5 Maps and Landmarks

We all use maps, right? Our phones give us instant access to digitized visual information and directions that can take us precisely from one point to the next! We can determine the location of the nearest gas station, the nearest hospital, even road construction or traffic jams. We can print out maps with directions that can help us arrive at our desired location even when out of WIFI range. But if you were to hand-draw a map of a region or route that was important to you today, how would you draw it? What would you include? Words, symbols, a legend? What would be the most significant points to highlight? Why?

Introduction

Native peoples created and used maps on the North American continent for centuries. They drew ephemeral maps in the sand and used twigs or hand gestures to pinpoint locations. They used more tactile devices such as charcoal or paint, even etchings on shells, birch bark, wood, skinned trees or deerskins to develop informative, topological charts and maps. Circles indicated villages, lines indicated connections, but even hieroglyphs and symbols indicated important aspects of the region. In short, Native peoples were rich cartographers who communicated information on locations and relationships, all topological in nature, quite precise and accurate.

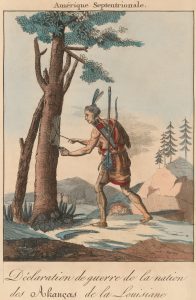

Europeans also created maps, most often to chart terrain so to enhance their understanding of the continent’s geography. Though they primarily used parchment or cotton-based paper with quill pen and ink to create maps, more artistic cartographers such as Benjamin Dumont de Montigny used watercolors to artistically enhance their work. But Europeans did not create maps in a vacuum. They relied upon Native peoples to help pinpoint locations, provide directions, even indicate friend or foe through gestures, signs, and previously created Indigenous maps. Some of these cartographies or topological guides were even collaboratively created–drawn or painted by Native peoples, with French, English or Spanish words added to clarify the visual information. No matter how, when or why one created a map, it communicated cultural and spiritual landmarks, allies and enemies, paths and trails, subsistence opportunities and waterways as needed.

Native Drawn Maps

Native artisans demonstrated exquisite ability to visually display the geographical space that surrounded them–to mark trees to indicate their path, or to delineate boundaries between their terrain and that of others, or even to highlight the European presence.[1] Indeed, the Englishman John Lawson once remarked of Native peoples: “They are expert Travellers, and though they have not the Use of our artificial Compass, yet they understand the North-point exactly, let them be in ever so great a Wilderness.”[2] Father Chretien Le Clercq, a 17th century Recollet priest who served among the Mi’kmaqs of Acadie, witnessed that “they have much ingenuity in drawing upon bark a kind of map which marks exactly all the rivers and streams of a country of which they wish to make a representation. They mark all the places thereon exactly and so well that they make use of them successfully, and an Indian who possesses one makes long voyages without going astray.”[3] Father Joseph François Lafitau, a French Jesuit priest in the early 18th century, described the Iroquois as possessing “an excellent sense (of direction). It is a quality which seems born in them. . . . They go straight where they wish to go, even in uncharted wildernesses and where no paths are marked. On their return, they have observed everything and trace, grossly, on sheets of bark or on the sand, exact maps on which only the marking of degrees is lacking. They even keep some of these geographical maps in their public treasury to consult them at need.”[4] Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, Baron de Lahontan, an early 18th century French explorer, also commented on their cartographic expertise:

“They draw the most exact Maps imaginable of the Countries they’re acquainted with, for there’s nothing wanting in them but the Longitude and Latitude of Places: They set down the True North according to the Pole Star; The Ports, Harbours, Rivers, Creeks and Coasts of the Lakes; the Roads, Mountains, Wood, Marshes, Meadows, etc. counting the distances by Journeys and Half-Journeys of the Warriors and allowing to every journey Five Leagues. These chorographical Maps are drawn upon the Rind of your Birch Tree; and when the Old Men hold a Council about War or Hunting, they’re always sure to consult them.”[5]

No matter the style used, any Native-born maps that survive today help us to understand how Native peoples once communicated information on the landscape in which they resided or traversed. Indeed, Native communities had a strong understanding of their center. Among the Quapaws, their village was laid out in a North/South and East/West fashion, enveloped by earth and sky. They, like the Tunicas, the Natchez, the Osages and many other Native communities, had a central plaza which was the gathering place for all ceremonies. The drum placed in the center of this plaza literally served as the heartbeat of the people. Among the Choctaws, one could stand in the center of their plaza, face the rising sun, and acknowledge “the four directions and the four corners of the universe” that infiltrated the architectural layout of their community as well as their ceremonies and rituals. But as with the Quapaws, the concept of the “sky dome” or “celestial vault” provided “a shelter for this two-dimensional system and is incorporated into the building symbolism of many groups, often with complex astronomical allusions.” That is, while four directions were horizontal, the sky and earth created a “vertical axis, the zenith and the nadir, adding two more directions to the four cardinal ones, plus a seventh-the center on which one stands.”[6]

The Skidi band of the Pawnees developed a celestial map–the Pawnee star map–that shows the spatial arrangement of their villages based on cartographic principles. Prior to removal to the Oklahoma territory, the Skidi Pawnees were divided into five villages. Each community had a different sacred shrine that contained important elements based on a specific star, the name of which was applied to the shrine and village. Ultimately, the star map portrayed the villages and their shrines based on the relative positions of the stars in the sky. Indeed, the Big Dipper was hallowed by many Native nations including the Crow who called it “the Seven Brothers,” or the “Seven Star Persons,” or even “the Seven Buffalo Bulls,” any of which identified the Big Dipper as “‘pipe-pointer’ stars to guide Crow war parties at night.” For the Pawnees, the Crows and many others, the connection between particular stars and constellations with villages and sacred sites on earth rendered the night sky a veritable map of their earth landscape.[7]

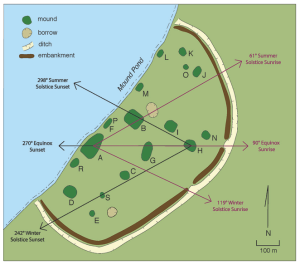

Closer to home, the Plum Bayou Mounds located to the east of Little Rock, Arkansas are laid out in a form of a celestial map themselves. As Martha Ann Rolingson, former archeologist of this important archeological site wrote:

“Some mounds were placed to line up with each other and with the positions of the sun on the horizon at sunrise and sunset on the solstices and equinoxes. A person standing on Mound A saw the sun rise over Mound B on the summer solstice, June 21, and over Mound H on the equinoxes, March 21 and September 21. Standing on Mound H, an observer saw the sun set over Mound B at summer solstice and over Mound A on the equinoxes. From Mound E, the north star could be seen directly above Mound A. The position of the sun on the horizon changes throughout the year. A person watching the sunrise or sunset can observe these changes, and use them to mark the seasons and to schedule activities such as planting crops and holding ceremonies.”[8]

