4 Ceremony, Ritual and Oratory

All cultures have ceremonies and rituals of importance to them. Americans celebrate Thanksgiving with feasts, football and family. Many Christian churches worldwide celebrate Shrove Tuesday or Mardi Gras the night before beginning 40 days of Lent. For that matter, public speaking and oratory play a part in ceremony and ritual. Presidents of the United States speak at their inauguration; and honorary degree recipients give commencement speeches. Thus, what cultural ceremonies are you familiar with? What takes place within them? What is communicated and to whom? Reflect on your experiences with ceremony, ritual, and oratory as you read this chapter.

Ceremonial exchange proved vital throughout the Mississippi River Valley. Native peoples communicated with their spirit world and with those who arrived among them through ceremony, ritual and oratory. Consequently, having been in North America since the early 17th century, many French knew well the importance of a Native nation’s ceremonial exchange. Though the French were different and strange, they were often welcomed as newcomers. As they entered the Pays d’en Haut and the Mississippi Valley, the French understood that trade items were “words”–utterances of peace, alliance, friendship–and that ceremony was vital in any form of diplomacy. Ceremony communicated hospitality, welcome, friendship, kinship, adoption, alliance. Ritual “words” mattered greatly. Even without a common language, a level of understanding through ceremony and exchange developed between the French and many Native cultures.

Father Jacques Marquette, his companion Louis Jolliet, and the Illinois nation shared the first recorded Native/French ceremonial exchange and oration within the upper Mississippi River Valley. These Frenchmen had just arrived among the Illinois. The latter took to council to discuss their presence among them so as to determine their next stage of interaction with these unknown, strangely dressed men:

“The Council was followed by a great feast, Consisting of four dishes, which had to be partaken of in accordance with all their fashions. The first course was a great wooden platter full of sagamité,–that is to say, meal of Indian corn boiled in water, and seasoned with fat. The Master of Ceremonies filled a Spoon with sagamité three or 4 times, and put it to my mouth As if I were a little Child. He did the same to Monsieur Jollyet. As a second course, he caused a second platter to be brought, on which were three fish. He took some pieces of them, removed the bones there from, and, after blowing upon them to cool Them, he put them in our mouths As one would give food to a bird. For the third course, they brought a large dog, that had just been killed; but, when they learned that we did not eat this meat, they removed it from before us. Finally, the 4th course was a piece of wild ox, The fattest morsels of which were placed in our mouths. After this feast, we had to go to visit the whole village, which Consists of fully 300 Cabins. While we walked through the Streets, an orator Continually harangued to oblige all the people to come to see us without Annoying us. Everywhere we were presented with Belts, garters, and other articles made of the hair of bears and cattle, dyed red, Yellow, and gray. These are all the rarities they possess. As they are of no great value, we did not burden ourselves with Them.”[1]

The latter comment, of course, appears short-sighted and dangerous for Marquette particularly because gifts among Native peoples held tremendous value and symbolically “spoke” great words of peace, invitation and acceptance. One can only imagine how such gifts might have been left behind without causing harm, or just what rejection of these goods may have communicated. Nonetheless, once guests were initially ceremoniously fed, and introduced to the community, such hospitality eventually evolved into the great Calumet Ceremony or Dance, one that the Illinois, the Quapaws and other Native communities celebrated along the Mississippi. As Marquette described it, the calumet dance “is performed solely for important reasons; sometimes to strengthen peace, or to unite themselves for some great war; at other times, for public rejoicing. Sometimes they thus do honor to a Nation who are invited to be present; sometimes it is danced at the reception of some important personage, as if they wished to give him the diversion of a Ball or a Comedy. In Winter, the ceremony takes place in a Cabin; in Summer, in the open fields.” Marquette described the care the Illinois took to prepare the ceremonial grounds. The center was

“completely surrounded by trees, so that all may sit in the shade afforded by their leaves, in order to be protected from the heat of the Sun. A large mat of rushes, painted in various colors, is spread in the middle of the place, and serves as a carpet upon which to place with honor the God of the person who gives the Dance; for each has his own god, which they call their Manitou. This is a serpent, a bird, or other similar thing, of which they have dreamed while sleeping, and in which they place all their confidence for the success of their war, their fishing, and their hunting. Near this Manitou, and at its right, is placed the Calumet in honor of which the feast is given; and all around it a sort of trophy is made, and the weapons used by the warriors of those Nations are spread, namely: clubs, war-hatchets, bows, quivers, and arrows.”

Ultimately, the calumet ceremony visually and ritualistically communicated a nation’s spirituality, culture, war prowess and the like. But this was just the beginning for

“those who have been appointed to sing take the most honorable place under the branches; these are the men and women who are gifted with the best voices, and who sing together in perfect harmony. Afterward, all come to take their seats in a circle under the branches but each one, on arriving, must salute the Manitou. This he does by inhaling the smoke, and blowing it from his mouth upon the Manitou, as if he were offering to it incense. Everyone, at the outset, takes the Calumet in a respectful manner, and supporting it with both hands, causes it to dance in cadence, keeping good time with the air of the songs. He makes it execute many differing figures; sometimes he shows it to the whole assembly, turning himself from one side to the other. After that, he who is to begin the Dance appears in the middle of the assembly, and at once continues this. Sometimes he offers it to the sun, as if he wished the latter to smoke it; sometimes he inclines it toward the earth; again, he makes it spread its wings, as if about to fly; at other times, he puts it near the mouths of those present, that they may smoke. The whole is done in cadence; and this is, as it were, the first Scene of the Ballet.”

The balance of the ceremony, thus a reflection of their society, continuously flows through the contrasting points of male/female, to and fro, inhale/exhale, earth/sky and the like. As a staged combat begins,

“the Dancer makes a sign to some warrior to come to take the arms which lie upon the mat, and invites him to fight to the sound of the drums. The latter approaches, takes up the bow and arrows, and the war-hatchet, and begins the duel with the other, whose sole defense is the Calumet. This spectacle is very pleasing, especially as all is done in cadence; for one attacks, the other defends himself; one strikes blows, the other parries them; one takes to flight, the other pursues; and then he who was fleeing faces about, and causes his adversary to flee. This is done so well with slow and measured steps, and to the rhythmic sound of the voices and drums that it might pass for a very fine opening of a Ballet in France.”

Finally, the ceremony moves into oratory as a warrior

“recounts the battles at which he has been present, the victories that he has won, the names of the Nations, the places, and the Captives whom he has made. And, to reward him, he who presides at the Dance makes him a present of a fine robe of Beaver-skins, or some other article. Then, having received it, he hands the Calumet to another, the latter to a third, and so on with all the others, until everyone has done his duty; then the President presents the Calumet itself to the Nation that has been invited to the Ceremony, as a token of the everlasting peace that is to exist between the two peoples.”[2]

The Illinois Calumet ceremony continuously communicated sacred elements of their culture–the power of the Calumet, one’s exploits in war, desires for peace, thanksgivings for the sun and the earth. These vital ceremonial components–communicated with sacred spirits–helped to maintain balance and order, one’s relationship within the community, with one’s manitou and with their overarching god.

