Chapter 9: Intelligences Theory

Learning Objectives

- Define and describe the term intelligence.

- Discuss different ways of measuring an individual’s intellectual abilities.

- Describe pros, cons, and nuances of using students’ measures of intelligence for curriculum purposes.

- Explain the controversy relating to differences in intelligence between groups.

Introduction

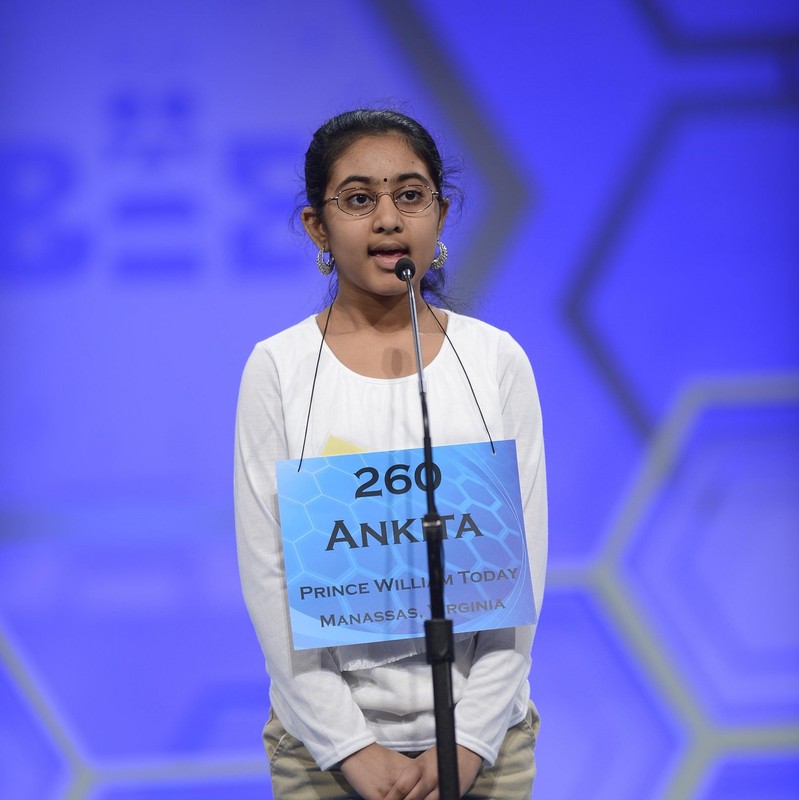

Every year, hundreds of grade school students converge in Washington, D.C., for the annual Scripps National Spelling Bee. The “bee” is an elite event in which children as young as 8 square off to spell words like “cymotrichous” and “appoggiatura.” Most people who watch the bee think of these kids as being “smart” and you likely agree with this description.

What makes a person intelligent? Is it heredity (two of the 2014 contestants in the bee have siblings who have previously won)(National Spelling Bee, 2014a)? Is it interest (the most frequently listed favorite subject among spelling bee competitors is math)(NSB, 2014b)? What are some issues related to using intelligence measurements to describe students’ academic abilities? In this module we will cover these and other fascinating aspects of intelligence. By the end of the module you should be able to define intelligence and discuss some common strategies for measuring intelligence. In addition to discussing issues related to the various intelligence theories, we will also tackle the politically thorny issue of whether there are differences in intelligence between groups such as men and women.

Defining Intelligence

When you think of “smart people,” you likely have an intuitive sense of the qualities that make them intelligent. Maybe you think they have a good memory, or that they can think quickly, or that they simply know a whole lot of information. Indeed, people who exhibit such qualities appear very intelligent. That said, it seems that intelligence must be more than simply knowing facts and being able to remember them.

The question of what constitutes human intelligence is one of the oldest inquiries in psychology. When we talk about intelligence, we typically mean intellectual ability. This broadly encompasses the ability to learn, remember, and use new information, to solve problems, and to adapt to novel situations.

