7 Misunderstanding and Deception

Different levels of interpretation exist–literal or word for word interpretation, idiomatic interpretation, and interpretation that can be easily, creatively misunderstood or misinterpreted. Thus, surface meaning versus deeper meaning. Think about it: Have you ever interpreted something one way when it actually had an alternative meaning? Has someone ever misinterpreted something you said or did? Take a moment to reflect upon your own experiences as you prepare to read this chapter.

Richard White remarked that “diverse people adjust their differences through what amounts to a process of creative, and often expedient, misunderstandings….They often misinterpret and distort both the values and the practices of those they deal with.”[1] During the colonial period, instances of such misunderstanding emerged through one’s exposure to ceremonies and events witnessed by both Native peoples and Europeans. Calumet ceremonies, acceptance of images, adoptions, marriages, baptisms, sacrificial funerals, even the common strategy of gift giving—each had attached “meanings to these practices that the other did not fully comprehend.”[2] Intercultural accommodations, creative misunderstandings, “new combinations of meanings just to get along.”[3] No matter how you phrase it, there was a distinct disconnect at times between what one culture understood, heard or saw and what the other actually meant, said or displayed.

For starters, communicating one’s spirituality to a non-believer proved difficult: “It was one thing to say something so simple as a name, altogether another to convey the abstract, metaphysical knowledge that would lead to an understanding of Christianity” or even Native spirituality.[4] Robert Morrissey amplifies the point of how creative misunderstanding operated in communication between Native peoples and Jesuit missionaries. His premise is that two different generations of Jesuits encountered the Illinois. The first generation was made up of Fathers Claude-Jean Allouez and Jacques Marquette, the two earliest priests to encounter the Illinois in the mid 1600s, followed later by the second generation of priests that included Fathers Jacques Gravier, Gabriel Marest, Pierre-François Pinet and others who worked with the Illinois after the 1690s. As this second generation became better skilled with the Illinois language, they recognized that previous beliefs about the acceptance of Christianity among the Illinois were incorrect and misunderstood, and that many more differences existed between the Illinois culture and their own than had been realized. For example, Marquette and Allouez assumed syncretism, a wedding of Christianity with Native traditions that convinced them that the Illinois worshiped the Christian God. But once the second generation of Jesuits arrived, they determined that the Illinois were not as Christianized as earlier Jesuits believed them to be. Their various “idolatrous” activities–manitous, spiritual traditions and shamans–disrupted more concrete access to Christianity. As a result, intercultural relations between the Illinois and the missionaries “declined from remarkable harmony and almost universal accommodation at the outset to great discord and division in the 1700s.” Ironically, “better communication was the end of an optimistic era of religious syncretism in this most remote Jesuit mission in North America.”[5]

Allouez first made contact with the Illinois in 1666, when several of their people made their way to his mission of St. Esprit that was located in Chequamegon Bay, an inlet of Lake Superior, located in modern day Wisconsin. Seven years later, Marquette met the Illinois on their own lands along the Illinois River and founded the Mission of the Immaculate Conception among them in 1674. Both Allouez and Marquette were certain that the Illinois were perfect for Christianization, “a fine field for Gospel laborers, as it is impossible to find [a group of Native people] better fitted for receiving Christian influences.” Unlike many other Native communities, the Illinois were not hostile to missionaries, they were open to prayer, and even “promised to become evangelists in their own right.”[6]

The early Jesuits identified what they thought were helpful parallels between Illinois spirituality and Christian practices. Allouez noted the Illinois’ recognition of one spirit–the “maker of all things”–very much like the overarching God in Christianity. He commented that the Illinois “have hardly any superstitions and are not wont to offer Sacrifices to various spirits, as do the Outaouacs and others,” even that the Illinois sometimes fasted, much like Catholics. And Allouez certainly witnessed, and happily so, the Illinois place “an image of Christ at the center of one of their great feast celebrations, offering food to the icon as a sacrifice.” Some Illinois even burned tobacco at the Christian altar (much like priests swinging incense) or prayed to the church structure itself, pointing their oratory “to this house of God, and speak[ing] to it as to an animate being,” after which they threw “tobacco all around the church, which is a kind of devotion to their divinity.” Ultimately, these various gestures “suggested an idiosyncratic, but positive, embrace of Christianity.” As Allouez remarked: “They honor our Lord among themselves in their own way.”[7]

Allouez and Marquette had “an exaggerated sense of similarity” between Illinois spirituality and that of Christianity. Since the Illinois “worshipped only the Sun,” these early Jesuits confidently believed that a shift in their worship away from the sun to the Christian God would be simple, and would result in complete conversion of the Illinois. But as Morrissey argues, the two Jesuit priests and the Illinois spent very little time together. Neither side ever developed adequate communication strategies beyond a superficial level. As such, “they could not perceive the extent of their differences to begin with, for they fundamentally could not understand one another.” As Morrissey states: “The accommodations that Indians and Jesuits shared in the early years—the baptisms, calumet ceremonies, and myriad improvised Christian rituals—were the stuff of creative misunderstanding.”[8]

Marquette and Allouez both trusted that the Illinois perfectly aligned with Ignatius of Loyola’s call—“to accommodate Christianity to Native life.” Both believed it “impossible to find [a people] better fitted for receiving Christian influence.”[9] But with little ability to richly communicate with the Illinois, and without a more profound knowledge of Illinois spirituality, these Jesuits did not recognize that the Illinois belief system far surpassed the realm of simplicity. While they may have thought the Illinois came to hear explanations, and longed to fully convert to Christianity, simply presenting a picture in the chapel excited the Natives peoples’ curiosity but perhaps more because of the art form itself rather than the Word. The French assumption that the Illinois Great Manitou could be easily shifted towards the Jesuits’ one God was simply creative misunderstanding. Indeed, the early Jesuits used the Illinois term manitou to convey Catholic concepts. But they did so not knowing its full range of uses. Kiche Manitou, for example, may have meant Great Spirit, a term the Jesuits relied upon to indicate the one Christian God. But Kiche Manitou could also mean demon, or even great serpent.[10] For that matter, Gravier’s Illinois/French dictionary contains a number of examples of the term manitou attached to what he interpreted as “idolatrous worship of animal spirits, such as the serpent, beast, or bird.” One manitou, 8aban8a, “was a fire divinity and ‘made the fire furious,’” while another “’speaks to me in my dreams.’” Using the term manitou “might cause Indians to think of the Christian God in unacceptable ways.”[11]

