3 Art, Objects and Imagery

When you look at art, what do you see? Art for arts sake or something more? Signs? Symbols? Spirituality? A story? Native peoples used art, objects and imagery to communicate among themselves, with others, and with their spirit world during the colonial period. French missionaries also used art and objects for their own spiritual purposes but also to try and teach Christianity to Native peoples. So, how do you “read” visual objects? What can and/or do they communicate? Reflect on these thoughts and questions as you read this chapter on art, objects and imagery and their use to communicate within and between cultures.

As Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet journeyed southward along the Mississippi in the 1670’s, “while skirting some rocks” they saw two monsters painted on a high bluff next to the water

“which at first made Us afraid, and upon Which the boldest [Indians] dare not Long rest their eyes. They are as large As a calf; they have Horns on their heads Like those of a deer, a horrible look, red eyes, a beard Like a tiger’s face somewhat like a man’s, a body Covered with scales, and so Long A tail that it winds all around the Body, Passing above the head and going back between the legs, ending in a Fish’s tail. Green, red, and black are the three Colors composing the Picture. Moreover, these 2 monsters are so well painted that we cannot believe that any [Indian] is their author; for good painters in France would find it difficult to paint so well,–and, besides, they are so high up on the rock that it is difficult to reach that place Conveniently to paint them.”[1]

Marquette is the first known Frenchman to have described the Piasa–a small, supernatural spirit that Native peoples believed attacked people, particularly travelers along the rivers.[2] Placed between the mouths of the Illinois and the Missouri rivers, this spiritual symbol served to forewarn individuals of the rapids and muddied, debris-choked waters at the intersection of the Missouri and the Mississippi Rivers. This dangerous junction likely swallowed up many poor souls who traversed this intersection particularly when water ran high.

The stunning artwork had a significant impact on Father Marquette, so much so that he described it in detail and took the time to draw it. Some fourteen years later, the original drawing remained visible on a bluff along the great river. Henri Joutel happened upon it as he and four Quapaws journeyed up the Mississippi River towards the Illinois country. “The 2nd [of September], we arrived at the point of Marquette’s so-called monster,” that the Jesuit priest had written about. “This monster consists of two meschantes figures, drawn in red on the face of a rock, eight or ten feet up.” Unexpectedly, Joutel’s Quapaw guides abruptly stopped their journey to offer a sacrifice to the painting. Not understanding the Piasa’s spiritual significance, Joutel and his men sought to disrupt the Quapaws’ efforts to pray for safety to their spirit world. Joutel wrote: “despite our efforts to have them understand that this rock had no value, and that we worshiped something much bigger, in showing them the sky [heaven]…this was pointless, and they showed us by signs that they would die if they did not fulfill this [sacrificial] duty.”[3] The Piasa had to be recognized and acknowledged. The Quapaws had to communicate with their spirit world to ensure that their safe journey continued.

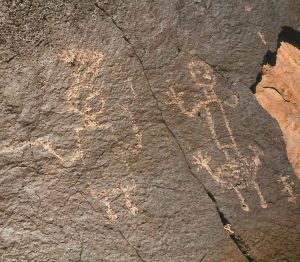

Native peoples used artwork, imagery, and objects to express their spirituality, to communicate information to themselves and others, to mark an important location, and other uses. Indeed, some of the earliest artwork in North America can be found just to the west of Albuquerque, New Mexico, in an open, rocky area below several extinct volcanoes. Today, the Petroglyph National Monument is full of symbolic artwork drawn by the Native peoples who lived in the same region some four to eight hundred years earlier. Some twenty thousand petroglyphs (rock carvings) are etched into black lava boulders created from long-ago eruptions. These images depict events and characters from Pueblo mythology, and are important for regional Native communities today just as they were to the petroglyph makers who created them. Some of these drawings personify natural forces while others remind us of historical or even mythical events. Consequently, “their meanings are layered and overlapping, not easily summed up in a phrase or two.”[4]

Among the thousands of petroglyphs found at this site, symbols and characters represent key elements of Pueblo spirituality and society. Circular symbols, for example, might represent the sun, the moon, a year’s cycle, perhaps even an opening to another world. Another symbol, a cross surrounded by a circle or outline, typically refers to the four directions and perhaps the path of the sun or the moon around them. But other representations are present as well–human-like figures, animals, hand prints, feet, birds, reptiles, and other spiritual characters. Some panels reference hunting–hunters, animals, bows and arrows. Other panels reference agriculture–rain, crops, sun, harvest. Furthermore, “certain icons [may] represent clan ancestors who could mediate between this and the spirit world, and may have been the focus for ceremonies and rites of passage.”[5]

Well east of the Mississippi, in southwestern North Carolina, another rock art site communicates an important legend among the Cherokees. Known as Judacalla Rock, this is a collection of some 1500 different petroglyphs, the most of any bluff site east of the Mississippi River. For the Cherokees, this rock may have served as a boundary marker for important hunting grounds, guarded over by Judaculla from his Devil’s Courthouse, his judgement seat. A legendary giant and master of all animals who lived in the Balsam Mountains overlooking the region, Judaculla was described as being over seven feet tall, with seven fingers on each hand, seven toes on each foot. (Click on this link to see a video from Cherokee Nation that further describes Judaculla Rock.)

Within the Mississippi River Valley, numerous pictographs and petroglyphs exist along the Arkansas River and within Petit Jean State Park. They include “curvilinear double-line motifs and parallel wavy lines transected or ‘slashed’ by perpendicular lines,” as well as naturalistic images such as plants and animals, ceremonial objects, human figures, astronomical features, concentric circles, and cross-circle motifs.[6] Among them, headless anthropomorphic images seem to reflect historically documented legends of celebration of life over death through the culture hero named “Morning Star” or “Red Horn.” There is even a hellgrammite, otherwise known as a dobsonfly larva, which symbolizes a life cycle that traverses sky, water and land:

“Adults lay eggs on tree branches that hatch into larvae and fall into streams where they feed and grow until they crawl back onto the land and enshroud themselves within a chrysalis, later to emerge as winged adults. This life cycle traverses the three realms of the Southeastern Indian cosmos: the Above World associated with the sky, the watery Below World, and This World, comprising the surface of the earth inhabited by communities of living beings.” This very special “allegorical” being is “capable of crossing from one ‘world’ to another as it navigates transitions from one form or state to another.”[7] Thanks to the Arkansas Archeological Survey, you can access an online rock art database and see many of these and other rock etchings and paintings that are prevalent in Arkansas.

