7 Connectivism and Connective Knowledge: Essays on Meaning and Learning Networks

Stephen Downes

Connectivism and Connective Knowledge: Essays on meaning and learning networks

Stephen Downes

National Research Council Canada

ISBN: 978-1-105-77846-9

Version 1.0 – May 19, 2012 Stephen Downes

Copyright (c) 2012

This work is published under a Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA

This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit the author and license your new creations under the identical terms.

View License Deed: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0

Contents

Networks, Connectivism and Learning 53

Semantic Networks and Social Networks 55

The Space Between the Notes 62

The Vagueness of George Siemens 63

What Networks Have In Common 68

The Personal Network Effect 73

Connectivism and its Critics: What Connectivism Is Not 92

Connectivism and Transculturality 95

A Truly Distributed Creative System 118

What’s The Number for Tech Support? 124

Informal Learning: All or Nothing 128

Meaning, Language and Metadata 139

Principles of Distributed Representation 141

On Thinking Without Language 169

Naming Does Not Necessitate Existence 175

Connectivism, Peirce, and All That 191

Brakeless Trains – My Take 193

Networks, Connectivism and Learning

Semantic Networks and Social Networks

This article published as Semantic Networks and Social Networks in The Learning Organization Journal Volume 12, Number 5 411-417 May 1, 2005.43

Abstract

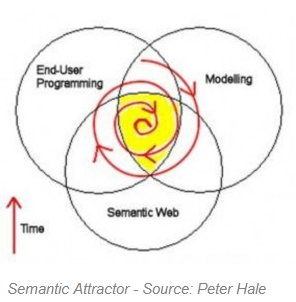

Purpose: To illustrate the need for social network metadata within semantic metadata.

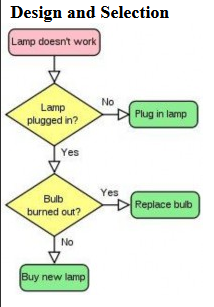

Design/methodology/approach: Surveys properties of social networks and the semantic web, suggests that social network analysis applies to semantic content, argues that semantic content is more searchable if social network metadata is merged with semantic web metadata.

Findings: The use of social network metadata will alter semantical searches from being random with respect to source to direct with respect to source, which will increase the accuracy of search results.

Research limitations/implications: Suggests that existing XML schemas for semantic web content be modified.

Practical implications: Introduction and overview of a new issue.

Originality/value: Foundational to the concept of the semantic social network; will be useful as an introduction to future work.

Keywords: Information networks, Internet, Social networks Paper type: Conceptual paper

Semantic Networks and Social Networks

A social network is a collection of individuals linked together by a set of relations. In discussions of social networks the individuals in question are usually humans, though work in social network theory has found similarities between communities of humans and, say, communities of crickets44 or members of a food web.45 Entities in a network are called “nodes” and the connections between them are called “ties”.46 Ties between nodes may be represented as matrices, and the properties of these networks therefore studied as a subset of graph theory.47

A key property of social networks is that nodes that might be thought of as widely distant from each other – a farmer in India, say, and the President of the United States – may actually be much more closely connected that otherwise imagined. This phenomenon, sometimes known as “six degrees”, was measured48 and, as the name suggests, no more than six steps were required to connect any two people in the United States.49 With the arrival of the internet as a global communications network ties between individuals became both much easier to create and much easier to measure.

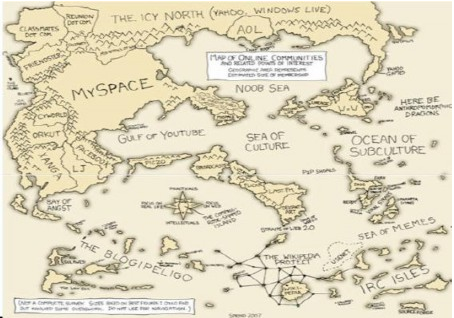

Social networking web sites fostering the development of explicit ties between individuals as “friends” began to appear in 2002. Sites such as Friendster, Tribe, Flickr the Facebook and LinkedIn were early examples. Less explicitly based on fostering relationships than, say, online dating sites, these sites nonetheless sought to develop networks or “social circles” of individuals of mutual interest. LinkedIn, for example, seeks to connect potential business partners or prospective employers with potential employers. Flickr connects people according to their mutual interest in photography. And numerous sites offer dating or matchmaking services. After an initial surge of interest, however, social networking sites have tended to stagnate50 It is arguable that social networking, by itself, has limited practical use.

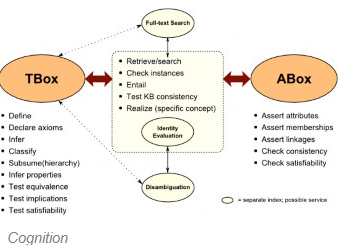

The semantic web, as originally conceived by Tim Berners-Lee, “provides a common framework that allows data to be shared and reused across application, enterprise, and community boundaries”51 Developed using the resource description framework, it consists of an interlocking set of statements (known as “triples”). “Information is given well-defined meaning, better enabling computers and people to work in cooperation.”52 The semantic web is therefore, a network of statements about resources.

In particular, RDF enables the creation of statements intended to describe different types of resources. The terms used in these statements are defined in schemas, themselves RDF documents, which list the terms to be used and (in some cases) the types of values allowed, and the relations between them. “Using RDF Schema, we can say that ‘Fido’ is a type of ‘Dog’, and that ‘Dog’ is a sub class of animal.” Beyond schemas, ontologies enable complex representations of related entities and their descriptions.

Though applications of the semantic web in particular have thus far been limited, there have emerged since its introduction numerous projects characterizing and encoding descriptions of different types of resources in XML.53 The majority of these projects seem to be centred around the classification of information and resources. For example, learning object metadata (LOM) describes learning resources. Dublin Core provides bibliographic information about resources. These resources are typically identified explicitly in the XML or RDF, typically using a uniform resource identifier (URI) based on its address on the world wide web, or via some other form of identifier system, such as digital object identifier (DOI).

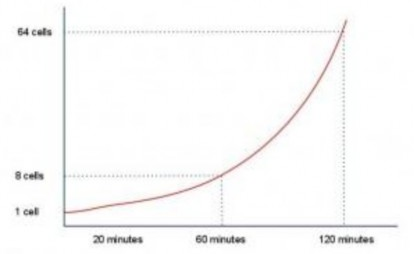

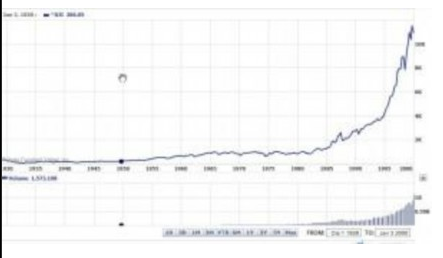

Outside professional and academic circles, arguably the most widespread adoption of the semantic web has been in the use of RSS. RSS, known variously as rich site summary, RDF site summary or really simple syndication, was devised by Netscape in order to allow content publishers to syndicate their content, in the form of headlines and short introductory descriptions, on its My Netscape web site.54 The use of RSS has increased exponentially, and now RSS descriptions (or its closely related cousin, Atom) are used to summarize the contents of 100s of newspapers and journals, weblogs (including the roughly eight million weblogs hosted collectively by Blogger, Typepad, LiveJournal and Userland), wikis and more.

There are no doubt purists who deny that RSS is an instantiation of the semantic web. However, all RSS files are undeniably written in XML, and a type of RSS (specifically, RSS 1.0) is explicitly written in RDF.55 At its core, RSS consists of some simple XML elements: a “channel” element defining the publication title, description and link; and a series of “item” elements defining individual resource titles, descriptions and links. Since, RSS 1.0, however, the RSS format has allowed these basic elements to be extended; the role of schemas is fulfilled by namespaces, and these namespaces define (sometimes implicitly) a non-core vocabulary. Such extensions (also known in RSS 1.0 as “modules”) include Dublin Core, Creative Commons, Syndication and Taxonomy.56

Initiatives to represent information about people in RDF or XML have been fewer and demonstrably much less widely used. The HR-XML (Human Resources XML) Consortium has developed a library of schemas “define the data elements for particular HR transactions, as well as options and constraints governing the use of those elements”.57 Customer Information Quality TC, an OASIS specification, remains in formative stages.58 And the IMS learner information package specification restricts itself to educational use.59 It is probably safe to say that there is no commonly accepted and widely used specification for the description of people and personal information. As suggested above, developments in the semantic web have addressed themselves almost entirely to the description of resources, and in particular, documents.

Outside the professional and academic circles, there have been efforts to represent the relations between persons found in social networks explicitly in XML and RDF. Probably the best known of these is the Friend of a Friend (FOAF) specification.60 Explicitly RDF, a FOAF description will include data elements for personal information, such as one’s name, e-mail address, web site, and even one’s nearest airport. FOAF also allows a person to list in the same document a set of “friends” to whom the individual feels connected. A similar initiative is the XHTML Friends Network (XFN) (GPMG, 2003). XFM involves the use of “rel” attributes within links contained in a blogroll (a “blogroll” is a list of web sites the owner of a blog will post to indicate readership).

Though FOAF and XFN have obtained some currency, it is arguable that they have declined to the same sort of stagnation that has befallen social network web sites. While many people have created FOAF files, for example, few applications (and arguably no useful applications) have been developed for FOAF. And while some useful extensions to FOAF have been proposed (such as a trust metric, PGP public key, and default licensing scheme), these have not been adopted by the community at all.