Mastery of any language depends on extensive, deep immersion with the language and culture and authentic interaction with others. Consequently, as the second generation of Jesuits more fully addressed their language skills, and spent far more time with the Illinois, they better understood Illinois culture and the “differences that divided them, differences they had ignored—or simply missed.”[12] Gravier’s greater linguistic immersion among the Illinois nation revealed many differences, leading the Jesuit father to attempt to “disabuse them of the senseless confidence they have in their manitous.” Gravier and other late 17th and early 18th century Jesuits chose to dismiss the early accommodations provided by Marquette and Allouez and instead, “spent energies trying to make Christianity in Illinois more orthodox.”[13] Ultimately, both the Illinois and the second-generation Jesuits “realized the imperfections of early accommodations, the ambiguities in early translations, the true distance between Indian spirituality and Christianity.” As such, improved communication unveiled the presence of misunderstandings among the early Jesuits and destroyed in some instances, “new meanings and through them new practices—the shared meanings and practices of the middle ground.”[14]

Priests from the Séminaire de Québec also misunderstood the extent to which Native peoples embraced Christianity. In 1699, these Seminary missionaries ventured into a Tunica village that lay some four leagues inland from the Mississippi, along the banks of the Yazoo River. Although that day the Tunicas received them with an “indescribable joy,” the missionaries saw desperation all around as men, women, and children were suffering terribly from an epidemic that had struck their village. Immediately, the missionaries baptized several infants who were near death. They also baptized a chief after having taught him some of the mysteries of Christianity through an interpreter. They gave him the Christian name Paul and were certain that “during the little time we saw him, he spoke to us with a judgement and the mannerisms of a very good Christian. We were amazed to see such sentiments in an Indian who had never been introduced to the light of faith. He died not long after he was baptized.”[15]

Sometimes, even after minimal exposure to the Christian faith, missionaries referred to select Native peoples as “very good Christians.” Shortly before arriving at Gravier’s Illinois mission earlier in 1698, the Seminary priests came upon a Native hut and were “consoled to see a perfectly good Christian woman” within one. When they later met Chief Rouensa, father of the well-known Christian convert Marie, they too declared him a “good Christian.”[16] But no missionaries had ever worked among the Tunicas. Other than Father de Montigny’s rapid teachings and baptisms, the Tunicas had no concept of Christianity. A newly baptized Tunica man suffering from a fatal disease—how did he so quickly gain the title “Good Christian”? In all probability, physical movements that visually aligned with Christian gestures and verbalizations likely caught their attention.[17]

Catholic missionaries looked for particular gestures, movements, and actions that they believed visually demonstrated and thus communicated one’s Christian faith to another. But Native spirituality also stressed performance, particularly when interacting with one’s manitous and sacred ceremonies. This exterior physical expression “released the transformative power contained in ritual knowledge and in relationships with manitous. Ritual action helped maintain balance and order in the world.”[18] For example: “Each morning he [the Natchez chief or Grand Soleil] arose, he went to the door of his home, extended his arms, and turned to the east to greet the rising sun as if to give thanks for a new day, much like a priest who lifts upwards his hands to give thanks for the blessed body and blood of Christ.”[19] Consequently, when missionaries saw such physical evidence–bowing to the cross, holding a crucifix, closing eyes as one listened to prayer, reciting words prayerfully, or lifting one’s hands or eyes skyward–they assumed “that Native individuals were praying to the Christian God and thus were very good Christians.” To be clear, bowing, praying, closing one’s eyes, or even holding a sacred object were just as much Native in style as they were a part of Christianity.[20] But miscommunication could also work in the opposite direction. The Florida Indians, for example, assumed the French Huguenots worshipped the sun because of the way they lifted their eyes skyward. “The Indians, who had listened attentively, thinking, I suppose, that we were worshiping the sun because we always had our eyes lifted up to Heaven, rose up when the prayers were ended and came to salute Captain Jean Ribault.”[21] While the French likely interpreted correctly what they believed the Florida Indians were thinking, the latter probably did misunderstand what they saw.

Crosses and Columns

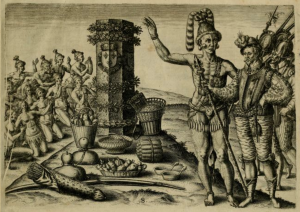

Native peoples and the French differently interpreted crosses and columns. Cartier, the first known Frenchman to plant a cross on Native soil, placed the Christian symbol on a point at the entrance of a harbor somewhere in the Québec region. On it one also placed a shield that contained the royal fleur de lis as well as the words Vive le Roy de France.[22] Once erected, the Frenchmen kneeled, joined hands and looked towards heaven. Of course, this caught the Native peoples’ attention, for once they saw this thirty-foot cross, “Chief Donnacona pointed to it from his canoe, made a cross-like sign with two fingers, and launched into a ‘long harangue,’ sweeping his hand over the surrounding land ‘as if he wished to say that all this region belonged to him, and that we ought not to have set up this cross without his permission.’” In an effort to curb their assumed fears, Cartier explained by signs that the cross served as a landmark for their eventual return and their subsequent distribution of more trade goods. The Stadaconans “‘made signs to us that they would not pull down the cross, delivering at the same time several harangues which we did not understand.’”[23]

But the discussion was far from over. Donnacona’s tone, his stance quite a distance from Cartier’s boat, and the absence of any semblance of joy signified troubled understanding of just what Cartier intended by planting the cross. And though the French explorer “attempted” to ease Donnacona’s fears by offering gifts, Cartier only intensified the situation when he siezed Donnacona’s two sons, Domagaya and Taignoagny, and took them away to France presumably to prepare them to serve as interpreters in future visits to the region.

