The Judiciary

OpenStax and Lumen Learning; Tom Rozinski; and [Author removed at request of original publisher]

2.1 Introduction to the Courts

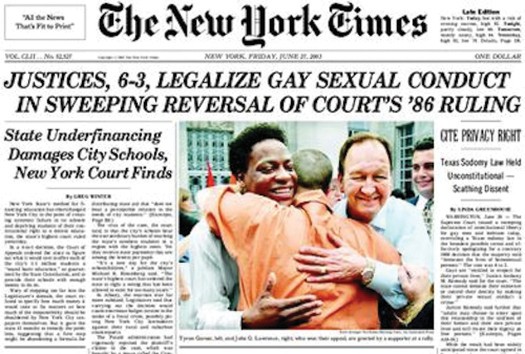

If democratic institutions struggle to balance individual freedoms and collective well-being, the judiciary is arguably the branch where the individual has the best chance to be heard. For those seeking protection on the basis of sexual orientation, for example, in recent years, the courts have expanded rights, such as the 2015 decision in which the Supreme Court ruled that same-sex couples have the right to marry in all fifty states (Figure 2.1).[1]

The U.S. courts pride themselves on two achievements: (1) as part of the system of checks and balances, they protect the sanctity of the U.S. Constitution from breaches by the other branches of government, and (2) they protect individual rights against societal and governmental oppression. At the federal level, nine Supreme Court judges are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate for lifetime appointments. This provides them the independence they need to carry out their duties. However, court power is confined to rulings on those cases the courts decide to hear.[2]

How do the courts make decisions, and how do they exercise their power to protect individual rights? How are the courts structured, and what distinguishes the Supreme Court from all others? This chapter answers these and other questions in delineating the power of the judiciary in the United States.

LINK TO LEARNING

-

Legal System Basics: Crash Course Government and Politics #18

*Watch this video to learn about the basics of the legal system.

2.2 Guardians of the Constitution and Individual Rights

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the evolving role of the courts since the ratification of the Constitution

- Explain why courts are uniquely situated to protect individual rights

- Recognize how the courts make public policy

Under the Article of Confederation, there was no National judiciary. The U.S. Constitution changed that, but its Article III, which addresses “the judicial power of the United States,” is the shortest and least detailed of the three articles that created the branches of government. It calls for the creation of “one supreme Court” and establishes the Court’s jurisdiction, or its authority to hear cases and make decisions about them, and the types of cases the Court may hear. It distinguishes which are matters of original jurisdiction and which are for appellate jurisdiction. Under original jurisdiction, a case is heard for the first time, whereas under appellate jurisdiction, a court hears a case on appeal from a lower court and may change the lower court’s decision. The Constitution also limits the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction to those rare cases of disputes between states, or between the United States and foreign ambassadors or ministers. So, for the most part, the Supreme Court is an appeals court, operating under appellate jurisdiction and hearing appeals from the lower courts. the rest of the development of the judicial system and creation of the lower courts were left in the hands of Congress.

To add further explanation to Article III, Alexander Hamilton wrote details about the federal judiciary in Federalist No. 78. In explaining the importance of an independent judiciary separated from the other branches of government, he said “interpretation” was a key role of the courts as they seek to protect people from unjust laws. But he also believed “the Judiciary Department” would “always be the least dangerous” because “with no influence over either the sword or the purse,” it had “neither force nor will, but merely judgment.” The courts would only make decisions, not take action. With no control over how those decisions would be implemented and no power to enforce their choices, they could exercise only judgment, and their power would begin and end there. Hamilton would no doubt be surprised by what the judiciary has become: a key component of the nation’s constitutional democracy, finding its place as the chief interpreter of the Constitution and the equal of the other two branches, though still checked and balanced by them.

The first session of the first U.S. Congress laid the framework for today’s federal judicial system, established in the Judiciary Act of 1789. Although legislative changes over the years have altered it, the basic structure of the judicial branch remains as it was set early on: At the lowest level are the district courts, where federal cases are tried, witnesses testify, and evidence and arguments are presented. A losing party who is unhappy with a district court decision may appeal to the circuit courts, or U.S. courts of appeals, where the decision of the lower court is reviewed. Still further, appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court is possible, but of the thousands of petitions for appeal, the Supreme Court will typically hear fewer than one hundred a year.[3]

LINK TO LEARNING

This public site maintained by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts provides detailed information from and about the judicial branch.

Humble Beginnings

Starting in New York in 1790, the early Supreme Court focused on establishing its rules and procedures and perhaps trying to carve its place as the new government’s third branch. However, given the difficulty of getting all the justices even to show up, and with no permanent home or building of its own for decades, finding its footing in the early days proved to be a monumental task. Even when the federal government moved to the nation’s capital in 1800, the Court had to share space with Congress in the Capitol building. This ultimately meant that “the high bench crept into an undignified committee room in the Capitol beneath the House Chamber.”[4]

It was not until the Court’s 146th year of operation that Congress, at the urging of Chief Justice—and former president—William Howard Taft, provided the designation and funding for the Supreme Court’s own building, “on a scale in keeping with the importance and dignity of the Court and the Judiciary as a coequal, independent branch of the federal government.”[5] It was a symbolic move that recognized the Court’s growing role as a significant part of the national government (Figure 2.2).

But it took years for the Court to get to that point, and it faced a number of setbacks on the way to such recognition. In their first case of significance, Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), the justices ruled that the federal courts could hear cases brought by a citizen of one state against a citizen of another state, and that Article III, Section 2, of the Constitution did not protect the states from facing such an interstate lawsuit.[6] However, their decision was almost immediately overturned by the Eleventh Amendment, passed by Congress in 1794 and ratified by the states in 1795. In protecting the states, the Eleventh Amendment put a prohibition on the courts by stating, “The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.” It was an early hint that Congress had the power to change the jurisdiction of the courts as it saw fit and stood ready to use it.

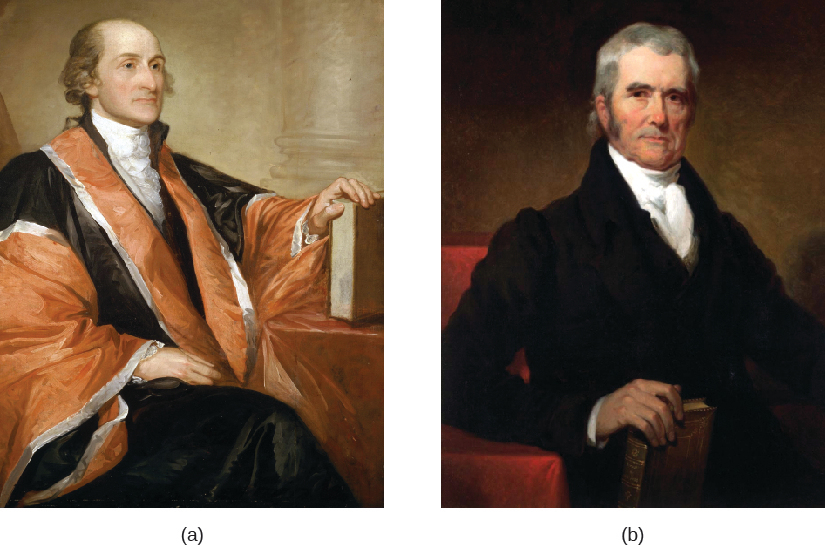

In an atmosphere of perceived weakness, the first chief justice, John Jay, an author of The Federalist Papers and appointed by President George Washington, resigned his post to become governor of New York and later declined President John Adams’s offer of a subsequent term.[7] In fact, the Court might have remained in a state of what Hamilton called its “natural feebleness” if not for the man who filled the vacancy Jay had refused—the fourth chief justice, John Marshall. Often credited with defining the modern court, clarifying its power, and strengthening its role, Marshall served in the chief’s position for thirty-four years. One landmark case during his tenure changed the course of the judicial branch’s history (Figure 2.3).[8]

In 1803, the Supreme Court declared for itself the power of judicial review, a power to which Hamilton had referred but that is not expressly mentioned in the Constitution. Judicial review is the power of the courts, as part of the system of checks and balances, to look at actions taken by the other branches of government and the states and determine whether they are constitutional. If the courts find an action to be unconstitutional, it becomes null and void. Judicial review was established in the Supreme Court case Marbury v. Madison, when, for the first time, the Court declared an act of Congress to be unconstitutional.[9] Wielding this power is a role Marshall defined as the “very essence of judicial duty,” and it continues today as one of the most significant aspects of judicial power. Judicial review lies at the core of the court’s ability to check the other branches of government—and the states.

