Race Discrimination and the Foundations of Equal Protection

OpenStax and Lumen Learning and Collected works

13.1 Introduction to Civil Rights

The U.S Constitution and its founding principles of liberty, equality, and justice are admired and emulated the world over. However, not everyone living in the U.S. has enjoyed the same treatment and freedoms the law promises. When we consider the experiences of women, immigrants, people of color, LGBTQ people, people with disabilities, and other groups, a majority of Americans have been deprived of basic rights and opportunities, and sometimes of citizenship itself. This idea of America is, indeed, a work in progress.

The struggle for civil rights is a story of courageous individuals and social movements awakening fellow Americans, compelling lawmakers, and inspiring the courts to make good on these founding promises. While many changes must still be made, the past one hundred years have seen remarkable progress. Yet, as the rash of thinly-veiled voter suppression bills making their way through state legislatures demonstrate, (Figure 13.1), members of these groups still encounter prejudice, discrimination, and even exclusion from civic life.

What is the difference between civil liberties and civil rights? How did the African American struggle for civil rights evolve? What challenges did women overcome in securing the right to vote, and what obstacles do they and other U.S. groups still face? This chapter addresses these and other questions in exploring the essential concepts of civil rights.

13.2 What Are Civil Rights and How Do We Identify Them?

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define the concept of civil rights

- Describe the standards that courts use when deciding whether a discriminatory law or regulation is unconstitutional

- Identify three core questions for recognizing a civil rights problem

The belief that people should be treated equally under the law is one of the cornerstones of political thought in the United States. Yet not all citizens have been treated equally throughout the nation’s history, and some are treated differently even today. For example, until 1920, nearly all women in the United States lacked the right to vote. Black men received the right to vote in 1870, but as late as 1940, only 3 percent of African American adults living in the South were registered to vote, due largely to laws designed to keep them from the polls.[1] Americans were not allowed to enter into legal marriage with a member of the same sex in many U.S. states until 2015. Some types of unequal treatment are considered acceptable in some contexts, while others are clearly not. No one would consider it acceptable to allow a ten-year-old to vote, because a child lacks the ability to understand important political issues, but all reasonable people would agree that it is wrong to mandate racial segregation or to deny someone voting rights on the basis of race. It is important to understand which types of inequality are unacceptable and why.

Defining Civil Rights

Essentially, civil rights are guarantees by the government that it will treat people equally—particularly people belonging to groups that have historically been denied the same rights and opportunities as others. The due process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution enacted the Declaration of Independence’s proclamation that “all men are created equal” by providing de jure equal treatment under the law. According to Chief Justice Earl Warren in the Supreme Court case of Bolling v. Sharpe (1954), “discrimination may be so unjustifiable as to be violative of due process.”[2] Additional guarantees of equality were provided in 1868 by the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which states, in part, that “No State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Thus, between the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, neither state governments nor the federal government may treat people unequally unless unequal treatment is necessary to maintain important governmental interests such as public safety.

We can contrast civil rights with civil liberties, which are limitations on government power designed to protect our fundamental freedoms. For example, the Eighth Amendment prohibits the application of “cruel and unusual punishments” to those convicted of crimes, a limitation on the power of members of each governmental branch: judges, law enforcement, and lawmakers. As another example, the guarantee of equal protection means the laws and the Constitution must be applied on an equal basis, limiting the government’s ability to discriminate or treat some people differently, unless the unequal treatment is based on a valid reason, such as age. A law that imprisons men twice as long as women for the same offense, or restricting people with disabilities from contacting members of Congress, would treat some people differently from others for no valid reason and would therefore be unconstitutional. According to the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause, “all persons similarly circumstanced shall be treated alike.”[3] If people are not similarly circumstanced, however, they may be treated differently. Asian Americans and Latinos overstaying a visa are similarly circumstanced; however, a blind driver or a ten-year-old driver is differently circumstanced than a sighted, adult driver.

Identifying Discrimination

Laws that treat one group of people differently from others are not always unconstitutional. In fact, the government engages in legal discrimination quite often. In most states, you must be eighteen years old to smoke cigarettes and twenty-one to drink alcohol; these laws discriminate against the young. To get a driver’s license so you can legally drive a car on public roads, you have to be a minimum age and pass tests showing your knowledge, practical skills, and vision. Some public colleges and universities run by the government have an open admission policy, which means the school admits all who apply, but others require that students have a high school diploma or a particular score on the SAT or ACT or a GPA above a certain number. This is a kind of discrimination, because these requirements treat people who do not have a high school diploma or a high enough GPA or SAT score differently. How can the federal, state, and local governments discriminate in all these ways even though the equal protection clause seems to suggest that everyone be treated the same?

The answer to this question lies in the purpose of the discriminatory practice. In most cases when the courts are deciding whether discrimination is unlawful, the government has to demonstrate only that it has a good reason to do so. Unless the person or group challenging the law can prove otherwise, the courts will generally decide the discriminatory practice is allowed. In these cases, the courts are applying the rational basis test. That is, as long as there’s a reason for treating some people differently that is “rationally related to a legitimate government interest,” the discriminatory act or law or policy is acceptable.[4] For example, since letting blind people operate cars would be dangerous to others on the road, the law forbidding them to drive is reasonably justified on the grounds of safety and is therefore allowed even though it discriminates against the blind. Similarly, when universities and colleges refuse to admit students who fail to meet a certain test score or GPA, they can discriminate against students with weaker grades and test scores because these students most likely do not yet possess the knowledge or skills needed to do well in their classes and graduate from the institution. The universities and colleges have a legitimate reason for denying these students entrance.

The courts, however, are much more skeptical when it comes to certain other forms of discrimination. Because of the United States’ history of ethnic, racial, gender, and religious discrimination, the courts apply more stringent rules to policies, laws, and actions that discriminate on these bases (race, ethnicity, gender, religion, or national origin).[5]

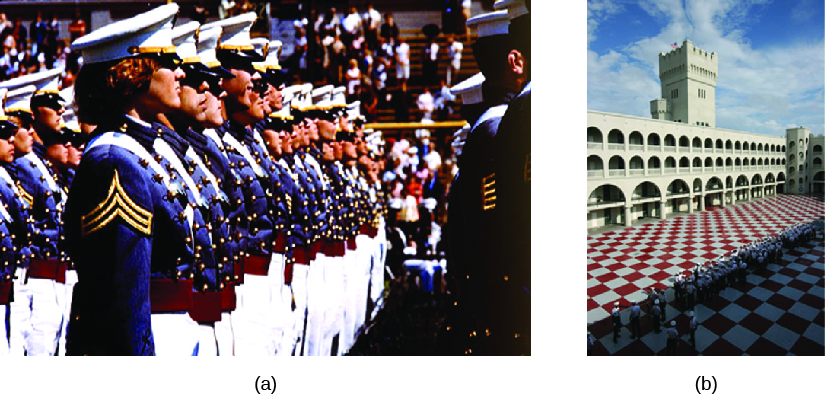

Discrimination based on gender or sex is generally examined with intermediate scrutiny. The standard of intermediate scrutiny was first applied by the Supreme Court in Craig v. Boren (1976) and again in Clark v. Jeter (1988).[6] It requires the government to demonstrate that treating men and women differently is “substantially related to an important governmental objective.” This puts the burden of proof on the government to demonstrate why the unequal treatment is justifiable, not on the individual who alleges unfair discrimination has taken place. In practice, this means laws that treat men and women differently are sometimes upheld, although usually they are not. For example, in the 1980s and 1990s, the courts ruled that states could not operate single-sex institutions of higher education and that such schools, like South Carolina’s military college The Citadel, shown in Figure 13.2, must admit both male and female students.[7] Women in the military are now also allowed to serve in all combat roles, although the courts have continued to allow the Selective Service System (the draft) to register only men and not women.[8]

Discrimination against members of racial, ethnic, or religious groups or those of various national origins is reviewed to the greatest degree by the courts, which apply the strict scrutiny standard in these cases. Under strict scrutiny, the burden of proof is on the government to demonstrate that there is a compelling governmental interest in treating people from one group differently from those who are not part of that group—the law or action can be “narrowly tailored” to achieve the goal in question, and that it is the “least restrictive means” available to achieve that goal.[9] In other words, if there is a non-discriminatory way to accomplish the goal in question, discrimination should not take place. In the modern era, laws and actions that are challenged under strict scrutiny have rarely been upheld. Strict scrutiny, however, was the legal basis for the Supreme Court’s 1944 upholding of the legality of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, discussed later in this chapter.[10] Finally, affirmative action consists of government programs and policies designed to benefit members of groups historically subject to discrimination. Much of the controversy surrounding affirmative action is about whether strict scrutiny should be applied to these cases.

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn about affirmative action.

