Incorporation of the Bill of Rights

OpenStax and Lumen Learning; Collected works; and Tom Rozinski

3.1 Introduction to Civil Liberties

Recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations across the nation provide an example of the freedom of assembly protected by the Bill of Rights. This right may now be in jeopardy as bills in several state legislatures threaten peaceful gatherings and even shield citizens who attack such protesters. Fights like this—in the streets, courts, legislatures, and public opinion—are hardly unique in U.S. history. In fact, they are the main driver of political change. The COVID-19 pandemic offers new examples that involve real and perceived infringement on the rights of individuals: to mingle unmasked, to gather in close proximity, or even to assemble at all.[1]

The framers of the Constitution wanted a government that would not repeat the abuses of individual liberties and rights that caused them to declare independence from Britain. However, laws and other “parchment barriers” (or written documents) alone have not protected freedoms over the years; instead, citizens have learned the truth of the old saying (often attributed to Thomas Jefferson but actually said by Irish politician John Philpot Curran), “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” The actions of ordinary citizens, lawyers, and politicians have been at the core of a vigilant effort to protect constitutional liberties.

But what are those freedoms? And how should we balance them against the interests of society and other individuals? These are the key questions we will tackle in this chapter.

3.2 What Are Civil Liberties?

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define civil liberties and civil rights

- Describe the origin of civil liberties in the U.S. context

- Identify the key positions on civil liberties taken at the Constitutional Convention

- Explain the Civil War origin of concern that the states should respect civil liberties

The U.S. Constitution—in particular, the first ten amendments that form the Bill of Rights—protects the freedoms and rights of individuals. It does not limit this protection just to citizens or adults; instead, in most cases, the Constitution simply refers to “persons,” which over time has grown to mean that even children, visitors from other countries, and immigrants—permanent or temporary, legal or undocumented—enjoy the same freedoms when they are in the United States or its territories as adult citizens do. So, whether you are a Japanese tourist visiting Disney World or someone who has stayed beyond the limit of days allowed on your visa, you do not sacrifice your liberties. In everyday conversation, we tend to treat freedoms, liberties, and rights as interchangeable—similar to how separation of powers and checks and balances are often used synonymously, when, in fact, these are distinct concepts.

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn more about civil rights and liberties in the United States.

Defining Civil Liberties

To be more precise in their language, political scientists and legal experts make a distinction between civil liberties and civil rights, even though the Constitution has been interpreted to protect both. We typically envision civil liberties as limitations on government power, intended to protect freedoms upon which governments may not legally intrude. For example, the First Amendment denies the government the power to prohibit “the free exercise” of religion. This means that neither states nor the national government can forbid people to follow a religion of their choice, even if politicians and judges think the religion is misguided, blasphemous, or otherwise inappropriate. Unlike most of the rest of world at the time, U.S. citizens could even create their own faiths recruit followers to it (subject to the U.S. Supreme Court deeming it a religion), even if both society and government disapprove of its tenets. That said, the way you practice your religion, like any other practice, may be regulated if it impinges on the rights of others. To return to the previous example, religious communities may believe their faith will protect them and loved ones from disease, but they may not have the right to both not vaccinate their children and have those children publicly educated, where they would pose a risk to others. The Eighth Amendment says the government cannot impose “cruel and unusual punishments” on individuals for their criminal acts. Although the definitions of cruel and unusual have expanded over the years, the courts have generally and consistently interpreted this provision as making it unconstitutional for government officials to torture suspects. As we will see later in this chapter, courts are currently debating the degree to which extended solitary confinement and certain forms of capital punishment might count as cruel and unusual.

Civil rights, on the other hand, are guarantees that government officials will treat people equally and that decisions will be made on the basis of merit rather than race, gender, or other personal characteristics. Because of the Constitution’s civil rights guarantee, it is unlawful for any publicly-funded entity, such as a school or state university, or even a landlord or potential landlord to treat people differently based on their race, ethnicity, age, sex, or national origin. In the 1960s and 1970s, many states had separate schools where only students of a certain race or gender were able to study. However, the courts decided that these policies violated the civil rights of students who could not be admitted because of those rules.[2] In 2017, the Trump administration began enacting a policy at border entries in El Paso that entailed separating undocumented parents and children as they entered the United States. They expanded that policy in 2018. Today, the government continues to try to reunite families who were separated during that time.[3]

The idea that Americans—indeed, people in general—have fundamental rights and liberties was at the core of the arguments in favor of their independence. In writing the Declaration of Independence in 1776, Thomas Jefferson drew on the ideas of English philosopher John Locke to express the colonists’ belief that they had certain inalienable or natural rights that no ruler had the power or authority to deny to their subjects. It was a scathing legal indictment of King George III for violating the colonists’ liberties. Although the Declaration of Independence does not guarantee specific freedoms, its language was instrumental in inspiring many of the states to adopt protections for civil liberties and rights in their own constitutions, and in expressing principles of the founding era that have resonated in the United States since its independence. In particular, Jefferson’s words “all men are created equal” became the centerpiece of struggles for the rights of women and minorities (Figure 3.2).

LINKS TO LEARNING

Founded in 1920, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is one of the oldest interest groups in the United States. The mission of this non-partisan, not-for-profit organization is “to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States.” Many of the Supreme Court cases in this chapter were litigated by, or with the support of, the ACLU. The ACLU offers a listing of state and local chapters on their website.

Civil Liberties and The Constitution

The Constitution as drafted in 1787 did not include a Bill of Rights, although the idea of including one was proposed and, after brief discussion, dismissed in the final week of the Constitutional Convention. The framers of the Constitution believed they faced much more pressing concerns than the protection of civil rights and liberties—most notably keeping the fragile union together in the light of internal unrest and external threats.

Moreover, the framers thought that they had adequately covered rights issues in the main body of the document. Indeed, the Federalists did include in the Constitution some protections against legislative acts that might restrict the liberties of citizens, based on the history of real and perceived abuses by both British kings and parliaments as well as royal governors. In Article I, Section 9, the Constitution limits the power of Congress in three ways: prohibiting the passage of bills of attainder, prohibiting ex post facto laws, and limiting the ability of Congress to suspend the writ of habeas corpus.

A bill of attainder is a law that convicts or punishes someone for a crime without a trial, a tactic used fairly frequently in England against the king’s enemies. Prohibition of such laws means that the U.S. Congress cannot simply punish people who are unpopular or who seem to be guilty of crimes. An ex post facto law has a retroactive effect: it can be used to punish crimes that were not crimes at the time they were committed, or it can be used to increase the severity of punishment after the fact.

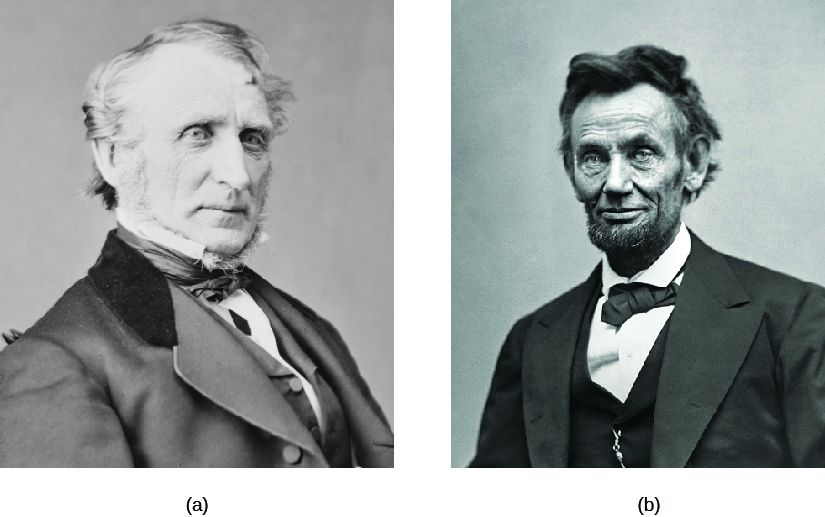

Finally, the writ of habeas corpus is used in our common-law legal system to demand that a neutral judge decide whether someone has been lawfully detained. Particularly in times of war, or even in response to threats against national security, the government has held suspected enemy agents without access to civilian courts, often without access to lawyers or a defense, seeking instead to try them before military tribunals or detain them indefinitely without trial. For example, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln detained suspected Confederate saboteurs and sympathizers in Union-controlled states and attempted to have them tried in military courts, leading the Supreme Court to rule in Ex parte Milligan that the government could not bypass the civilian court system in states where it was operating.[4] In 1919, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes was the lone dissenter in the Abrams v. United States decision that convicted four, young, antiwar activists for pamphleteering against U.S. involvement in the Russian Civil War, which now would be exercised as a clear case of freedom of speech.