Since Marbury, the power of judicial review has continually expanded, and the Court has not only ruled actions of Congress and the president to be unconstitutional, but it has also extended its power to include the review of state and local actions. The power of judicial review is not confined to the Supreme Court but is also exercised by the lower federal courts and even the state courts. Any legislative or executive action at the federal or state level inconsistent with the U.S. Constitution or a state constitution can be subject to judicial review.[10]

LINK TO LEARNING

-

Judicial Review: Crash Course Government and Politics #21

*Watch this video to learn about the basics of the legal system.

MILESTONE

Marbury v. Madison (1803)

The Supreme Court found itself in the middle of a dispute between the outgoing presidential administration of John Adams and that of incoming president (and opposition party member) Thomas Jefferson. It was an interesting circumstance at the time, particularly because Jefferson and the man who would decide the case—John Marshall—were themselves political rivals.

President Adams had appointed William Marbury to a position in Washington, DC, but his commission was not delivered before Adams left office. So Marbury petitioned the Supreme Court to use its power under the Judiciary Act of 1789 and issue a writ of mandamus to force the new president’s secretary of state, James Madison, to deliver the commission documents. It was a task Madison refused to do. A unanimous Court under the leadership of Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that although Marbury was entitled to the job, the Court did not have the power to issue the writ and order Madison to deliver the documents, because the provision in the Judiciary Act that had given the Court that power was unconstitutional.[11]

Perhaps Marshall feared a confrontation with the Jefferson administration and thought Madison would refuse his directive anyway. In any case, his ruling shows an interesting contrast in the early Court. On one hand, it humbly declined a power—issuing a writ of mandamus—given to it by Congress, but on the other, it laid the foundation for legitimizing a much more important one—judicial review. Marbury never got his commission, but the Court’s ruling in the case has become more significant for the precedent it established: As the first time the Court declared an act of Congress unconstitutional, it established the power of judicial review, a key power that enables the judicial branch to remain a powerful check on the other branches of government.

Consider the dual nature of John Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v. Madison: On one hand, it limits the power of the courts, yet on the other it also expanded their power. Explain the different aspects of the decision in terms of these contrasting results.

The Courts and Public Policy

Even with judicial review in place, the courts do not always stand ready just to throw out actions of the other branches of government. More broadly, as Marshall put it, “it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.”[12] The United States has a common law system in which law is largely developed through binding judicial decisions. With roots in medieval England, the system was inherited by the American colonies along with many other British traditions.[13] It stands in contrast to code law systems, which provide very detailed and comprehensive laws that do not leave room for much interpretation and judicial decision-making. With code law in place, as it is in many nations of the world, it is the job of judges to simply apply the law. But under common law, as in the United States, they interpret it. Often referred to as a system of judge-made law, common law provides the opportunity for the judicial branch to have stronger involvement in the process of law-making itself, largely through its ruling and interpretation on a case-by-case basis.

In their role as policymakers, Congress and the president tend to consider broad questions of public policy and their costs and benefits. But the courts consider specific cases with narrower questions, thus enabling them to focus more closely than other government institutions on the exact context of the individuals, groups, or issues affected by the decision. This means that while the legislature can make policy through statute, and the executive can form policy through regulations and administration, the judicial branch can also influence policy through its rulings and interpretations. As cases are brought to the courts, court decisions can help shape policy.

Consider health care, for example. In 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), a statute that brought significant changes to the nation’s healthcare system. With its goal of providing more widely attainable and affordable health insurance and health care, “Obamacare” was hailed by some but soundly denounced by others as bad policy. People who opposed the law and understood that a congressional repeal would not happen any time soon looked to the courts for help. They challenged the constitutionality of the law in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, hoping the Supreme Court would overturn it.[14] The practice of judicial review enabled the law’s critics to exercise this opportunity, even though their hopes were ultimately dashed when, by a narrow 5–4 margin, the Supreme Court upheld the health care law as a constitutional extension of Congress’s power to tax.

Since this 2012 decision, the ACA has continued to face challenges, the most notable of which have also been decided by court rulings. It faced a setback in 2014, for instance, when the Supreme Court ruled in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby that, for religious reasons, some for-profit corporations could be exempt from the requirement that employers provide insurance coverage of contraceptives for their female employees.[15] But the ACA also attained a victory in King v. Burwell, when the Court upheld the ability of the federal government to provide tax credits for people who bought their health insurance through an exchange created by the law.[16]

With each ACA case it has decided, the Supreme Court has served as the umpire, upholding the law and some of its provisions on one hand, but ruling some aspects of it unconstitutional on the other. Both supporters and opponents of the law have claimed victory and faced defeat. In each case, the Supreme Court has further defined and fine-tuned the law passed by Congress and the president, determining which parts stay and which parts go, thus having its say in the way the act has manifested itself, the way it operates, and the way it serves its public purpose.

In this same vein, the courts have become the key interpreters of the U.S. Constitution, continuously interpreting it and applying it to modern times and circumstances. For example, it was in 2015 that we learned a man’s threat to kill his ex-wife, written in rap lyrics and posted to her Facebook wall, was not a real threat and thus could not be prosecuted as a felony under federal law.[17] Certainly, when the Bill of Rights first declared that government could not abridge freedom of speech, its framers could never have envisioned Facebook—or any other modern technology for that matter.

But freedom of speech, just like many constitutional concepts, has come to mean different things to different generations, and it is the courts that have designed the lens through which we understand the Constitution in modern times. It is often said that the Constitution changes less by amendment and more by the way it is interpreted. Rather than collecting dust on a shelf, the nearly 230-year-old document has come with us into the modern age, and the accepted practice of judicial review has helped carry it along the way.

Courts as a Last Resort

While the U.S. Supreme Court and state supreme courts exert power over many when reviewing laws or declaring acts of other branches unconstitutional, they become particularly important when an individual or group comes before them believing there has been a wrong. A citizen or group that feels mistreated can approach a variety of institutional venues in the U.S. system for assistance in changing policy or seeking support. Organizing protests, garnering special interest group support, and changing laws through the legislative and executive branches are all possible, but an individual is most likely to find the courts especially well-suited to analyzing the particulars of a case.

The adversarial judicial system comes from the common law tradition: In a court case, it is one party versus the other, and it is up to an impartial person or group, such as the judge or jury, to determine which party prevails. The federal court system is most often called upon when a case touches on constitutional rights. For example, when Samantha Elauf, a Muslim woman, was denied a job working for the clothing retailer Abercrombie & Fitch because a headscarf she wears as religious practice violated the company’s dress code, the Supreme Court ruled that her First Amendment rights had been violated, making it possible for her to sue the store for monetary damages.

Elauf had applied for an Abercrombie sales job in Oklahoma in 2008. Her interviewer recommended her based on her qualifications, but she was never given the job because the clothing retailer wanted to avoid having to accommodate her religious practice of wearing a headscarf, or hijab. In so doing, the Court ruled, Abercrombie violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits employers from discriminating on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, and requires them to accommodate religious practices.[18]

Rulings like this have become particularly important for members of religious minority groups, including Muslims, Sikhs, and Jews, who now feel more protected from employment discrimination based on their religious attire, head coverings, or beards.[19] Such decisions illustrate how the expansion of individual rights and liberties for particular persons or groups over the years has come about largely as a result of court rulings made for individuals on a case-by-case basis.

Although the United States prides itself on the Declaration of Independence’s statement that “all men are created equal,” and “equal protection of the laws” is a written constitutional principle of the Fourteenth Amendment, the reality is less than perfect. But it is evolving. Changing times and technology have and will continue to alter the way fundamental constitutional rights are defined and applied, and the courts have proven themselves to be crucial in that definition and application.

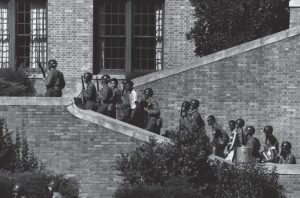

Societal traditions, public opinion, and politics have often stood in the way of the full expansion of rights and liberties to different groups, and not everyone has agreed that these rights should be expanded as they have been by the courts. Schools were long segregated by race until the Court ordered desegregation in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), and even then, many stood in opposition and tried to block students at the entrances to all-White schools.[20] Factions have formed on opposite sides of the abortion and handgun debates, because many do not agree that women should have abortion rights or that individuals should have the right to a handgun. People disagree about whether members of the LGBTQ community should be allowed to marry or whether arrested persons should be read their rights, guaranteed an attorney, and/or have their cell phones protected from police search.