Others also witnessed various reactions of Native peoples to the Christian symbol. In the Pays d’en Haut, Marquette described the Miamis’ response to a cross that had been previously erected in their village by Jesuits: “When I visited them, I was greatly Consoled at seeing a handsome Cross erected in the middle of the village, and adorned with many white skins, red Belts, and bows and arrows, which these good people had offered to the great Manitou….They did this to thank him for having had pity On Them during The winter, by giving Them an abundance of game When they Most dreaded famine.”[24] When LaSalle and his men visited a Quapaw village in 1682, they erected both a cross and a column decorated with the coat of arms of Louis XIV. The French relied on these symbols to proclaim their alliance with the Quapaws but also to signify God and King’s oversight of the region. While the Quapaws may have somewhat believed that the King would fight any who attacked them, they also believed that spiritual powers existed within the column and the cross. Consequently, they danced around both objects, pressed their hands onto them, and rubbed their bodies as they had done when they first welcomed their French guests.[25] To further honor these spiritual gifts, they built a palisade around them.[26] In 1698, as Saint-Cosme and his Seminary colleagues passed through the village, they too planted a cross. Weeks later, as they traveled anew by the Quapaw village, they saw an additional cross that the Quapaws had planted along the banks of the Mississippi. Likely the Quapaws used the Christian symbol to mark their terrain, to emphasize their relationship with the French, and to exhibit the new spiritual French manitou in their region.

The cross certainly could have served as a point of reference for Cartier, or as a powerful spirit for the Miamis, or even as a sign of union and alliance between the Quapaws and the French, but it was not a statement of obedience. In other words, Native peoples were their own masters, and adoption of the Christian symbol simply expressed “a desire to tap into French spiritual power.” Native peoples believed “spiritual power was the foundation for material, military, and social power.” A warrior, a chief, or an individual who proved successful “was a person with strong spiritual power.” Likely, those strange men in black who traveled with Cartier or on their own accord; these men who planted crosses, made gestures, carried around silver chalices, and looked upward to heaven, they too were perceived as having spiritual power, enhancing many a Native nation’s desire to have a missionary among them.[27] Indeed, the Quapaws considered the Jesuit Father Paul du Poisson as a messenger for Wahkondah, a Paniangasa![28] Consequently, some Native communities welcomed the introduction of the cross as an essential gift meant to enhance their spirituality, particularly since the arrival of European disease and increasing warfare “made it imperative that they assimilate other peoples and their spiritual power in order to sustain a viable nation.”[29]

Quite possibly, the Quapaws interpreted the cross as the Frenchmen’s sacred pole. In Quapaw society the sacred pole was a traditional hallowed element that “symbolized tribal unity through the union of male and female aspects of life as reflected in the reciprocity and mutuality of Quapaw kinship.” Within their tradition, the sacred pole “was a symbol of chiefly authority derived from Wahkonda,” that “compelled honesty of those who approached it. Since the honesty and integrity of chiefs was paramount to their leadership, a man was unable to become a chief until he had struck the sacred pole and taken an oath to lead the nation well.” Ultimately, the Quapaws used the cross as such a sacred object. “Hunters used it to define their territory, and the nation used it as a sign to other Indians of their alliance with the French. The cross redefined Quapaw sacred space as it beckoned friends and warned enemies.”[30]

Both cultures understood that the cross had spiritual importance. But Native peoples also believed that a decorated secular column planted by Frenchmen contained spirits as well. During their first visit to the Florida region, Ribault and Laudonnière erected a column that was meant to symbolize the Frenchmen’s claim to the region along the Florida coast. The coat of arms carved onto the column would declare the land in the name of the King of France. During their return voyage to the region, the Frenchmen visited the stone column and discovered that the Native peoples found it to be “a thing to which they ascribed great significance….We found it to be crowned with magnolia garlands and at its foot there were little baskets of corn which they called in their language ‘tabaga tapola.’ They kissed the stone on their arrival with great reverence and asked us to do the same. As a matter of friendship we could not refuse…”[31]

Making a sacrifice to a cross or building a reverential palisade around it served as an offering to the symbol’s spirit. Placing flowers on a column and rubbing either the statue and themselves was a way of celebrating the spirit’s presence and bringing the spiritual powers from the object into one’s being. Ultimately, “assimilating new spiritual ideas and practices with those they already had increased diversity in their spirit world.” Such actions “added a religious dimension to connections with other peoples.” Otherwise, they did not remove anything from what was present within their spiritual tradition nor did they become pure Christians. Native peoples and Frenchmen, be they missionaries or not, simply had “two distinct and different ideological interpretations of [the same] religious objects,” differences that were subtle and could be “easily overlooked.”[32]

Misinterpretation of Reciprocity

Aside from spirituality and sacred objects, misunderstanding abounded in other ways. Within the Tamarois village, for example, a particular Indian named “la Tortue” or “the Tortoise” asked the Seminary priests Fathers Saint-Cosme and Bergier to come and baptize him rather than the Jesuit priest, Father Pinet. Months before, la Tortue and the Cahokias, also present in the Tamarois village, made an accord with the Seminary missionaries and invited them, not the Jesuits, to build a mission within their community. Soon after, the Seminary missionaries built their mission and hoped to begin their work. But Pinet’s language skills allowed him to more quickly connect with the villagers in comparison to the slower, linguistically challenged Seminary priests. Nonetheless, La Tortue preferred otherwise. His people had given gifts to the Seminary missionaries “so that they might in turn teach them of Christianity.” They “gave the Seminary missionaries land on which to build a home and a chapel [and] Native slaves to serve them. Such gifts were the first steps in a relationship that required reciprocal actions to maintain this union of trust and friendship.”[33]