Perhaps, given the demonstrable lack of enduring interest in social network systems, either site- based, as in LinkedIn? and Orkut, or semantic web-based, as in FOAF or XFN, it could be argued that there is no genuine need for a social network system (beyond, perhaps, matching and dating sites). Perhaps, as some have argued, such systems, once they get too large to be manageable, simply collapse in on themselves, their users suffocated under the weight of millions of enquiries and advertising messages, as happened to e-mail, Usenet and IRC.61

But the evidence seems to weigh against this supposition. Certainly, the management of personal information has long been touted as necessary for authentication. Authentication – i.e. a mechanism of proving that a person is who they say they are – is used to control access to restricted information. Projects such as Microsoft s Passport and the liberty alliance have for years attempted to promote a common authentication scheme. Sites such as LiveJournal and Blogger have begun to require login access in order to submit comments, as a means of discouraging spam. Newspapers, online journals and online communities typically require some sort of login process. Projects such as SxIP and light-weight identity (LID)62 have attempted to create a single sign-on solution for logins. So there is a need for personal descriptions, at least to control access.

We could perhaps leave descriptions of identity as something for individual sites to work out were there not wider issues pertaining to the semantic web that also require at least some element of personal identity to address. To put the problem briefly: so long as descriptions of resources are based solely on the content of those resources then users of the semantic web will be hampered in their efforts to learn about new resources outside the domain of their own expertise. The reason for this is what might be called the “dictionary principle” – in order to find a resource, the searcher must already know about the topic domain they are searching through, since resources are defined in terms specific to that domain (in other words if you want to find a word in a dictionary, you have to already know how to spell it).

In fact, what has tended to happen in the largest current implementation of the semantic web, the network of RSS resources, is that searchers have, within certain parameters, tended to seek out resources randomly. They type in a search term in Google, for example, without any foreknowledge of where the resource they are seeking will turn up. They tend to link to sources they find in this manner; thus, the network of connections between resources (expressed in RSS, as on web sites, as links) manifests itself as a random network.

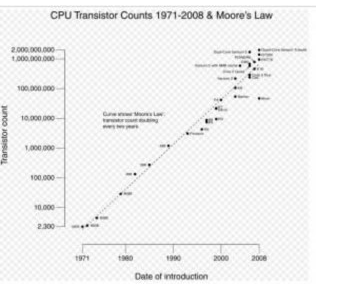

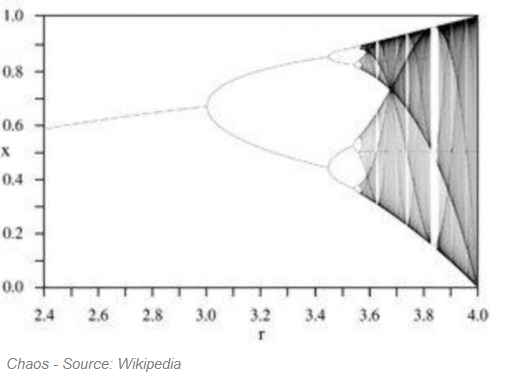

The proof of this is found in the studies of social networks discussed at the beginning of this paper. The links found in web pages are instances of what are known as “weak ties”. Weak ties are are acquaintances who are not part of your closest social circle, and as such have the power to act as a bridge between your social cluster and someone else’s.63 Weak ties created at random in this way lead to what Gladwell called “supernodes” individuals with many more ties than other resources. (Gladwell, in other words, some sites get most of the links, while most others get many fewer links. “A power-law distribution basically indicates that 80 per cent of the traffic is going to 1 per cent of the participants in the network.”64

Numerous commentators, from Barabasi forward, have made the observation that power laws occur naturally in random networks, and some pundits, such as Clay Shirky, have shown that the distribution of visitors to web sites and links to web sites follow a power law distribution.65 Our purpose here is to take the inference in the opposite direction: because readership and linkage to online resources exhibits a power law distribution, it follows that these resources are being accessed randomly. Therefore, despite the existence of a semantic description of these resources, readers are unable to locate them except via the location of an individual – a super connector – likely to point to such resources.

It is reasonable to assume that a less random search would result in more reliable results. For example, as matters currently stand, were I to conduct a search for “social networking” then probability dictates that I would most likely land on Clay Shirkey, since Shirky is a super- connector and therefore cited in most places I am likely to find through a random search. But Shirky s politician affiliation and economic outlook may be very different from mine; it would be preferable to find a resource authored by someone who shares my own perspective more closely. Therefore, it is reasonable to suppose that if I were to search for a resource based on both the properties of the resource and the properties of the author, I would be more likely to find a resource than were I to search for a random author.

Such a search, however, is impossible unless the properties of the author are available in some form (presumably, something like an RDF file), and also importantly, that the properties of the author are connected in an unambiguous way to the resources being sought.

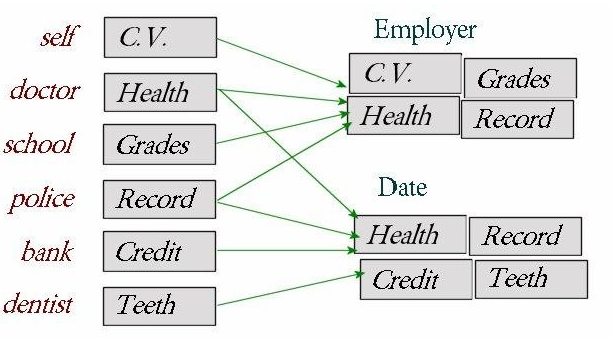

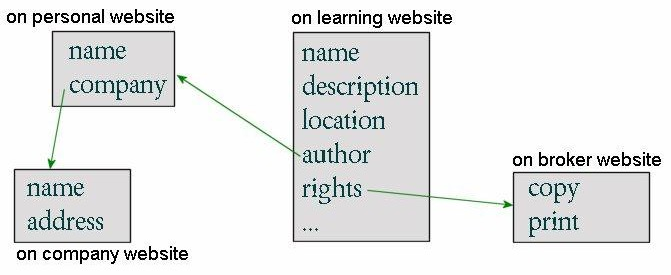

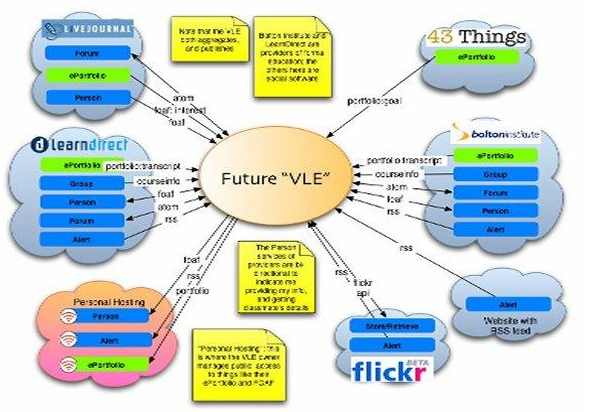

I have proposed66 that social networking be combined explicitly with the semantic web in what I have called the semantic social network (SSN). Essentially, SSN involves two major components: first, that there be, expressed in XML or RDF, descriptions of persons (authors, readers, critics) publicly available on the web, sometimes with explicit ties to other persons; and second, that references to these descriptions be employed in RDF or XML files describing resources.

Neither would at first glance seem controversial, but as I mention above, there is little in the way of personal description in the semantic web, and even more surprisingly, the vast majority of XML and RDF specifications identify persons (authors, editors, and the like) with a string rather than with a reference to a resource. And such strings are ambiguous; such strings do not uniquely identify a person (after all, how many people named John Smith are there?) and they do not identify a location where more information may be found (with the result that many specifications require that additional information be contained in the resource description, resulting in, for example, the embedding of VCard information in LOM files).

It should be immediately obvious that the explicit conjunction of personal information and resource information within the context of a single distributed search system will facilitate much more fine-grained searches than either system considered separately. For example, were I look for a resource on social networks , I may request resources about social networks authored by people who are similar to me , where similarity is defined as a mapping of commonalities of personal feature sets: language and nationality, say, commonly identified friends , or even similarities in licensing preferences. Or, were I to (randomly or otherwise) locate an individual with, to me, an interesting point of view, I could “search for all articles written by n and friends of n”.

Identity plays a key role in projected future developments of the semantic web. In his famous architecture diagram , Tim Berners-Lee identifies a digital signature as being the backbone of RDF, ontology, logic and proof.67 A digital signature establishes what he calls the provenance of a statement: we are able to determine not only that “A is a B”, but also according to whom A is a B. “Digital signatures can be used to establish the provenance not only of data but also of ontologies and of deductions.”68 But as useful as a digital signature may be for authentication, a digital signature is an unfaceted identification. To know something about the person making the assertion, it will be necessary to attach a personal identity to an XML or RDF description.

As we examine the role that personal identity plays in semantic description, it becomes apparent that much more fine-grained descriptions of resources themselves become possible. For there are three major ways in which a person may be related to a resource: as the author or creator of the resource; as the user or consumer of the resource; and as a commentator or evaluator of the resource. Each of these three types of person may create metadata about a resource. An author may give a resource a title, for example. A user may give the resource a “hit” or a reference (or a “link”). And a commentator may provide an assessment, such as “good” or “board certified”. Metadata created by these three types of persons may be called “first party metadata”, “second party metadata” and “third party metadata”, respectively.

The semantic web and social networking have each developed separately. But the discussion in this short paper should be sufficient to have shown that they need each other. In order for social networks to be relevant, they need to be about something. And in order for the semantic web to be relevant, it needs to be what somebody is talking about. Authors need content, and content needs authors.

Footnotes

43 Stephen Downes. Semantic Networks and Social Networks. The Learning Organization Journal Volume 12, Number 5 411-417 May 1, 2005. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/mcb/119/2005/00000012/00000005/art00002

44 M. Buchanan. Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Science of Networks. 2002. Perseus Publishing, Cambridge, MA. p. 49.