But the Supreme Court has ruled in favor of all these issues and others. Even without unanimous agreement among citizens, Supreme Court decisions have made all these possibilities a reality, a particularly important one for the individuals who become the beneficiaries (Table 2.1). The judicial branch has often made decisions the other branches were either unwilling or unable to make, and Hamilton was right in Federalist No. 78 when he said that without the courts exercising their duty to defend the Constitution, “all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing.”

| Examples of Supreme Court Cases Involving Individuals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Case Name | Year | Court’s Decision |

| Brown v. Board of Education | 1954 | Public schools must be desegregated. |

| Gideon v. Wainwright | 1963 | Poor criminal defendants must be provided an attorney. |

| Miranda v. Arizona | 1966 | Criminal suspects must be read their rights. |

| Roe v. Wade | 1973 | Women have a constitutional right to abortion. |

| McDonald v. Chicago | 2010 | An individual has the right to a handgun in his or her home. |

| Riley v. California | 2014 | Police may not search a cell phone without a warrant. |

| Obergefell v. Hodges | 2015 | Same-sex couples have the right to marry in all states. |

The courts seldom if ever grant rights to a person instantly and upon request. In a number of cases, they have expressed reluctance to expand rights without limit, and they still balance that expansion with the government’s need to govern, provide for the common good, and serve a broader societal purpose. For example, the Supreme Court has upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty, ruling that the Eighth Amendment does not prevent a person from being put to death for committing a capital crime and that the government may consider “retribution and the possibility of deterrence” when it seeks capital punishment for a crime that so warrants it.[21] In other words, there is a greater good—more safety and security—that may be more important than sparing the life of an individual who has committed a heinous crime.

Yet the Court has also put limits on the ability to impose the death penalty, ruling, for example, that the government may not execute a person with cognitive disabilities, a person who was under eighteen at the time of the crime, or a child rapist who did not kill his victim.[22] So the job of the courts on any given issue is never quite done, as justices continuously keep their eye on government laws, actions, and policy changes as cases are brought to them and then decide whether those laws, actions, and policies can stand or must go. Even with an issue such as the death penalty, about which the Court has made several rulings, there is always the possibility that further judicial interpretation of what does (or does not) violate the Constitution will be needed.

This happened, for example, as recently as 2015 in a case involving the use of lethal injection as capital punishment in the state of Oklahoma, where death-row inmates are put to death through the use of three drugs—a sedative to bring about unconsciousness (midazolam), followed by two others that cause paralysis and stop the heart. A group of these inmates challenged the use of midazolam as unconstitutional. They argued that since it could not reliably cause unconsciousness, its use constituted an Eighth Amendment violation against cruel and unusual punishment and should be stopped by the courts. The Supreme Court rejected the inmates’ claims, ruling that Oklahoma could continue to use midazolam as part of its three-drug protocol.[23] But with four of the nine justices dissenting from that decision, a sharply divided Court leaves open a greater possibility of more death-penalty cases to come. The 2015–2016 session alone includes four such cases, challenging death-sentencing procedures in such states as Florida, Georgia, and Kansas.[24] In another recent case, Bucklew v. Precythe (2019), the court again rejected an Eighth Amendment claim of the death penalty as torture.[25] Yet, while case outcomes would suggest that it is easier, not harder, to carry out the death penalty, the number of executions across the U.S. has plummeted in recent years.[26]

Therefore, we should not underestimate the power and significance of the judicial branch in the United States. Today, the courts have become a relevant player, gaining enough clout and trust over the years to take their place as a separate yet coequal branch.

2.3 The Dual Court System

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the dual court system and its three tiers

- Explain how you are protected and governed by different U.S. court systems

- Compare the positive and negative aspects of a dual court system

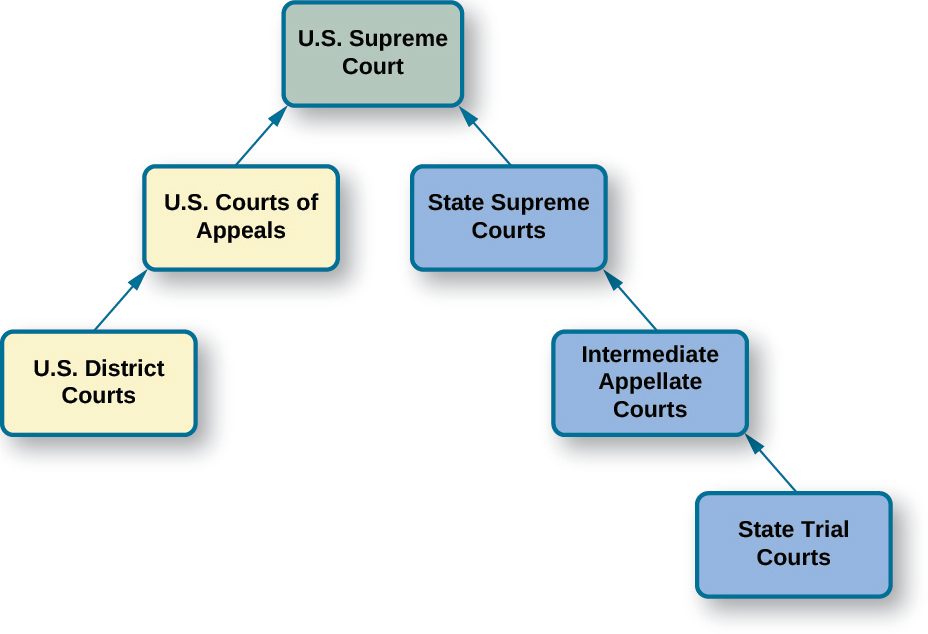

Before the writing of the U.S. Constitution and the establishment of the permanent national judiciary under Article III, the states had courts. Each of the thirteen colonies had also had its own courts, based on the British common law model. The judiciary today continues as a dual court system, with courts at both the national and state levels. Both levels have three basic tiers consisting of appellate courts, and finally courts of last resort, typically called supreme courts, at the top (Figure 2.4).

LINK TO LEARNING

-

Structure of the Court System: Crash Course Government and Politics #19

*Watch this video to learn about the structure of the court system in the Unites States.

To add to the complexity, the state and federal court systems sometimes intersect and overlap each other, and no two states are exactly alike when it comes to the organization of their courts. Since a state’s court system is created by the state itself, each one differs in structure, the number of courts, and even name and jurisdiction. Thus, the organization of state courts closely resembles but does not perfectly mirror the more clear-cut system found at the federal level.[27] Still, we can summarize the overall three-tiered structure of the dual court model and consider the relationship that the national and state sides share with the U.S. Supreme Court, as illustrated in Figure 2.4.

Cases heard by the U.S. Supreme Court come from two primary pathways: (1) the circuit courts, or U.S. courts of appeals (after the cases have originated in the federal district courts), and (2) state supreme courts (when there is a substantive federal question in the case). In a later section of the chapter, we discuss the lower courts and the movement of cases through the dual court system to the U.S. Supreme Court. But first, to better understand how the dual court system operates, we consider the types of cases state and local courts handle and the types for which the federal system is better designed.

Courts and Federalism

Courts hear two different types of disputes: criminal and civil. Under criminal law, governments establish rules and punishments; laws define conduct that is prohibited because it can harm others and impose punishment for committing such an act. Crimes are usually labeled felonies or misdemeanors based on their nature and seriousness; felonies are the more serious crimes. When someone commits a criminal act, the government (state or national, depending on which law has been broken) charges that person with a crime, and the case brought to court contains the name of the charging government, as in Miranda v. Arizona discussed below.[28] On the other hand, civil law cases involve two or more private (non-government) parties, at least one of whom alleges harm or injury committed by the other. In both criminal and civil matters, the courts decide the remedy and resolution of the case, and in all cases, the U.S. Supreme Court is the final court of appeal.

LINK TO LEARNING

This site provides an interesting challenge: Look at the different cases presented and decide whether each would be heard in the state or federal courts. You can check your results at the end.

Although the Supreme Court tends to draw the most public attention, it typically hears fewer than one hundred cases every year. In fact, the entire federal side—both trial and appellate—handles proportionately very few cases, with about 90 percent of all cases in the U.S. court system being heard at the state level.[29] The several hundred thousand cases handled every year on the federal side pale in comparison to the several million handled by the states.

State courts really are the core of the U.S. judicial system, and they are responsible for a huge area of law. Most crimes and criminal activity, such as robbery, rape, and murder, are violations of state laws, and cases are thus heard by state courts. State courts also handle civil matters; personal injury, malpractice, divorce, family, juvenile, probate, and contract disputes and real estate cases, to name just a few, are usually state-level cases.