Native-drawn maps were often meant for a nation alone, to fulfill any immediate needs within a family or a community. These maps might be used to plan raids, support spiritual activities or to communicate with each other during hunting ventures. Oftentimes, these maps were treated as ephemera, worthy of immediate or timely use but not long-term preservation. For example, when Jacques Cartier made his way through the St. Lawrence River Valley, local Native peoples showed him the course of the river “’with certaine little stickes which they layde upon the ground in a certaine distance, and afterwards layde other small branches between both representing the Saults.’” Likely those “certaine little stickes” represented the three Lachine Rapids which were seen by Cartier from a distance once on a hill rise at Hochelaga.[9] Over one hundred and fifty years later, as LaSalle’s survivors tried to make their way to the Mississippi River from Texas, Henri Joutel wrote of how they were “informed by one of the Indians that we were not far from a great River, which he described with a Stick on the Sand and shew’d it had two branches, at the same time pronouncing the word Cappa, which as I have said is a nation [The Quapaws] near the Mississippi.”[10] And even through a hand gesture, Aikon Aushabuc, a Mi’kmaq chief, created a map through the use of an almost complete circle with his thumb and index finger. With this shape, he equated joints along his hand circle with New York, Boston and Halifax, Québec and Montréal. The incompleteness of the circle allowed him to show the location of his community, Pookmoosh, to indicate that “the Indians would soon be surrounded, which he signified by closing his finger and thumb.”[11]

While most maps and geographical indicators created by Native peoples are long gone, a few do remain and provide a glimpse into the various Native cultures present at the time and the land that surrounded them. Though many that survive are protected by Native peoples so as to maintain the sacredness of such artifacts and their related ceremonies, others are available for study and discussion including the following examples from a variety of Native cultures across North America.

Within the Great Plains, a number of structures of pre- or protohistoric origin referred to as “medicine wheels” survive today. These manmade structures consist of a central small circle or cairn of stones. Lines of stones of unequal length radiate out from this central point with some terminating into smaller stone cairns. Though there is some debate as to the purpose of these ancient sites, some believe that cartographic principles are at work. In particular, one common theory is that cairn structures were memorials, meant to commemorate war exploits of great chiefs. As such, the stone lines “show the directions of each expedition, their lengths, the relative distances covered, and the presence or absence of distal cairns at the end tells whether any of the enemy were killed.”[12] The research, however, continues.

While a medicine wheel may indicate directions to victory, the ability to actually map out an entire landscape called on tremendous knowledge and skills that few could attain. Amos Bad Heart Bull, an Oglala Sioux, was a prolific artist who created over 400 artworks. A cousin of Crazy Horse, Amos served as a scout for the U.S. army in 1890. Sometime between 1891 and 1913, he created a rather precise regional map on which he drew important elements of the nation’s Black Hills terrain and surrounding plains including Bear Butte, Ghost Butte, Old Baldy, and Bear Lodge Butte. Surrounding this region, he drew drainage networks, some 30,000 square miles worth, but with remarkable accuracy. A striking strength of this map is that today, Bull’s drawing can be seen from satellite imagery. That is, with his own map superimposed onto an image of the region from space, one can see the exactness of his understanding of the geographical layout of his peoples’ terrain.

For that matter, a Native community could use an entire landscape to “map” or chart its world view. Several Arkansas archeologists–George Sabo, Jerry Hilliard and Leslie Walker–examined rock art within the Arkansas River Valley that creates a landscape of topological significance.[13] The Arkansas River, which flows west to east, divides the valley into north and south mountainous areas. The rock art found within this region dates between 1500 and 1700 and is distributed in a particular spatial pattern with symbols referencing the spirit world located predominantly on the north side of the river, and symbols of the earthly world observable on the south side of the river. Rock art displayed on the south side, within the boundaries of Petit Jean Mountain, includes naturalistic and observable images of plants, animals, people, ceremonial objects and sunbursts as well as various abstract and geometric symbols (nested diamonds, spirals, squares). Rock art displayed on the north side includes not only abstract and geometric figures but also imagery “based on imagined spirit world prototypes reflecting cosmological themes.”[14] One example is the “headless anthropomorphic image” that seems to represent a culture hero named “Morning Star” or “Red Horn” who “provides a charter for celebrating the victory of life over death via propagation of a long line of descendants.”[15] Another spirit-oriented symbol is that of the hellgrammite or dobsonfly larva. This insect has a distinct life cycle that associates the three world realms–sky, earth and water. “Adults lay eggs on tree branches that hatch into larvae and fall into streams where they feed and grow until they crawl back onto the land and enshroud themselves within a chrysalis, later to emerge as winged adults.” As such, this insect is “capable of crossing from one ‘world’ to another as it navigates transitions from one form or state to another.”[16]

The distribution of these symbols on the north and south sides of the Arkansas River very much replicates the belief system, certain traditional rituals, and the village architecture of such Dhegihan Siouan speaking tribes as the Quapaws and the Osages.[17] Thus, the artists used the landscape to draw a map representative of their cultural lifeway pattern whereby “Sky People clans responsible for the ritual maintenance of community relations with the spirit world reside on the north side of the village [or river], and Earth People clans responsible for the ritual maintenance of material welfare reside on the south.”[18]

Two other variations of landscape “mapping” can be seen as well, one through the rock art that remains on open face shelters and caves the other based on a Spanish map. To the former, in the state of Tennessee, Native peoples used the landscape to provide a spatial representation of their world view within the Cumberland Plateau. With petroglyphs and pictographs on open air rock sites and similar styles of rock art within caves, along with a variation in colors used and figures drawn, the researchers have shown that there is a distinct spatial organization in play throughout this landscape that builds a relationship between upper world and lower world spiritual entities. This was intentional with sites most often facing due south. Consequently, these researchers suggest “that bluffs and caves were selected for art production depending on celestial and/or solar exposure.”[19] Within these landscape structures, “‘the lower world’ was a world of darkness and danger and was associated with death, transformation and renewal; there were a number of characters associated with this world, including supernatural serpents, dogs that accompanied dead humans on the path of souls and a seminal ‘earth spirit’ who was involved in making and unmaking the world. This layered universe was a stage for a variety of actors that included heroes (‘Birdman’, ‘Morningstar’), monsters (the giant serpent ‘Uktena’), and creatures that could cross between these levels (fish, frogs, birds, bats, waps etc.).” Alternatively, the open bluffs were above the caves where art was found. Thus, “upper world imagery was vertically segregated from lower world imagery. When colour is involved, upper sites tend to be red, a colour associated with life and renewal among native south-eastern peoples, while lower sites tend to be black, a colour associated with death.” Ultimately, “the cosmological divisions of the universe were mapped onto the physical landscape using the relief of the Cumberland Plateau as a topographic canvas,” much like the Native peoples made theirs along the Arkansas River, albeit horizontal in focus rather than vertical.[20]

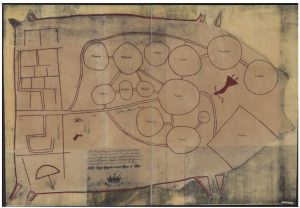

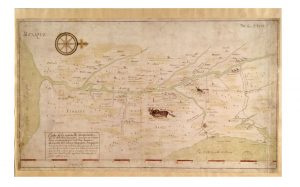

Alternatively, a European drawn map, a topic to which we will turn more deeply momentarily, signifies how the Caddos used their own terrain to mark Caddoan Cosmology. The Téran Map, drawn by Domingo Terán de los Ríos in a 1691-1692 expedition, portrays the layout of a Caddoan settlement along the Red River. The map itself shows the layout of a community with individual farmsteads, the central location of the community’s leader as well as a temple mound center. Arkansas archeologist George Sabo suggests that this map “reflects key elements of Caddo beliefs about their relations with the spirit world…that the Terán map represents a cosmogram embedded in the layout of the depicted community.”[21] The farm settlements found throughout the map contain single or multiple dwellings with beehive roofs typical of the Caddo as well as open platforms and storage platforms. These hamlets serve to feed the population with agricultural products while also appeasing spirits with sacrifices at times of harvest. To the far left is a large structure, a temple built both upon and into a mound with the word “temple” written above. In the middle of the map is a dwelling that houses the caddi, the community leader of this Caddoan group. The word Cadi is written below the larger dwelling. Posts are also present as is a cross and what appears to be a European structure, likely indicative that the Spanish, who drew this map, resided near the Cadi for a period of time before moving on, for no mission was established at this location.