45 Ibid. p. 17.

46 J.M. Cook. Social Networks: A Primer. Ebook. 2001. Available at: http://www.soc.duke.edu/jcook/networks. html

47 Garton, L., Haythornthwaite, C. and Wellman, B. “Studying online social networks”, JCMC, Vol. 3 No. 1. 1997. http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol3/issue1/garton.html

48 Stanley Milgram. “The Small World Problem”, Psychology Today, pp. 60-7, May 1967. http://smallworld.sociology.columbia.edu/ (link not currently functioning).

49 Buchanan, M. Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Science of Networks, Perseus Publishing, Cambridge, MA. 2002.

50 J. Aquino. The Blog is the social network. Weblog Post. 2005. http://jonaquino. blogspot.com/2005/04/blog-is-social-network.html

51 World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). Semantic Web. Paper presented at the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). 2001. http://www.w3.org/2001/sw/

52 Tim Berners-Lee, Hendler, J. and Lassila, O. The Semantic Web. Scientific American, May, 2001. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?articleID=00048144-10D2-1C70-84A9809EC588EF21&catID=2

53 Stephen Downes. Canadian Metadata Forum – Summary. Stephen’s Web (weblog). September 20, 2003. http://www.downes.ca/post/52

54 Stephen Downes. Content Syndication and Online Learning. Stephen’s Web (weblog). September 22, 2000. http://www.downes.ca/post/148

55 G. Beged-Dov, et al. RDF Site Summary 1.0. 2001. http://web.resource.org/rss/1.0/ spec

56 G. Beged-Dov, et al. RDF Site Summary 1.0 Modules. 2001. http://web.resource. org/rss/1.0/modules/

57 HR-XML Consortium. “Downloads”. 2005. p. 139.

58 OASIS. Customer Information Quality TC. 2005. http:// www.oasis-open.org/ committees/ciq/charter.php

59 IMS Global Learning Consortium. IMS Learner Information Package Specification. 2005 http://www.imsglobal.org/profiles/

60 Edd Dumbill. Finding Friends with XML and RDF. XML Watch (weblog). 2002. Accessed June 1, 2002. http://www-106.ibm. com/developerworks/xml/library/x-foaf.html

61 A.L. Cervini, A.L. Network connections: an analysis of social software that turns online introductions into offline interactions. Master’s thesis, Interactive Telecommunications Program, NYU. 2003. http://stage.itp.tsoa.nyu.edu/alc287/thesis/thesis.html

62 Light-weight Identity Description. Website. No longer extant. Original URL: 2005. http://lid.netmesh. org/

63 Cervini, 2003.

64 Albert-Laszlo Barabasi (2002), Linked: The New Science of Networks, Perseus Press, Cambridge, MA, p. 70.

65 Clay Shirky. Power Laws, Weblogs, and Inequality. Weblog post. February 8, 2003.http://www.shirky.com/writings/powerlaw_weblog.html

66 Stephen Downes. The Semantic Social Network. Stephen’s Web (weblog). February 14, 2004. http://www.downes.ca/post/46

67 Tim Berners-Lee. Semantic Web XML2000. 2000. http://www.w3.org/2000/Talks/ 1206-xml2k-tbl/slide10-0.html

68 Edd Dumbill. Berners-Lee and the Semantic Web Vision. XML.com (ezine). December, 2000. http://www.xml. com/pub/a/2000/12/xml2000/timbl.html

Further reading

Gladwell, M. (2000), The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, MA, pp. 45-6.

Vitiello, E. (2002), FOAF, available at: www.perceive.net/xml/foaf.rdf

Moncton, October 10, 2005

The Space Between the Notes

On reading Kathy Sierra…69

We turn clay to make a vessel; but it is on the space where there is nothing that the usefulness of the vessel depends. – Tao Te Ching

An old insight, often forgotten.

Listening to the recent talks from TED, all these speakers were roaring along at top speed, delivering a hundred words a minute. In my own talks, I speak more slowly (something I learned to do to facilitate simultaneous translation). Why would a professional speaker move so quickly, I wondered, when greater comprehension comes from more paced delivery?

Then I understood. A person who speaks quickly appears to be intelligent, appears to be worth listening to, appears, therefore, to be worth paying to speak. Every speech given by one of these speakers is an advertisement for the next.

It’s the same with things, with objects. Greater accumulation conveys the greater appearance of worth. But the sheer mass of objects demonstrates that the only purpose of the one object is the obtaining of another.

In this way, the filling of space results in emptiness. When the purpose of obtaining the one is only for obtaining the next, then you can never have anything.

Footnotes

69 Kathy Sierra. Hooverin’ and the space between notes. Creating Passionate Users (weblog). July 18, 2006. http://headrush.typepad.com/creating_passionate_users/2006/07/hooverin_and_th.html

Moncton, July 19, 2006

The Vagueness of George Siemens

Posted to Half an Hour.

I like George Siemens and he says a lot of good things, but he is often quite vague, an imprecision that can be frustrating. In his discussion70 of my work on connective knowledge, for example, he observes, “In this model, concepts are distributed entities, not centrally held or understood…and highly dependent on context. Simply, elements change when in connection with other elements.” What does he mean by ‘elements’? Concepts? Nodes in the network?

Entities? You can’t just throw a word in there; you need some continuity of reference.

Why is this important? Siemens dislikes the relativism that follows from the model. Fair enough; people disagreed with Kant about the noumenon71 too. But he writes, “I see a conflict with the fluid notions of subjectivity and that items are what they are only in line with our perceptions…and what items are when they connect based on defined characteristics (call them basic facts, if you will)” And I ask, what does he mean by ‘in line’ or ‘defined characteristics… basic facts’ – if they are defined, how can they be basic facts?

Then he says, “I still see a role for many types of knowledge to hold value based on our recognition of what is there.” Now I’m tearing my hair. “Hold value?” What can he mean… does he know? Does he mean “‘Snow is white’ is ‘true’ if and only if ‘snow is white’?” Or is he simply kicking a chair and saying “Thus I refute Berkeley.” In which case I can simply recommend On Certainty72 (one of my favourite books in the world) and move along.

He continues, “The networked view of knowledge may be more of an augmentation of previous categorizations, rather than a complete displacement.” Now I’m quite sure that’s not what he means. He is trying to say something like ‘knowledge obtained through network semantics does not replace knowledge obtained by more traditional means, but merely augments it.’ Fine – if he can give us a coherent account of the knowledge obtained through traditional means. But it is on exactly this point that the traditional theory of knowledge falters. We are left without certainty. You can’t “augment” something that doesn’t exist.

Here is his main criticism: “At this point, I think Stephen confuses the original meaning inherent in a knowledge element, and the changed meaning that occurs when we combine different knowledge elements in a network structure.” Well I am certainly confused, but not, I think, as a result of philosophical error. What can Siemens possibly mean by ‘knowledge element’. It’s a catch-all term, that refers to whatever you want it to – a proposition, a concept, a system of categorization, an entity in a network. But these are very different things – statements about a ‘knowledge element’ appear true only because nobody knows what a ‘knowledge element’ is.

He writes, “Knowledge, in many instances, has clear, defined properties and its meaning is not exclusively derived from networks…” What? Huh? If he is referring to, say, propositions, or concepts, or categorizations, this is exactly not true – but the use of the fuzzy ‘knowledge elements’ serves to preclude any efforts to pin him down on this. And have I ever said “meaning is derived from networks”? No – I would never use a fuzzy statement like ‘derived from’ (which seems to suggest, but not entail, some notion of entailment).

He continues, “The meaning of knowledge can be partly a function of the way a network is formed…” Surely he means “the meaning of a item of knowledge,” which in turn must mean… again, what? A proposition, etc.? Then is he saying, “The meaning of a proposition can be partly a function of the way a network is formed…” Well, no, because it’s a short straight route to relativism from there (if the meaning of a proposition changes according to context, and if the truth of a proposition is a function of its meaning, then the truth of a proposition changes according to the way the network was form).

What is Siemens’s theory of meaning? I’m sorry, but I haven’t a clue. He writes, “The fact that the meaning of an entity changes based on how it’s networked does not eliminate its original meaning. The aggregated meaning reflects the meaning held in individual knowledge entities.” An entity – a node in a network? No.

He has to be saying something like this: for any given description of an event, Q, there is a ‘fact of the matter’, P, such that, however the meaning of Q changes as a consequence of its interaction with other descriptions D, it remains the case that Q is at least partially a function of P, and never exclusively of D. But if this is what he is saying, there is any number of ways it can be shown to be false, from the incidence of mirages and visions to neural failures to counterfactual statements to simple wishful thinking.

But of course Siemens doesn’t have to deal with any of this because his position is never articulated any more clearly than ‘Downes says there is no fact of the matter, there is a fact of the matter, thus Downes is wrong’. To which I reply, simply, show me the fact of the matter.

Show me one proposition, one concept, one categorization, one anything, the truth (and meaning) of which is inherent in the item itself and not as a function of the network in which it is embedded.

Siemens says, introducing my work that I explore “many of the concepts I presented in Knowing Knowledge…and that others (notably Dave Snowden and Dave Weinberger) have long advocated – namely that the structured view of knowledge has given way to more diverse ways of organizing, categorizing, and knowing.”

I don’t think this is true. Siemens, Snowden and Weinberger may all be talking about “more diverse ways of knowing” – but I am not talking about their ‘diverse ways of knowing’ but rather – as I have been consistently and for decades – on how networks learn things, know things, and do things.