Types of Intelligence

General Intelligence (g factor)

British psychologist Charles Spearman believed intelligence consisted of one general factor, called g (or g factor), which could be measured and compared among individuals. Spearman focused on the commonalities among various intellectual abilities and de-emphasized what made each unique. He based this conclusion on the observation that people who perform well in one intellectual area, such as verbal ability, also tend to perform well in other areas, such as logic and reasoning (Spearman, 1904).

Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence

Other psychologists believe that intelligence is a collection of distinct abilities rather than a single factor. In the 1940s, Raymond Cattell proposed a theory of intelligence that divided general intelligence into two components: crystallized intelligence and fluid intelligence (Cattell, 1963).

Crystallized intelligence is acquired knowledge from education, experiences, and skills gained over time. When you learn, remember, and recall information, you are using crystallized intelligence. You use crystallized intelligence all the time in your coursework by demonstrating that you have mastered the information covered in the course. Crystallized intelligence increases with age as people learn more facts and concepts. Some examples of crystallized intelligence follows:

- Knowing historical facts or vocabulary words

- Solving math problems using learned formulas

- Giving directions in your hometown

- Using prior business experience to manage a new project.

- Reading comprehension and understanding complex texts.

Fluid intelligence encompasses the ability to solve brand-new, complex problems. Fluid intelligence helps you tackle complex, abstract challenges in unfamiliar contexts in daily life. For example, navigating home after being detoured onto an unfamiliar route because of road construction would draw upon your fluid intelligence. Another example might also include the following:

- Figuring out how to fix a broken device without instructions.

- Finding your way around in a place you have never been before

- Solving a new puzzle without instructions.

- Recognizing patterns in a sequence of numbers.

Other theorists and psychologists believe intelligence should be defined more practically. For example, what types of behaviors help you get ahead in life? Which skills promote success? Think about this for a moment. Being able to recite all 44 presidents of the United States in order is an excellent party trick, but will knowing this make you a better person?

Triarchic Theory of Intelligence

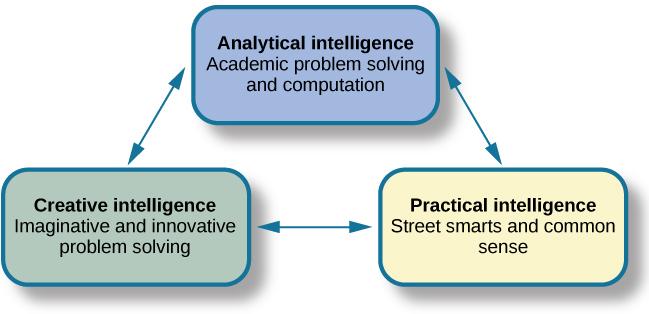

Robert Sternberg developed another theory of intelligence, which he titled the triarchic theory of intelligence because it sees intelligence as comprised of three parts (Sternberg, 1988): practical, creative, and analytical intelligence (Figure 9.2).

As Sternberg proposed, practical intelligence is sometimes compared to “street smarts.” Being practical means you find solutions that work in your everyday life by applying knowledge based on your experiences. This type of intelligence appears to be separate from the traditional understanding of IQ; individuals who score high in practical intelligence may or may not have comparable scores in creative and analytical intelligence (Sternberg, 1988).

This story about the 2007 Virginia Tech shootings illustrates both high and low practical intelligences. During the incident, one student left her class to go get a soda in an adjacent building. She planned to return to class, but when she returned to her building after getting her soda, she saw that the door she used to leave was now chained shut from the inside. Instead of thinking about why there was a chain around the door handles, she went to her class’s window and crawled back into the room. She thus potentially exposed herself to the gunman. Thankfully, she was not shot. On the other hand, a pair of students was walking on campus when they heard gunshots nearby. One friend said, “Let’s go check it out and see what is going on.” The other student said, “No way, we need to run away from the gunshots.” They did just that. As a result, both avoided harm. The student who crawled through the window demonstrated some creative intelligence but did not use common sense. She would have low practical intelligence. The student who encouraged his friend to run away from the sound of gunshots would have much higher practical intelligence.