Robes, Pottery and Shells

Among the many nations along the Mississippi River and on into the Pays d’en Haut, visual objects most certainly communicated something important from the artist to the viewer or spirit world. The Quapaw Three Villages Robe was given to the French sometime in the mid-eighteenth century. This prepared deerskin portrays three of the traditional villages of the Quapaws—Osotouy, Tourima, and Kappa—along with core traditions of this Arkansas nation. Quapaw long houses are portrayed from their portal end and two calumets, one for war and one for peace, draw the two sides of people towards them. One side of the robe presents the Sky People who were responsible for the spiritual needs of the community. On the opposite side of the robe, one sees the Earth People who oversaw agriculture and warfare. Nearby, the Chickasaws, longtime enemies of the Quapaws, kneel with arms drawn, while others flee. The Quapaws confront their arch enemy with bows and arrows and long guns. Two Frenchmen dressed in knickers and boots lazily lean amidst four French structures, smoking from long clay pipes. Another Frenchman stands and holds an unknown object. Drawn by an anonymous Quapaw, the robe reflects elements of Quapaw culture, tradition, and spirituality, and also reflects their rather unique interpretation of the French.[8]

But other 17th and 18th century robes survive that also display Native spirituality and thus communicate such information to the viewer. The Thunderbird Robe portrays a great spirit, “one who is preeminent above the others…because he is the maker of all things.”[9] Although identified as Illinoian, the robe’s symbolism is remarkably relevant to Velma Seamster Nieberding’s description of Wah-Kon-Dah, the great spirit of the Quapaws: “Everything they [the Quapaws] had came from Wah Kon Dah, the great over-all spirit….Wah Kon Dah was of the sky-world from where they had fallen into the water in the creation time. He was remote, fearful and occasionally dangerous, but always the highest. His rays must warm mother earth before the seeds could grow in the spring and must ripen the corn before they could use it in summer. Their lives were regulated by the rising and setting of the sun. He was the master of all life.”[10]

As you look at the Thunderbird robe, note that the central figure is a geometric bird, the overarching spirit, with wings extended downward. Circles surround this bird—black, grey and red—and likely represent each of the important, complimentary realms of their balanced world view, the spiritual realm, the earth realm, and the aquatic realm. Circular shapes symbolize their perpetual, unending presence. Their randomization across the robe symbolizes their manifestation throughout creation. The Great Spirit thunderbird watches over these important elements. As master of all, this great spirit can go no lower, no higher.[11]

Reflect upon these robes and be prepared to discuss them:

- What do the robe images reveal about the world the Quapaws inhabited at the time of its creation?

- Why is Arkansas Post depicted on this robe? What does it signify for either culture?

- What does the three villages robe communicate about the French/Quapaw relationship?

Aside from painted robes, other art forms symbolized and thus communicated the sacredness of animal spirits, manitous and the like. The Quapaws, the Tunicas and the Caddos, among others, developed animal and human effigy pots that likely served as representations of one’s manitou, or particular manitous of importance to a given culture. These sacred vessels were likely used in ceremonies to communicate with the spirit world or simply to serve as a representation of the varied worlds, typically upper and lower worlds, of utmost importance within one’s lifeway or spiritual realm. Among the Taensas who lived in what is today Northeastern Louisiana, their sacred temple “contained the eternal flame, grossly sculpted statues of men and animals, and several cases full of bones in honor of the most considered chiefs who had died.”[12]

The Tunicas, located initially along the Yazoo River and later near present-day Angola, Louisiana, reverenced spiritual forces within nature such as animals, plants, water and sky. Like the Taensas, they also had a hallowed temple, raised on a mound in the center of their village. Within their temple, they maintained a sacred fire that preserved stability and balance within their worlds. To visually acknowledge the two worlds (sky and earth), the temple housed two earthen statues—a female deity of the sun representing the sky world and a frog, representing the earthly world.[13]

Native peoples crafted other symbolic and communicative art forms. The Caddo Indians told spiritual stories through the use of delicately etched and decorated conch shells. A series of these shells recovered from Spiro Mounds in Oklahoma tells a story of the above world and the below world within Caddo tradition. (Click on this link to see retired Arkansas archeologist Dr. George Sabo’s discussion of these shells.) Caddos and Quapaws also created “head pots” to communicate a visual representation of death. Within both cultures, these powerful expressive pots preserved important information that offers a window into one’s appearance–hair designs, tattoos, nose and ear piercings, anatomically accurate facial features–during their time of creation.

Another art form, wampum belts, artistically and symbolically expressed treaties and even locations and paths (maps) to individuals through various patterns, colors, and designs.

(Click on the image to view a video focused on the creation of wampum belts. Once completed, watch this additional video that describes how one made the individual shell beads.

(Click on the image to view a video focused on the creation of wampum belts. Once completed, watch this additional video that describes how one made the individual shell beads.