La Tortue likely longed to have deeper interaction with the Seminary priests and not the Jesuits. He expected reciprocal responses from these priests to whom they had given land, but neither the Jesuits nor the Seminary priests understood this. They simply fell into a troubling competition for first rights to the Tamarois people. For that matter, la Tortue may have creatively misunderstood the different Catholic missionaries, that they possessed or believed in different gods or manitous. Being ill and perhaps unsatisfied by the Jesuit Pinet’s Christian spirit, La Tortue may have alternatively sought the power of the Seminary priests’ manitou. While these different missionaries likely felt they were both equally Catholic and worshiped the same god, to la Tortue, they were “strange and powerful men” who “lived separately, dressed differently (the Jesuits wore black robes; the Seminary priests, black robes and white collars or blancs collets), and approached the Tamarois differently as well.” Bergier was aware that the Tamarois sensed a difference between the two types of Catholics: “The French and the Indians perceive quite well that despite what one says, that we and the Jesuits are the same thing, we are two nonetheless.”[34]

Offering land for the subsequent establishment of a mission along with expectations for teaching or even baptism in return was one example of reciprocity. But more often than not, the French misunderstood the importance of reciprocity, particularly in the institution of gift exchange. Father Gravier visited the Quapaws in late October 1700. Like others before him, the Jesuit priest was greeted with great respect and hospitality. The Quapaws hosted Gravier with a fine feast of “green Indian corn seasoned with a large quantity of dried peaches . . . a large dish of Ripe fruit of the Piakimina [persimmon], which is almost like the medlar of France.”[35] To reciprocate their hospitality, Gravier gave the Quapaws “a present of a little lead and powder, a box of vermillion wherewith to daub his young men, and some other trifles.” But the chief also invited Gravier to stay “because he wished with his young men to sing the Chief ’s calumet for me.” Gravier declined their invitation: “I thanked him for His good will, saying that I did not consider myself a Captain [a person of distinction], and that I was about to leave at Once.” Gravier’s response pleased his French colleagues, but for the Quapaws, it “was not very agreeable.”[36] Gravier knew of the calumet ceremony’s importance but interpreted their offer to celebrate the sacred ceremony as an attempt “to gain presents from me.”[37] His refusal “left the Quapaws dissatisfied.” They needed Gravier to celebrate the calumet with them “so as to fit [him] into the ‘system of real and fictive kinship,’ so that he might participate in shared, familial responsibilities.” Ultimately, Gravier’s refusal and inaccurate presumption of “greedy Quapaws” affected his ability to enter more intimately into their society. As a stranger, it was risky to not participate in the calumet ceremony, as “enemies refused to exchange in mutually beneficial ways.”[38]

Twenty-five years later, two Quapaw men asked the Jesuit Father Paul du Poisson “to adopt them as his sons, explaining that the adoption would mean that when they returned from the hunt, each adopted son ‘would cast, without design, his game at my feet.’” According to these two young men, they were not trading but, instead, were giving him sustenance in the form of wild game. Nonetheless, “the men would expect the priest to invite his ‘sons’ to sit down and join his meal,” or perhaps the next time they interacted, the “father might give him some vermilion and gunpowder.” To Du Poisson, this seemed a lot like trading. But the Quapaws saw giving and receiving as evidence of respect and friendship. On another occasion, Father Du Poisson smoked the calumet with a chief who visited his home. The chief gave du Poisson a painted deer skin. When the Jesuit priest asked what was expected in return, the chief replied, with insult, “I have given without design . . . am I trading with my father? But a few minutes further into the conversation, the chief happened to mention that his wife could use a little salt and that his son was out of gun powder.”[39]

The French did not fully understand that reciprocal exchange–sharing the calumet, participating in the strike-the-pole ceremony, reciprocal gifts and feasting–permitted the French to enter the Quapaws’ world and gain access to their hospitality, kinship system, alliance and resources. Instead, they only saw greed in how Native peoples put such importance on material reciprocity. But if an alliance was to stand, the French were equally obliged to care for their relations. Indeed, the French, and later the Spanish and Americans, missed the point, becoming in George Sabo’s words, “inconsistent kin.” Europeans and Americans failed to understand that among Native nations, there was no “strict distinction between the material and the spiritual, and especially between the sacred and the non sacred,” that “all aspects of life, and certainly all human affairs, were penetrated by a sacred dimension of reality.” This was most prominently expressed in the Quapaws’ institution of reciprocity where “practical obligations and responsibilities carried a sacred and inviolable sanction.”[40]

The Seminary priest Father Bergier refused to provide goods to the Tamarois who, he believed, simply wanted to accumulate “stuff”. But a crisis struck his embattled mission. The Jesuits beckoned the Tamarois away from Bergier’s mission to the newly established Kaskaskia village just across the Mississippi River near modern day St. Louis. Thus, to convince the Tamarois not to cross to the other side, Father Bergier “engaged in the institution of reciprocity, as he interpreted it, and countered Chief Rouensa’s gifts to the Tamarois with some five hundred coups de poudre (powder charges) and other goods.” Because of the Cahokias’ help, he “provided gifts for their support as well—a kettle, four additional pounds of powder, a pound of colored glass beads, vermillion, and a dozen knives.” Angered by Bergier’s impromptu gift giving, the Jesuit Father Pinet accused Bergier of “putting a plague into the mission . . . working contrary to God’s glory and thus, responsible to God for the wrong he had done to the Tamarois, and for the lost converts who would not witness the good example of the Christianized Kaskaskias.” But Bergier was certain of his actions, particularly when he learned that “the Tamarois had never wanted to leave and had only feigned this desire to get presents from him.” As he put it: “Thank God…my conscience was relieved.”[41]

Bergier had not wanted to offer gifts as enticements for the same reasons that Gravier and du Poisson had not wanted to exchange gifts with the Quapaws. But to keep the Tamarois in his mission and their village, he mimicked Native-like reciprocity to convince those who were leaving to stay. Though he saw his gifts as material enticements, nothing more, the Tamarois interpreted this as Bergier’s desire “to strengthen their relationship, to develop deeper trust one for the other, to ensure their alliance.” No matter the creative interpretation by either side, in this instance, both received what they individually desired—resistance to the Jesuits, receipt of gifts, or the Tamarois’ continued presence within their village and Bergier’s mission.[42]