During World War II, the Roosevelt administration interned Japanese Americans and had other suspected enemy agents—including U.S. citizens—tried by military courts rather than by the civilian justice system, a choice the Supreme Court upheld in Ex parte Quirin (Figure 3.3).[5] More recently, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the Bush and Obama administrations detained suspected terrorists captured both within and outside the United States and sought to avoid trials in civilian courts, and surveilled U.S. citizens to detect threats. Hence, there have been times in our history when national security issues trumped individual liberties.

Debate has always swirled over these issues. The Federalists reasoned that the limited set of named or enumerated powers of Congress, along with the limitations on those powers in Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, would suffice, and that no separate bill of rights was needed. Writing as Publius in Federalist No. 84, Alexander Hamilton argued that the Constitution was “merely intended to regulate the general political interests of the nation” rather than contend with “the regulation of every species of personal and private concerns.” Hamilton went on to argue that listing some rights might actually be dangerous, because it would provide a pretext for people to claim that rights not included in such a list were not protected. Later, James Madison, in his speech introducing the proposed amendments that would become the Bill of Rights, acknowledged another Federalist argument: “It has been said, that a bill of rights is not necessary, because the establishment of this government has not repealed those declarations of rights which are added to the several state constitutions.”[6] Neither had the Articles of Confederation included a specific listing of rights, even if it was predictable that state governments would differ in what they would tolerate, grant, and prohibit among their citizens.

Anti-Federalists argued that the Federalists’ position was incorrect and perhaps even insincere. The Anti-Federalists believed provisions such as the so-called elastic clause in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution would allow Congress to legislate on matters well beyond those foreseen by the Constitution’s authors. Thus, they held that a bill of rights was necessary. One of the Anti-Federalists, Brutus, whom most scholars believe to be Robert Yates, wrote: “The powers, rights, and authority, granted to the general government by this Constitution, are as complete, with respect to every object to which they extend, as that of any state government—It reaches to every thing which concerns human happiness—Life, liberty, and property, are under its controul [sic]. There is the same reason, therefore, that the exercise of power, in this case, should be restrained within proper limits, as in that of the state governments.”[7] The experience of the past two centuries has suggested that the Anti-Federalists may have been correct in this regard. While the states retain a great deal of importance, the scope and powers of the national government are much broader today than in 1787—likely beyond even the imaginings of the Federalists themselves.

The struggle to have rights clearly delineated and the decision of the framers to omit a bill of rights from the Constitution nearly derailed the ratification process. While some of the states were willing to ratify without any further guarantees, in some of the larger states—New York and Virginia in particular—the Constitution’s lack of specified rights became a serious point of contention. The Constitution could go into effect with the support of only nine states, but the Federalists knew it could not be effective without the participation of the largest states. To secure majorities in favor of ratification in New York and Virginia, as well as Massachusetts, they agreed to consider incorporating provisions suggested by the ratifying states as amendments to the Constitution.

Ultimately, James Madison delivered on this promise by proposing a package of amendments in the First Congress, drawing from the Declaration of Rights in the Virginia state constitution, suggestions from the ratification conventions, and other sources. Each of these were extensively debated in both houses of Congress and, ultimately, proposed as twelve separate amendments for ratification by the states. Ten of the amendments were successfully ratified by the requisite 75 percent of the states and became known as the Bill of Rights (Table 3.1).

FINDING A MIDDLE GROUND

Debating the Need for a Bill of Rights

One of the most serious debates between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists was over the necessity of limiting the power of the new federal government with a Bill of Rights. As we saw in this section, the Federalists believed a Bill of Rights was unnecessary—and perhaps even dangerous to liberty, because it might invite violations of rights that weren’t included in it—while the Anti-Federalists thought the national government would prove adept at expanding its powers and influence and that citizens couldn’t depend on the good judgment of Congress alone to protect their rights.

As George Washington’s call for a bill of rights in his first inaugural address suggested, while the Federalists ultimately had to add the Bill of Rights to the Constitution in order to win ratification, the Anti-Federalists’ fear that the national government might intrude on civil liberties proved to be prescient. In 1798, at the behest of President John Adams during the Quasi-War with France, Congress passed a series of four laws collectively known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws were drafted to allow the president to imprison or deport foreign citizens that he believed were “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States” and to restrict speech and newspaper articles critical of the federal government or its officials. The laws were primarily used against members and supporters of the opposition, the Democratic-Republican Party.

State laws and constitutions protecting free speech and freedom of the press proved ineffective in limiting this new federal power. Although the courts did not decide on the constitutionality of these laws at the time, most scholars believe the Sedition Act, in particular, would be ruled unconstitutional if it had remained in effect. Three of the four laws were repealed in the Jefferson administration, but one—the Alien Enemies Act—remains on the books today. Two centuries later, the issue of free speech and freedom of the press during times of international conflict remains a subject of intense public debate.

Should the government be able to restrict or censor unpatriotic, disloyal, or critical speech in times of international conflict? What about from government whistle-blowers or employees who leak sensitive information? How much freedom should journalists have to report on stories from the perspective of enemies or to repeat propaganda from opposing forces?

Extending The Bill of Rights to The States

In the decades following the Constitution’s ratification, the Supreme Court declined to expand the Bill of Rights to curb the power of the states, most notably in the 1833 case of Barron v. Baltimore.[8] In this case, which dealt with property rights under the Fifth Amendment, the Supreme Court unanimously decided that the Bill of Rights applied only to actions by the federal government, not state or local governments. Explaining the court’s ruling, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote that it was incorrect to argue that “the Constitution was intended to secure the people of the several states against the undue exercise of power by their respective state governments; as well as against that which might be attempted by their [Federal] government.”

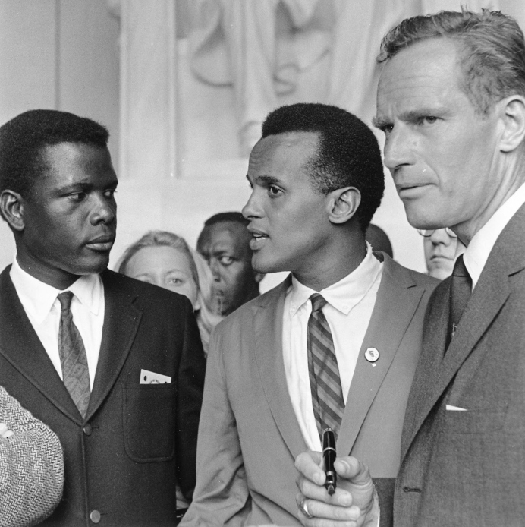

The festering issue of the rights of enslaved persons and the convulsions of the Civil War and its aftermath forced a reexamination of the prevailing thinking about the application of the Bill of Rights to the states. Soon after slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment, state governments—particularly those in the former Confederacy—began to pass “Black codes” that restricted the rights of formerly enslaved people, including the right to hold office, own land, or vote, relegating them to second-class citizenship. Angered by these actions, members of the Radical Republican faction in Congress demanded that the Black codes be overturned. In the short term, they advocated suspending civilian government in most of the southern states and replacing politicians who had enacted these discriminatory laws. Their long-term solution was to propose and enforce two amendments to the Constitution to guarantee the rights of freed men and women. These became the Fourteenth Amendment, which dealt with civil liberties and rights in general, and the Fifteenth Amendment, which protected the right to vote in particular (Figure 3.4). though still not for women or Native Americans.