Analytical intelligence is closely aligned with academic problem-solving and computations. Sternberg says that analytical intelligence is demonstrated by an ability to analyze, evaluate, judge, compare, and contrast. When reading a classic novel for literature class, for example, it is usually necessary to compare the motives of the book’s main characters or analyze the story’s historical context. In a science course such as anatomy, you must study how the body uses various minerals in different human systems. In developing an understanding of this topic, you are using analytical intelligence. When solving a challenging math problem, you would apply analytical intelligence to analyze different aspects of the problem and then solve it section by section.

Creative intelligence is marked by inventing or imagining a solution to a problem or situation. Creativity in this realm can include finding a novel solution to an unexpected problem or producing a beautiful work of art or a well-developed short story. Imagine for a moment that you are camping in the woods with some friends and realize you’ve forgotten your camp coffee pot. The person in your group who can successfully brew coffee for everyone would be credited with having higher creative intelligence.

Multiple Intelligences

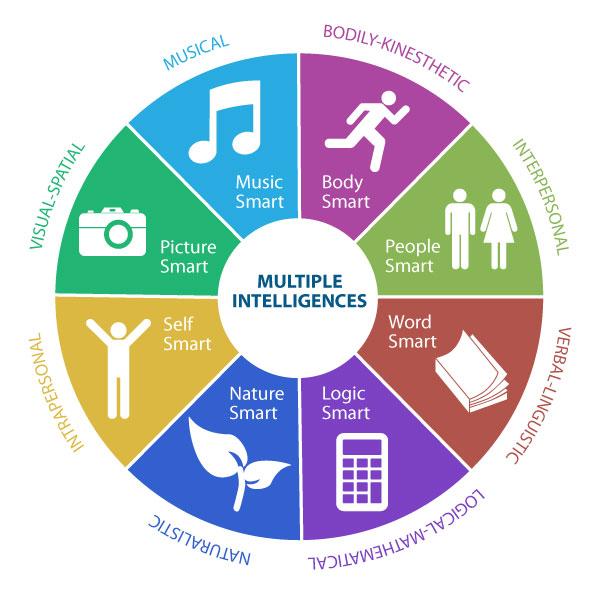

Multiple Intelligences Theory was developed by Howard Gardner, a Harvard psychologist and former student of Erik Erikson. Gardner’s theory, which has been refined for more than 30 years, is a more recent development among theories of intelligence. In Gardner’s theory, each person possesses at least eight intelligences. (See Figure 9.3 below for a visual of these eight intelligences.)

Among these eight intelligences, a person typically excels in some and falters in others (Gardner, 1983). See Table 1 below for a more thorough description of each form of intelligence.

Table 1: Characteristics of the Eight Multiple Intelligences and Corresponding Careers

| Intelligence Type | Characteristics | Representative Career |

| Linguistic intelligence | Perceives different functions of language, different sounds and meanings of words, may easily learn multiple languages | Journalist, novelist, poet, teacher |

| Logical-mathematical intelligence | Capable of seeing numerical patterns, strong ability to use reason and logic | Scientist, mathematician |

| Musical intelligence | Understands and appreciates rhythm, pitch, and tone; may play multiple instruments or perform as a vocalist | Composer, performer |

| Bodily kinesthetic intelligence | High ability to control the movements of the body and use the body to perform various physical tasks | Dancer, athlete, athletic coach, yoga instructor |

| Spatial intelligence | Ability to perceive the relationship between objects and how they move in space | Choreographer, sculptor, architect, aviator, sailor |

| Interpersonal intelligence | Ability to understand and be sensitive to the various emotional states of others | Counselor, social worker, salesperson |

| Intrapersonal intelligence | Ability to access personal feelings and motivations, and use them to direct behavior and reach personal goals | Key component of personal success over time |

| Naturalist intelligence | High capacity to appreciate the natural world and interact with the species within it | Biologist, ecologist, environmentalist |