Footnotes

70 George Siemens. Knowing Knowledge Discussion Forum. Website. http://www.knowingknowledge.com/ Specific citation no longer extant. Original link: http://knowingknowledge.com/2007/04/toward_a_future_knowledge_soci.php

71 Wikipedia. Noumenon. Accessed April 19, 2007. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noumenon

72 Ludwig Wittgenstein. On Certainty. Blackwell. January 16, 1991. http://books.google.ca/books/about/On_Certainty.html?id=ZGHG6WkVF5EC&redir_esc=y

Moncton, April 19, 2007

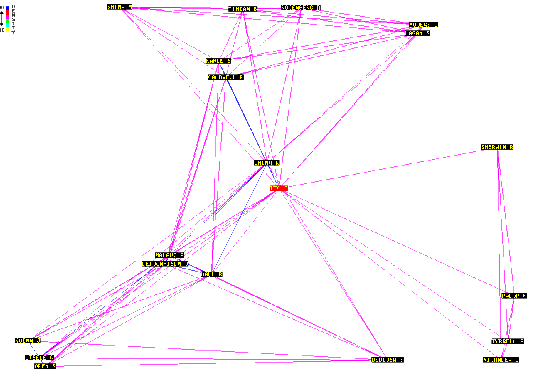

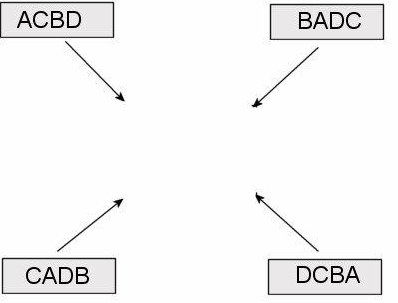

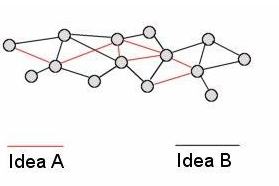

Network Diagrams

Created for Connectivism and Connective Knowledge #cck11

Here is a selection of network diagrams:

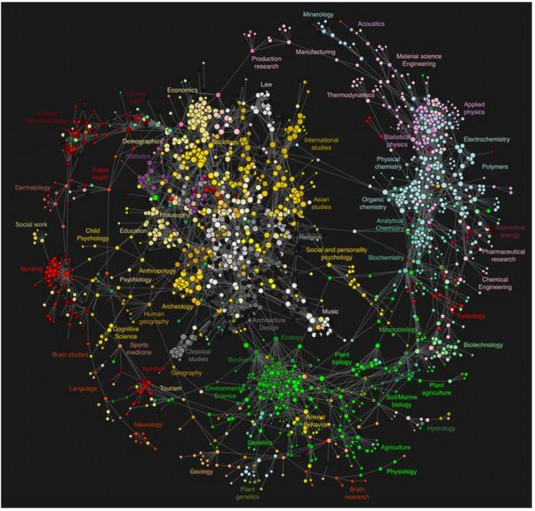

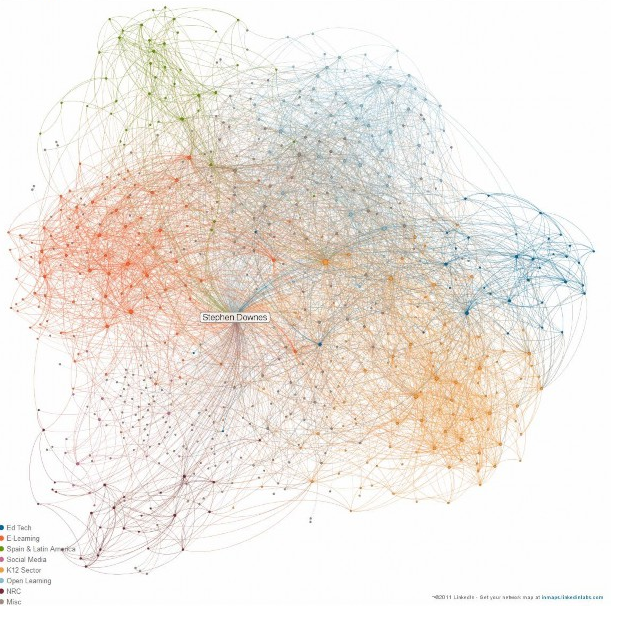

Web of Data. From Linked Data Meetup 73

Last.fm Related Musical Acts. From Sixdegrees.hu74

Map of Science. From Plos One,75 Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science.

Comment

Bonni Stachowiak has left a new comment on your post “Network Diagrams”: LinkedIn just came out with an incredible way of visualizing your professional network connections, called InMaps.76

Downes said… The lnMaps are here: http://inmaps.linkedinlabs.com/

Footnotes

73 Georgi Kobilarov. Meetup Group Photo Album. Web Of Data Meetup. January 21, 2010. http://www.meetup.com/Web-Of- Data/photos/807995/#12724766

74 Sixdegrees.hu. Reconstructing the structure of the world-wide music scene with Last.fm. Undated, accessed January 24, 2011. http://sixdegrees.hu/last.fm/

75 Bollen J, Van de Sompel H, Hagberg A, Bettencourt L, Chute R, et al. (2009) Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science. PLoS ONE 4(3): e4803. http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0004803

76 Bonni Stachowiak. Visualize your network connections #CCK11. Teaching in Higher Education (weblog), January 24, 2011. http://teachinginhighered.com/visualize-your-network-connections-cck11-0

Moncton, November 14, 2010

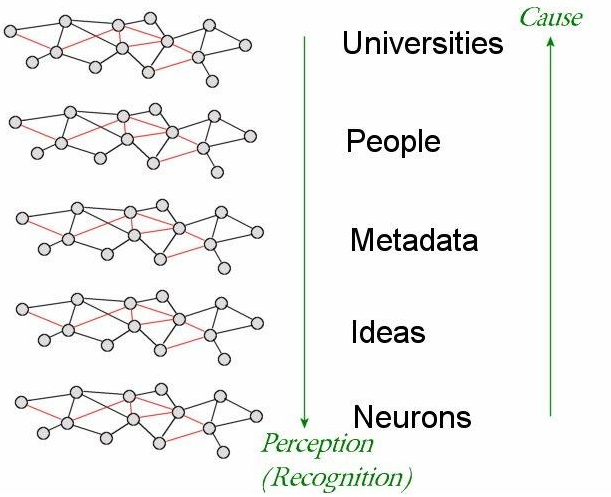

What Networks Have In Common

David T. Jones asks,77 “Does connectivism conflate or equate the knowledge/connections with these two levels (“neuronal” and “networked”)? Regardless of whether the answer is yes or no, what are the implications that arise from that response?”

The answer to the first question is ‘yes’, but with some caveats.

The first caveat is expressed in several of my papers. It is that historically we can describe three major types of knowledge:

- qualitative – i.e., knowledge of properties, relations, and other typically sensible features of entities

- quantitative – i.e., knowledge of number, area, mass, and other features derived by means of discernment or division of entities within sensory perception

- connective – i.e., knowledge of patterns, systems, ecologies, and other features that arise from the recognition of interactions of these entities with each other.

(There is an increasing effect of context-sensitivity across these three types of knowledge. Sensory information is in the first instance context-independent, as (if you will) raw sense data, but as we begin to discern and name properties, context-sensitivity increases. As we begin to discern entities in order to count them, context-sensitivity increases further. Connective knowledge is the most context-sensitive of all, as it arises only after the perceiver has learned to detect patterns in the input data.)

The second caveat is that there is not one single domain, ‘knowledge’, and, correspondingly, not one single entity, the (typically undesignated) knower. Any entity or set of entities that can (a) receive raw sensory input, and (b) discern properties, quantities and connections within that input, can be a knower, and consequently, know.

(Note that I do not say ‘possess knowledge’. To ‘know’ is to be in the state of perceiving, discerning and recognizing. It is the state itself that is knowledge; while there are numerous theories of ‘knowledge of’ or ‘knowledge that’, etc., these are meta-theories, intended to assess or verify the meaning, veracity, relevance, or some other relational property of knowledge with respect to some domain external to that knowledge.)

Given these caveats, I can identify two major types of knowledge, specifically, two major entities that instantiate the states I have described above as ‘knowledge’. (There are many more than two, but these two are particularly relevant for the present discussion).

- The individual person, which senses, discerns and recognizes using the human brain.

- The human society, which senses, discerns and recognizes using its constituent humans.

These are two separate (though obviously related) systems, and correspondingly, we have two distinct types of knowledge, what might be called ‘personal knowledge’ and ‘public knowledge’ (I sometimes also use the term ‘social knowledge’ to mean the same thing as ‘public knowledge’).

Now, to return to the original question, “Does connectivism conflate or equate the knowledge/connections with these two levels (‘neuronal’ and ‘networked’)?”, I take it to mean, “Does connectionism conflate or equate personal knowledge and public knowledge.”

Are they the same thing? No.

Are they each instances of an underlying mechanism or process that can be called (for lack of a better term) ‘networked knowledge’? Yes.

Is ‘networked knowledge’ the same as ‘public knowledge’? No. Nor is it the same as ‘personal knowledge’. By ‘networked knowledge’ I mean the properties and processes that underlie both personal knowledge and public knowledge.

Now to be specific: the state we call ‘knowledge’ is produced in (complex) entities as a consequence of the connections between and interactions among the parts of that entity.

This definition is significant because it makes it clear that:

- ‘knowledge’ is not equivalent to, or derived from, the properties of those parts.

- ‘knowledge’ is not equivalent to, or derived from, the numerical properties of those parts

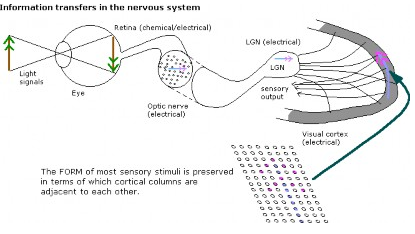

Knowledge is not compositional, in other words. This becomes most clear when we talk about personal knowledge. In a human, the parts are neurons, and the states or properties of those neurons are electro-chemical potentials, and the interactions between those neurons are electro-chemical signals. Yet a description of what a person ‘knows’ is not a tallying of descriptions of electro-chemical potentials and signals.