During the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701, these collars or belts were “a kind of contract without which it is impossible to include any significant business with the [Native people].”[14] In preparation for the “Great Peace,” Native women made dozens of wampum belts, in various styles and colors:

“Their size, their colour, and the symbols created by the alternation of white and purple (often called black) beads were never random. A belt had great symbolic value in negotiations; the colour white symbolized peace and life, purple symbolized mourning, and a belt painted red meant war. The purpose of the wampum was to validate, in a ritualized way, the words that were spoken. After reciting the proposal that accompanied each belt, the speaker laid the wampum at the feet of the person addressed. Its acceptance meant that the message would be taken into consideration, but it could also be rejected. It was not the wampum itself that was important to Native people, but its use and the process of gift exchange that resulted from its acceptance….Because of the symbols woven into wampum, however, it had an archival value, serving to preserve the nation’s oral memory.”[15]

Wampum belts shared and preserved very significant information, some of which may be important to the Quapaw robe mentioned earlier. One wampum belt, for example, “originally showed five equally spaced human figures in white on a purple background. The five figures were represented as holding hands, but with their elbows crooked to indicate that any of the nations could leave the Confederacy, though not without weakening it and leaving its protection.”[16] Examine the Quapaws’ Three Villages Robe more closely, in particular the Sky People. Historically, we know that two Quapaw villages merged at one point (there were originally four). On the robe, there are only three villages represented. Among the Sky People, the way they hold hands varies from person to person. The first two people are hand in hand. The next couple holds onto them by the elbow but is also hand in hand. The final group, five in all, also holds onto the middle group by the elbow.

Reflect upon the following and be prepared to discuss:

Look at the way the Sky people hold each other. What might this signify?

What might we infer about the Quapaw Sky People and the original four villages?

What might the Quapaws be saying within this artistic design?

Winter Counts

Because Native American languages were not initially written down, some Native peoples used artistic means to document their history. Among the Plains Indians, “winter counts” were one such way of recording important tribal information based on an annual pattern that began with the first snowfall of the year and then ended with the first snowfall of the following year, thus a winter. Towards the end of the year, community elders gathered to determine the most significant event of the past year. The designated keeper or story teller then added the event in the form of a pictograph or a painted image or icon to the animal skin.

Nakota Sioux Lone Dog documented some seventy-one years (1800-1871) of the Yanktonais people, Nakota Sioux speakers. (Click on this link to watch a video that describes this important winter count.) In the visual closeups that follow, the first symbolizes a worldwide phenomenon that took place in November of 1833–the Leonid Meteor Shower. The second contains numerous hoof prints surrounding a larger circle. What might this signify? The video gives you some clues. Still others represent important health challenges, trade, treaties, battles, peace and so on.

Aside from the first two drawings discussed just above, what do you believe the second two images represent?

Keeping a winter count was a serious, careful process designed to preserve experiences of importance to a given nation. Originally, keepers of the winter count used tanned leather, buffalo or elk to support their winter chronicles. As Americans pushed west and wiped out large game, Native keepers of the winter count used new materials such as cloth and paper. Today, several surviving winter counts are drawn in books, on other forms of paper and parchment, and even on muslin cloth. Some winter counts even remain preserved through written, chronological text. (Through this link, you can see Lone Dog’s written descriptions by year.) Whether drawn or written, winter counts were and are important to the history of the Native peoples to which they are connected.

Quirts

Aside from pottery, robes and winter counts, artistically enhanced weapons could communicate important information about their owner or events in the life of the community. The quirt, a whip that one used to urge a horse along, was also used by a warrior in battle to touch the enemy without coming to any harm. When a touch or a “coup” was made, it was considered an act of bravery, a strike. To chronicle these “coups”, the owner sometimes decorated his quirt with etchings of animals, birds, calumets, even humans. Biographic elements such as hoof prints showed the number of horses captured; human busts indicated the number of humans killed, captured, or touched with the quirt, thus a counting of one’s “coups.” The example presented here is housed at the Smithsonian Institute and includes “combat and horse-stealing scenes, vanquished enemies, and clusters of horse tracks….”[17]

European Artwork

Native artwork communicated spirituality and other important elements of a nation’s traditions and lifeway, but so too did European art which French missionaries presented to Native peoples to communicate Christian stories and traditions, to teach the catechism and to expose European culture to them. The use of imagery in Catholicism was nothing new. Students at the Petit Séminaire de Québec, a secondary school in Québec City, prayed before paintings of St. John the Evangelist, the Holy Mother, or any number of the Apostles.[18] Students and parishioners alike also used images to enhance or reflect one’s devotion to God. Indeed, “each holy day and Sunday, one exposed by dawn on one’s door the image of his or her patron saint, to remember to honor him or her.”[19] The first Bishop of Québec, François de Laval, used imagery to increase Québec’s devotion to the Holy Family (Jesus, Mary and Joseph). He “had printed in France an image of the Holy Family that he circulated . . . in great number in his diocese.”[20]

French missionaries attempted to teach Native peoples with artwork that expressed the Holy Mysteries and Stories of the Christian faith, “the Annunciation and the crucified and risen Christ, among others.” Father Jacques Marquette, for example, hung four large portraits of the Virgin Mary in an open field to teach the Illinois of Christ’s birth:

“It was a beautiful prairie, close to a village, which was Selected for the great Council; this was adorned, after the fashion of the country, by Covering it with mats and bearskins. Then the father, having directed them to stretch out upon Lines several pieces of Chinese taffeta, attached to these four large Pictures of the blessed Virgin, which were visible on all Sides. The audience was Composed of 500 chiefs and elders, seated in a circle around the father, and of all the Young men, who remained standing….The father addressed the whole body of people, and conveyed to them 10 messages, by means of ten presents which he gave them. He explained to them the principal mysteries of our Religion, and the purpose that had brought him to their country. Above all, he preached to them Jesus Christ, on the very eve (of that great day) on which he had died upon the Cross for them, as well as for all the rest of mankind; then he said holy mass.”[21]

The Jesuit Father Jacques Gravier also used biblical images to teach Christianity to the Illinois and had his most successful Kaskaskian convert, Maria Rouensa use these same images to teach Christianity to her Native community. As Gravier wrote:

“This young woman, who is only 17 years old, has so well remembered what I have said about each picture of the Old and of the New Testament that she explains each one singly, without trouble and without confusion, as well as I could do–and even more intelligibly, in their manner. In fact, I allowed her to take away each picture after I had explained it in public, to refresh her memory in private. But she frequently repeated to me, on the spot, all that I had said about each picture; and not only did she explain them at home to her husband, to her father, to her mother, and to all the girls who went there,–as she continues to do, speaking of nothing but the pictures or the catechism,–but she also explained the pictures on the whole of the Old Testament to the old and the young men whom her father assembled in his dwelling.”[22]

Some missionaries had images manipulated to reflect the Native peoples to whom they were shown–clean-shaven individuals, with straight hair, without halos or hats.[23] But a more creative form of imagery came from Father Jean Pierron who created his own images to learn the language at hand. As the peoples present watched him draw or paint, they verbally identified objects or symbols he created. This experience not only enhanced his comprehension, but also allowed him, he believed, to better express Christianity to the Native community within which he served.[24]

No matter how missionaries obtained images, they used them “to provide a sustaining, cognitive impression, a visual connection to the verbal lessons given so as to help the Native people remember and hopefully embrace the sacred mysteries ‘with a recognizable form of reality.’”[25] The extent to which the Native peoples understood the content of European images and embraced what they truly symbolized remains unclear, for “interest in them may have been related as much to perceptions of the images as powerful in themselves, as representations or objects of power, as to the more mundane pedagogical concerns.” For example, some Native peoples might sacrificially offer food or tobacco at Jesus’ image during ceremonies and feasts. In sharp contrast, others might demolish images out of fear of their unknown power.[26] Nonetheless, some missionaries encouraged their Native converts to “mix traditional native practices with the new rituals.” As such, some Indians “continued to bring gifts to the images in the chapel.” One Huron congregation, in particular, “adopted a pious practice of making a little present every Sunday to the Virgin, each one giving a porcelain bead for each rosary recited during the previous week.” Some continued to use tobacco, likely “following the native custom of using tobacco to propitiate forces in the spirit world.”[27]

Communication through Objects and Architecture

Objects and architecture (houses, temples and such) also played important communicative roles along the Mississippi. In the case of architecture, Dhegihan Sioux communities, such as the Quapaws and the Osages, visually and spiritually communicated order and unity within their society through the layout of their villages. Both nations lived in long houses. A central road through the village divided the Sky People who lived on the north side from the Earth People who lived on the south side. This spatial arrangement “sustained the entire web of relationships connecting human and spiritual communities,” and showed that these nations were “a unified whole that was greater than the sum of its constituent parts.” Indeed, some 150 miles to the west of the Quapaws, a distinct environment-based, spatial pattern models their village architecture and spirituality within the Arkansas River Valley. Following the north/south division, pictographs on the south side of the river represent animals, plants, and anthropomorphic figures, drawings representative of the Earth People. Pictographs on the north side of the river represent mythic themes, representative of the Sky People.[29] As such, this collection of Native drawings shows “the fundamental interconnectedness of life,” and the importance of spirituality in the world view of Dhegihan Sioux groups such as the Osages and the Quapaws.[30] We will explore this again in Chapter 5.

In addition to architecture and environmental spatial design, objects symbolically communicated information. For Jesuit and Seminary missionaries, a cross symbolized Christianity; rosaries served as a tool for prayer as well as a symbol of success in learning. Frenchmen, in general, used guns, flags and other cultural objects to demonstrate power and superiority, allegiance to king and country. But interpretation and understanding of these objects by Native peoples varied. Take the European-style clock. Some Jesuits had to hide this device from the Native peoples “for they believed it to be the Demon of death.”[31] In 1636, the French Jesuit, Jean de Brébeuf described the reactions he witnessed among several Native individuals:

“As to the clock, a thousand things are said of it. They all think it is some living thing, for they cannot imagine how it sounds of itself; and, when it is going to strike, they look to see if we are all there and if someone has not hidden, in order to shake it. They think it hears, especially when, for a joke, some one of our Frenchmen calls out at the last stroke of the hammer, ‘That’s enough,’ and then it immediately becomes silent. They call it the Captain of the day. When it strikes, they say it is speaking; and they ask when they come to see us how many times the Captain has already spoken. They ask us about its food; they remain a whole hour, and sometimes several, in order to be able to hear it speak. They used to ask at first what it said. We told them two things that they have remembered very well; one, that when it sounded four o’clock of the afternoon, during winter, it was saying, ‘Go out, go away that we may close the door,’ for immediately they arose, and went out. The other, that at midday it said, yo eiouahaoua, that is, ‘Come, put on the kettle;’ and this speech is better remembered than the other, for some…never fail to come at that hour, to get a share of our Sagamité.”[32]

Crosses, rosaries, paintings, maps, clocks–all were meant, in part, to persuade Native people of the presumed superiority of Europeans in terms of culture, technology and Christianity. Alternatively, objects helped the missionaries learn Native languages in much the same way that language teachers use pictures and various realia: “to elicit vocabulary, practice basic sentence structures, and make lessons more interesting.”[33] Objects mattered not just in what they were but in what they represented and/or symbolized. For example, the French and the Quapaws had long been allies since their first encounter in 1673. As the decades passed, and to keep their alliance strong and healthy, the French gave the Quapaws significant medals to affirm their allegiance. After the French and Indian War, “ownership” of the western Mississippi River Valley including the Arkansas River fell to the Spanish. To establish and solidify alliance with the Quapaws, the Spanish and their young, designated Arkansas Post leader, Fernando de Leyba, prepared an elaborate ceremony in 1771 so to give the Quapaws a Spanish medal to symbolize their newfound relationship, and replace any French medals formerly given.[34]