Importantly, Gardner’s theory is relatively new and needs additional research to establish empirical support better although developing traditional measures of Gardner’s intelligences would be extremely difficult (Furnham, 2009; Despite their being a strong belief in MI, a vast number of researchers assert there is no valid evidence supporting the idea that individuals have separate brain-based intelligences that vary in strength (Waterhouse, 2023). However, Gardner’s ideas challenged the traditional notion of intelligence to include a wider variety of abilities.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence encompasses the ability to understand the emotions of yourself and others (see Figure 9.4), show empathy, understand social relationships and cues, regulate your emotions, and respond in culturally appropriate ways (Parker, Saklofske, & Stough, 2009).

People with high emotional intelligence typically have well-developed social skills. Some researchers, including Daniel Goleman, the author of Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ, argue that emotional intelligence is a better predictor of success than traditional intelligence (Goleman, 1995). However, emotional intelligence has been widely debated, with researchers pointing out inconsistencies in how it is defined and described, as well as questioning results of studies on a subject that is difficult to measure and study empirically (Locke, 2005; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2004). (Note: Gardner’s inter- and intrapersonal intelligences are often combined into a single type of Emotional Intelligence.)

Multicultural Perspectives of Intelligence

Intelligence can also have different meanings and values in different cultures. If you live on a small island, where most people get their food by fishing from boats, it would be important to know how to fish and how to repair a boat. If you were an exceptional angler, your peers would probably consider you intelligent. If you were also skilled at repairing boats, your intelligence might be known across the whole island. Think about your own family’s culture. How do they conceptualize intelligence?

What values are important for Latino families? Italian families? In Irish families, hospitality and telling an entertaining story are marks of the culture. If you are a skilled storyteller, other Irish culture members will likely consider you intelligent.

Some cultures place a high value on working together as a collective. In these cultures, the importance of the group supersedes the importance of individual achievement. When you visit such a culture, how well you relate to the values of that culture exemplifies your cultural intelligence, sometimes referred to as cultural competence.

Measuring Intelligence

Alfred Binet is best known for formally pioneering the measurement of intellectual ability. Binet was fascinated by individual differences in intelligence. For instance, he blindfolded chess players and saw that some of them could continue playing using only their memory to remember the many positions of the pieces (Binet, 1894). Binet was particularly interested in intelligence development, a fascination that led him to closely observe children in the classroom setting.

Along with his colleague Theodore Simon, Binet created a test of children’s intellectual capacity. They created individual test items that should be answerable by children of given ages. For instance, a three-year-old child should be able to point to her mouth and eyes, a nine-year-old should be able to name the months of the year in order, and a twelve-year-old should be able to name sixty words in three minutes. Their assessment became the first “IQ test.”

Sample IQ Questions

1. Which of the following is the most similar to 1313323?

A. ACACCBC

B. CACAABC

C. ABABBCA

D. ACACCDC

2. Jenny has some chocolates. She eats two and gives half of the remainder to Lisa. If Lisa has six chocolates, how many chocolates does Jenny have in the beginning?

A. 6

B. 12

C. 14

D. 18

Which of the following items is not like the others in the list?

duck, raft, canoe, stone, rubber ball

A. Duck

B. Canoe

C. Stone

D. Rubber ball

What do steam and ice have in common?

A. They can both harm skin

B. They are both made from water

C. They are both found in the kitchen

D. They are both the products of water at extreme temperatures

Answers: 1)A; 2)C; 3)Stone; 4)D is the most sophisticated answer

“IQ” or “intelligence quotient” is a name given to the score of the Binet-Simon test. The score is derived by dividing a child’s mental age (the score from the test) by their chronological age to create an overall quotient. These days, the phrase “IQ” does not apply specifically to the Binet-Simon test and is generally used to denote intelligence or a score on any intelligence test. In the early 1900s, the Binet-Simon test was adapted by a Stanford professor named Lewis Terman to create what is, perhaps, the most famous intelligence test in the world, the Stanford-Binet (Terman, 1916).