Putting Civil Rights in the Construction

The aftermath of the Civil War marked a turning point for civil rights. The Republican majority in Congress was enraged by the actions of the reconstituted governments of the southern states. In these states, many former Confederate politicians and their sympathizers returned to power and attempted to circumvent the Thirteenth Amendment’s freeing of enslaved men and women by passing laws known as the Black codes. These laws were designed to reduce formerly enslaved people to the status of serfs or indentured servants. Black people were not just denied the right to vote, but also could be arrested and jailed for vagrancy or idleness if they lacked jobs. Black people were excluded from public schools and state colleges and were subject to violence at the hands of White people (Figure 13.3).[11]

![An image of a sketch of a building on fire. Several people are standing outside the building. Some of the people are armed. At the bottom of the image reads “Scenes in Memphis, Tennessee, during the riot—burning a freedmen’s school-house. [Sketched by A. R. W.]”.](https://uark.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/116/2025/08/fig-5-3.jpeg)

To override the southern states’ actions, lawmakers in Congress proposed two amendments to the Constitution designed to give political equality and power to formerly enslaved people. Once passed by Congress and ratified by the necessary number of states, these became the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. In addition to including the equal protection clause as noted above, the Fourteenth Amendment also was designed to ensure that the states would respect the civil liberties of freed people. The Fifteenth Amendment was proposed to secure the right to vote for Black men, which will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Identifying Civil Rights Issues

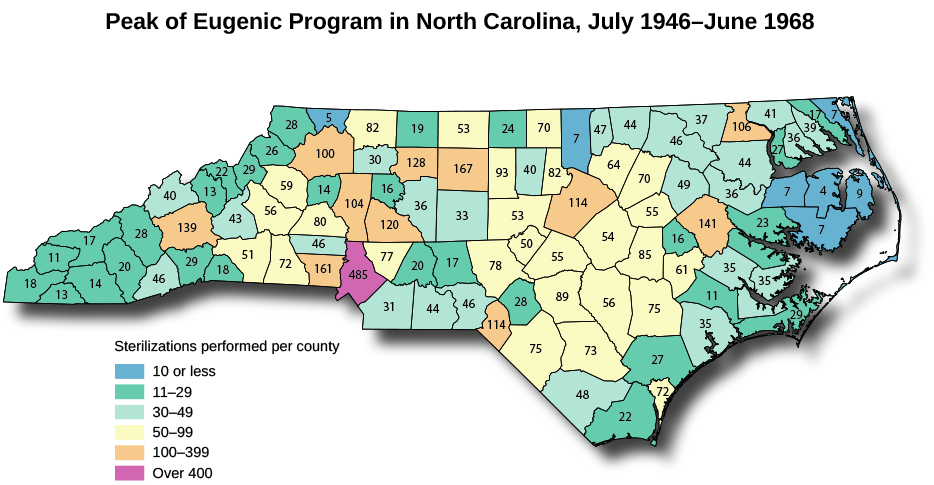

Looking back, it’s relatively easy to identify civil rights issues that arose, looking into the future is much harder. For example, few people fifty years ago would have identified the rights of gay or transgender Americans as an important civil rights issue, or predicted it would become one. Similarly, in past decades the rights of those with disabilities, particularly intellectual disabilities, were often ignored by the public at large. Many people with disabilities were institutionalized and given little further thought, and until very recently, laws remained on the books in some states allowing those with intellectual or developmental disabilities to be subject to forced sterilization.[12] Today, most of us view this treatment as barbaric.

Clearly, then, new civil rights issues can emerge over time. How can we, as citizens, identify them as they emerge and distinguish genuine claims of discrimination from claims by those who have merely been unable to convince a majority to agree with their viewpoints? For example, how do we decide if sixteen-year-olds are discriminated against because they are not allowed to vote, as some U.S. lawmakers are starting to suggest? We can identify true discrimination by applying the following analytical process:

- Which groups? First, identify the group of people who are facing discrimination.

- Which right(s) are threatened? Second, what right or rights are being denied to members of this group?

- What do we do? Third, what can the government do to bring about a fair situation for the affected group? Is proposing and enacting such a remedy realistic?

GET CONNECTED!

Join the Fight for Civil Rights

One way to get involved in the fight for civil rights is to stay informed. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) is a not-for-profit advocacy group based in Montgomery, Alabama. Lawyers for the SPLC specialize in civil rights litigation and represent many people whose rights have been violated, from victims of hate crimes to undocumented immigrants. They provide summaries of important civil rights cases under their Docket section.

Activity: Visit the SPLC website to find current information about a variety of different hate groups. In what part of the country do hate groups seem to be concentrated? Where are hate incidents most likely to occur? What might be some reasons for this?

LINK TO LEARNING

Civil rights institutes are found throughout the United States and especially in the south. One of the most prominent civil rights institutes is the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, which is located in Alabama

13.3 The African American Struggle for Equality

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify key events in the history of African American civil rights

- Explain how the courts, Congress, and the executive branch supported the civil rights movement

- Describe the role of grassroots efforts in the civil rights movement

Many groups in U.S. history have sought recognition as equal citizens. Although each group’s efforts have been notable and important, arguably the greatest, longest, and most violent struggle remains that of African Americans, whose dehumanization was even written into the text of the Constitution in the clause counting them as three fifths of a person. Their fight for freedom and equality provided the legal and moral foundation for others who sought recognition of their equality later on.

Slavery and the Civil War

In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson made the radical statement that “all men are created equal” and “are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Yet, like other wealthy landowners of his time, Jefferson also owned dozens of other human beings as his personal property. He recognized this contradiction, personally considered the institution of slavery to be a “hideous blot” on the nation, and agreed to free those he held in bondage upon his death.[13] However, to forge a political union that would stand the test of time, he and the other founders—and later the framers of the Constitution—chose not to address the issue in any definitive way. Political support for abolition was very much a minority stance in the United States at the time, although after the Revolution many of the northern states followed the European example of fifty years prior in abolishing slavery.[14]

As the new United States expanded westward, however, the issue of slavery became harder to ignore and ignited much controversy. Many opponents of slavery were willing to accept the institution if it remained largely confined to the South but did not want it to spread westward. They feared the expansion of slavery would lead to the political dominance of the South over the North and would deprive small farmers in the newly acquired western territories who could not afford to enslave others.[15] Abolitionists, primarily in the North, argued that slavery was immoral and contrary to the nation’s values and demanded an end to it.

The spread of slavery into the West seemed inevitable, however, following the Supreme Court’s 1857 ruling in the case Dred Scott v. Sandford.[16] The justices rejected Scott’s argument that though he had been born into slavery, his time spent in free states and territories where slavery had been banned by the federal government had made him a free man. In fact, the Court’s majority stated that Scott had no legal right to sue for his freedom at all because Black people (whether free or enslaved) were not, and could not become, U.S. citizens. Thus, Scott lacked the standing to even appear before the court. The Court also held that Congress lacked the power to decide whether slavery would be permitted in a territory that had been acquired after the Constitution was ratified. This decision had the effect of prohibiting the federal government from passing any laws that would limit the expansion of slavery into any part of the West.

Ultimately, of course, the issue was decided by the Civil War (1861–1865), with the southern states seceding to defend “states’ rights,” specifically, the purported right to own human property, without federal interference.[17] Although at the beginning of the war, President Abraham Lincoln had been willing to allow slavery to continue in the South to preserve the Union, he changed his policies regarding abolition over the course of the war. The first step was the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 (Figure 13.4). Although it stated “all persons held as slaves . . . henceforward shall be free,” the proclamation was limited in effect to the states that had rebelled. Enslaved people in states that had remained within the Union, such as Maryland and Delaware were not set free, nor were they in parts of the Confederacy already occupied by the Union army. Although enslaved people in rebel states were freed by federal decree, the relatively small Union troop presence made it impossible to enforce their release from bondage.[18]

Reconstruction

At the end of the Civil War, the South entered a period called Reconstruction (1865–1877) during which state governments were reorganized before the rebellious states were allowed to be readmitted to the Union. As part of this process, the Republican Party pushed for a permanent end to slavery. A constitutional amendment to this effect was passed by the House of Representatives in January of 1865, after having already been approved by the Senate in April of 1864, and it was ratified in December of 1865 as the Thirteenth Amendment. The amendment’s first section states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” In effect, this amendment outlawed slavery in the United States.

The changes wrought by the Fourteenth Amendment were more extensive. In addition to introducing the equal protection clause to the Constitution, this amendment also extended the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the states, required the states to respect the privileges or immunities of all citizens, and, for the first time, defined citizenship at the national and state levels. People could no longer be excluded from citizenship based solely on their race. Although lack of political or judicial action rendered some of these provisions toothless, others were pivotal in the expansion of civil rights.

The Fifteenth Amendment stated that people could not be denied the right to vote based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This construction allowed states to continue to decide the qualifications of voters as long as those qualifications seemed to be race-neutral. Thus, while states could not deny Black people the right to vote on the basis of race, they could deny it on any number of arbitrary grounds such as literacy, landownership, affluence, or political knowledge.