The Quapaws’ great chief, Cazenonpoint, expected to exchange his French medal for a new, perhaps larger, shinier Spanish one, signifying a shift in alliance from the French to the Spanish. But to the chief’s great shock and dismay, the Spanish medal was small and very unimpressive. Declaring that the Spanish had cheated him, Cazenonpoint demanded his French medal be returned, since “through the clumsy error of a skimpy medal, the Spanish had insulted the Quapaws and endangered their alliance.”[35] Cazenonpoint expected the new Spanish medal to not only symbolize the Quapaw-Spanish alliance, but also “his own stature as great chief.” But the Spanish misinterpreted the extent to which this medal symbolized the importance of the Quapaws within their new regime. A smaller medal suggested that a Quapaw alliance meant less to the Spanish compared to the Quapaws’ long-standing alliance with the French. It was personal as well: “European medals, flags, and other symbols of recognition enabled chiefs and warriors to signify their status to other Indian peoples and white traders as well as to their own people. Influence within Cazenonpoint’s tribe depended on prestige, which was always provisional and depended upon possessions rich in the symbolism of power. For Cazenonpoint to surrender a larger for a small smaller medal could be seen as a ritual diminution, which would open him up to a ridicule fatal to his standing among his people.”[36] Eventually, the Quapaws accepted a Spanish medal and wore it both to show allegiance and later dismay, for once the Americans arrived, the Quapaws “continued to wear medals given them by the Spanish to make the point that they had not ‘received any such token of friendship’ from the U.S.”[37]

Native communities had other objects vital to their spirituality. Personal, sacred bundles, for example, contained items of importance to an individual’s spirit or manitou. Sometimes such bundles were given to Frenchmen and other visitors to communicate alliance, or even a kinship relationship that placed individuals within the bounds of the Native society. Henri Joutel’s entourage received one of these sacred bundles while among the Quapaws. Though not laden with goods, Joutel and his men understood that balance was essential in their growing relationship and asked the Quapaws, through the French interpreter, Jean Couture, “to wait until our return [from France], when we would have more goods in our possession, and that we would then strike the pole” during the calumet ceremony. Content with this arrangement, “the Quapaws took the calumet, in which they placed some tobacco, and presented it to M. Cavelier…I [Joutel] gave them some bits of tobacco from France, or rather the islands that I had, so as to honor their calumet; they smoked it, then took the calumet, put it in a deerskin pouch, with the items that held it, and came to present it to M. Cavelier with several otter skins and porcelain necklaces.”[38]

Giving the sacred calumet bundle to M. Cavelier spoke words of peace and trust for their relationship, while Joutel’s promise to return, to provide additional gifts and to strike the pole highlighted their desire to remain reciprocally balanced and trustworthy as well. But while these sacred bundles expressed words of peace and relationship when reciprocally offered, Native peoples in general did not so easily give up their manitou bundles, as Father Marc Bergier learned while living among the Tamarois, a community of Illinois-related people who lived across from modern-day St. Louis in the early 18th century. During an epidemic, the weary priest urged the Tamarois to abandon their manitous, their sacred bundles representative of their original vision quest and instead embrace what he believed were the transformative powers of Christianity. He worked so hard that “the oldest and most superstitious of Tamarois brought him those things they had yet to detach from,” their manitou bundles.[39] But Bergier suffered from illness and soon died. The lack of sadness upon his death could not have been any more profound and telling. Bergier’s refusal to exchange gifts with the Tamarois–to dismiss the gift as “the word”–had created an impermeable wall of mistrust and prevented a lasting bond between the two cultures from taking hold. Upon his death, the Shamans and villagers believed that Bergier’s Christian manitou had failed him. To the Tamarois, his death was a victory. They were certain that their personal manitous had spoken and had defeated Bergier’s Christian cross spirit. “They gathered around the cross that he had erected, and there they invoked their manitous, each one dancing, and attributing to himself the glory of having killed the missionary, after which they broke the cross into a thousand pieces.”[40]

Bundles and crosses had distinctly different meaning for French and Native peoples. But the most sacred of all, the one almost mutually understood by both sides, was the highly decorated and symbolic calumet. “There is nothing more mysterious or more respected among them. Less honor is paid to the Crowns and scepters of Kings than the Native peoples bestow upon this. It seems to be the God of peace and of war, the Arbiter of life and of death. It has but to be carried upon one’s person, and displayed, to enable one to walk safely through the midst of Enemies–who, in the hottest of the Fight, lay down Their arms when it is shown.”[41]

Bundles and crosses had distinctly different meaning for French and Native peoples. But the most sacred of all, the one almost mutually understood by both sides, was the highly decorated and symbolic calumet. “There is nothing more mysterious or more respected among them. Less honor is paid to the Crowns and scepters of Kings than the Native peoples bestow upon this. It seems to be the God of peace and of war, the Arbiter of life and of death. It has but to be carried upon one’s person, and displayed, to enable one to walk safely through the midst of Enemies–who, in the hottest of the Fight, lay down Their arms when it is shown.”[41]

The mere presentation of the calumet helped to determine if one came as friend or foe, longed to be ally or enemy. Indeed, the French saw the calumet as “a useful element of frontier diplomacy” which “created bonds of friendship that allowed for secure passage, trade relations, and defensive support between the two groups,” nothing more.[42] Alternatively, Native communities like the Quapaws found balance, order and unity from the calumet and its subsequent presentation to others “according to a principle of complementary opposition in which separate but equal descent lines were linked by the rule of reciprocity.” Thus, the celebration of the calumet “extend[ed] this principle to relations with outsiders through the creation of ‘fictive’ or ancillary kinship relations.”[43]

This powerful object remained an important part of Quapaw culture well into the late 18th century, though not always with great enthusiasm on the part of the Spanish who took over the region from the French in 1763. Their then leader, Demazilliers, remarked in 1770: “A minor chief will have a pipe dance with the Tonicas. We’ll try to stop this, but we have to be careful.”[44] Undoubtedly, the Spanish had some distrust of the Quapaw tactics, certain that their sharing of this symbol with Native peoples away from Arkansas Post had more sinister means than a symbol of relationship. Indeed, not one year later, a second letter described the Quapaws’ sharing of the calumet with multiple Native peoples: “The Arkansas Indians are going to circulate the calumet through 25 men to the villages of the Tonikas, Bilocesis [Biloxis], Chacas, Apalaches and Cados to secure horses for a long trip.”[45] No fear emerged since this offering of the calumet seemed more obvious to the Spanish. But the calumet could also serve as an insult rather than a sign of peace. In 1773, the Quapaws had noticed tracks around their village and assumed they were made by the Osages. The Quapaws sent out a party and accumulated several scalps as a result, although the Spanish had hoped that the Quapaws would approach the Osages peacefully. Despite Spanish preferences, the Quapaws had their own views, since the Osages “approach[ed] their villages without the chief bringing the Long Pipe in order to insult them.” The Quapaws were certain that the Osages sought to draw them out and attack them, likely abusing the true spirit of the calumet.[46]