Much like the Illinois, the Quapaws also invited the French and other Indigenous strangers “to engage in reciprocal actions with the entire nation,” to share in the celebration of the Calumet, “to participate in gift exchanges so as to forge and nurture an alliance, a kinship.”[3] While many Frenchmen believed this ceremony “created bonds of friendship that allowed for secure passage, trade relations and defensive support between the two groups,” for the Quapaws, this same ceremony helped to secure “balance, order and unity” within their community “according to a principle of complementary opposition in which separate but equal descent lines were linked by the rule of reciprocity.” Ultimately, the Calumet ceremony “extend[ed] this principle to relations with outsiders through the creation of ‘fictive’ or ancillary kinship relations.”[4] As such, when the French participated in the Calumet ceremony, they spiritually evolved into fictive kin who entered “a superintending familial and fiduciary environment, where the duties of kinship, and the wants, needs, and deserts of the parties measured the obligations that each party owed.”[5] The Calumet ceremony communicated a “framework for peace, alliance, exchange, and free movement” that served the Quapaws as well as the French. But it also provided the balance needed in first encounters to strengthen the emerging relationship. Once peace was established and fictive kinships recognized, both respective cultures became responsible for maintaining the established relationship.[6]

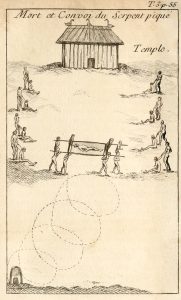

A part of ceremony and ritual included the purposeful placement of individuals to communicate their social status. Among the Natchez, the temple mound supported the Grand Soleil, the leader of the Natchez people. His hut, along with that of his sister who played a prominent role in the expansion of the great sun’s lineage, were both elevated above the remainder of the community within the Grand Village, thereby signaling their status as leaders of their hierarchical culture. Among the Illinois, when they prepared for war, leaders of campaigns were “distinguished from the warriors by wearing red Scarfs,” each made from the hair of bears and buffalo. They also painted their faces with red ocher found in great quantities some days journey from their village.[7] The Quapaws also expressed their social makeup through the placement of individuals, “having around us the elders, who were nearest to us; after them, the warriors; and, finally, all the common people in a crowd.”[8]

A unique element of the Quapaw Calumet ceremony focused on heroic stories that were publicly shared with those gathered. In 1682, Nicolas de la Salle described it as follows: “They brought out two Calumets with feathers of all colors and the red bowls of the pipes filled with tobacco. One gave them to the Chiefs who were in the middle of the plaza. These Chiefs and warriors have gourds filled with pebbles along with two drums.” With skin covered instruments, “the first ones began a song that they accompanied with a peal of their gourd rattles. Those having finished, others began the same thing, then those who had accomplished heroic actions used a club to strike a post erected in the middle of the plaza.…If anyone who struck the pole lied, the one who knew it would go to the pole with a skin to clean it off and to say that he had lied.”[9] Striking the pole communicated prowess, courage and the like. Lying was publicly called out and corrected. Once an individual wiped the pole clean, balance returned and the ceremony continued.

Everything was well choreographed and nonverbally communicated to the guests there present. These festivities obligated the “stranger” to reciprocate, to smoke the Calumet, to strike the pole and speak of his successes in battle to affirm alliance and kinship with the Quapaws.[10] Participation communicated good will–a willingness to participate in the sacred ceremonial world of the community. But balance was so vital to the Quapaw lifeway system that they even welcomed the celebration of the French Catholic ceremony led by LaSalle’s priest so as to provide their guests an opportunity to share their spirituality in kind: “They prayed, sang hymns, performed a ritual circle dance-marching around the village plaza three times and, according to expedition member Father Zenobius Membré, raised a cross and a column bearing the cross and the arms of France. Once the French had finished their ceremony, the Quapaws reciprocated, dancing, pressing their hands to the column and cross, and rubbing their bodies in much the same way they had greeted their guests.”[11]

At times, the balance and order of the Calumet ceremony came under threat. As Joutel and Cavelier journeyed east from LaSalle’s failed colony and assassination in the Texas region, they found themselves guests of the Quapaws who performed a Calumet ceremony for them. While they “sang with full throat,” Monsieur Cavelier, Joutel’s companion and brother to LaSalle, grew “tired of hearing them sing out and to be exposed to the heat of the sun, even though they had placed several skins in front.” But Cavelier knew that participation communicated good will and asked if his nephew could stand in for him. “They said that this was fine, and they continued to sing until the next day. Some were almost unable to speak, they were so hoarse.”[12] Years later, Father Saint-Cosme participated in a similar Calumet ceremony. He too understood the importance of balance within the Quapaw ceremony but also found a way to excuse himself, knowing that “It is necessary [to participate] if one does not want to come across as having a bad heart or bad designs.” Consequently, Saint-Cosme “put our men in our place after a while and they had the pleasure of being rocked all night.”[13] Somehow, the Frenchman had learned that if one stepped away from the ceremony, “someone had to participate or the alliance would not stand,” good will would not be communicated.[14] Thus, substituting others in one’s place enunciated the desire to continue to develop an alliance and ensure that balance and order remained.

So often, many nations along the Mississippi welcomed strangers into their midst, the French included. As long as these strange Europeans communicated friendship and alliance or interacted in a manner that was useful and respectful, then all was well. If they did not, then peaceful communication might cease, suspicions might arise, threats of violence might be inadvertently communicated. Take Antoine de la Mothe de Cadillac, for example. While Governor of Louisiana in 1715, he made a trip up the Mississippi River that proved “disastrous” for many. As he journeyed northward, he insulted numerous nations along the river, “quarreled with them, accepted their gifts without giving anything in return and…refused their hospitality.” As Bienville wrote, “all the nations are talking about it with very great scorn to the shame of the French.”[15] Indeed, several weeks after making his journey north, word came to Mobile, the capitol of French Louisiana at that time, that four Canadians had been killed by the Natchez. As Bienville suggested, “when Cadillac had declined to smoke the Calumet of peace on passing through the Natchez country, the Indians had been insulted by the Great Chief of the French.” Cadillac’s senseless actions had been interpreted as “a gesture of war.” Thus, by 1716, having “largely alienated the colonists as well as the Indians,” Cadillac was removed from his post as Governor of Louisiana.[16]

Gift exchange was simply an important part of the Calumet ceremony. Gifts spoke with power, so much so that a “gift” was also called “the word,” wrote the Jesuit Father le Jeune, “in order to make clear that it is the present which speaks more forcibly than the lips.”[17] Gifts both established and strengthened friendship and kinship. Mutual obligation and reciprocity were a core part of such relationships. Within the Calumet ceremony, the Quapaws “would place pelts at the foot of the pole where guests would place a gift and then take the one left by the preceding individual.” And though Joutel and his men had few goods after their flight from Texas, they understood the need to maintain a reciprocal relationship with the Quapaws. Consequently, the French interpreter, Jean Couture, a resident at the Quapaw village, relayed Joutel’s request that the Quapaws “wait until our return [from France], when we would have more goods in our possession, and that we would then strike the pole.” Content with Joutel’s honesty, “the Quapaws took the Calumet, in which they placed some tobacco, and presented it to M Cavelier…I [Joutel] gave them some bits of tobacco from France, or rather the islands that I had, so as to honor their Calumet; they smoked it, then took the Calumet, put it in a deerskin pouch, with the items that held it, and came to present it to M. Cavelier with several otter skins and porcelain necklaces.”[18] Offering M. Cavelier the Calumet bundle further communicated peace, safety and trust. The Frenchmen’s promised return, with future offerings of gifts and participation in pole striking communicated their desire to remain reciprocally balanced and trustworthy.