Although the immediate effect of these provisions was quite profound, over time the Republicans in Congress gradually lost interest in pursuing Reconstruction policies, and the Reconstruction ended with the end of military rule in the South and the withdrawal of the Union army in 1877.[19] Following the army’s removal, political control of the South fell once again into the hands of White men, and violence was used to discourage Black people from exercising the rights they had been granted.[20] The revocation of voting rights, or disenfranchisement, took a number of forms; not every southern state used the same methods, and some states used more than one, but they all disproportionately affected Black voter registration and turnout.[21]

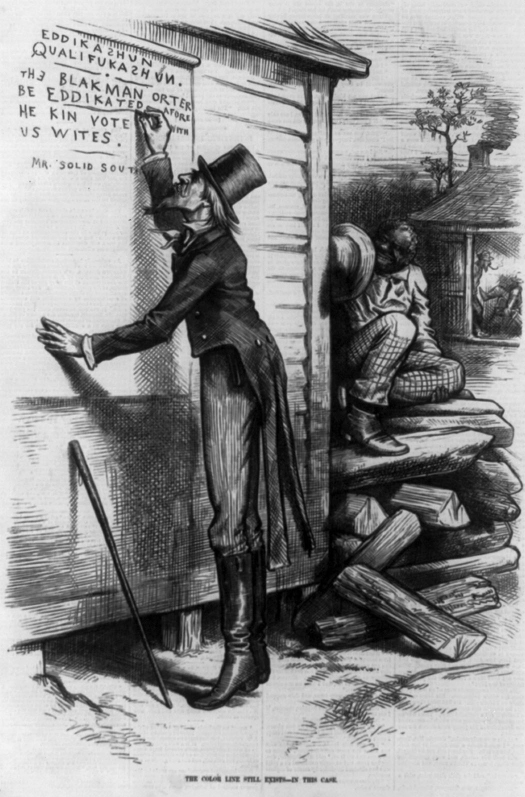

Perhaps the most famous of the tools of disenfranchisement were literacy tests and understanding tests. Literacy tests, which had been used in the North since the 1850s to disqualify naturalized European immigrants from voting, called on the prospective voter to demonstrate his (and later, her) ability to read a particular passage of text. However, since voter registration officials had discretion to decide what text the voter was to read, they could give easy passages to voters they wanted to register (typically, white people) and more difficult passages to those whose registration they wanted to deny (typically, Black people). Understanding tests required the prospective voter to explain the meaning of a particular passage of text, often a provision of the U.S. Constitution, or answer a series of questions related to citizenship. Again, since the official examining the prospective voter could decide which passage or questions to choose, the difficulty of the test might vary dramatically between African American and white applicants.[22] Even had these tests been administered fairly and equitably, however, most African Americans would have been at a huge disadvantage, because few had been taught to read. Although schools for Black people had existed in some places, southern states had made it largely illegal to teach enslaved people to read and write. At the beginning of the Civil War, only 5 percent of Black people could read and write, and most of them lived in the North.[23] Some were able to take advantage of educational opportunities after they were freed, but many were not able to gain effective literacy.

In some states, poorer, less-literate white voters feared being disenfranchised by the literacy and understanding tests. Some states introduced a loophole, known as the grandfather clause, to allow less literate white people to vote. The grandfather clause exempted those who had been allowed to vote in that state prior to the Civil War and their descendants from literacy and understanding tests.[24] Because Black people were not allowed to vote prior to the Civil War, but most White men had been voting at a time when there were no literacy tests, this loophole allowed most illiterate white people to vote (Figure 13.5) while leaving obstacles in place for Black people who wanted to vote as well. Time limits were often placed on these provisions because state legislators realized that they might quickly be declared unconstitutional, but they lasted long enough to allow illiterate White men to register to vote.[25]

In states where the voting rights of poor white people were less of a concern, another tool for disenfranchisement was the poll tax (Figure 13.6). This was an annual per-person tax, typically one or two dollars (on the order of $20 to $50 today), that a person had to pay to register to vote. People who didn’t want to vote didn’t have to pay, but in several states the poll tax was cumulative, so if you decided to vote you would have to pay not only the tax due for that year but any poll tax from previous years as well. Because formerly enslaved people were usually quite poor, they were less likely than White men to be able to pay poll taxes.[26]

![An image of a receipt. The receipt reads “State of Louisiana—Parish of Jefferson. Office of Sherriff and Tax Collector. Received of A. S. White resident of [sic] Ward, the sum of one dollar, poll tax for the year 1917 for the support of public schools”.](https://uark.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/116/2025/08/fig-5-6.jpeg)

Although these methods were usually sufficient to ensure that Black people were kept away from the polls, some dedicated African Americans did manage to register to vote despite the obstacles placed in their way. To ensure their vote was largely meaningless, the White elites used their control of the Democratic Party to create the white primary: primary elections in which only White people were allowed to vote. The state party organizations argued that as private groups, rather than part of the state government, they had no obligation to follow the Fifteenth Amendment’s requirement not to deny the right to vote on the basis of race. Furthermore, they contended, voting for nominees to run for office was not the same as electing those who would actually hold office. So they held primary elections to choose the Democratic nominee in which only White citizens were allowed to vote.[27] Once the nominee had been chosen, they might face token opposition from a Republican or minor-party candidate in the general election, but since White voters had agreed beforehand to support whoever won the Democrats’ primary, the outcome of the general election was a foregone conclusion.

With Black people effectively disenfranchised, the restored southern state governments undermined guarantees of equal treatment in the Fourteenth Amendment. They passed laws that excluded African Americans from juries and allowed the imprisonment and forced labor of “idle” Black citizens. The laws also called for segregation of White and Black people in public places under the doctrine known as “separate but equal.” As long as nominally equal facilities were provided for both races, it was legal to require members of each race to use the facilities designated for them. Similarly, state and local governments passed laws limiting neighborhoods in which Black and White people could live. Collectively, these discriminatory laws came to be known as Jim Crow laws. The Supreme Court upheld the separate but equal doctrine in 1896 in Plessy v. Ferguson, inconsistent with the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, and allowed segregation to continue.[28]

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn about equal protection and the context surrounding the history leading to the Civil Rights movement and greater equality for African-Americans and blacks in the United State.

Civil Rights in the Courts

The NAACP soon focused on a strategy of overturning Jim Crow laws through the courts. Perhaps its greatest series of legal successes consisted of its efforts to challenge segregation in education. Early cases brought by the NAACP dealt with racial discrimination in higher education. In 1938, the Supreme Court essentially gave states a choice: they could either integrate institutions of higher education, or they could establish an equivalent university or college for African Americans.[30] Southern states chose to establish colleges for Black people rather than allow them into all-White state institutions. Although this ruling expanded opportunities for professional and graduate education in areas such as law and medicine for African Americans by requiring states to provide institutions for them to attend, it nevertheless allowed segregated colleges and universities to continue to exist.

LINK TO LEARNING

The NAACP was pivotal in securing African American civil rights and today continues to address civil rights violations, such as police brutality and the disproportionate percentage of African American people that die under the death penalty.

The landmark court decision of the judicial phase of the civil rights movement settled the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954.[31] In this case, the Supreme Court unanimously overturned its decision in Plessy v. Ferguson as it pertained to public education, stating that a separate but equal education was a logical impossibility. Even with the same funding and equivalent facilities, a segregated school could not have the same teachers or environment as the equivalent school for another race. The court also rested its decision in part on social science studies suggesting that racial discrimination led to feelings of inferiority among Black children. The only way to dispel this sense of inferiority was to end segregation and integrate public schools.

It is safe to say this ruling was controversial. While integration of public schools took place without much incident in some areas of the South, particularly where there were few Black students, elsewhere, it was confrontational—or nonexistent. In recognition of the fact that southern states would delay school integration for as long as possible, civil rights activists urged the federal government to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision. Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph organized a Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom in Washington, DC, on May 17, 1957, in which approximately twenty-five thousand African Americans participated.[32]

A few months later, in Little Rock, Arkansas, governor Orval Faubus resisted court-ordered integration and mobilized National Guard troops to keep Black students out of Central High School. President Eisenhower then called up the Arkansas National Guard for federal duty (essentially taking the troops out of Faubus’s hands) and sent soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division to escort students to and from classes, as shown in Figure 13.7. To avoid integration, Faubus closed four high schools in Little Rock the following school year.[33]

In Virginia, state leaders employed a strategy of “massive resistance” to school integration, which led to the closure of a large number of public schools across the state, some for years.[34] Although de jure segregation, segregation mandated by law, had ended on paper, in practice, few efforts were made to integrate schools in most school districts with substantial Black student populations until the late 1960s. Many White southerners who objected to sending their children to school with Black students then established private academies that admitted only White students; many of these schools remain overwhelmingly White today.[35]

School and other segregation was and is hardly limited to the South. Many neighborhoods in northern cities remain segregated by virtue of “red lining” districts where minorities were allowed and not allowed to live. Restrictive real estate covenants bound White residents to not sell their houses to African Americans and sometimes not to Chinese, Japanese, Mexicans, Filipinos, Jews, and other ethnic minorities. In New York City in the late 1950s, a group of activist parents led by Mae Mallory protested the inadequate schools in their neighborhood; a court ruled that New York was engaging in de facto segregation, and forced the city to institute policies that would provide more equitable access.[36] More recently, banks have been fined for not lending to people of color to buy homes and start business at rates commensurate with similarly situated prospective White borrowers. Relegation of minority residents to less desirable neighborhoods has the practical effect of diminishing both generational wealth, and the tax base needed to build, maintain, and improve schools and other institutions that might hasten equality and integration.