The federal courts, on the other hand, will hear any case that involves a foreign government, patent or copyright infringement, Native American rights, maritime law, bankruptcy, or a controversy between two or more states. Cases arising from activities across state lines (interstate commerce) are also subject to federal court jurisdiction, as are cases in which the United States is a party. A dispute between two parties not from the same state or nation and in which damages of at least $75,000 are claimed is handled at the federal level. Such a case is known as a diversity of citizenship case.[30]

However, some cases cut across the dual court system and may end up being heard in both state and federal courts. Any case has the potential to make it to the federal courts if it invokes the U.S. Constitution or federal law. It could be a criminal violation of federal law, such as assault with a gun, the illegal sale of drugs, or bank robbery. Or it could be a civil violation of federal law, such as employment discrimination or securities fraud. Also, any perceived violation of a liberty protected by the Bill of Rights, such as freedom of speech or the protection against cruel and unusual punishment, can be argued before the federal courts. A summary of the basic jurisdictions of the state and federal sides is provided in Table 2.2.

| Jurisdiction of the Courts: State vs. Federal | |

|---|---|

| State Courts | Federal Courts |

| Hear most day-to-day cases, covering 90 percent of all cases | Hear cases that involve a “federal question,” involving the Constitution, federal laws or treaties, or a “federal party” in which the U.S. government is a party to the case |

| Hear both civil and criminal matters | Hear both civil and criminal matters, although many criminal cases involving federal law are tried in state courts |

| Help the states retain their own sovereignty in judicial matters over their state laws, distinct from the national government | Hear cases that involve “interstate” matters, “diversity of citizenship” involving parties of two different states, or between a U.S. citizen and a citizen of another nation (and with a damage claim of at least $75,000) |

While we may certainly distinguish between the two sides of a jurisdiction, looking on a case-by-case basis will sometimes complicate the seemingly clear-cut division between the state and federal sides. It is always possible that issues of federal law may start in the state courts before they make their way over to the federal side. And any case that starts out at the state and/or local level on state matters can make it into the federal system on appeal—but only on points that involve a federal law or question, and usually after all avenues of appeal in the state courts have been exhausted.[31]

Consider the case Miranda v. Arizona.[32] Ernesto Miranda, arrested for kidnapping and rape, which are violations of state law, was easily convicted and sentenced to prison after a key piece of evidence—his own signed confession—was presented at trial in the Arizona court. On appeal first to the Arizona Supreme Court and then to the U.S. Supreme Court to exclude the confession on the grounds that its admission was a violation of his constitutional rights, Miranda won the case. By a slim 5–4 margin, the justices ruled that the confession had to be excluded from evidence because in obtaining it, the police had violated Miranda’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination and his Sixth Amendment right to an attorney. In the opinion of the Court, because of the coercive nature of police interrogation, no confession can be admissible unless a suspect is made aware of his rights and then in turn waives those rights. For this reason, Miranda’s original conviction was overturned.

Yet the Supreme Court considered only the violation of Miranda’s constitutional rights, but not whether he was guilty of the crimes with which he was charged. So there were still crimes committed for which Miranda had to face charges. He was therefore retried in state court in 1967, the second time without the confession as evidence, found guilty again based on witness testimony and other evidence, and sent to prison.

Miranda’s story is a good example of the tandem operation of the state and federal court systems. His guilt or innocence of the crimes was a matter for the state courts, whereas the constitutional questions raised by his trial were a matter for the federal courts. Although he won his case before the Supreme Court, which established a significant precedent that criminal suspects must be read their so-called Miranda rights before police questioning, the victory did not do much for Miranda himself. After serving prison time, he was stabbed to death in a bar fight in 1976 while out on parole, and due to a lack of evidence, no one was ever convicted in his death.

The Implications of a Dual Court System

From an individual’s perspective, the dual court system has both benefits and drawbacks. On the plus side, each person has more than just one court system ready to protect that individual’s rights. The dual court system provides alternate venues in which to appeal for assistance, as Ernesto Miranda’s case illustrates. The U.S. Supreme Court found for Miranda an extension of his Fifth Amendment protections—a constitutional right to remain silent when faced with police questioning. It was a right he could not get solely from the state courts in Arizona, but one those courts had to honor nonetheless.

The fact that a minority voice like Miranda’s can be heard in court, and that grievances can be resolved in a minority voice’s favor if warranted, says much about the role of the judiciary in a democratic republic. In Miranda’s case, a resolution came from the federal courts, but it can also come from the state side. In fact, the many differences among the state courts themselves may enhance an individual’s potential to be heard.

State courts vary in the degree to which they take on certain types of cases or issues, give access to particular groups, or promote certain interests. If a particular issue or topic is not taken up in one place, it may be handled in another, giving rise to many different opportunities for an interest to be heard somewhere across the nation. In their research, Paul Brace and Melinda Hall found that state courts are important instruments of democracy because they provide different alternatives and varying arenas for political access. They wrote, “Regarding courts, one size does not fit all, and the republic has survived in part because federalism allows these critical variations.”[33]

But the existence of the dual court system and variations across the states and nation also mean that there are different courts in which a person could face charges for a crime or for a violation of another person’s rights. Except for the fact that the U.S. Constitution binds judges and justices in all the courts, it is state law that governs the authority of state courts, so judicial rulings about what is legal or illegal may differ from state to state. These differences are particularly pronounced when the laws across the states and the nation are not the same, as we see with marijuana laws today.

FINDING A MIDDLE GROUND

Marijuana Laws and the Courts

There are so many differences in marijuana laws between states, and between the states and the national government, that uniform application of treatment in courts across the nation is nearly impossible (Figure 2.5). What is legal in one state may be illegal in another, and state laws do not cross state geographic boundary lines—but people do. What’s more, a person residing in any of the fifty states is still subject to federal law.

For example, a person over the age of twenty-one may legally buy marijuana for recreational use in sixteen states and for medicinal purpose in more than 80 percent of the country, but could face charges—and time in court—for possession in a neighboring state where marijuana use is not legal. Under federal law, too, marijuana is still regulated as a Schedule 1 (most dangerous) drug, and federal authorities often find themselves pitted against states that have legalized it. Such differences can lead, somewhat ironically, to arrests and federal criminal charges for people who have marijuana in states where it is legal, or to federal raids on growers and dispensaries that would otherwise be operating legally under their state’s law.

Differences among the states have also prompted a number of lawsuits against states with legalized marijuana, as people opposed to those state laws seek relief from (none other than) the courts. They want the courts to resolve the issue, which has left in its wake contradictions and conflicts between states that have legalized marijuana and those that have not, as well as conflicts between states and the national government. These lawsuits include at least one filed by the states of Nebraska and Oklahoma against Colorado. Citing concerns over cross-border trafficking, difficulties with law enforcement, and violations of the Constitution’s supremacy clause, Nebraska and Oklahoma have petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene and rule on the legality of Colorado’s marijuana law, hoping to get it overturned.[34] The Supreme Court has yet to take up the case.

How do you think differences among the states and differences between federal and state law regarding marijuana use can affect the way a person is treated in court? What, if anything, should be done to rectify the disparities in application of the law across the nation?

Where you are physically located can affect not only what is allowable and what is not, but also how cases are judged. For decades, political scientists have confirmed that political culture affects the operation of government institutions, and when we add to that the differing political interests and cultures at work within each state, we end up with court systems that vary greatly in their judicial and decision-making processes.[35] Each state court system operates with its own individual set of biases. People with varying interests, ideologies, behaviors, and attitudes run the disparate legal systems, so the results they produce are not always the same. Moreover, the selection method for judges at the state and local level varies. In some states, judges are elected rather than appointed, which can affect their rulings.

Just as the laws vary across the states, so do judicial rulings and interpretations, and the judges who make them. That means there may not be uniform application of the law—even of the same law—nationwide. We are somewhat bound by geography and do not always have the luxury of picking and choosing the venue for our particular case. So, while having such a decentralized and varied set of judicial operations affects the kinds of cases that make it to the courts and gives citizens alternate locations to get their case heard, it may also lead to disparities in the way they are treated once they get there.