In general, Bergier wanted unwavering devotion to Christ without the Tamarois receiving goods in exchange. However, the Native community wanted reciprocal gifts “to serve their community, spiritual items to support their expanding spirituality, and most important, a relationship with Bergier, strengthened through the reciprocal actions of giving and receiving.” But Bergier, who was long concerned that the Tamarois “view us as rich traders rather than as poor people [and] disciples of Christ,” as merchants rather than as representatives of God, resisted only until he desperately wanted or needed the Tamarois to stay put.[43] Bergier did not understand that reciprocal offerings both established and strengthened relationship and kinship between individuals and cultures with mutual reciprocity at the core of this institution. That is, gifts created “‘peace and a sort of conditional friendship . . . [that] to break off the gift giving [was] to break off the peaceful relationships.’”[44] Indeed, the sharing of goods represented “generosity, cooperation, and concern for mutual welfare.” Goods were not owned by one individual but were meant for all within the community. Kinship, whether through the culture itself or gained through the sharing of the calumet and reciprocity, essentially meant that no one went without food, clothing, or safety. And despite his surly nature, even la Mothe de Cadillac commented that bountiful hunters “profit[ed] the least from their hunting.” When they returned to the village, they hosted feasts for friends and family and distributed their hunting fare throughout the village. Those present were “permitted to appropriate all the meat in the canoe of the hunter who has killed it, and he merely laughs.”[45] So important was reciprocity to Native communities that they made “presents of all their possessions, stripping themselves of even necessary articles, in their eager desire to be accounted liberal.” But doing so required regular “restocking” of goods. Hunting and gathering, crafting, trading, and the like helped Native communities to acquire more goods and share them. Bergier, on the other hand, chose “to give them generally all of my provisions, and then live off of their alms,” thereby destroying his ability to participate in any manner of reciprocity particularly since the arrival of goods from France was so shaky and unpredictable.[46] Ultimately, Bergier had no material reinforcements to use in any gestures of trade. In short, “circumventing reciprocity created a wall between Bergier and the Tamarois that weakened trust [and communication] between the two cultures.”[47]

Misinterpretation of Land

When Cartier planted the cross discussed earlier, it is difficult to know just what the Native peoples really said to him. But suggesting that they were concerned with Cartier “claiming their lands” is truly Cartier’s own interpretation, though clearly its presence concerned Donnacona and his people given their great hesitancy to come close to Cartier. In truth, Native peoples did not own land but most certainly had regions of importance to them in terms of hunting, sacred burial grounds, ceremonial plazas, homes and the like. Consequently, several missionaries were reciprocally offered use of land from various Native communities. The chief of the Cahokias, for example, offered Father Saint-Cosme land within the Tamarois village on which to build a house and a chapel. A reciprocal exchange was expected—”land for teaching; a chapel and a place to learn more about the white man’s manitou.” The young Jesuit Father du Ru exchanged a knife and other goods with the Lower Mississippi Bayougoulas for land behind his fledgling church structure that never came to fruition. Once again, a reciprocal exchange occurred–help to attempt to expand his mission in exchange for access to the white man’s religion.[48]

When Native peoples welcomed strangers into a village, they hoped to develop strong relationships that strengthened the Native community. As such, the exchange of goods or even an offering of land in exchange for other goods or access to a Christian manitou were all a part of that reciprocal process. No matter the exchange, “a reciprocal response was key in building the newly established relationship.” Despite these reciprocal events, some Frenchmen believed that land was for the taking, thus misunderstanding Native use of lands. Father de Montigny, for example, proposed to “obtain some concessions within each mission, or two or three leagues of land” to help expand work.[49] But the Seminary priest did not make a reciprocal proposal. He instead seemed to suggest that he would take land, an effort that “could quickly threaten a Native community that relied on its terrain for farming, hunting, and sacred ceremonies.” No matter the scenario, if a reciprocal offer was not made, land could not be taken. Even though they did not “own” land, Native peoples “defended passionately the connections between land and identity that emerged through centuries of living with the land, an association that contained an essential spiritual element.”[50]

Land was simply “hands off,” a point made all too clear among the Natchez in 1729 when the French colonial commandant, Sieur de Chépart “spotted a prized patch of land in the center of the Natchez village that he wished to take for himself. The Natchez protested, telling Chépart that the ‘bones of their ancestors were held there in their temple.’ But Chépart made threats and promised ‘to set fire to the temple’ if they did not give him this land.” After a decision amongst themselves, “the Natchez seemingly conceded but needed ‘two moons longer . . . to prepare their new home.’ This time was granted but with further penalty that they ‘pay a large sum in poultry, grain, and pots of oil, as well as pelts to serve as interest for the delay that he was allowing them.’” Though the Natchez seemed to have accepted Chépart’s demands, they actually “quietly and carefully planned an assault on Chépart and the French for their disrespect. The morning of November 28, 1729, they began their attack. By the end of the day, some 230 French lives were lost and dozens more enslaved.”[51]

As summed up by Lieutenant Jean-François-Benjamin Dumont de Montigny: “Never had the lands of Indians been so brazenly confiscated. Up until then, if one had built on the Indians’ lands, either the Indians themselves had granted the land so as to gain the friendship and protection of the French for themselves and their habitations [as a reciprocal gesture], or else those who had settled on the Indian lands had paid them in advance with trade goods.”[52] The Natchez “were the dominant people casting out the disrespectful newcomers who would not play by Natchez rules.”[53]

Deception for Gain

Native peoples and Frenchmen both creatively expressed and differently interpreted strategies that, at times, entailed a level of deception. Father Marquette, for example, recognized that sometimes Native communities communicated danger that awaited a visiting party if they ventured beyond the host village. For example, during Marquette’s brief time among the Folles Avoines in the upper great lakes, he told them of his desire “to go and discover Those Remote nations, in order to Teach them the Mysteries of Our Holy Religion.” Surprised at his desires to move on, they “did their best to dissuade me.” They warned Marquette of Native communities that “never show mercy to Strangers, but Break Their heads with out any cause; and that war was kindled Between Various peoples who dwelt upon our Route, which Exposed us to the further manifest danger of being killed by the bands of Warriors who are ever in the Field.” The Folles Avoines further commented that “the great River was very dangerous, when one does not know the difficult Places that it was full of horrible monsters, which; devoured men and Canoes Together; that there was even a demon, who was heard from a great distance, who barred the way, and swallowed up all who ventured to approach him; Finally that the Heat was so excessive In those countries that it would Inevitably Cause Our death.” Marquette listened but ultimately dismissed their warnings “because the salvation of souls was at stake, for which I would be delighted to give my life; that I scoffed at the alleged demon; that we would easily defend ourselves against those marine monsters; and, moreover, that We would be on our guard to avoid the other dangers with which they threatened us. After making them pray to God, and giving them some Instruction, I separated from them.”[54]