In the postwar era of White flight, however, the Supreme Court had been evolving into a more progressive force in the promotion and preservation of civil rights. In the case of Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), the Supreme Court held that while such covenants did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment because they consisted of agreements between private citizens, their provisions could not be enforced by courts.[37] Because state courts are government institutions and the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the government from denying people equal protection of the law, the courts’ enforcement of such covenants would be a violation of the amendment. Thus, if a White family chose to sell its house to a Black family and the other homeowners in the neighborhood tried to sue the seller, the court would not hear the case. In 1967, the Supreme Court struck down a Virginia law that prohibited interracial marriage in Loving v. Virginia.[38]

Legislating Civil Rights

Beyond these favorable court rulings, however, progress toward equality for African Americans remained slow in the 1950s. In 1962, Congress proposed what later became the Twenty-Fourth Amendment, which banned the poll tax in elections to federal (but not state or local) office; the amendment went into effect after being ratified in early 1964. Several southern states continued to require residents to pay poll taxes in order to vote in state elections until 1966 when, in the case of Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, the Supreme Court declared that requiring payment of a poll tax in order to vote in an election at any level was unconstitutional.[39]

The slow rate of progress led to frustration within the Black community. Newer, grassroots organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) challenged the NAACP’s position as the leading civil rights organization and questioned its legal-focused strategy. These newer groups tended to prefer more confrontational approaches, including the use of direct action campaigns relying on marches and demonstrations. The strategies of nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience, or the refusal to obey an unjust law, had been effective in the campaign led by Mahatma Gandhi to liberate colonial India from British rule in the 1930s and 1940s. Civil rights pioneers adopted these measures in the 1955–1956 Montgomery bus boycott. After Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a White person and was arrested, a group of Black women carried out a day-long boycott of Montgomery’s public transit system. This boycott was then extended for over a year and overseen by union organizer E. D. Nixon. The effort desegregated public transportation in that city.[40]

Direct action also took such forms as the sit-in campaigns to desegregate lunch counters that began in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960, and the 1961 Freedom Rides in which Black and White volunteers rode buses and trains through the South to enforce a 1946 Supreme Court decision that desegregated interstate transportation (Morgan v. Virginia).[41] While such focused campaigns could be effective, they often had little impact in places where they were not replicated. In addition, some of the campaigns led to violence against both the campaigns’ leaders and ordinary people; Rosa Parks, a longtime NAACP member and graduate of the Highlander Folk School for civil rights activists, whose actions had begun the Montgomery boycott, received death threats, E. D. Nixon’s home was bombed, and the Freedom Riders were attacked in Alabama.[42]

As the campaign for civil rights continued and gained momentum, President John F. Kennedy called for Congress to pass new civil rights legislation, which began to work its way through Congress in 1963. The resulting law (pushed heavily and then signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson after Kennedy’s assassination) was the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which had wide-ranging effects on U.S. society. Not only did the act outlaw government discrimination and the unequal application of voting qualifications by race, but it also, for the first time, outlawed segregation and other forms of discrimination by most businesses that were open to the public, including hotels, theaters, and restaurants that were not private clubs. It outlawed discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, religion, sex, or national origin by most employers, and it created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to monitor employment discrimination claims and help enforce this provision of the law. The provisions that affected private businesses and employers were legally justified not by the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws but instead by Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce.[43]

Even though the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had a monumental impact over the long term, it did not end efforts by many southern White people to maintain the White-dominated political power structure in the region. Progress in registering African American voters remained slow in many states despite increased federal activity supporting it, so civil rights leaders including Martin Luther King, Jr. decided to draw the public eye to the area where the greatest resistance to voter registration drives were taking place. The SCLC and SNCC particularly focused their attention on the city of Selma, Alabama, which had been the site of violent reactions against civil rights activities.

The organizations’ leaders planned a march from Selma to Montgomery in March 1965. Their first attempt to march was violently broken up by state police and sheriff’s deputies (Figure 13.8). The second attempt was aborted because King feared it would lead to a brutal confrontation with police and violate a court order from a federal judge who had been sympathetic to the movement in the past. That night, three of the marchers, White ministers from the north, were attacked and beaten with clubs by members of the Ku Klux Klan; one of the victims died from his injuries. Televised images of the brutality against protesters and the death of a minister led to greater public sympathy for the cause. Eventually, a third march was successful in reaching the state capital of Montgomery.[44]

LINK TO LEARNING

The 1987 PBS documentary Eyes on the Prize won several Emmys and other awards for its coverage of major events in the civil rights movement, including the Montgomery bus boycott, the battle for school integration in Little Rock, the march from Selma to Montgomery, and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s leadership of the march on Washington, DC.

The events at Selma galvanized support in Congress for a follow-up bill solely dealing with the right to vote. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 went beyond previous laws by requiring greater oversight of elections by federal officials. Literacy and understanding tests, and other devices used to discriminate against voters on the basis of race, were banned. The Voting Rights Act proved to have much more immediate and dramatic effect than the laws that preceded it; what had been a fairly slow process of improving voter registration and participation was replaced by a rapid increase of Black voter registration rates—although White registration rates increased over this period as well.[45] To many people’s way of thinking, however, the Supreme Court turned back the clocks when it gutted a core aspect of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder (2013).[46] No longer would states need federal approval to change laws and policies related to voting. Indeed, many states with a history of voter discrimination quickly resumed restrictive practices with laws requiring photo ID; limiting early voting, ballot drop-off locations, and hours; and making registering and waiting to vote more onerous. Some of the new restrictions are already being challenged in the courts.[47]

Not all African Americans in the civil rights movement were comfortable with gradual change. Instead of using marches and demonstrations to change people’s attitudes, calling for tougher civil rights laws, or suing for their rights in court, they favored more immediate action to prevent White oppression and protect their communities. Men like Malcolm X, and groups like the Black Panthers were willing to use other means to achieve their goals (Figure 13.9).[48] Faced with continual violence at the hands of police and acts of terrorism like the bombing of a Black church in Alabama that killed four girls, Malcolm X expressed significant distrust of White people. He sought to raise the self-esteem of Black people and advocated for their separation from the United States through eventual emigration to Africa. In general, Malcolm X rejected the mainstream civil right’s movement’s integration and assimilation approach, and laid the foundation for the Black Power movement, which sought self-determination and independence for Black people. His position was attractive to many young African Americans, especially after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968.

Continuing Challenges for African Americans

The civil rights movement for African Americans did not end with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. For the last fifty years, the African American community has faced challenges related to both past and current discrimination, and progress on both fronts remains slow, uneven, and often frustrating.

Legacies of the de jure segregation of the past remain in much of the United States. Many Black people still live in predominantly Black neighborhoods where their ancestors were forced by laws and housing covenants to live.[49] Even those who live in the suburbs, once largely populated only by White people, tend to live in suburbs that are mostly populated by Black people.[50] Some two million African American young people attend schools whose student body is composed almost entirely of students of color.[51] During the late 1960s and early 1970s, efforts to tackle these problems were stymied by large-scale public opposition, not just in the South but across the nation. Attempts to integrate public schools through the use of busing—transporting students from one segregated neighborhood to another to achieve more racially balanced schools—were particularly unpopular and helped contribute to “White flight” from cities to the suburbs.[52] This White flight has created de facto segregation, a form of segregation that results from the choices of individuals to live in segregated communities without government action or support.