Similarly, what makes a table ‘a table’ is not derivable merely by listing the atoms that compose the table, and there is no property, ‘tableness’, inherent in each of those atoms. What makes a table a ‘table’ is the organization and interactions (which produce ‘solidity’) between those atoms. But additionally, ascription of this property, being a ‘table’, is context-dependent; it depends on the viewer being able to recognize that such-and-such an organization constitutes a table.

A lot follows from this, but I would like to focus here on what personal knowledge and public knowledge has in common. And, given that these two types of knowledge result from the connections between the parts of these entities, the question now arises, what are the mechanisms by which these connections form or arise?

There are two ways to answer this:

-

- the connections arise as a result of the actual physical properties of the parts, and are unique to each type of entity. Hence (for example) the connections between carbon atoms that arise to produce various organizations of carbon, such as ‘graphite’ or ‘diamond’, are unique to carbon, and do not arise elsewhere

- the connections arise as a result of (or in a way that can be described as (depending on whether you’re a realist about connections)) a set of connection-forming mechanisms that are common to all types of knowledge.

Natural science is the domain of the former. Connective science (what we now call fields such as ‘economics’, ‘education’, ‘sociology’) is the domain of the latter.

One proposition of connectivism (call it ‘strong connectivism’) is that what we call ‘knowledge’ is what connections are created solely as a result of the common connection-forming mechanisms, and not as a result of the particular physical constitution of the system involved. Weak connectivism, by contrast, will allow that the physical properties of the entities create connections, and hence knowledge, unique to those entities. Most people (including me) would, I suspect, support both strong and weak connectivism.

The question “Does connectivism conflate or equate the knowledge/connections with these two levels” thus now resolves to the question of whether strong connectivism is (a) possible, and (b) part of the theory known as connectivism. I am unequivocal in answering ‘yes’ to both parts of the question, with the following caveat: the connection-forming mechanisms are, and are describable as, physical processes. I am not postulating some extra-worldly notion of ‘the connection’ in order to explain this commonality.

These connection-forming mechanisms are well known and well understood and are sometimes rolled up under the heading of ‘learning mechanisms’. I have at various points in my writing described four major types of learning mechanisms:

-

- Hebbian associationism – what wires together, fires together

- Contiguity – proximate entities will link together are form competitive pools

- Back Propagation – feedback; sending signals back through a network

- Settling – eg., conservation of energy or natural equilibrium.

There may be more. For example, Hebbian associationism may consist not only of ‘birds of a feather link together’ but also associationism of compatible types, as in ‘opposites attract’.

What underlying mechanisms exist, what are the physical processes that realize these mechanisms, and what laws or principles describe these mechanisms, is an empirical question. And thus, it is also an empirical question as to whether there is a common underlying set of connection-forming mechanisms.

But from what I can discern to date, the answer to this question is ‘yes’, which is why I am a strong connectivist. But note that it does place the onus on me to actually describe the physical processes that are instances of one of these four mechanisms (or at least, since I am limited to a single lifetime, to describe the conditions for the possibility of such a description).

There is a separate and associated version of the question, “Does connectivism conflate or equate the knowledge/connections with these two levels,” and that is whether the principles of the assessment of knowledge are the same at both levels (and all levels generally).

There are various ways to formulate that question. For example, “Is the reliability of knowledge- forming processes derived from the physical constitution of the entity, or is it an instance of an underlying general principle of reliability.” And, just as above, we can discern a weak theory, which would ground reliability in the physical constitution, and a strong theory, which grounds it in underlying mechanisms (I am aware of the various forms of ‘reliablism’ proposed by Goldman, Swain and Plantinga, and am not referring to their theory with this incidental use of the word ‘reliable’).

As before, I am a proponent of both, which means there are some forms of underlying principles that I think inform the assessment of connection-forming mechanisms within collections of interacting entities. Some structures are more (for lack of a better word) ‘reliable’ than others.

I class these generally as types of methodological principles (the exact designation is unimportant; Wittgenstein might call them ‘rules’ in a ‘game’). By analogy, I appear to the mechanisms we use to evaluate theories: simplicity, parsimony, testability, etc. These mechanisms do not guarantee the truth of theories (whatever that means) but have come to be accepted as generally (for lack of a better word) reliable means to select theories.

In the case of networks, the mechanisms are grounded in a distinction I made above, that knowledge is not compositional. Mechanisms that can be seen as methods to define knowledge as compositional are detrimental to knowledge formation, while mechanisms that define knowledge as connective, are helpful to knowledge formation.

I have attempted to characterize this distinction more generally under the heading of ‘groups’ and ‘networks’. In this line of argument, groups are defined compositionally – sameness of purpose, sameness of type of entity, etc., while networks are defined in terms of the interactions. This distinction between groups and networks has led me to identify four major methodological principles”

-

-

- autonomy – each entity in a network governs itself

- diversity – entities in a network can have distinct, unique states

- openness – membership in the network is fluid; the network receives external input

- interactivity – ‘knowledge’ in the network is derived through a process of interactivity, rather than through a process of propagating the properties of one entity to other entities

-

Again, as with the four learning mechanisms, it is an empirical question as to *whether* these processes create reliable network-forming networks (I believe they do, based on my own observations, but a more rigorous proof is desirable), and I am by this theory committed to a description of the *mechanisms* by which these principles engender the reliability of networks.

In the case of the latter, the mechanism I describe is the prevention of ‘network death’. Network death occurs when all entities are of the same state, and hence all interaction between them has either stopped or entered into a static or stead state. Network death is the typical result of what are called ‘cascade phenomena’, whereby a process of spreading activation eliminates diversity in the network. The four principles are mechanisms that govern, or regulate, spreading activation.

So, the short answer to the first question is “yes”, but with the requirement that there be a clear description of exactly what it is that underlies public and personal knowledge, and with the requirement that it be clearly described and empirically observed.

I will leave the answer to the second question as an exercise for another day.

Downes said…

-

What are strong and weak connectivism?

Let me give you an example.

Salt is created by the forming of a link between an atom of sodium and an atom of chlorine. While bonds of this sort are common, they require that the two elements be of a specific type. If the elements are different, the resulting compound will not be salt, but something quite different.

This is weak connectivism. The nature of the connection, and indeed, whether the connection will form at all, depends on the nature of the entities.

Here’s another example. Birds (say, sparrows) will only mate with other birds. They will not mate with lizards. So no mating-connection will form between a bird and a lizard. So, an account of a network based on the mating habits of birds is a form of weak connectivism. The structure and shape of the network depends on the nature of its constituent parts.

By contrast, if you talk about network formation without reference to the nature of the things connecting, that’s strong connectivism. If you simply think, for example, of the way any two atoms interact, or the way any two animals interact, then you’re talking about the nature of connections abstractly. That’s strong connectivism.

No account of connectivism is purely strong connectivism or purely weak connectivism. All descriptions are a combination of both. Some descriptions rely more on the nature of the entities being connected, and so we call those examples of weak connectivism. Others emphasize more the nature of connections generally, and we can call that strong connectivism.

Footnotes

77 David T. Jones. A question (or two) on the similarity of “neuronal” and “networked” knowledge. The Weblog of (a) David Jones, March 5, 2011. http://davidtjones.wordpress.com/2011/03/05/a-question-or-two-on-the-similarity-of-neuronal-and-networked-knowledge/

Moncton, February 27, 2011

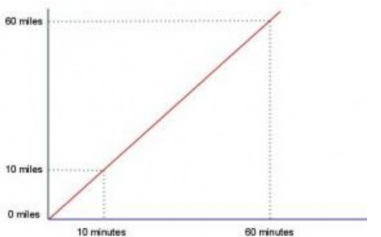

The Personal Network Effect

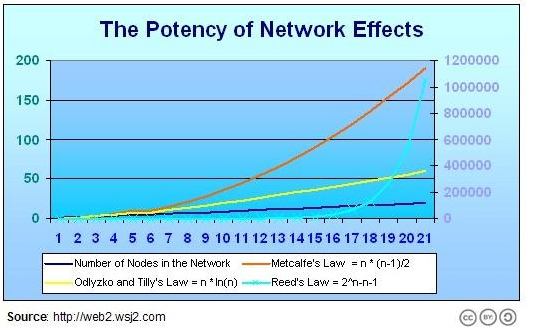

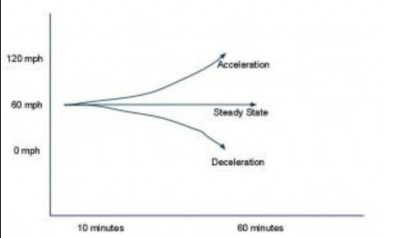

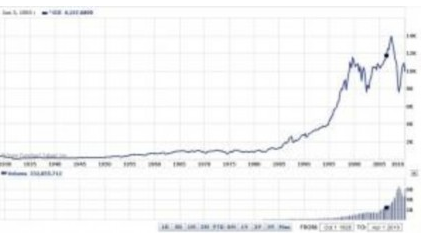

The presumption in the design of most networks is that the value of the network increases with the number of nodes in the network. This is known as the Network Effect, a term that was coined by Robert Metcalfe78 the founder of Ethernet.

79

79

It is therefore tempting to suggest that a similar sort of thing holds for members of the network, that the value of the network is increased the more connections a person has to the network. This isn’t the case.

Each connection produces value to the person. But the relative utility of the connection – that is, its value compared to the value that has already been received elsewhere – decreases after a certain point has been reached.

The reason for this is that value is derived from semantic relevance. Information is semantically relevant only if it is meaningful to the person receiving it (indeed, arguably, it must be semantically relevant to be considered information at all; if it is not meaningful, then it is just static or noise).