While the Calumet ceremony communicated alliance, a segment of one Caddoan ceremony was far more complex and puzzling to Joutel and his companions, particularly Jean Cavelier, the Sulpician priest. One evening, “a company of elders, attended by some young men and women came to our cottage in a body, singing as loud as they could roar….When they had sung awhile, before our cottage, they enter’d it, still singing on, for about a quarter of an hour. After that, they took Monsieur Cavelier the priest, as being our chief, led him in solemn manner out of the cottage, supporting him under the arms.” Once the entourage reached the ceremonial grounds, “one of them laid a great handful of grass on his feet, two others brought fair water in an earthen dish, with which they wash’d his face, and then made him sit down on a skin, provided for that purpose.” As before, elders seated themselves to communicate status. Once in place, “the master of the ceremonies fix’d in the ground two little wooden forks, and having laid a stick across them, all being painted red, he placed on them a bullock’s hide, dryed, a goat’s skin over that, and then laid the pipe thereon.” At this point, “The song was begun again, the women mixing in the chorus, and the concert was heightened by great hollow calabashes or gourds, in which there were large gravel stones, to make a noise, the Indians striking on them by measure, to answer the tone of the choir; and the pleasantest of all was, that one of the Indians plac’d himself behind Monsieur Cavelier to hold him up, whilst at the same time he shook and dandled him from side to side, the motion answering to the music.” Soon enough, the ceremony became particularly uncomfortable for the Sulpician priest:

“The master of the ceremonies brought two maids, the one having in her hand a sort of collar, and the other an Otter’s skin, which they plac’d on the wooden forks above mentioned, at the ends of the pipe. Then he made them sit down, on each side of Monsieur Cavelier, in such a posture, that they looked upon the other, their legs extended and intermix’d, on which the same master of the ceremonies laid Monsieur Cavelier’s legs, in such manner, that they lay uppermost and across those of the two maids. Whilst this action was performing, one of the elders made fast a dy’d feather to the back part of Monsieur Cavelier’s head, tying it to his hair.”

The singing continued but “Monsieur Cavelier [having] grown weary of its tediousness, and asham’d to see himself in that posture between two maids, without knowing to what purpose,” signaled that he did not feel well. Immediately, Cavelier was returned to his hut and the ceremony continued throughout the evening without him. But come morning, he was once again brought into the ceremony: “The master of the ceremonies took the pipe, which he fill’d with tobacco, lighted it and offered it to Monsieur Cavelier, but drawing back and advancing six times before he gave it to him. Having at last put it into his hands, Monsieur Cavelier made as if he had smoked and return’d it to them. Then they made us all smoke around, and every one of them whiff’d in his turn, the music still continuing.”[19]

This incredible, sacred ceremony both spiritually and symbolically communicated significant elements of Caddoan tradition to the Frenchmen. But one element in particular caught the attention of Monsieur Cavelier. As Juliana Barr suggests, when Sieur Cavelier’s legs were placed across those of two young women, this communicated “the brokering of a union.” That is, “the ritual nature of the event before an audience involving the whole community seems to suggest that the ceremony represented his symbolic assimilation into the ranks of Caddo leadership.” Indeed, his transformation appeared confirmed the next day: “The village caddís gave him the pipe wrapped in a deerskin bag so that ‘he could go to all the tribes who were their allies with this token of peace and that we Frenchmen would be well received everywhere.’”[20] George Sabo further suggests that Cavelier was being consecrated as a leader through a rite of passage that “embodied ritual metaphors of separation (from a former social status), transition (during the course of proceedings), and incorporation (into the newly conferred status).” The use of ritual in this particular context “underscores the importance of elites within Caddoan cultural frameworks and their exclusive roles performed in undertaking important responsibilities on behalf of their communities.”[21]

Balance and Alternative Rituals

Balance within Native societies had to be maintained for the benefit of the community. Oftentimes this was communicated through ceremony and reciprocity but also emerged through various types of enacted rituals. In sixteenth century Florida, Ribault and Laudonnière chronicled a rather dramatic response to a supposed battle incident that took place between the French and enemies of the Native peoples with whom the French were in conversation. All had gathered in the Chief’s abode to celebrate the presumed victory of the French over the Thimogona, enemies to the Chief. A Frenchman named François la Caille, sergeant of the men, remarked (though a lie) that he had taken his sword and “had thrust through two Indians, who were running into the woods and that his companions had done no less on their part.”[22] Seemingly satisfied, the Chief invited the Frenchmen to enter his home. Once in the hut, he had Captain Vasseur “sit next to him in his own chair,” an honorable position to be sure. Once all were seated according to rank, “the Indians presented their drink of cassena to the chief and then to his closest friends and favorites.” Shortly thereafter, “the one who brought the cup set it aside and withdrew a little dagger which had been stuck in the roof of the house; and prancing around like a madman with head held high and with great steps, he rushed over to stab an Indian who sat alone in one of the corners of the building, at the same time crying out in a loud voice, ‘Hyou.’” The victim made no response but instead “quietly endured it.” The dagger returned to its original location, the man “began to serve the drink again.” But after only three or four persons, “he left his bowl again, took the dagger in his hand, and returned to the Indian he had struck before, giving him a very sharp blow on the side and crying out, ‘Hyou,’ as he had done before.” Once again, he returned the dagger to its place in the roof. Not long after:

“The man that had been struck fell down backwards, stretching out his arms and legs as if about to die. Then the younger son of the chief, dressed in a long white skin and weeping bitterly, placed himself at the feet of the man who had fallen backward. A half of a quarter of an hour afterward two others among his brothers, similarly dressed, came to the persecuted one and began to groan pitifully. Their mother came from another area bearing a little infant in her arms and going to the place where her sons were, uttered a series of moans and raised her eyes to the sky. She prostrated herself on the earth, crying so dolefully that her mournings would have moved the hardest heart in the world with pity. Yet this was not enough, for then a company of young girls came in, weeping grievously as they went to the place where the Indian had collapsed. Afterwards, as they picked him up, they made the saddest gestures they could devise and carried him away into another lodging a short distance from the hall of the chief. They continued their weeping and wailing for two long hours. Meanwhile, the Indians continued to drink the cassena, but in dead silence, so that not one word was heard in the room.”[23]

Though the Frenchmen did not initially understand what this dramatic presentation communicated, they eventually learned from the Chief that “this was simply a ceremony by which these Indians recall the memory of the accomplishments and deaths of their ancestor chiefs at the hands of their enemies, the Thimogona.” As such, each time one returned from the Thimogona without bringing prisoners or scalps (as the French had done), “he ordered as a perpetual memorial to all his ancestors that the best loved of all his children should be struck by the same weapon by which his ancestors had been killed. This was done to renew the wounds of their death so that they would be lamented afresh.”[24] Ultimately, this ceremony served to remember the deceased and to maintain the balance needed–between those who had died and those they mourned. As for the injured lad—they took him away to treat his wounds.