2.4 The Federal Court System

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the differences between the U.S. district courts, circuit courts, and the Supreme Court

- Explain the significance of precedent in the courts’ operations

- Describe how judges are selected for their positions

Congress has made numerous changes to the federal judicial system throughout the years, but the three-tiered structure of the system is quite clear-cut today. Federal cases typically begin at the lowest federal level, the district (or trial) court. Losing parties may appeal their case to the higher courts—first to the circuit courts, or U.S. courts of appeals, and then, if chosen by the justices, to the U.S. Supreme Court. Decisions of the higher courts are binding on the lower courts. The precedent set by each ruling, particularly by the Supreme Court’s decisions, both builds on principles and guidelines set by earlier cases and frames the ongoing operation of the courts, steering the direction of the entire system. Reliance on precedent has enabled the federal courts to operate with logic and consistency that has helped validate their role as the key interpreters of the Constitution and the law—a legitimacy particularly vital in the United States, where citizens do not elect federal judges and justices but are still subject to their rulings.

The Three Tiers of Federal Courts

There are ninety-four U.S. district courts in the fifty states and U.S. territories, of which eighty-nine are in the states (at least one in each state). The others are in Washington, DC; Puerto Rico; Guam; the U.S. Virgin Islands; and the Northern Mariana Islands. These are the trial courts of the national system, in which federal cases are tried, witness testimony is heard, and evidence is presented. No district court crosses state lines, and a single judge oversees each one. Some cases are heard by a jury, and some are not.

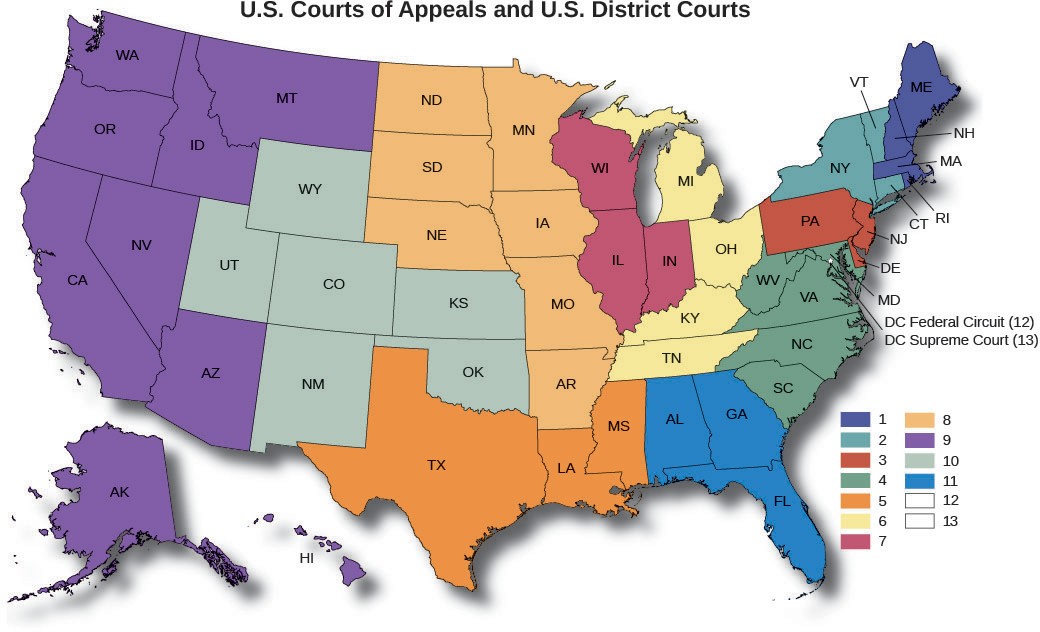

There are thirteen U.S. courts of appeals, or circuit courts, eleven across the nation and two in Washington, DC (the DC circuit and the federal circuit courts). Each court is overseen by a rotating panel of three judges who do not hold trials but instead review the rulings of the trial (district) courts within their geographic circuit. As authorized by Congress, there are currently 179 judges. The circuit courts are often referred to as the intermediate appellate courts of the federal system, since their rulings can be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Moreover, different circuits can hold legal and cultural views, which can lead to differing outcomes on similar legal questions. In such scenarios, clarification from the U.S. Supreme Court might be needed.

Today’s federal court system was not an overnight creation; it has been changing and transitioning for more than two hundred years through various acts of Congress. Since district courts are not called for in Article III of the Constitution, Congress established them and narrowly defined their jurisdiction, at first limiting them to handling only cases that arose within the district. Beginning in 1789 when there were just thirteen, the district courts became the basic organizational units of the federal judicial system. Gradually over the next hundred years, Congress expanded their jurisdiction, in particular over federal questions, which enables them to review constitutional issues and matters of federal law. In the Judicial Code of 1911, Congress made the U.S. district courts the sole general-jurisdiction trial courts of the federal judiciary, a role they had previously shared with the circuit courts.[36]

The circuit courts started out as the trial courts for most federal criminal cases and for some civil suits, including those initiated by the United States and those involving citizens of different states. But early on, they did not have their own judges; the local district judge and two Supreme Court justices formed each circuit court panel. (That is how the name “circuit” arose—judges in the early circuit courts traveled from town to town to hear cases, following prescribed paths or circuits to arrive at destinations where they were needed.[37]) Circuit courts also exercised appellate jurisdiction (meaning they receive appeals on federal district court cases) over most civil suits that originated in the district courts; however, that role ended in 1891, and their appellate jurisdiction was turned over to the newly created circuit courts, or U.S. courts of appeals. The original circuit courts—the ones that did not have “of appeals” added to their name—were abolished in 1911, fully replaced by these new circuit courts of appeals.[38]

While we often focus primarily on the district and circuit courts of the federal system, other federal trial courts exist that have more specialized jurisdictions, such as the Court of International Trade, Court of Federal Claims, and U.S. Tax Court. Specialized federal appeals courts include the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces and the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims. Cases from any of these courts may also be appealed to the Supreme Court, although that result is very rare.

On the U.S. Supreme Court, there are nine justices—one chief justice and eight associate justices. Circuit courts each contain three justices, whereas federal district courts have just one judge each. As the national court of last resort for all other courts in the system, the Supreme Court plays a vital role in setting the standards of interpretation that the lower courts follow. The Supreme Court’s decisions are binding across the nation and establish the precedent by which future cases are resolved in all the system’s tiers.

The U.S. court system operates on the principle of stare decisis (Latin for stand by things decided), which means that today’s decisions are based largely on rulings from the past, and tomorrow’s rulings rely on what is decided today. Stare decisis is especially important in the U.S. common law system, in which the consistency of precedent ensures greater certainty and stability in law and constitutional interpretation, and it also contributes to the solidity and legitimacy of the court system itself. As former Supreme Court justice Benjamin Cardozo summarized it years ago, “Adherence to precedent must then be the rule rather than the exception if litigants are to have faith in the even-handed administration of justice in the courts.”[39]

LINK TO LEARNING

With a focus on federal courts and the public, this website reveals the different ways the federal courts affect the lives of U.S. citizens and how those citizens interact with the courts.

When the legal facts of one case are the same as the legal facts of another, stare decisis dictates that they should be decided the same way, and judges are reluctant to disregard precedent without justification. However, that does not mean there is no flexibility or that new precedents or rulings can never be created. They often are. Certainly, court interpretations can change as times and circumstances change—and as the courts themselves change when new judges are selected and take their place on the bench. For example, the membership of the Supreme Court had changed entirely between Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which brought the doctrine of “separate but equal” and Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which required integration.[40]

The Selection of Judges

Judges fulfill a vital role in the U.S. judicial system and are carefully selected. At the federal level, the president nominates a candidate to a judgeship or justice position, and the nominee must be confirmed by a majority vote in the U.S. Senate, a function of the Senate’s “advice and consent” role. All judges and justices in the national courts serve lifetime terms of office.

The president sometimes chooses nominees from a list of candidates maintained by the American Bar Association, a national professional organization of lawyers.[41] The president’s nominee is then discussed (and sometimes hotly debated) in the Senate Judiciary Committee. After a committee vote, the candidate must be confirmed by a majority vote of the full Senate. He or she is then sworn in, taking an oath of office to uphold the Constitution and the laws of the United States.

When a vacancy occurs in a lower federal court, by custom, the president consults with that state’s U.S. senators before making a nomination. Through such senatorial courtesy, senators exert considerable influence on the selection of judges in their state, especially those senators who share a party affiliation with the president. In many cases, a senator can block a proposed nominee just by voicing his or her opposition. Thus, a presidential nominee typically does not get far without the support of the senators from the nominee’s home state.