So how does this map represent Caddo cosmology and social organization? As with much of what we’ve seen previously in this text, part of the Caddoan world view was to “maintain an order based on reciprocal or balanced relationships between This World and the spirit realm,” with reciprocity “something requiring active maintenance.”[22] Thus, community members worked to support the Cadi while the Cadi in turn worked to maintain reciprocal relationships with community members. Alternatively, the spiritual leader, the Xinesi, worked “to maintain reciprocal relations between the human community and spirit beings populating the Above and Below World realms.”[23] As the highest ranking member of the community, the Cadi is purposely placed at the center to serve as the central source between the earthly realm and the spiritual realm. Alternatively, the spiritual leader oversees the temple, the gateway to the spiritual realm. That is, with the temple on the edge of the community, it serves as a “gateway,” both when “Caddo leaders typically marched out in procession to receive visiting dignitaries, who then were carried to the temple where they were welcomed with ceremonies…,” or as a place in which the community members “worshipped and made offerings to their gods,” thus an additional gateway between the community’s spiritual and human realm.[24]

Opposite such large landscape mapping, Native peoples also used tree bark or peeled trees to “map” their terrain. Red ocher, charcoal or other trade colors mixed with bear grease helped to highlight particular cartographic elements.[25] For example, as Sieur de LaSalle, Jean Cavelier and Henri Joutel made their trek eastward toward the Mississippi River from the failed French colony in Texas, they spent some time among the Cenis near the head of the Neches River in modern day east Texas. Jean Cavelier wrote, “While we tarried there five or six days, the Indians made a very exact map of the neighboring rivers and nations [using bark and a piece of coal]. They told us that they knew the Spaniards, and depicted to us their clothing, etc. It is clear that if we had understood their language, we could have learned the real distance between this village and the Spaniards. It is to be believed, however, that these are not far off, since the Indians have a great number of good horses.”[26] And when Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville entered the mouth of the Mississippi for the first time in the spring of 1699, he too mentioned the use of Native drawn maps. Unsure of his whereabouts at the time, both the Bayougoulas and the Mougoulachas drew regional maps for the French Canadian explorer. Iberville needed to understand his current location’s connection to the Gulf waters; he needed to determine his ability to travel inland to the French settlements in the Illinois region. He showed the Native peoples printed maps, made during LaSalle and de Tonti’s previous journey to the gulf, hoping to confirm the presence of a reported fork upstream, wanting also to learn of the Mississippi River’s tributaries. To assist Iberville, one Native person drew “a map on which he indicated that during the third day of our journey, we shall encounter a river on the left bank, called the Tassénocogoula [Red River], which has two branches. Eight villages, which he named … are situated along the western tributary.” Ultimately, Iberville relied on Native cartographers to better understand the Mississippi, to verify his position, and to understand the connections between the south and the French settlements farther north so to help deter invasions by the Carolina English, among other things.[27]

One also peeled the bark from a tree and then painted or drew upon the exposed wood so to mark terrain, declare war or provide messages to those who passed by. But even a wampum belt, often used for treaties and accords, could symbolize “both geopolitical and spatial relationships.”[28] The earliest reference to a wampum belt as a map (symbolic, metaphorical and referential) stems from Father François Le Mercier in the early 1650s. In a council between the Iroquois and the Algonquians at Sillery, Québec, a participant stretched out a wampum belt in the middle of the room, stating: “Behold the route that you must take to come and visit your friends. [There] are the lakes, there the rivers, there the mountains and valleys that must be passed; and there are the portages and waterfalls. Note everything, to the end that, in the visits that we shall pay one another, no one may get lost.”[29] One hundred years later, a Cherokee Captain presented a similar, figurative “road belt” to the Iroquois: “He took out a Belt of Nine Rows, with Three Figures of Men wrought in it, one at each End and one in the middle, and a Row of black from one End to the other.” As he spoke to the Iroquois, he said “We have made a Road for you, and we will endeavour to keep that Road clear for our Brothers to walk in, in hopes that you will come and make use of that Road; but if any of the Children of the French make use of our Road, or throw any obstructions in the Way we will certainly kill them.”[30]

Native-Drawn Maps Infiltrated by European Language

Native peoples sometimes created maps only to be written upon by Europeans to help the latter better understand the region’s terrain and peoples. That is, while a map itself made perfect sense to the Native peoples because of its topological nature (paths to and from waterways, villages, and so on), Europeans demanded more accuracy, since “imagery alone was not wholly sufficient” for Europeans.[31] They needed to identify villages, waterways, mountain ranges, landmarks and the like by name. Words had to be written onto the map to make it more comprehensible to current and future European readers who otherwise were illiterate to the symbolism and information communicated within Native-drawn maps. But even when words were applied, Native peoples did not provide distances since they viewed them as “experiential itinerary measures; days’ journeys, overnight stops, distances between pauses, the distance over which a gunshot could be heard,” influenced by the “season of the year, environmental conditions, mode and purpose of travel, physique and skills of the weakest member or horse, and previous experience of the route.”[32] Distance and days’ journey could not be easily conveyed to the satisfaction of the European mindset.

But what of the word “map”? Was this term used by Native peoples during the colonial period? Certainly, as the Indigenous, Europeans and Americans interacted more and more, creative forms of the word “map” did appear but varied from nation to nation. The Cheyenne, for example used the term Ho’eva-ho’xe’esto which stems from two nouns that mean “land” and “paper.”[33] The Chickasaw term for map is just as complex–yakni isht ulhpisa holisso–which literally means “paper earth measure.” As for the Cherokee, their term–elohi datlilostanv—literally means “earth picture.” Not surprisingly, some nations simply did not have a word for map. But even when words were created for the physical item, Native peoples did not solely rely upon them for information in the same manner as did the French. The Apache, Nick Thompson, put it best: “White men need paper maps…we have maps in our minds.”[34]

Miguel and his Texas Map

The earliest known map drawn by a Native person on the North American continent and then added to by Europeans is that of Miguel who created a map of the Great Plains on April 29th, 1602. Specifically, the Spanish asked Miguel to “mark with pen and ink on a sheet of paper … the pueblos of his land. Miguel proceeded to mark on the paper some circles resembling the letter “O”…Then he drew lines, some snakelike and others straight, and indicated by signs that they were rivers and roads.”[35] The map itself, today housed in the Archives of Seville, includes clarifying words written by the Spanish that assisted them as they explored the region from New Mexico into the Arkansas River Valley.