Other sacred ceremonies further communicated cultural demands that provoked curious responses from the French. Among the Taensas, for example, whenever a chief died, those who had served him on earth were sacrificed to serve him in the afterlife. Alarmed by this practice, Father François de Montigny put a stop to this sacrificial element during a chief’s funeral in 1700. Consequently, “while he believed he saved the lives of those not sacrificed, de Montigny’s disruption of their Native tradition impeded the society’s reverence of their chief as well as the balance within their spiritual world.”[25] Indeed, not too long after de Montigny’s disruptive actions, a horrific thunderstorm blew in and on the night of March 16-17, 1700 “lightning struck the Taensas’ temple, set it on fire, and burned it up.” The Taensas had to appease the angry spirit. Thus, “An old man, about sixty-five years old who played the role of a chief priest, took his stand close to the fire, shouting in a loud voice, ‘Women, bring your children and offer them to the Spirit as a sacrifice to appease him.’ Five of those women did so, bringing him their infants whom he seized and hurled into the middle of the flames. The act of those women was considered by the Indians as one of the noblest that could be performed.” A few days later, these same women, “clothed in a white robe made from mulberry bark, and [with] a big white feather [that] was put on the head of each,” sat before the Chief’s abode. “All day they showed themselves at the door of the chief’s hut, seated on cane mats, where many brought presents to them. Everybody in the village kept busy that day, surrounding the dead chief’s hut with a palisade of cane mats, reserving the hut to be used as a temple. In it, the fire was lighted, in keeping with their custom.”[26]

Spirituality among the Taensas and the neighboring Natchez comprised three significant realms—the lower, the upper, and the present realm. The lower realm included reptiles, fishes and legendary monsters. The upper realm included the sky, astronomical elements such as the sun, the moon and the stars, and thunder and lightning. The present or earthly realm held animals, plants, and humans. Only the Great Sun (the paramount chief) could transcend from the present realm into the others and maintain balance and unity within the cosmos. Thus, when a chief died, the sacrifice of his earthly servants allowed them to follow him into the afterlife to continue to serve him.[27] The destruction of their sacred temple by a lightning bolt, they believed, stemmed from an angry spirit who was “incensed because no one was put to death on the decease of the last Chief, and that it was necessary to appease him.”[28] Consequently, when the “five heroines” sacrificed their children to follow the chief into the afterlife, order and unity were returned to the Taensas’ spiritual realm. The infant sacrifice soothed the Taensas’ spirit. And despite de Montigny’s revulsion at what had transpired, he too found “a sense of order and unity” since the young sacrificed souls had “been recently baptized” and thus were in his own acknowledged spiritual domain–heaven.[29]

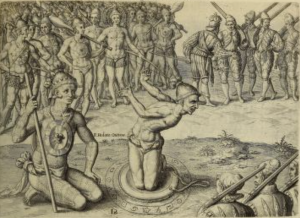

Ceremony also allowed one to communicate with the spiritual realm to seek guidance and protection against enemies. In this example from 16th century Florida, a warrior went to the riverbank, surrounded by ten chiefs, to ask the spirits for success in battle. He promptly asked that water be brought to him. Once it arrived, “he looked up to heaven and began to discuss many things by gestures, showing a great heat in his emotions and shaking his head, first one way and then another.” Then with a great wrath, “he turned his face toward the direction of his enemies to threaten them with death. He also looked toward the sun, praying for glorious victory over his enemies.” After a half hour, “he sprinkled water from his hands over the heads of the chiefs, water which he had taken from a vessel that he held. Furiously he threw the rest of the water on a fire which had been expressly made for this purpose. That done, he cried three times, ‘He, Thimogona,’ and was accompanied in this by more than five hundred Indians. They were all assembled there and cried out in unison, ‘He, Thimogona.’” Through this ceremony, the warrior Satouriona “begged the sun to give him victory and happiness so that he could scatter the blood of his enemies as he had scattered the water at his pleasure. Moreover it besought that the chiefs who were sprinkled with a part of the water might return with the heads of their enemies, which is the greatest and only measure of their victory.”[30]

Ceremony could also be used to ask questions, to forewarn of danger ahead, to keep individuals among one’s nation and away from interacting with others beyond their village. Cartier, for example, had long sought to go up the St. Lawrence River to the village of Hochelega at modern-day Montréal, but the Native peoples of Stadaconna opposed this. They exclaimed that it was too dangerous, but in reality may not have wanted the people of Hochelega to catch the attention of Cartier and his men. To try and convince Cartier not to go, Donnacona and his people, including the two young men taken to France by Cartier, staged an elaborate ceremony:

“They dressed up three men as devils, arraying them in black and white dog-skins, with horns as long as one’s arm and their faces coloured black as coal, and unknown to us put them into a canoe. They themselves then came towards our ships in a crowd as usual but remained some two hours in the wood without appearing, awaiting the moment when the tide would bring down the above-mentioned canoe. At that hour they all came out of the wood and showed themselves in front of our ships but without coming so near as they were in the habit of doing.”

One of the individuals previously taken to France, Taignoagny came forward to greet Cartier. “Soon after arrived the canoe in which were the three men dressed as devils, with long horns on their heads. And as they drew near, the one in the middle made a wonderful harangue, but they passed by our ships without once turning their faces towards us, and proceeded to head for the shore and to run their canoe on land.” Once there, Donnacona and his people siezed the canoe and the three devils fell down as if dead. The people “carried them, canoe and men, into the wood which was distant a stone’s throw from our ships, and not a soul remained in sight but all retired into the wood.” Not long after, “Taignoagny and Dom Agaya came out of the wood, walking in our direction, with their hands joined and their caps under their arms, pretending to be much astonished. And Taignoagny began to speak and repeated three times, ‘Jesus,’ ‘Jesus,’ ‘Jesus,’ lifting his eyes towards heaven. Then Dom Agaya called out ‘Jesus,’ ‘Maria,’ ‘Jacques Cartier,’ looking up to heaven as the others had done.” Alarmed by these gestures and cries, Cartier asked “what was the matter, and what new event had happened.” They answered that they had very bad news to share, saying that their god, Cudouagny, “had made an announcement at Hochelaga, and that the three above-mentioned men had come in his name to tell them the tidings, which were that there would be so much ice and snow that all would perish.” The Frenchmen immediately laughed and mocked them “saying that their god Cudouagny was a mere fool who did not know what he was saying; and that they should tell his messengers as much; and that Jesus would keep them safe from the cold if they would trust in him.” The two Natives then asked Cartier “if he had spoken to Jesus; and he replied that his priests had done so and that there would be fine weather.” They then thanked Cartier for this information, and went into the woods to communicate it to their people, who rushed out, gave three great shouts, and fell into dancing and singing as as if overjoyed with the news given. Though the level of tenseness may have declined, Donnacona declared that no one would accompany him to Hochelaga unless a hostage was left to ensure safe return. Cartier responded: “if they were not ready to go willingly, they could stay at home, and that on their account he would by no means give up his attempt to reach that place.”[31]