With the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, the scope and limits of civil liberties became clearer. First, the amendment says, “no State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States,” which is a provision that echoes the privileges and immunities clause in Article IV, Section 2 of the original Constitution ensuring that states treat citizens of other states the same as their own citizens. (To use an example from today, the punishment for speeding by an out-of-state driver cannot be more severe than the punishment for an in-state driver). Legal scholars and the courts have extensively debated the meaning of this privileges or immunities clause over the years, with some arguing that it was supposed to extend the entire Bill of Rights (or at least the first eight amendments) to the states, and others arguing that only some rights are extended. In 1999, Justice John Paul Stevens, writing for a majority of the Supreme Court, argued in Saenz v. Roe that the clause protects the right to travel from one state to another.[9] More recently, Justice Clarence Thomas argued in the 2010 McDonald v. Chicago ruling that the individual right to bear arms applied to the states because of this clause.[10]

The second provision of the Fourteenth Amendment pertaining to the application of the Bill of Rights to the states is the due process clause, which famously reads, “nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Like the Fifth Amendment, this clause refers to “due process,” a term that is interpreted to require both access to procedural justice (such as the right to a trial) as well as the more substantive implication that people be treated fairly and impartially by government officials. Although the text of the provision does not mention rights specifically, the courts have held in a series of cases that due process also implies that there are certain fundamental liberties that cannot be denied by the states. For example, in Sherbert v. Verner (1963), the Supreme Court ruled that states could not deny unemployment benefits to an individual who turned down a job because it required working on the Sabbath.[11]

Beginning in 1897, the Supreme Court has found that various provisions of the Bill of Rights protecting these fundamental liberties must be upheld by the states, even if their state constitutions and laws (and the Tenth Amendment itself) do not protect them as fully as the Bill of Rights does—or at all. This means there has been a process of selective incorporation of the Bill of Rights into the practices of the states: the Constitution effectively inserts parts of the Bill of Rights into state laws and constitutions, even though it doesn’t do so explicitly. When cases arise to clarify particular issues and procedures, the Supreme Court decides whether state laws violate the Bill of Rights and are therefore unconstitutional.

For example, under the Fifth Amendment, a person can be tried in federal court for a felony—a serious crime—only after a grand jury issues an indictment indicating that it is reasonable to try them. (A grand jury is a group of citizens charged with deciding whether there is enough evidence of a crime to prosecute someone.) The Supreme Court has ruled that states don’t have to use grand juries as long as they ensure people accused of crimes are indicted using an equally fair process.

Selective incorporation is an ongoing process. When the Supreme Court initially decided in 2008 that the Second Amendment protects an individual’s right to keep and bear arms, it did not decide then that it was a fundamental liberty the states must uphold as well. It was only in the McDonald v. Chicago case two years later that the Supreme Court incorporated the Second Amendment into state law. Another area in which the Supreme Court gradually moved to incorporate the Bill of Rights regards censorship and the Fourteenth Amendment. In Near v. Minnesota (1931), the Court disagreed with state courts regarding censorship and ruled it unconstitutional except in rare cases.[12]

3.3 Securing Basic Freedoms

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the liberties and rights guaranteed by the first four amendments to the Constitution

- Explain why in practice these rights and liberties are limited

- Explain why interpreting some amendments has been controversial

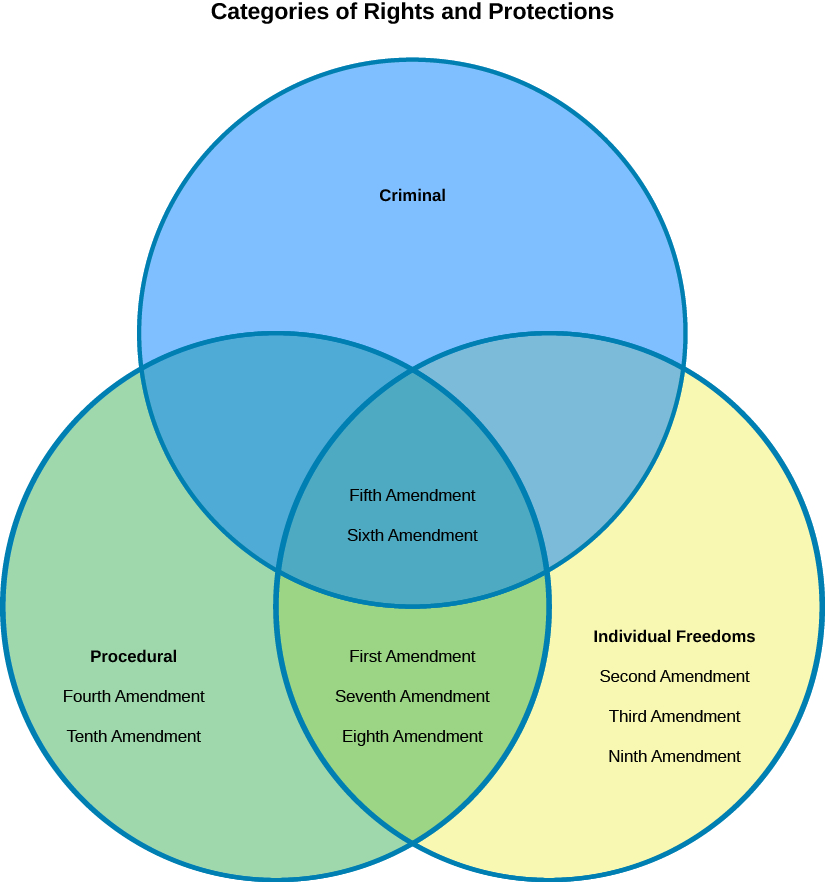

We can broadly divide the provisions of the Bill of Rights into three categories. The First, Second, Third, and Fourth Amendments protect basic individual freedoms; the Fourth (partly), Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth protect people suspected or accused of criminal activity or facing civil litigation; and the Ninth and Tenth, are consistent with the framers’ view that the Bill of Rights is not necessarily an exhaustive list of all the rights people have and guarantees a role for state as well as federal government (Figure 3.5).

The First Amendment

The First Amendment is perhaps the most famous provision of the Bill of Rights. It is arguably also the most extensive, because it guarantees both religious freedoms and the right to express your views in public. Specifically, the First Amendment says:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Given the broad scope of this amendment, it is helpful to break it into its two major parts. The first portion deals with religious freedom. However, it actually protects two related sorts of freedom: first, it protects people from having a set of religious beliefs imposed on them by the government, and second, it protects people from having their own religious beliefs restricted by government authorities.

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn more about freedom of speech.

The first of these two freedoms is known as the establishment clause. Congress is prohibited from creating or promoting a state-sponsored religion (this now includes the states). When the United States was founded, most countries around the world had an established church or religion—an officially sponsored set of religious beliefs and values. In Europe, bitter wars were fought between and within states, often because the established church of one territory was in conflict with that of another. Wars and civil strife were common, particularly between states with Protestant and Catholic churches that had differing interpretations of Christianity. Even today, the legacy of these wars remains, most notably in Ireland, where complications from Brexit have rekindled tensions between a mostly Catholic south and a largely Protestant north that have been simmering for nearly a century.