The Journey of the Quapaws’ Three Villages Robe

Native objects, art and imagery communicated something sacred, spiritual, life sustaining. Fortunately some of these articles survive–in private collections, Native individual’s homes, local, national, and international museums, archival collections and Native communities. Some are well preserved while others have suffered greatly, with some owners failing to understand the significance and sacredness of these items. Indeed, one can trace the manner in which the Quapaw and Illinois robes were treated by the French in the 18th through the 21st centuries. Europeans did not understand nor honor their spiritual significance. Instead, many simply found them mere curiosities rather than honoring them for what they represented and communicated through their designs, symbols and colors.

The Three Villages robe mentioned at the start of this chapter is actually one of eighteen robes that were given to the French in the mid 18th century. The Comte d’Artois, brother of King Louis XVI, asked the tutor of the King’s children, the Marquis de Sérent, to create a Cabinet de Curiosités (curio cabinet) to help the young royals learn about the Native peoples of New France. Sérent approached a former official in the Department of Colonies and the Royal Navy, Monsieur de Fayolle, and offered to purchase his rich collection of items from America. Despite a value of 30,000 livres, Fayolle sold his cabinet to the Marquis in 1785 for 15,000 livres and an annual pension of 600 livres. Unfortunately for Fayolle, the entire sum was never paid. Instead, D’Artois and Sérent likely forced him to sell the collection against his better judgement.[47]

Sérent soon found that the Palace at Versailles could not accommodate the royal children and the collection that held some 200 pieces from Canada and Louisiana alone. Consequently, he moved the precious items to the Hotel de Sérent, 6, rue de Reservoir in Versailles to serve as his tutoring center for the royal children. But once the French Revolution began in 1789, the status of the collection changed significantly. D’Artois and Sérent fled from Paris, while Sérent’s wife remained behind to oversee the goods in their possession. But her guardianship soon failed and within a matter of months, the cabinet was confiscated. The curiosities were moved to an Ecole Centrale within the Palace of Versailles to teach the people of the republic. Odd as it may sound, the French Revolution may have saved these robes from destruction since “the more thoughtful revolutionaries decided to preserve as the property of the people of France the riches amassed by the ancien regime, rather than to destroy them along with the privileges of the ruling class.”[48]

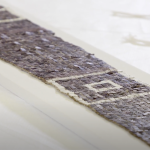

By 1792, the collection was once again under the management of M. de Fayolle who, as its conservator, used some seven rooms at Versailles to display the collection. At this same time, de Fayolle developed an inventory of the collection and listed some 362 items from the Americas and India including “18 blankets of the skins of bison [‘Boeufs Illinois’], deer, and other quadrupeds of North America, all prepared and painted by the [Indians] of Canada and Louisiana.”[49] As a part of the inventories written in 1792 and 1806, M. de Fayolle provides some clues as to how these items were used. For example, headdresses listed in these inventories were referred to as “couronne de sauvage,” or Indian crown, a term that “allowed Sérent to communicate a more familiar political system…where a king was ruling his reign.”[50] But de Fayolle also inventoried how some of the artifacts themselves were displayed. Wax mannequins, he wrote, showed “the objects in use and made their function even more explicit.” One mannequin was described as “being dressed in a full complement of Canadian Indian clothing,” with some thirty-five artifacts. When citizens visited the collection, “one made a tour around the Canadian Indian in the room of clothing, utensils, and divinities of different peoples.” The waxed mannequin of a Canadian Indian “was certainly the item that was the most admired.”[51]

After the major events of the Revolution settled down, the Ecole Centrale was removed from Versailles, and the collection of ethnographic artifacts sent to the Bibliothèque Municipale de Versailles in 1806.[52] While in the possession of the Versailles Library, various robes were once again put on display complete with wax heads and mannequins representative of Native Americans. Indeed, old photographs, taken some time after 1869 clearly show ten of the robes, variously hung and folded behind and around waxed figures.

No other photos are known to exist. But if de Fayolle’s collection once contained eighteen robes, where were the other eight? Some clues exist, for by the time these photos were made, two robes had already been sent to the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie de Besançon and one additional robe to Lille, sometime before 1853. Thus, of the original eighteen robes from 1792, the whereabouts of thirteen were known by the end of the nineteenth century. The whereabouts of five were not.

The robes remained in the possession of the library in Versailles for over 120 years, but by the 1930s, the collection was in trouble. Some of the robes were dumped into the basement of the library and were “threatened by complete destruction.”[53] Recognizing their fragile nature, the Vicomte de Noailles wrote a letter dated July 25, 1931 to the Maire of Versailles to ask his city to send the collection to the Musée Ethnographique du Trocadero. This museum, established in 1878 after the World’s Fair, had as its mission to gather in one location the ethnographic goods collected over the centuries that were currently scattered throughout various museums in Paris.[54] As he wrote: “These objects, by virtue of their fragile material, their age, their vulnerability, and destructive insects, demand particular care that the Musée Ethnographique alone can give them, thanks to the specialized personnel and tools….If this is agreeable, the society of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadero would be happy to pay, without delay, and as a sign of gratitude, the sum of 10,000 francs to the Société des Amis de la Bibliothèque de Versailles.”[55]