Personal Rituals

Although often large in scale, ritual and ceremony did not have to occur solely within the boundaries of a village, or in the central plaza. A single individual could conduct a smaller more personal ritual to communicate with his or her manitou, to ask for safety, to offer thanks, or even to work through a vision quest to learn which sacred manitou emerged as one’s own. For example, asking for protection on a journey. At an infamous point on the Mississippi, a rock line often proved dangerous to river travelers. In Native tradition, one could not pass this location without acknowledging its spirit. Marquette and Jolliet actually passed this place, “that is dreaded by the [Native peoples], because they believe that a manitou is there, that is to say, a demon, that devours travelers; and [those], who wished to divert us from our undertaking, warned us against it.” The “demon” itself was a “small cove, surrounded by rocks 20 feet high, into which The whole Current of the river rushes; and, being pushed back against the waters following It, and checked by an Island nearby, the Current is Compelled to pass through a narrow Channel. This is not done without a violent Struggle between all these waters, which force one another back, or without a great din, which inspires terror…”[32] There, Marquette and Jolliet may not have understood the importance of ritually and spiritually communicating with this rock, but the Native peoples certainly did. As Saint-Cosme described this same Mississippi gauntlet in 1698, individuals who passed through it “offered sacrifices to the rock to ensure safe passage.” This was certainly justifiable, a requisite ritual since just a few years earlier, some fourteen Miamis lost their lives at this dangerous Mississippi junction.[33]

But other important spiritual practices occurred “in the field.” As Joutel and his Quapaw guides hunted buffalo while journeying to the Illinois region, he witnessed their ritual over the fallen creature: “I noticed several gestures that tended towards superstition that they made over the buffalo before dressing it.” They did this “either because it was the first one we had killed since we began our journey together or, as I saw in the next stages, that they wanted to make some sort of sacrifice to it.” As they processed the buffalo, “they adorned his head with down from a swan and goose (died red)…then they put tobacco in his nostrils and in the hoofs of his feet. Next, after having skinned it, they pulled his tongue, from which they cut a small piece, that they put back in the mouth of the animal. After which, they cut several pieces of meat that they set aside. They planted two forked sticks with a cross piece, on which they hung the pieces of meat that were left here, as a sacrifice.” Aside from this thank offering to the buffalo, the Quapaws also offered “a sacrifice of tobacco and grilled meat that they placed on forked sticks and left on the bank for her [the Wabash River] to use as she saw fit.” The same was done at the mouth of the Missouri, “to which the Quapaws did not fail to offer a sacrifice.” Further along the journey, Joutel and his men even noticed that their guides “had certain days when they would fast, and we knew this, when on awakening they would rub their face, arms or another part of their body with icy soil or crushed charcoal. That day, they would not eat until 10 or 11 at night, washing themselves with water before eating…to have a good hunt and to kill buffalo.”[34]

In these diverse yet sacred events, the Quapaws communicated with their spirit world. They offered thanks for the fallen buffalo whose meat would sustain them. They participated in a ritual fast to ask for additional opportunities to obtain sustenance along their journey. They also offered gifts to the waterways so that they might pass without incident. Even at the controversial painted rock discussed in the previous chapter, the Quapaws offered a sacrifice to request safe passage as they journeyed northward. The spirits of animals, water and the Piasa had to be recognized and acknowledged to maintain balance with their spirit world so to ensure that their safe journey continued, and that sustenance could be found.

When ceremony broke down, relationship dissolved, balance failed, and communication ended between the Native peoples, strangers or even the spirit world. Such was the case for the Quapaws once the Americans moved into the Arkansas territory after 1803. The Quapaws had long used ritual to welcome Europeans into their world. Certainly the French had received the Calumet through the great Calumet ceremony which transformed them “from stranger to kin.”[35] The Spanish, to this researcher’s knowledge, did not participate in such a ceremony but came to understand the importance the Quapaws placed in European-styled ceremony. Unfortunately, Americans ignored the Quapaws, traded with local farmers rather than the Native community, established no system of reciprocity which was normally expected when strangers entered Quapaw territory, and thus refused any form of ceremony. Without reciprocity or ritual, the Americans communicated ill will and disinterest. Effective, meaningful communication failed between the two groups resulting in the removal of the Quapaws from their lands, first to the Caddo region in Northwest Louisiana and finally to Northeast Oklahoma where they reside today.

Council and Oratory

Council and oratory also served as important communicative traditions of Native peoples. These “formal and ritualized events” included both council discussions and public speaking with all participants expected to listen quietly and deeply. The strategy was simple: “to speak and listen, each party reminding the other of the benefits of a mutually respectful and advantageous relationship.”[36] Marquette benefited from this all too well. When he and Jolliet visited the Quapaws in 1673, some within the village thought “to break our heads and rob us,” wrote the Jesuit priest, but “the Chief put a stop to all these plots.” Within a secret council, the Quapaw elders addressed the aggression aimed at Marquette and his men. After thoughtful, careful deliberation, the Chief “danced the Calumet before us,” wrote Marquette, “as a token of our entire safety; and, to relieve us of all fear, he made me a present of [the Calumet].”[37] Ultimately, Quapaw strategies of council–discussion, listening, oratory and ceremony–reflected the extreme care they took when faced with important village decisions. Sharing the Calumet with the Frenchmen after council spoke words of trust, safety and balance. Marquette’s peaceful gestures were reciprocated in kind by the Quapaws.

Oratory had a distinct style, as noted by the Frenchman, Antoine-Simon le Page du Pratz who lived near the Natchez in the 1720s:

“Whenever Native peoples, whatever their number, conversed with each other, only one person spoke at a time; never did two persons talk simultaneously. Even if someone in the same gathering had something to say to another person, he did so in a low voice so that others could not hear anything…When a question was debated in council, one kept silent for a while; everyone spoke when it was his [or her] turn, and never cut off a person who was speaking. This custom could hardly keep Native peoples from laughing when they saw several French men and women conversing together, always speaking at the same time. It’s been about 2 years that I perceived and asked the reason [for this laughter] without a response. Finally, I pressed a friend on this point. He asked, ‘what does that matter to you? It doesn’t pertain to you.’ Finally I pressed my friend for an explanation. After begging me to not get angry with him, he replied in Mobilian Jargon: ‘Our people say that when several French are together, they all speak at the same time like a flock of geese.’”[38]

Years before this description, Henri Joutel experienced the Quapaw system of council and oratory as he sought support for his journey to the Illinois country. When the Frenchman asked for a canoe and men to help him travel northward to the Illinois country, “the chief and the elders heard this proposition via the interpreter…this Chief told us that he would go to the other villages of this same nation to let them know of our arrival and to deliberate with them what one must do…His oration finished, as well as several speeches from both sides, the Chief served us smoked meat, several styles of bread, watermelon, pumpkin and other similar items, depending upon their stores; after which, they presented us [with the Calumet] to smoke.” Ultimately, as he journeyed to each village, “the chiefs took some time to deliberate on Joutel’s offer. They took some time to think without speaking, after which they held a bit of a council between themselves and then agreed to what we asked of them. That is to say, one man from each village.”[39]