Many settlers in the United States came to this continent as refugees from such wars; others came to find a place where they could follow their own religion with like-minded people in relative peace. Even if the early United States had wanted to establish a single national religion, the diversity of religious beliefs within and between the colonies would have made this quite impossible. Nonetheless the differences were small; most people were of European origin and professed some form of Christianity (although in private some of the founders, most notably Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, and Benjamin Franklin, held what today would be seen as more pluralistic Unitarian or deistic views). So for much of U.S. history, the establishment clause was not particularly important—the vast majority of citizens were Protestant Christians of some form, and since the federal government was relatively uninvolved in the day-to-day lives of the people, there was little opportunity for conflict. That said, there were some citizenship and office-holding restrictions on Jews within some of the states.

Worry about state sponsorship of religion in the United States began to reemerge in the latter part of the nineteenth century. An influx of immigrants from Ireland and eastern and southern Europe brought large numbers of Catholics. Fearing the new immigrants and their children would not assimilate, states passed laws forbidding government aid to religious schools. New religious organizations, such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Seventh-day Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and many others, also emerged, blending aspects of Protestant beliefs with other ideas and teachings at odds with the more traditional Protestant churches of the era. At the same time, public schooling was beginning to take root on a wide scale. Since most states had traditional Protestant majorities and most state officials were Protestants themselves, the public school curriculum incorporated many Protestant features; at times, these features would come into conflict with the beliefs of children from other Christian sects or from other religious traditions.

The establishment clause today tends to be interpreted a bit more broadly than in the past; it not only forbids the creation of a “Church of the United States” or “Church of Ohio” it also forbids the government from favoring one set of religious beliefs over others or favoring religion (of any variety) over non-religion. Thus, the government cannot promote, say, Islamic beliefs over Sikh beliefs or belief in God over atheism or agnosticism (Figure 3.6).

The key question that faces the courts is whether the establishment clause should be understood as imposing, in Thomas Jefferson’s words, “a wall of separation between church and state.” In a 1971 case known as Lemon v. Kurtzman, the Supreme Court established the Lemon test for deciding whether a law or other government action that might promote a particular religious practice should be allowed to stand.[13] The Lemon test has three criteria that must be satisfied for such a law or action to be found constitutional and remain in effect:

- The action or law must not lead to excessive government entanglement with religion; in other words, policing the boundary between government and religion should be relatively straightforward and not require extensive effort by the government.

- The action or law cannot either inhibit or advance religious practice; it should be neutral in its effects on religion.

- The action or law must have some secular purpose; there must be some non-religious justification for the law.

For example, imagine your state decides to fund a school voucher program that allows children to attend private and parochial schools at public expense; the vouchers can be used to pay for school books and transportation to and from school. Would this voucher program be constitutional?

Let’s start with the secular-purpose prong of the test. Educating children is a clear, non-religious purpose, so the law has a secular purpose. The law would neither inhibit nor advance religious practice, so that prong would be satisfied. The remaining question—and usually the one on which court decisions turn—is whether the law leads to excessive government entanglement with religious practice. Given that transportation and school books generally have no religious purpose, there is little risk that paying for them would lead the state to much entanglement with religion. The decision would become more difficult if the funding were unrestricted in use or helped to pay for facilities or teacher salaries; if that were the case, it might indeed be used for a religious purpose, and it would be harder for the government to ensure that it wasn’t without audits or other investigations that could lead to too much government entanglement with religion.

The use of education as an example is not an accident; in fact, many of the court’s cases dealing with the establishment clause have involved education, particularly public education, because school-age children are considered a special and vulnerable population. Perhaps no subject affected by the First Amendment has been more controversial than the issue of prayer in public schools. Discussion about school prayer has been particularly fraught because in many ways it appears to bring the two religious liberty clauses into conflict with each other. The free exercise clause, discussed below, guarantees the right of individuals to practice their religion without government interference—and while the rights of children are not as extensive in all areas as those of adults, the courts have consistently ruled that the free exercise clause’s guarantee of religious freedom applies to children as well.

At the same time, however, government actions that require or encourage particular religious practices might infringe upon children’s rights to follow their own religious beliefs and thus, in effect, be unconstitutional establishments of religion. For example, a teacher, an athletic coach, or even a student reciting a prayer in front of a class or leading students in prayer as part of the organized school activities constitutes an illegal establishment of religion.[14] Yet a school cannot prohibit voluntary, non-disruptive prayer by its students, because that would impair the free exercise of religion. So although the blanket statement that “prayer in schools is illegal” or unconstitutional is incorrect, the establishment clause does limit official endorsement of religion, including prayers organized or otherwise facilitated by school authorities, even as part of off-campus or extracurricular activities.[15]

But some laws that may appear to establish certain religious practices are allowed. For example, the courts have permitted religiously inspired blue laws that limit working hours or even shutter businesses on Sunday, the Christian day of rest, because by allowing people to practice their (Christian) faith, such rules may help ensure the “health, safety, recreation, and general well-being” of citizens. They have allowed restrictions on the sale of alcohol and sometimes other goods on Sunday for similar reasons. Such laws in Bergen County, New Jersey, and especially its borough of Paramus, shutter many retail stores every Sunday, despite Bergen having one of the largest concentrations of retail space in the nation and five large enclosed shopping malls. While various political figures, including Chris Christie, have proposed repealing the laws, town and county officials have vowed to keep them in place as a “quality of life” element. Many citizens support them, while others cite the difficulty in doing their own shopping and the impact on smaller retailers in their rationale for eliminating the restrictions.

The meaning of the establishment clause has been controversial at times because, as a matter of course, government officials acknowledge that we live in a society with vigorous religious practice where most people believe in God—even if we disagree on what God is. Disputes often arise over how much the government can acknowledge this widespread religious belief. The courts have generally allowed for a certain tolerance of what is described as ceremonial deism, an acknowledgement of God or a creator that generally lacks any substantive religious content. For example, the national motto “In God We Trust,” which appears on our coins and paper money (Figure 3.7), is seen as more an acknowledgment that most citizens believe in God than any serious effort by government officials to promote religious belief and practice. This reasoning has also been used to permit the inclusion of the phrase “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance—a change that came about during the early years of the Cold War as a means of contrasting the United States with the “godless” Soviet Union.

In addition, the courts have allowed some religiously motivated actions by government agencies, such as clergy delivering prayers to open city council meetings and legislative sessions, on the presumption that—unlike school children—adult participants can distinguish between the government’s allowing someone to speak and endorsing that person’s speech. Yet, while some displays of religious codes (e.g., Ten Commandments) are permitted in the context of showing the evolution of law over the centuries (Figure 3.7), in other cases, these displays have been removed after state supreme court rulings. In Oklahoma, the courts ordered the removal of a Ten Commandments sculpture at the state capitol when other groups, including Satanists and the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, attempted to get their own sculptures allowed there.

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn about freedom of religion.

The Free Exercise Clause

The free exercise clause, on the other hand, limits the ability of the government to control or restrict religious practices. This portion of the First Amendment regulates not the government’s promotion of religion, but rather government suppression of religious beliefs and practices. Much of the controversy surrounding the free exercise clause reflects the way laws or rules that apply to everyone might apply to people with particular religious beliefs. For example, can a Jewish police officer whose religious belief, if followed strictly, requires them to observe Shabbat be compelled to work on a Friday night or during the day on Saturday? Or must the government accommodate this religious practice, even if it means the general law or rule in question is not applied equally to everyone?