Semantic relevance is the result of a combination of factors (which may vary with time and with the individual), according to whether the information is:

-

new to the receiver (cf. Fred Dretske Knowledge and the Flow of Information)

-

salient to the receiver (there are different types of salience: perceptual salience, rule salience, semiotic salience, etc)

-

timely, that is, the information arrives at an appropriate time (before the event it advertises, for example) – this does not mean ‘soonest’ or ‘right away’

-

utile, that is, whether it can be used, whether it is actionable

-

cognate, that is, whether it can be understood by the receiver

-

true, that is, the information is consistent with the belief set of the receiver

-

trusted, that is, comes from a reliable source

-

contiguous, that is, whether the information is flowing fast enough, or as a sufficiently coherent body

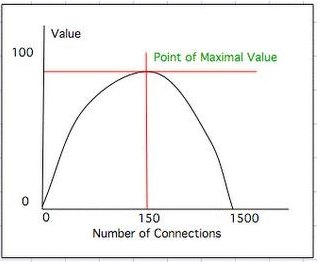

Because of these conditions, the value of each new piece of information, on average, will decrease relative to its predecessors. At a certain point, the value of the new information will be such that it actually detracts from the value of the information already received (by, say, blocking it, distracting one’s attention from it, contradicting it, and the like).

For example, suppose someone tells you that the house is on fire. This is very relevant information, and quite useful to you. Then another person tells you on fire. It’s useful to have confirmation, but clearly not as useful as the first notice. Then a third and a fourth and a fifth and you want to tell people to shut up so you can hear the next important bit of information, namely, how to get out.

This is the personal network effect. In essence, it is the assertion that, for any person at any given time, a certain finite number of connections to other members of the network produces maximal value. Fewer connections, and important sources of information may be missing. More connections, and the additional information received begins to detract from the value of the network.

Most people can experience the personal network effect for themselves by participating in social networks. One’s Facebook account, for example, is minimally valuable when only a few friends are connected. As the number grows over 100, however, Facebook begins to become as effective as it can be. If you keep on adding friends, however, it begins to become less effective.

This is true not only for Facebook but for networks in general. For any given network, for any given individual in the network, here will be a certain number of connections that produces maximum value for that member in that network.

This has several implications.

First, it means that when designing network applications, it is important to build in constraints that allow people to limit the number of connections they have. This is why the opt-in networks such as Facebook produce more value per message than open networks such as email.

Imagine what Twitter would be like is anyone could send you a message! The value in Twitter lies in the user being able to restrict incoming messages to a certain set of friends.

Second, it provides the basis for a metric describing what will constitute valuable communications in a network. Specifically, we want out communications to be new, salient, utile, timely, cognate, true and contiguous.

Third, it demonstrates that there is no single set of best connections. A connection that is very relevant to one person might not be relevant to me at all. This may be because we have different interests, different world views, or speak different languages. But even if we have exactly the same needs and interests, we may get the same information from different sources. By the time your source gets to me, the ‘new’ information it gave you might be very ‘old’ to me.

We see this phenomenon is web communities. Dave Warlick80today posted a link to a video81 produced by Michael Wesch’s Cultural Anthropology students at Kansas State University.

Warlick obviously does not read OLDaily because I linked to the site two weeks ago.82 Warlick credits John Moranski, a school librarian from Auburn High School and Middle School in Auburn, Illinois (no link, which means he probably told him about it in person or by email).

Warlick’s link, therefore, is of little value to me; it’s old news. However, to many of his readers (specifically, those who don’t read me), this will be new. And hence he is a valuable part of their network.

Now here is the important part: the people who read Warlick don’t need to read me (at least with respect to this link). They are getting the same information either way. There is no particular reason to select one source over another. Warlick may be part of his readers by accident (he is the first ed tech person they read, for example) or he may be more semantically relevant to them for other reasons: he is a folksy storyteller, he writes in a simple vocabulary, they have met him personally and trust him, whatever.

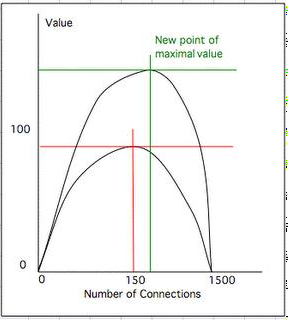

One final point: if we change the way we design the network, we can change the point of maximal value:

It is toward this effect that much of my previous writing about networks has been directed. How can we structure the network in such a way as to maximize the maximal value? I have suggested four criteria: diversity, autonomy, openness, and connectedness (or interactivity).

For example, networks that are more diverse – in which each individual has a different set of connections, for example – produce a greater maximal value than networks that are not.

Compare a community of people where people only read each other. You can read ten people, say, of a fifty person community, and hear pretty quickly what every person is thinking. But reading an eleventh will produce almost no value at all; you will just be getting the same information you were already getting. Compare this to the value of a connection from outside the community. Now you are reading things nobody else has thought about; you learn new things, and your comments have more value to the community as a whole.

It is valuable to have a certain amount of clustering in a network. This is a consequence of the criterion for semantic relevance. This is that people like Clark are getting at when they talk about the need for a common ground,83 or what Wenger means by a shared domain of interest.84 However, an excessive focus on clustering, on what I have characterized as group criteria, results in a decrease in the semantic relevance of messages from community members.

Footnotes

78 Wikipedia. Robert Metcalfe. Accessed November 4, 2007. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Metcalfe

79 Dion Hinchcliffe . Web 2.0’s Secret Sauce: Network Effects. Social Computing Magazine. July 15, 2006. http://web2.socialcomputingmagazine.com/web_20s_real_secret_sauce_ network_effects.htm

80 Dave Warlick. Another Amazing Video About Teaching and Learning. 2¢ Worth (weblog). November 4, 2007. http://davidwarlick.com/2cents/?p=1240

81 Michael Wesch. A Vision of Students Today. YouTube (video). October 12, 2007. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dGCJ46vyR9o

82 Stephen Downes. A Vision of Students Today. OLDaily (weblog). October 15, 2007. http://www.downes.ca/post/42024

83 John Black. Creating a Common Ground for URI Meaning Using Socially Constructed Web sites. WWW 2006, May 23-26, 2006, Edinburgh, Scotland. http://www.ibiblio.org/hhalpin/irw2006/jblack.html

84 Etienne Wenger. Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. June, 2006. http://www.ewenger.com/theory/

Moncton, November 4, 2007

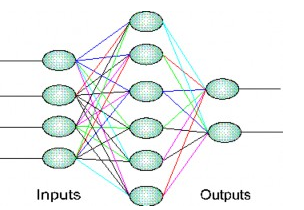

Diagrams and Networks

Responding to Paul Ellerman:85

I was actually pretty careful with the diagrams,86 though on reflection I considered that I should have, for the network diagram, used the standard connectionist (neural network) diagram. See

e.g. this.87

Now in fact there are even in networks people like myself, Will Richardson and Dave Warlick, and they are sometimes called “leaders”. But from the perspective of a network, what makes an entity emphasized in this way is the number and nature of the connections it has, and not any directive import. People like Will, Dave and I stand out because we are well-connected, and not (necessarily) because we are well informed, and certainly not (necessarily) because other people do what we say they should do.

There are in fact two major ways that such people can emerge in a network:

First, as a consequence of the power law phenomenon. This is discussed at length in the discussion of scale-free networks. It is essentially the first-mover advantage. The person who was in the network first is more likely to attract more links. This is also impacted by advertising and self-promotion, phenomena I would not disassociate with the list of names you provide.

Second, as a consequence of the bridging phenomenon. Most networks occur in clusters (prototypes of Wenger’s communities of practice) of like-minded individuals. Philosophers of science, say, or naturalistic poets, or the F1 anti Michael Schumacher hate club. Some people, though, have their feet in two such clusters. They like both beat poetry and the Karate Kid. And so they act as a conduit of information between those two groups, and hence, obtain greater recognition.

In neither case is the person in question a ‘leader’ in anything like the traditional sense. The person does not have ‘followers’ of the usual sort (though they may have fans, but they most certainly don’t have ’staff’ – at least, not as a consequence of their network behaviour). They do not ‘lead’ – they do not tell people what to do. At best and at most, they exemplify the behaviour they would like to see, and at best and at most, they act as a locus of information and conversation.

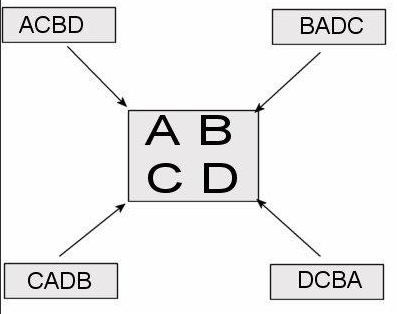

In the diagram, this difference is represented by depicting the ‘traditional’ leader and group as a ‘tree’, with one person connected to a number of people, while at the same time depicting the network as a ‘cluster’, with many people connected to each other.

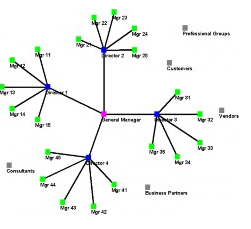

Pushing the model back to the ‘leader’ mode suggested by this item would push the diagram back to a ‘cluster’ or ‘hub and spoke’ model such as this88

which I was anxious to avoid. Not because it doesn’t depict a network (it does, technically, a scale-free network) but because it depicts what I would call a ‘group’ dominated by ‘leaders’, where the leaders have a directive function.