Quapaw Three Villages Robe

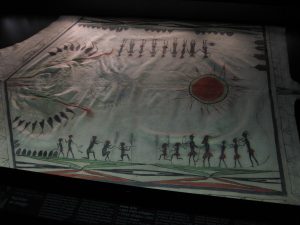

In a more artistic fashion, the Quapaws of Arkansas created a painted robe on deerskin that portrays the location of three of their villages. While we discussed this as an art form in Chapter 3, here we take on a cartographic study, for once the robe was completed, a Frenchman placed on the deerskin the words “Ackansas, Ouzovtovovi, Tovarimon, and Ovoappa,” thereby turning this magnificent masterpiece into an artistic map.[36] Otherwise known as Osotouy, Tourima and Kappa, these village names represent three of the four villages known to have been along or near the Arkansas River in the 17th and 18th centuries. The one village absent is Tonguinga which consolidated with Tourima by 1727, thus giving some indication as to when this robe may have been painted. (Some early historical documents suggest a fifth Quapaw town, Imaha.)

From a topological standpoint, this robe shows the three villages as well as French houses located nearby. These four European-style structures represent Arkansas Post and, as luck would have it, are reflected in the historical record. In 1732, Pierre Petit de Coulange built a military establishment at Arkansas Post to help combat attacks by the Chickasaws on the Quapaws. A 1734 description of the location highlighted four structures–a barracks, a powder magazine, a dwelling house with a fireplace, and a prison, all built in the French tradition with vertical beams.[37] As Morris Arnold describes it, “this almost eerie correspondence would seem to exceed the bounds of mere coincidence, especially since no other eighteenth-century Arkansas military establishment of which we have a detailed account so exactly matches this description.”[38] Thus, this Quapaw-drawn robe could be considered a realistic, topological drawing of the Quapaw villages and French Arkansas Post in the 1730s and 1740s. But Arnold nevertheless posits a challenge in terms of its geographical accuracy. As he states:

“A troublesome embarrassment in the way of a completely confident reading of the skin is that the order in which the Quapaw villages are arranged on it does not correspond with any known configuration for them in the eighteenth century. The sources for the 1730s are in unequivocal agreement that the first village encountered on the Arkansas River on the way up to the Arkansas Post was Tourima (with Tonguinga), followed by Osotouy, and then Kappa, this last directly across from the Post. The skin, on the other hand, has Kappa farthest away from the French settlement. It is possible, since the names of the villages may have been added sometime after the skin was painted, that a mistake was made when they were affixed….It is also possible that the skin deals with a time after 1748, when, on account of flooding, the Quapaws moved their villages above the fort to Écore Rouges. There is no record of exactly where the Quapaws were located at that time, nor do we know the order in which they arranged themselves on that river.”[39]

Regardless of this challenge, “if one takes a rather generous view of the amount of cartographic content that it takes for an object to be a map, this skin would be the oldest known original [Mississippi] Indian map extant.”[40]

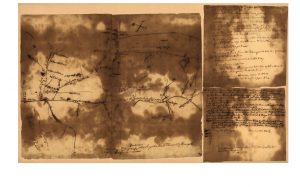

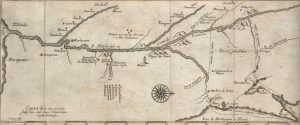

Mississippi River in 1699

Near in location but earlier in timeframe to the Quapaw robe are two maps that may have been drawn by Native peoples and then written on by French Missionaries from the Séminaire de Québec sometime between 1699 and 1700.[41] These very simplistic maps show the Mississippi River and its most significant tributaries with Indian nations indicated along the different waterways. Upside down U’s as seen on page 1 and page 2 of one of these maps further indicate the number of associated villages for a given nation. Most likely, Native peoples told the European inscriber the names of the various nations along these different waterways since, other than the lower waters of the Yazoo and the Arkansas, the Seminary missionaries did not initially explore the tributaries out from the Mississippi. With time, others who later created more sophisticated maps confirmed the presence of these villages and nations.

The Catawba/Cherokee Map

One of the more impressive dually-created maps that we can explore and understand with the help of the historical record and a Native creation story is the Catawba or Cherokee Map. This map is rather perplexing in and of itself. Drawn by a Native person, some say a Catawba, others say a Cherokee, this map focuses on relationships between Native nations and the English in the southeastern part of North America.

By 1720, Carolina was declared a royal colony. Francis Nicholson, its first Governor, was subsequently charged to establish forts “toward the inland frontiers” so as to protect the region from the French and to cultivate “a good understanding…among the Cherokee Indians.” As a part of this, Nicholson was to ensure that a map provided the “exact description of the whole province.”[42] Consequently, this 1721 deerskin map highlighted the locations of the various nations in the region between Charleston and Virginia. “Copyed from a Draught Drawn & Painted upon a Deer Skin by an Indian Cacique and Presented to Francis Nicholson Esqr. Governour of South Carolina,” the map itself is in a deerskin shape, with deer hoofs at its corners, and marked with red and black ink.[43] Both Virginia and Charles Town (Charleston), South Carolina are represented as are numerous Native communities including the Cherokees and the Chickasaws, frequenters of the Mississippi River. Paths are indicated by straight columns between certain villages and the English settlements. Three figures are also portrayed on the map–an armed man, a deer, and a woman.

Some have claimed that this map was created by the Catawbas, perhaps the headman of one Catawba tribe, the Nasaws, since they are centrally located on the map within the largest circle, with paths leading to associated Catawba villages.[44] This centralization suggests that the Catawbas were key in the trade effort of the 18th century. Note in particular the path from Charles Town towards the Catawba villages, through them and out into other villages as well as on into Virginia. This particular pattern “shows a conscious highlighting of the importance of the mapmaker’s own tribe in relation to the developing British colonies, while the two non-Catawba nations, the Chickasaw and the Cherokee, are peripherally located in the upper right of the map.”[45]

Though attributed to the Catawbas, Ian Chambers suggests that this map was actually drawn by a Cherokee. In the early 18th century, Charles Town, South Carolina was considered the most important Indian trade hub in the English colonies. It maintained a trade route that extended some 1000 miles towards the west and provided an average of 54,000 deerskins to England by 1715. But such trade was not without its challenges, as pressures from the Virginians to the north impacted trade in and out of Charles Town. Indeed, by 1715, a conflict arose–the Yamasee War–whereby several Native communities rose up against the town. By 1716, trade in deerskins had dropped from 54,000 to 4,700 a year.[46]

Chambers suggests that “a Cherokee mapmaker, anxious to highlight the impediment that the Catawba had brought to the Cherokee-Carolina trade” created this map. Utilizing historical documentation to support his claims, Chambers argues that the Cherokees originally engaged in trade with Virginia, but no longer did so by the time of this map’s creation. A delegation of Cherokees went to Williamsburg, Virginia and declared “that their Nation observing ye Factors of the late [Virginia] Indian Company had totally withdrawn their Effects out of their Country, by wch [sic] they [the Cherokee] were apprehensive they shou’d have no further Trade wth [sic] this Colony.”[47] With the loss of contact with Virginia, the Cherokees needed a trading partner to maintain their acquisition of European goods. South Carolina was their best hope. But on the current trail followed, they had to pass through the Congaree fortress where the Catawbas were welcomed, not the Cherokees: “The Cattawbas was admitted into the Fort and had Regress and Fregress when they pleas’d as their own familiar, and their coming in orders were given to get them some victuals to eat, while the Charikees were almost starv’d for want of it.” The current map shows that the Cherokees who promised to “make a new path,” forego entrance into the Catawba region. The trail immediately branches off from the Catawba path so as to reach the Cherokee nation and from there does not include any path to the Virginia region. Thus, the Catwaba were prominently displayed in the center of the map to show that they were a great obstacle towards Cherokee/Charles Town trade.[48]