Today, a lack of well-paying jobs in many urban areas, combined with the poverty resulting from the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow era terror, and persistent racism, has trapped many Black people in under-served neighborhoods with markedly lower opportunity and life expectancy.[53] While the Civil Rights Act of 1964 created opportunities for members of the Black middle class to advance economically and socially, and to live in the same neighborhoods as the White middle class, their departure left many Black neighborhoods mired in poverty and without the strong community ties that existed during the era of legal segregation. Many of these neighborhoods continue to suffer from high rates of crime and violence.[54] Police also appear, consciously or subconsciously, to engage in racial profiling: singling out Black people (and Latino people) for greater attention than members of other racial and ethnic groups, as former FBI director James B. Comey and former New York police commissioner Bill Bratton have admitted.[55] When incidents of real or perceived injustice arise, as recently occurred after a series of deaths of Black people at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri; Staten Island, New York; Baltimore, Maryland; Louisville, Kentucky; and Minneapolis, Minnesota, many African Americans turn to the streets to protest because they feel abandoned or ignored by politicians of all races.

While the public mood may have shifted toward greater concern about economic inequality in the United States, substantial policy changes to immediately improve the economic standing of African Americans in general have not followed. The Obama administration proposed new rules under the Fair Housing Act that were intended to lead to more integrated communities in the future; however, the Trump administration repeatedly sought to weaken the Fair Housing Act, primarily through lack of enforcement of existing regulations.[56] Meanwhile, grassroots movements to improve neighborhoods and local schools have taken root in many Black communities across America, and perhaps in those movements is the hope for greater future progress.

Other recent movements are more troubling, notably the increased presence and influence of White nationalism throughout the country. This movement espouses White supremacy and does not shrink from the threat or use of violence to achieve it. Such violence occurred in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017, when various White supremacist groups and alt-right forces joined together in a “Unite the Right” rally (Figure 13.10). This rally included chants and racial slurs against African Americans and Jews. Those rallying clashed with counter-protestors, one of whom died when an avowed Neo-Nazi deliberately drove his car into a group of peaceful protestors. He has since been convicted and sentenced to life in prison for his actions. This event sent shockwaves through U.S. politics, as leaders tried to grapple with the significance of the event. President Trump said that “good people existed on both sides of the clash,” and later, for inciting a group of protesters to storm the Capitol after a rally of his in which he repeated the false claim that the election had been stolen from him.[57]

FINDING A MIDDLE GROUND

Affirmative Action

One of the major controversies regarding race in the United States today is related to affirmative action, the practice of ensuring that members of historically disadvantaged or underrepresented groups have equal access to opportunities in education, the workplace, and government contracting. The phrase affirmative action originated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Executive Order 11246, and it has drawn controversy ever since. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination in employment, and Executive Order 11246, issued in 1965, forbade employment discrimination not only within the federal government but by federal contractors and contractors and subcontractors who received government funds.

Clearly, Black people, as well as other groups, have been subject to discrimination in the past and present, limiting their opportunity to compete on a level playing field with those who face no such challenge. Opponents of affirmative action, however, point out that many of its beneficiaries are ethnic minorities from relatively affluent backgrounds, while White and Asian Americans who grew up in poverty are expected to succeed despite facing challenges related to their socioeconomic status and those related to educational issues in lower income areas.

Because affirmative action attempts to redress discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity, it is generally subject to the strict scrutiny standard, which means the burden of proof is on the government to demonstrate the necessity of racial discrimination to achieve a compelling governmental interest. In 1978, in Bakke v. California, the Supreme Court upheld affirmative action and said that colleges and universities could consider race when deciding whom to admit but could not establish racial quotas.[58] In 2003, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the Bakke decision in Grutter v. Bollinger, which said that taking race or ethnicity into account as one of several factors in admitting a student to a college or university was acceptable, but a system setting aside seats for a specific quota of minority students was not.[59] All these issues are back under discussion in the Supreme Court with the re-arguing of Fisher v. University of Texas.[60] In Fisher v. University of Texas (2013, known as Fisher I), University of Texas student Abigail Fisher brought suit to declare UT’s race-based admissions policy as inconsistent with Grutter. The court did not see the UT policy that way and allowed it, so long as it remained narrowly tailored and not quota-based. Fisher II (2016) was decided by a 4–3 majority. It allowed race-based admissions, but required that the utility of such an approach had to be re-established on a regular basis.

Should race be a factor in deciding who will be admitted to a particular college? Why or why not?

13.4 The Fight for Women’s Rights

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe early efforts to achieve rights for women

- Explain why the Equal Rights Amendment failed to be ratified

- Describe the ways in which women acquired greater rights in the twentieth century

- Analyze why women continue to experience unequal treatment

Along with African Americans, women of all races and ethnicities have long been discriminated against in the United States, and the women’s rights movement began at the same time as the movement to abolish slavery in the United States. Indeed, the women’s movement came about largely as a result of the difficulties women encountered while trying to abolish slavery. The trailblazing Seneca Falls Convention for women’s rights was held in 1848, a few years before the Civil War. But the abolition and African American civil rights movements largely eclipsed the women’s movement throughout most of the nineteenth century. Women began to campaign actively again in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and another movement for women’s rights began in the 1960s.

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn about the sex discrimination and changes in women’s rights through U.S. history.

The Early Women’s Rights Movement and Women’s Suffrage

Following the Revolution, women’s conditions did not improve. Women were not granted the right to vote by any of the states except New Jersey, which at first allowed all taxpaying property owners to vote. However, in 1807, the law changed to limit the vote to men.[63] Changes in property laws actually hurt women by making it easier for their husbands to sell their real property without their consent.

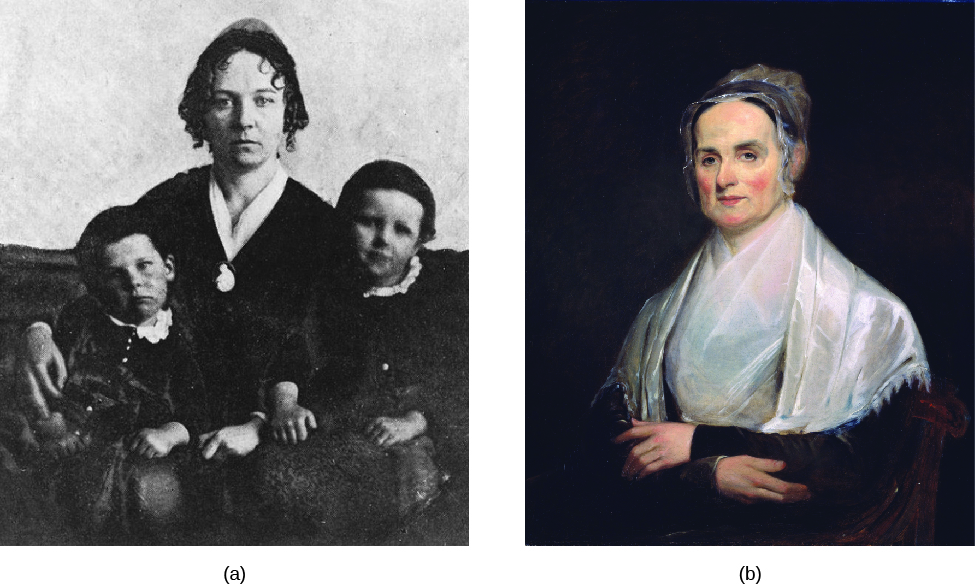

Although women had few rights, they nevertheless played an important role in transforming American society. This was especially true in the 1830s and 1840s, a time when numerous social reform movements swept across the United States. In 1832, for example, African American writer and activist Maria W. Stewart became the first American-born woman to give a speech to a mixed audience. While there was racism within the suffrage movement, including calls for segregated marches and a lack of scrutiny on the topic of lynchings, many women were active in the abolition movement and the temperance movement, which tried to end the excessive consumption of liquor.[64] They often found they were hindered in their efforts, however, either by the law or by widely held beliefs that they were weak, silly creatures who should leave important issues to men.[65] One of the leaders of the early women’s movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton (Figure 13.11), was shocked and angered when she sought to attend an 1840 antislavery meeting in London, only to learn that women would not be allowed to participate and had to sit apart from the men. At this convention, she made the acquaintance of another American woman abolitionist, Lucretia Mott (Figure 13.11), who was also appalled by the male reformers’ treatment of women.[66]

In 1848, Stanton and Mott called for a women’s rights convention, the first ever held specifically to address the subject, at Seneca Falls, New York. At the Seneca Falls Convention, Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments, which was modeled after the Declaration of Independence and proclaimed women were equal to men and deserved the same rights. Among the rights Stanton wished to see granted to women was suffrage, the right to vote. When called upon to sign the Declaration, many of the delegates feared that if women demanded the right to vote, the movement would be considered too radical and its members would become a laughingstock. The Declaration passed, but the resolution demanding suffrage was the only one that did not pass unanimously.[67]

Along with other feminists (advocates of women’s equality), such as her friend and colleague Susan B. Anthony, Stanton fought for rights for women besides suffrage, including the right to seek higher education. As a result of their efforts, several states passed laws that allowed married women to retain control of their property and let divorced women keep custody of their children.[68] Amelia Bloomer, another activist, also campaigned for dress reform, believing women could lead better lives and be more useful to society if they were not restricted by voluminous heavy skirts and tight corsets.