The significant advantage of this new test was that it was standardized to US populations.. Based on a large sample of children, Terman could plot the scores in a normal distribution, shaped like a “bell curve” (see Figure 9.6). To understand a normal distribution, think about the height of people. Most people are average in height with relatively fewer being tall or short, and fewer still being extremely tall or extremely short. Terman (1916) laid out intelligence scores exactly the same way, allowing for easy and reliable categorizations and individual comparisons.

Looking at another modern intelligence test—the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)—can provide clues to a definition of intelligence itself. Motivated by several criticisms of the Stanford-Binet test, psychologist David Wechsler sought to create a superior measure of intelligence. He was critical of how the Stanford-Binet relied so heavily on verbal ability and was also suspicious of using a single score to capture all of intelligence. Wechsler created a test to address these issues that tapped various intellectual abilities. This understanding of intelligence—that it is made up of a pool of specific abilities—is a notable departure from Spearman’s concept of general intelligence. The WAIS assesses people’s ability to remember, compute, understand language, reason well, and process information quickly (Wechsler, 1955).

Flynn Effect

One interesting by-product of measuring intelligence for so many years is that we can chart changes over time. It might seem strange to you that intelligence can change over the decades, but that appears to have happened over the last 80 years as we have been measuring this topic. Here’s how we know: IQ tests have an average score of 100. When new waves of people are asked to take older tests, they tend to outperform the original sample from years ago, when the test was normed. This gain is known as the “Flynn Effect,” named after James Flynn, the researcher who first identified it (Flynn, 1987). Several hypotheses have been put forth to explain the Flynn Effect, including better nutrition (healthier brains!), greater general familiarity with testing, and more visual stimuli. Today, there is no perfect agreement among psychological researchers with regard to the causes of increases in average scores on intelligence tests. Perhaps if you choose a career in psychology, you will be the one to discover the answer!

Effect of Mindset on Intelligence

There is one last point that is important to bear in mind about intelligence. It turns out that the way an individual thinks about his or her own intelligence is also important because it predicts performance. Researcher Carol Dweck has made a career out of looking at the differences between high IQ children who perform well and those who do not, so-called “underachievers.” Among her most interesting findings is that it is not gender or social class that sets apart the high and low performers. Instead, it is their mindset. The children who believe that their abilities in general—and their intelligence specifically—is a fixed trait tend to underperform. By contrast, kids who believe that intelligence is changeable and evolving tend to handle failure better and perform better (Dweck, 1986). Dweck refers to this as a person’s “mindset” and having a growth mindset appears to be healthier.

The research on mindset is interesting, but there can also be a temptation to interpret it as suggesting that every human has an unlimited potential for intelligence and that becoming smarter is only a matter of positive thinking. There is some evidence that genetics is an important factor in the intelligence equation. For instance, a number of studies on genetics in adults have yielded the result that intelligence is largely, but not totally, inherited (Bouchard,2004). Having a healthy attitude about the nature of smarts and working hard can both definitely help intellectual performance, but it also helps to have the genetic leaning toward intelligence.

