, and technology has accompanied this teaching every step of the way. The Rosetta stone initiatives, while not games, were developed in conjunction with Native communities, the Chitimachas and the Chickasaws, for example. These tools provide visual, verbal and textual access to the language. Mango is expanding opportunities for learning Cherokee and Potawatomi, among others. Fonts are available; one can write in a Native language through email, on word processors, on the Internet.

Today, pedagogically sound strategies that accompany varied technologies are helping Native American communities further their ability to reclaim, maintain, and teach their languages. But Native individuals are also working together to create Indigenous cultural games to help one learn more about Native culture and tradition, as well as elements of language and societal issues. Part of this development includes calling on Indigenous peoples to collaborate in the design and creation of such material.

Elizabeth LaPensée is one distinguished developer of Native games. An Anishinaabe, Metis and Irish woman, she has created many interactive tools including the educational 2D adventure game intitled When Rivers were Trails. This game was developed in collaboration with the Indian Land Tenure Foundation and the Games for Entertainment and Learning Lab at Michigan State University. Some 24 different Indigenous writers provided stories for this game while artistic work by Weshoyot Alvitre and music by Supaman round out the application’s sophistication. As LaPensée describes it, “You are an Anishinaabe in the 1890s who is displaced from Fond du Lac in Minnesota and travels to California due to the impact of allotment acts on Indigneous communities….You must balance your wellbeing making use of foods and medicines you gain through trading, hunting, and fishing to make the journey by foot, train, or canoe along the waterways.”[94] This game gives users “an understanding of both the policies shaping the relationships between the federal government and tribal nations and Indigenous perspectives of history.”[95]

Another fascinating game by LaPensée and her team of developers is Coyote Quest, a point-and-click adventure game that stems from Coyote’s Crazy Smart Science Show, a series on Aboriginal Peoples Television Network focused on in Indigenous science presented through Coyote’s “tricky style.” And very much à propos to this text is the game Dialect, “a story game where players participate in an isolated community whose language emerges and must be protected from loss as they establish values, interact, and face challenges through modular world-building.”[96]

Others have also created games that can help users learn language or work through cultural and societal issues. On the Path of the Elders allows users to explore “the story of the Mushkegowuk and Anishinaabe Peoples of North-Eastern and North-Western Ontario, Canada and the signing of Treaty No. Nine (James Bay Treaty) in the indigenous territory known as Nishnawbe Aski Nation (People’s Land).” The goal of this interactive game is to provide users “an understanding of the historical times in which Mushkegowuk and Anishinaabe peoples signed Treaty No. Nine, and how this treaty has impacted the lives of our people.” Part of the design of this game includes Elder knowledge that is rapidly disappearing.[97]

Another game entitled Finding Victor is a virtual reality game aims tells a compelling story of an Indigenous youth striving to overcome homelessness and to stabilize his life. This game focuses entirely on Victor, “an Indigenous artist that has recently lost a close friend which has been the catalyst to a downward spiral into partying, criminal activity and ultimately homelessness.” Any individual who plays this game serves as “a friend that has been given the task of following Victor, solving clues and uncovering his journey back to support.”[98]

One final example of many is the mobile phone game Never Alone that follows Nuna and her arctic fox as they journey through the Alaskan Terrain. Their goal is “to discover the source of a blizzard harming her home village.” Throughout the game, users play as either Nana or the fox to solve the challenges they face.[99]

Final Word

Be it during the colonial period, or the results of the American takeover, or during today’s period of reclamation, for Native nations, “peoplehood and perseverance are sustained through Native languages in every body of work,” including artifacts, gestural language, published texts, landscape symbolism, digital applications, conversation, prayer, and legal documentation. Consequently, the importance of a Native language is without question: “The sine qua non of Indigenousness is Indigenous language. Each language encodes ancient memories as well as current meanings. Its parts of speech reflect a people’s unique way of categorizing phenomena. Along their etymological routes, its words have picked up freights of unstated knowledge…A language is a complex package encoding a unique worldview that no other language can really represent.”[100]. Thus, any effort of reclaiming language and persevering in expanding its use contributes to a Nations continued existence. In the words of Wilma Mankiller: “If we have persevered, and if we are tenacious enough to have survived everything that has happened to us to date, surely 100 years or even 500 years from now, the future generations will persevere and will also have the same sort of tenacity, strong spirit, and commitment to retaining a strong sense of who they are as tribal people.”[101]

Explore the following:

While not all nations of the Colonial Mississippi timeframe were mentioned in this chapter or even in this text, there were and are many that interacted with the French and/or the Spanish but that also faced destruction at the hands of disease, removal, the boarding school system and the like. Based on what you have learned from this text and especially this final chapter, take some time to exam other Native Nations of the colonial Mississippi River. What was their experience in the 19th and 20th centuries? How are they reclaiming their language? Consider the following

- Tunicas

- Natchez

- Houmas

- Taensas

- Biloxis

- Coushattas

- Caddos

- And the list continues…..

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 14. ↵

- Kari A. B. Chew, “Family at the Heart of Chickasaw Language Reclamation,” American Indian Quarterly 39, no. 2 (2015): 156, FN7. ↵

- Jenny L. Davis, “Language Affiliation and Ethnolinguistic Identity in Chickasaw Language Revitalization,” Language & Communication 47 (2016): 100-01. ↵

- Chew, “Family at the Heart,” 156, FN 7. ↵

- Kathleen DuVal, Native Nations, A Millenium in North America (New York: Random House, 2024), 348. ↵

- Key, “Outcasts,” 274. ↵

- DuVal, Native Nations, 444-46. ↵

- Thomas Nuttall, Journal or Travels into the Arkansa Territory, during the Year 1819 (Philadelphia: Thomas H. Palmer, 1821), 93-94. ↵

- Key, “Outcasts,” 280. ↵

- DuVal, Native Nations, 446, FNs 9 & 10; https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/indian-removal-2595/. ↵

- Key, “Outcasts,” 276. ↵

- DuVal, Native Nations, 447. ↵

- Laura Hinderks Thompson, “Historical Translation of Antoine Barraque Manuscript,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 40, no. 3 (1981): 221-222. ↵