Aside from the historical record, Chambers also focuses on a Cherokee creation story to explain the drawn figures of the woman, the man and the deer on this map:

“After the world had emerged from the primeval waters and the first man and woman had been taught how to gather the food provided in abundance, sin came into the world through the disobedience of the couple’s children. The children had spied on their parents to see from where came the corn, animals and fowl their parents brought home as food. They saw how their father went to a cave and removed the great stone that blocked its entrance before calling to a deer resting nearby, which he picked up and took home. They also saw how their mother entered a small cabin, placed a basket on the ground and, standing over it, jumped up and down until large ears of corn began to fall into it.”[49]

The man, Kana’tĭ, is known as the hunter father. The woman, Selu, is the corn mother. Placing her near the Cherokee village is significant, for in the Cherokee creation story, the children saw Selu dancing about, decided that she was a witch, and sought to kill her. “Instantly aware of their intention, Selu tells them that after they have killed her, they were to clear a large piece of ground in front of the house and drag her body seven times around the circle.” Thus her placement on the map “acknowledges her role as the person who remained in the village at all times and who controlled Cherokee domestic life.” As for Kana’tĭ, his placement near Charles Town distinguishes his responsibility for external relations for the Cherokee nation. Being near Charles Town and not Virginia strongly suggests “that the Cherokee were using the map to highlight the benefits of trade between Charles Town and themselves.”[50]

Chickasaw Maps

Closer to the colonial Mississippi, the Chickasaw Maps of the late 1730s, again originally Native drawn and European enhanced, show the distribution and intertribal relationship of the Chickasaw Villages and other neighboring nations in preparation for the French and Chickasaw Wars.[51] The first map dated 1737 was originally drawn on deerskin by the Captain of Pakana, an Alabama war leader and French emissary to the Chickasaws in 1737. Alexandre de Batz, a French architect and draftsman, drew transcripts of this and the second map that follows. This first map, “Plan et Scituation des Villages Tchikachas,” highlights the locations of ten Chickasaw villages, a Natchez village, pathways between them, and routes taken by the French, as well as their encampment from their earlier attack on the Chickasaws in 1736. Much like the Catawba or Cherokee map cited earlier, this map contains circles to indicate villages, straight lines to indicate paths, and other points of reference including squares to signify fields. Larger circles indicate more densely populated villages such as Ogoula Tchetoka where Mingo Ouma, the Chickasaw leader, once lived. The smaller circle labeled with the letter N represents a village of the Natchez who were under the protection of the Chickasaw during this time.[52]

The second map, “Nations Amies et Ennemies des Tchikachas,” also transcribed by de Batz in 1737, is attributed to Mingo Ouma, the Chickasaw leader mentioned earlier who drew this map to highlight his nation’s friends and enemies. Unlike the previous map, this one is far more detailed in scope. Each circle represents a village. Those in red (Mobile and the French, the Choctaws, the Quapaws, the Iroquois, and the Tamarois) were considered enemies, while those drawn in black (the Cherokees and the Alabamas) were considered allies. The center circle, L, represents the Chickasaw nation. The border surrounding this circle is shaded in red to represent blood. Thus, the center is white “because they claim that only good words come from their village, but those of the surrounding country lose their minds by not listening to them at all, and this stains their lands with blood.” Lines emanating out from Circle L represent warpaths to the different enemy circles drawn in red. These particular war paths do not actually meet up with the enemy villages so as to hopefully make peace with them one day. S paths lead to allies, T paths represent war paths between villages, and V paths represent hunting routes. Overall, this Chickasaw map represents a large expanse of territory quite literally from the Great Lakes down the Mississippi River to the Gulf Coast and even over to the Carolinas.[53]

Chegeree Map

The Chegeree map of 1755 also covers a large area that extends from the Middle Mississippi to modern day western Pennsylvania, from Lake Erie to the mouth of the Ohio River. This particular map was likely drawn during the 18th century for a British officer by Chegeree, a Miami man, who lived in the region of the Maumee and Wabash Rivers during the early phase of the French and Indian war (1754-63). The map highlights the location of the Miamis as well as other Native nations allied with the French along the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers.[54] It also reveals the coverage and strength of French forces in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys at the start of the war. Most certainly, this type of information was fundamental to supporting British forces as they and the French fought for control of the mid-North American region.[55]

Native Informed Maps Drawn by Europeans

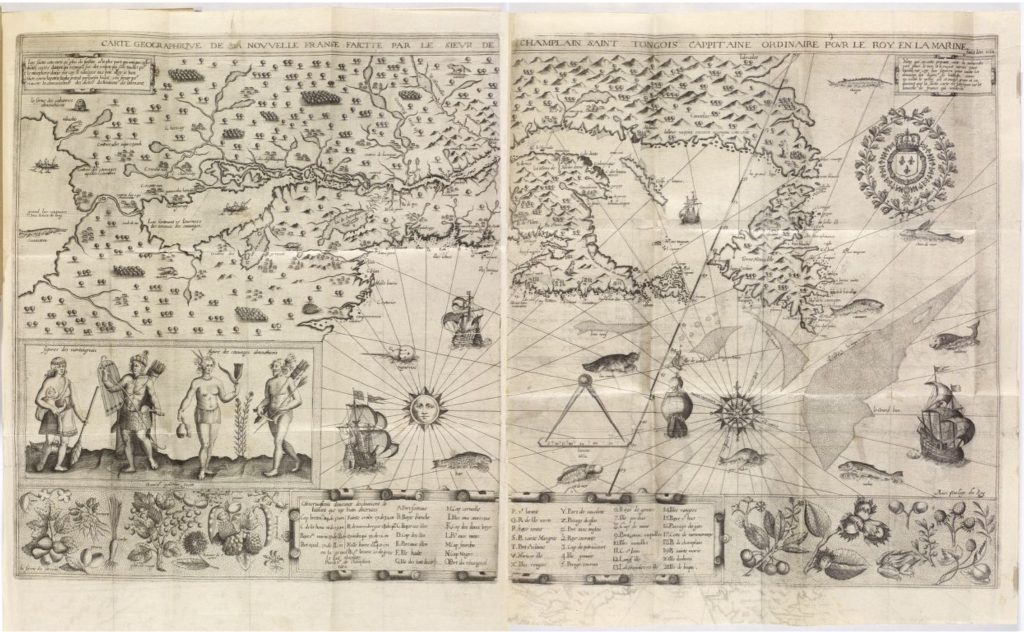

Beyond maps that Native peoples created for themselves, or that were Native created and then enhanced by Europeans, are the maps that were created by Europeans through knowledge communicated to them by Native peoples. Within New France,Samuel de Champlain, a tremendously gifted cartographer in his own right, relied on Native peoples for geographical information to enhance his maps:

“I had much conversation with them regarding the source of the great river [St. Lawrence] and about their [Huron] country, as to which they gave me many particulars, as well as of the rivers, falls, lakes, and lands, and of the tribes who inhabit it, and what is found there. Four of them assured me that they had seen a sea, far from their country, but that the way to it was difficult, both on account of wars and of the wild stretches to be crossed in order to reach it. They told me also that during the preceding winter some [Indians] had come from the direction of Florida, beyond the country of the Iroquois, who lived in sight of our ocean, and friendly terms with these latter Indians. In short they spoke to me of these things in great detail, showing me by pictures all the places they had visited, taking pleasure in telling me about all these things. And as for me, I did not get tired of listening to them, to find out from them some things that I had been in doubt about.”[56]