In the 1930s and 1940s, cases involving Jehovah’s Witnesses demonstrated the difficulty of striking the right balance. In addition to following their church’s teaching that they should not participate in military combat, members refuse to participate in displays of patriotism, including saluting the flag and reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, and they regularly engage in door-to-door evangelism to recruit converts. These activities have led to frequent conflict with local authorities. Jehovah’s Witness children were punished in public schools for failing to salute the flag or recite the Pledge of Allegiance, and members attempting to evangelize were arrested for violating laws against door-to-door solicitation of customers. In early legal challenges brought by Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Supreme Court was reluctant to overturn state and local laws that burdened their religious beliefs.[16] However, in later cases, the court was willing to uphold the rights of Jehovah’s Witnesses to proselytize and refuse to salute the flag or recite the Pledge.[17]

The rights of conscientious objectors—individuals who claim the right to refuse to perform military service on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion—have also been controversial, although many conscientious objectors have contributed service as non-combatant medics during wartime. To avoid serving in the Vietnam War, many people claimed to have a conscientious objection to military service on the basis that they believed this particular war was unwise or unjust. However, the Supreme Court ruled in Gillette v. United States that to claim to be a conscientious objector, a person must be opposed to serving in any war, not just some wars.[18]

Establishing a general framework for deciding whether a religious belief can trump general laws and policies has been a challenge for the Supreme Court. In the 1960s and 1970s, the court decided two cases in which it laid out a general test for deciding similar cases in the future. In both Sherbert v. Verner, a case dealing with unemployment compensation, and Wisconsin v. Yoder, which dealt with the right of Amish parents to homeschool their children, the court said that for a law to be allowed to limit or burden a religious practice, the government must meet two criteria.[19] It must demonstrate both that it had a “compelling governmental interest” in limiting that practice and that the restriction was “narrowly tailored.” In other words, it must show there was a very good reason for the law in question and that the law was the only feasible way of achieving that goal. This standard became known as the Sherbert test. Since the burden of proof in these cases was on the government, the Supreme Court made it very difficult for the federal and state governments to enforce laws against individuals that would infringe upon their religious beliefs.

In 1990, the Supreme Court made a controversial decision substantially narrowing the Sherbert test in Employment Division v. Smith, more popularly known as “the peyote case.”[20] This case involved two men who were members of the Native American Church, a religious organization that uses the hallucinogenic peyote plant as part of its sacraments. After being arrested for possession of peyote, the two men were fired from their jobs as counselors at a private drug rehabilitation clinic. When they applied for unemployment benefits, the state refused to pay on the basis that they had been dismissed for work-related reasons. The men appealed the denial of benefits and were initially successful, since the state courts applied the Sherbert test and found that the denial of unemployment benefits burdened their religious beliefs. However, the Supreme Court ruled in a 6–3 decision that the “compelling governmental interest” standard should not apply; instead, so long as the law was not designed to target a person’s religious beliefs in particular, it was not up to the courts to decide that those beliefs were more important than the law in question.

On the surface, a case involving the Native American Church seems unlikely to arouse much controversy. But because it replaced the Sherbert test with one that allowed more government regulation of religious practices, followers of other religious traditions grew concerned that state and local laws, even ones neutral on their face, might be used to curtail their religious practices. In 1993, in response to this decision, Congress passed a law known as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which was followed in 2000 by the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act after part of the RFRA was struck down by the Supreme Court. In addition, since 1990, twenty-one states have passed state RFRAs that include the Sherbert test in state law, and state court decisions in eleven states have enshrined the Sherbert test’s compelling governmental interest interpretation of the free exercise clause into state law.[21]

However, the RFRA itself has not been without its critics. While it has been relatively uncontroversial as applied to the rights of individuals, debate has emerged about whether businesses and other groups can be said to have religious liberty. In explicitly religious organizations, such as an Orthodox Union congregation or the Roman Catholic Church, it is fairly obvious members have a meaningful, shared religious belief. But the application of the RFRA has become more problematic in businesses and non-profit organizations whose owners or organizers may share a religious belief while the organization has some secular, non-religious purpose.

Such a conflict emerged in the 2014 Supreme Court case known as Burwell v. Hobby Lobby.[22] The Hobby Lobby chain of stores sells arts and crafts merchandise at hundreds of stores and its founder, David Green, is a fundamentalist Christian whose beliefs include opposition to abortion and contraception. Consistent with these beliefs, he used his business to object to a provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare) requiring employer-backed insurance plans to include no-charge access to the morning-after pill, a form of emergency contraception, arguing that this requirement infringed on his conscience. Based in part on the federal RFRA, the Supreme Court agreed 5–4 with Green and Hobby Lobby’s position and said that Hobby Lobby and other closely held businesses did not have to provide employees free access to emergency contraception or other birth control if doing so would violate the religious beliefs of the business’ owners, because there were other less restrictive ways the government could ensure access to these services for Hobby Lobby’s employees (e.g., paying for them directly).

In 2015, state RFRAs became controversial when individuals and businesses that provided wedding services (e.g., catering and photography) were compelled to provide these for same-sex weddings in states where the practice had been newly legalized (Figure 3.8).Proponents of state RFRA laws argued that people and businesses ought not be compelled to endorse practices that their religious beliefs hold to be immoral or indecent. They also indicated concerns that clergy might be compelled to officiate same-sex marriages against their religion’s teachings. Opponents of RFRA laws argued that individuals and businesses should be required, per Obergefell v. Hodges, to serve same-sex marriages on an equal basis as a matter of ensuring the civil rights of gays and lesbian people, just as they would be obliged to cater or photograph an interracial marriage.[23] It should be noted that religious organizations and clergy are not homogeneous in their view of marriage. For example, same-sex marriage is supported by Episcopalians, a sizable number of Methodists, and many leaders in the Jewish and Hindu faiths.[24]

Despite ongoing controversy, however, the courts have consistently found some public interests sufficiently compelling to override the free exercise clause. For example, since the late nineteenth century, the courts have consistently held that people’s religious beliefs do not exempt them from the general laws against polygamy, drug use, or human sacrifice. Yet, the public interest did not trump individual rights during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the Supreme Court overturned California’s ban on indoor gatherings.[25] Other potential acts in the name of religion that are also out of the question are drug use and human sacrifice.

Freedom of Expression

Although the remainder of the First Amendment protects four distinct rights—free speech, press, assembly, and petition—we generally think of these rights today as encompassing a right to freedom of expression, particularly since the world’s technological evolution has blurred the lines between oral and written communication (i.e., speech and press) in the centuries since the First Amendment was written and adopted.

Controversies over freedom of expression were rare until the 1900s, even though government censorship was quite common. For example, during the Civil War, the Union post office refused to deliver newspapers that opposed the war or sympathized with the Confederacy, while allowing pro-war newspapers to be mailed. The emergence of photography and movies, in particular, led to new public concerns about morality, causing both state and federal politicians to censor lewd and otherwise improper content. At the same time, writers became more ambitious in their subject matter by including explicit references to sex and using obscene language, leading to government censorship of books and magazines.

Censorship reached its height during World War I. The United States was swept up in two waves of hysteria. Anti-German feeling was provoked by the actions of Germany and its allies leading up to the war, including the sinking of the RMS Lusitania and the Zimmerman Telegram, an effort by the Germans to conclude an alliance with Mexico against the United States. This concern was compounded in 1917 by the Bolshevik revolution against the more moderate interim government of Russia; the leaders of the Bolsheviks, most notably Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and Joseph Stalin, withdrew from the war against Germany and called for communist revolutionaries to overthrow the capitalist, democratic governments in western Europe and North America.