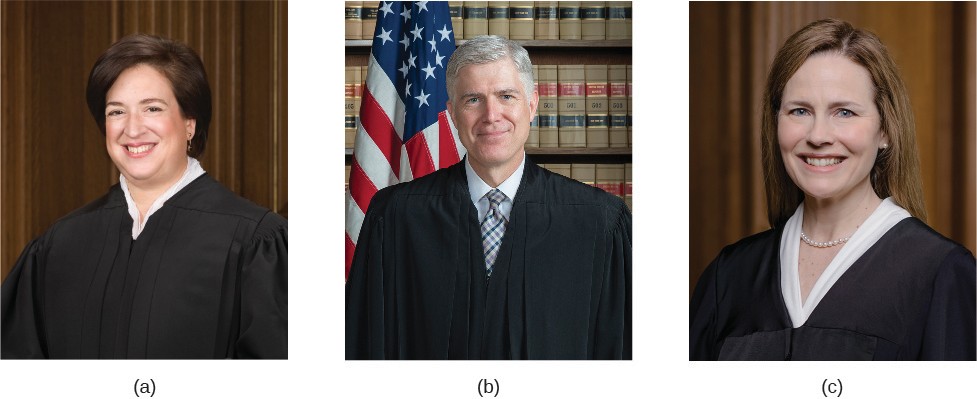

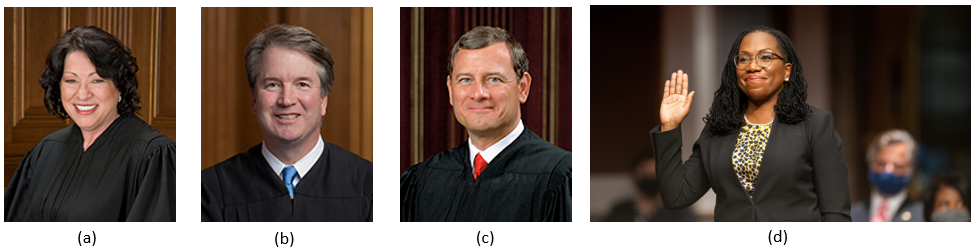

Most presidential appointments to the federal judiciary go unnoticed by the public, but when a president has the rarer opportunity to make a Supreme Court appointment, it draws more attention. That is particularly true now, when many people get their news primarily from the Internet and social media. It was not surprising to see not only television news coverage but also blogs and tweets about President Obama’s nominees to the high court, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, or President Trump’s nominees Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett.

Presidential nominees for the courts typically reflect the chief executive’s own ideological position. With a confirmed nominee serving a lifetime appointment, a president’s ideological legacy has the potential to live on long after the end of the term.[42] President Obama surely considered the ideological leanings of his two Supreme Court appointees, and both Sotomayor and Kagan have consistently ruled in a more liberal ideological direction. The timing of the two nominations also dovetailed nicely with the Democratic Party’s gaining control of the Senate in the 111th Congress of 2009–2011, which helped guarantee their confirmations. Similarly, Republican Donald Trump was able to confirm his three nominations (Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett) while Republicans controlled the Senate.

But some nominees turn out to be surprises or end up ruling in ways that the president who nominated them did not anticipate. Democratic-appointed judges sometimes side with conservatives, just as Republican-appointed judges sometimes side with liberals. Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower reportedly called his nomination of Earl Warren as chief justice—in an era that saw substantial broadening of civil and criminal rights—“the biggest damn fool mistake” he had ever made. Sandra Day O’Connor, nominated by Republican President Ronald Reagan, often became a champion for women’s rights. David Souter, nominated by Republican George H. W. Bush, more often than not sided with the Court’s liberal wing. Anthony Kennedy, a Reagan appointee who retired in the summer of 2018, was notorious as the Court’s swing vote, sometimes siding with the more conservative justices but sometimes not. Current chief justice John Roberts, though most typically an ardent member of the Court’s more conservative wing, has twice voted to uphold provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

One of the reasons the framers of the U.S. Constitution included the provision that federal judges would be appointed for life was to provide the judicial branch with enough independence such that it could not easily be influenced by the political winds of the time. The nomination of Brett Kavanaugh tested that notion, as the process became intensely partisan within the Senate and with the nominee himself. (Kavanaugh’s previous nomination to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit by President George W. Bush in 2003 also stalled for three years over charges of partisanship.) Sharp divisions emerged early in the confirmation process and an upset Kavanaugh called out several Democratic senators in his impassioned testimony in front of the Judiciary Committee. The high partisan drama of the Kavanaugh confirmation compelled Chief Justice Roberts to express concerns about the process and decry the threat of partisanship and conflict of interest on the Court.

Once a justice has started his or her lifetime tenure on the Court and years begin to pass, many people simply forget which president nominated him or her. For better or worse, sometimes it is only a controversial nominee who leaves a president’s legacy behind. For example, the Reagan presidency is often remembered for two controversial nominees to the Supreme Court—Robert Bork and Douglas Ginsburg, the former accused of taking an overly conservative and “extremist view of the Constitution”[43] and the latter of having used marijuana while a student and then a professor at Harvard University. President George W. Bush’s nomination of Harriet Miers was withdrawn in the face of criticism from both sides of the political spectrum, questioning her ideological leanings and especially her qualifications, suggesting she was not ready for the job.[44] After Miers’ withdrawal, the Senate went on to confirm Bush’s subsequent nomination of Samuel Alito, who remains on the Court today.

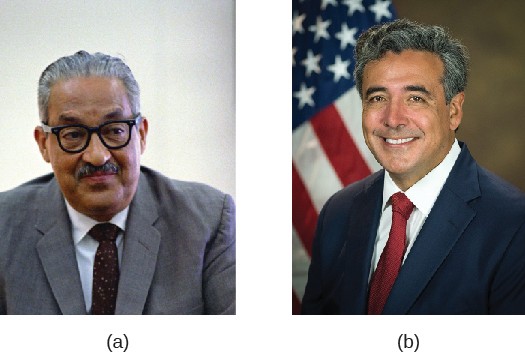

Presidential legacy and controversial nominations notwithstanding, there is one certainty about the overall look of the federal court system: What was once a predominantly White, male, Protestant institution is today much more diverse. As a look at the table below reveals, the membership of the Supreme Court has changed with the passing years.

| Supreme Court Justice Firsts | |

|---|---|

| First Catholic | Roger B. Taney (nominated in 1836) |

| First Jew | Louis J. Brandeis (1916) |

| First (and only) former U.S. President | William Howard Taft (1921) |

| First African American | Thurgood Marshall (1967) |

| First Woman | Sandra Day O’Connor (1981) |

| First Hispanic American | Sonia Sotomayor (2009) |

The lower courts are also more diverse today. In the past few decades, the U.S. judiciary has expanded to include more women and minorities at both the federal and state levels.[45] However, the number of women and people of color on the courts still lags behind the overall number of White men. As of 2021, the federal judiciary consists of 67 percent men, 33 percent women. In terms of race and ethnicity, 74 percent of federal judges are White, 12 percent African American, 8 percent Latinx, and 4 percent Asian American.[46]

2.5 The Supreme Court

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Analyze the structure and important features of the Supreme Court

- Explain how the Supreme Court selects cases to hear

- Discuss the Supreme Court’s processes and procedures.

The Supreme Court of the United States, sometimes abbreviated SCOTUS, is a one-of-a-kind institution. While a look at the Supreme Court typically focuses on the nine justices themselves, they represent only the top layer of an entire branch of government that includes many administrators, lawyers, and assistants who contribute to and help run the overall judicial system. The Court has its own set of rules for choosing cases, and it follows a unique set of procedures for hearing them. Its decisions not only affect the outcome of the individual case before the justices, but they also create lasting impacts on legal and constitutional interpretation for the future.

LINK TO LEARNING

Supreme Court of the United States Procedures: Crash Course Government and Politics #20

*Watch this video to learn more about the Supreme Court.

The Structure of the Supreme Court

The original court in 1789 had six justices, but Congress set the number at nine in 1869, and it has remained there ever since. There is one chief justice, who is the lead or highest-ranking judge on the Court, and eight associate justices. All nine serve lifetime terms, after successful nomination by the president and confirmation by the Senate. There was discussion of expanding the court during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency and also during the 2020 presidential election. Nothing has come of court expansion, however.