By 1612, Champlain produced a map of New France that included places he had not yet seen such as Lake Ontario and Niagara Falls. Native Algonquians provided Champlain with their own sketches of the area which bolstered his ability to develop his earlier map. Some four years later, he also mapped Lakes Michigan, Huron, and Superior again relying on details provided by the Hurons and Ottawas so as to enhance the regional information on his map.[57]

Several decades after Champlain’s cartographic efforts, the Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette and his companion Louis Jolliet remarked that their own map that they relied upon to descend the Mississippi stemmed from narratives of the Native peoples they encountered: “We obtained all the Information that we could from the [Native peoples] who had frequented those regions; and we even traced out from their reports a Map of the whole of that New country; on it we indicated the rivers which we were to navigate, the names of the peoples and of the places through which we were to pass, the Course of the great River, and the direction we were to follow when we reached it.”[58]

Take a close look at the hand drawn map of Marquette’s ventures south to the Arkansas River and an additional map that was begun by the Jesuits and added to by Marquette. What do you notice? What was likely unseen by the French at this time? What information do you believe was provided by the Native peoples? What questions do you have about the information provided on these maps?

The Anglican priest, Lawrence Vanden Bosh also drew a rough map with support from Native peoples. According to information provided on his 1694 map of the Lower Mississippi Valley, the geographical layout on the left bank of the Mississippi had been obtained “from a French Indian.”[59] The map itself contains historical comments in English such as an indication of LaSalle’s death in the 1680s, the location of the Spanish and several Native communities to the west of the Mississippi.

And still other maps, drawn by Europeans, could not be completed if the artist was not aware of cultural points of importance within a village. Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, a prolific artist along the Mississippi, often drew Native peoples, their musical instruments and war implements, various animals, as well as Native villages. The great Tunica village that was located near modern-day Angola, Louisiana, is but one example drawn by Dumont de Montigny that includes the distinct layout of the town–the plaza, striking pole and temple–as well as the location of the French nearby. A map of the Natchez concession also shows the location of the French prior to the Natchez revolt of 1729. On this map, once can see the palisade surrounding the Natchez Chief and his sister, their sacred temple, a cross planted by the French, as well as other villages and homesteads scattered about the region.

At times, Frenchmen provided cartographical information to those back in France who drew maps of the North American continent, sites unseen. Father Balthazar de Boutteville, a Seminary priest on the Mississippi, assisted cartographers Claude and Guillaume DeLisle to more precisely develop their maps of Louisiana after 1703. In an interview with Claude DeLisle on January 20, 1704, Boutteville clarified such things as the precise location of the Fort at Mobile, the quality of the soil surrounding this fortress, a more accurate length of the Tunica River, the location of the Ouachas to the west of the mouth of the Mississippi, the placement of the village of Pimitéoui between the Tamarois and Chicago, three forks of the Oubaches, even a fork above Lake Ponchartrain, to the south of the Houmas.[60]

What’s In a Place Name?

Maps communicated location, but place names also provided information on particular points of the landscape. Indeed, Keith Basso’s article “Wisdom Sits in Places,” demonstrates that “wherever one journeys in the country of the past, instructive places abound,” and are identified by name.[61] That is, place names could denote meaning, communicate experiences, even reflect a learning opportunity for those who had perhaps “gone astray.” Among the Apaches, one Charles Henry said this about naming locations among his ancestors:

“They came to this country long ago, our ancestors did. They hadn’t seen it before, they knew nothing about it. Everything was unfamiliar to them. They were very poor. They had few possessions and surviving was difficult for them. They were looking for a good place to settle, a safe place without enemies. They were searching. They were traveling all over, stopping here and there, noticing everything, looking at the land. They knew nothing about it and didn’t know what they would find. None of these places had names then, none of them did, and as the people went about they thought about this. ‘How shall we speak about this land?’ they said. ‘How shall we speak about where we have been and where we want to go?’ Now they are coming!… ‘This looks like a good place,’ they are saying to each other. Now they are noticing the plants that live around here. ‘Some of these plants are unknown to us. Maybe they are good for something. Maybe they are useful as medicines.’ Now they are saying, ‘This is a good place for hunting. Deer and turkey come here to eat and drink. We can wait for them here, hidden close by.’ They are saying that. They are noticing everything and talking about it together. They like what they see about this place. They are excited! Now their leader is thinking, ‘This place may help us survive. If we settle in this country, we must be able to speak about this place and remember it clearly and well. We must give it a name.’”

And so it went. When a particular point was encountered or experienced, a permanent name was assigned to that location. In this specific instance, the people named the described location “Water Lies with Mud in an Open Container.” As a result, “Now they could speak about it and remember it clearly and well. Now they had a picture they could carry in their minds. You can see for yourself. It looks like its name.”[62]

Unfortunately, many place names lost their visual identity with the passage of time. Springs perhaps dried up, riverbeds changed course, buildings replaced landforms, each removing a landmark and its Native identity. Thankfully, the historical record does maintain some names and identities from the past. When the Quapaws were forced from their lands towards the Red River and Caddo country, Antoine Barraqué accompanied them and documented several locations along their journey. For one, they crossed Wattishka Inka, or Saline Bayou. As they went along, they came upon another location called Pasta Waditte, or “Clay of the Scratchy Nose.” Other locations were identified in Quapaw language including: Ente Nompa Wattishka, or Bayou of Swamps and Wass Jinka or Bayou of the Little Bear. So too did one of the most important spots in all of America have a particular name assigned to it by the Native peoples. Hot Springs, Arkansas was long known as Man-a-tak-a or Place of Peace. At this sacred source of healing, Native peoples believed that the Great Spirit resided within the water. Consequently, “an unwritten law of immunity prevailed, for fear strife would drive the Great Spirit away. Those Indians going to the springs were easily identified by ‘the manner of wearing the hair–a manner common to all Tribes and conformed to by all candidates for the benefits of the bath.’”[63] The Choctaws had their own name for New Orleans–Balabanjer, “the town of strangers” to show “acceptance of the presence of the French, even though they considered them to be outsiders.”[64] And among the many Choctaw villages found upriver from the French settlement of Mobile, one was known as Mongoulacha, a Choctaw word that meant “our friends who are there” (nos amis qui sont là).[65]

But Frenchmen also assigned names to particular locations. Near the Mississippi River, Thomas Nuttall recorded a place name–“Ville de Grand Barbe [the Village of Long Beard]”–which the French gave to a village where, contrary to Native custom, the late chief was known to wear a long beard.[66] Still other names highlighted culturally important sites and institutions. For example, in the Ouachita basin, the fur trade was regulated with “informal rules.” That is, Frenchmen and Native peoples hid their collected furs along the river in what the French called “caches,” or hiding places. Though the skins could sometimes be seen from the river “tied to, or laid across poles,” these caches were considered “sacred and rarely stolen.” At some sites, one carved his identity into a peeled tree to communicate dependence on others’ trust, honesty and peace: “The bark was taken off a cypress tree about breast high, for about 18 inches, & two thirds round it, & on the bare place was painted black in a rude manner, the figure of a person on horseback with one hand extended to the water & the other towards the woods, two other persons whose figures were a little defaced seemed to be shaking hands, one of whom had a round hat on: on both sides of these persons were the figures of about a dozen large & small four footed animals apparently feeding, something like deer without horns.” The figure pointed towards the cache in the woods. If found by regional travelers, they knew to respect the hidden goods and to leave them unharmed.[67] The Frenchman La Tulipe was rather well known to have a certain hiding placed referred to as “Cache la Tulipe.” He, like Native peoples, “deposit[ed] their skins and often suspended to poles or laid over a pole placed upon two forked posts in sight of the river, until their return from hunting; these deposits are considered as sacred and few examples exist of their being plundered.”[68]