The women’s rights movement attracted many women who, like Stanton and Anthony, were active in either the temperance movement, the abolition movement, or both movements. Sarah and Angelina Grimke, the daughters of a wealthy slaveholding family in South Carolina, became first abolitionists and then women’s rights activists.[69] Prominent Black and formerly enslaved women such as Sojourner Truth, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Mary Anne Shadd Cary joined the women’s movement after establishing themselves as key figures in the abolition movement. These women were known for direct, unorthodox, and effective arguments for the suffragist cause. Truth’s “Ain’t I A Woman” speech is among the most well known of the movement, and Cary, a lawyer, delivered a critical equality argument before the Senate Judiciary Committee..

Following the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, the women’s rights movement fragmented. Stanton and Anthony denounced the Fifteenth Amendment because it granted voting rights only to Black men and not to women of any race.[70] The fight for women’s rights did not die, however. In 1869, Stanton and Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which demanded that the Constitution be amended to grant the right to vote to all women. It also called for more lenient divorce laws and an end to sex discrimination in employment. The less radical Lucy Stone formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in the same year; AWSA hoped to win the suffrage for women by working on a state-by-state basis instead of seeking to amend the Constitution.[71] Four western states—Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and Idaho—did extend the right to vote to women in the late nineteenth century, but no other states did.

Women were also granted the right to vote on matters involving liquor licenses, in school board elections, and in municipal elections in several states. However, this was often done because of stereotyped beliefs that associated women with moral reform and concern for children, not as a result of a belief in women’s equality. Furthermore, voting in municipal elections was restricted to women who owned property.[72] In 1890, the two suffragist groups united to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). To call attention to their cause, members circulated petitions, lobbied politicians, and held parades in which hundreds of women and girls marched through the streets (Figure 13.12).

The more radical National Woman’s Party (NWP), led by Alice Paul, advocated the use of stronger tactics. The NWP held public protests and picketed outside the White House (Figure 13.13).[73] Demonstrators were often beaten and arrested, and suffragists were subjected to cruel treatment in jail. When some, like Paul, began hunger strikes to call attention to their cause, their jailers force-fed them, an incredibly painful and invasive experience for the women.[74] Finally, in 1920, the triumphant passage of the Nineteenth Amendment granted all women the right to vote.

Civil Rights and the Equal Rights Amendment

Just as the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments did not result in equality for African Americans, the Nineteenth Amendment did not end discrimination against women in education, employment, or other areas of life, which continued to be legal. Although women could vote, they very rarely ran for or held public office. Women continued to be underrepresented in the professions, and relatively few sought advanced degrees. Until the mid-twentieth century, the ideal in U.S. society was typically for women to marry, have children, and become housewives. Those who sought work for pay outside the home were routinely denied jobs because of their sex and, when they did find employment, were paid less than men. Women who wished to remain childless or limit the number of children they had in order to work or attend college found it difficult to do so. In some states it was illegal to sell contraceptive devices, and abortions were largely illegal and difficult for women to obtain.

A second women’s rights movement emerged in the 1960s to address these problems. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination in employment on the basis of sex as well as race, color, national origin, and religion. Nevertheless, women continued to be denied jobs because of their sex and were often sexually harassed at the workplace. In 1966, feminists who were angered by the lack of progress made by women and by the government’s lackluster enforcement of Title VII organized the National Organization for Women (NOW). NOW promoted workplace equality, including equal pay for women, and also called for the greater presence of women in public office, the professions, and graduate and professional degree programs.

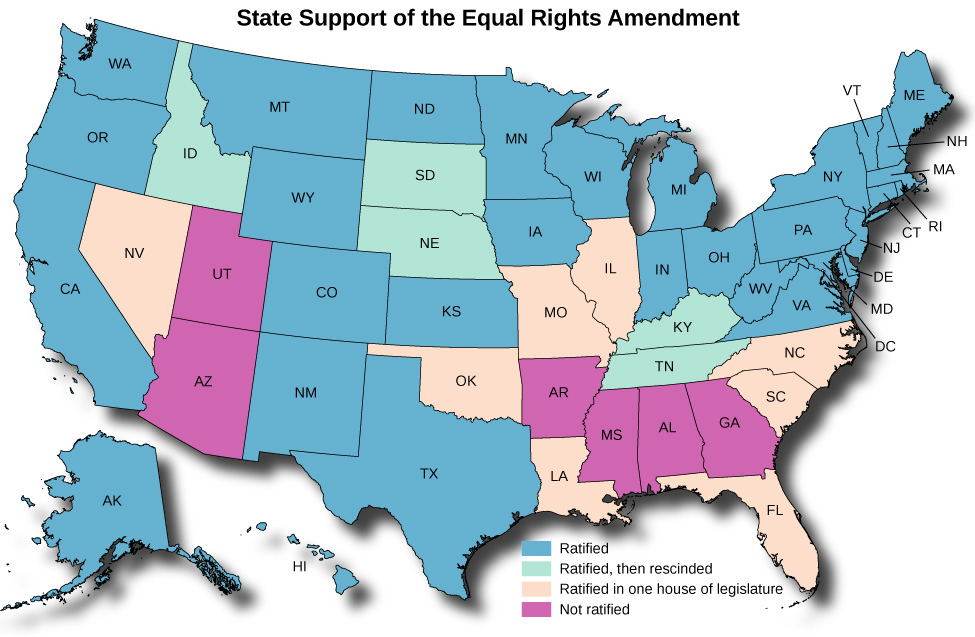

NOW also declared its support for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which mandated equal treatment for all regardless of sex. The ERA, written by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman, was first proposed to Congress, unsuccessfully, in 1923. It was introduced in every Congress thereafter but did not pass both the House and the Senate until 1972. The amendment was then sent to the states for ratification with a deadline of March 22, 1979. Although many states ratified the amendment in 1972 and 1973, the ERA still lacked sufficient support as the deadline drew near. Opponents, including both women and men, argued that passage would subject women to military conscription and deny them alimony and custody of their children should they divorce.[75] In 1978, Congress voted to extend the deadline for ratification to June 30, 1982. Even with the extension, however, the amendment failed to receive the support of the required thirty-eight states; by the time the deadline arrived, it had been ratified by only thirty-five, some of those had rescinded their ratifications, and no new state had ratified the ERA during the extension period (Figure 13.14). In 2020, Virginia became the thirty-eighth state to ratify, though well after the deadline. That led the U.S. House of Representatives to consider and pass legislation to remove the original deadlines. However, the Senate did not take up the legislation. In 2021, Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD) introduced a new joint resolution to remove the deadline. That resolution has yet to be taken up by the Senate.[76]

Although the ERA failed to be ratified, Title IX of the United States Education Amendments of 1972 passed into law as a federal statute (not as an amendment, as the ERA was meant to be). Title IX applies to all educational institutions that receive federal aid and prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in academic programs, dormitory space, health-care access, and school activities including sports. Thus, if a school receives federal aid, it cannot spend more funds on programs for men than on programs for women.

Continuing Challenges for Women

There is no doubt that women have made great progress since the Seneca Falls Convention. Today, more women than men attend college, and they are more likely than men to graduate.[77] Women are represented in all the professions, and approximately half of all law and medical school students are women.[78] Women have held Cabinet positions and have been elected to Congress. They have run for president and vice president, and three female justices currently serve on the Supreme Court. Women are also represented in all branches of the military and can serve in combat. As a result of the 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, women now have legal access to abortion.[79]

While women’s rights have progressed well beyond where they were in the 1800s, questions of equity continue. In 2021, the massive disparities between the facilities and housing for men and women in their respective NCAA national tournaments became front page news.[80] Also in the news recently were the disparities in pay and resources for the U.S. Men’s and Women’s National Soccer teams. Again, women received much less in terms of resources than men, despite (in this case) being the more successful international team and World Cup champions.[81] In the business world, women are still underrepresented in some jobs and are less likely to hold executive positions than are men.