Americans who vocally supported the communist cause or opposed the war often found themselves in jail. In Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled that people encouraging young men to dodge the draft could be imprisoned for doing so, arguing that recommending that people disobey the law was tantamount to “falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic” and thus presented a “clear and present danger” to public order.[26] Similarly, communists and other revolutionary anarchists and socialists during the Red Scare after the war were prosecuted under various state and federal laws for supporting the forceful or violent overthrow of government. This general approach to political speech remained in place for the next fifty years.

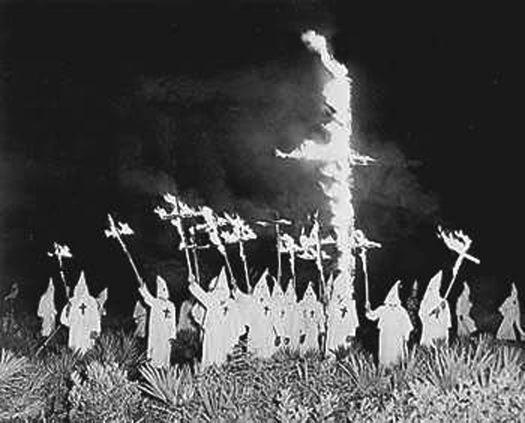

In the 1960s, however, the Supreme Court’s rulings on free expression became more liberal, in response to the Vietnam War and the growing antiwar movement. In a 1969 case involving the Ku Klux Klan, Brandenburg v. Ohio, the Supreme Court found that only speech or writing that constituted a direct call or plan to imminent lawless action, an illegal act in the immediate future, could be suppressed; the mere advocacy of a hypothetical revolution was not enough.[27] The Supreme Court also found that various forms of symbolic speech—wearing clothing like an armband that carried a political symbol or raising a fist in the air, for example—were subject to the same protections as written and spoken communication. More recently, symbolic speech related to the U.S. flag has engendered intense debate. Whether one should kneel during the national anthem, or ought to be able to burn the U.S. flag, are key questions.

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn more about freedom of the press.

MILESTONE

Burning the U.S. Flag

Perhaps no act of symbolic speech has been as controversial in U.S. history as the burning of the flag (Figure 3.9). Citizens tend to revere the flag as a unifying symbol of the country in much the same way most people in Britain would treat the reigning queen (or king). States and the federal government have long had laws protecting the flag from being desecrated—defaced, damaged, or otherwise treated with disrespect. Perhaps in part because of these laws, people who have wanted to drive home a point in opposition to U.S. government policies have found desecrating the flag a useful way to gain public and press attention to their cause.

One such person was Gregory Lee Johnson, a member of various pro-communist and antiwar groups. In 1984, as part of a protest near the Republican National Convention in Dallas, Texas, Johnson set fire to a U.S. flag that another protestor had torn from a flagpole. He was arrested, charged with “desecration of a venerated object” (among other offenses), and eventually convicted of that offense. However, in 1989, the Supreme Court decided in Texas v. Johnson that burning the flag was a form of symbolic speech protected by the First Amendment and found the law, as applied to flag desecration, to be unconstitutional.[28]

This court decision was strongly criticized, and Congress responded by passing a federal law, the Flag Protection Act, intended to overrule it; the act, too, was struck down as unconstitutional in 1990.[29] Since then, Congress has tried and failed on several occasions to propose constitutional amendments allowing the states and federal government to re-criminalize flag desecration.

Should we amend the Constitution to allow Congress or the states to pass laws protecting the U.S. flag from desecration? Should we protect other national symbols as well, such as standing for the national anthem? Why or why not?

Freedom of the press is an important component of the right to free expression as well. In Near v. Minnesota, an early case regarding press freedoms, the Supreme Court ruled that the government generally could not engage in prior restraint; that is, states and the federal government could not in advance prohibit someone from publishing something without a very compelling reason.[30] This standard was reinforced in 1971 in the Pentagon Papers case, in which the Supreme Court found that the government could not prohibit the New York Times and Washington Post newspapers from publishing the Pentagon Papers.[31] These papers included materials from a secret history of the Vietnam War that had been compiled by the military. More specifically, the papers were compiled at the request of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and provided a study of U.S. political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967. Daniel Ellsberg famously released passages of the Papers to the press to show that the United States had secretly enlarged the scope of the war by bombing Cambodia and Laos among other deeds while lying to the American public about doing so.

Although people who leak secret information to the media can still be prosecuted and punished, this does not generally extend to reporters and news outlets that pass that information on to the public. The Edward Snowden case is another good case in point. Snowden himself, rather than those involved in promoting the information that he shared, is the object of criminal prosecution.

Furthermore, the courts have recognized that government officials and other public figures might try to silence press criticism and avoid unfavorable news coverage by threatening a lawsuit for defamation of character. In the 1964 New York Times v. Sullivan case, the Supreme Court decided that public figures needed to demonstrate not only that a negative press statement about them was untrue but also that the statement was published or made with either malicious intent or “reckless disregard” for the truth.[32] This ruling made it much harder for politicians to silence potential critics or to bankrupt their political opponents through the courts.

The right to freedom of expression is not absolute; several key restrictions limit our ability to speak or publish opinions under certain circumstances. We have seen that the Constitution protects most forms of offensive and unpopular expression, particularly political speech; however, incitement of a criminal act, “fighting words,” and genuine threats are not protected. So, for example, you can’t point at someone in front of an angry crowd and shout, “Let’s beat up that guy!” And the Supreme Court has allowed laws that ban threatening symbolic speech, such as burning a cross on the lawn of an African American family’s home (Figure 3.10).[33] Finally, as we’ve just seen, defamation of character—whether in written form (libel) or spoken form (slander)—is not protected by the First Amendment, so people who are subject to false accusations can sue to recover damages, although criminal prosecutions of libel and slander are uncommon.

Another key exception to the right to freedom of expression is obscenity, acts or statements that are extremely offensive under current societal standards. Defining obscenity has been something of a challenge for the courts; Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said of obscenity, having watched pornography in the Supreme Court building, “I know it when I see it.” Into the early twentieth century, written work was frequently banned as being obscene, including works by noted authors such as James Joyce and Henry Miller, although today it is rare for the courts to uphold obscenity charges for written material alone. In 1973, the Supreme Court established the Miller test for deciding whether something is obscene: “(a) whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest, (b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and (c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”[34] However, the application of this standard has at times been problematic. In particular, the concept of “contemporary community standards” raises the possibility that obscenity varies from place to place; many people in New York or San Francisco might not bat an eye at something people in Memphis or Salt Lake City would consider offensive. The one form of obscenity that has been banned almost without challenge is child pornography, although even in this area the courts have found exceptions.

The courts have allowed censorship of less-than-obscene content when it is broadcast over the airwaves, particularly when it is available for anyone to receive. In general, these restrictions on indecency—a quality of acts or statements that offend societal norms or may be harmful to minors—apply only to radio and television programming broadcast when children might be in the audience, although most cable and satellite channels follow similar standards for commercial reasons. An infamous case of televised indecency occurred during the halftime show of the 2004 Super Bowl, during a performance by singer Janet Jackson in which a part of her clothing was removed by fellow performer Justin Timberlake, revealing her right breast. The network responsible for the broadcast, CBS, was ultimately presented with a fine of $550,000 by the Federal Communications Commission, the government agency that regulates television broadcasting. However, CBS was not ultimately required to pay.

On the other hand, in 1997, the NBC network showed a broadcast of Schindler’s List, a film depicting events during the Holocaust in Nazi Germany, without any editing, so it included graphic nudity and depictions of violence. NBC was not fined or otherwise punished, suggesting there is no uniform standard for indecency. Similarly, in the 1990s Congress compelled television broadcasters to implement a television ratings system, enforced by a “V-Chip” in televisions and cable boxes, so parents could better control the television programming their children might watch. However, similar efforts to regulate indecent content on the Internet to protect children from pornography have largely been struck down as unconstitutional. This outcome suggests that technology has created new avenues for obscene material to be disseminated. The Children’s Internet Protection Act, however, requires K–12 schools and public libraries receiving Internet access using special E-rate discounts to filter or block access to obscene material and other material deemed harmful to minors, with certain exceptions.