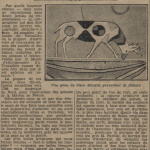

Thus, in 1934, what remained of de Fayolle’s entire collection was transferred to the Musée d’Ethnographie. Shortly thereafter, the newspaper, Le Journal, announced a newly opened exhibit in April 1934: “A conservator who must also be an enthusiastic ethnographer,” unearthed these beautiful, well-crafted treasures after years tucked away in Versailles.[56] By 1938, the robes were moved to the renamed Musée de l’Homme where security faltered. The beautiful Serpent Robe, most assuredly Quapaw in origin, was stolen in May 1982.[57] Still other robes suffered unfortunate embarrassment when used as visuals in advertisements for Sporoline, an antifungal cream. Clearly one seemed more concerned about advertisement and greed than for the sacredness of these treasures. Thankfully, in 2003, the robes found their newest, most secure home at the Musée du Quai Branly, a museum devoted to understanding the peoples of the world. Only nine of the ten robes held at the Musée de l’Homme arrived at the Musée du Quai Branly, while the two robes in Besançon and the one robe in Lille remained in place.

Thus, in 1934, what remained of de Fayolle’s entire collection was transferred to the Musée d’Ethnographie. Shortly thereafter, the newspaper, Le Journal, announced a newly opened exhibit in April 1934: “A conservator who must also be an enthusiastic ethnographer,” unearthed these beautiful, well-crafted treasures after years tucked away in Versailles.[56] By 1938, the robes were moved to the renamed Musée de l’Homme where security faltered. The beautiful Serpent Robe, most assuredly Quapaw in origin, was stolen in May 1982.[57] Still other robes suffered unfortunate embarrassment when used as visuals in advertisements for Sporoline, an antifungal cream. Clearly one seemed more concerned about advertisement and greed than for the sacredness of these treasures. Thankfully, in 2003, the robes found their newest, most secure home at the Musée du Quai Branly, a museum devoted to understanding the peoples of the world. Only nine of the ten robes held at the Musée de l’Homme arrived at the Musée du Quai Branly, while the two robes in Besançon and the one robe in Lille remained in place.

Conclusion

Art, objects and imagery held symbolism and meaning both for the Native peoples as well as the French and other Europeans. Intricately designed in many instances, Native art forms not only communicated important information about one’s personal manitou or one’s prowess in war, but also communicated directly to one’s spirit world. They further told us of decades of history or even of successes in a single battle. Objects and visual designs–both Native and European in origin–mattered greatly and variously served as teacher, dealmaker, protector, story teller, archivist, historian, peace maker, and certainly as a conduit to one’s overarching god. While we can never know just how much of the Native symbolic work has been lost, those items that do survive today are housed in Native homes and communities, museum collections, and, sadly, looters’ abodes and with rogue art dealers. The location of these items is controversial in many instances. One can only hope that these treasures receive proper reverence and that many can one day find a home back among their Native communities.

Answer the following questions and/or do the following activities:

- Create your own winter count for the last ten years of your life. What will you draw? What will each icon symbolize?? Do not write words, simply reflect and draw images.

- You are conducting an audit of items that are being gathered for Father Foucault’s 1701 journey to the Arkansas River. What purpose do you think he has for the items listed for his Arkansas Mission? Choose 7 items and prepare your thoughts on their usefulness in terms of relationship, communication, religion, alliance and so on: Powder, lead, balls; black, green, barreled, and white beads; vermillion; hats, shirts and leggings; knives, hatchets, hoes; spices, pepper; soap; signet rings; cotton, thread, gold lace; Spanish wine; pictures of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, St. Joseph, St. Michel, the Guardian Angel; small crucifixes, rosaries, medals; a world map, a painting of the King and Queen,

a map of Paris and other pretty cities.

a map of Paris and other pretty cities. - Examine more thoroughly the winter count of Lone Dog that is housed today in the Museum of Native American History in Bentonville, Arkansas. Analyze the various icons present in conjunction with the chronological descriptions. Describe five icons and indicate how peace, illness, warfare, treaties, or impactful periods of time are drawn based on the chronological text. (Click on the image to the right to see an enlarged version).

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 139-141. ↵

- The Miami-Illinois word is actually "páyiihsa." ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 471. ↵

- Southwest Parks and Monuments Association [herein after SPMA] Petroglyph National Monument (Tucson: Petroglyph National Monument, 1993), 2. ↵

- SPMA, Petroglyph, 5-7. ↵

- George Sabo III, Jerry E. Hilliard, and Leslie C. Walker, “Cosmological Landscapes and Exotic Gods: American Indian Rock Art in Arkansas,” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 25, no. 1 (February 2015): 263. ↵

- Sabo et al., “Cosmological Landscapes,” 264. ↵

- Morris Arnold, “Eighteenth-Century Arkansas Illustrated,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 53, no. 2 (1994): 119–136; Jones, Shattered Cross, 139. ↵

- Thwaites, "Relation of 1666-67," JRAD, vol. 51 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1899), 49. ↵

- Velma Seamster Nieberding, The Quapaws: Those Who Went Downstream (Quapaw, Oklahoma: Quapaw Tribal Council, 1976), 3; Jones, Shattered Cross, 146. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 147-48. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 83; "de Montigny," ASQ, Missions no. 41, p. 15. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 204; George Sabo III, Paths of Our Children: Historic Indians of Arkansas (Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, Popular Series No. 3. 2009), 56-64. ↵

- Havard, Montreal, 1701, 25. ↵

- Havard, Montreal, 1701, 25. ↵

- G. Malcolm Lewis, "Maps, Mapmaking, and Map Use by Native North Americans," in David Woodward and G. Malcolm Lewis, ed., The History of Cartography, Volume 2, Book 3: Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 89. ↵

- James D. Keyser & Phillip Cash, “A Carved Quirt Handle from the Warm Springs Reservation: Northern Plains Biographic Art in the Columbian Plateau,” Plains Anthropologist 47, no. 180 (February, 2002): 56. ↵