17th century French missionaries among the Mi’kmaq of Acadie–today known as Nova Scotia–remarked on the Mi’kmaqs particular style of oratory as well. Father Pierre Maillard noticed that “treating of solemn, or weighty matters,” used particular grammatical structures so to “terminate the verb and the noun by another inflexion, than what is used for trivial or common conversation.” For the Mi’kmaqs, “gesture, cadence, diction, tone, and specific grammatical constructions contributed to a formal oratorical performance.”[40] In the mid-18th century, Alexander Henry traveled among Ojibwes and remarked that the “Indian manner of speech is so extravagantly figurative, that it is only for a perfect master to follow it entirely.”[41] As the historian Harvey describes it, “Powerful Native groups established the terms for diplomacy, which was conducted in highly formal and ritualized modes of discourse that shaped listeners’ ideas of the languages’ sounds and cadence, beauty and gravitas, regardless of whether they understood the meaning of what was said.”[42] Even as late as the mid-19th century, the Cherokee author John Rollin Ridge wrote that “the speech of the North American warrior…is full of metaphor and the essence of poetry” and that “poetry stems from every noble sentiment of the human heart…and its sprit is constantly around us.”[43] And yet, some Frenchmen completely dismissed the significance of ceremony and oratory. Father François de Montigny was in the Taensas village in 1699 when the Natchez arrived to offer peace. While there, de Montigny witnessed “a reception like anyone would desire.” The Taensas took the Natchez to “the door of the temple,” where the chief, elders and other members of the village assembled together. The keeper of the temple, an elder, “addressed the spirits and those there gathered, ‘exhorting both nations to forget the past and to live in unalterable peace.’” But seemingly fatigued and uninterested by the events, de Montigny chose not to fully write about the several ceremonies and oratory that took place, events “that would take too long to describe.” Nonetheless, he did mention some of the presents given, including “six robes of muskrat, well worked,” but otherwise chose not to record the remainder of the oration and ritual.[44]

Those who served as orators trained for this particular role “in memory, elocution, performance, and the fictive kinship titles by which one nation referred to another in formal address.” So distinguished were some of these speech makers that the Jesuit priest Brebeuf believed them “to be born orators.” Indeed, some Native individuals were known for their wit in discourse. They were the chosen ones, well prepared to give orations. One such orator was Kondiaronk, a Huron-Petun Chief of Michilimackinac in the Pays d’en Haut who played a vital role in building the Montreal Peace Accord of 1701. Father Charlevoix wrote of him, that “’Nobody could ever have more wit than he’” as he shone “‘in private conversations, and people often took pleasure in teasing him just to hear his repartee, which was always lively and colourful, and usually impossible to answer. He was in that the only man in Canada who could match Count Frontenac, who often invited him to his table for the pleasure of his officers.’”[45]

Some of Kondiaronk’s many orations were filled with metaphors. During an event prior to the great peace, Kondiaronk remarked “’The sun today dissipated the clouds to reveal this beautiful Tree of Peace, which was already planted on the highest mountain of the Earth.’” As Havard describes it, “He was using the language common to Native diplomats, one laced with images, whether the subject was war (‘boil the kettle,’ ‘toss the hatchet to the sky,’ ‘stir the earth’), reconciliation (‘weep for the dead,’ ‘wrap the bones,’ ‘cover the dead’), or peace (‘hang up the hatchet,’ ‘tie the sun,’ ‘plant the Tree of Peace’).” Indeed, the Iroquois metaphor of the Tree of Peace played a prominent role among the many orators at the 1701 peace negotiations. This tree was “to be ‘planted’ or ‘raised’ on the ‘highest mountain of the Earth’ and provided with ‘deep roots so that it [could] never be uprooted.’ Its branches and foliage rose ‘to the heavens,’ providing ‘dense shade,’ so that ‘those who [sat] under it [were] …refreshed…sheltered from any storms that might threaten them,’ and able to ‘do good business.’” Aside from the tree metaphor, the hatchet too played a prominent role such that “’The hatchet is stopped, we have buried it during these days here in the deepest place in the earth, so that it will not be taken up again by one side or the other.’” Even a large bowl for sustenance such as a kettle conveyed “an agreement to share hunting territory and not to kill one another when they met (‘Let us eat from the same kettle when we meet during the hunt’; they would share the same ‘dish’ as ‘brothers’; ‘When we meet, we will look on each other as brothers, we will eat the same meal together’).”[46]

General preparation for the Peace of Montreal had its own ritual. Three ceremonies of condolence–“the wiping of tears, the clearing of the ears, and the opening of the throat”–served to prepare participants for the upcoming discussions of the peace accord, to clear their thoughts and prejudices, listen attentively and speak with great consideration of one’s words.[47] As individuals gave speeches, a cross-cultural use of terminology emerged, particularly on the part of the French. Governor Callière himself declared:

“I gather up again all your hatchets, and all your instruments of war, which I place with mine in a pit so deep that no one can take them back to disturb the tranquility that I have re-established among my children, and I recommend to you when you meet to treat each other as brothers, and make arrangements for the hunt together so that there will be no quarrels among you… I attach my words to the wampum belts I will give to each one of your nations in order that the elders may have them carried out by their young people. I invite you all to smoke this Calumet that I will be the first to smoke, and to eat meat and broth that I have had prepared for you so that, like a good father, I have the satisfaction of seeing all my children united.”[48]

The political organization of many Native nations influenced oratory that “was based neither on coercive power (the chiefs did not impose anything, they proposed) nor on majority rule, but on the rule of consensus.”[49] Nicolas Foucault, the first priest to live among the Quapaws in 1701 may have longed for support from the Quapaw leadership to help him persuade them to embrace Christianity. But if this Seminary priest sought backing from the village chief, he would have likely been quite disappointed since “the chief’s authority rested on his power of persuasion not coercion.” That is, the Quapaw leadership stood by a tradition of balance and equality without unilateral power. Chiefs were not micro managers; they could not coerce others. Manitous, on the other hand, held power: “Through visions, spiritual rituals, and reciprocal actions, these powerful spirits guided individuals throughout their lives.”[50] Even when Native peoples were confronted with orders from Onontio (Governor of Québec as he was called, or Great Mountain in Huron-Iroquois language), “they saw the power of the governor as being like that of their chiefs. His orders were interpreted not as inflexible commands, but as proposals to be debated; and his authority extended no further than his generosity.”[51]

Although the Quapaws could disagree with their chief, many a Frenchman wisely came to trust a Quapaw leader’s expertise. In 1781, the then French leader of what was Spanish Arkansas post, Balthazar de Villiers, encouraged chief Angaska “to take a party to the Chickasaws to dissuade them from involvement in these [regional] attacks.” But the chief respectfully declined de Villiers’ request. Angaska reassured the Frenchman that he “would never refuse him anything” but added that “in this case, an expedition against the Chickasaws would send the wrong message.” Angaska explained, “to be sending people so often to that nation would be an indication that [we] feared them, which is far from being the case.” De Villiers deferred to the chief’s judgement, telling his superior that “I quite agreed with him and did not mention it to him any more.” A few days later, Angaska returned to the post “and promised that, as soon as some of his men returned from Natchez, they would consider the possibility of an expedition.” In the end no attack took place.[52]

Conclusion

No matter their nation, Native peoples did not distinguish between diplomacy and trade. Among the Quapaws, for example, “the world was divided into friends and enemies, and friendly relations involved goods exchange. Friendship entailed reciprocal obligations, which included hospitality and presents. Sharing goods proved and sustained friendship between peoples.” Ultimately, anytime one arrived among the Quapaws, the Calumet was a central source of connection—the smoking of the Calumet between the Quapaws and the stranger as well as the partaking of food throughout an elaborate meal, both “clearly expressed friendship between alien peoples, an especially important function when language differences made speaking impossible or easily misunderstood.” The reciprocal actions of smoking the Calumet, consuming a meal, exchanging and distributing gifts and making decisions through consensus rather than chiefly rule highlighted the mutual obligations and collaborative, balanced interactions that sustained Quapaw society.[53] Thus, the alliances that emerged through ceremony, ritual and oratory, be they between strangers or with one’s spiritual manitou, cultivated any number of vitally important states of being such as peace, friendship, kinship, cooperation, collaboration, assurance, strength and trust. While words were often not understood, ritual could be comprehended to a point, particularly as it was consistently experienced by the French within the Mississippi River Valley. Though it was never easy to fully discern what either side intended at times, both sides attempted to communicate to the best of their ability with signs, gestures, words, ceremony. In many instances, one could understand the other for practical reasons, but more abstract reasoning faltered, particularly when it came to religion and spirituality that were shared from one culture to the other. We examine this concept later in this text.