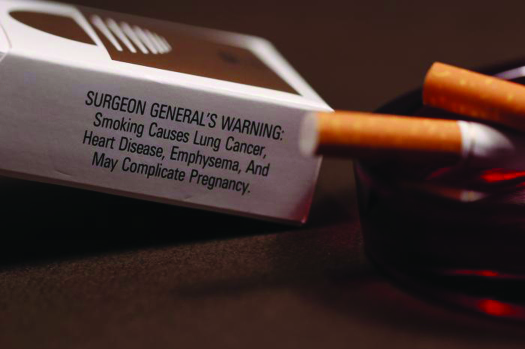

The courts have also allowed laws that forbid or compel certain forms of expression by businesses, such as laws that require the disclosure of nutritional information on food and beverage containers and warning labels on tobacco products (Figure 3.11). The federal government requires the prices advertised for airline tickets to include all taxes and fees. Many states regulate advertising by lawyers. And, in general, false or misleading statements made in connection with a commercial transaction can be illegal if they constitute fraud.

Furthermore, the courts have ruled that, although public school officials are government actors, the First Amendment freedom of expression rights of children attending public schools are somewhat limited. In particular, in Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) and Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the Supreme Court has upheld restrictions on speech that creates “substantial interference with school discipline or the rights of others”[35] or is “reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns.”[36] For example, the content of school-sponsored activities like school newspapers and speeches delivered by students can be controlled, either for the purposes of instructing students in proper adult behavior or to deter conflict between students.

Free expression includes the right to assemble peaceably and the right to petition government officials. This right even extends to members of groups whose views most people find abhorrent, such as American Nazis and the vehemently anti-LGBTQ Westboro Baptist Church, whose members have become known for their protests at the funerals of U.S. soldiers who have died fighting in the war on terror.[37] Free expression—although a broad right—is subject to certain constraints to balance it against the interests of public order. In particular, the nature, place, and timing of protests—but not their substantive content—are subject to reasonable limits. The courts have ruled that while people may peaceably assemble in a place that is a public forum, not all public property is a public forum. For example, the inside of a government office building or a college classroom—particularly while someone is teaching—is not generally considered a public forum.

Rallies and protests on land that has other dedicated uses, such as roads and highways, can be limited to groups that have secured a permit in advance, and those organizing large gatherings may be required to give sufficient notice so government authorities can ensure there is enough security available. However, any such regulation must be viewpoint-neutral; the government may not treat one group differently than another because of its opinions or beliefs. For example, the government can’t permit a rally by a group that favors a government policy but forbid opponents from staging a similar rally. Finally, there have been controversial situations in which government agencies have established free-speech zones for protesters during political conventions, presidential visits, and international meetings in areas that are arguably selected to minimize their public audience or to ensure that the subjects of the protests do not have to encounter the protesters.

The Second Amendment

There has been increased conflict over the Second Amendment in recent years due to school shootings and gun violence. As a result, gun rights have become a highly charged political issue. The text of the Second Amendment is among the shortest of those included in the Constitution:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

But the relative simplicity of its text has not kept it from controversy; arguably, the Second Amendment has become controversial in large part because of its text. Is this amendment merely a protection of the right of the states to organize and arm a “well regulated militia” for civil defense, or is it a protection of a “right of the people” as a whole to individually bear arms?

Before the Civil War, this would have been a nearly meaningless distinction. In most states at that time, White males of military age were considered part of the militia, liable to be called for service to put down rebellions or invasions, and the right “to keep and bear Arms” was considered a common-law right inherited from English law that predated the federal and state constitutions. The Constitution was not seen as a limitation on state power, and since the states expected all free men to keep arms as a matter of course, what gun control there was mostly revolved around ensuring enslaved people (and their abolitionist allies) didn’t have guns.

With the beginning of selective incorporation after the Civil War, debates over the Second Amendment were reinvigorated. In the meantime, as part of their Black codes designed to reintroduce most of the trappings of slavery, several southern states adopted laws that restricted the carrying and ownership of weapons by formerly enslaved people. Despite acknowledging a common-law individual right to keep and bear arms, in 1876 the Supreme Court declined, in United States v. Cruickshank, to intervene to ensure the states would respect it.[38]

In the following decades, states gradually began to introduce laws to regulate gun ownership. Federal gun control laws began to be introduced in the 1930s in response to organized crime, with stricter laws that regulated most commerce and trade in guns coming into force in the wake of the street protests of the 1960s. In the early 1980s, following an assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan, laws requiring background checks for prospective gun buyers were passed. During this period, the Supreme Court’s decisions regarding the meaning of the Second Amendment were ambiguous at best. In United States v. Miller, the Supreme Court upheld the 1934 National Firearms Act’s prohibition of sawed-off shotguns, largely on the basis that possession of such a gun was not related to the goal of promoting a “well regulated militia.”[39] This finding was generally interpreted as meaning that the Second Amendment protected the right of the states to organize a militia, rather than an individual right, and thus lower courts generally found most firearm regulations—including some city and state laws that virtually outlawed the private ownership of firearms—to be constitutional.

However, in 2008, in a narrow 5–4 decision on District of Columbia v. Heller, the Supreme Court found that at least some gun control laws did violate the Second Amendment and that this amendment does protect an individual’s right to keep and bear arms, at least in some circumstances—in particular, “for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home.”[40] Because the District of Columbia is not a state, this decision immediately applied the right only to the federal government and territorial governments. Two years later, in McDonald v. Chicago, the Supreme Court overturned the Cruickshank decision (5–4) and again found that the right to bear arms was a fundamental right incorporated against the states, meaning that state regulation of firearms might, in some circumstances, be unconstitutional. In 2015, however, the Supreme Court allowed several of San Francisco’s strict gun control laws to remain in place, suggesting that—as in the case of rights protected by the First Amendment—the courts will not treat gun rights as absolute (Figure 3.12).[41] Elsewhere in the political system, the gun issue remains similarly unsettled. However, in the wake of especially traumatic shootings at a Las Vegas outdoor concert and at a school in Parkland, Florida, there has been increased activism around gun control and community safety, especially among the young.[42]

The Third Amendment

The Third Amendment says in full:

“No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”

Most people consider this provision of the Constitution obsolete and unimportant. However, it is worthwhile to note its relevance in the context of the time: citizens remembered having their cities and towns occupied by British soldiers and mercenaries during the Revolutionary War, and they viewed the British laws that required the colonists to house soldiers particularly offensive, to the point that it had been among the grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence.

Today it seems unlikely the federal government would need to house military forces in civilian lodgings against the will of property owners or tenants; however, perhaps in the same way we consider the Second and Fourth amendments, we can think of the Third Amendment as reflecting a broader idea that our homes lie within a “zone of privacy” that government officials should not violate unless absolutely necessary.

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn more about search and seizure as it relates to the Fourth Amendment.

The Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment sits at the boundary between general individual freedoms and the rights of those suspected of crimes. We saw earlier that perhaps it reflects James Madison’s broader concern about establishing an expectation of privacy from government intrusion at home. Another way to think of the Fourth Amendment is that it protects us from overzealous efforts by law enforcement to root out crime by ensuring that police have good reason before they intrude on people’s lives with criminal investigations.

The text of the Fourth Amendment is as follows:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

The amendment places limits on both searches and seizures: Searches are efforts to locate documents and contraband. Seizures are the taking of these items by the government for use as evidence in a criminal prosecution (or, in the case of a person, the detention or taking of the person into custody).