There were always certain dangers no matter where one journeyed, but once Marquette arrived among the Quapaws, they too encouraged him not to go further south, that “we exposed ourselves to great dangers by going farther, on account of the continual forays of their enemies along the river, because, as they had guns and were very warlike, we could not without manifest danger proceed down the river, which they constantly occupy.”[55] This time Marquette listened. He and Jolliet had gathered a great deal of information and did not want to risk losing it by traveling into unknown territory further south. Consequently, the Frenchmen returned to Québec.

Whether it was the Folles Avoines, the Quapaws, or even Stadaconna and his people in interaction with Cartier, Native peoples voiced concerns of danger ahead in an attempt to keep Frenchmen among them, to keep their strength in arms, their goods, their alliances and relationships. They did not want to share their new-found friendships with another Native nation. Voicing concerns of danger further along their journey was one way to keep the Frenchmen from continuing on, though this strategy rarely worked.

Other forms of deception certainly emerged between Native peoples and the French. The Osages, for example, may have deceived the French both to maintain access to trade goods, and to maintain friendship despite the fact that their young warriors often attacked and killed French voyagers they encountered. Here is one such situation.

“In the fall of 1749, the Little Osages, one of the two Osage divisions, killed a Frenchman named Giguiere and his slave. Knowing that French officials would be angry, Little Osage leaders presented a scalp to Missouri Commandant Louis Robineau de Portneuf, saying that they had executed the murderer. Portneuf and his superiors accepted the scalp and declared their satisfaction. Yet soon Missouri Indians reported that the scalp did not belong to the guilty man, but to his brother. So the Little Osages bound ‘the real murderer,’ as they said, and delivered him to the French. Although a Missouri chief who was present said that he did not know whether this was the guilty man either, French officials accepted the Osages’ claim (again) that this was the guilty man. The governor of New France, Pierre Jacques de Taffanel, Marquis de La Jonquière, even praised the Little Osages’ ‘submission’ and ‘honesty.’ French officials decided that it was best not to quibble over the determination of guilt. At the same time, the Osages made concessions to French conceptions of justice by at least pretending to punish individuals, even if they were not necessarily the guilty parties.”[56]

Alternatively, Jean-Baptiste Bénard de La Harpe experienced a much less deceptive, yet rather frank exchange between himself and the Quapaws. A Tawakoni chief had told the Frenchman that there was “some yellow metal” further up the Arkansas River. Almost certainly, “these peoples knew about Europeans—their desire for Indian alliances, the goods they brought, and the products they wanted—and they knew what to say to persuade them to return.”[57] But when de la Harpe tried to reach the Tawakoni in 1722 by going up the Arkansas River, the Quapaws attempted to dissuade de la Harpe from moving towards this village. De la Harpe asked the Quapaws for information about ascending the Arkansas, but they refused to offer him any advice. They were “’unhappy with his expedition’ and feared that he ‘might make alliances with rival nations.’” As they often did when they did not want Frenchmen to journey onward, they warned de La Harpe, with a great deal of truth, “that Osage Indians had attacked another French party that had tried to buy horses from the towns upstream. That party had left seven months earlier and had not been seen since.” Quapaw women and men wept bitterly, telling de la Harpe “that they were mourning for the certain death of [de] La Harpe and his men if they persisted in this folly.” But the Frenchman did not cease his ambition to go upriver, perhaps interpreting the Quapaws’ actions as an attempt to both disrupt and deceive him. Though he asked for canoes, the Quapaws declined to give him any. Furious that this great French ally refused to help, some of his men stole a dugout canoe and the party began to row upriver. Several Quapaw warriors caught up with the Frenchmen and declared “that they were ‘hungry for killing Frenchmen,’” ending de la Harpe’s quest for gold further west.[58] In this instance, these Frenchmen were convinced that the Quapaws were not French allies. In truth, the Quapaws were actually protecting the French and their interests.

The French also served up their own doses of deception. In one poignant example, a French official named Diron d’Artaguiette chose to take advantage of the Choctaw’s reliance upon dreams. Native peoples communicated with their spirit world through various ceremonies and rituals. As a conduit between one’s soul and that of their personal spirit, dreams, often interpreted by tribal elders to help one understand their significance, were vital to a Native person’s spiritual life and served to validate one’s spiritual condition. Those spirits or manitous present within dreams were meant to guide the dreamer going forward. In sharp contrast, the French did not pay attention to dreams, particularly since Catholic tradition did not support such communicative ventures with the soul within its liturgy. Nonetheless, d’Artaguiette used a fake dream to subtly communicate his desires to the Choctaws to try and keep them from interacting and trading directly with the English. During a grand council in a Choctaw village, D’Artaguiette told them of a dream that he stated he had dreamt, though in reality he had only invented, and “informed the stunned Choctaw chiefs and notables that the shades of their ancestors had appeared to him in a dream and warned of impending disaster for the Choctaws if they did not hold fast to their true friends the French.” The Choctaws mustered a response, “declaring their intention to make war on the Chickasaws.” They then “asked Diron to lead them into battle,” but the Frenchman declined stating “he had no authority to do this and gave them over to Le Sueur. He was not, he reported later, sanguine [or hopeful] for the expedition’s success,” thus his quick willingness to pass the task to someone else.[59] No matter his optimism or lack thereof, Diron used an emboldened false dream to mislead or deceive the Choctaws, knowing their adherence to such words from the soul would turn them in his favor.