Activities

Answer the following questions and/or complete the following exercises.

- The Jesuit priest Father Jacques Gravier interacted with several of the Quapaw villages in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Here is a description of one encounter at their Kappa Village in October of 1700. Read through this description and analyze the ceremony, salutation, and reciprocity given, and any other elements you see relevant to previous chapters.

“The 31st [of October]. We arrived, about 9 o clock in the morning, at the Village of the Kappa Akansea….de Montigny had [previously] erected a Cross on the Hill, which is very steep and 40 feet high. After saluting the Cross, and chanting the Vexilla Regis with the French, we gave notice to the Akansea by 3 Gunshots; and in less than ten minutes, at the most, two Young men appeared with Swords in their hands, closely followed by the Chief of the Kappa and that of the Tourima, and 20 or 30 well-formed young men with their Bows and arrows. Some had swords and 2 or 3 English guns, which had been given them by the person who, the year before, had brought a quantity of goods to them to alienate them from the french…However, the Chiefs invited me to go to their village, which consists of 40 Cabins. A number of the French accompanied me, while the others kept the Canoes at anchor. They took me to the Cabin of the Chief, who made me sit down on a mat of Canes adorned with figures, and at the same time they put on the fire the Kettle, containing green Indian corn seasoned with a large quantity of dried peaches. They brought me from another Cabin a large dish of Ripe fruit of the Piakimina, which is almost like the medlar of France. The dish was handed to the Chief to give to me. As it is the most delicious fruit that the savages have from the Illinois to the sea. The Chief did not fail to begin his feast with it. After tasting a little of it, I had the dish carried to brother Guibert and to the Frenchmen, who sat opposite me. I did the same with the Sagamité. I observed that all who entered the Cabin remained standing at the door, and advanced only when the Chief told them to do so and to sit down….I asked him [the Chief] whether he remembered having formerly seen in their village a frenchman, clad in black, and dressed as I was. He replied that he remembered it very well, but that it was so long ago that he could not count the years. I told him that it was more than 28 years ago. He also told me that they had danced to him the Captain’s Calumet—which I did not at first understand, for I thought that he spoke of the Calumet of the Illinois, which the Kaskaskia had given to Father Marquette to carry with Him in the Mississippi country, as a Safeguard; but I have found, in the Father’s journal, that they had indeed danced the Calumet to him. He afterward…asked me to remain until the following day, because he wished with his young men to sing the Chief’s Calumet for me. This is a very special honor, which is paid but seldom, and only to persons of distinction; so I thanked him for His good will, saying that I did not consider myself a Captain, and that I was about to leave at Once. My answer pleased the French, but was not very agreeable to all the others who, in Doing me that honor, hoped to gain presents from me. The Chief escorted me to the Water’s edge, accompanied by all his people; and they brought me a quantity of dried peaches, of Piachimina, and of Squashes. I Gave the Chief a present of a little lead and powder, a box of vermilion wherewith to daub his young men, and some other trifles, which greatly pleased him….After I had embarked, They fired four Gunshots, to which the people who were with me replied.”[54]

- Here is another form of initial interaction between Marquette, Jolliet and the Illinois. Read through it and describe each of the communicative elements you find within this text:

“We silently followed The narrow path, and, after walking About 2 leagues, We discovered a village on the bank of a river, and two others on a Hill distant about a half a league from the first. Then we Heartily commended ourselves to God, and, after imploring his aid, we went farther without being perceived, and approached so near that we could even hear the [Illinois] talking. We therefore Decided that it was time to reveal ourselves. This We did by Shouting with all Our energy, and stopped, without advancing any farther. On hearing the shout, the [Illinois] quickly issued from their Cabins, And having probably recognized us as Frenchmen, especially when they saw a black gown–or, at least, having no cause for distrust, as we were only two men, and had given them notice of our arrival,–they deputed four old men to come and speak to us. Two of these bore tobacco-pipes, finely ornamented and Adorned with various feathers. They walked slowly, and raised their pipes toward the sun, seemingly offering them to it to smoke,–without, however, saying a word. They spent a rather long time in covering the short distance between their village and us. Finally, when they had drawn near, they stopped to Consider us attentively. I was reassured when I observed these Ceremonies, which with them are performed only among friends; and much more so when I saw them Clad in Cloth, for I judged thereby that they were our allies. I therefore spoke to them first and asked them who they were. They replied that they were Illinois; and, as a token of peace, they offered us their pipes to smoke. They afterward invited us to enter their Village, where all the people impatiently awaited us….At the Door of the Cabin in which we were to be received was an old man, who awaited us in a rather surprising attitude, which constitutes a part of the Ceremonial that they observe when they receive Strangers. This man stood erect, and stark naked, with his hands extended and lifted toward the sun, As if he wished to protect himself from its rays, which nevertheless shone upon his face through his fingers. When we came near him, he paid us This Compliment: How beautiful the sun is, O frenchman, when thou comest to visit us! All our village awaits thee, and thou shalt enter all our Cabins in peace.’ Having said this, he made us enter his own, in which were a crowd of people; they devoured us with their eyes, but, nevertheless, observed profound silence….After We had taken our places, the usual Civility of the country was paid to us, which consisted in offering us the Calumet. This must not be refused, unless one wishes to be considered an Enemy, or at least uncivil; it suffices that one make a pretense of smoking. While all the elders smoked after Us, in order to do us honor, we received an invitation on behalf of the great Captain of all the Ilinois to proceed to his Village where he wished to hold a Council with us. We went thither in a large Company, For all these people, who had never seen any frenchmen among Them, could not cease looking at us. They Lay on The grass along the road; they preceded us, and then retraced their steps to come and see us Again. All this was done noiselessly, and with marks of great respect for us. When we reached the Village of the great Captain, We saw him at the entrance of his Cabin, between two old men,–all three erect and naked, and holding their Calumet turned toward the sun. He harangued us In a few words, congratulating us upon our arrival. He afterward offered us his Calumet, and made us smoke while we entered his Cabin, where we received all their usual kind Attentions. Seeing all assembled and silent, I spoke to them by four presents that I gave them.”[55]

3. If you are able to read French handwriting, the following 18th century document provides an alternative peace accord to the one mentioned earlier in the text. What can you learn from this document? What metaphors did they use? What style of oratory is present? How was this treaty settled?

4. The ceremony in which Jean Cavelier was forced to cross legs with two women proved uncomfortable for the priest. However, had he paid attention, he would have learned a great deal about the Caddos. Examining this paragraph once again, what do you imagine the various items and placements signified in their world view? What did they communicate?