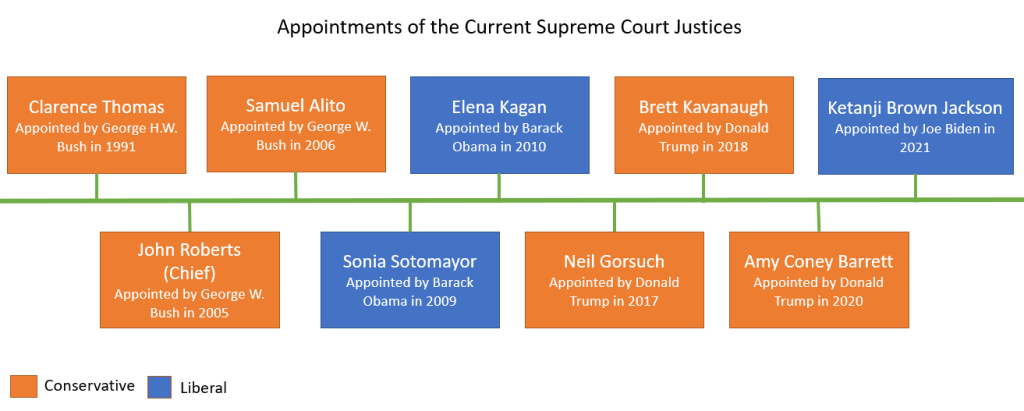

The current court is fairly diverse in terms of gender, religion (Christians and Jews), ethnicity (African, European and Latina or Hispanic Americans), and ideology, as well as length of tenure. Some justices have served for three decades, whereas others were only recently appointed by Presidents Trump and Biden. Figure 1 lists the names of the nine justices serving on the Court as of April 2022, along with their year of appointment and the president who nominated them.

Currently, there are six justices who are considered part of the Court’s more conservative wing—Chief Justice Roberts and Associate Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett—while two are considered more liberal-leaning—Justices Sotomayor and Kagan. Following the retirement of Justice Stephens, the Senate on April 7, 2022, by a 53-47 vote affirmed Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson as the 116th Justice. Dr. Jackson is the first and only justice with experience as a public defender, and she is the first Black woman to serve on the court.

LINKS TO LEARNING

While not formally connected with the public the way elected leaders are, the Supreme Court nonetheless offers visitors a great deal of information at its official website.

For unofficial summaries of recent Supreme Court cases or news about the Court, visit the Oyez website or SCOTUS blog.

In fact, none of the justices works completely in an ideological bubble. While their numerous opinions have revealed certain ideological tendencies, they still consider each case as it comes to them, and they don’t always rule in a consistently predictable or expected way. Furthermore, they don’t work exclusively on their own. Each justice has three or four law clerks, recent law school graduates who temporarily work for the justice, do research, help prepare the justice with background information, and assist with the writing of opinions. The law clerks’ work and recommendations influence whether the justices will choose to hear a case, as well as how they will rule. As the profile below reveals, the role of the clerks is as significant as it is varied.

INSIDER PERSPECTIVE

Profile of a United States Supreme Court Clerk

A Supreme Court clerkship is one of the most sought-after legal positions, giving “thirty-six young lawyers each year a chance to leave their fingerprints all over constitutional law.”[47] A number of current and former justices were themselves clerks, including Chief Justice John Roberts, Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan, and former chief justice William Rehnquist.

Supreme Court clerks are often reluctant to share insider information about their experiences, but it is always fascinating and informative to hear about their jobs. Former clerk Philippa Scarlett, who worked for Justice Stephen Breyer, describes four main responsibilities:[48]

Review the cases: Clerks participate in a “cert. pool” (short for writ of certiorari, a request that the lower court send up its record of the case for review) and make recommendations about which cases the Court should choose to hear.

Prepare the justices for oral argument: Clerks analyze the filed briefs (short arguments explaining each party’s side of the case) and the law at issue in each case waiting to be heard.

Research and draft judicial opinions: Clerks do detailed research to assist justices in writing an opinion, whether it is the majority opinion or a dissenting or concurring opinion.

Help with emergencies: Clerks also assist the justices in deciding on emergency applications to the Court, many of which are applications by prisoners to stay their death sentences and are sometimes submitted within hours of a scheduled execution.

Explain the role of law clerks in the Supreme Court system. What is your opinion about the role they play and the justices’ reliance on them?

How the Supreme Court Selects Cases

The Supreme Court begins its annual session on the first Monday in October and ends late the following June. Every year, there are literally thousands of people who would like to have their case heard before the Supreme Court, but the justices will select only a handful to be placed on the docket, which is the list of cases scheduled on the Court’s calendar. The Court typically accepts fewer than 2 percent of the as many as ten thousand cases it is asked to review every year.[49]

Case names, written in italics, list the name of a petitioner versus a respondent, as in Roe v. Wade, for example.[50] For a case on appeal, you can tell which party lost at the lower level of court by looking at the case name: The party unhappy with the decision of the lower court is the one bringing the appeal and is thus the petitioner, or the first-named party in the case. For example, in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Oliver Brown was one of the thirteen parents who brought suit against the Topeka public schools for discrimination based on racial segregation.

Most often, the petitioner is asking the Supreme Court to grant a writ of certiorari, a request that the lower court send up its record of the case for review. Once a writ of certiorari (cert. for short) has been granted, the case is scheduled on the Court’s docket. The Supreme Court exercises discretion in the cases it chooses to hear, but four of the nine justices must vote to accept a case. This is called the Rule of Four.

For decisions about cert., the Court’s Rule 10 (Considerations Governing Review on Writ of Certiorari) takes precedence.[51] The Court is more likely to grant certiorari when there is a conflict on an issue between or among the lower courts. Examples of conflicts include (1) conflicting decisions among different courts of appeals on the same matter, (2) decisions by an appeals court or a state court conflicting with precedent, and (3) state court decisions that conflict with federal decisions. Occasionally, the Court will fast-track a case that has special urgency, such as Bush v. Gore in the wake of the 2000 election.[52]

Past research indicated that the amount of interest-group activity surrounding a case before it is granted cert. has a significant impact on whether the Supreme Court puts the case on its agenda. The more activity, the more likely the case will be placed on the docket.[53] But more recent research broadens that perspective, suggesting that too much interest-group activity when the Court is considering a case for its docket may actually have diminishing impact and that external actors may have less influence on the work of the Court than they have had in the past.[54] Still, the Court takes into consideration external influences, not just from interest groups but also from the public, from media attention, and from a very key governmental actor—the solicitor general.

The solicitor general is the lawyer who represents the federal government before the Supreme Court: He or she decides which cases (in which the United States is a party) should be appealed from the lower courts and personally approves each one presented. Most of the cases the solicitor general brings to the Court will be given a place on the docket. About two-thirds of all Supreme Court cases involve the federal government.[55]

The solicitor general determines the position the government will take on a case. The attorneys of the office prepare and file the petitions and briefs, and the solicitor general (or an assistant) presents the oral arguments before the Court.

In other cases in which the United States is not the petitioner or the respondent, the solicitor general may choose to intervene or comment as a third party. Before a case is granted cert., the justices will sometimes ask the solicitor general to comment on or file a brief in the case, indicating their potential interest in getting it on the docket. The solicitor general may also recommend that the justices decline to hear a case. Though research has shown that the solicitor general’s special influence on the Court is not unlimited, it remains quite significant. In particular, the Court does not always agree with the solicitor general, and “while justices are not lemmings who will unwittingly fall off legal cliffs for tortured solicitor general recommendations, they nevertheless often go along with them even when we least expect them to.”[56]

Some have credited Donald B. Verrilli, the solicitor general under President Obama, with holding special sway over the five-justice majority ruling on same-sex marriage in June 2015. Indeed, his position that denying same-sex couples the right to marry would mean “thousands and thousands of people are going to live out their lives and go to their deaths without their states ever recognizing the equal dignity of their relationships” became a foundational point of the Court’s opinion, written by then-Justice Anthony Kennedy.[57] With such power over the Court, the solicitor general is sometimes referred to as “the tenth justice.”

Supreme Court Procedures

Once a case has been placed on the docket, briefs, or short arguments explaining each party’s view of the case, must be submitted—first by the petitioner putting forth his or her case, then by the respondent. After initial briefs have been filed, both parties may file subsequent briefs in response to the first. Likewise, people and groups that are not party to the case but are interested in its outcome may file an amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief giving their opinion, analysis, and recommendations about how the Court should rule. Interest groups in particular can become heavily involved in trying to influence the judiciary by filing amicus briefs—both before and after a case has been granted cert. And, as noted earlier, if the United States is not party to a case, the solicitor general may file an amicus brief on the government’s behalf.