Many believe the glass ceiling, an invisible barrier caused by discrimination, prevents women from rising to the highest levels of American organizations, including corporations, governments, academic institutions, and religious groups. Women earn less money than men for the same work. As of 2014, fully employed women earned seventy-nine cents for every dollar earned by a fully employed man.[82] This problem may be compounded by other factors, as women from under-represented groups are even more discriminated against than other women.[83] Women are also more likely to be single parents than are men.[84] As a result, more women live below the poverty line than do men, and, as of 2012, households headed by single women are twice as likely to live below the poverty line than those headed by single men.[85] Women remain underrepresented in elective offices. As of June 2021, women held only about 27 percent of seats in Congress and only about 31 percent of seats in state legislatures.[86]

Women remain subject to sexual harassment in the workplace and are more likely than men to be the victims of domestic violence. Approximately one-third of all women have experienced domestic violence; one in five women is assaulted during her college years.[87]

Many in the United States continue to call for a ban on abortion, and states have attempted to restrict women’s access to the procedure. For example, many states have required abortion clinics to meet the same standards set for hospitals, such as corridor size and parking lot capacity, despite lack of evidence regarding the benefits of such standards. Abortion clinics, which are smaller than hospitals, often cannot meet such standards. Other restrictions include mandated counseling before the procedure and the need for minors to secure parental permission before obtaining abortion services.[88] Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016) cited the lack of evidence for the benefit of larger clinics and further disallowed two Texas laws that imposed special requirements on doctors in order to perform abortions.[89] Furthermore, the federal government will not pay for abortions for low-income women except in cases of rape or incest or in situations in which carrying the fetus to term would endanger the life of the mother.[90]

To address these issues, many have called for additional protections for women. These include laws mandating equal pay for equal work. According to the doctrine of comparable worth, people should be compensated equally for work requiring comparable skills, responsibilities, and effort. Thus, even though women are underrepresented in certain fields, they should receive the same wages as men if performing jobs requiring the same level of accountability, knowledge, skills, and/or working conditions, even though the specific job may be different.

For example, garbage collectors are predominantly male. The chief job requirements are the ability to drive a sanitation truck and to lift heavy bins and toss their contents into the back of truck. The average wage for a garbage collector is $15.34 an hour.[91] Most people employed as daycare workers are female, and the average pay is $9.12 an hour.[92] However, the work arguably requires more skills and is a more responsible position. Daycare workers must be able to feed, clean, and dress small children; prepare meals for them; entertain them; give them medicine if required; and teach them basic skills. They must be educated in first aid and assume responsibility for the children’s safety. In terms of the skills and physical activity required and the associated level of responsibility of the job, daycare workers should be paid at least as much as garbage collectors and perhaps more. Women’s rights advocates also call for stricter enforcement of laws prohibiting sexual harassment, and for harsher punishment, such as mandatory arrest, for perpetrators of domestic violence.

INSIDER PERSPECTIVE

Harry Burn and the Tennessee General Assembly

In 1918, the proposed Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, extending the right to vote to all adult female citizens of the United States, was passed by both houses of Congress and sent to the states for ratification. Thirty-six votes were needed. Throughout 1918 and 1919, the Amendment dragged through legislature after legislature as pro- and anti-suffrage advocates made their arguments. By the summer of 1920, only one more state had to ratify it before it became law. The Amendment passed through Tennessee’s state Senate and went to its House of Representatives. Arguments were bitter and intense. Pro-suffrage advocates argued that the amendment would reward women for their service to the nation during World War I and that women’s supposedly greater morality would help to clean up politics. Those opposed claimed women would be degraded by entrance into the political arena and that their interests were already represented by their male relatives. On August 18, the amendment was brought for a vote before the House. The vote was closely divided, and it seemed unlikely it would pass. But as a young anti-suffrage representative waited for his vote to be counted, he remembered a note he had received from his mother that day. In it, she urged him, “Hurrah and vote for suffrage!” At the last minute, Harry Burn abruptly changed his ballot. The amendment passed the House by one vote, and eight days later, the Nineteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution.

How are women perceived in politics today compared to the 1910s? What were the competing arguments for Harry Burn’s vote?

LINK TO LEARNING

The website for the Women’s National History Project contains a variety of resources for learning more about the women’s rights movement and women’s history. It features a history of the women’s movement, a “This Day in Women’s History” page, and quizzes to test your knowledge.

13.5 Civil Rights for Indigenous Groups: Native Americans, Alaskans, and Hawaiians

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Outline the history of discrimination against Native Americans

- Describe the expansion of Native American civil rights from 1960 to 1990

- Discuss the persistence of problems Native Americans face today

Native Americans have long suffered the effects of segregation and discrimination imposed by the U.S. government and the larger White society. Ironically, Native Americans were not granted the full rights and protections of U.S. citizenship until long after African Americans and women were, with many having to wait until the Nationality Act of 1940 to become citizens.[93] This was long after the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, which granted citizenship to African Americans but not, the Supreme Court decided in Elk v. Wilkins (1884), to Native Americans.[94] White women had been citizens of the United States since its very beginning even though they were not granted the full rights of citizenship. Furthermore, Native Americans are the only group of Americans who were forcibly removed en masse from the lands on which they and their ancestors had lived so that others could claim this land and its resources. This issue remains relevant today as can be seen in the recent protests of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which have led to intense confrontations between those in charge of the pipeline and Native Americans.

LINK TO LEARNING

*Watch this video to learn more about discrimination in the United States.

Native Americans Lose Their Land and Their Rights

As White settlement spread westward over the course of the nineteenth century, Indian tribes were forced to move from their homelands. Although the federal government signed numerous treaties guaranteeing Indians the right to live in the places where they had traditionally farmed, hunted, or fished, land-hungry White settlers routinely violated these agreements and the federal government did little to enforce them.[97]

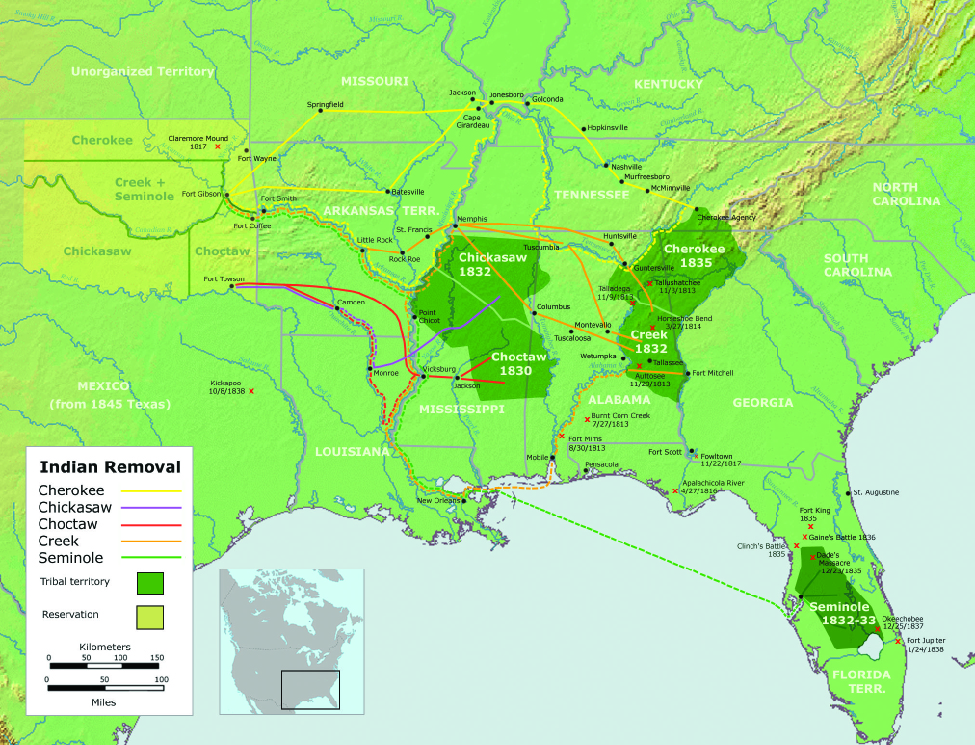

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which forced Native Americans to move west of the Mississippi River.[98] Not all tribes were willing to leave their land, however. The Cherokee in particular resisted, and in the 1820s, the state of Georgia tried numerous tactics to force them from their territory. Efforts intensified in 1829 after gold was discovered there. Wishing to remain where they were, the tribe sued the state of Georgia.[99] In 1831, the Supreme Court decided in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia that Indian tribes were not sovereign nations, but also that tribes were entitled to their ancestral lands and could not be forced to move from them.[100]

The next year, in Worcester v. Georgia, the Court ruled that non-Native Americans could not enter tribal lands without the tribe’s permission. White Georgians, however, refused to abide by the Court’s decision, and President Andrew Jackson, a former Indian fighter, refused to enforce it.[101] Between 1831 and 1838, members of several southern tribes, including the Cherokees, were forced by the U.S. Army to move west along routes shown in Figure 13.15. The forced removal of the Cherokees to Oklahoma Territory, which had been set aside for settlement by displaced tribes and designated Indian Territory, resulted in the death of one-quarter of the tribe’s population.[102] The Cherokees remember this journey as the Trail of Tears.