“The master of the ceremonies brought two maids, the one having in her hand a sort of collar, and the other an Otter’s skin, which they plac’d on the wooden forks above mentioned, at the ends of the pipe. Then he made them sit down, on each side of Monsieur Cavelier, in such a posture, that they looked upon the other, their legs extended and intermix’d, on which the same master of the ceremonies laid Monsieur Cavelier’s legs, in such manner, that they lay uppermost and across those of the two maids. Whilst this action was performing, one of the elders made fast a dy’d feather to the back part of Monsieur Cavelier’s head, tying it to his hair. [56]

5. Once Arkansas Post fell into Spanish hands, a few of the Spanish Commandants had some things to learn about interacting with the Quapaws. Analyze the following text and determine what the actions and reactions were and why they happened the way they did. What promoted the reactions on either side of the coin, so to speak?

“Leyba entertained the Quapaws for several days following his arrival at the post. The commandant felt that he had been as generous as he could be, given that his superiors had ordered him to economize. He hosted Cazenonpoint and other chiefs for several meals at his own table. On the 350 other attendant Quapaws, Leyba lavished a cow, a 280-pound barrel of flour (which he had to borrow from a local Frenchman), and fifty-seven bottles of brandy. He expected these large expenditures to please the Quapaws. But instead Cazenonpoint took offense at Leyba’s attempts to economize. At one dinner, Leyba neglected to provide presents to the dozen men in the chief’s retinue, so Cazenonpoint distributed food to them from Leyba’s own table. After several days of these dinners, Leyba tried to free himself from the obligation. He informed the chief that he was not invited to dinner that night because Leyba himself would not be eating. Incredulous and offended, the chief left without saying a word or giving Leyba his hand. He later declared to the interpreter that ‘it was impossible that [Leyba] was not going to eat dinner.'”[57]

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 123-125. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 131-137. ↵

- Linda C. Jones, “François Danbourné: Colonial Courier,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Spring 2021): 52; Sabo, “Rituals," 79. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 141; Sabo, "Rituals," 78-79. ↵

- Morris S. Arnold, The Rumble of a Distant Drum: The Quapaw and the Old World Newcomers, 1673-1804 (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000), 16-18; Jones, Shattered Cross, 77. ↵

- White, Middle Ground, 21; Jones, Shattered Cross, 142. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 127. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 155. ↵

- Margry, "Récit de Nicolas de la Salle-1682," Découvertes, vol. 1, 553-54. ↵

- George Sabo, “Inconsistent Kin: French-Quapaw Relations at Arkansas Post,” in Arkansas Before the Americans (Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 40), ed. Hester Davis (Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1991), 105-30; Joseph Patrick Key, “The Calumet and the Cross: Religious Encounters in the Lower Mississippi Valley,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61 (summer 2002): 158; Sabo, "Rituals," 79. ↵

- Key, “Calumet and Cross,” 157. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 445. ↵

- “Saint-Cosme,” ASQ, Lettres R, no. 26, pp. 15-16. ↵

- Kathleen DuVal, The Native Ground (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 89. ↵

- Patricia D. Woods, “The French and the Natchez Indians in Louisiana: 1700-1731," Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 9, no. 4 (Autumn 1978): 419; Bienville to Pontchartrain, January 2, 1716, Mississippi Provincial Archives [hereinafter MPA], III, 194. ↵

- Woods, “French and Natchez," 420; Bienville to Raudot, January 20, 1716, MPA III, 198; Du Clos to Pontchartrain, June 7, 1716, MPA III, 209; Marcel Giraud, Histoire de la Louisiane Française. Années de Transition, 1715-1717 (Paris, 1958), II, 178-79; Charles E. O'Neill, Church and State in French Colonial Louisiana: Policy and Politics to 1732 (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 1966), chapter 3. ↵

- Thwaites, "Relation of 1640-41," JRAD, vol. 21 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1898), 47. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 446-447. ↵

- Henri Joutel & Melville Best Anderson, Joutel’s Journal of LaSalle’s Last Voyage (Chicago: Caxton Club, 1896), 146-48. ↵

- Juliana Barr, “A Diplomacy of Gender: Rituals of First Contact in the ‘Land of the Tejas,’” The William and Mary Quarterly 61, no. 3 (2004): 431. ↵

- George Sabo, “Encounters and images: European contact and the Caddo Indians,” Historical Reflections 21, no 2 (1995): 231. ↵

- Laudonnière, Three Voyages, 78. ↵

- Laudonnière, Three Voyages, 79-80. ↵

- Laudonnière, Three Voyages, 81-82. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 127; Nöel Baillargeon and Danielle Aubin, Les Missions du Séminaire de Québec dans la Vallée du Mississippi 1698-1699 (Québec: Service des Archives et de la Documentation, Musée de la Civilisation, 2002), 92n36; Pierre Margry, Découvertes et Établissements des Français dans l’Ouest et dans le Sud de l’Amérique Septentrionale (1614–1754): Mémoires et Documents Originaux, vol. 4 (Paris: Imprimeur D. Jouaust, 1876–1886), 415. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 127-28; D’Iberville, Gulf Journals, 129–130. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 128; Christina Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 4. ↵

- John Gilmary Shea, Early Voyages Up and Down the Mississippi (Albany, NY: Joel Munsell, 1861), 137. ↵

- Shea, Early Voyages, 137; Jean Delanglez, French Jesuits in Lower Louisiana, 1700–1763, (Washington, D. C.: Catholic University of America, 1935), 15n99. ↵

- Laudonnière, Three Voyages, 83. ↵

- Cook, Jacques Cartier, 55-56. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 143-145. ↵

- “Saint-Cosme,” ASQ, Lettres R, no, 26, p.13; Jones, Shattered Cross, 74. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 467-471. ↵

- Key, “’Outcasts,” 274. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 35. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," vol. 59, 159. ↵

- Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, Histoire de la Louisiane, vol. 3 (Paris: De Bure, l'aine, 1785), 7-8. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 441, 447, & 452. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 37-38; Pierre Antoine Simon Maillard, An Account of the Customs and Manners of the Micmakis and Marichheets Savage Nations, Now Dependent on the Government of Cape-Breton (London, 1758), 35. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 38; Alexander Henry, Travels and Adventures in Canada and the Indian Territories, between the Years 1760 and 1776, in Two Parts (New York, 1809), 75. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 22. ↵

- James W. Parins, John Rollin Ridge, His Life and Works (University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln: 2004), 123. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 93; “de Montigny,” ASQ, Missions, no. 41, p. 14. ↵

- Harvey, Native Tongues, 37; Havard, Montreal 1701, 26. ↵

- Havard, Montreal 1701, 28. ↵

- Havard, Montreal 1701, 33. ↵

- Havard, Montreal 1701, 44. ↵

- Havard, Montreal 1701, 22. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 151; Key, “Calumet and Cross,” 162. ↵

- Havard, Montreal, 1701, 23. ↵

- DuVal, “Fernando de Leyba,” 27. ↵

- Kathleen DuVal, “A Good Relationship, & Commerce”: The Native Political Economy of the Arkansas River Valley,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal I, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 71. ↵

- Thwaites, "Gravier's Voyage," JRAD, Vol. 65 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1899), 119-123. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage, JRAD, vol. 59, 115, 117, 119. ↵

- Joutel & Anderson, Joutel’s Journal, 146-48. ↵

- DuVal, "Fernando de Leyba," 10-11. ↵