Bias and Group Differences

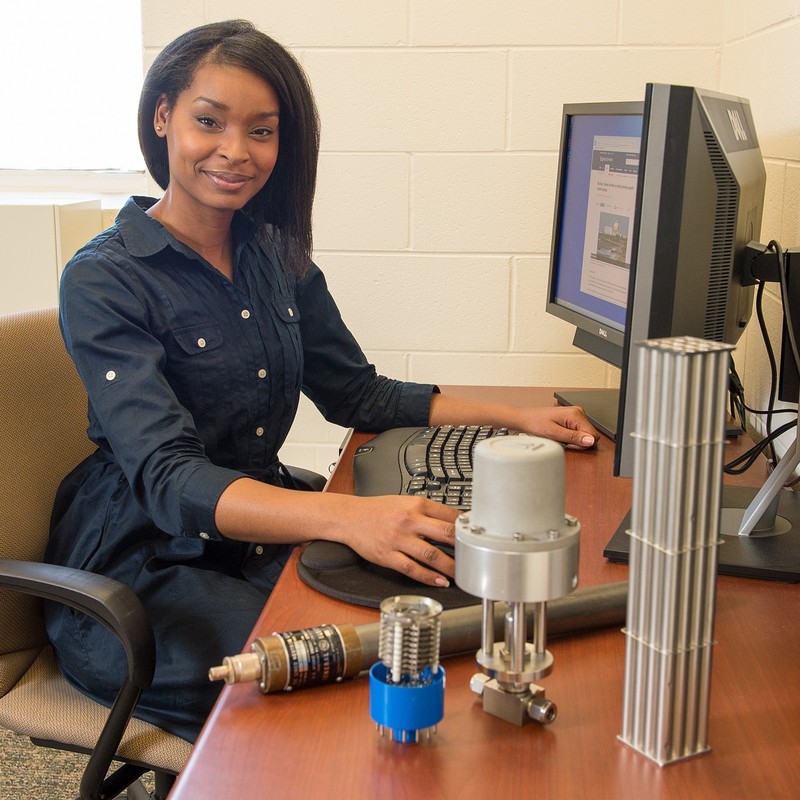

Carol Dweck’s research on the mindset of children also brings one of the most interesting and controversial issues surrounding intelligence research to the fore: group differences. From the very beginning of the study of intelligence, researchers have wondered about differences between groups of people such as men and women. With regards to potential differences between the sexes some people have noticed that women are under-represented in certain fields. In 1976, for example, women comprised just 1% of all faculty members in engineering (Ceci, Williams & Barnett, 2009).

Even today, women comprise between 3% and 15% of all faculty in math-intensive fields at the 50 top universities. This phenomenon could be explained in many ways: it might be the result of inequalities in the educational system, it might be due to differences in socialization wherein young girls are encouraged to develop other interests, it might be the result of that women are—on average—responsible for a larger portion of childcare obligations and therefore make different types of professional decisions, or it might be due to innate differences between these groups, to name just a few possibilities. The possibility of innate differences is the most controversial because many people see it as either the product of or the foundation for sexism. In today’s political landscape, it is easy to see that asking certain questions such as “Are men smarter than women?” would be inflammatory. In a comprehensive review of research on intellectual abilities and sex, Ceci and colleagues (2009) argue against the hypothesis that biological and genetic differences account for much of the sex differences in intellectual ability. Instead, they believe that a complex web of influences ranging from societal expectations to test-taking strategies to individual interests account for many of the sex differences found in math and similar intellectual abilities.

A more interesting question, and perhaps a more sensitive one, might be to inquire in which ways men and women might differ in intellectual ability, if at all. That is, researchers should not seek to prove that one group or another is better but might examine how they differ and offer explanations for any differences that are found. Researchers have investigated sex differences in intellectual ability. In a review of the research literature, Halpern (1997) found that women appear, on average, superior to men in fine motor skills, acquired knowledge, reading comprehension, decoding non-verbal expression, and generally have higher grades in school. Men, by contrast, appear, on average, superior to women on measures of fluid reasoning related to math and science, perceptual tasks that involve moving objects, and tasks that require transformations in working memory, such as mental rotations of physical spaces. Halpern also notes that men are disproportionately represented on the low end of cognitive functioning, including in intellectual disability, dyslexia, and attention deficit disorders (Halpern, 1997).

Other researchers have examined various explanatory hypotheses for why sex differences in intellectual ability occur. Some studies have provided mixed evidence for genetic factors while others point to evidence for social factors (Neisser, et al, 1996; Nisbett, et al., 2012). One interesting phenomenon that has received research scrutiny is the idea of stereotype threat. Stereotype threat is the idea that mental access to a particular stereotype can have real-world impact on a member of the stereotyped group. In one study (Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999), for example, women who were informed that women tend to fare poorly on math exams just before taking a math test performed worse than a control group who did not hear the stereotype. Research on stereotypes has yielded mixed results, and we are currently uncertain exactly how and when this effect might occur. One possible antidote to stereotype threat, at least in the case of women, is to make a self-affirmation (such as listing positive personal qualities) before the threat occurs. In one study, for instance, Martens and her colleagues (2006) had women write about personal qualities that they valued before taking a math test. The affirmation largely erased the effect of stereotype by improving math scores for women relative to a control group but similar affirmations had little effect for men (Martens, Johns, Greenberg, & Schimel, 2006).