By the time of the Civil War, most Indian tribes had been relocated west of the Mississippi. However, once large numbers of White Americans and European immigrants had also moved west after the Civil War, Native Americans once again found themselves displaced. They were confined to reservations, which are federal lands set aside for their use where non-Indians could not settle. Reservation land was usually poor, however, and attempts to farm or raise livestock, not traditional occupations for most western tribes anyway, often ended in failure. Unable to feed themselves, the tribes became dependent on the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in Washington, DC, for support. Protestant missionaries were allowed to “adopt” various tribes, to convert them to Christianity and thus speed their assimilation. In an effort to hasten this process, Indian children were taken from their parents and sent to boarding schools, many of them run by churches, where they were forced to speak English and abandon their traditional cultures.[103]

In 1887, the Dawes Severalty Act, another effort to assimilate Indians to White society, divided reservation lands into individual allotments. Native Americans who accepted these allotments and agreed to sever tribal ties were also given U.S. citizenship. All lands remaining after the division of reservations into allotments were offered for sale by the federal government to White farmers and ranchers. As a result, Indians swiftly lost control of reservation land.[104] In 1898, the Curtis Act dealt the final blow to Indian sovereignty by abolishing all tribal governments.[105]

The Fight for Native American Rights

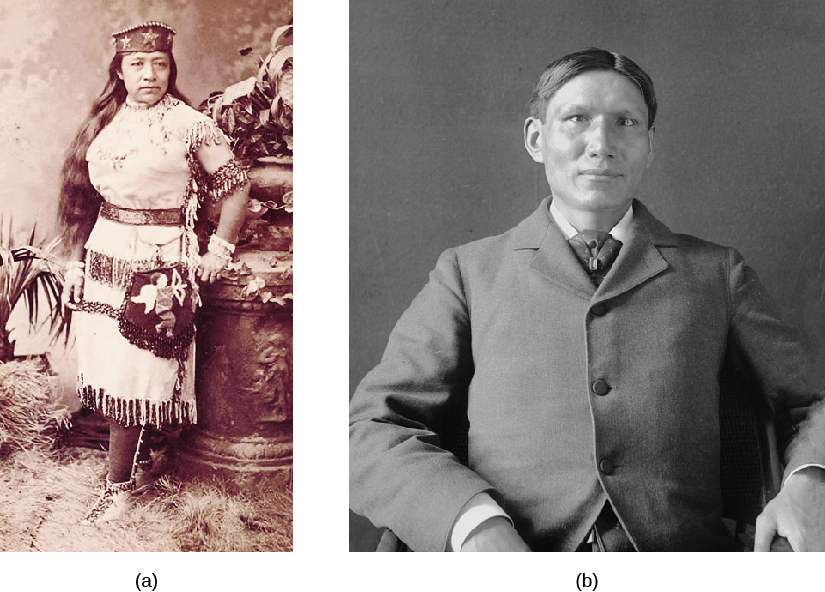

As Indians were removed from their tribal lands and increasingly saw their traditional cultures being destroyed over the course of the nineteenth century, a movement to protect their rights began to grow. Sarah Winnemucca (Figure 13.16), member of the Paiute tribe, lectured throughout the east in the 1880s in order to acquaint White audiences with the injustices suffered by the western tribes.[106] Lakota physician Charles Eastman (Figure 13.16) also worked for Native American rights. In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act granted citizenship to all Native Americans born after its passage. Native Americans born before the act took effect, who had not already become citizens as a result of the Dawes Severalty Act or service in the army in World War I, had to wait until the Nationality Act of 1940 to become citizens. In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act, which ended the division of reservation land into allotments. It returned to Native American tribes the right to institute self-government on their reservations, write constitutions, and manage their remaining lands and resources. It also provided funds for Native Americans to start their own businesses and attain a college education.[107]

Despite the Indian Reorganization Act, conditions on the reservations did not improve dramatically. Most tribes remained impoverished, and many Native Americans, despite the fact that they were now U.S. citizens, were denied the right to vote by the states in which they lived. States justified this violation of the Fifteenth Amendment by claiming that Native Americans might be U.S. citizens but were not state residents because they lived on reservations. Other states denied Native Americans voting rights if they did not pay taxes.[108] Despite states’ actions, the federal government continued to uphold the rights of tribes to govern themselves. Federal concern for tribal sovereignty was part of an effort on the government’s part to end its control of, and obligations to, Indian tribes.[109]

In the 1960s, a modern Native American civil rights movement, inspired by the African American civil rights movement, began to grow. In 1969, a group of Native American activists from various tribes, part of a new Pan-Indian movement, took control of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, which had once been the site of a federal prison. Attempting to strike a blow for Red Power, the power of Native Americans united by a Pan-Indian identity and demanding federal recognition of their rights, they maintained control of the island for more than a year and a half. They claimed the land as compensation for the federal government’s violation of numerous treaties and offered to pay for it with beads and trinkets. In January 1970, some of the occupiers began to leave the island. Some may have been disheartened by the accidental death of the daughter of one of the activists. In May 1970, all electricity and telephone service to the island was cut off by the federal government, and more of the occupiers began to leave. In June, the few people remaining on the island were removed by the government. Though the goals of the activists were not achieved, the occupation of Alcatraz had brought national attention to the concerns of Native American activists.[110]

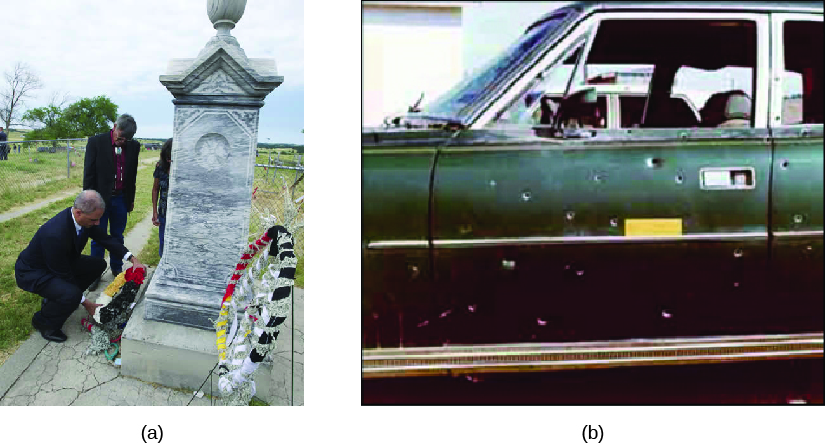

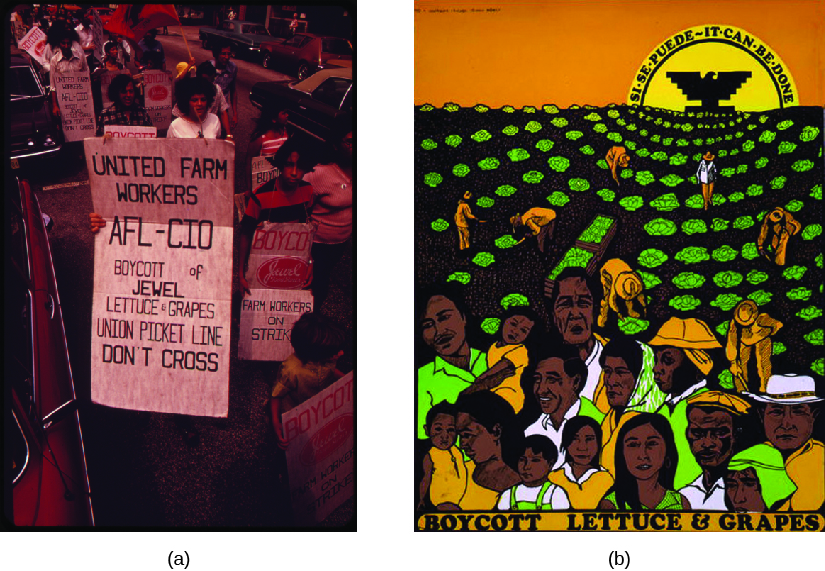

In 1973, members of the American Indian Movement (AIM), a more radical group than the occupiers of Alcatraz, temporarily took over the offices of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, DC. The following year, members of AIM and some two hundred Oglala Lakota supporters occupied the town of Wounded Knee on the Lakota tribe’s Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, the site of an 1890 massacre of Lakota men, women, and children by the U.S. Army (Figure 13.17). Many of the Oglala were protesting the actions of their half-White tribal chieftain, who they claimed had worked too closely with the BIA. The occupiers also wished to protest the failure of the Justice Department to investigate acts of White violence against Lakota tribal members outside the bounds of the reservation.

The occupation led to a confrontation between the Native American protestors and the FBI and U.S. Marshals. Violence erupted; two Native American activists were killed, and a marshal was shot (Figure 13.17). After the second death, the Lakota called for an end to the occupation and negotiations began with the federal government. Two of AIM’s leaders, Russell Means and Dennis Banks, were arrested, but the case against them was later dismissed.[111] Violence continued on the Pine Ridge Reservation for several years after the siege; the reservation had the highest per capita murder rate in the United States. Two FBI agents were among those who were killed. The Oglala blamed the continuing violence on the federal government.[112]

LINK TO LEARNING

The official website of the American Indian Movement provides information about ongoing issues in Native American communities in both North and South America.