- “Très Ancien Règlement du Petit Séminaire de Québec,” ASQ, Manuscrit 239, no. 7. ↵

- “Coutumier du Séminaire, Article Second,” ASQ, Manuscrit no. 239, pp. 112–113. ↵

- Dennis Martin, “Les Collections de Gravures du Séminaire de Québec” (Master’s thesis, Université Laval, 1980), 10; Mgr Amedee Gosselin, “Les Grandes Devotions au Canada 92eme cahier,” ASQ, Manuscrit no. 367, pp. 13–14. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's Second Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 189. ↵

- Thwaites, "Illinois Mission," JRAD, vol. 64 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1900), 229 ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 106. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 145; Margaret J. Leahey, “‘Comment peut un muet prescher l’évangile?’ Jesuit Missionaries and the Native Languages of New France,” French Historical Studies 19, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 123; Thwaites, "Relation of 1668-69,: JRAD, vol. 52 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1899), 118–119. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 146; Tracy Neal Leavelle, “Religion, Encounter, and Community in French and Indian North America” (Ph.D. diss., Arizona State University, 2001), 119; Thwaites, "Illinois Mission," JRAD, vol. 64, 225–237; Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 103. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 146; Leavelle, “Religion,” 120–122; “Mémoire,” ASQ, Missions, no. 107. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 110; Thwaites, "Relation of 1653-54," JRAD, vol. 41 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1899), 165. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 21; Louise Phelps Kellogg, Early Narratives of the Northwest (New York, C. Scribners's sons. 1917), 85, 129; Ruth Lapham Butler, Journal of Paul du Ru [February 1 to May 8, 1700]. Missionary Priest to Louisiana (Chicago: Printed for the Caxton Club, 1934), 18. ↵

- Sabo, "Rituals," 77; Sabo, Paths, 36; Sabo et al., “Cosmological Landscapes,” 261–273. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 148; Tracy Neal Leavelle, The Catholic Calumet: Colonial Conversions in French and Indian North America (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 22. ↵

- Thwaites, "Le Jeune's Relation, 1638," JRAD, vol. 15 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1898), 35. ↵

- Thwaites, "Le Jeune's Relation, 1635," JRAD, vol. 8 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1897), 111-113. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 103. ↵

- Kathleen DuVal, “The Education of Fernando de Leyba: Quapaws and Spaniards on the Border of Empires,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60, no. 1 (Spring 2001): 1; 'Fernando de Leyba to Luis de Unzaga y Amezaga, June 6, 1771, legajo 107, Roll 12, folio 247, Papeles de Cuba, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain. ↵

- DuVal, "Fernando de Leyba" 1. ↵

- DuVal, "Fernando de Leyba," 9-10. ↵

- Joseph Patrick Key, “'Outcasts Upon the World': The Louisiana Purchase and the Quapaws," The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62, no. 3 (Autumn, 2003): 275; John B. Treat to Henry Dearborn, May 20, November 18, 1806, Arkansas Trading Factory Letterbook, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 75, microcopy, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville. ↵

- Margry, "Relation de Joutel," Découvertes, vol. 3, 446. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 198; “Henri Roulleaux De La Vente to unknown,” February 5, 1709, ASQ, Lettres R, no. 86, p. 3. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 200; Thwaites, "Marest to Germon," JRAD, vol. 66 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1900), 263–265. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 129-131. ↵

- Jones, Shattered Cross, 141. ↵

- Sabo, “Rituals," 78–79. ↵

- Demazilliers Letter, June 24, 1770. Papeles de Cuba, Legajo 107, Roll 12, f. 106, Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla. ↵

- Orieta to the Governor, February 20, 1771. Papeles de Cuba, Legajo 107, Roll 12, f. 167, Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla. ↵

- To Governor Luis de Unzaga from Fernando de Leyba, April 6, 1773, Papeles de Cuba, Legajo 107, Roll 12, f. 348, Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla. ↵

- Noémie Etienne, “Transaction and Translation: The Trade in Non-European Artefacts in Paris and Versailles (1750-1800)," in Acquiring Cultures: Histories of World Art on Western Markets, edited by Bénédicte Savoy, and Charlotte Guichard and Christine Howald (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), 21. ↵

- Christian Feest, “First Nations-Royal Collections,” American Indian Art Magazine (Spring 2007): 45. ↵

- Christian Feest, “Royal Robes. Native American Hide Paintings at Versailles in the Eighteenth Century,” Tribal Art Magazine (Summer, 2007): 123. ↵

- Etienne, “Transaction and Translation," 26-27. ↵

- Bibliothèque Municipale (Versailles), and Mois du Patrimoine Écrit, Les Cabinets De Curiosités De La Bibliothèque De Versailles Et Du Lycée Hoche : [Exposition], Versailles, 18 Septembre-27 Novembre [2004], Bibliothèque Municipale. Re-Découvertes, 85. Paris: Fédération française pour la coopération des bibliothèques, des métiers du livre et de la documentation, FFCB, 2004, pp. 77-78. ↵

- Feest, “First Nations,” 46; André Delpuech, Myriam Marrache-Gouraud, Benoît Roux, "Valses d’objets et présence des Amériques dans les collections françaises: des premiers cabinets de curiosités aux musées contemporains," La Licorne et le Bézoard, une histoire des cabinets des curiosités, Gourcuff Gradenigo, pp. 271-316, 2013, 9782353401611. <http://www.gourcuff-gradenigo.com/bezoard.html>. p. 278. ↵

- Feest, “Royal Robes," 123. ↵

- Delpuech et al., "Valses d’objets," 278. ↵

- Bibliothèque, Les Cabinets, 78. ↵

- "Des peaux de bisons décorées par les Indiens sont exposées depuis hier au Musée d'ethnographie," Le Journal, le 14 avril, 1934, 4b. ↵

- Cabinet de Curiosités et d’objets d’art de la Bibliothèque publique de la ville de Versailles: Catalogue (Versailles: Imprimerie de E. Aubert, 1869), 21. ↵