Misinterpretation of Disease

Some Native peoples interpreted the French, in particular the missionaries, as purposeful deliverers of disease meant “to ravage native populations and traditional medicine,” this through “the missionaries’ pictures, rituals, and gadgetry.” Native peoples blamed “the statues, the clocks, the windsock, the consecrated bread in the tabernacle, holy water, and even the Jesuits’ posture at prayer” as the harbingers of illness in their villages.[60] There were myriad accusations of sorcery against missionaries during epidemics that led Native peoples to identify any number of French items as tools of sorcery: writings, baptismal water, the cross, pictures, kettles, genuflection, black clothing. In some Native villages, nothing a Jesuit missionary carried into a village was above suspicion. Indeed Native individuals imagined “that everything which came in any way from us was capable of communicating the disease to them.”[61] Native peoples at times even interpreted Christianity as a kind of questionable medicine itself. During an epidemic in an Illinois village, the Peoria chiefs criticized the worth of Gravier’s Christian medicine: “After speaking of our medicines and of what our grandfathers and ancestors have taught us, has this man who has come from afar better medicines than we have, to make us adopt his customs? His fables are good only in his own country, we have ours, which do not make us die as his do.”[62] Even as a part of the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701, many Native peoples believed that the French gathered them together to destroy them with European disease. In truth, the event sadly coincided with an epidemic. Some Native peoples died before they arrived in Montreal. Still others died while there. Chief Kondiaronk of the Huron-Petun remarked: “‘Our father, you see us near your mat; it is not without having endured many dangers on such a long voyage. The falls, the rapids, and a thousand other obstacles did not seem so difficult for us to surmount because of the desire we had to see you and to gather together here. We found many of our brothers dead along the river [because of] sickness…However, we made a bridge of all those bodies, on which we walked with determination…You must judge from that how much we have been tested.’”[63] The Chief used the untimely and unfortunate deaths metaphorically as a bridge, something to support them and further them into their quest for peace, despite the belief that the gathering was deadly. Ironically, Chief Kondiaronk died of illness on August 3, 1701 during the peace conference.

Conclusion

Misunderstandings abounded throughout the thousands of interactions that occurred between Europeans and Native peoples. They began once the first Europeans landed on Native soil and lingered for decades if not centuries. Indeed, the first European invader, Christopher Columbus wildly chose to hear what he wanted to hear when he first encountered Native people on Guanahaní Island. He believed they “asked us if we had come from heaven.” Based on the sign talk from those who lived on the Great Inagua Island, he was convinced that “the people of the place gather gold on the shore at night with candles, and afterwards…with a mallet they make bars of it.” He became so convinced of his presumed understanding of the people that he creatively decided that the Grand Khan of China was right around the corner. With a presumed connection to East Asia, Columbus was convinced that he “soon could communicate more readily with regional people, particularly since he had a ‘Hebrew-Chaldee-Arabic-speaking interpreter, Luis de Torres,’ with him.”[64] But like those early Jesuits among the Illinois, Columbus never established an intimate relationship with the peoples, never developed proficiency with their language, and himself determined that he did not understand them at all, despite believing early on that they “soon understood us, and we them, either by speech or signs.”[65] Needless to say, he was crestfallen: “the people of these lands do not understand me, nor do I or anyone I have with me understand them.” As he himself concluded, “I often misunderstand, taking one thing for the contrary, and I have no great confidence.”[66] Likely, Native peoples felt much the same.

EXERCISES

Answer the following questions upon a bit of reflection.

- The Seminary priest, Father Saint-Cosme, served among the Natchez nation but was certain that “one had to make these barbarians men before making them Christians.”[67] Saint-Cosme was particularly vexed by what he called “thievery” among the Natchez and sought solutions to “fight back” and prevent them from gaining access to his goods. Saint-Cosme hoarded goods (personal and Christian alike) within his cabin to protect them and ensure their availability for his various Christian services.[68] Think about it: Why were the Natchez attracted to these goods? Why did they attempt to take them from the missionary? Why do you suppose the surly missionary felt these individuals were not men? What was misunderstood in these different observations?

- For three years, the Spanish did not fly their country’s flag among the Quapaws. This was unlike the French who had regularly kept the French flag raised at the fortress during their time among the Arkansas peoples. What might have been interpreted or misinterpreted by the Quapaws when it came to a lack of Spanish symbolism at the Arkansas fortress?

- The gift was the “word”. However, when Marquette and Jolliet met the Illinois, they were so overwhelmed with gifts that they chose “not to burden ourselves with them.” What might this have conveyed to the Illinois? How might they have responded? How did this highlight the Frenchmen’s misunderstanding of Illinois culture?

- White, Middle Ground, x. ↵

- Robert M. Morrissey, “'I Speak it Well': Language, Cultural Understanding, and the End of a Missionary Middle Ground in Illinois Country," Early American Studies 9, no. 3 (Fall 2011): 620. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 619. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 2. ↵

- Morrissey, “I Speak It Well,” 617-19. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 625, FN 17. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 625-26, FNs 18 & 19. ↵

- Morrissey, “I Speak it Well,” 627-628, 633. ↵

- Morrissey, "Speak it Well," 625, FN 17. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 111-12; Morrissey, “Speak It Well,” 640-41. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 641, FN's 61 & 62. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 619. ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 644, FN 76 . ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 621; White, Middle Ground, x. ↵

- “de Montigny,” Archives de l'Archdiocèse de Québec [hereinafter AAQ], W1, Eglise du Canada, vol. IV, 29; “de Montigny,” ANF, Série K 1374, no. 84, pp. 2–3; “de la Source,” ANF, Série K 1374, no. 85, p. 2. ↵

- “Saint-Cosme,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 26, pp. 7–9. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 82. ↵

- Leavelle, Catholic Calumet, 141. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 168. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 81-83 ↵

- Laudonnière, Three Voyages, 18. ↵

- James P. Baxter, A Memoir of Jacques Cartier, Sieur de Limoilou (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1906), 112-113. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 24; Biggar, Voyages, 65, 67. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 103. ↵