In either case, the amendment indicates that government officials are required to apply for and receive a search warrant prior to a search or seizure; this warrant is a legal document, signed by a judge, allowing police to search and/or seize persons or property. Since the 1960s, however, the Supreme Court has issued a series of rulings limiting the warrant requirement in situations where a person can be said to lack a “reasonable expectation of privacy” outside the home. Police can also search and/or seize people or property without a warrant if the owner or renter consents to the search, if there is a reasonable expectation that evidence may be destroyed or tampered with before a warrant can be issued (i.e., exigent circumstances), or if the items in question are in plain view of government officials.

Furthermore, the courts have found that police do not generally need a warrant to search the passenger compartment of a car (Figure 3.13), or to search people entering the United States from another country.[43] When a warrant is needed, law enforcement officers do not need enough evidence to secure a conviction, but they must demonstrate to a judge that there is probable cause to believe a crime has been committed or evidence will be found. Probable cause is the legal standard for determining whether a search or seizure is constitutional or a crime has been committed; it is a lower threshold than the standard of proof at a criminal trial.

Critics have argued that this requirement is not very meaningful because law enforcement officers are almost always able to get a search warrant when they request one. On the other hand, since we wouldn’t expect the police to waste their time or a judge’s time trying to get search warrants that are unlikely to be granted, perhaps the high rate at which they get them should not be so surprising. The use of “no-knock” warrants based on the premise that a suspect would destroy drug evidence has recently been curtailed after the wrongful killing of Breonna Taylor by police serving such a warrant.[44], [45]

What happens if the police conduct an illegal search or seizure without a warrant and find evidence of a crime? In the 1961 Supreme Court case Mapp v. Ohio, the court decided that evidence obtained without a warrant that didn’t fall under one of the exceptions mentioned above could not be used as evidence in a state criminal trial, giving rise to the broad application of what is known as the exclusionary rule, which was first established in 1914 on a federal level in Weeks v. United States.[46] The exclusionary rule doesn’t just apply to evidence found or to items or people seized without a warrant (or falling under an exception noted above); it also applies to any evidence developed or discovered as a result of the illegal search or seizure.

For example, if police search your home without a warrant, find bank statements showing large cash deposits on a regular basis, and discover you are engaged in some other crime in which they were previously unaware (e.g., blackmail, drugs, or prostitution), they can neither use the bank statements as evidence of criminal activity, nor prosecute you for the crimes they discovered during the illegal search. This extension of the exclusionary rule is sometimes called the “fruit of the poisonous tree,” because just as the metaphorical tree (i.e., the original search or seizure) is poisoned, so is anything that grows out of it.[47]

However, like the requirement for a search warrant, the exclusionary rule does have exceptions. The courts have allowed evidence to be used that was obtained without the necessary legal procedures in circumstances where police executed warrants they believed were correctly granted but in fact were not (“good faith” exception), and when the evidence would have been found anyway had they followed the law (“inevitable discovery”).

The requirement of probable cause also applies to arrest warrants. A person cannot generally be detained by police or taken into custody without a warrant, although most states allow police to arrest someone suspected of a felony crime without a warrant so long as probable cause exists, and police can arrest people for minor crimes or misdemeanors they have witnessed themselves.

The Supreme Court’s 2012 and 2018 decisions in United States v. Jones and Carpenter v. United States extended the prohibition of illegal search and seizure to warrantless location tracking, either by installing a GPS device, as in the Jones case, or by accessing that information provided to cellular companies, as in Carpenter.

3.4 The Rights of Suspects

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the rights of those suspected or accused of criminal activity

- Explain how Supreme Court decisions transformed the rights of the accused

- Explain why the Eighth Amendment is controversial regarding capital punishment

In addition to protecting the personal freedoms of individuals, the Bill of Rights protects those suspected or accused of crimes from various forms of unfair or unjust treatment. The prominence of these protections in the Bill of Rights may seem surprising. Given the colonists’ experience of what they believed to be unjust rule by British authorities, however, and the use of the legal system to punish rebels and their sympathizers for political offenses, the impetus to ensure fair, just, and impartial treatment to everyone accused of a crime—no matter how unpopular—is perhaps more understandable. What is more, the revolutionaries, and the eventual framers of the Constitution, wanted to keep the best features of English law as well.

In addition to the protections outlined in the Fourth Amendment, which largely pertain to investigations conducted before someone has been charged with a crime, the next four amendments pertain to those suspected, accused, or convicted of crimes, as well as people engaged in other legal disputes. At every stage of the legal process, the Bill of Rights incorporates protections for these people.

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn more about due process law.

The Fifth Amendment

“No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

The first clause requires that serious crimes be prosecuted only after an indictment has been issued by a grand jury. However, several exceptions are permitted as a result of the evolving interpretation and understanding of this amendment by the courts, given the Constitution is a living document. First, the courts have generally found this requirement to apply only to felonies; less serious crimes can be tried without a grand jury proceeding. Second, this provision of the Bill of Rights does not apply to the states because it has not been incorporated; many states instead require a judge to hold a preliminary hearing to decide whether there is enough evidence to hold a full trial. Finally, members of the armed forces who are accused of crimes are not entitled to a grand jury proceeding.

The Fifth Amendment also protects individuals against double jeopardy, a process that subjects a suspect to prosecution twice for the same criminal act. No one who has been acquitted (found not guilty) of a crime can be prosecuted again for that crime. But the prohibition against double jeopardy has its own exceptions. The most notable is that it prohibits a second prosecution only at the same level of government (federal or state) as the first; the federal government can try you for violating federal law, even if a state or local court finds you not guilty of the same action. For example, in the early 1990s, several Los Angeles police officers accused of brutally beating motorist Rodney King during his arrest were acquitted of various charges in a state court, but some were later convicted in a federal court of violating King’s civil rights.

The double jeopardy rule does not prevent someone from recovering damages in a civil case—a legal dispute between individuals over a contract or compensation for an injury—that results from a criminal act, even if the person accused of that act is found not guilty. One famous case from the 1990s involved former football star and television personality O. J. Simpson. Simpson, although acquitted of the murders of his ex-wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ron Goldman in a criminal court, was later found to be responsible for their deaths in a subsequent civil case and as a result was forced to forfeit most of his wealth to pay damages to their families.

Perhaps the most famous provision of the Fifth Amendment is its protection against self-incrimination, or the right to remain silent. This provision is so well known that we have a phrase for it: “taking the Fifth.” People have the right not to give evidence in court or to law enforcement officers that might constitute an admission of guilt or responsibility for a crime. Moreover, in a criminal trial, if someone does not testify in their own defense, the prosecution cannot use that failure to testify as evidence of guilt or imply that an innocent person would testify. This provision became embedded in the public consciousness following the Supreme Court’s 1966 ruling in Miranda v. Arizona, whereby suspects were required to be informed of their most important rights, including the right against self-incrimination, before being interrogated in police custody.[48] However, contrary to some media depictions of the Miranda warning, law enforcement officials do not necessarily have to inform suspects of their rights before they are questioned in situations where they are free to leave.

Like the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause, the Fifth Amendment prohibits the federal government from depriving people of their “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Recall that due process is a guarantee that people will be treated fairly and impartially by government officials when the government seeks to fine or imprison them or take their personal property away from them. The courts have interpreted this provision to mean that government officials must establish consistent, fair procedures to decide when people’s freedoms are limited. In other words, citizens cannot be detained, their freedom limited, or their property taken arbitrarily or on a whim by police or other government officials. As a result, an entire body of procedural safeguards comes into play for the legal prosecution of crimes. However, the Patriot Act, passed into law after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, somewhat altered this notion.