With briefs filed, the Court hears oral arguments in cases from October through April. The proceedings are quite ceremonial. When the Court is in session, the robed justices make a formal entrance into the courtroom to a standing audience and the sound of a banging gavel. The Court’s marshal presents them with a traditional chant: “The Honorable, the Chief Justice and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. Oyez! Oyez! Oyez! [Hear ye!] All persons having business before the Honorable, the Supreme Court of the United States, are admonished to draw near and give their attention, for the Court is now sitting. God save the United States and this Honorable Court!”[58] It has not gone unnoticed that the Court, which has defended the First Amendment’s religious protection and the traditional separation of church and state, opens its every public session with a mention of God.

During oral arguments, each side’s lawyers have thirty minutes to make their legal case, though the justices often interrupt the presentations with questions. The justices consider oral arguments not as a forum for a lawyer to restate the merits of the case as written in the briefs, but as an opportunity to get answers to any questions they may have.[59] When the United States is party to a case, the solicitor general (or one of the solicitor general’s assistants) will argue the government’s position; even in other cases, the solicitor general may still be given time to express the government’s position on the dispute.

When oral arguments have been concluded, the justices have to decide the case, and they do so in conference, which is held in private twice a week when the Court is in session and once a week when it is not. The conference is also a time to discuss petitions for certiorari, but for those cases already heard, each justice may state their views on the case, ask questions, or raise concerns. The chief justice speaks first about a case, then each justice speaks in turn, in descending order of seniority, ending with the most recently appointed justice.[60] The judges take an initial vote in private before the official announcement of their decisions is made public.

Oral arguments are open to the public, but cameras are not allowed in the courtroom, so the only picture we get is one drawn by an artist’s hand, an illustration or rendering. Cameras seem to be everywhere today, especially to provide security in places such as schools, public buildings, and retail stores, so the lack of live coverage of Supreme Court proceedings may seem unusual or old-fashioned. Over the years, groups have called for the Court to let go of this tradition and open its operations to more “sunshine” and greater transparency. Nevertheless, the justices have resisted the pressure and remain neither filmed nor photographed during oral arguments.[61]

2.6 Judicial Decision-Making and Implementation by the Supreme Court

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how the Supreme Court decides cases and issues opinions

- Identify the various influences on the Supreme Court

- Explain how the judiciary is checked by the other branches of government

The courts are the least covered and least publicly known of the three branches of government. The inner workings of the Supreme Court and its day-to-day operations certainly do not get as much public attention as its rulings, and only a very small number of its announced decisions are enthusiastically discussed and debated. The Court’s 2015 decision on same-sex marriage was the exception, not the rule, since most court opinions are filed away quietly in the United States Reports, sought out mostly by judges, lawyers, researchers, and others with a particular interest in reading or studying them.

Thus, we sometimes envision the justices formally robed and cloistered away in their chambers, unaffected by the world around them, but the reality is that they are not that isolated, and a number of outside factors influence their decisions. Though they lack their own mechanism for enforcement of their rulings and their power remains checked and balanced by the other branches, the effect of the justices’ opinions on the workings of government, politics, and society in the United States is much more significant than the attention they attract might indicate.

LINK TO LEARNING

Judicial Decisions: Crash Course Government and Politics #22

*Watch this video to learn more about judicial decisions.

Judicial Opinions

Most typically, though, the Court will put forward a majority opinion. If he or she is in the majority, the chief justice decides who will write the opinion. If not, then the most senior justice ruling with the majority chooses the writer. Likewise, the most senior justice in the dissenting group can assign a member of that group to write the dissenting opinion; however, any justice who disagrees with the majority may write a separate dissenting opinion. If a justice agrees with the outcome of the case but not with the majority’s reasoning in it, that justice may write a concurring opinion.

Court decisions are released at different times throughout the Court’s term, but all opinions are announced publicly before the Court adjourns for the summer. Some of the most controversial and hotly debated rulings are released near or on the last day of the term and thus are avidly anticipated.

LINK TO LEARNING

One of the most prominent writers on judicial decision-making in the U.S. system is Dr. Forrest Maltzman of George Washington University. Maltzman’s articles, chapters, and manuscripts, along with articles by other prominent authors in the field, are downloadable at this site.

Influences on the Court

Many of the same players who influence whether the Court will grant cert. in a case, discussed earlier in this chapter, also play a role in its decision-making, including law clerks, the solicitor general, interest groups, and the mass media. But additional legal, personal, ideological, and political influences weigh on the Supreme Court and its decision-making process. On the legal side, courts, including the Supreme Court, cannot make a ruling unless they have a case before them, and even with a case, courts must rule on its facts. Although the courts’ role is interpretive, judges and justices are still constrained by the facts of the case, the Constitution, the relevant laws, and the courts’ own precedent.

Justice’s decisions are influenced by how they define their role as a jurist, with some justices believing strongly in judicial activism, or the need to defend individual rights and liberties, and they aim to stop actions and laws by other branches of government that they see as infringing on these rights. A judge or justice who views the role with an activist lens is more likely to use judicial power to broaden personal liberty, justice, and equality. Still others believe in judicial restraint, which leads them to defer decisions (and thus policymaking) to the elected branches of government and stay focused on a narrower interpretation of the Bill of Rights. These justices are less likely to strike down actions or laws as unconstitutional and are less likely to focus on the expansion of individual liberties. While it is typically the case that liberal actions are described as unnecessarily activist, conservative decisions can be activist as well.

Critics of the judiciary often deride activist courts for involving themselves too heavily in matters they believe are better left to the elected legislative and executive branches. However, as Justice Anthony Kennedy has said, “An activist court is a court that makes a decision you don’t like.”[62]

Another key factor in judicial interpretations is a justice’s judicial philosophy about the Constitution itself. These philosophies involve competing ideas of Originalism and a Living Constitution. The idea of Originalism is the judicial philosophy held by justices that court decisions should consider interpretations based on the original intent of a particular law at the time of its adoption or inception. It values the thinking about the intent of a law as expressed by its authors. The opposing idea of a Living Constitution is the judicial philosophy that suggests that court decisions should heavily consider interpretations based on the realities of modern day or contemporary times that past authors may not consider especially if those realities did not exist in the past. For example, how would conceptions of the law with cyber technology be understood in the context of legal concepts of the framers of the constitution when such technology did not exist?

Justices’ personal beliefs and political attitudes also matter in their decision-making. Although we may prefer to believe a justice can leave political ideology or party identification outside the doors of the courtroom, the reality is that a more liberal-thinking judge may tend to make more liberal decisions and a more conservative-leaning judge may tend toward more conservative ones. Although this is not true 100 percent of the time, and an individual’s decisions are sometimes a cause for surprise, the influence of ideology is real, and at a minimum, it often guides presidents to aim for nominees who mirror their own political or ideological image. It is likely not possible to find a potential justice who is completely apolitical.

And the courts themselves are affected by another “court”—the court of public opinion. Though somewhat isolated from politics and the volatility of the electorate, justices may still be swayed by special-interest pressure, the leverage of elected or other public officials, the mass media, and the general public. As times change and the opinions of the population change, the court’s interpretation is likely to keep up with those changes, lest the courts face the danger of losing their own relevance.

Take, for example, rulings on sodomy laws: In 1986, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the State of Georgia’s ban on sodomy,[63] but it reversed its decision seventeen years later, invalidating sodomy laws in Texas and thirteen other states.[64] No doubt the Court considered what had been happening nationwide: In the 1960s, sodomy was banned in all the states. By 1986, that number had been reduced by about half. By 2002, thirty-six states had repealed their sodomy laws, and most states were only selectively enforcing them. Changes in state laws, along with an emerging LGBTQ movement, no doubt swayed the Court and led it to the reversal of its earlier ruling with the 2003 decision, Lawrence v. Texas.[65] This decision was an especially important one because it meant all prior and existing laws that formally made same-sex relationships illegal were null and void.

Heralded by advocates of gay rights as important progress toward greater equality, the ruling in Lawrence v. Texas illustrates that the Court is willing to reflect upon what is going on in the world. Even with their heavy reliance on precedent and reluctance to throw out past decisions, justices are not completely inflexible and do tend to change and evolve with the times.

GET CONNECTED!

The Importance of Jury Duty

Since judges and justices are not elected, we sometimes consider the courts removed from the public; however, this is not always the case, and there are times when average citizens may get involved with the courts firsthand as part of their decision-making process at either the state or federal levels. At some point, if you haven’t already been called, you may receive a summons for jury duty from your local court system. You may be asked to serve on federal jury duty, such as U.S. district court duty or federal grand jury duty, but service at the local level, in the state court system, is much more common.