- Key, “Calumet and Cross,” 157. ↵

- W. David Baird, The Quapaw Indians: A History of the Downstream People (Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1980), 23; Margry, Découvertes, 2:190–193, 207, 212. Jones, Shattered Cross, 142. ↵

- Key, "Calumet and Cross," 160. ↵

- Key, "Calumet and Cross," 163. ↵

- Key, “Calumet and Cross,” 153. ↵

- Key, "Calumet and Cross," 160-61. ↵

- "Laudonnière, Three Voyages, 61. ↵

- Baird, Quapaw Indians, 17; DuVal, Native Ground, 24–26; Willard Hughes Rollings, Unaffected by the Gospel: Osage Resistance to the Christian Invasion, 1673–1906: A Cultural Victory (Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 2004), 16; Jones, Shattered Cross, 142. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 104. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 104-105; White, Middle Ground, 25; Thwaites, "Gravier's Voyage, 1700," JRAD, vol. 65, 119–121; “Marc Bergier to Louis Tiberge,” April 15, 1701, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 45, p. 8; “Marc Bergier to unknown,” April 15, 1701, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 46, p. 3. ↵

- Thwaites, "Gravier's Voyage, 1700," JRAD, vol. 65, 119. ↵

- Thwaites, "Gravier's Voyage, 1700," JRAD, vol. 65, 121-123. ↵

- Thwaites, "Gravier's Voyage, 1700," JRAD, vol. 65, 121-123. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 143-44. ↵

- DuVal, “Good Relationship,” 76-77; Thwaites, "du Poisson to Patouillet," JRAD, vol. 67, 255-59 ↵

- Key, "Calumet and Cross," 159; Sabo, "Inconsistent Kin," 123. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 188-89; “Bergier,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 50, pp. 15-17. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 189; “Bergier,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 50, pp. 15–17. ↵

- “Marc Bergier to unknown,” June 12, 1704, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 65, pp. 2–4. ↵

- White, Middle Ground, 98. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 153; White, Middle Ground, 99; Milo Quaife, ed., The Western Country in the Seventeenth Century: The Memoirs of Lamothe Cadillac and Pierre Liette (Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1917), 21. ↵

- “Marc Bergier to unknown,” June 12, 1704, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 65, pp. 2–4. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 197; White, Middle Ground, 101; Emma Helen Blair, ed., The Indian Tribes of the Upper Mississippi and Region of the Great Lakes, vol. 1 (Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark, 1911–1912), 302–303. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 123; Butler, Journal, 47. ↵

- “Lettre,” ASQ, Missions, no. 41a, p. 3. ↵

- DuVal, Native Ground, 7; Jones, Shattered Cross, 123; Leavelle, Catholic Calumet, 49. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 123-24; DuVal, Native Ground, 95. ↵

- Jean-François-Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, The Memoir of Lieutenant Dumont, 1715– 1747, ed. Gordon M. Sayre and Carla Zecher (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2012), 227–28. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 124; DuVal, Native Ground, 95. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 95 & 97. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 155. ↵

- DuVal, “Good Relationship,” 83-84; Jean Baptiste Benoist, Sieur de St. Claire, to Charles de Raymond, February 11, 1750, in Theodore Calvin Pease and Ernestine Jenison, eds. and trans., Illinois on the Eve of the Seven Years War 1747-1755 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1940), 165; Fabry de la Bruyère, "Extrait des lettres," 1742, 6:474; Pierre Jacques de Taffanel, Marquis de Lajonquière, to Antoine Louis Rouillé, Comte de Jouy, October 15,1750, Illinois on the Eve, 241; Pierre Jacques de Taffanel, Marquis de La Jonquière, to Antoine Louis Rouillé, Comte de Jouy, September 25,1751, Illinois on the Eve, 356-57. ↵

- Jean-Baptiste Bénard de La Harpe, "Relation du Voyage de Bénard de la Harpe, découverte faite par lui de plusieurs nations situées à l'ouest" Découvertes et Etablissements, 6:289-93, DuVal, “Good Relationship,” 86. ↵

- DuVal, “Good Relationship,” 86-87; Jean-Baptiste Bénard de La Harpe, The Historical Journal of the Establishment of the French in Louisiana, trans. Joan Cain and Virginia Koenig, ed. Glenn R. Conrad (Lafayette: University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1971), 202-4, 208-9; Jean-Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe, "Exploration of the Arkansas River by Benard de la Harpe, 1721-1722: Extracts from His Journal and Instructions," ed. and trans. Ralph A Smith, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 10 (Winter 1951): 348-51, 360. ↵

- Foret, “War or Peace,” 285; Diron to Maurepas, September 1, 1734. ANOM, AC, C 13a, 19:127vo-130vo Maurepas, September 22, 1734. ANOM, AC, C 13a, 19:138-139. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 109. ↵

- Peter Wogan, “Perceptions of European Literacy in Early Contact Situations,” Ethnohistory 41, no. 3 (Summer 1994): 416; Thwaites, "Le Jeune's Relation, 1638," JRAD, (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1898) vol. 15, 21; The Jesuit, Father le Mercier noted that through one work of European art, some Native individuals “persuaded themselves that this multitude of men [the damned], desperate and heaped one upon the other, were all those we [the Jesuits] had caused to die during the Winter; that these flames represented the heats of this pestilential fever, and these dragons and serpents, the venomous beasts that we had made use of in order to poison them." ↵

- Morrissey, “Speak it Well,” 643; Gravier, Kaskaskia Illinois-to-French Dictionary [Hereinafter KFD] (St. Louis: C. Masthay, 2002), 242; Thwaites, "Gravier--Illinois Mission," JRAD 64:173. ↵

- Havard, Montreal, 1701, 38. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 23; The Journal of Christopher Columbus, Cecil Jane, ed. L.A. Vigneras (New York, 1960), 27, 50, 51, 57. ↵

- Christopher Columbus, 196. ↵

- Christopher Columbus, 76. ↵

- “Saint-Cosme,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 37, p. 2. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 167-68. ↵