Conclusion

Native drawn or created maps that survive today deserve tremendous attention for all that they communicate and preserve within the historical record. First, they reveal a great deal about Native peoples’ spatial understanding of their respective regions. But they also provide significant information on the lifeway of the Native peoples and serve as historical documents that show how information was shared with Europeans and later Americans. Native maps were topologically structured with only the most vital of information communicated. Nonetheless, “they were born of experience and oral tradition,” they showed relationship between points, they communicated understanding of the world that surrounded them.[69]

Review these questions and prepare for discussion in class.

- The Catawba map, mentioned earlier, has a rather intriguing history. While it is, for the most part, out of the realm of the French Mississippi River Valley, it does have a direct relationship with an additional map, the map of the nations between South Carolina and the Mississippi. This latter map, claimed as created by the Chickasaws, and very briefly discussed in this video, was presented to the Governor of South Carolina, Francis Nicholson, sometime after his arrival in the region in 1721. Originally drawn on deerskin by a Native person, it was later copied for preservation and contains important references to Mississippi Nations. Thankfully, the British National Archives in Kew, England maintains a copy of this map today. By examining this map, what do you think it signifies based on what you know from the Catawba map? Is this second map Cherokee drawn, Chickasaw drawn or created by someone else? Perhaps this quotation can help you decipher this map:

“Nicholson, who was then governor of South Carolina, received from an Indian chief a map of the whole of southeastern North America painted on a deer skin. Showing rivers, coastlines, tribal locations, and Indian trails, it appears on first examination to terminate to the west at the Mississippi. However, squeezed between that river and the hind end of the skin are grossly distorted representations of the Red and Arkansas rivers, as well as named sites of Indian villages associated with the rivers. Of these villages, the following can be recognized with reasonable certainty: on the Red, the Natchitoches (Notaukw), Kadohadacho (Katutaucejo), and Kichai (Kejoo); on the Arkansas, the Tawakoni (Tovocolau), Kansa (Causau), Pawnee (Pauncasau), and Comanche (Commaucerlau). Neither of the maps received by Governor Nicholson indicate the existence of the grassland environment far up the Red and Arkansas rivers.”[70]

- Compare European cartography to that of the Native peoples. What are the significant differences between the two?

- Jean Couture was an early resident of Arkansas Post. But by 1688, he seemed to be an explorer of other parts of North American, in particular areas to the west of the Mississippi. By some accounts, he is purported to have drawn this map, and then by the early 1700s, he was in South Carolina. Did he draw this map? Did he draw it through his own personal experiences or did he draw from others’ tales of travel. Click on this link to examine this map housed at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Describe what you see; hypothesize what is possible.

- Here are three maps, each of which have a different designated cartographer. What are your thoughts? Did three different people design these maps? or two? or one? What similarities exist? What differences? Are they strictly European drawn or do you believe that Native peoples had a hand in their creation?

- Ian Chambers, “A Cherokee Origin for the ‘Catawba’ Deerskin Map (c. 1721),” Imago Mundi 65, part 2, (2013): 209. ↵

- John Lawson, A New Voyage to Carolina: Containing the Exact Descriptions and Natural History of That Country (London, 1709), 204. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 79-80; Chretien Le Clercq, New Relation of Gaspesia: With the Customs and Religion of the Gaspesian Indians, ed. and trans. William Francis Ganong (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1910), 136. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 81; Joseph-Francois Lafitau, Customs of the American Indians Compared with the Customs of Primitive Times, vol. 2, trans. and ed. William N. Fenton and Elizabeth L. Moore (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1974-77), 130. ↵

- Louis Armond de Lom d'Arce, Baron de Lahontan, New Voyages to North-America, vol. 2 (London: H. Bonwicke and others, 1703), 13-14. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 53. ↵

- Kevin O'Briant, "Too Né's World: The Arikara Map and Native American Cartography," We Proceeded On, Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation 14, no. 2 (May 2018): 9; Malcolm Lewis, “Indian Maps: Their Place in the History of Plains Cartography,” Great Plains Quarterly 4, no. 2 (Spring 1984): 93-94; Alice C. Fletcher, "Star Cult among the Pawnee: A Preliminary Report," American Anthropologist, n.s. 4 (1902): 730-36; Ralph N. Buckstaff, "Stars and Constellations of a Pawnee Sky Map," American Anthropologist, n.s. 29 (1927): 279-85. ↵

- Martha Ann Rolingson, "Toltec Mounds Site & State Park,Arkansas Archeological Survey (2020) https://archeology.uark.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Toltec-Flyer-Color-2020.pdf ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 67-68; Richard Hakluyt, The Principal Navigations: Voyages Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation, vol. 8 (Glasgow: James MacLehose, 1903-5), 270-71. ↵

- Henri Joutel, A Journal of La Salle’s Last Voyage (New York, 1966), 149. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 52 & 69; Gamaliel Smethurst, A Narrative of an Extraordinary Escape out of the Hands of the Indians, in the Gulph of St. Lawrence (London, 1774), 14. ↵

- Lewis, “Indian Maps,” 54. ↵

- Sabo et al., “Cosmological Landscapes," 261-273. ↵

- Sabo et al., “Cosmological Landscapes,” 261. ↵

- Sabo et al., “Cosmological Landscapes,” 263; P. Radin, Winnebago Hero Cycles: A Study in Aboriginal Literature, Memoir 1 (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Studies in Anthropology and Linguistics, 1948); J. A. Brown, "On the identity of the Birdman within Mississippian Period art and iconography," in Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms: Interpretations of Mississippian Iconography, eds. F.K. Reilly III & J.F. Garber (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007), 56–106. ↵

- Sabo et al., “Cosmological Landscapes,” 264. ↵

- Sabo et al., “Cosmological Landscapes,” 261. ↵

- Sabo et al., “Cosmological Landscapes,” 264. ↵

- Jan F. Simek, Alan Cressler, Nicholas P. Herrmann, & Sarah C. Sherwood, "Sacred Landscapes of the South-eastern USA: Prehistoric Rock and Cave Art in Tennessee," Antiquity 87 (2013): 442. ↵

- Simek et al., "Sacred Landscapes," 443. ↵

- George Sabo, III, "The Terán Map and Caddo Cosmology," in Timothy K. Perttula and Chester P. Walker, eds., The Archaeology of the Caddo (University of Nebraska Press: 2012), 431. ↵

- Sabo,"Terán Map," 439. ↵

- Sabo, "Terán Map," 440. ↵

- Sabo, "Terán Map," 441. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 84. ↵

- Jean Delanglez, trans. and ed., The Journal of Jean Cavelier: The Account of a Survivor of La Salle's Texas Expedition, 1684-1688 (Chicago: Institute of Jesuit History, 1938), 103. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 105. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 176. ↵