These types of controversies compel many laypeople to wonder if there might be a problem with intelligence measures. It is natural to wonder if they are somehow biased against certain groups. Psychologists typically answer such questions by pointing out that bias in the testing sense of the word is different than how people use the word in everyday speech. Common use of bias denotes a prejudice based on group membership. Scientific bias, on the other hand, is related to the psychometric properties of the test such as validity and reliability. Validity is the idea that an assessment measures what it claims to measure and that it can predict future behaviors or performance. To this end, intelligence tests are not biased because they are fairly accurate measures and predictors. There are, however, real biases, prejudices, and inequalities in the social world that might benefit some advantaged group while hindering some disadvantaged others.

Conclusion

Although you might not be able to spell “esquamulose” or “staphylococci”, you might not even know what they mean, you don’t need to count yourself out in the intelligence department. Now that we have examined intelligence in depth, we can return to our intuitive view of those students who compete in the National Spelling Bee. Are they smart? Certainly, they seem to have high verbal intelligence. There is also the possibility that they benefit from either a genetic boost in intelligence, a supportive social environment, or both. Watching them spell difficult words, we also do not know much about them. We cannot tell, for instance, how emotionally intelligent they are or how they might use bodily-kinesthetic intelligence. This highlights the fact that intelligence is a complicated issue. Fortunately, psychologists continue to research this fascinating topic, and their studies continue to yield new insights.

External Links to Learning

- Developing Emotional Intelligence (for children ages 4-12) (OER Commons)

- Multiple Intelligences Theory: Widely Used, Yet Misunderstood (Edutopia)

- Harvard researcher says the most emotionally intelligent people have these 12 traits. Which do you have? (Goleman, 2021)

- See the Interactive CASEL Wheel (See about CASEL)

- Intelligence is Fixed (Center for Educational Research)

- Cultural Perceptions of Human Intelligence (Cocodia, 2014)

- Finding the Next Einstein | Psychology Today (blog) An excellent blog discussing many of the most interesting issue related to intelligence

- Controversy of Intelligence: Crash Course Psychology #23 (YouTube Video)-Hank Green gives a fun and interesting overview of the concept of intelligence in this installment of the Crash Course series.

Self-Reflection & Critical Thinking

- What about the intelligence theory surprises you?

- What intelligence theory did you find most compelling? Why?

- How does knowing about intelligence theory impact you as a learner? Your perception of other learners?

- What are some practical teaching implications of intelligence theory?

- How does intelligence theory inform assessment practices?

- Define intelligence in your own words in a way that reflects its complex and multifaceted nature.

- Construct a model of intelligence to reflect your understanding of its complex nature.

This chapter was remixed from Biswas-Diener, R. (2025). Intelligence. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/ncb2h79v

This chapter was remixed from Spielman, R. M., Dumper, K., Jenkins, W., Lacombe, A., Lovett, M., & Perlmutter, M. (n.d.). What are intelligence and creativity? In Psychology. Retrieved from http://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.75:llWPi2c1@5/What-Are-Intelligence-and-Creativity

Media Attributions

- A participant in the Scripps National Spelling Bee © Scripps National Spelling Bee is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- Three types of intelligence © Sternberg, 1988

- Multiple intelligences theory proposed by Gardner © Sajaganesandip is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Emotional Intelligence © Matthiessen, V., Eklund, P., & Choucair, S. is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Alfred Binet is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bell Curve © Noba is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Women account for a disproportionately small percentage of those employed in math-intensive career fields such as engineering. © Argonne National Laboratory is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license