Footnotes

85 Paul Ellerman. Thinking About Networks Part 2. Thoughts on Training, Teaching and Technology. October 2, 2006 http://www.downes.ca/post/35916 Original link (n o longer extant): http://tottandt.wordpress.com/2006/10/02/thinking-about-networks-part- 2/#comment-17

86 Stephen Downes. Groups and Networks. Stephen’s Web (weblog). September 25, 2006. http://www.downes.ca/post/35866

87 E-Sakura System. Images. Probably not the original source, but that’s where I got it. http://www.e-orthopaedics.com/sakura/ Image URL: http://www.e-orthopaedics.com/sakura/images/neural.gif

88 Valdis Krebs. Decision-Making in Organizations. Orgnet.com. 2008. http://orgnet.com/decisions.html

Moncton, October 02, 2006

The Blogosphere is a Mesh

I said

You say “Wrong both descriptively – it’s not what the blogosphere actually looks like… What we are more like … is a mesh, and not a hub-and-spokes network.”

And Mark Berthelemy asked89

I’d be very interested to know the evidence for that statement.

My evidence is that this is what I see, and that if you looked at it from the same perspective, you would see it too.

Yes, you could measure it ’empirically’ via a formal study, but (as I have commented on numerous occasions) you tend to find whatever you’re looking for with such studies.

For example, you could do a Technorati sort of survey and list all of the blogs that link to each other. From this, you could construct a social network graph. And that graph would show what the link cited in this thread shows, that there is a power-law distribution and therefore a hub- and-spoke structure.

And thus you would have found what you were looking for.

And yet, from my perspective – as a hub – I see remarkably little traffic flowing through me. How can this be?

The edublogosphere – and the wider blogosphere – isn’t constructed out of links. The link is merely one metric – a metric that is both easy to count and particularly susceptible to power-law structuring. Links play a role in discovery, but a much smaller role in communication.

We can identify one non-link phenomenon immediately, by looking at almost any blog. After any given post, you’ll see a set of comments. Look at this post of Will Richardson’s90. There’s a set of 25 comments following. And the important thing here is that these comments are communications happening in a social space. They are one-to-many communications. This forms a little cluster of people communicating directly with each other.

Now look at any social network, say del.icio.us.91 This tool was ranked second92 on a list composed mostly of inputs from edubloggers. People link to each other on social networks. Each person keeps his or her own list of ‘buddies’. Here’s mine.93 Empty; I don’t use del.icio.us much. Here’s someone else’s network.94 Edubloggers are using dozens of networks – Friendster, Bebo, Facebook, Myspace, Twitter and more.

But that’s not all. A lot of the chatter I see going on between people I’m connected to is taking place via email, Skype, instant messaging, and similar person-to-person messaging tools.

People put people on their ‘buddy lists’ that they want to call and to hear from. They collect email addresses (and white-list them in their spam filters).

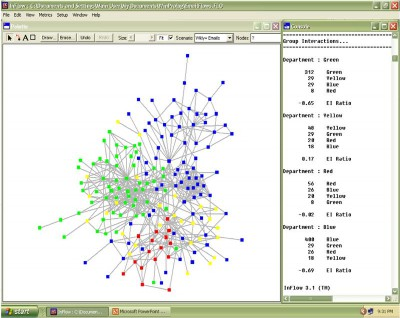

Communications maps are typically clustered.95 Like so:

The result is also observable. You get a clustering of distinct groups of people with particular interests. In the edublogosphere, for example, I can very easily identify the K12 crowd, the corporate e-learning bloggers, the college and university bloggers, the webheads (ESL), and various others.

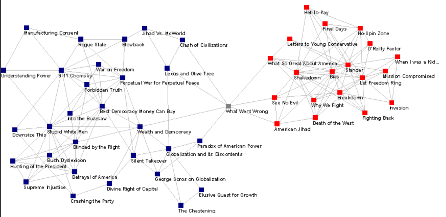

This diagram96 is well known: it charts linkages between books read by bloggers:

This chart is semantic; that is, it depicts what the people talked about. This tells you about the flow of ideas, and not just the physical connections. And when we look at the flow of ideas, we see the characteristic cluster formation.

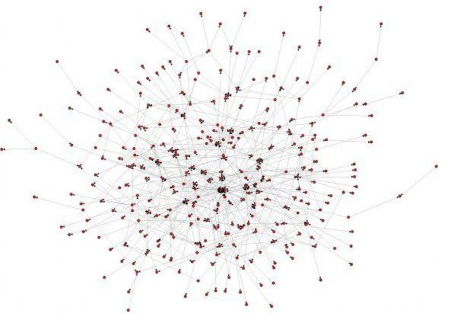

The network of people97 who talk about engineering is, similarly, a cluster:

Another way to spot the blogging network is to look at conference attendance. You can again find these clusters. I don’t have diagrams of the edubloggers, but this conference attendee network of Joi Ito’s is typical:98

If we focus, not on a single physical indicator, but on the set of interactions taken as a whole, it becomes clear that the blogosphere is in fact a cluster-style network, and not a hub-and-spoke network. Bloggers form communities among themselves and communicate using a variety of tools, of which their blogs constitute only one.

Footnotes

89 Mark Berthelemy. Comment to Stephen Downes, Top Edublogs – August 2007. August 20, 2007. http://www.downes.ca/post/41338

90 Will Richardson. The Future of Teaching. Weblogg-Ed (weblog). August 15, 2007. http://weblogg-ed.com/2007/the-future-of-teaching/

91 Delicious. Website. http://del.icio.us/

92 Jane Hart. Top 100 Tools for Learning. Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies. 2007. http://c4lpt.co.uk/top-tools/top-100-tools/ Original link (no longer extant): http://www.c4lpt.co.uk/recommended/top100.html

93 Downes. Tag Search. Delicious. http://delicious.com/network/Downes

94 Delicious. Peartree4. Tag Search. Was full of links when originally referenced August 20, 2007. http://delicious.com/network/peartree4

95 Valdis Krebs, et.al. Social Network Interaction Will Become… Network Weaving. May, 2007. http://www.networkweaver.blogspot.ca/ Original link no longer extant: http://www.networkweaving.com/blog/2007/05/social-network-interaction-will-become.html

96 Valdis Krebs. Divided We Stand? Orgnet.com (weblog). 2003. http://www.orgnet.com/leftright.html

97 Erik van Bekkum. Visualization of engineering community of practice. Efios (website). October 7, 2006.

98 Joichi Ito. Social Network Diagram for ITO JOICHI. Joi Ito (weblog). August 7, 2002. http://joi.ito.com/weblog/2002/08/07/social- network.html

Moncton, August 20, 2007

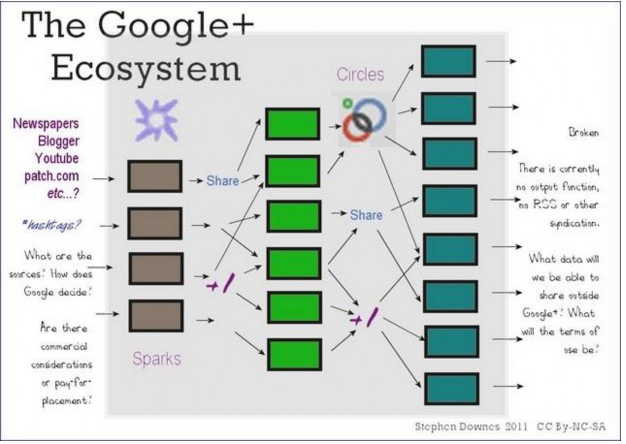

The Google Ecosystem

Posted to Google+

This is an illustration of the Google Plus Ecosystem I created to try to explain the flow of information through Google Plus from its (currently undocumented) sources through to its (currently broken) output.

Moncton, July 9, 2011

What Connectivism Is

Posted to the Connectivism Conference forum99

At its heart, connectivism is the thesis that knowledge is distributed across a network of connections, and therefore that learning consists of the ability to construct and traverse those networks.

It shares with some other theories a core proposition, that knowledge is not acquired as though it were a thing. Hence people see a relation between connectivism and constructivism or active learning (to name a couple).

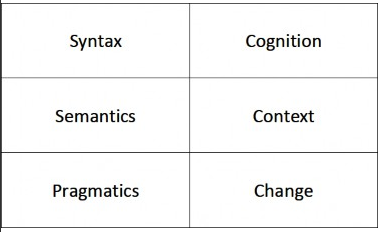

Where connectivism differs from those theories, I would argue, is that connectivism denies that knowledge is propositional. That is to say, these other theories are ‘cognitivist’, in the sense that they depict knowledge and learning as being grounded in language and logic.

Connectivism is, by contrast, ‘connectionist’. Knowledge is, on this theory, literally the set of connections formed by actions and experience. It may consist in part of linguistic structures, but it is not essentially based in linguistic structures, and the properties and constraints of linguistic structures are not the properties and constraints of connectivism or connectivist knowledge.

In connectivism, a phrase like ‘constructing meaning’ makes no sense. Connections form naturally, through a process of association, and are not ‘constructed’ through some sort of intentional action. And ‘meaning’ is a property of language and logic, connoting referential and representational properties of physical symbol systems. Such systems are epiphenomena of (some) networks, and not descriptive of or essential to these networks.

Hence, in connectivism, there is no real concept of transferring knowledge, making knowledge, or building knowledge. Rather, the activities we undertake when we conduct practices in order to learn are more like growing or developing ourselves and our society in certain (connected) ways.

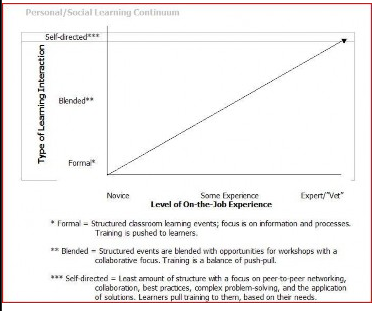

This implies a pedagogy that (a) seeks to describe ‘successful’ networks (as identified by their properties, which I have characterized as diversity, autonomy, openness, and connectivity) and

(b) seeks to describe the practices that lead to such networks, both in the individual and in society (which I have characterized as modeling and demonstration (on the part of a teacher) and practice and reflection (on the part of a learner)).