- Thwaites, "Relation of 1652-53," JRAD, vol. 40 (Cleveland, Ohio: Burrows Brothers, 1898), 203-5. ↵

- Recorded in William Johnson, The Papers of Sir William Johnson, vol. 2 (Albany: University of the State of New York, 1921-65), 861. ↵

- Gray & Fiering, Language Encounter, 131. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 176. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 52; Northern Cheyenne Language and Culture Center Title VII ESEA Bilingual Education Program, English-Cheyenne Student Dictionary (Lame Deer, Mont., 1976), 61, 66 & 78. ↵

- Keith H. Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache (1996, Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press), 41-43. ↵

- "This map, made by an Indian named Miguel, perhaps from within what is now southern Texas, has proved difficult to interpret, but it certainly includes San Gabriel in the Rio Grande Valley, New Mexico, and possibly Mexico City; it almost certainly represents rivers, trails, and settlements on the Texas coastal plain and southern Great Plains. The map is endorsed "Pintura que por mando de Don Franco Valverde ...," 1602. MS, 31 x43 cm., Estante 1, Cajon 1, Legajo 3/22, Ramo 4, Archivo General de Indias, Seville."; Lewis, “Indian Maps,” 101, FN26. ↵

- Arnold, “Arkansas Illustrated,” 119. ↵

- Morris S. Arnold, Colonial Arkansas 1686-1804: A Social and Cultural History (Fayetteville, Ark: University of Arkansas Press, 1991), 31, 99-101; ↵

- Arnold, “Arkansas Illustrated,” 123. ↵

- Arnold, “Arkansas Illustrated,” 129-130. ↵

- Arnold, “Arkansas Illustrated,” 136. ↵

- It is possible that Henri de Tonti drew this map for the missionaries himself. There simply is no exact record of its origin. ↵

- Chambers, “Cherokee Origin,” 211; “Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and West Indies, March, 1720 to December 1721." Preserved in the Public Record Office (London, HMSO, 1933), entry 217.; William J. Rivers, A Chapter in the Early History of South Carolina (Charleston, SC, Walter, Evans & Cogswell, 1874), 79. ↵

- Chambers, “Cherokee Origin,” 212. ↵

- Gregory A. Waselkov, “Indian Maps of the Colonial Southeast,” in Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southwest, ed. Peter H. Wood, Gregory A. Waselkov, and M. Thomas Hatley (Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1989); Mark Warhus, Another America: Native American Maps and the History of our Land (New York, St, Martins Press, 1997). ↵

- Chambers, “Cherokee Origin," 212. ↵

- Chambers, “Cherokee Origin,” 209-11. ↵

- Chambers, “Cherokee Origin,” 212-13; Henry Read McIlwaine, ed., Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia, vol. IV, October 25, 1721-October 28, 1739 (Richmond, Virginia State Library, 1930), 1-2. ↵

- Chambers, “Cherokee Origin,” 213; Rena Vassar, ed., “Some short remarks on the Indian trade in the Charikees and in management thereof since the Year 1717,” Ethnohistory 8, no. 4 (1961): 412, 415-416. ↵

- Chambers, “Cherokee Origin,” 213. ↵

- Chambers, “Cherokee Origin,” 214; James Mooney, History, Myths and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee (Bright Mountain Books, 1992), 242-49. ↵

- [A Chickasaw Indian], "Nations Amies et Ennemies des Tchikachas . . . Ie Sept Septembre 1737," transcribed by Alexander de Batz, MS, General Correspondence of Louisiana C.13, V.22, Archives des Colonies, Paris. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps, 101-02; James R. Atkinson, "The Ackia and Ogoula Tchetoka Chickasaw Village Locations in 1736 during the French-Chickasaw War," Mississippi Archaeology 20 (1985): 53-72; See Waselkov, "Indian Maps," 332-34 (note 145); Marc de Villiers du Terrage, "Note sur deux cartes dessinées par les Chikachas en 1737," Journal de la Societe des Americanistes de Paris, n.s. 13 (1921): 7-9; Patricia Galloway, "Debriefing Explorers: Amerindian Information in the Delisles' Mapping of the Southeast," in Cartographic Encounters: Perspectives on Native American Mapmaking and Map Use, ed. G. Malcolm Lewis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998): Chapter 10. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 103-04; 171. See Waselkov, "Indian Maps," 329-34; Villiers du Terrage, "Note sur deux cartes." ↵

- https://guides.loc.gov/native-american-spaces/cartographic-resources/indian-maps-mapping ↵

- https://www.wdl.org/en/item/9587/ ↵

- Samuel de Champlain, The Works of Samuel de Champlain, ed. H. P. Biggar, II, (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1922), 140-41. ↵

- O'Briant, "Too Né's World," 8. ↵

- Thwaites, "Marquette's First Voyage," JRAD, vol. 59, 91-93. ↵

- Lewis, “Indian Maps,” 102; Lawrence van den Bosh, Untitled pen- and-ink manuscript map of the lower Mississippi valley that was accompanied by a letter dated North Sassifrix, 19 October 1694. MS 339, Map 1, 32 x 38 cm., no. 59, Edward E. Ayer Collection, Newberry Library, Chicago. ↵

- “Notes de Claude Delisle sur la Géographie sur la Louisiane, vers 1704, ANF, AM, Série 2JJ, Vol. 56, no. X, 17. ↵

- Basso, Wisdom, 14. ↵

- Basso, Wisdom, 12. ↵

- Ruth Irene Jones, “Hot Springs: Ante-Bellum Watering Place,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 14, no. 1, (1955): 3. ↵

- Cécile Vidal, Caribbean New Orleans, Empire, Race, and the Making of a Slave Society (UNC Press, 2019), 98. ↵

- David Wheat, “My Friend Nicolas Mongoula Africans, Indians, and Cultural Exchange in Eighteenth-Century Mobile,” in Richmond F. Brown, ed., Coastal Encounters, The Transformation of the Gulf South in the Eighteenth Century (University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 117. ↵

- Nuttall, Journal of Travels, 92. ↵

- Joseph Patrick Key, “Indians and Ecological Conflict in Territorial Arkansas,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59, no. 2 (2000): 132-133; Others that talk about this include: William Dunbar, “Journal of a Voyage,” in Eron Rowland, ed., Life, Letters, and Papers of William Dunbar (Jackson: Press of the Mississippi Historical Society, 1930), 245; George Hunter, “Journal of an Excursion from Natchez on the Mississippi up the River Ouachita 1804-1805,” in John Francis McDermott, ed., The Western Journals of Dr. George Hunger 1796-1805, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series v. 53, part 4 (July 1963), 95; George W. Featherstonhaugh, Excursion through the Slave States (London: John Murray, 1844), 2:123. ↵

- McDermott, Journals of Dr. George Hunter, 93, fn. 50. ↵

- Lewis, “Maps,” 52. ↵

- Lewis, “Indian Maps,” 102; Cacique (Chickasaw?), "A Map Describing the Situation of the several Nations of Indians between South Carolina and the Mississippi; was Copyed from a Draught Drawn upon a Deer Skin by an Indian Cacique and Presented to Francis Nicholson Esqr. Governor of Carolina." MS (ca. 1720), 114 x 142 cm., CO 700, North American Colonies General, No.6 (2), Public Record Office, London. ↵