Response to comments by Tony Forster

A link to my paper ‘An Introduction to Connective Knowledge’100 will help with some of the comments in this post (long, sorry).

Tony writes, “Knowledge is not learning or education, and I am not sure that Constructivism applies only to propositional learning nor that all the symbol systems that we think with have linguistic or propositional characteristics.”101

I think it would be very difficult to draw out any coherent theory of constructivism that is not based on a system with linguistic or propositional characteristics. (or as I would prefer to say, a ‘rule-based representational system’).

Tony continues, “The Constructivist principle of constructing understandings is an important principle because it has direct implications for classroom practice. For me it goes much further than propositional or linguistic symbol systems.”

What is it to ‘construct an understanding’ if it does not involve:

- a representational system, such as language, logic, images, or some other physical symbol set (i.e., a semantics)

- rules or mechanisms for creating entities in that representational system (i.e., a syntax)?Again, I don’t think you get a coherent constructivist theory without one of these. I am always open to be corrected on this, but I would like to see an example.Tony continues, “I am disturbed by your statement that ‘in connectivism, there is no real concept of transferring knowledge, making knowledge, or building knowledge’. I believe that if Connectivism is a learning theory and not just a connectedness theory, it should address transferring understand, making understanding and building understanding.”This gets to the core of the distinction between constructivism and connectivism (in my view, at least).In a representational system, you have a thing, a physical symbol, that stands in a one-to-one relationship with something: a bit of knowledge, an ‘understanding’, something that is learned, etc.In representational theories, we talk about the creation (‘making’ or ‘building’) and transferring of these bits of knowledge. This is understood as a process that parallels (or in unsophisticated theories, is) the creation and transferring of symbolic entities.

Connectivism is not a representational theory. It does not postulate the existence of physical symbols standing in a representational relationship to bits of knowledge or understandings. Indeed, it denies that there are bits of knowledge or understanding, much less that they can be created, represented or transferred.This is the core of connectivism (and its cohort in computer science, connectionism). What you are talking about as ‘an understanding’ is (at a best approximation) distributed across a network of connections. To ‘know that P’ is (approximately) to ‘have a certain set of neural connections’.To ‘know that P’ is, therefore, to be in a certain physical state – but, moreover, one that is unique to you, and further, one that is indistinguishable from other physical states with which it is co- mingled.Tony continues, “Connectivism should still address the hard struggle within of deep thinking, of creating understanding. This is more than the process of making connections.”No, it is not more than the process of making connections. That’s why learning is at once so simple it seems it should be easily explained and so complex that it seems to defy explanation (cf. Hume on this). How can learning – something so basic that infants and animals can do it – defy explanation? As soon as you make learning an intentional process (that is, a process that involves the deliberate creation of a representation) you have made these simple cases difficult, if not impossible, to understand.That’s why this is misplaced: “For example, we could launch into connected learning in a way which forgets the lessons of constructivism and the need for each learner to construct their own mental models in an individualistic way.”The point is: - there are no mental models per se (that is, no systematically constructed rule-based representational systems)

- and what there is (i.e., connectionist networks) is not built (like a model) it is grown (like a plant)

When something like this is said, even basic concepts as ‘personalization’ change completely.

In the ‘model’ approach, personalization typically means more: more options, more choices, more types of tests, etc. You need to customize the environment (the learning) the fit the student.

In the ‘connections’ approach, personalization typically means less: fewer rules, fewer constraints. You need to grant the learner autonomy within the environment.

So there’s a certain sense, I think, in which the understandings of previous theories will not translate well into connectivism, for after all, even basic words and concepts acquire new meaning when viewed from the connectivist perspective.

Response (1) to Bill Kerr

Bill Kerr writes, “It seems that building and metacognition are talked about in George’s version but dismissed or not talked about in Stephen’s version.”

Well, it’s kind of like making friends.

George talks about deciding what people make useful friends, how to make connections with those friends, building a network of those friends.

I talk about being open to ideas, communicating your thoughts and ideas, respecting differences

and letting people live their lives.

Then Bill comes along and says that George is talking about making friends but Stephen just ignores it.

Bill continues, “Either the new theory is intended to replace older theories… Or, the new theory is intended to complement older theories. By my reading, Stephen is saying the former and George is saying the latter but I’m not sure.”

We want to be more precise.

Any theory postulates the existence of some entities and the non-existence of others. The most celebrated example is Newton’s gravitation, which postulated the existence of ‘mass’ and the non-existence of ‘impetus’.

I am using the language of ‘mass’. George, in order to make his writing more accessible, (sometimes) uses the language of ‘impetus’. (That’s my take, anyways).

Response (2) to Bill Kerr

Bill Kerr writes, “Words / language are necessary to sustain long predictive chains of thought, eg. to sustain a chain or combination of pattern recognition. This is true in chess, for example, where the player uses chess notation to assist his or her memory.”

This is not true in chess.

I once played a chess player who (surprisingly to me) turned out to be far my superior (it was a long time ago). I asked, “how do you remember all those combinations?”

He said, “I don’t work in terms of specific positions or specific sequences. Rather, what I do is to always move to a stronger position, a position that can be seen by recognizing the patterns on the board, seen as a whole.”

See, that’s the difference between a cognitivist theory and a connectionist theory. The cognitivist thinks deeply by reasoning through a long sequence of steps. The non-cognitivist thinks deeply by ‘seeing’ more intricate and more subtle patterns. It is a matter of recognition rather than inference.

That’s why this criticism, “Words / language are necessary to sustain long predictive chains of thought,” begs the question. It is levelled against an alternative that is, by definition, non-linear, and hence, does not produce chains of thought.

Response (3) to Bill Kerr

Bill Kerr writes, “I don’t see how what you are saying is helpful at the practical level, the ultimate test for all theories.”

This is kind of like saying that the theory of gravity would not be true were there no engineers to use it to build bridges.

This is absurd, of course. I am trying to describe how people learn. If this is not ‘practical’, well, that’s not my fault. I didn’t make humans.

In fact, I think there are practical consequences, which I have attempted to detail at length elsewhere,102 and it would be most unfair to indict my own theoretical stance without taking that work into consideration.

I have described, for example, the principles that characterize successful networks in my recent paper103 presented to ITForum (I really like Robin Good’s presentation104 of the paper – much nicer layout and graphics). These follow from the theory I describe and inform many of the considerations people like George Siemens have rendered into practical prescriptions.

And I have also expounded, in slogan form, a basic theory of practice: ‘to teach is to model and demonstrate, to learn is to practice and reflect.’

No short-cuts, no secret formulas, so simple it could hardly be called a theory. Not very original either. That, too, is not my fault. That’s how people teach and learn, in my view.

Which means that a lot of the rest of it (yes, including ‘making meaning’) is either (a) flim- flammery, or (more commonly) (b) directed toward something other than teaching and learning. Like, say power and control.

Bill continues, “Stephen, your position on intentional stance sounds similar to Churchland’s position on eliminative materialism.”105

Quite right, and I have referred to him (Churchland) in some of my other work.

“Other materialist philosophers, such as Dennett, argue that we can discuss in terms of intentional stance106 provided it doesn’t lead to question begging interpretations.”

Well, yes, but this is tricky.

It’s kind of like saying, “Well, for the sake of convenience, we can talk about fairies and pixie dust as though they are the cause of the magical events in our lives.” Call it “the magical stance”.

But now, when I am given a requirement to account for the causal powers of fairies, or when I need to show what pixie dust is made of (at the cost of my theory being incoherent) I am in a bit of a pickle (not a real pickle, of course).

The same thing for “folk psychology” – the everyday language of knowledge and beliefs Dennett alludes to. What happens when these concepts, as they are commonly understood, form the foundations of my theory?

“Knowledge is justified true belief,” says the web page.107 Except, it isn’t. The Gettier problems108 make that pretty clear. So when pressed to answer a question like, ‘what is knowledge’ (as though it could be a thing) my response is something like “it’s a belief we can’t not have.” Like ‘knowing’ where Waldo is in the picture after we’ve found him. It’s like recognition. And what is ‘a belief’? A certain set of connections in the brain. Except now that these statements entail that there is no particular thing that is ‘a bit of knowledge’ or ‘a belief’.

Yeah, you can talk in terms of knowledge and beliefs. But it requires a lot of groundwork before it becomes coherent.

Bill continues, “Even though we don’t understand ‘constructing meaning’ clearly we can still advise students in certain ways that will help them develop something that they didn’t have before.”

What, like muscles?

Except, they always had muscles.

Better muscles? Well, ok. But then what do I say? “Practice.”

“I think it’s more useful and practical to operate on that basis, for example, Papert’s advice on ‘learning to learn’ which he called mathetics still stands up well.”

But what if they’re wrong? What if they are exactly the wrong advice? Or moreover, what if they have to do with the structures of power and control that have developed in our learning environments, rather than having anything to do with learning at all?

“Play is OK” has to do with power and control, for example. “Play fosters learning” is a different statement, much more controversial, and yet more descriptive, because play is (after all) practice.

“The emotional precedes the cognitive.” Except that I am told by psychologists that “the fundamental principle underlying all of psychology is that the idea – the thought – precedes the emotion.”

And so on. Each of these aphorisms sound credible, but when held up to the light, are not well- grounded. And hence, not practical.

Footnotes

99 George Siemens. Forum. Online Connectivism Conference. February 1, 2007. http://ltc.umanitoba.ca/moodle/mod/forum/discuss.php?d=12#385